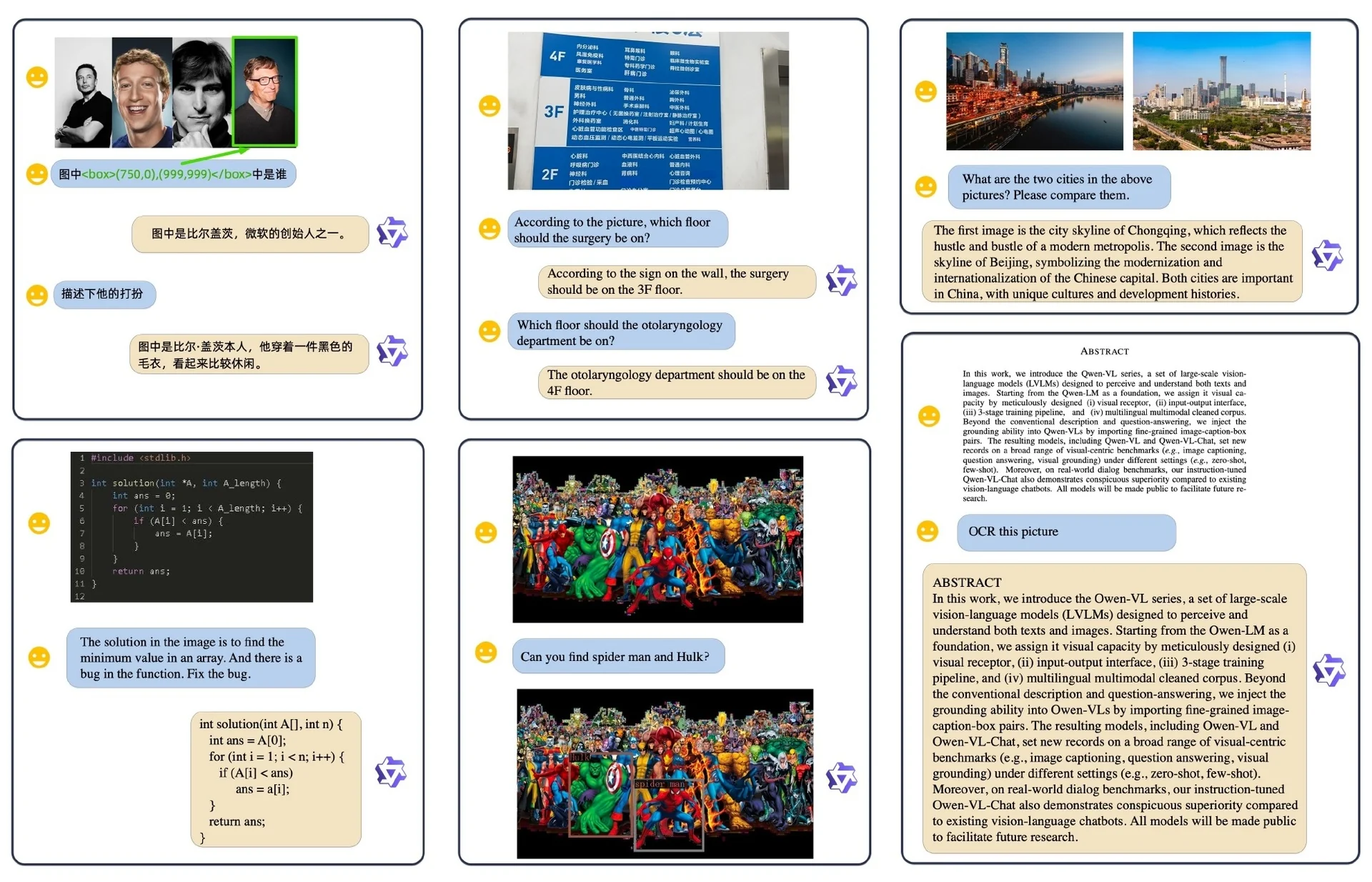

Lecture 24: Videos (Video Understanding)

24.1 Introduction to Video Understanding

Up to this point, our discussion has focused mainly on images, typically represented as 3D tensors of shape \(C \times H \times W\), where \(C\) denotes the number of channels (often three for RGB). In this chapter we generalize from static images to videos, which can be viewed as sequences of images indexed by time. A video is therefore represented by a 4D tensor of shape: \begin {equation} \label {eq:chapter24_video_tensor} \mathbf {V} \in \mathbb {R}^{T \times C \times H \times W}, \end {equation} where \(T\) denotes the temporal dimension, corresponding to the number of frames in the sequence.

This extension introduces a fundamental challenge: while image analysis largely emphasizes spatial patterns, video understanding requires us to jointly reason about spatial and temporal structures. Tasks defined over videos range widely, from video classification and temporal action localization to video captioning and generation. In this lecture and chapter we focus on video understanding, that is, building models that interpret the content of a video clip to predict semantic properties such as actions, interactions, or events.

24.1.1 From Images to Videos

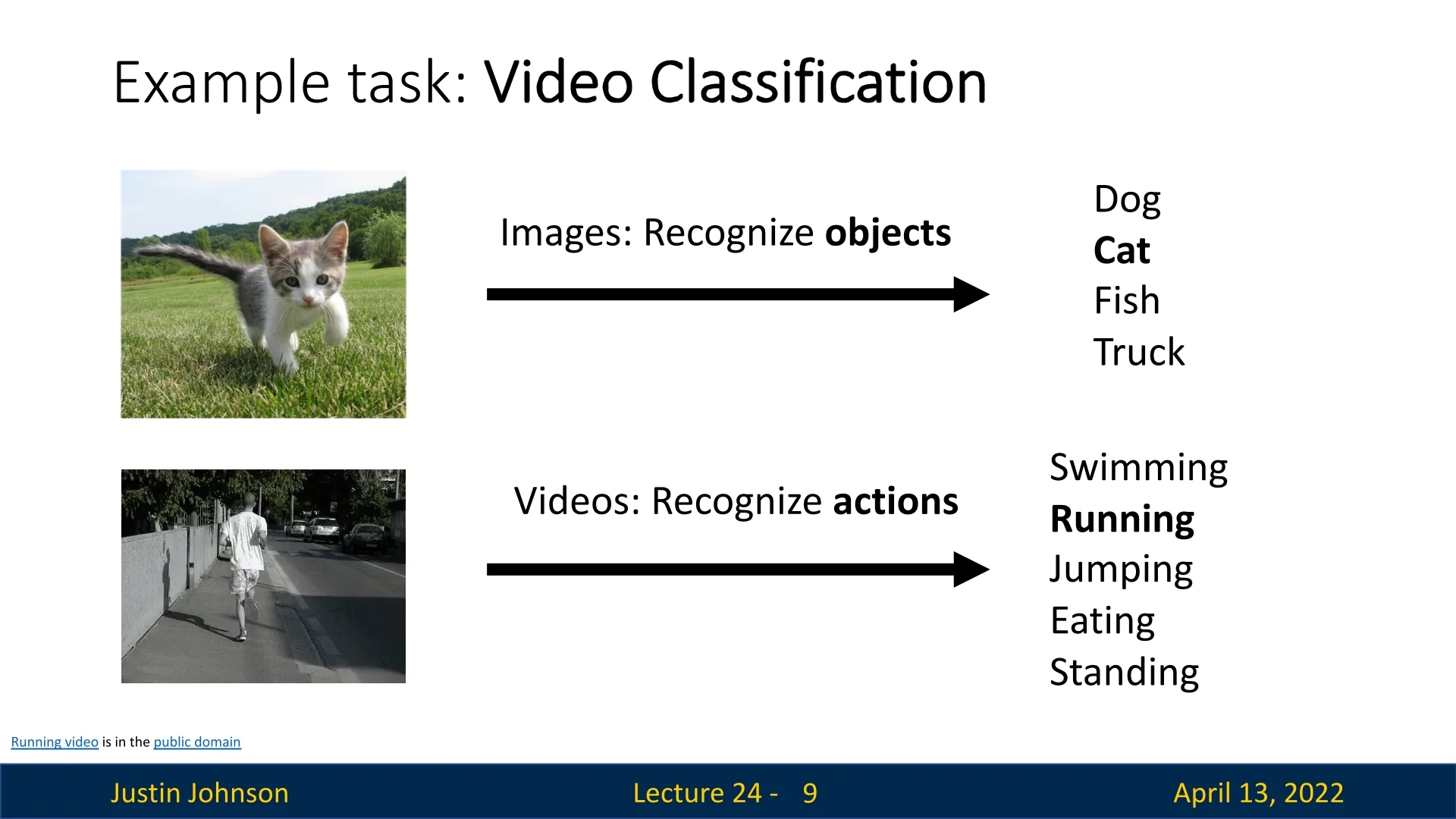

In image classification, the objective is typically to detect the presence of objects (e.g., predicting that an image contains a cat). In contrast, video classification aims to recognize actions. For example, given a short clip of a person, the model should distinguish whether the individual is running, walking, jumping, or standing. This shift from nouns (objects) to verbs (actions) reflects the additional temporal complexity inherent in videos.

24.1.2 Challenges of Video Data and Clip-Based Training

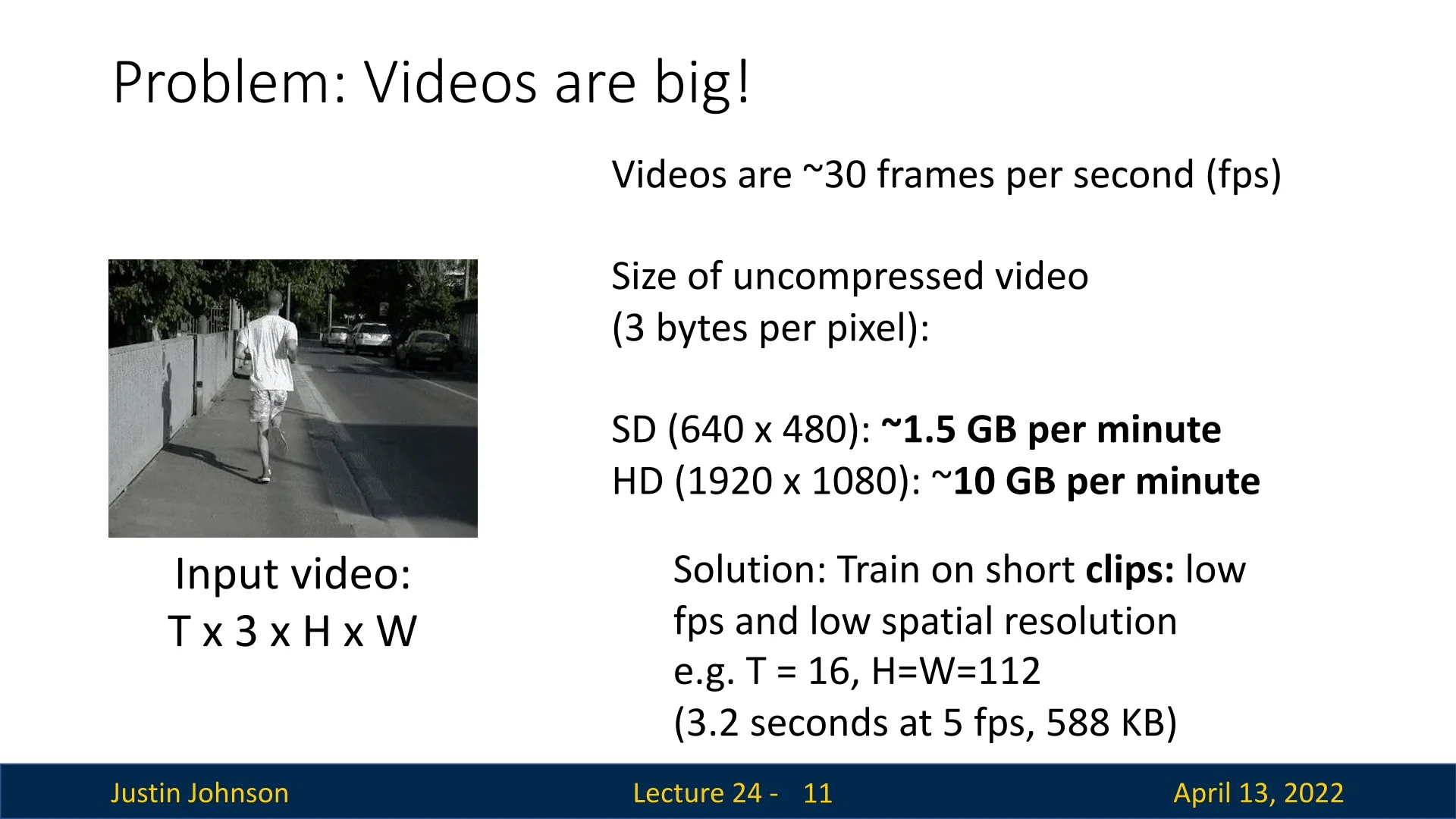

Videos present substantial computational burdens compared to images. A standard video stream is recorded at approximately 30 frames per second, with each frame containing hundreds of thousands or millions of pixels. For example, storing an uncompressed video requires approximately:

- \(\sim \)1.5 GB per minute for standard definition (640 \(\times \) 480),

- \(\sim \)10 GB per minute for high definition (1920 \(\times \) 1080).

This scale makes it infeasible to directly train on raw, full-length videos.

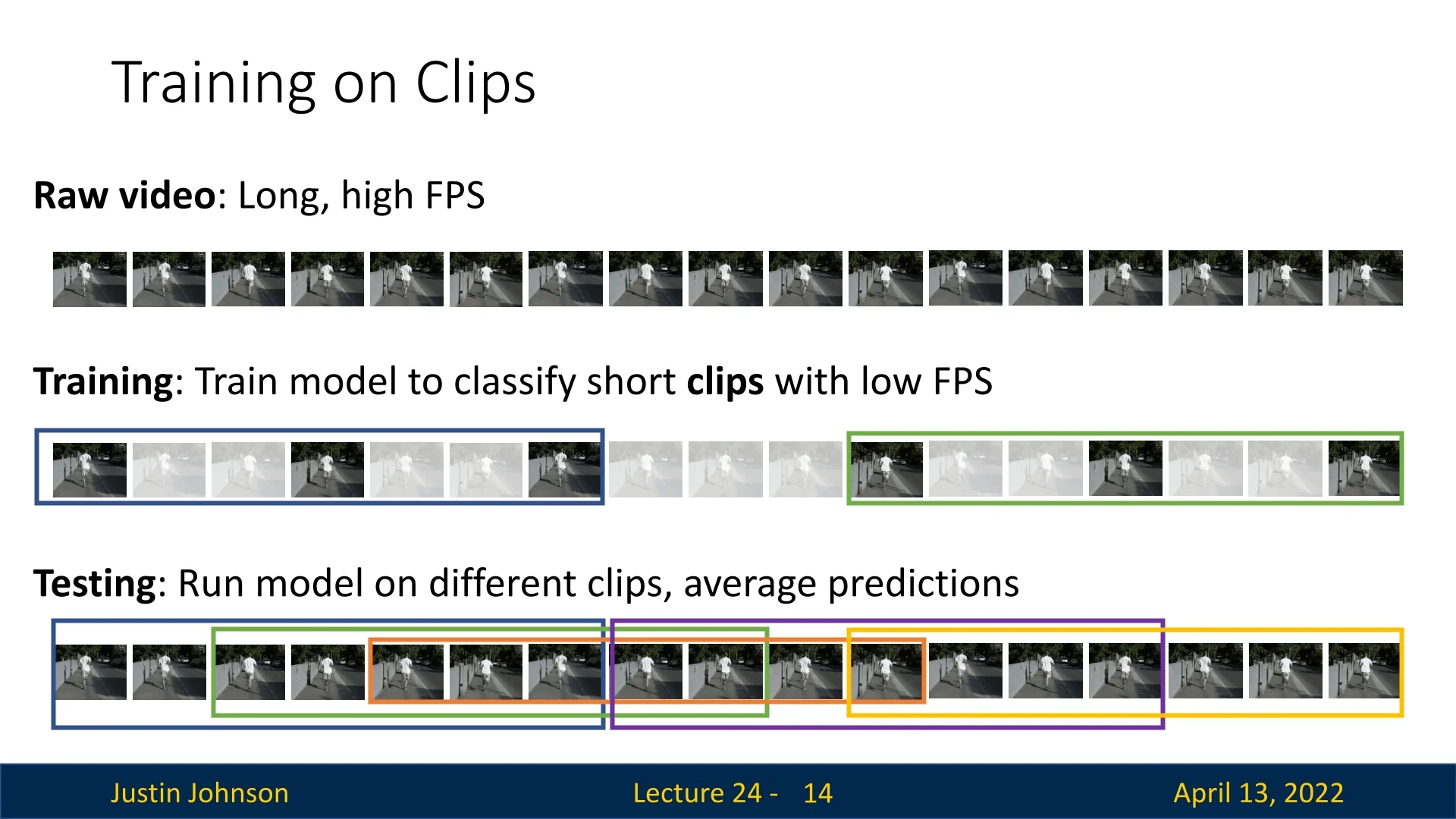

The standard solution is to train on short clips rather than entire videos. A raw sequence of length \(T_\mbox{raw}\) is divided into windows of \(T\) consecutive frames, often subsampled in time (e.g., taking every \(k\)th frame) to reduce the effective frame rate. Clips are also downsampled spatially (e.g., \(112 \times 112\) pixels). During training, models are supervised on these short clips.

At test time, multiple clips are sampled from different temporal regions of the video. The model processes each subclip independently, and the results are aggregated—typically via averaging—to produce a robust video-level prediction.

24.2 Video Classification as a Canonical Task

Video classification serves as a canonical entry point into video understanding. The task is defined as mapping an input clip \(\mathbf {V} \in \mathbb {R}^{T \times C \times H \times W}\) to a label \(y \in \{1,\dots ,K\}\) from a fixed action vocabulary of size \(K\). Formally, we seek to learn a function \begin {equation} \label {eq:chapter24_video_classification} f_\theta : \mathbb {R}^{T \times C \times H \times W} \to \{1,\dots ,K\}, \end {equation} where \(\theta \) denotes the parameters of the model. As in image classification, the system is typically trained with cross-entropy loss. However, the network architecture must incorporate temporal reasoning, either explicitly or implicitly, in order to succeed.

This formulation establishes video classification as a foundation for more advanced video understanding tasks, such as temporal action localization (detecting when an action occurs within an untrimmed video) and spatio-temporal action detection (localizing actions in both space and time). In the following parts, we progressively build models to handle the spatio-temporal complexity of videos, beginning with simple baselines and gradually extending to sophisticated architectures.

24.2.1 Single-Frame Baseline

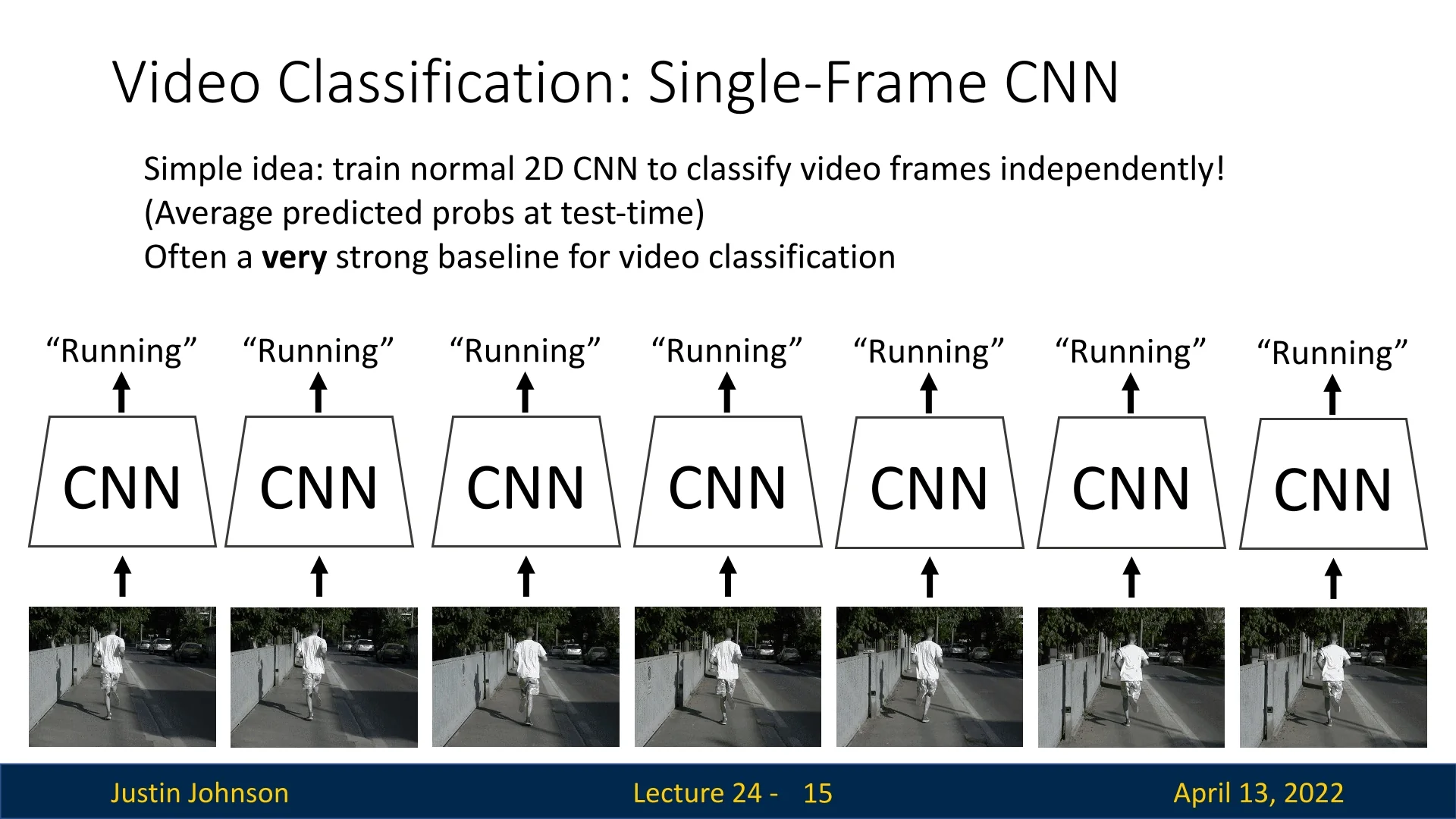

An unexpectedly strong baseline for video classification is to ignore temporal information entirely. In this approach, each frame is classified independently using a standard 2D CNN trained on individual RGB frames with the video-level label. At test time, predictions across frames are averaged to obtain the final decision. While simple, this baseline often achieves competitive accuracy and should always be attempted first in practice.

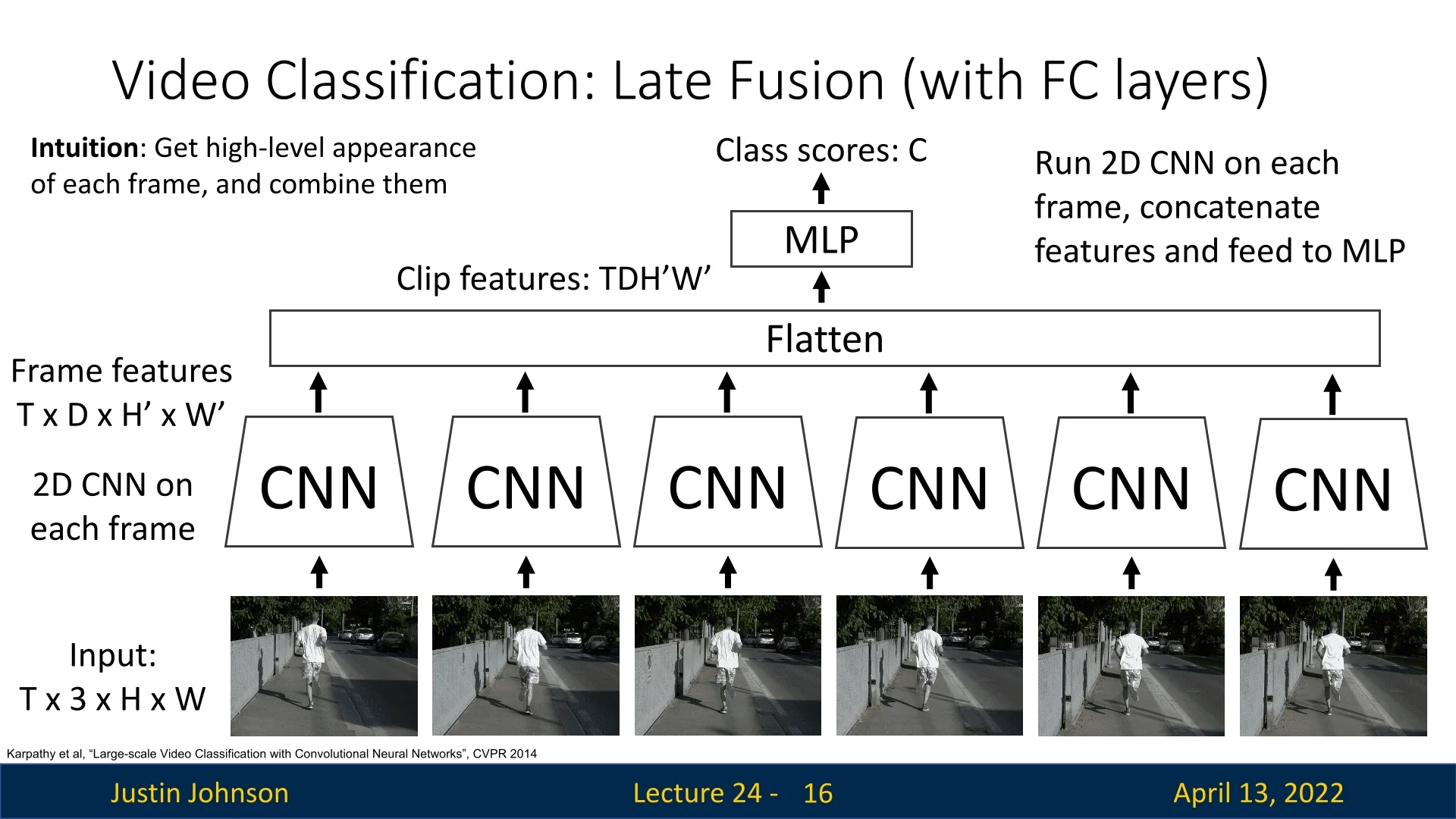

24.2.2 Late Fusion

To incorporate temporal reasoning, a natural extension is late fusion. Here, each frame is first processed independently by a 2D CNN to produce feature maps of shape \(D \times H' \times W'\). The sequence of features across \(T\) frames is then concatenated into a tensor of shape \(T \times D \times H' \times W'\). This can be flattened into a single feature vector of dimension \(TDH'W'\), followed by fully connected layers and a softmax classifier: \begin {equation} \label {eq:chapter24_late_fusion} \hat {y} = \mbox{Softmax}\big ( \mbox{MLP}(\mbox{Flatten}(\{f_1,\dots ,f_T\})) \big ), \end {equation} where \(f_t\) denotes the per-frame CNN features.

The intuition is that we first capture high-level appearance in each frame and then combine them at the classification stage.

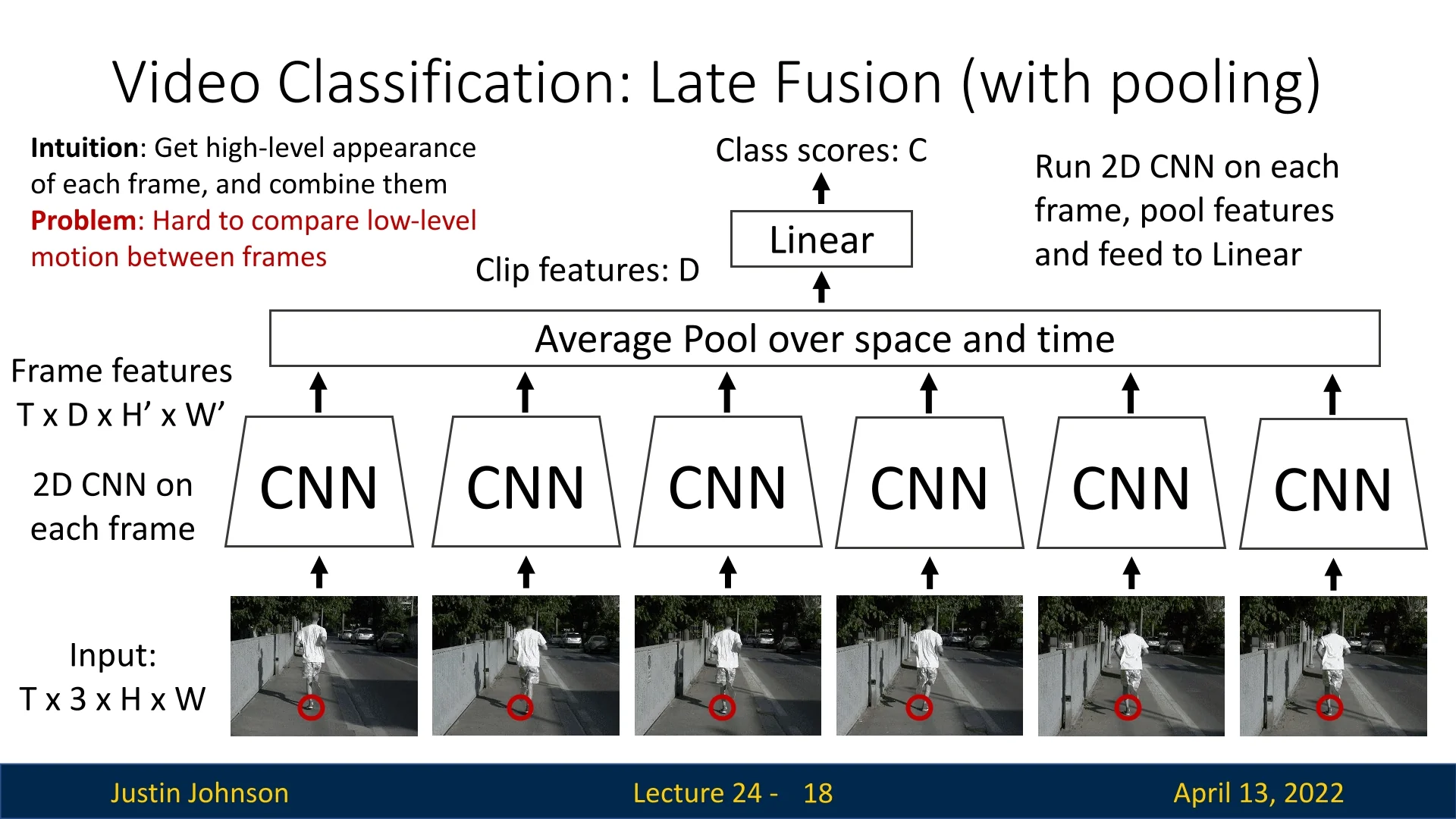

A more parameter-efficient variant replaces the flatten–FC stage with global average pooling (GAP) over both spatial and temporal dimensions, yielding a compact \(D\)-dimensional vector before the classifier. While effective at reducing overfitting, late fusion methods have a key limitation: they struggle to capture fine-grained motion signals between consecutive frames, since temporal information is collapsed only at a late stage.

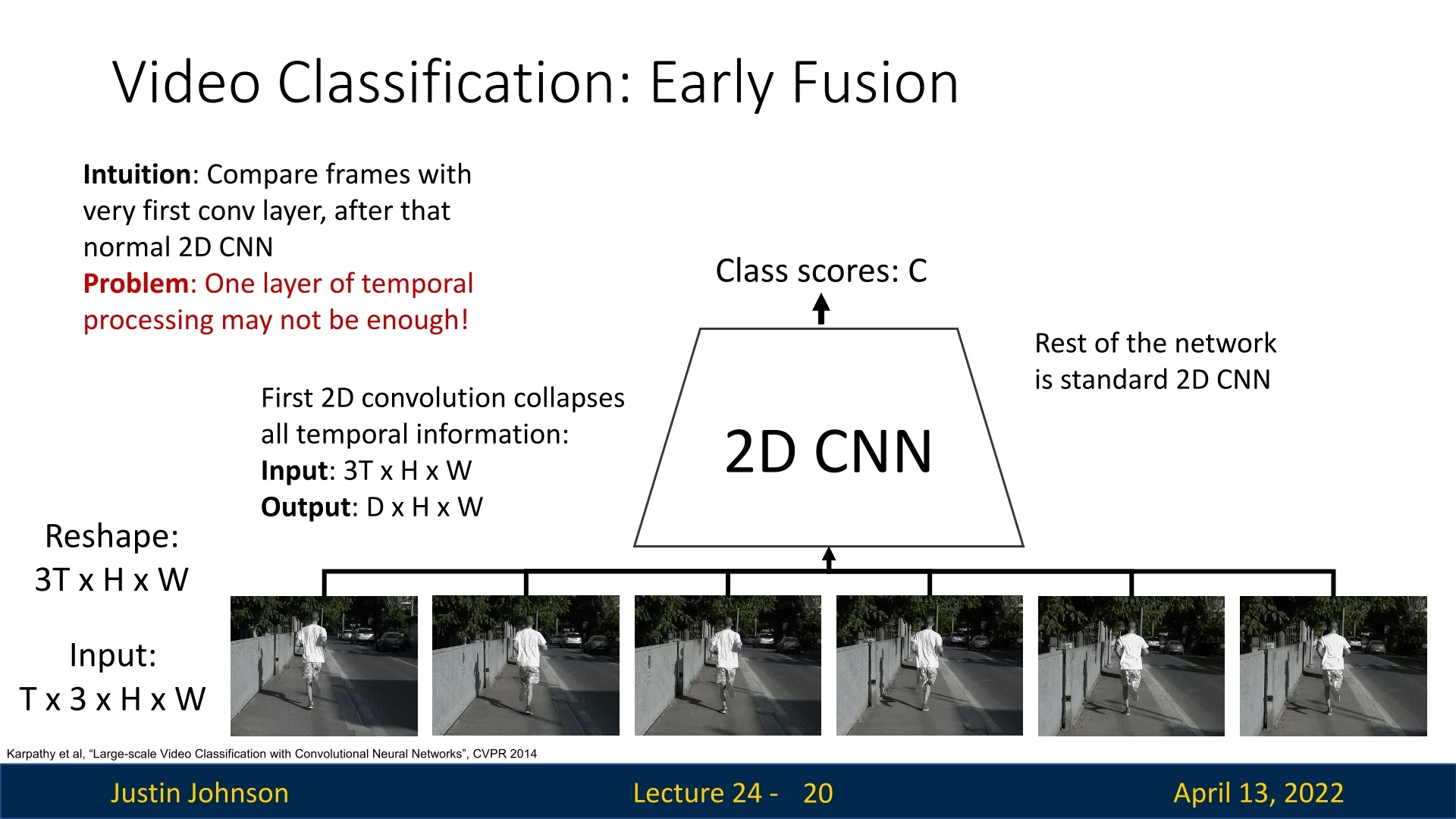

24.2.3 Early Fusion

To better model small/fine-grained temporal dynamics, we can adopt early fusion. Here, the temporal dimension is reshaped into the channel dimension: the input clip \(\mathbb {R}^{T \times 3 \times H \times W}\) is reformatted into \(\mathbb {R}^{3T \times H \times W}\). A 2D CNN is then applied, treating time-stacked frames as an enlarged channel input. This allows the first convolutional layer to directly compare pixel intensities across adjacent frames, thereby capturing short-term motion.

While this mitigates late fusion’s inability to capture motion, the temporal dimension is collapsed after the first convolution. This one-shot fusion can be overly aggressive, discarding longer-range temporal information, and thus harm classification results.

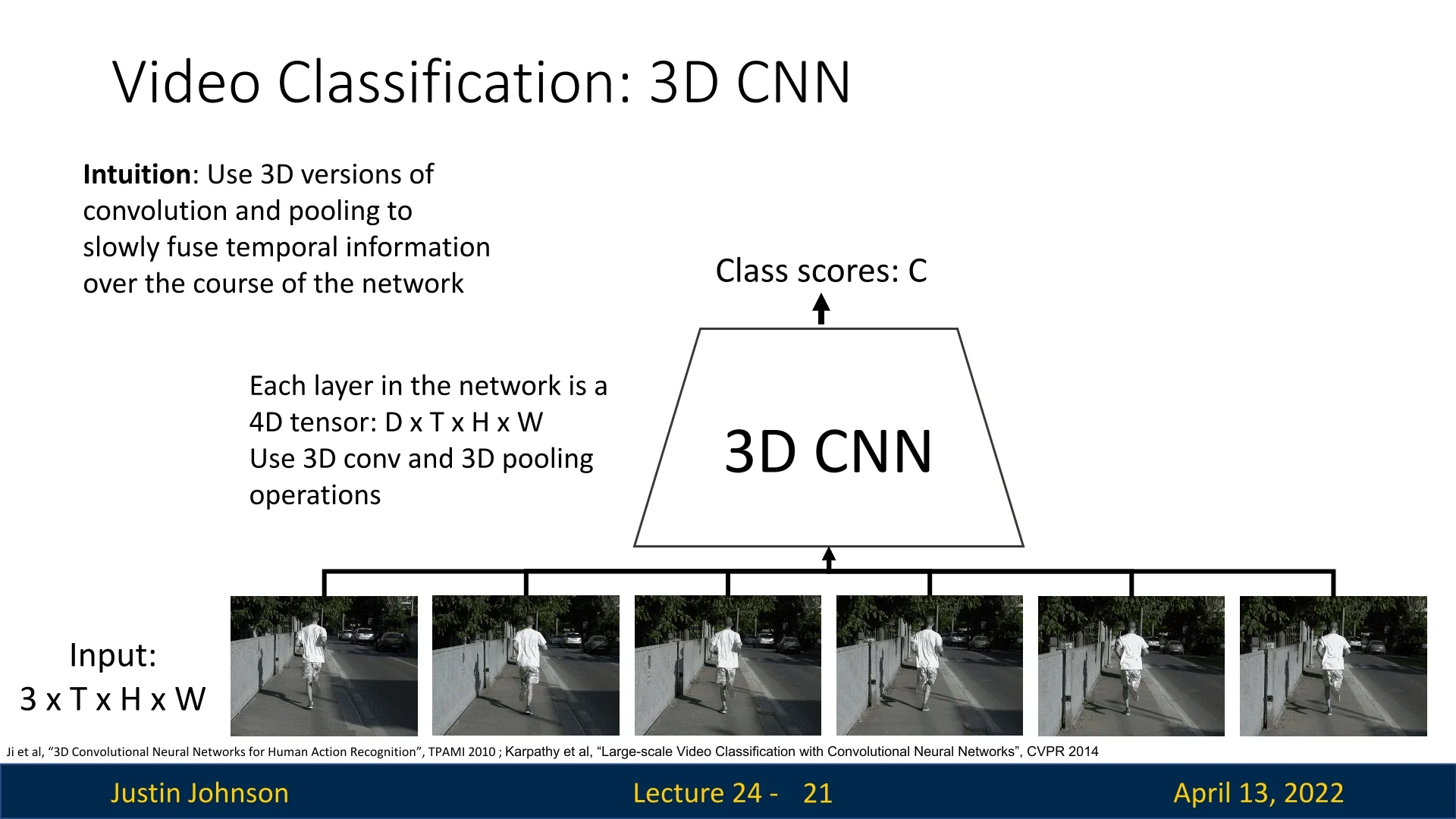

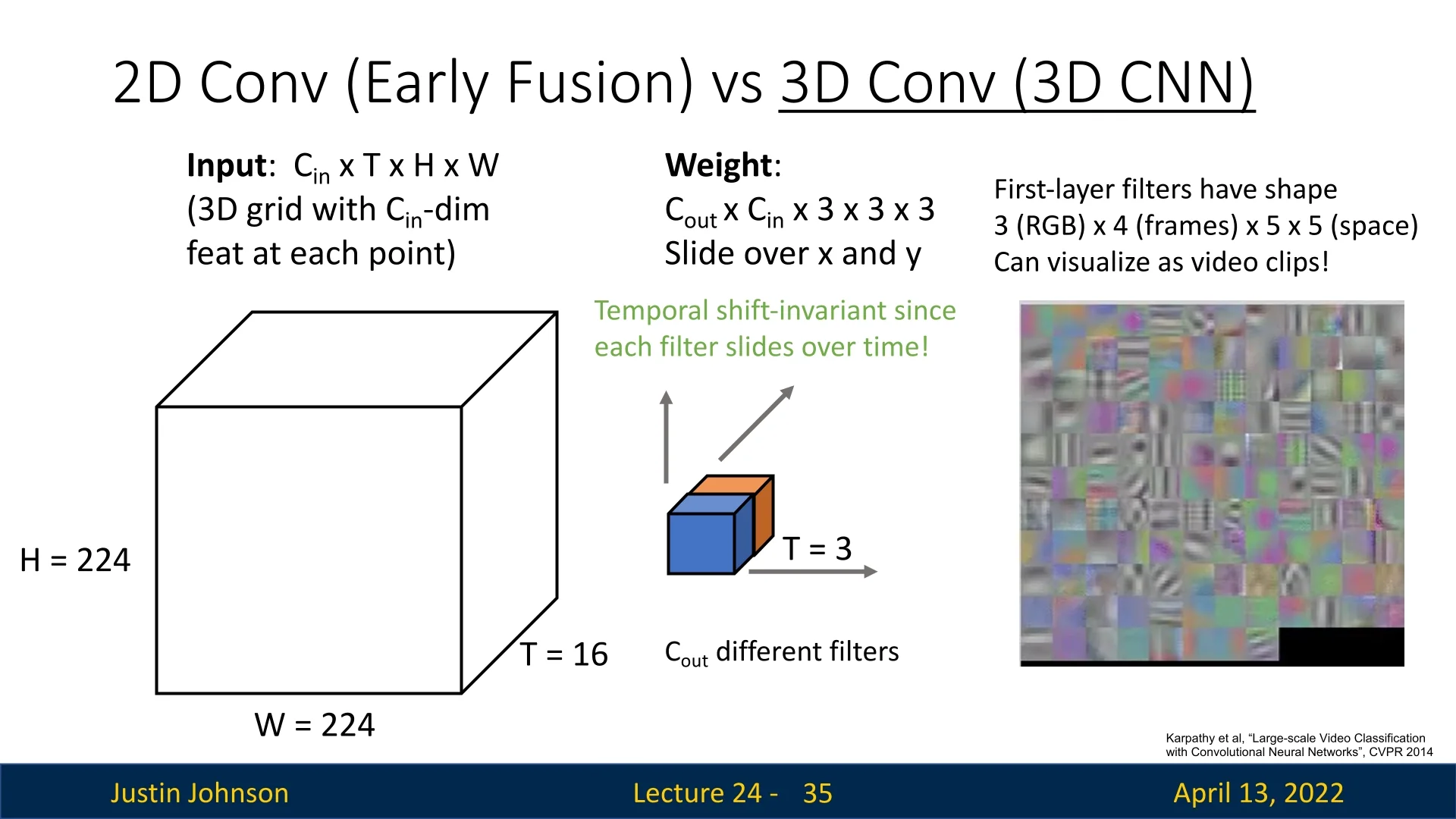

24.2.4 3D CNNs: Slow Fusion

A natural extension of 2D convolution to video is to treat time as an additional dimension and apply 3D convolutions. In this design, filters have shape \(K_t \times K_h \times K_w\), spanning the temporal axis as well as the spatial axes. Activations remain four-dimensional (\(D \times T \times H \times W\)), where \(T\) denotes temporal extent. By stacking such layers, temporal information is fused progressively across depth—an approach known as slow fusion.

This architecture enables hierarchical learning of spatiotemporal features: early layers may detect short-term motion edges, while deeper layers aggregate evidence for longer-term dynamics. The formulation was pioneered in early works such as [263, 276].

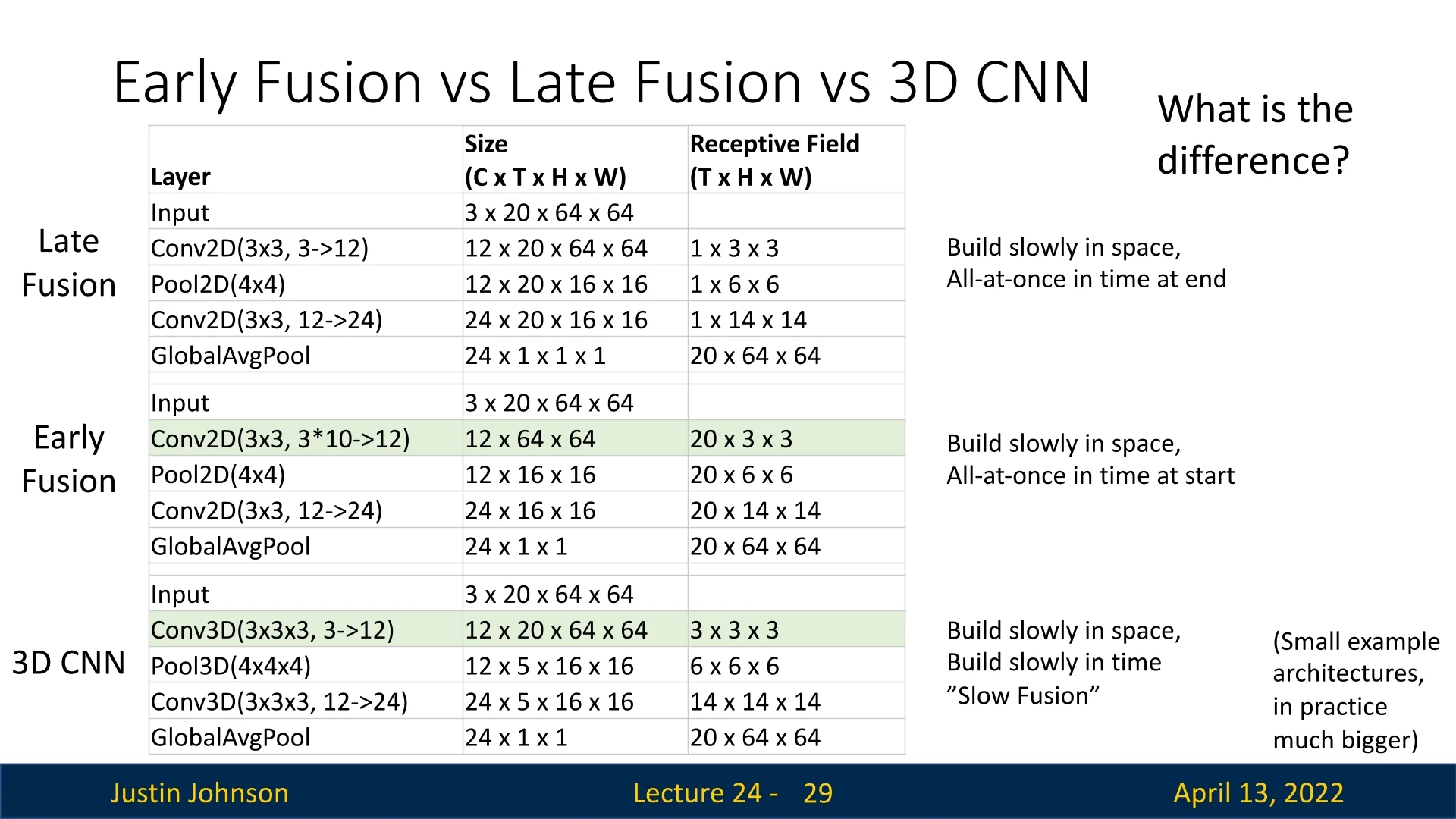

Comparison with fusion alternatives. To place 3D CNNs in context, it is helpful to compare with early and late fusion strategies. In early fusion, temporal information is aggregated at the input by stacking frames as channels, while spatial receptive fields grow across depth. In late fusion, each frame is processed independently by 2D CNNs, and temporal integration occurs only at the final stage. By contrast, 3D CNNs (slow fusion) expand both spatial and temporal receptive fields gradually, balancing spatial and temporal modeling capacity.

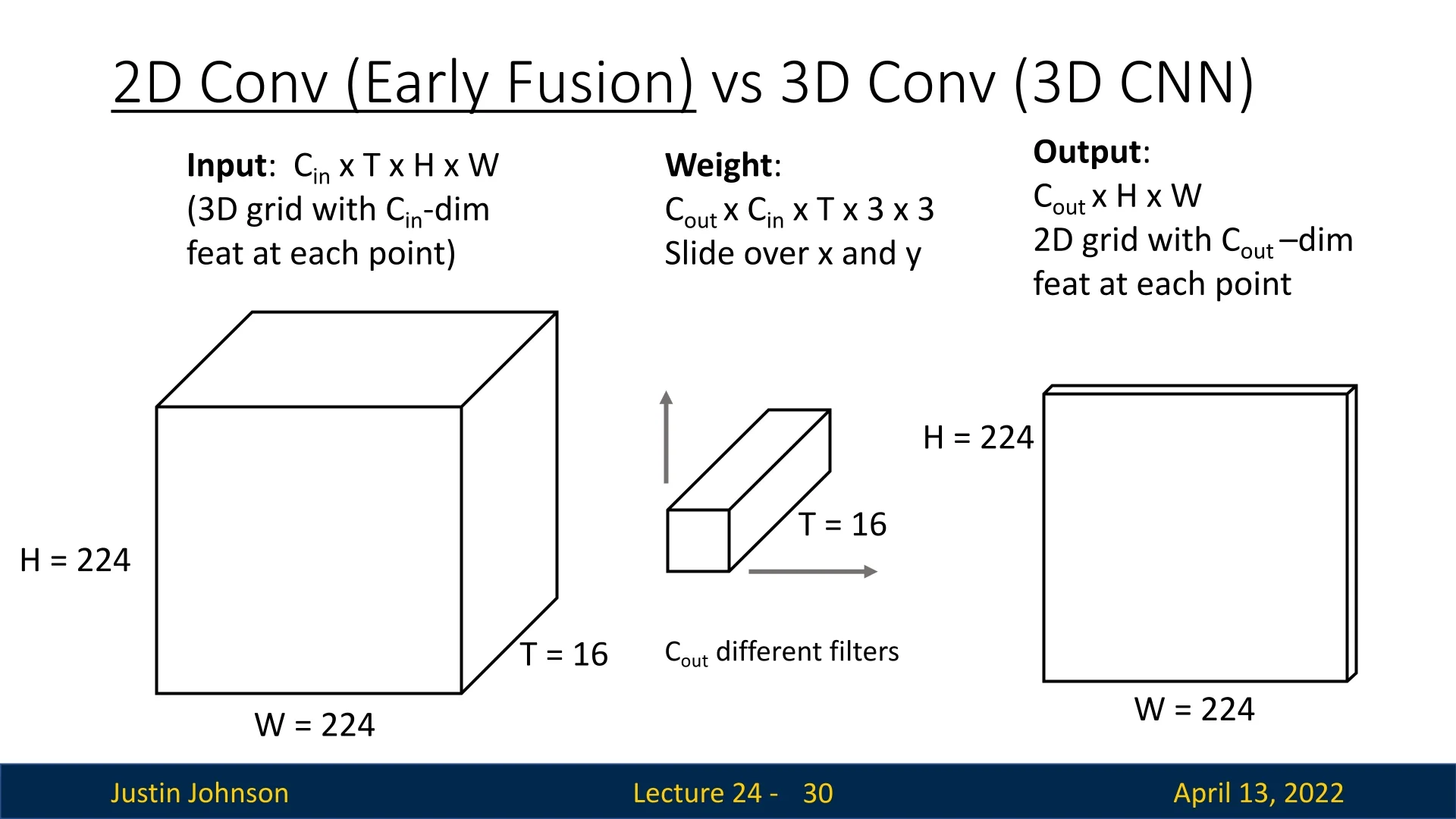

24.2.5 2D vs 3D Convolutions

To better understand the distinction between early fusion with 2D convolutions and true 3D convolutions, it is useful to analyze how their filters operate over time:

-

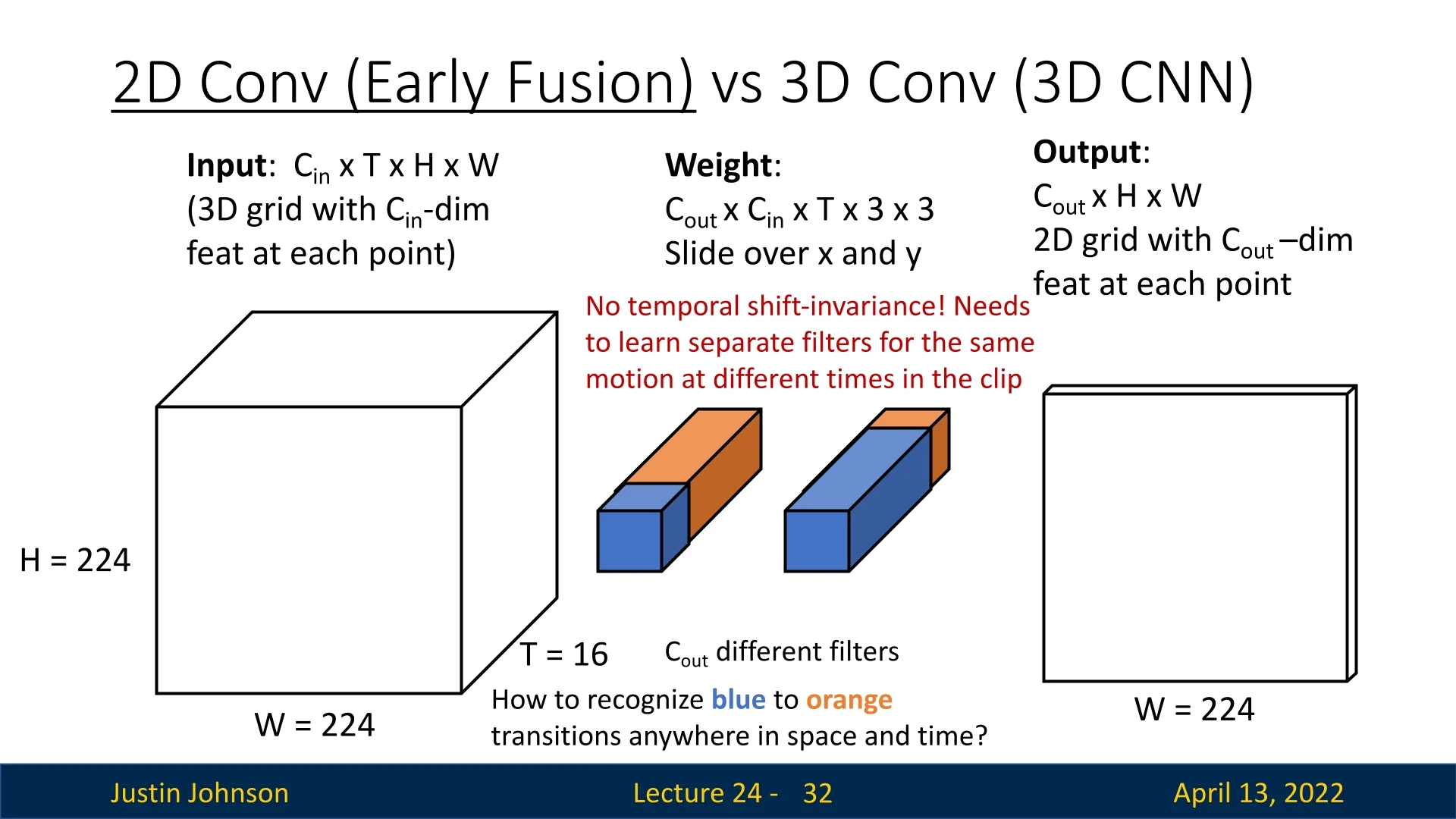

Early fusion (2D convolutions on stacked frames): Frames are concatenated along the channel dimension and processed by a 2D convolution. First-layer filters therefore have shape \[ C_\mbox{out} \times C_\mbox{in} \times T \times K_h \times K_w. \] Each filter spans the entire temporal extent \(T\). This design has two drawbacks:

- 1.

- No temporal shift invariance: the filter is tied to specific time positions. For example, a filter trained to detect a hand moving to the right between frames 1 and 2 will not automatically generalize to the same motion between frames 3 and 4. A separate set of weights must be learned for each timing.

- 2.

- Parameter inefficiency: since temporal variation must be explicitly memorized at different offsets, many more filters are needed to cover the same set of motions. This makes early fusion prone to overfitting and less data-efficient.

- 3D convolution (true spatiotemporal kernels): Filters extend over a limited temporal window \(K_t \ll T\), with shape \[ C_\mbox{out} \times C_\mbox{in} \times K_t \times K_h \times K_w. \] These filters slide along the temporal axis, just as 2D filters slide spatially. This provides temporal shift invariance: once a kernel has learned to detect a short motion pattern (e.g., a flick or edge moving across frames), it will activate regardless of where in the sequence that motion occurs. This is analogous to translation invariance in images, but extended into the time dimension.

For visual clarity, Justin Johnson illustrates these concepts with concrete examples. Early fusion requires separate filters to detect the same phenomenon (in the example, color transition from orange\(\!\to \!\)blue) at different times in the sequence, whereas 3D convolution achieves this with a single filter that generalizes across temporal positions.

Clarifying Input Channels vs Temporal Dimension Convolutions always combine all input channels (\(C_\mbox{in}\), e.g. RGB) at once. The real difference between 2D and 3D convolutions is whether the temporal axis is collapsed or preserved, which changes the filter shape and what it can learn.

- 2D convolution (early fusion): Input: \((C_\mbox{in}\!\cdot \!T) \times H \times W\). Filter: \(C_\mbox{out} \times (C_\mbox{in}\!\cdot \!T) \times K_h \times K_w\). The filter is 2D in space (\(K_h \times K_w\)), but its depth spans all channels, including stacked frames. Thus, time is baked into channels. The network sees all frames at once but cannot reuse the same filter across time; it must learn separate filters for motion at different temporal positions.

- 3D convolution: Input: \(C_\mbox{in} \times T \times H \times W\). Filter: \(C_\mbox{out} \times C_\mbox{in} \times K_t \times K_h \times K_w\). The filter is volumetric: it spans \(K_t\) consecutive frames as well as \(K_h \times K_w\) spatial pixels. Crucially, it slides across time, height, and width. This preserves temporal structure and gives temporal shift invariance: the same filter can detect a motion pattern (e.g., a color change or edge movement) regardless of when it occurs in the sequence.

Practical implication. In early fusion (2D), the model treats the clip like a single thick image: temporal order is fixed, and motion is hard to generalize. In 3D convolution, the model treats the clip as a video volume: filters move through time as well as space, making them natural motion detectors.

24.2.6 Sports-1M Dataset and Baseline Comparisons

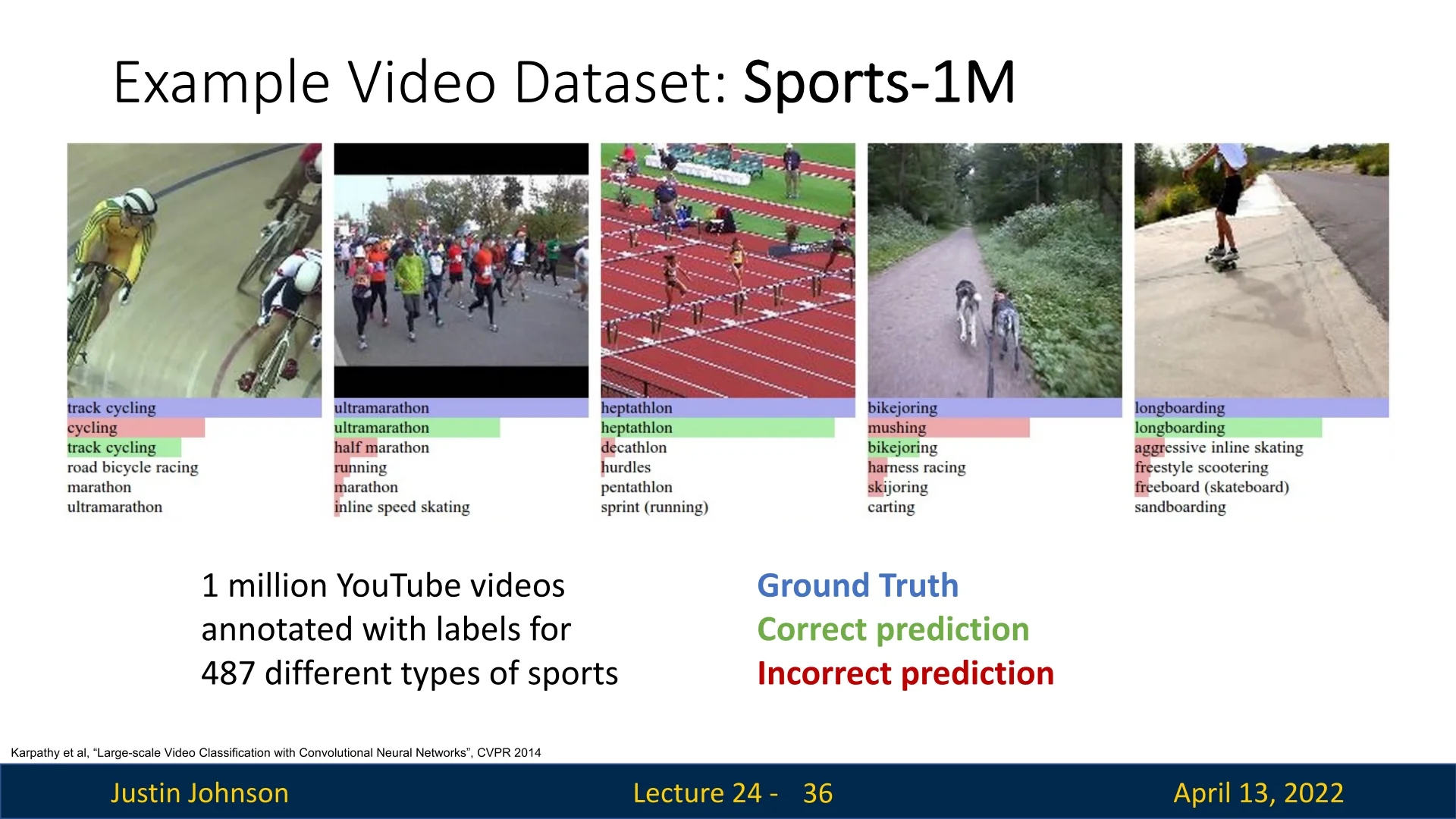

An influential benchmark for video classification is the Sports-1M dataset [276]. It consists of roughly one million YouTube videos labeled across 487 sports categories, ranging from common activities like basketball or soccer to highly fine-grained distinctions such as ultramarathon versus half marathon. The dataset poses unique challenges, as models must not only recognize broad classes of motion but also discriminate subtle variations within closely related activities.

These examples illustrate the dataset’s difficulty: coarse categories are often recognized correctly, but small variations in equipment, environment, or motion patterns can determine the correct label. As a result, fine-grained sports categories highlight the challenge of models trained on video data.

24.2.7 Baseline Model Performance

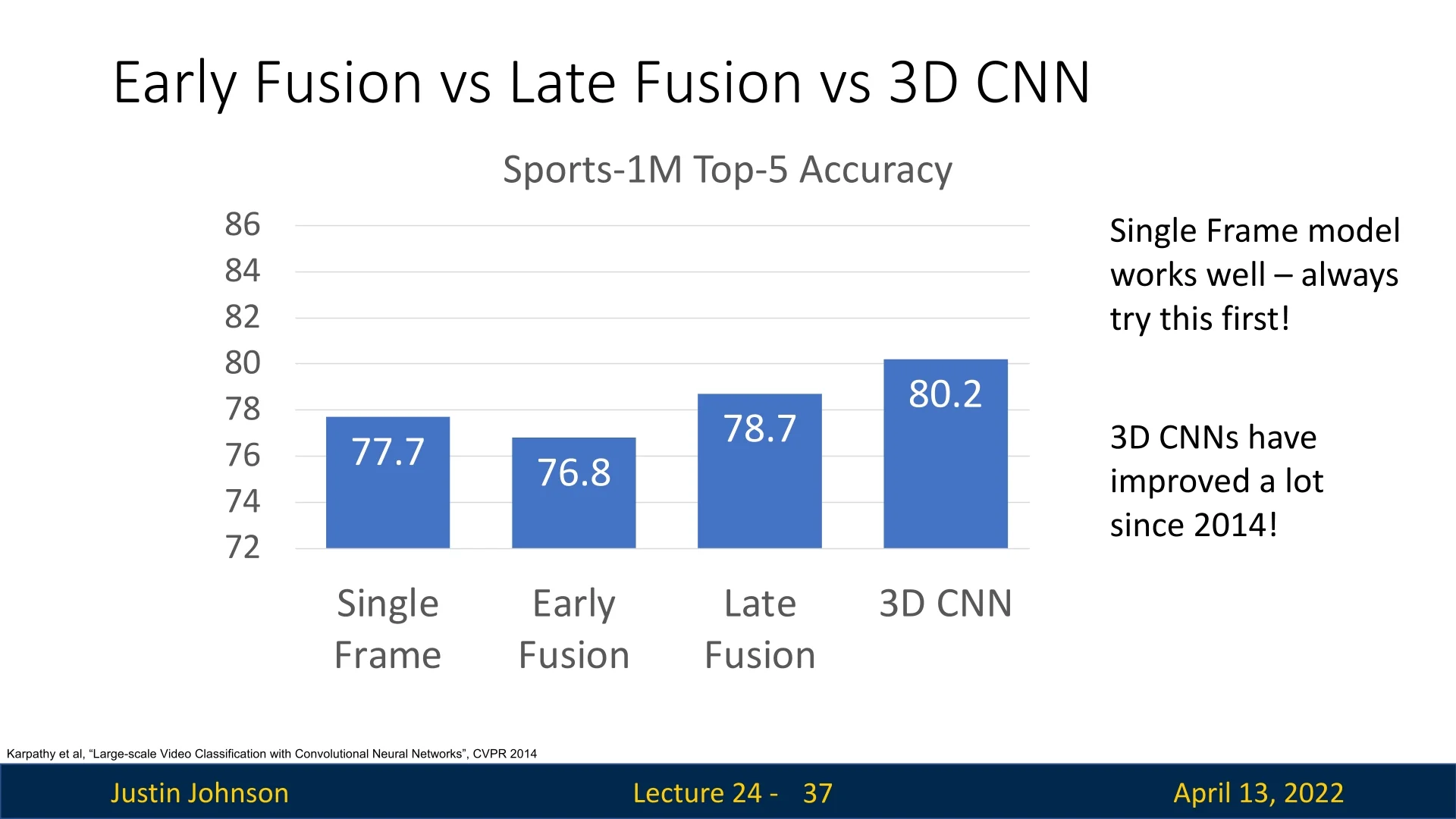

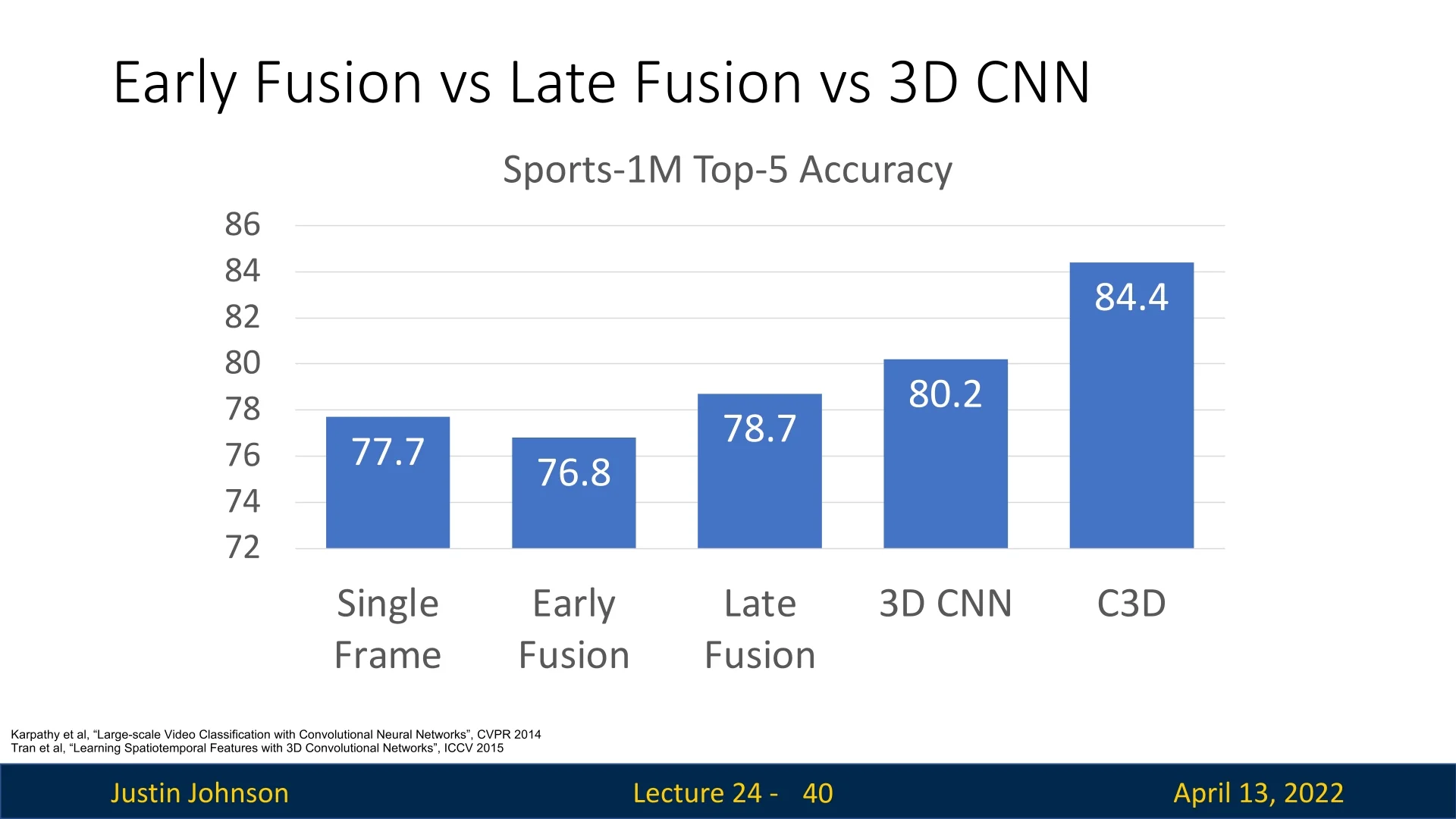

Karpathy et al. [276] benchmarked several architectures on Sports-1M, comparing single-frame CNNs, early fusion, late fusion, and 3D CNNs (slow fusion). Surprisingly, the single-frame baseline outperformed early fusion, achieving \(77.7\%\) accuracy compared to \(76.8\%\). Late fusion and 3D CNNs provided modest improvements, with \(78.7\%\) and \(80.2\%\) respectively.

These results underscore two key insights:

- 1.

- Single-frame models are strong baselines: even ignoring temporal structure, per-frame CNNs achieve competitive accuracy, making them a practical first step for many applications.

- 2.

- Temporal models offer incremental gains: incorporating temporal reasoning via late fusion or 3D CNNs provides improvements, but the gap is smaller than might be expected.

It is important to note that these experiments date back to 2014, when training resources and architectures were limited (many models were trained on CPU clusters). Since then, 3D CNN architectures and large-scale training pipelines have advanced significantly, so the reported numbers should be interpreted with caution.

24.2.8 C3D: The VGG of 3D CNNs

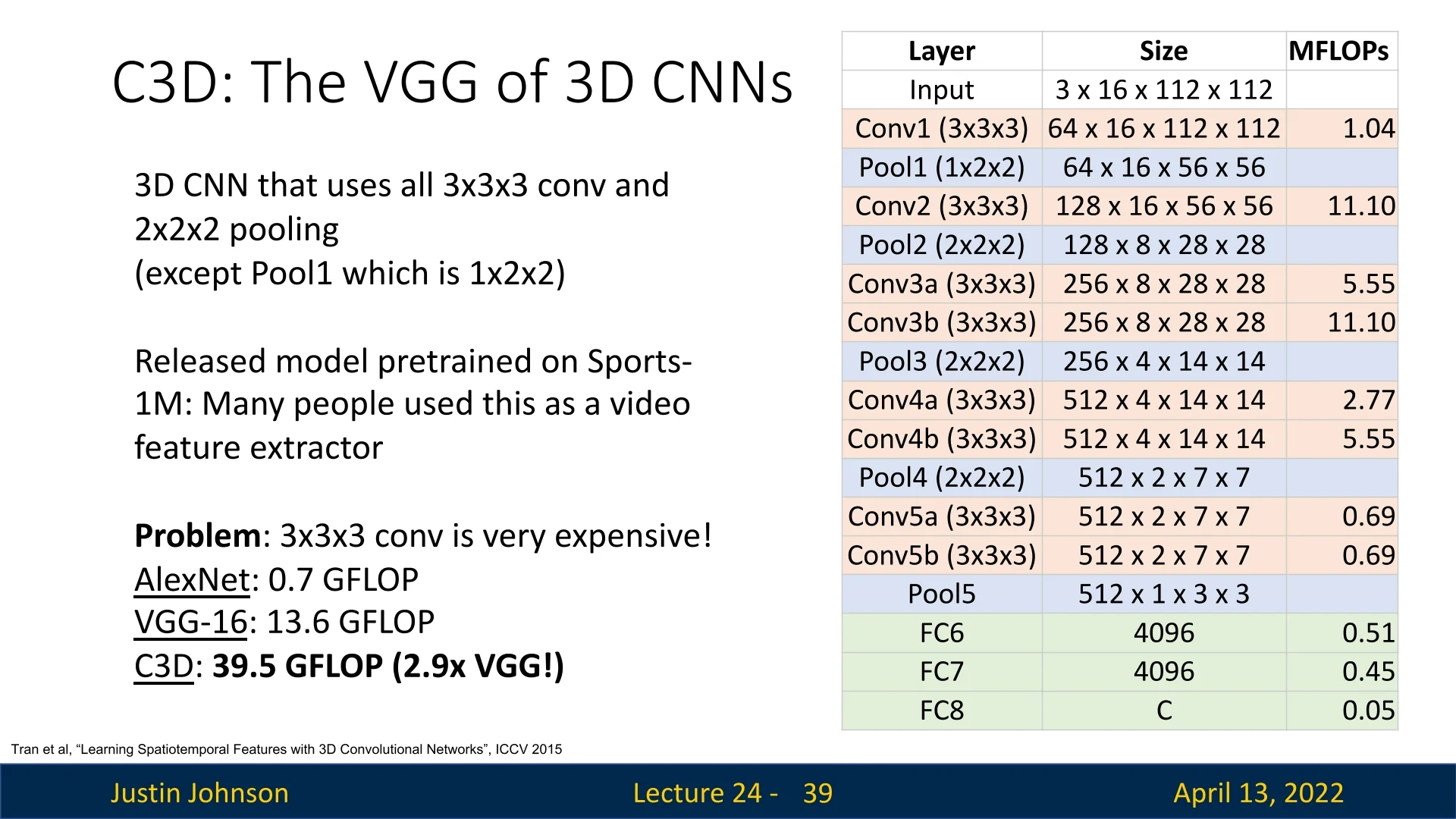

A landmark architecture in early video understanding was the C3D network [631], often described as “the VGG of 3D CNNs”. Recall that VGG for images was built entirely from \(3 \times 3\) convolutions and \(2 \times 2\) poolings in a simple conv–conv–pool pattern. C3D extended this idea to videos: it used \(3 \times 3 \times 3\) convolutions and \(2 \times 2 \times 2\) poolings throughout, except in the first pooling layer, which used \(1 \times 2 \times 2\) to avoid collapsing the temporal dimension too early.

This design made C3D a straightforward 3D analog of VGG and an influential baseline in the field. Importantly, the authors released pretrained weights on Sports-1M, and many subsequent works used C3D as a fixed video feature extractor.

Computation cost The main drawback of C3D is its cost. Even with small inputs (16 frames of size \(112 \times 112\)), a single forward pass requires nearly 40 GFLOPs:

- AlexNet: \(0.7\) GFLOPs

- VGG-16: \(13.6\) GFLOPs

- C3D: \(39.5\) GFLOPs

This stems from sliding 3D kernels over the entire spatiotemporal volume, which scales cubically in kernel size.

Summary The story of C3D parallels that of image models: accuracy improved by scaling up deeper, more expensive networks. But these architectures also highlighted the need to treat time and space differently, rather than as fully interchangeable.

24.3 Separating Time and Space in 3D Processing

Humans are capable of recognizing actions from motion cues alone. For example, point-light displays of moving dots are sufficient for us to perceive walking, running, or waving. This suggests that the brain processes motion and appearance in distinct ways. Motivated by this, researchers proposed architectures that explicitly disentangle motion from appearance inside the network.

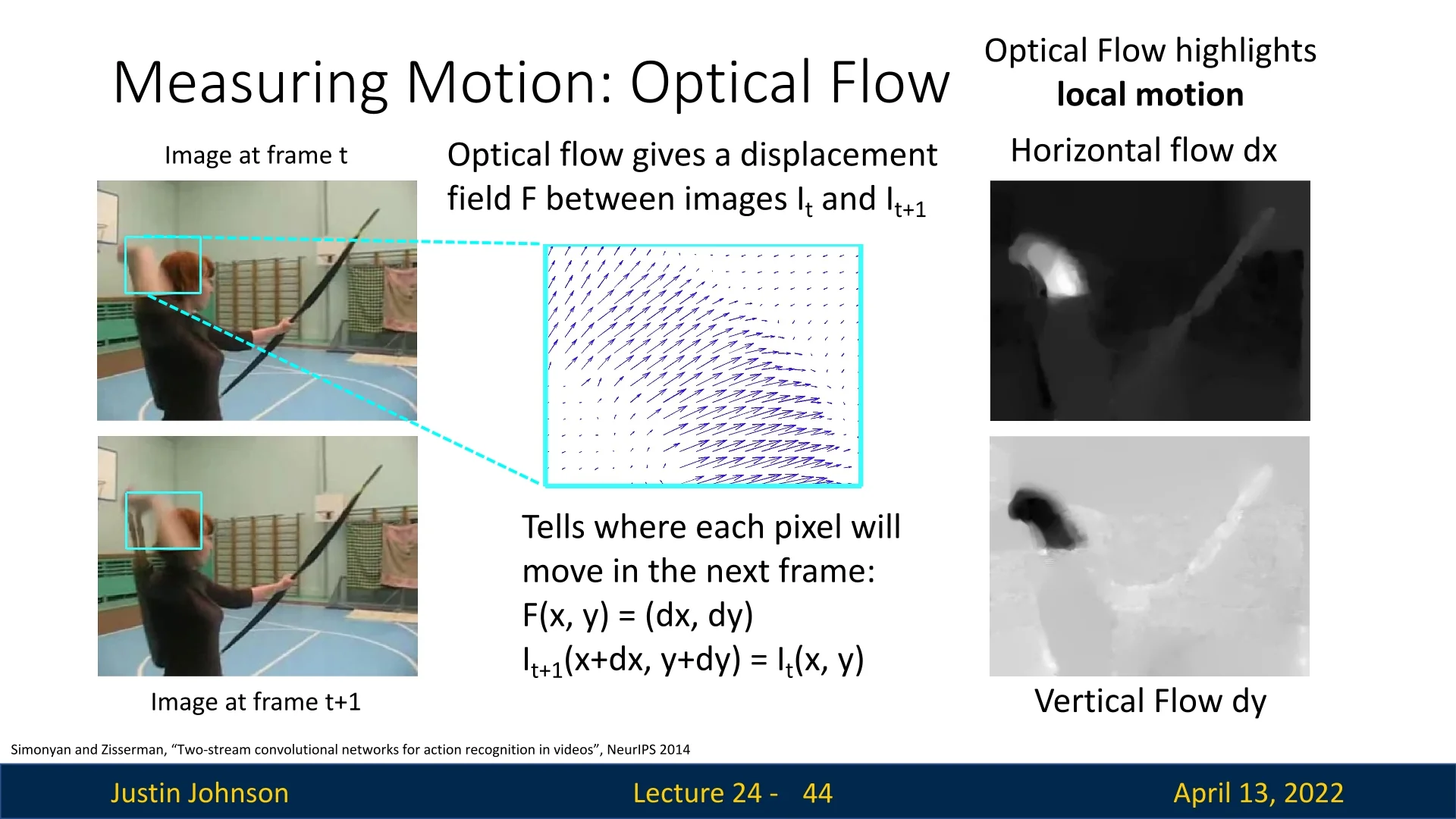

24.3.1 Measuring Motion: Optical Flow

A widely used way to represent motion in videos is through optical flow. At a high level, optical flow estimates how points in one frame move to their new positions in the next frame. \[ F(x,y) = (d_x, d_y), \quad I_{t+1}(x+d_x, y+d_y) \approx I_t(x,y), \] The output is a vector field where \((d_x,d_y)\) is the estimated displacement of the pixel at \((x,y)\) from time \(t\) to \(t+1\). Intuitively, this captures local motion: if an object moves to the right, nearby vectors in the flow field will all point rightward with magnitude proportional to the speed.

Dense vs. sparse flow Optical flow can be dense, with a displacement vector for every pixel, or sparse, with vectors only at keypoints. Dense flow captures detailed motion everywhere, while sparse flow is cheaper and focuses on stable regions.

Why this helps Unlike raw RGB values, which encode only appearance, optical flow provides an explicit description of how things move. This allows models to disentangle appearance (what is present) from motion (how it changes). For example, in an action like “shooting a bow,” the background may be irrelevant, but the flow highlights the arm and bow movement. Feeding these motion fields into CNNs complements RGB inputs and improves video understanding.

24.3.2 Two-Stream Networks

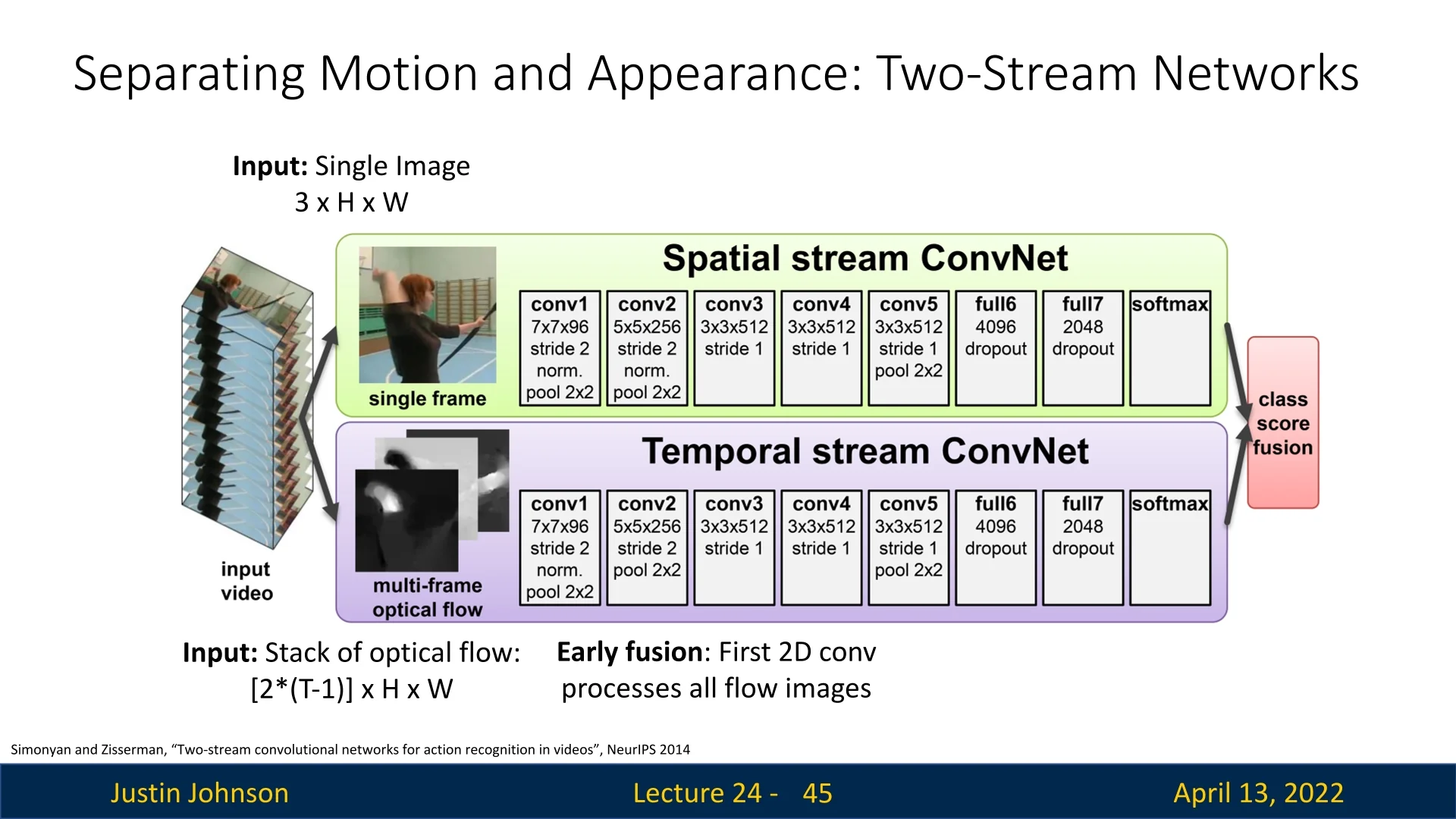

A seminal architecture exploiting this idea is the two-stream network of Simonyan and Zisserman [571]. It consists of two parallel CNN branches:

- Spatial stream: Processes single RGB frames to capture appearance. Each frame is classified independently, and predictions are averaged over \(T\) frames.

- Temporal stream: Processes stacked optical flow fields. From \(T\) frames, there are \(T-1\) optical flows, each with two channels (horizontal and vertical), yielding a tensor of shape \([2(T-1)] \times H \times W\). Early fusion at the first convolution combines motion across frames, followed by standard 2D CNN layers.

At test time, both streams output class distributions. The final prediction is obtained by averaging, or by training an SVM over the concatenated outputs.

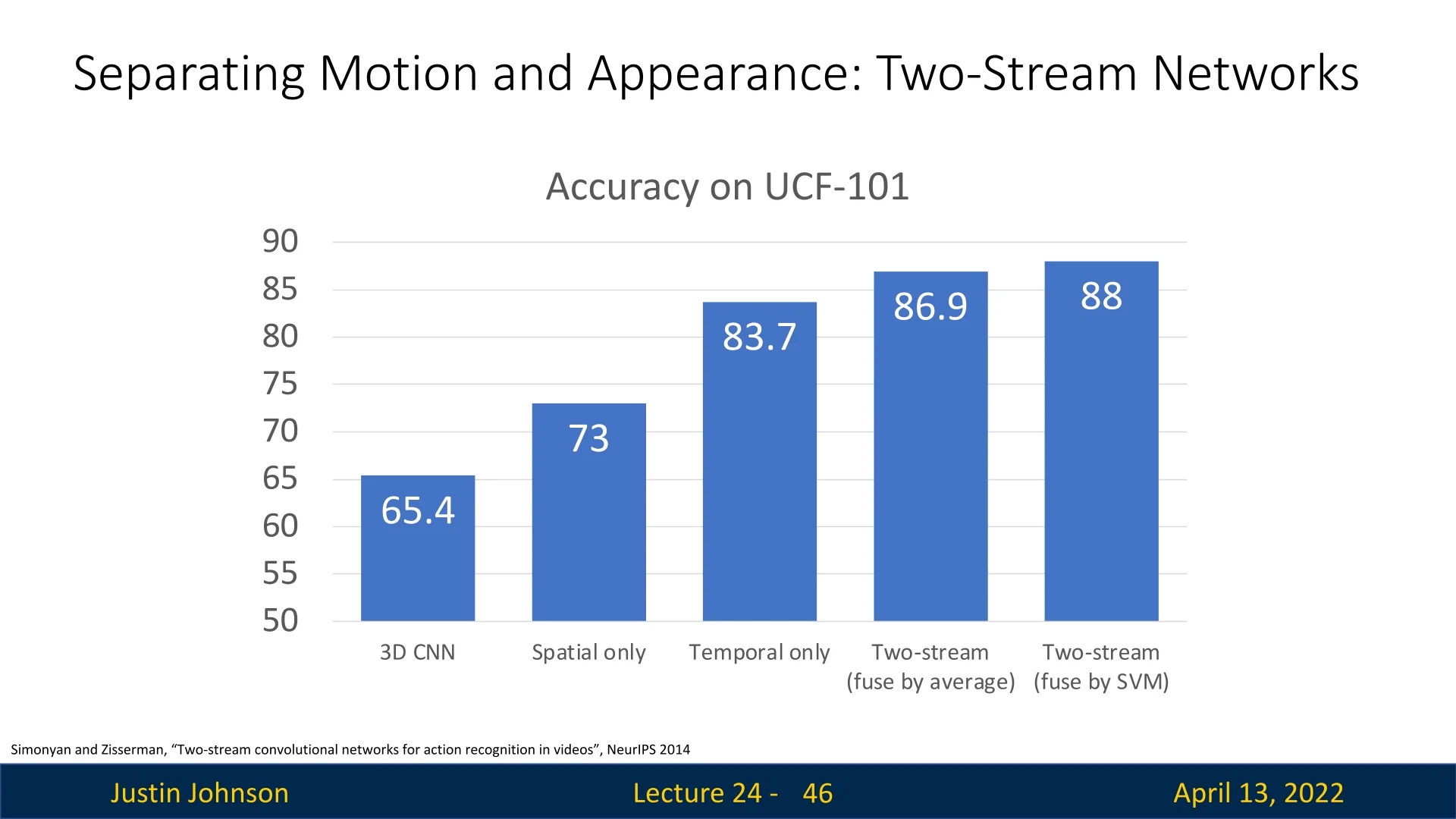

Evaluation on UCF-101

The two-stream model was evaluated on the UCF-101 dataset. Results show clear advantages of separating appearance and motion:

- 3D CNN: \(65.4\%\)

- Spatial-only stream: \(73.0\%\)

- Temporal-only stream: \(83.7\%\)

- Two-stream, average fusion: \(86.9\%\)

- Two-stream, SVM fusion: \(88.0\%\)

These results highlight that motion is often more informative than raw appearance, but the best performance arises when both are combined.

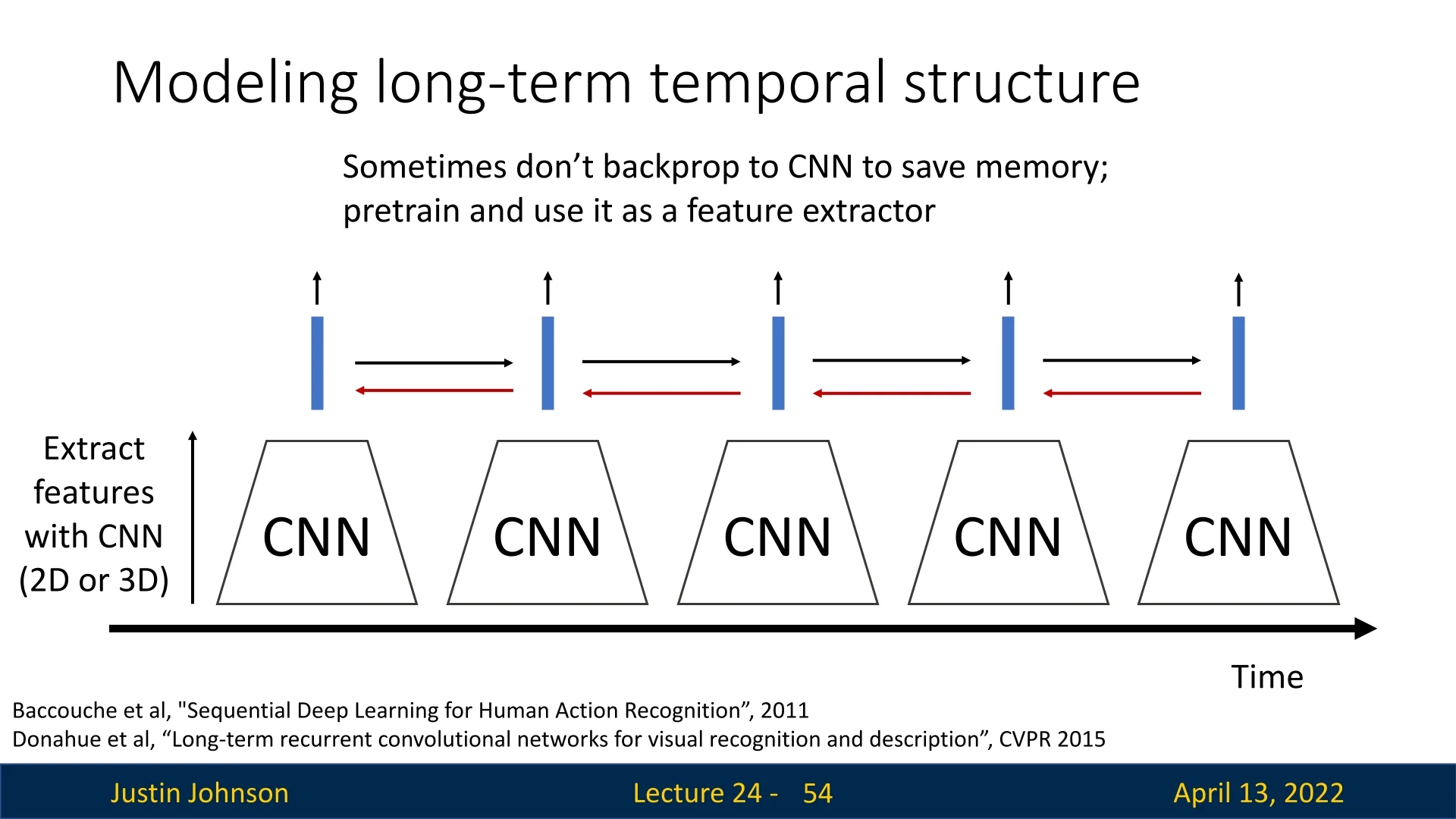

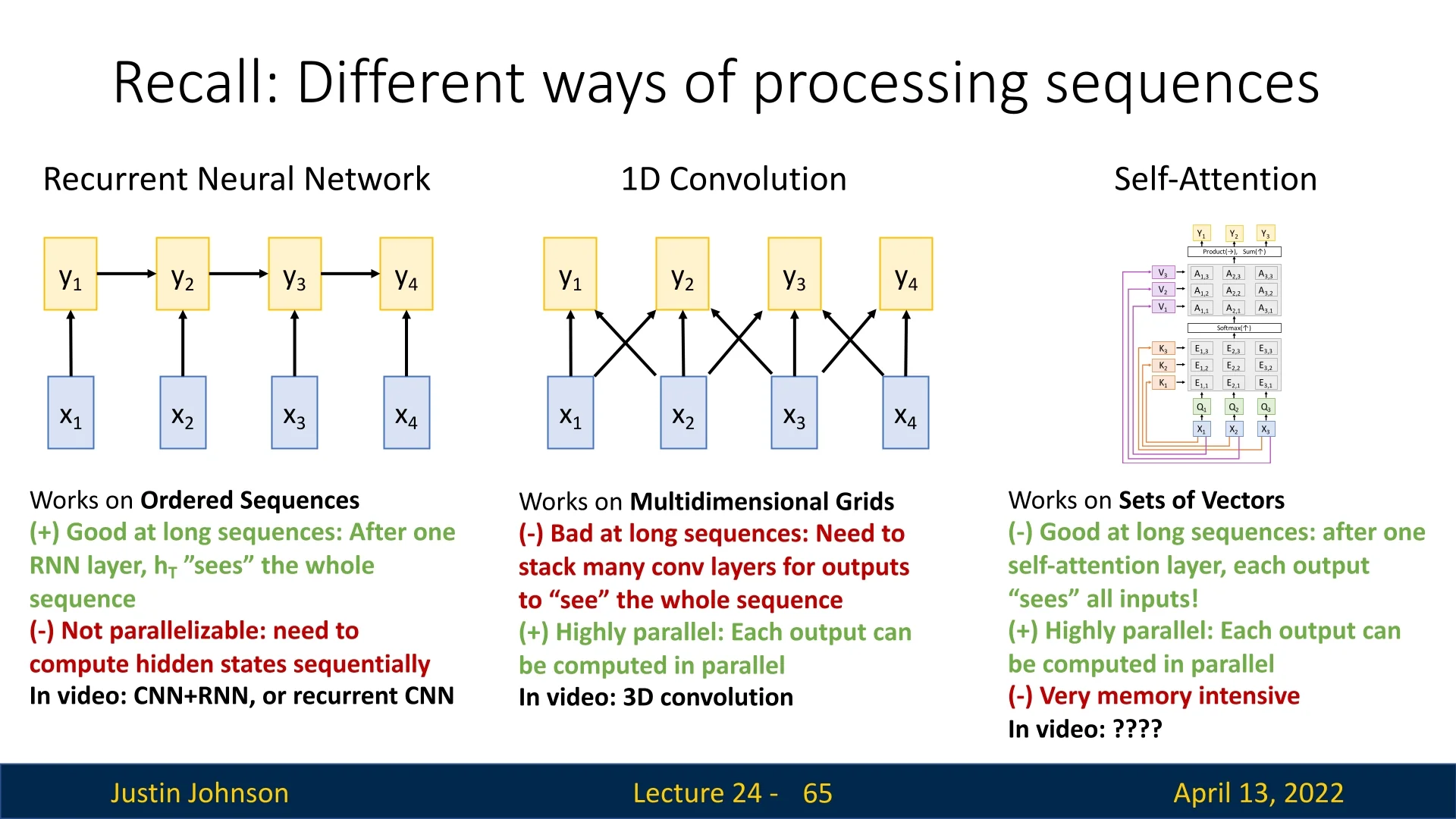

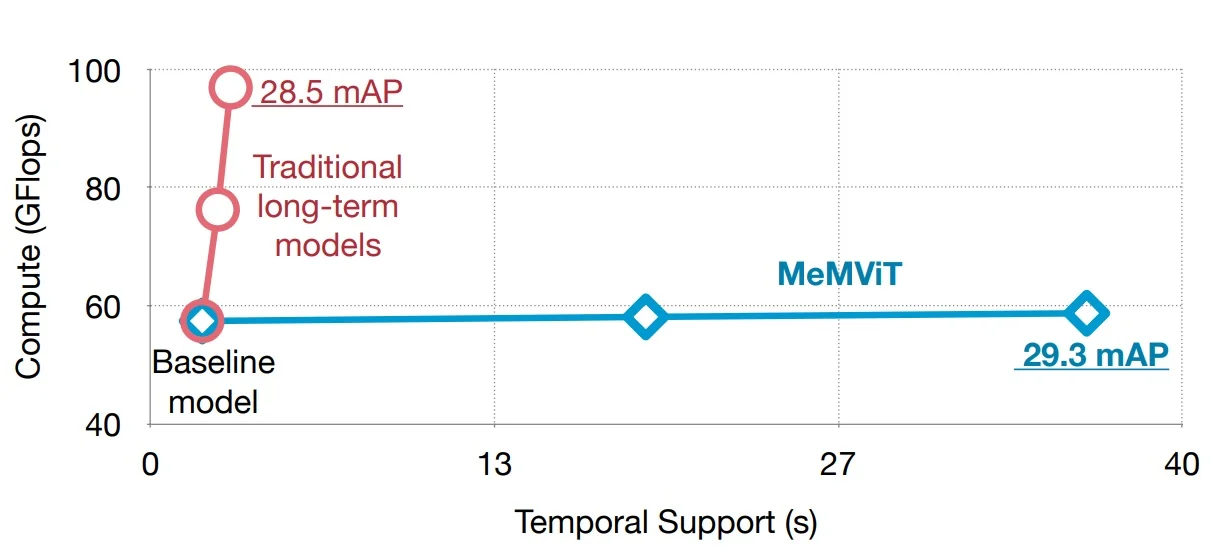

24.4 Modeling Long-Term Temporal Structure

Most architectures discussed so far capture only local temporal patterns: 2D or 3D CNNs operate on short clips of \(\sim \)16–32 frames. Many tasks, however, require reasoning about long-term dependencies, where informative events are separated by seconds or minutes. We therefore seek models that aggregate information across extended time spans while preserving strong spatial representations.

24.4.1 CNN Features + Recurrent Networks

A practical recipe is to pair CNNs for spatial and short-term modeling with RNNs:

- 1.

- Extract per-timestep features with a CNN (2D on frames or 3D on short clips), yielding a feature vector at each step.

- 2.

- Feed the feature sequence to a recurrent model (e.g., LSTM) to aggregate over time.

- 3.

- For video-level classification, use a many-to-one mapping from the final hidden state; for dense labeling, use many-to-many by reading out from all hidden states.

This idea appeared early in Baccouche et al. [21] and was popularized by Donahue et al. with Long-term Recurrent Convolutional Networks (LRCN) [131]. A memory-efficient variant freezes the clip-level CNN (e.g., C3D) and trains only the RNN to cover long time horizons without backpropagating through very long video volumes.

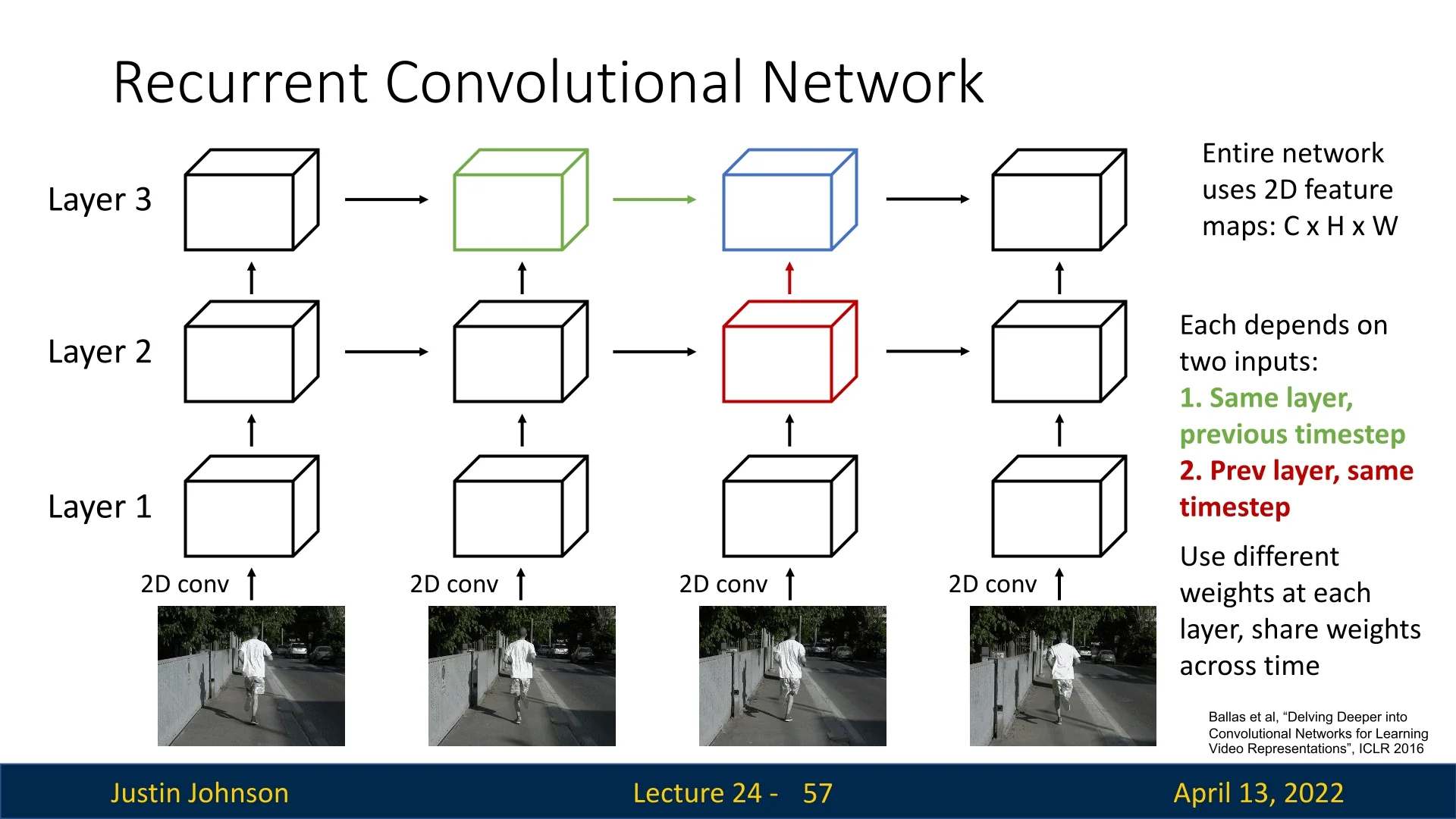

From vector RNNs to recurrent convs Multi-layer RNNs stack temporal processing; the state at time \(t\) in layer \(l\) depends on the state at \((t{-}1,l)\) and on input from \((t,l{-}1)\). The same idea can be applied inside convolutional networks by replacing matrix multiplications with convolutions, yielding recurrent convolutional networks in which each spatial location behaves like a tiny RNN through time [27].

Gated variants and practicality As with standard sequence models, one can replace simple recurrences with GRU or LSTM-style convolutional gates. While elegant, such models inherit the sequential dependency of RNNs, limiting parallelism and slowing training on long videos.

24.4.2 Spatio-Temporal Self-Attention and the Nonlocal Block

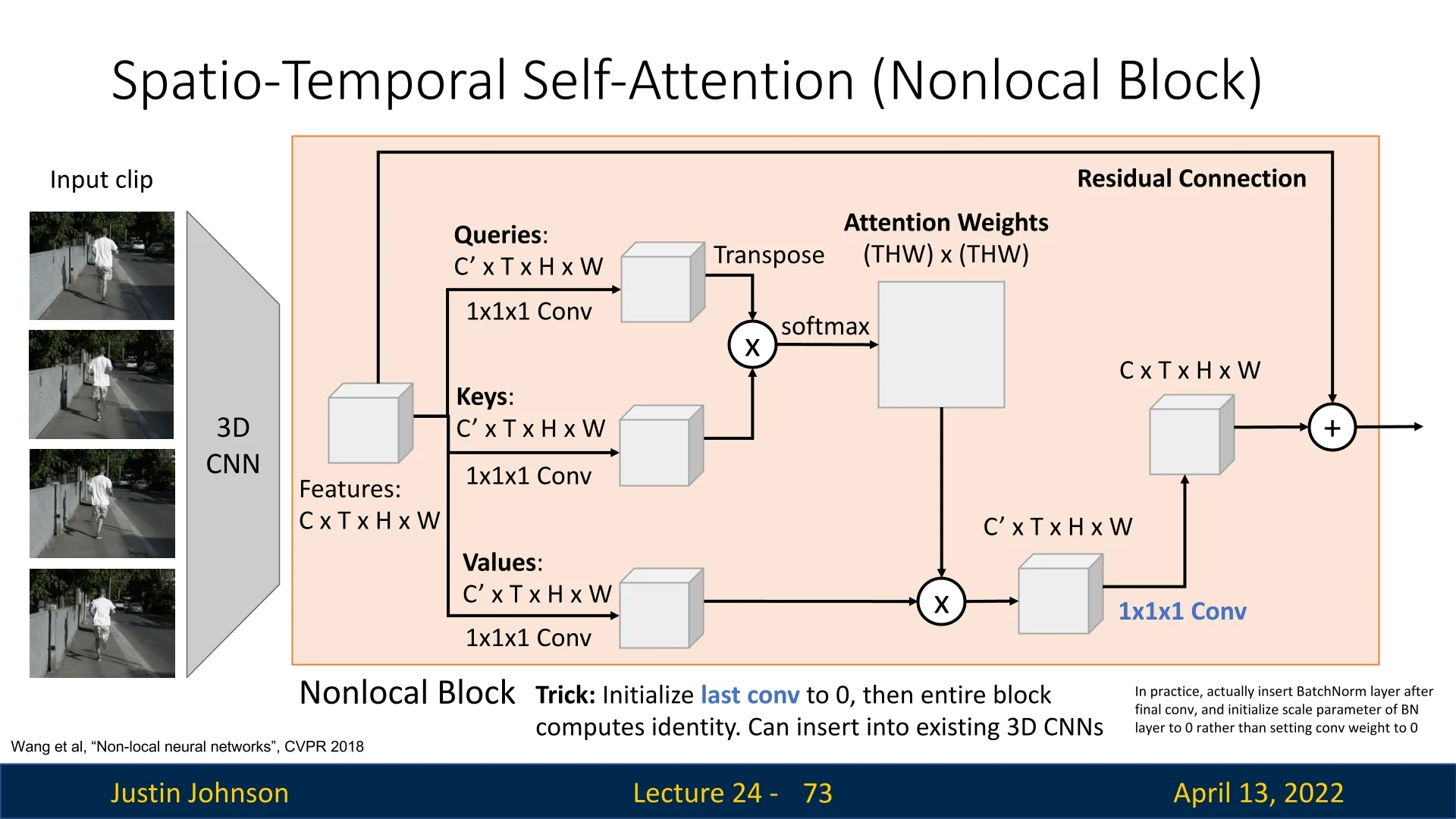

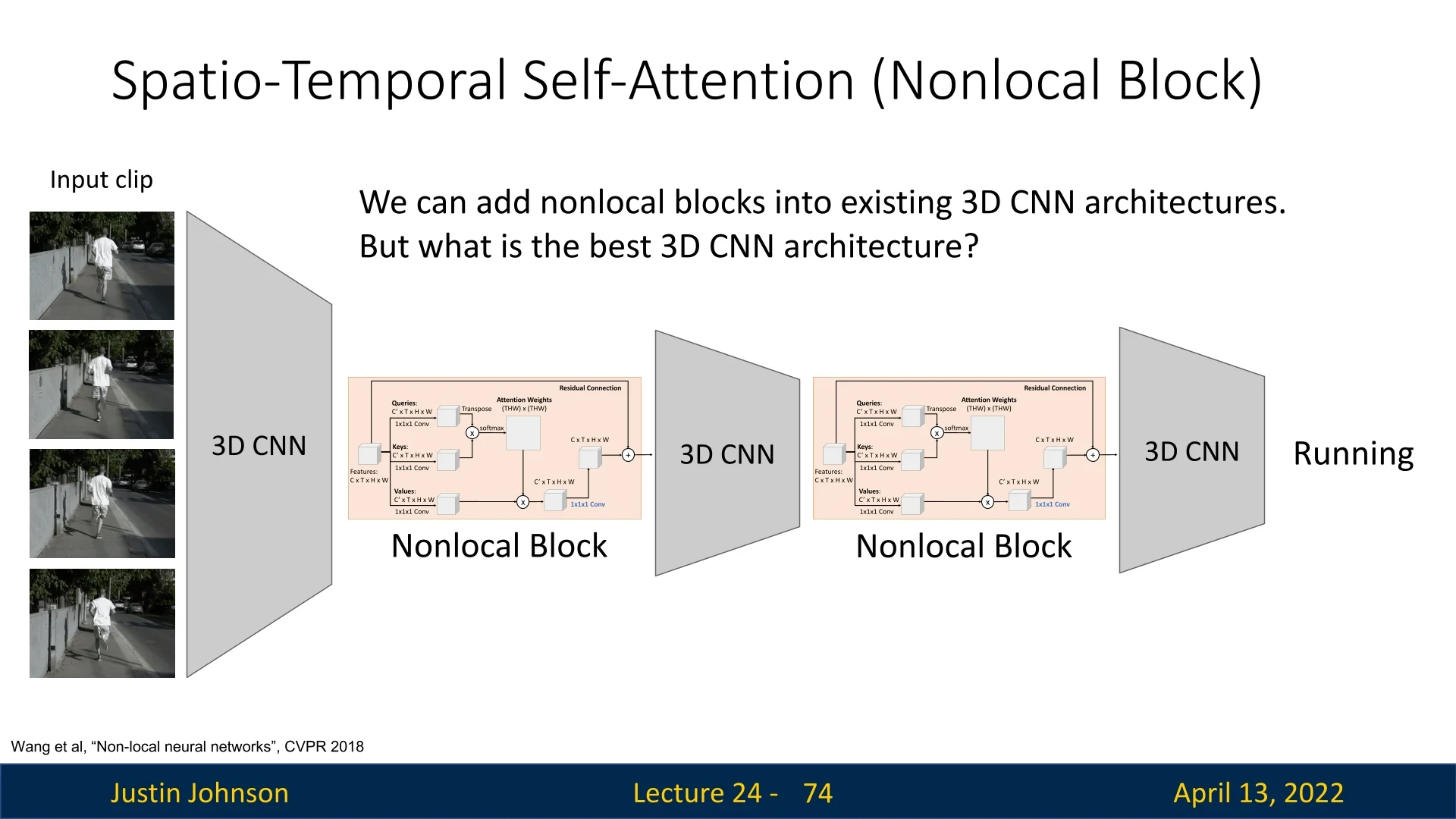

Standard 3D CNNs operate on local neighborhoods in space and time; relating distant events requires many layers to propagate information. To address this, Wang et al. [675] proposed the nonlocal block, a spatio-temporal self-attention module that directly connects all positions in a video volume.

Definition Given input features: \begin {equation} \label {eq:chapter24_nonlocal_input} \mathbf {X} \in \mathbb {R}^{C \times T \times H \times W}, \end {equation} the block computes queries, keys, and values via \(1{\times }1{\times }1\) convolutions, \begin {equation} \label {eq:chapter24_nonlocal_qkv} \mathbf {Q},\mathbf {K},\mathbf {V} \in \mathbb {R}^{C' \times T \times H \times W}, \end {equation} flattens space–time so \(N{=}T\!\cdot \!H\!\cdot \!W\), forms affinities \begin {equation} \label {eq:chapter24_nonlocal_attn} \mathbf {A}=\mbox{softmax}\!\big (\mathbf {Q}^\top \mathbf {K}\big )\in \mathbb {R}^{N\times N},\quad \sum _j \mathbf {A}_{ij}=1, \end {equation} aggregates values \begin {equation} \label {eq:chapter24_nonlocal_agg} \mathbf {Y}=\mathbf {V}\,\mathbf {A}^\top \in \mathbb {R}^{C'\times N}, \end {equation} reshapes back to \(C'\times T\times H\times W\), projects to \(C\) channels with \(W_z\), and adds a residual: \begin {equation} \label {eq:chapter24_nonlocal_residual} \mathbf {Z}=W_z(\mathbf {Y})+\mathbf {X}. \end {equation}

Initialization and integration For stable insertion into 3D CNNs, initialize the final projection so the block starts as identity; in practice, place a BatchNorm after the last \(1{\times }1{\times }1\) and initialize its scale to zero. This yields slow fusion via local 3D convolutions plus global fusion via nonlocal attention.

Takeaway Nonlocal blocks overcome locality constraints of convolutions and the sequential bottleneck of RNNs by enabling each position to directly gather context from anywhere in the video, improving representations for tasks such as action recognition and video classification.

24.4.3 Inflating 2D Networks to 3D (I3D)

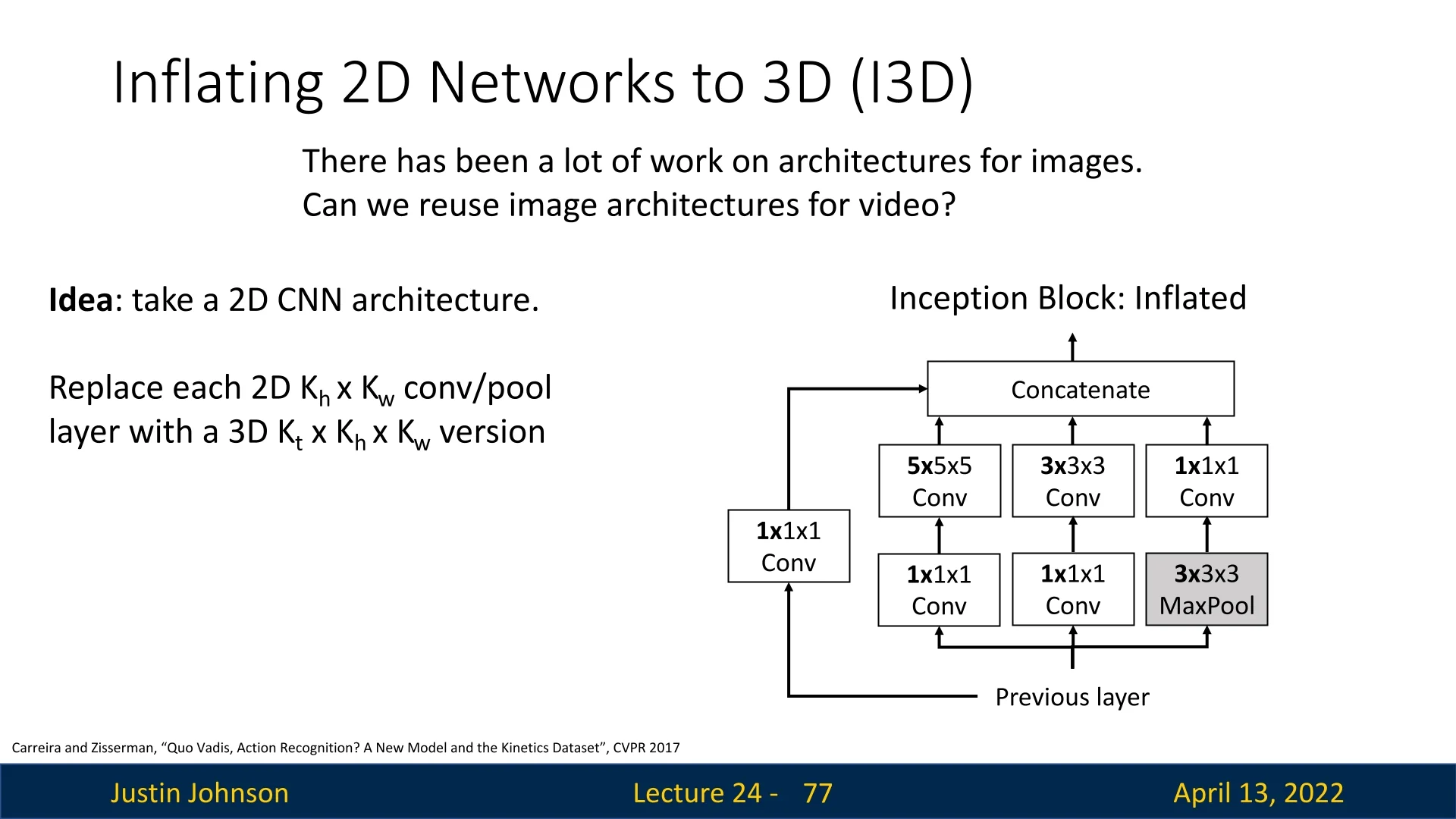

Designing effective 3D CNNs from scratch is costly. I3D [74] addresses this by inflating a strong 2D architecture (e.g., Inception-v1) into 3D so it can process space and time while reusing ImageNet-pretrained weights. The core idea is twofold:

- Inflate the architecture: add a temporal extent \(K_t\) to every operation (convolutions, pooling, etc.), turning \(K_h{\times }K_w\) kernels into \(K_t{\times }K_h{\times }K_w\).

- Inflate the weights: initialize 3D kernels from pretrained 2D kernels by replicating them along the temporal dimension and scaling by \(1/K_t\), so the inflated network behaves identically to the 2D parent on static videos.

Inflating the architecture Every 2D layer is given an explicit temporal kernel size \(K_t\):

- \(K_h{\times }K_w\) conv \(\Rightarrow \) \(K_t{\times }K_h{\times }K_w\) conv, same for pooling.

- Inception branches and residual pathways are expanded analogously, preserving topology and receptive-field design.

- Temporal stride and padding are chosen to control temporal downsampling and receptive-field growth, mirroring spatial design.

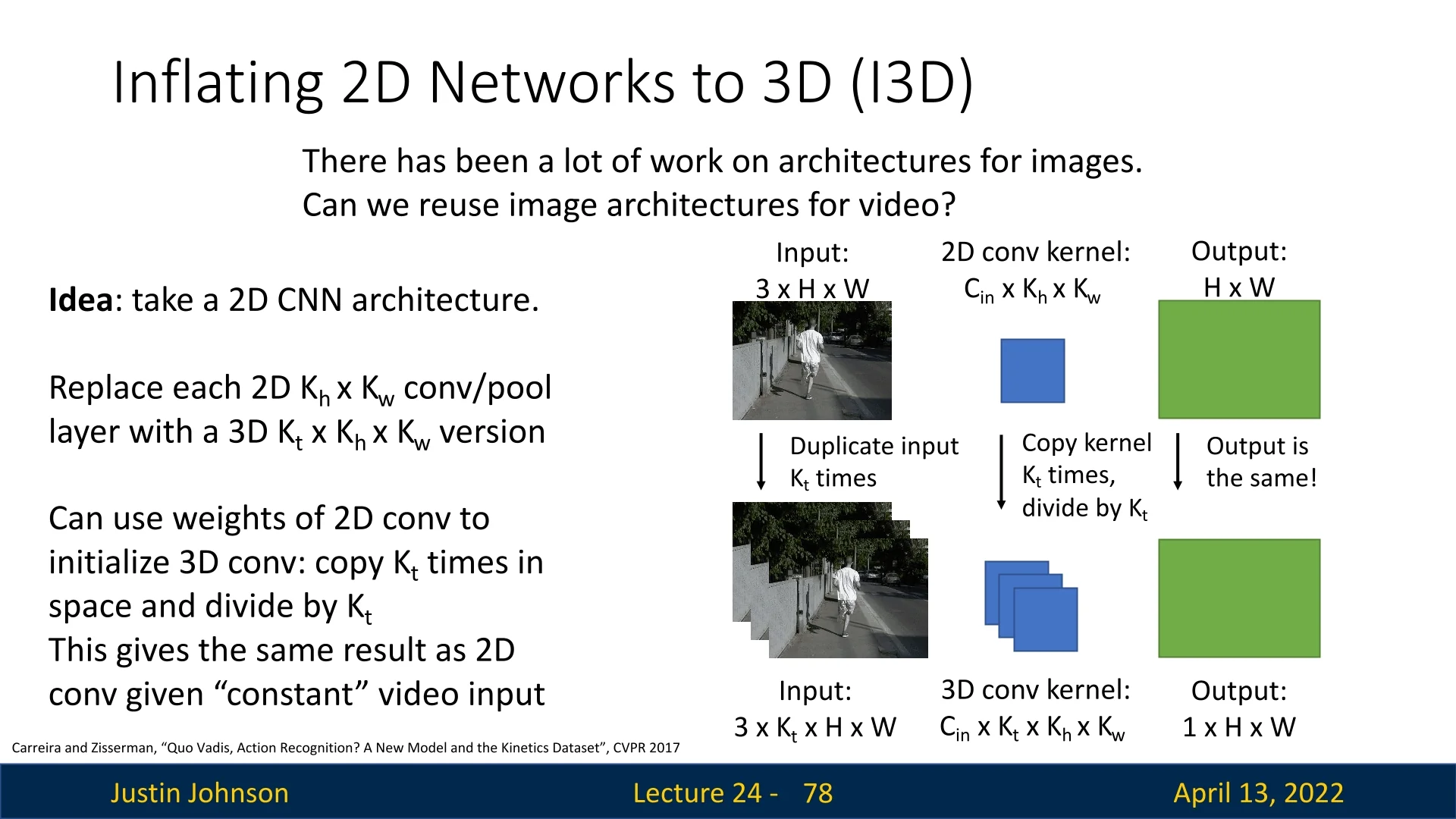

Inflating the weights: replication and normalization Let a 2D filter be \(W_{2D}\!\in \!\mathbb {R}^{C_\mbox{out}\times C_\mbox{in}\times K_h\times K_w}\) and its inflated 3D filter be \(W_{3D}\!\in \!\mathbb {R}^{C_\mbox{out}\times C_\mbox{in}\times K_t\times K_h\times K_w}\). I3D initializes \begin {equation} \label {eq:chapter24_i3d_weight_inflate} W_{3D}[:,:,t,:,:] \;=\; \tfrac {1}{K_t}\, W_{2D} \quad \mbox{for } t=1,\dots ,K_t. \end {equation} That is, replicate the 2D kernel along time and divide by \(K_t\). The division prevents an unintended \(K_t\)-fold amplification of responses.

Why divide by \(K_t\) Consider a static video \(I\) where every frame is identical. A 3D convolution with the replicated kernel computes a temporal sum of identical 2D responses. Without normalization, \[ \mbox{Conv3D}(W_{3D}, I) \;=\; \sum _{t=1}^{K_t}\mbox{Conv2D}(W_{2D}, I) \;=\; K_t\,\mbox{Conv2D}(W_{2D}, I). \] Scaling by \(1/K_t\) in (24.9) cancels this factor, yielding \[ \mbox{Conv3D}(W_{3D}, I) \;=\; \mbox{Conv2D}(W_{2D}, I), \] so the inflated 3D layer is exactly equivalent to the original 2D layer on static inputs. This preserves activation magnitudes and the semantics of pretrained features at initialization, which is crucial for stability with BatchNorm and deep stacks.

Why inflation is a natural fit Videos contain the same spatial structures as images (edges, textures, objects), now evolving over time. Inflation transfers mature spatial detectors from 2D while introducing a neutral temporal prior (identical slices). During fine-tuning, backpropagation learns temporal asymmetries across slices (e.g., detectors of motion direction or temporal phase), turning static spatial filters into motion-sensitive spatiotemporal filters. Thus, optimization focuses on temporal modeling rather than relearning spatial basics.

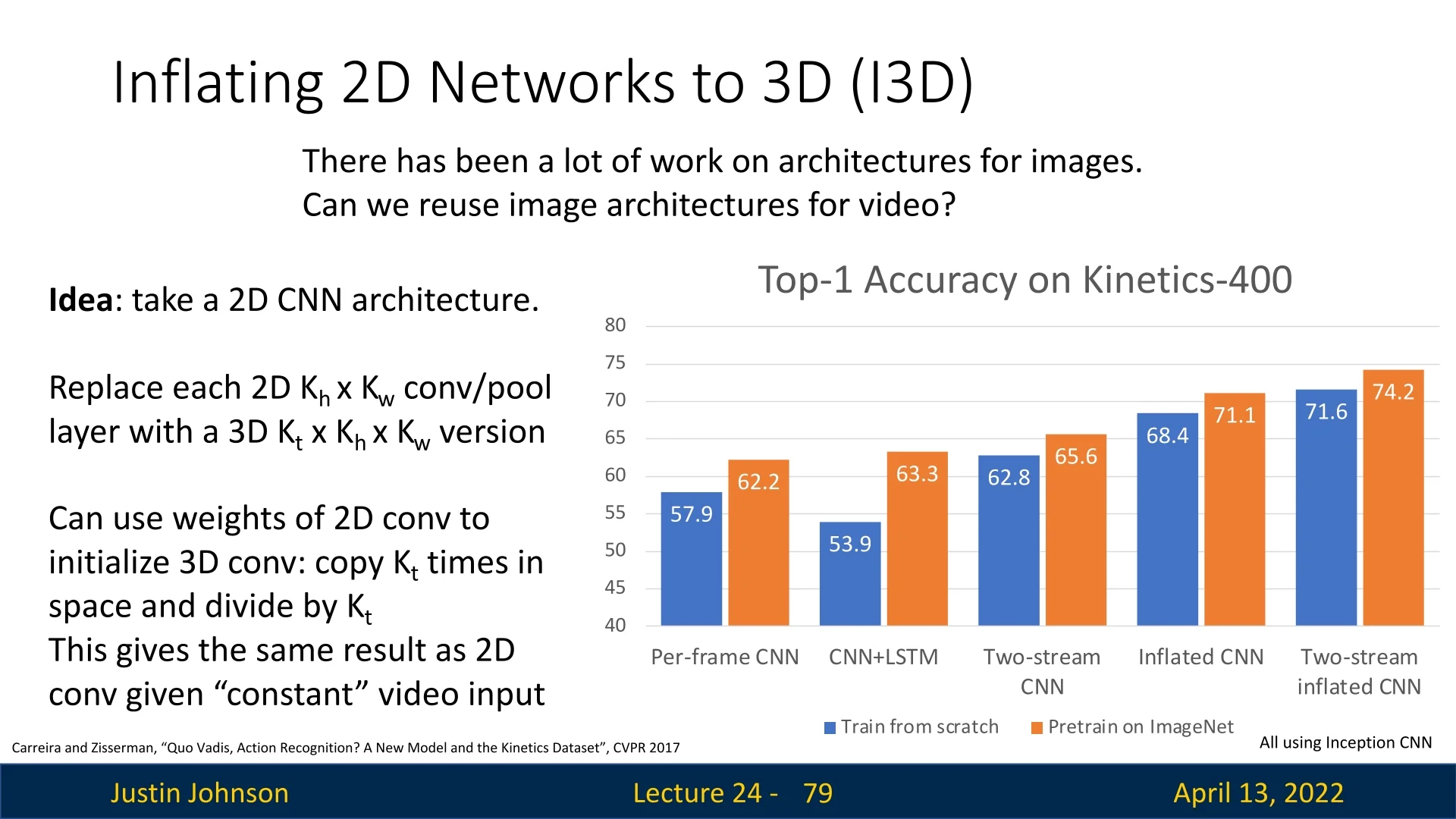

Evidence on Kinetics-400 On Kinetics-400 [282] (300K ten-second YouTube clips across 400 actions), Carreira and Zisserman showed that, with the same Inception-v1 backbone, inflating ImageNet-pretrained weights outperforms training 3D kernels from scratch.

Takeaway I3D provides a principled initialization with several benefits:

- Equivalence on static inputs: the inflated network is provably identical to its 2D parent when frames are constant, ensuring stable initialization.

- Spatial competence transfer: pretrained image filters (e.g., from ImageNet) provide strong recognition of edges, textures, and objects without retraining.

- Focus on temporal dynamics: since spatial features are inherited, optimization capacity can concentrate on learning motion-sensitive filters.

Together, these properties make inflation a strong, data-efficient baseline and a reliable foundation for higher-performing video models.

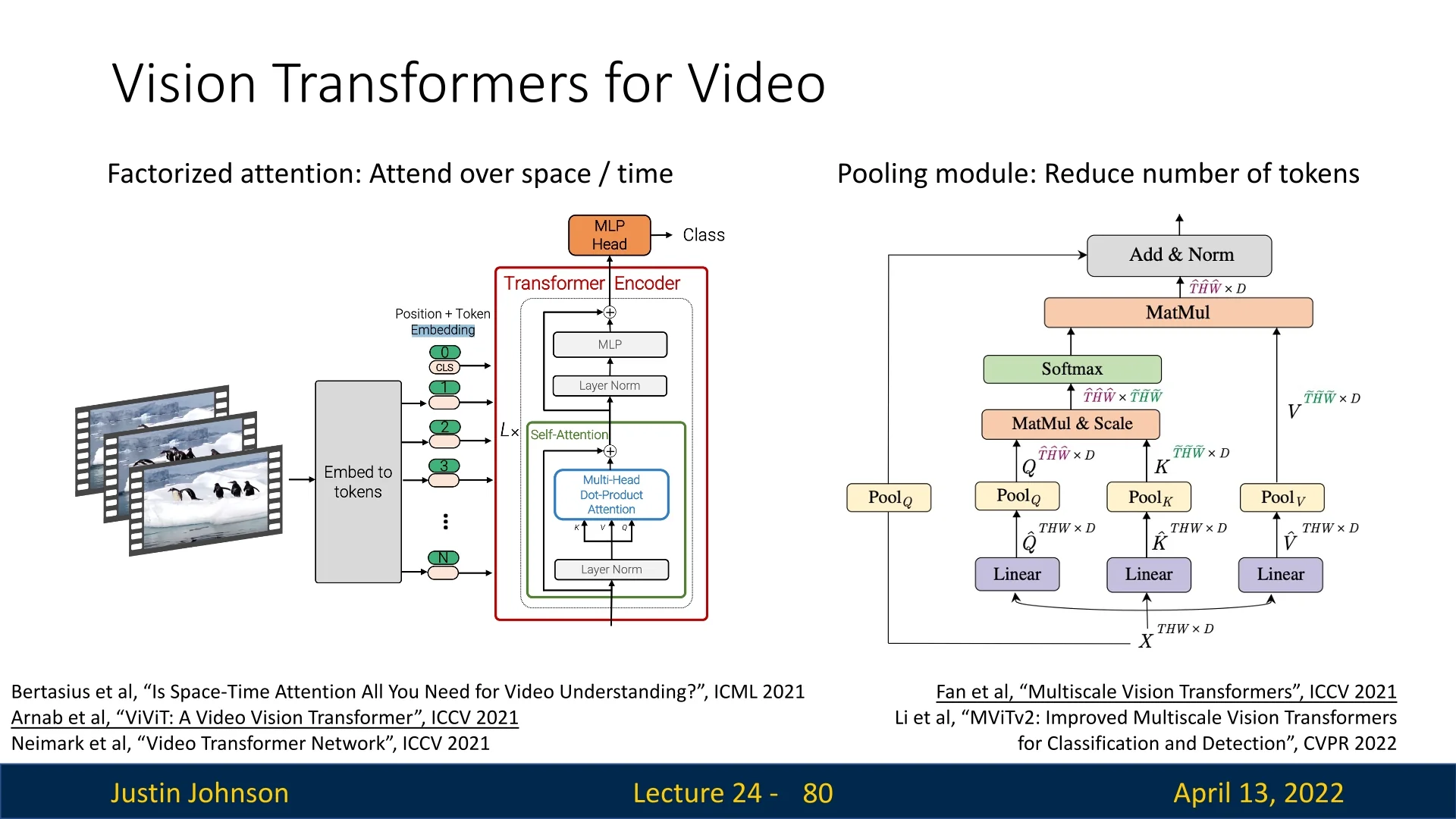

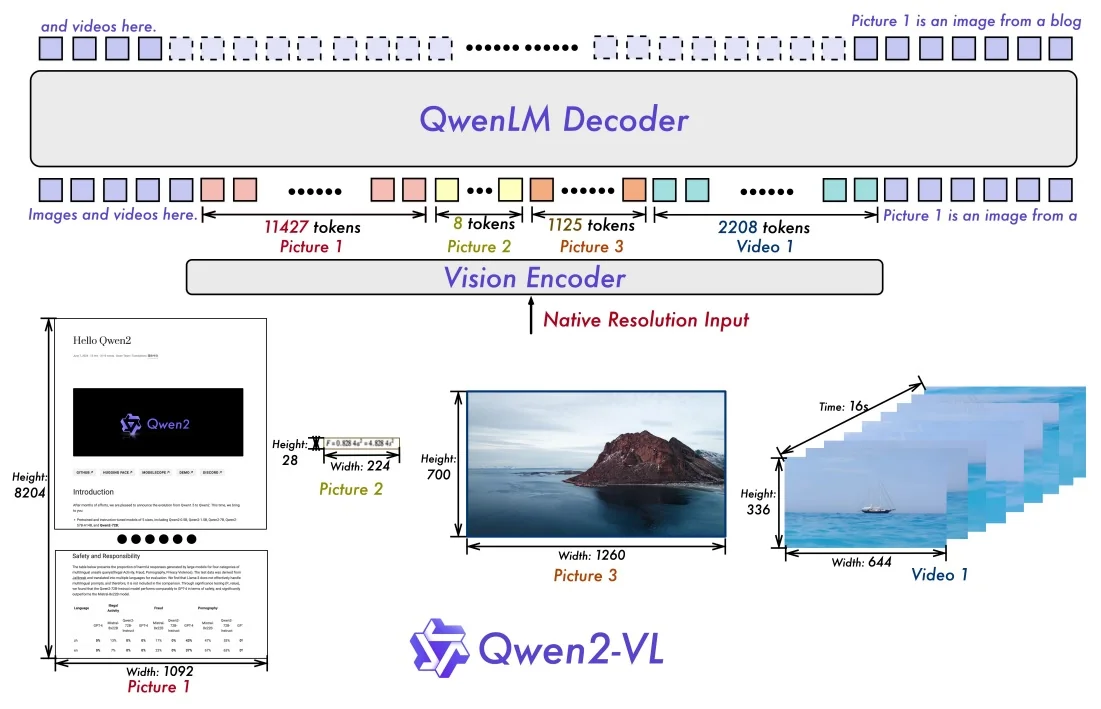

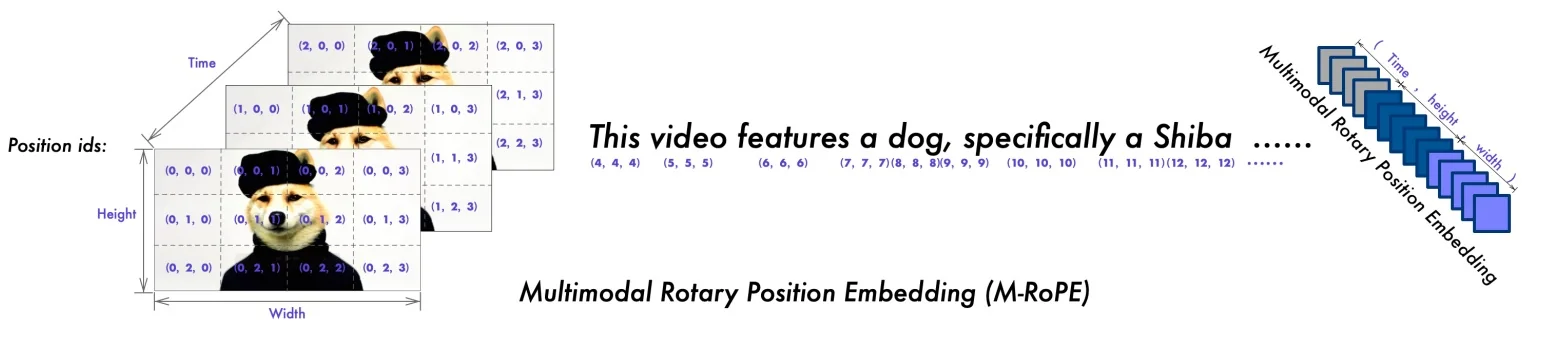

24.4.4 Transformers for Video Understanding

Transformers capture long-range spatio–temporal structure by self-attending over a sequence of tokens. For a clip \(\mathbf {X}\!\in \!\mathbb {R}^{T\times H\times W\times C}\), the video volume is first mapped to \(N\) tokens \(\{z_i\}_{i=1}^N\), then multi-head self-attention (MHSA) relates tokens across space and time [42, 16, 446, 151, 344]. Two core design choices govern effectiveness and efficiency: how to tokenize the video, and how to structure attention so compute and memory remain tractable.

What is a token in video Video tokens are compact spatiotemporal units, not raw pixels:

- Per-frame patches: Split each frame into \(P{\times }P\) patches; the sequence length is \(N=T\cdot \frac {HW}{P^2}\) [16].

- Tubelets (3D patches): Split the video into cuboids of size \(P_t{\times }P{\times }P\), reducing \(N\) by \(\approx P_t\) and embedding short-term motion at input [16, 42].

- CNN feature tokens: Use a 2D CNN per frame and treat spatial feature-map locations as tokens, leveraging ImageNet pretraining and curbing \(N\) [446].

Tokens are linearly projected to \(\mathbb {R}^d\) and enriched with space–time positional information (absolute or relative).

Attention over space and time Full joint attention over all \(N\) tokens costs \(O(N^2)\); with per-frame patches \(N=n_t n_h n_w\) grows multiplicatively in frames \(n_t\) and spatial grid \(n_h\times n_w\) (\(n_h=H/P\), \(n_w=W/P\)). For \(T{=}32\), \(H{=}W{=}224\), \(P{=}16\), we obtain \(N=6272\) and \(\sim 39\)M pairwise interactions per layer per head. To scale, modern designs either factorize attention or pool tokens:

- Divided space–time attention (TimeSformer): Perform spatial attention within each frame, then temporal attention across frames at corresponding spatial sites, reducing cost from \(O((n_t n_h n_w)^2)\) to \(O\!\big (n_t(n_h n_w)^2 + n_h n_w\,n_t^2\big )\) with strong accuracy [42].

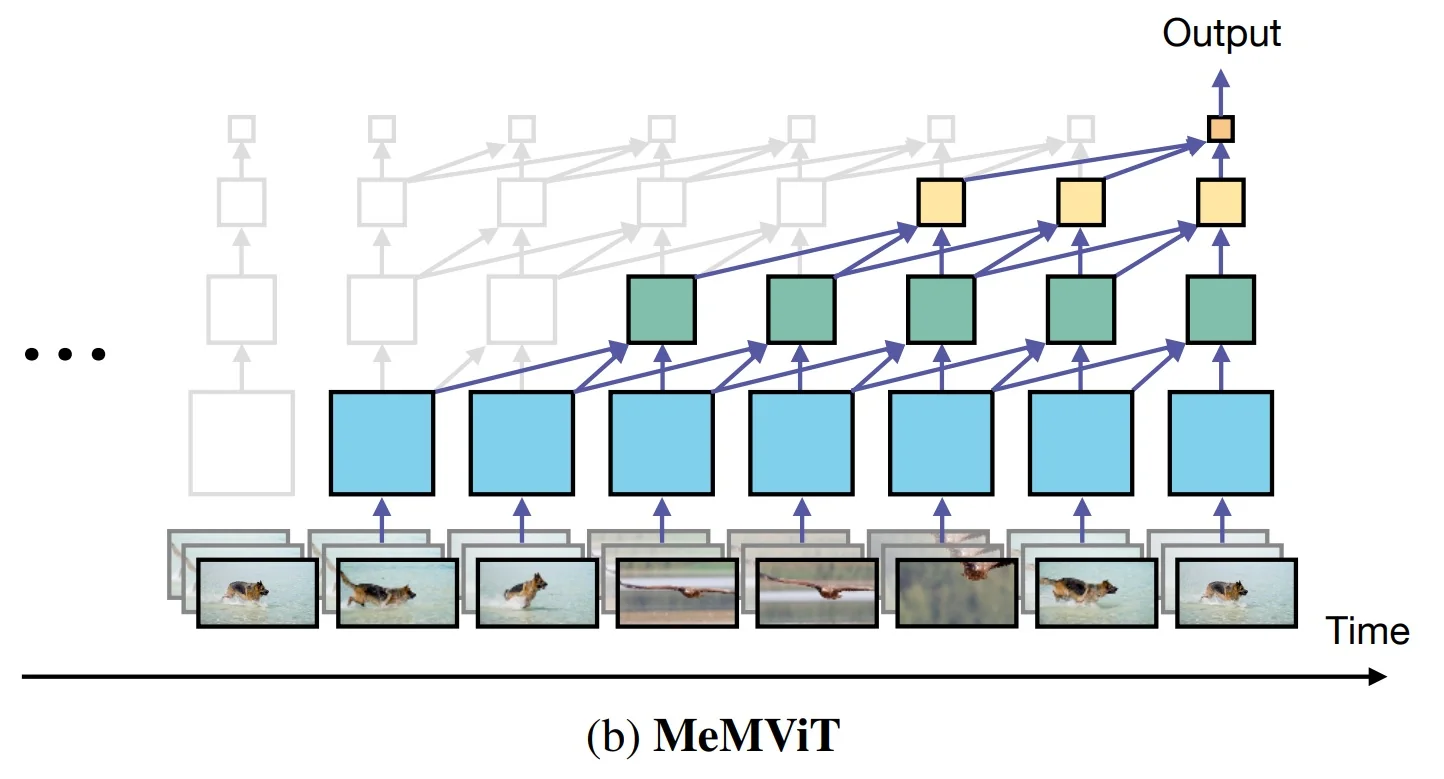

- Multiscale transformers (MViT/MViT-v2): Progressively pool tokens in space/time while widening channels, so deeper layers attend over fewer tokens; pooling attention with relative position biases yields excellent accuracy–efficiency trade-offs [151, 344].

- CNN–Transformer hybrids (VTN): Adopt a 2D CNN stem for spatial encoding and use temporal-only transformers on top, exploiting image pretraining and avoiding token explosion [446].

ViViT in depth: tokenization, factorization, computation, and findings ViViT [16] provides a clear blueprint for video transformers, isolating tokenization and attention structure as independent axes.

Tokenization ViViT studies (i) Per-frame patches with uniform frame sampling (\(N=n_t n_h n_w\)) and (ii) Tubelet embedding into \(P_t{\times }P{\times }P\) cuboids (\(N=\lfloor T/P_t\rfloor n_h n_w\)). Tubelets reduce \(N\) linearly in \(P_t\) and inject a motion prior. Initialization matters: inflating 2D patch projections (replicate across \(P_t\) and scale) or central-frame initialization stabilizes training, echoing I3D’s weight inflation.

What “spatial” and “temporal” transformers mean In ViViT’s factorized designs, attention neighborhoods are restricted:

- A Spatial transformer attends within frames to learn objects and layouts; frames can be processed in parallel.

- A Temporal transformer attends across frames at aligned spatial sites (or on frame-level summaries) to learn motion and ordering.

These are standard ViT blocks (MHSA+MLP+residuals); only the token grouping changes.

Architectural variants and compute ViViT compares four designs that trade expressivity for efficiency by constraining who attends to whom. With per-frame patches \(N=n_t n_h n_w\) (\(n_t\) frames, \(n_h{\times }n_w\) patches per frame), joint attention costs \(O(N^2)\); factorized variants decompose this into spatial and temporal parts while preserving the standard Transformer block (MHSA\(\rightarrow \)MLP with residuals and normalization).

- 1.

- Joint spatiotemporal attention: All tokens attend to all others across space and time; maximally expressive but \(O(N^2)\), practical only for short clips or coarse patching.

- 2.

- Factorized encoder: Spatial-only transformers process each frame to produce frame embeddings, then a temporal-only transformer aggregates across frames; \(\approx O\!\big (n_t(n_h n_w)^2\big ) + O\!\big (n_h n_w\,n_t^2\big )\) and spatial stages parallelize over frames.

- 3.

- Factorized self-attention: Within each block, apply spatial attention (within-frame) then temporal attention (across-frame at aligned sites); similar complexity to the factorized encoder with different information flow and regularization.

- 4.

- Factorized dot-product attention: Split attention heads into spatial-only and temporal-only inside a joint block, keeping parameter count while shrinking effective neighborhoods and compute.

With tubelets, \(n_t \leftarrow \lfloor T/P_t \rfloor \), so the temporal term \(O(n_h n_w\,n_t^2)\) becomes \(O\!\big (n_h n_w\,(T/P_t)^2\big )\), explaining why modest \(P_t\) yields substantial savings without sacrificing short-range motion cues.

Positioning relative to contemporaries

- TimeSformer [42]: Also factorizes space–time within blocks; ViViT broadens the design space (encoder- vs. block-level factorization, tubelets, initialization) and clarifies trade-offs.

- MViT/MViT-v2 [151, 344]: Add hierarchical token pooling and pooling attention with relative biases for strong accuracy–efficiency; ViViT serves as a transparent baseline isolating tokenization and factorization without a pyramid.

- VTN [446]: Uses a 2D CNN spatial stem with temporal transformers to curb tokens and leverage image pretraining; ViViT shows pure-transformer backbones can compete when tokenization and factorization are well chosen.

Practical guidance and empirical takeaways from ViViT ViViT’s systematic study suggests clear design choices for building effective and efficient video transformers:

- Prefer tubelets: Use modest temporal extent \(P_t\!\in \![2,4]\) to cut tokens, reduce FLOPs, and inject local motion cues. Tubelets generally outperform per-frame patches at matched compute.

- Adopt factorization for scale: Factorized encoders or block-level space–then–time attention retain most of joint attention’s accuracy while allowing longer clips and higher spatial resolution within a fixed budget.

- Encode space–time position: Apply factorized absolute or relative positional signals.

- Leverage large pretraining: Large-scale image pretraining (e.g., ImageNet-21K/JFT) is essential, since training pure video transformers from scratch on modest video datasets underperforms.

- Fewer multi-view passes needed: Efficient factorization makes it possible to process longer clips in a single forward pass, reducing reliance on expensive multi-view testing.

Why transformers for video Transformers provide a global spatiotemporal receptive field in a single layer via content-based self-attention, allowing direct connections between distant events without the deep local stacking of 3D CNNs or the sequential bottlenecks of RNNs. While naive all-to-all attention over \(N\) video tokens costs \(O(N^2)\), practical video transformers curb both \(N\) and the attention neighborhoods through tokenization into tubelets (reducing sequence length and injecting short-range motion cues), attention factorization (space-then-time or encoder-level separation), and multiscale pooling (progressively merging tokens while widening channels), achieving long-range reasoning at tractable compute [42, 16, 151, 344, 446]. The result is a backbone that preserves temporal reasoning capacity while scaling to longer clips and higher resolutions within realistic budgets.

24.4.5 Visualizing and Localizing Actions

Visualizing Video Models

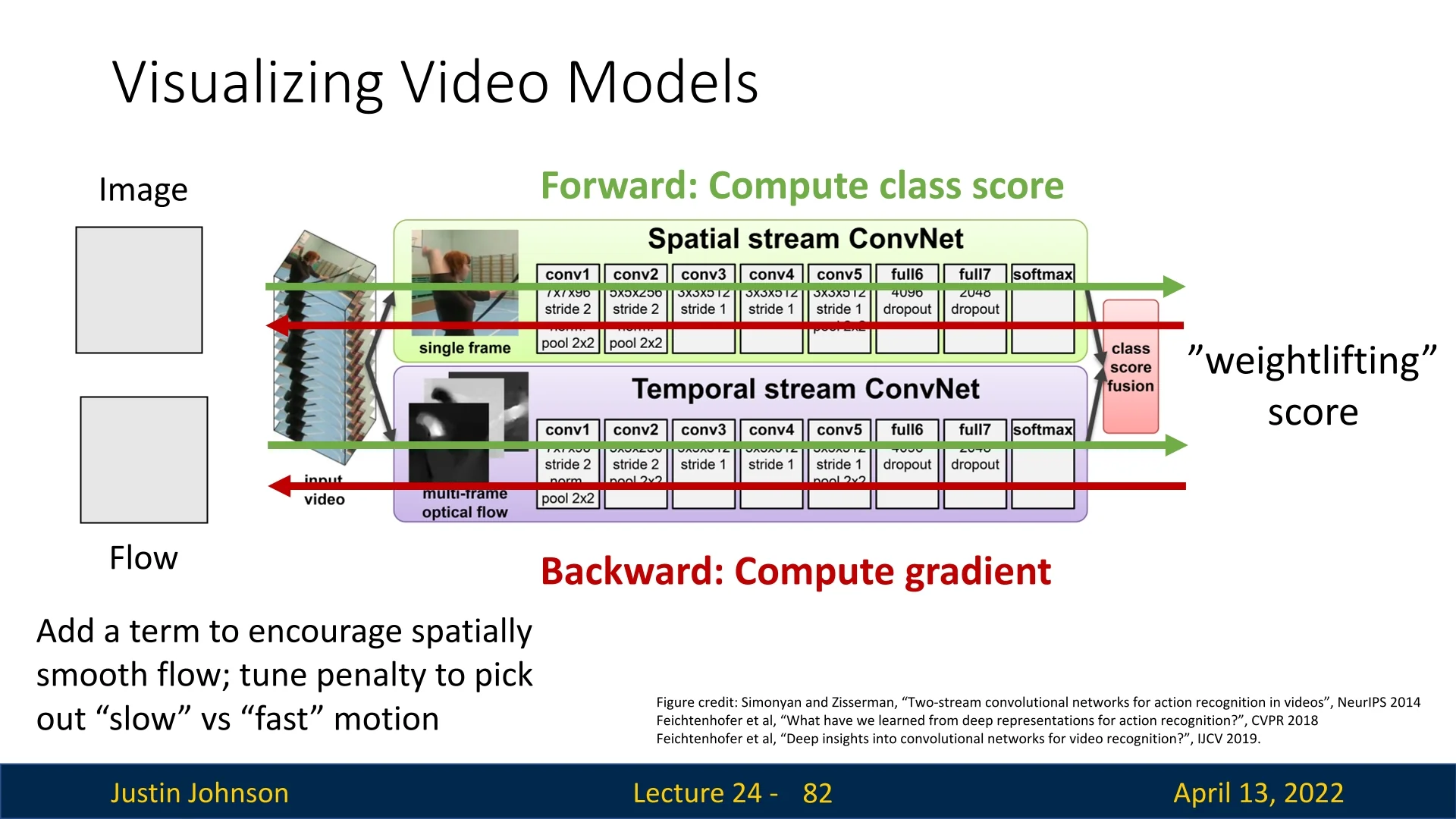

A useful way to probe what a trained video classifier has learned is to optimize a synthetic video \(\mathbf {V}\!\in \!\mathbb {R}^{C\times T\times H\times W}\) to maximize a class score \(S_c(\mathbf {V})\) while adding priors that favor naturalistic solutions [154, 156]. A generic objective is \begin {equation} \label {eq:chapter24_vis_objective} \max _{\mathbf {V}} \; S_c(\mathbf {V}) \;-\; \lambda _s \,\mathcal {R}_{\mbox{space}}(\mathbf {V}) \;-\; \lambda _t \,\mathcal {R}_{\mbox{time}}(\mathbf {V}), \end {equation} where \(\mathcal {R}_{\mbox{space}}\) encourages spatial smoothness (e.g., spatial total variation) and \(\mathcal {R}_{\mbox{time}}\) encourages temporal coherence (e.g., penalties on finite differences across adjacent frames). By tuning the temporal penalty \(\lambda _t\), one can bias the optimized video toward slow motion (large \(\lambda _t\) suppresses rapid frame-to-frame changes) or fast motion (small \(\lambda _t\) allows rapid changes). This separates appearance cues (what) from motion regimes (how fast), revealing complementary evidence the model uses.

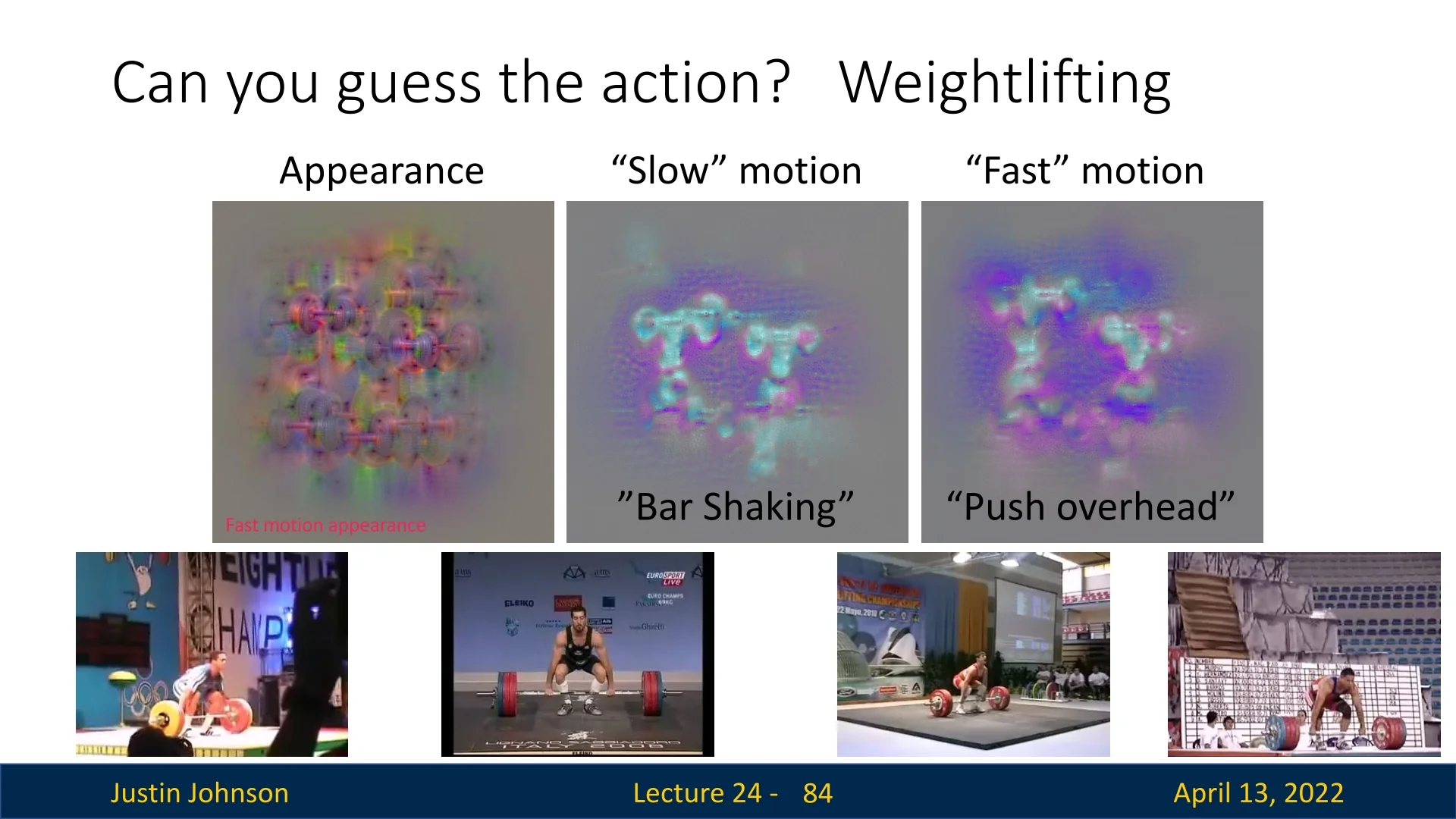

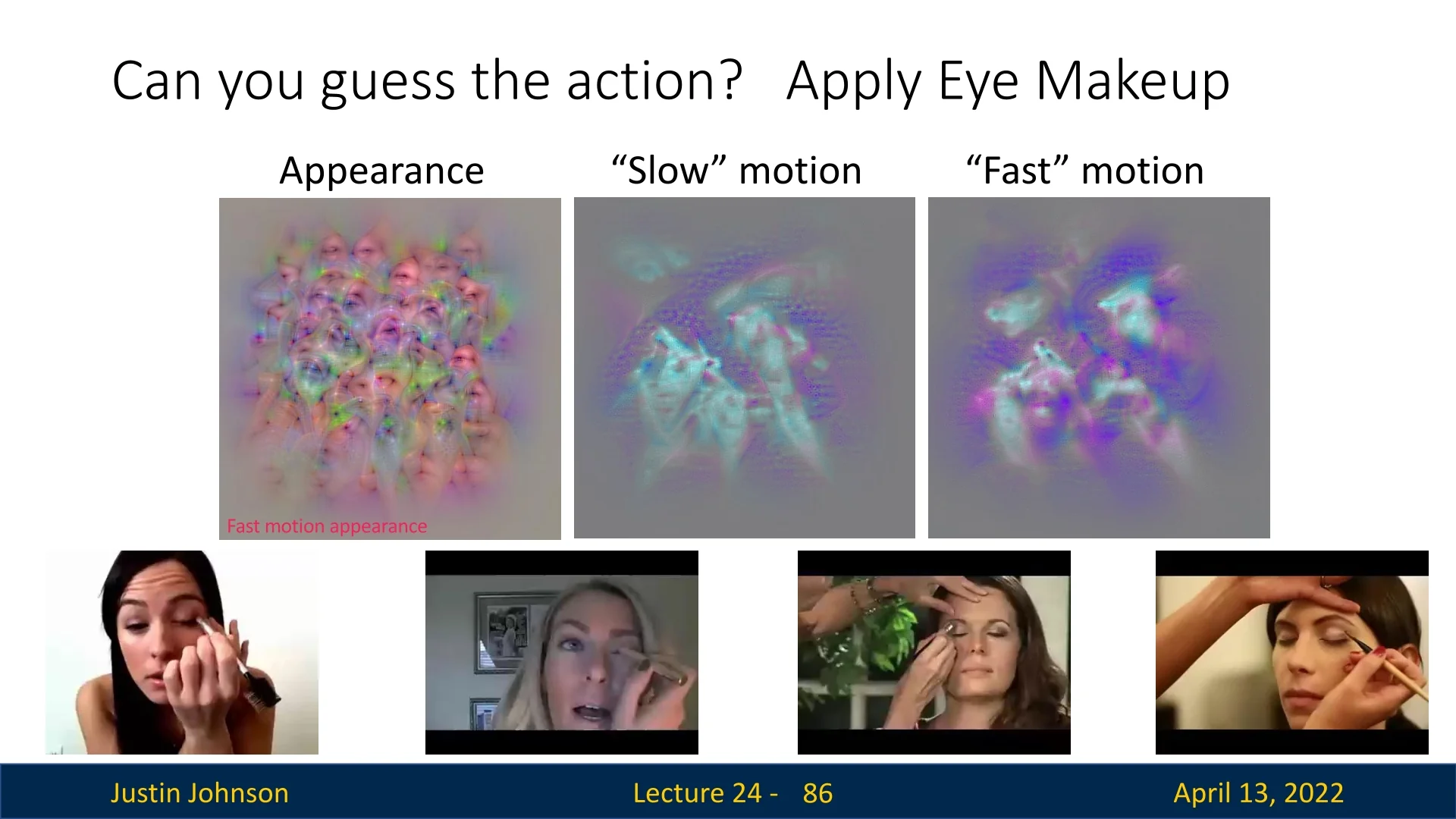

Qualitative examples Optimizing (24.10) for specific classes yields intuitive decompositions into appearance, slow motion, and fast motion channels:

- Weightlifting: The appearance channel emphasizes the barbell and lifter; the slow component accentuates bar shaking; the fast component emphasizes the push overhead—together aligning with the weightlifting concept.

- Apply eye makeup: The appearance channel contains many faces (consistent with makeup tutorials); the slow component captures deliberate hand movements; the fast component highlights brushing strokes.

Temporal Action Localization

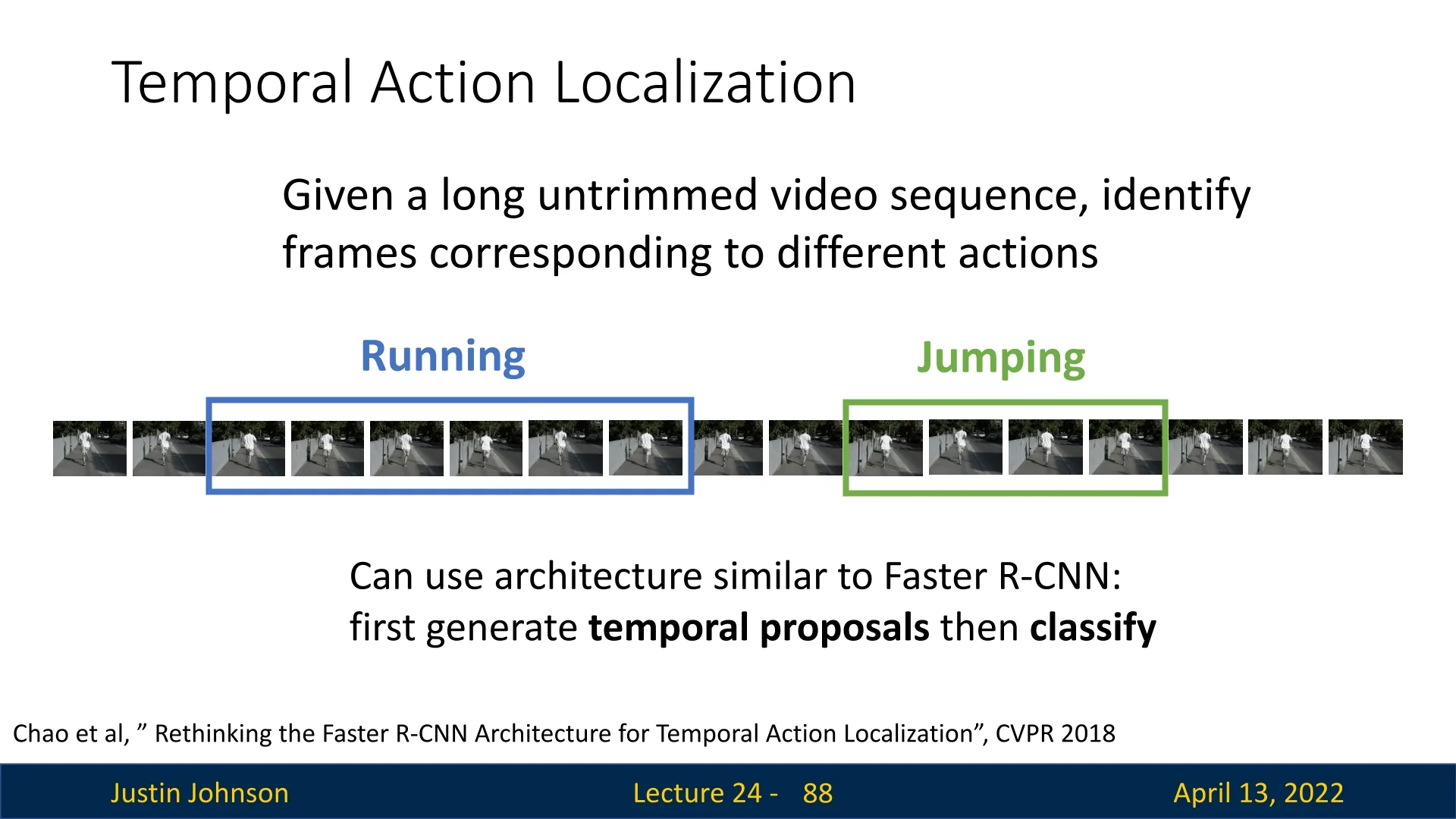

Problem: Given an untrimmed video, identify the temporal extents of actions and their labels. A popular approach mirrors object detection: first generate temporal proposals, then classify and refine them [78]. Modern systems use 1D temporal anchors or boundary-matching modules coupled with clip-level features from 2D/3D backbones.

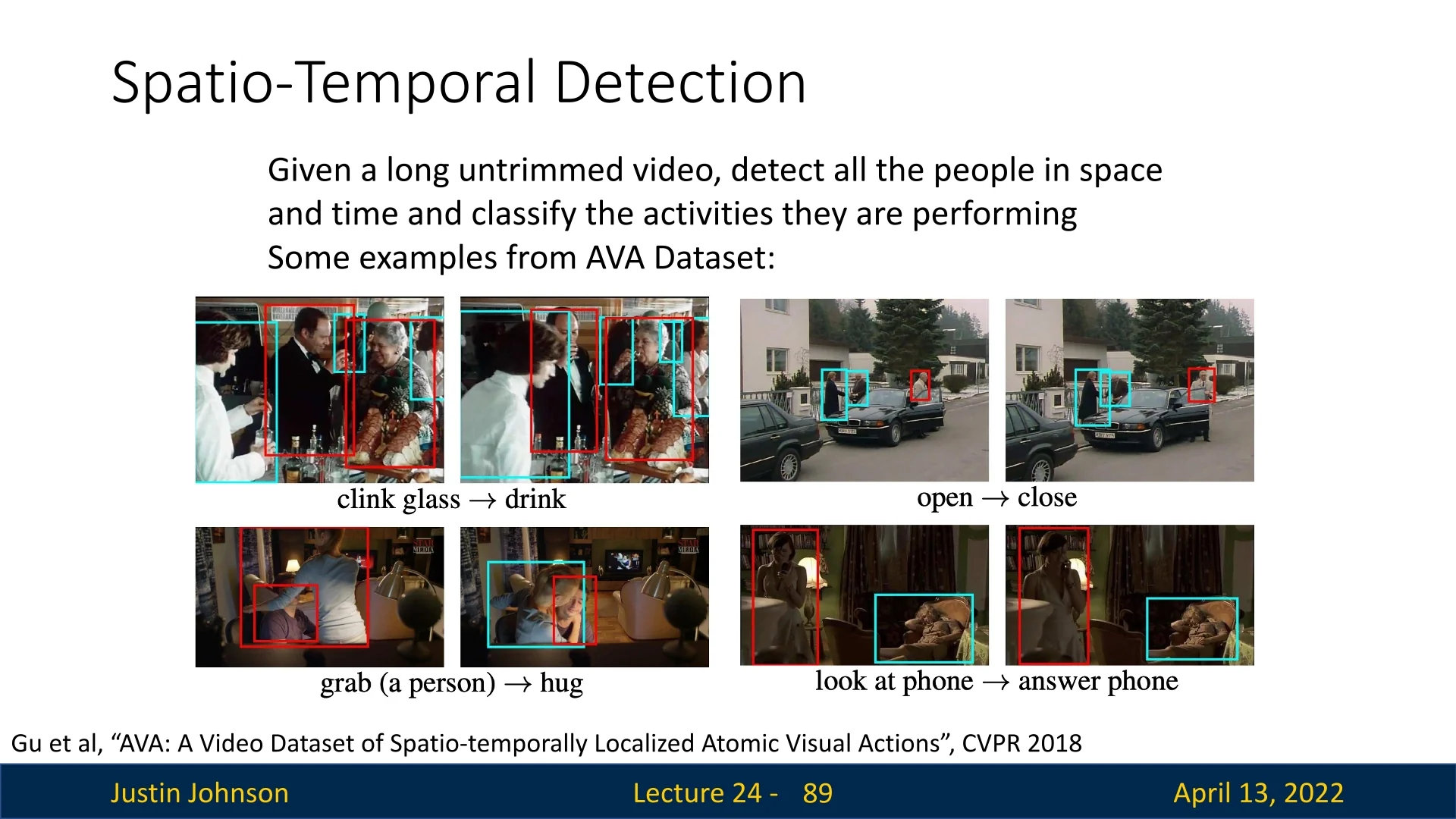

Spatio-Temporal Action Detection

Problem: Detect who does what in space and time: localize people with bounding boxes across frames (tubes) and assign action labels. The AVA dataset provides dense, frame-level annotations of atomic visual actions for people in 15-minute movie clips, enabling research on fine-grained spatiotemporal detection and interaction understanding [191]. Models typically combine per-frame person detection, tube linking, and action classification with temporal context.

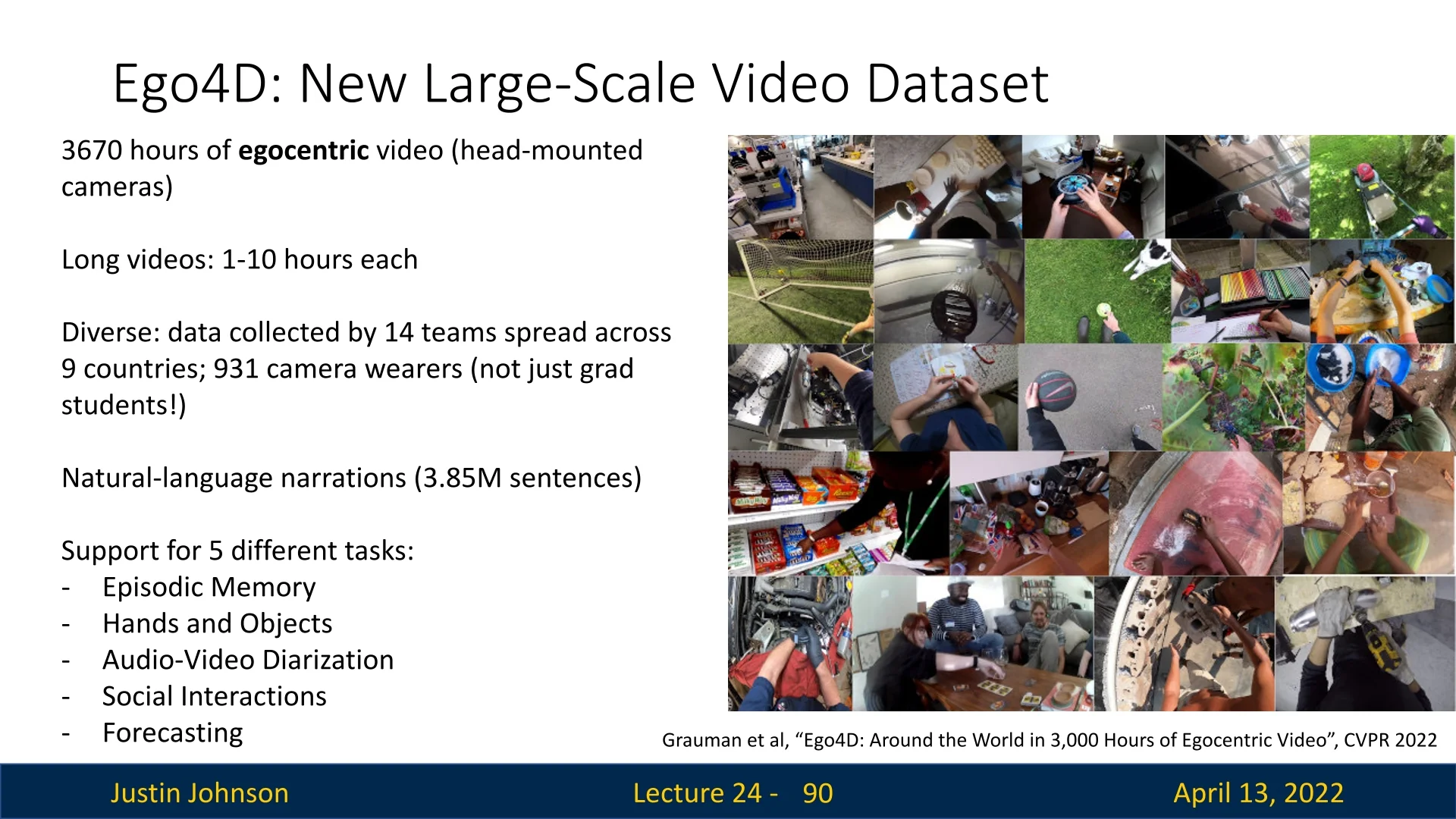

Ego4D: Large-Scale Egocentric Video

Ego4D is a comprehensive egocentric benchmark comprising 3,670 hours of head-mounted, real-world video collected by 14 teams across 9 countries from 931 camera wearers [186]. Videos are long (1–10 hours each) and accompanied by 3.85M natural language narrations. The dataset supports five task families:

- Episodic memory: Retrieve or localize past events based on queries.

- Hands and objects: Detect and track hands and manipulated objects from a first-person perspective.

- Audio–video diarization: Segment and attribute audio–visual events to speakers and sources.

- Social interactions: Recognize and characterize interpersonal behaviors.

- Forecasting: Anticipate future activities or states from ongoing observations.

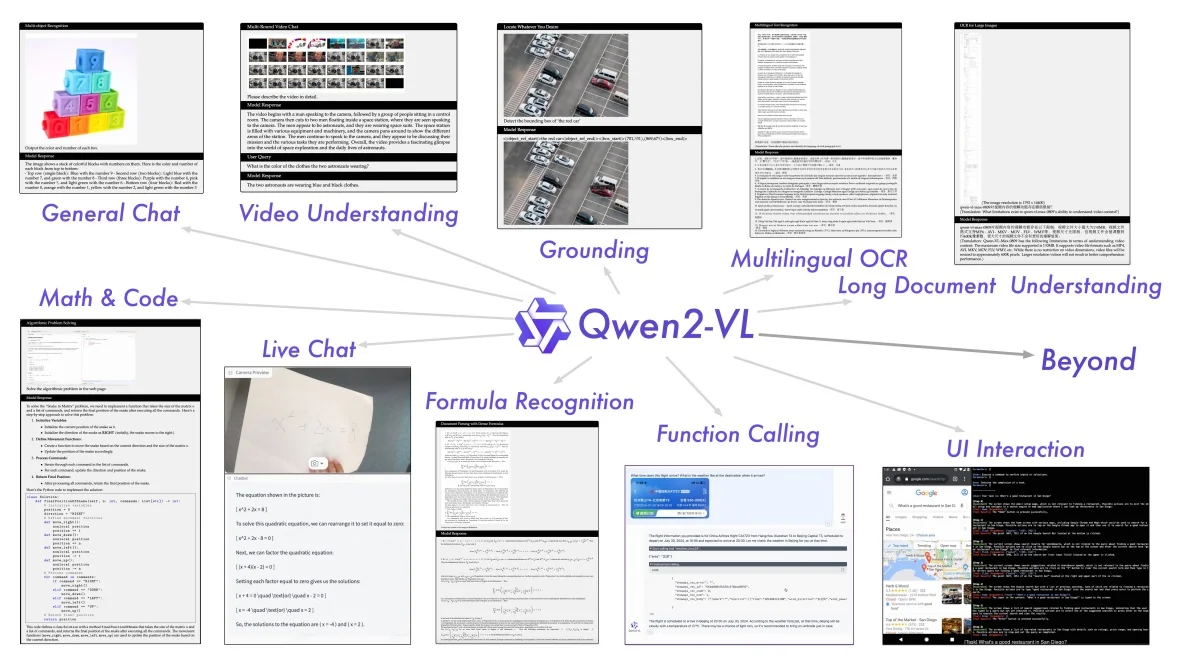

Enrichment 24.5: Vision–Language Alignment Precursors

The first step toward video–language models was learning how to connect vision and language at scale. As detailed in Section §22, CLIP demonstrated how contrastive alignment could map visual features into a shared language space. Building on this foundation, SigLIP and the BLIP family established the now-standard connector paradigm for mapping visual encoders into LLM-friendly representations. This section focuses on the key image–language precursors that underpin later video systems: SigLIP for improved contrastive alignment, BLIP and BLIP-2 for lightweight vision–LLM bridging, and SigLIP 2 as a stronger, multilingual and dense-capable successor.

Enrichment 24.5.1: SigLIP: Contrastive Alignment with Sigmoid Loss

From CLIP to SigLIP (Intuition First) CLIP learns with a batch–softmax game: in each row/column of the similarity matrix, the true pair must beat all in-batch negatives. This global competition is powerful, but it ties learning quality to batch composition (you need many, diverse negatives), forces expensive all–gathers across devices, and becomes fragile with small or imbalanced batches.

SigLIP [758] changes the game: instead of “one-vs-many” races, it asks a simple yes/no question for each image–text pair—“do they match?”—and trains with a pairwise sigmoid (logistic) loss. By turning alignment into many independent binary decisions, SigLIP:

- Decouples supervision from batch size (every off-diagonal pair is a labeled negative, no global normalization needed),

- Stabilizes gradients (no row/column softmax where a few hard negatives dominate),

- Improves calibration (scores behave like probabilities rather than “who won the batch”),

- Cuts memory & comms (no all–gathers to normalize across the full batch).

Algorithmic Formulation and Intuition With \(n\) image embeddings \(x_i\) and text embeddings \(y_j\) (both L2-normalized), CLIP builds \(S_{ij}{=}x_i^\top y_j\) and optimizes two batch–softmax losses (image\(\!\to \!\)text and text\(\!\to \!\)image): \[ \mathcal {L}_{\mbox{CLIP}} =\frac {1}{2}\!\left [ \frac {1}{n}\sum _{i=1}^{n}\!-\log \frac {\exp (\tau S_{ii})}{\sum _{j=1}^{n}\exp (\tau S_{ij})} + \frac {1}{n}\sum _{j=1}^{n}\!-\log \frac {\exp (\tau S_{jj})}{\sum _{i=1}^{n}\exp (\tau S_{ij})} \right ], \] where the learned temperature \(\tau \) sharpens the softmax; each positive must outrank all \(n{-}1\) negatives in its row/column.

SigLIP replaces this global competition with a per-pair logistic objective: \begin {equation} \label {eq:chapter24_siglip_loss} \mathcal {L}_{\mbox{SigLIP}} = -\frac {1}{n}\sum _{i=1}^{n}\sum _{j=1}^{n} \log \sigma \!\big (z_{ij}\cdot (t\,x_i^\top y_j + b)\big ), \end {equation} with labels \(z_{ij}{=}1\) for matches (\(i{=}j\)) and \(-1\) otherwise (non-match). The formulation introduces two additional learnable scalars:

- Temperature \(t=\exp (t')\). Instead of learning \(t\) directly, the model learns an unconstrained parameter \(t'\), which is exponentiated to ensure \(t>0\). This acts as a similarity sharpness knob: larger \(t\) magnifies dot products, steepening the logistic curve and pushing probabilities closer to \(0\) or \(1\); smaller \(t\) smooths the curve, reducing overconfidence. Exponentiation guarantees stability while allowing flexible scaling during training.

- Bias \(b\). A learnable offset that shifts the decision boundary of the sigmoid. It helps correct for the extreme class imbalance of the loss: each minibatch has only \(n\) positives but \(n^2-n\) negatives. Without \(b\), the logits for negatives can dominate early optimization, leading to vanishing gradients for positives.

Reading the terms in context:

- \(x_i^\top y_j\): cosine-like similarity between L2-normalized embeddings.

- \(t=\exp (t')\): positive temperature that scales similarities, controlling how confidently pairs are classified.

- \(b\): bias that shifts the sigmoid’s threshold, stabilizing optimization when negatives vastly outnumber positives.

- \(z_{ij}\in \{+1,-1\}\): binary label, turning alignment into independent logistic decisions for each pair—no competition across rows/columns as in CLIP.

CLIP vs. SigLIP—why it matters

- Normalization target. CLIP normalizes within each row/column via softmax (needs the whole batch); SigLIP applies a sigmoid per pair (no batchwise denominator).

- Negatives. CLIP’s signal hinges on the number/hardness of in-batch negatives; SigLIP gets explicit negatives from all off-diagonal pairs, even in modest batches.

- Gradient coupling. CLIP couples all pairs in a row/column (hard negatives can dominate); SigLIP yields decoupled per-pair gradients with lower variance.

- Calibration. CLIP scores reflect “winning the batch”; SigLIP’s probabilities are directly interpretable as match likelihoods.

- Distributed cost. CLIP typically needs global all–gathers; SigLIP can be computed in device-local tiles (see the below part on efficient computation).

# Sigmoid contrastive loss pseudocode (SigLIP)

# img_emb : image embeddings [n, d]

# txt_emb : text embeddings [n, d]

# t_prime, b : learnable temperature and bias

# n : batch size

t = exp(t_prime)

zimg = l2_normalize(img_emb)

ztxt = l2_normalize(txt_emb)

logits = dot(zimg, ztxt.T) * t + b

labels = 2 * eye(n) - ones(n) # +1 on diag (matches), -1 off-diag (non-matches)

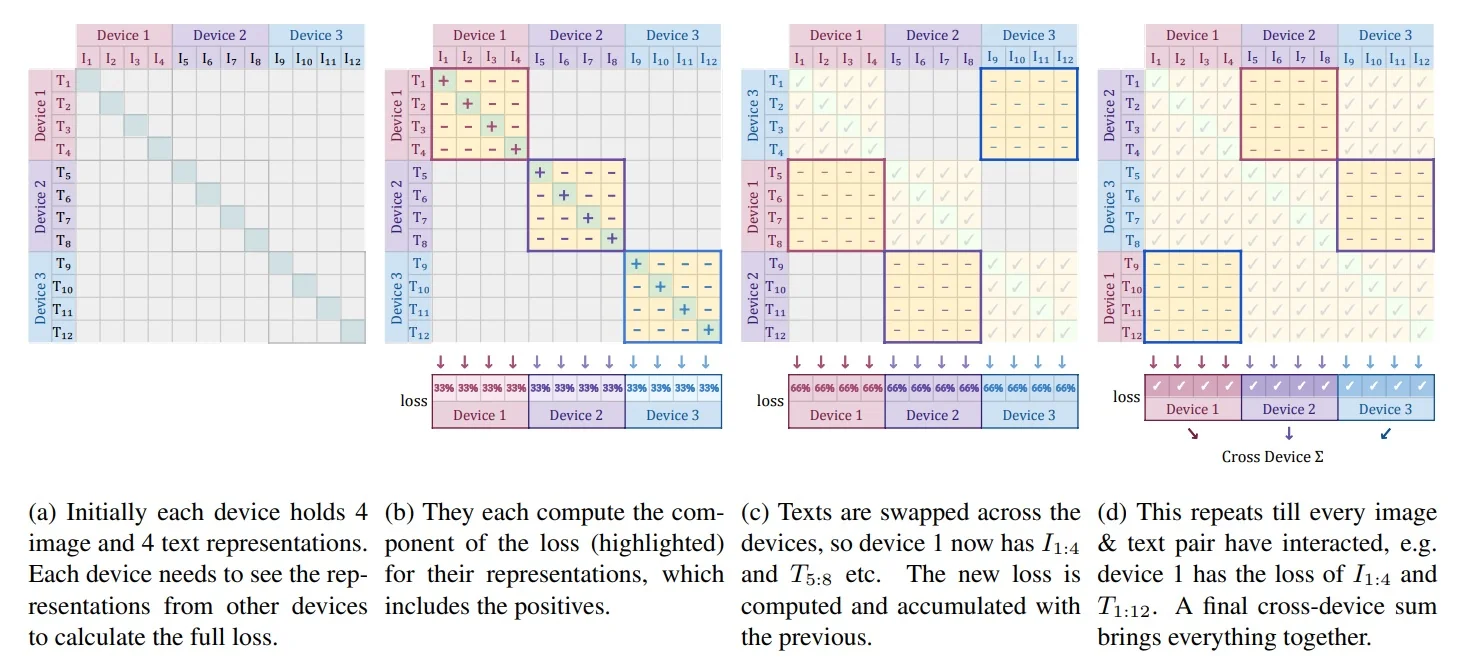

loss = -sum(log_sigmoid(labels * logits)) / nEfficient Implementation The pairwise objective also simplifies distributed training. CLIP’s softmax normalizes over the global batch and thus materializes an \(n{\times }n\) similarity matrix across devices via all-gathers. SigLIP computes the loss locally in chunked blocks, avoiding global normalization and keeping only device-resident tiles in memory. The footprint drops from \(O(n^2)\) to \(O(b^2)\), where \(b\) is the per-device batch size, enabling very large effective batches on comparatively few accelerators. The below figure illustrates the blockwise computation.

Empirical Comparison to CLIP: What Improves in Practice In realistic training settings (small–to–medium batches; noisy web data), SigLIP generally matches or surpasses CLIP while requiring less tuning. The improvements are explained by its pairwise design:

- Batch-size resilience. Because supervision is per pair, SigLIP does not need thousands of negatives per update. Performance scales smoothly up to moderate batch sizes and then plateaus, avoiding CLIP’s reliance on extreme global batches.

- Lower gradient variance. Without a row/column softmax, updates are not dominated by a few hard negatives, yielding smoother optimization and more stable convergence.

- More reliable confidence. Logistic outputs can be interpreted directly as “probability of match”. This leads to better-calibrated similarity scores, making confidence thresholds more trustworthy for retrieval, filtering, or dataset cleaning.

- Robustness to noise. In CLIP, mislabeled or loosely aligned pairs can distort the softmax normalization for a whole row/column. In SigLIP, such outliers only affect their own binary terms, containing the damage and improving robustness on noisy web corpora.

- Efficiency. Losses are computed locally on each device in small blocks, avoiding global all-gathers. This reduces memory and communication costs and makes very large effective batches feasible even on limited hardware.

Impact, Limitations, and Legacy Impact. SigLIP proved that large-scale vision–language alignment can be achieved without global softmax or massive negatives. Its simple, stable recipe made it the backbone for connector-style systems such as BLIP/BLIP-2 (where Q-Former bridges vision encoders to LLMs) and Video-LLMs (where temporal encoders extend SigLIP-style connectors to video).

Limitations. As a purely binary contrastive method, SigLIP:

- Judges only match vs. non-match, lacking multi-way semantics or compositional reasoning.

- Aligns globally but does not yield dense/localized features unless augmented.

- Cannot generate captions or reasoning without an attached LLM.

Legacy. Extensions such as SigLIP 2 [636] add multilingual training, masked prediction, and self-distillation for cross-lingual and localized tasks.

Enrichment 24.5.2: BLIP: Bootstrapping Language–Image Pretraining

High-Level Idea Most large-scale vision–language corpora are scraped from the web by pairing images with their surrounding alt-text—short strings originally written for accessibility or indexing. While attractive for scale, alt-text was never intended as faithful supervision. It is often:

- Missing, e.g. filenames like “IMG_123.jpg” with no descriptive text for the image in its alt text.

- Generic, e.g. “beautiful view” that offers little semantic grounding.

- Off-topic, e.g. boilerplate such as “click here to buy”.

When such noisy associations dominate, models risk learning shortcuts (e.g. linking logos directly to brand names) instead of genuine visual grounding. A second challenge is an objective gap: alt-text resembles retrieval labels more than natural captions or question-answer pairs. Training only with discriminative alignment (as in CLIP) yields strong retrieval but poor generation; training only with captions produces fluent language but weak grounding.

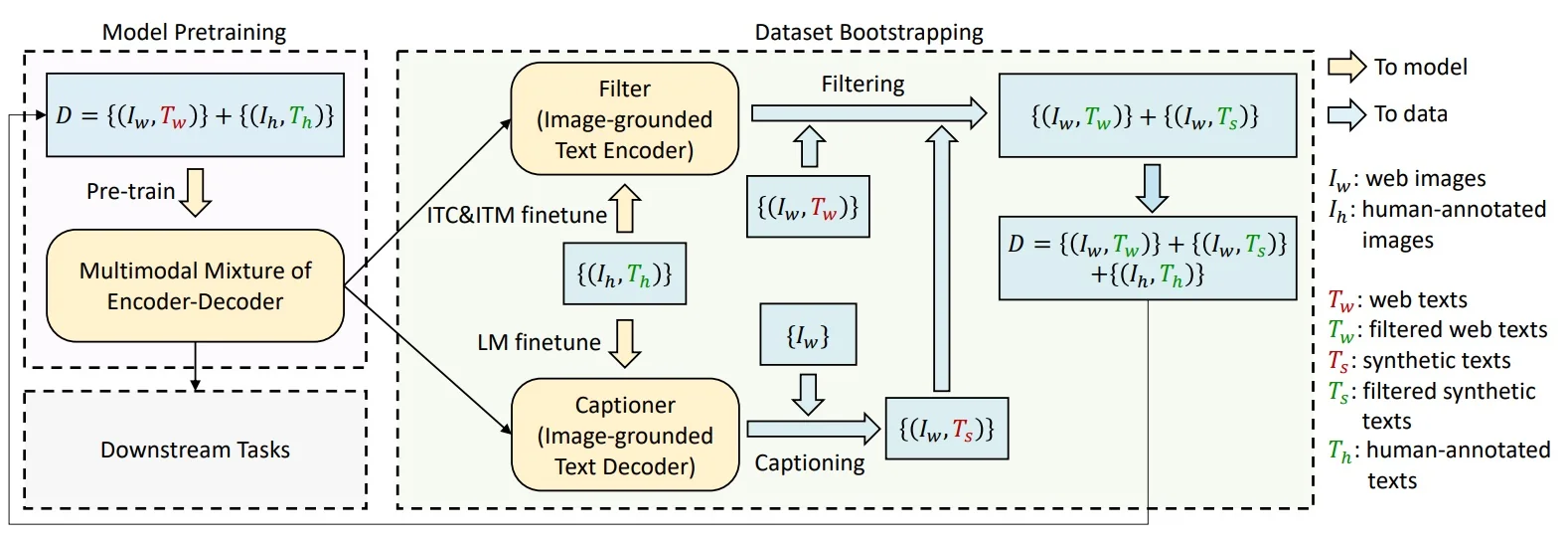

BLIP’s Two-Part Strategy The authors observe that these problems reinforce each other: noisy supervision destabilizes multi-task learning, and narrow objectives fail to transfer broadly. BLIP addresses both with a simple recipe: first curate the data, then train a unified model that can align, ground, and generate.

- Step 1 — Bootstrapping with CapFilt. Instead of trusting raw alt-text, BLIP trains its own Captioner and Filter on a small, clean human-annotated dataset. The Captioner (a generative decoder) produces synthetic captions grounded in visual content, while the Filter (a discriminative encoder) discards both weak alt-text and low-quality synthetic captions. This process rebuilds the large pretraining corpus “from within”, producing cleaner, semantically faithful supervision.

-

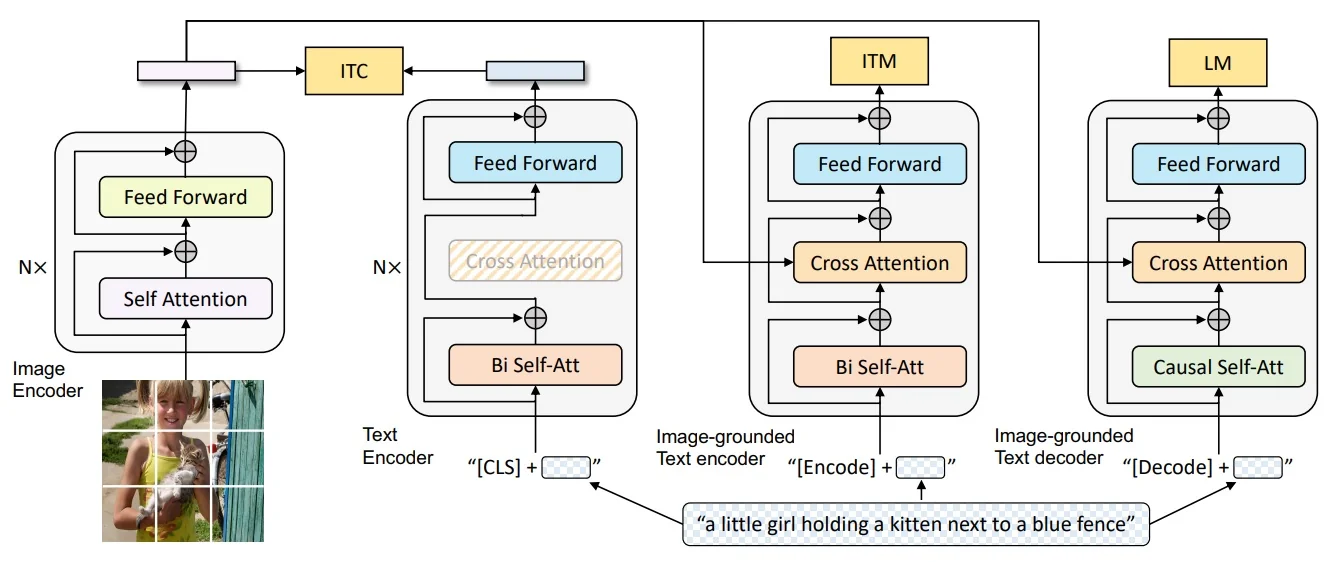

Step 2 — Unified encoder–decoder. BLIP introduces a Multimodal Encoder–Decoder (MED) that supports three complementary modes with largely shared parameters:

- Image–Text Contrastive (ITC). Aligns unimodal encoders for fast retrieval.

- Image–Text Matching (ITM). Uses cross-attention to check whether a caption truly matches an image.

- Language Modeling (LM). Uses a causal decoder to generate captions or answers, reusing the same cross-attention for stable fusion.

By combining these modes, BLIP avoids the trade-off between retrieval strength and generative ability, yielding a single checkpoint that can both discriminate and generate.

Intuition. By first cleaning the data, BLIP removes much of the noise that would otherwise destabilize multi-task optimization. This makes it feasible to train a single model on diverse objectives without one collapsing the others. At the same time, the unified architecture avoids the brittleness of task-specific designs: contrastive alignment alone cannot generate, and pure generation often ignores fine-grained grounding. Combining the two under one framework allows the model to tackle multiple problems at once—retrieval, discrimination, and generation—so that improvements in one skill reinforce the others, producing a more balanced and versatile vision–language learner.

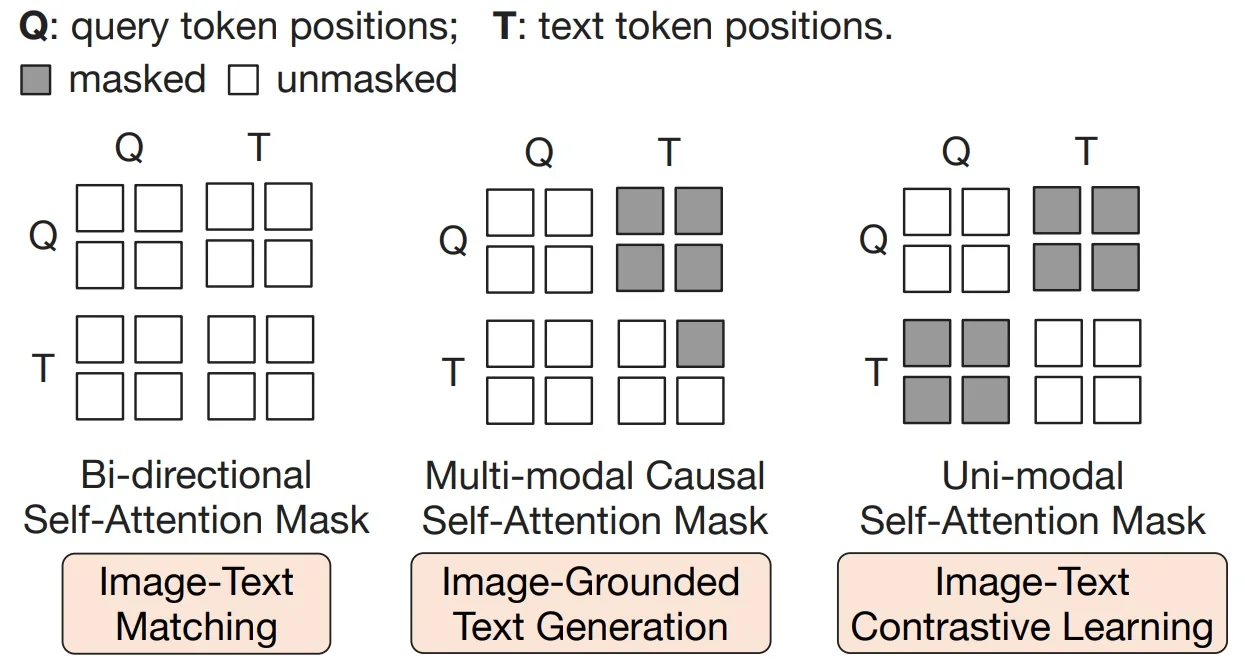

Method

Unified Architecture with Three Functional Modes Rather than building separate networks for retrieval, grounding, and captioning, BLIP uses a single multimodal encoder–decoder backbone that can be run in three different configurations. Most of the heavy components—the vision encoder, cross-attention layers, and feed-forward blocks—are shared across all modes. What changes between them is how attention is applied and which inputs are activated:

- In contrastive alignment, image and text streams run separately without cross-attention.

- In matching, the text stream is augmented with cross-attention over image tokens.

- In generation, the decoder uses causal (masked) self-attention but reuses the same cross-attention and feed-forward layers as the encoder.

This parameter sharing means that improvements in one objective (e.g., better grounding in ITM) flow into the others, stabilizing training and avoiding the need to maintain multiple specialized checkpoints.

- 1.

- Image–Text Contrastive (ITC). The unimodal image encoder and text encoder produce global embeddings. A contrastive loss aligns paired embeddings while pushing apart mismatched ones, giving BLIP strong retrieval and zero-shot transfer.

- 2.

- Image–Text Matching (ITM). The text encoder is extended with cross-attention layers that attend to image features. The model then predicts whether a caption truly matches its paired image. Hard negatives are sampled from ITC to make the discrimination sharper.

- 3.

- Language Modeling (LM). The decoder reuses the same cross-attention and feed-forward blocks as the encoder, but changes the style of self-attention. In the encoder, self-attention is bidirectional: each token can attend to all others, both before and after it, which is ideal for understanding a complete sentence. In contrast, the LM decoder uses causal masking: each token can only attend to those that came earlier in the sequence, never to future tokens. This forces the model to generate text one word at a time, predicting the next token given the history. By combining causal self-attention with cross-attention to the image features, BLIP can produce grounded captions and answers in an autoregressive way, rather than simply classifying pairs.

Why Causal vs. Bidirectional Attention?

- Bidirectional self-attention (ITC, ITM). For understanding tasks, the text stream should read a sentence holistically: each token attends to all others (past and future) to form a context-rich representation. This is ideal for global alignment (ITC) and fine-grained verification (ITM), where the model must judge a complete image–text pair.

- Causal (masked) self-attention (LM). For generation, the decoder must predict the next token given only the prefix; allowing access to future tokens would let it “peek” and trivially copy the target. Causal masking enforces autoregressive decoding and yields fluent, grammatical captions that remain conditioned on the image via cross-attention.

Example. In retrieval or matching, the phrase “a dog on the grass” is compared to an image as a whole—bidirectional attention fits. In captioning, the model writes “A dog is running …” one token at a time—causal masking prevents cheating and maintains coherence.

Objectives in Mathematical Form. BLIP optimizes three complementary losses within the shared backbone:

- Image–Text Contrastive (ITC). For paired embeddings \((v_i, t_i)\) and negatives \((v_i, t_j)\), BLIP applies a symmetric InfoNCE loss: \[ \mathcal {L}_{\mathrm {ITC}} = -\frac {1}{N} \sum _{i=1}^N \Big [ \log \frac {\exp (\mathrm {sim}(v_i,t_i)/\tau )}{\sum _{j=1}^N \exp (\mathrm {sim}(v_i,t_j)/\tau )} + \log \frac {\exp (\mathrm {sim}(t_i,v_i)/\tau )}{\sum _{j=1}^N \exp (\mathrm {sim}(t_i,v_j)/\tau )} \Big ], \] where \(\mathrm {sim}\) is cosine similarity and \(\tau \) a temperature. Intuition: Encourages globally aligned representations so retrieval works out of the box.

- Image–Text Matching (ITM). With image tokens \(v\) and text tokens \(t\), the cross-attentive encoder predicts a binary label \(y \in \{0,1\}\): \[ \mathcal {L}_{\mathrm {ITM}} = - \big [ y \log p(y{=}1|v,t) + (1-y)\log p(y{=}0|v,t) \big ]. \] Intuition: Forces the model to judge whether an entire caption matches an image, sharpening grounding beyond coarse similarity.

- Language Modeling (LM). For a target sequence \(t = (t_1,\ldots ,t_L)\) and image \(v\), the decoder with causal masking maximizes \[ \mathcal {L}_{\mathrm {LM}} = - \sum _{k=1}^L \log p(t_k \mid t_{<k}, v). \] Intuition: Enforces left-to-right text generation conditioned on image features, producing fluent grounded captions.

Together, these objectives form a joint training signal: ITC aligns global spaces, ITM enforces pairwise discrimination, and LM teaches autoregressive generation. Their complementarity stabilizes multi-task learning within one backbone.

Training Framework: End-to-End Chronology (CapFilt \(\rightarrow \) Final BLIP) Web alt-text is often underspecified or off-topic, which destabilizes pretraining. BLIP therefore separates data construction from final model training in a chronological, three-phase pipeline: (1) train specialized tools, (2) rebuild the dataset, (3) train the final unified model.

- 1.

- Phase 1: Forge the tools on clean data.

- Captioner (generative proposal). Start from a BLIP initialization and fine-tune the image-grounded decoder in LM mode on a small human-annotated set (e.g., COCO). This produces a model that can generate descriptive, image-relevant synthetic captions for web images. Stochastic decoding (e.g., nucleus sampling) increases diversity and coverage.

- Filter (discriminative selection). Independently fine-tune another BLIP initialization in ITM (binary match) with ITC-guided hard negatives on the same clean set. This yields an image–text verifier that can score the semantic fidelity of any pair. Decoupling Captioner and Filter avoids confirmation bias (a generator endorsing its own outputs).

- 2.

- Phase 2: Rebuild the large-scale corpus (CapFilt).

- Generate. Run the Captioner over the web image pool \(\{I_w\}\) to produce synthetic texts \(\{T_s\}\).

- Select. Run the Filter on both sources—the original web texts \(\{T_w\}\) and synthetic texts \(\{T_s\}\)—to keep only high-quality pairs: \[ \{(I_w, T'_w)\} = \mathrm {Filter}\big (\{(I_w, T_w)\}\big ), \qquad \{(I_w, T'_s)\} = \mathrm {Filter}\big (\{(I_w, T_s)\}\big ). \]

- Assemble. Form the bootstrapped pretraining set \[ \mathcal {D}_{\mathrm {boot}} \;=\; \underbrace {\{(I_h, T_h)\}}_{\mbox{human-annotated}} \;\cup \; \underbrace {\{(I_w, T'_w)\}}_{\mbox{filtered web}} \;\cup \; \underbrace {\{(I_w, T'_s)\}}_{\mbox{filtered synthetic}}. \] Here \(T'_w\) and \(T'_s\) denote pairs the Filter judged as matched; images with no good text are dropped.

- 3.

- Phase 3: Train the final unified BLIP on \(\mathcal {D}_{\mathrm {boot}}\).

-

A new BLIP model is initialized and optimized on all three objectives concurrently. In practice, each minibatch is sampled from the same purified dataset \(\mathcal {D}_{\mathrm {boot}}\), and the model routes the inputs through different attention masks and heads depending on the objective:

- ITC (unimodal encoders; no cross-attention) — learns global alignment by comparing embeddings of paired vs. unpaired samples.

- ITM (text encoder with image cross-attention; bidirectional SA) — judges whether a caption matches an image, with hard negatives drawn using ITC similarities.

- LM (decoder with shared cross-attention; causal SA) — generates captions token by token, conditioned on image features.

The total loss is a weighted sum, \[ \mathcal {L} = \lambda _{\mathrm {ITC}} \mathcal {L}_{\mathrm {ITC}} + \lambda _{\mathrm {ITM}} \mathcal {L}_{\mathrm {ITM}} + \lambda _{\mathrm {LM}} \mathcal {L}_{\mathrm {LM}}, \] with all parameters updated jointly.

- Why concurrency matters. Training the three tasks together stabilizes optimization: ITC provides a consistent alignment scaffold, ITM sharpens discrimination using those aligned features, and LM leverages the same cross-attended representations for grounded generation. Running them in parallel avoids forgetting and ensures improvements in one pathway benefit the others.

-

Summary. CapFilt first proposes better text (Captioner) and then selects reliable pairs (Filter). The resulting \(\mathcal {D}_{\mathrm {boot}}\) lets the final BLIP checkpoint learn alignment (ITC), grounding (ITM), and generation (LM) in one backbone—with cross-attention toggled on/off and self-attention switched between bidirectional (understanding) and causal (generation) purely via masks.

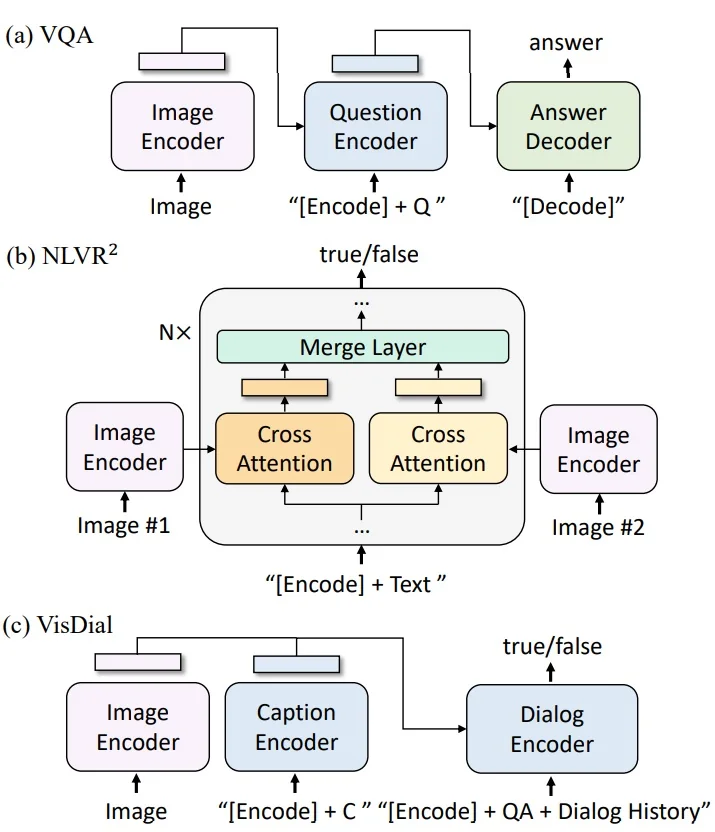

Downstream Usage After pretraining, the same backbone adapts flexibly:

- Retrieval (via ITC and ITM).

- Captioning (via LM).

- VQA (encode question + image, decode answer).

Experiments and Ablations

CapFilt Effectiveness Empirical studies confirm that the CapFilt pipeline provides consistent gains:

- Retrieval and Captioning. Models trained on the cleaned corpus outperform those trained on raw web text, even when both use the same number of image–text pairs.

- Quality vs. Quantity. Adding more noisy pairs does not close the gap; filtering clearly outperforms brute-force scaling, showing that data quality dominates raw scale.

- Retraining vs. Continuing. Restarting training from scratch on the purified set matches or exceeds continuing training on the noisy one, indicating that the benefit comes from improved supervision rather than extra steps.

Ablations Key ablation experiments highlight the necessity of both stages:

- Without Captioner. Relying only on web alt-text leaves a large fraction of pairs irrelevant or underspecified, hurting downstream generation.

- Without Filter. Using synthetic captions without selection reintroduces noise; performance falls sharply, showing that caption generation alone is insufficient.

- Joint vs. Decoupled. Sharing parameters between Captioner and Filter causes confirmation bias and weaker filtering; the decoupled design is essential.

Limitations and Future Work

- Scaling challenges. As models grow, balancing multiple objectives becomes harder; discriminative and generative losses can interfere without careful tuning.

- Dependence on bootstrapping. The final model’s quality is bounded by the effectiveness of the Captioner and Filter; errors in early stages propagate forward.

- Task balance. Equal treatment of ITC, ITM, and LM may not be optimal across domains; different applications may require task-specific weighting.

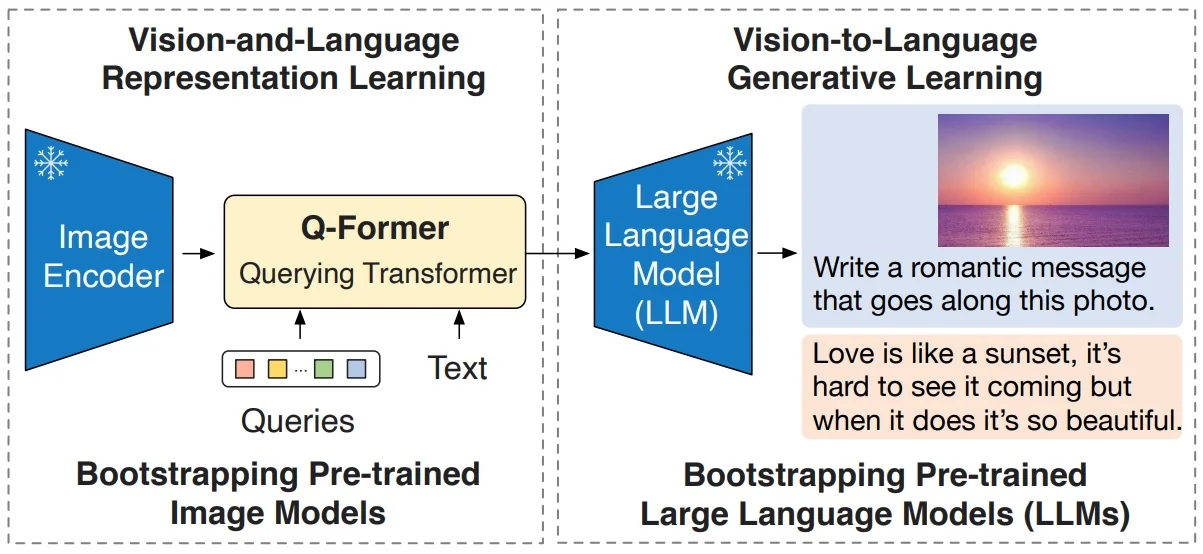

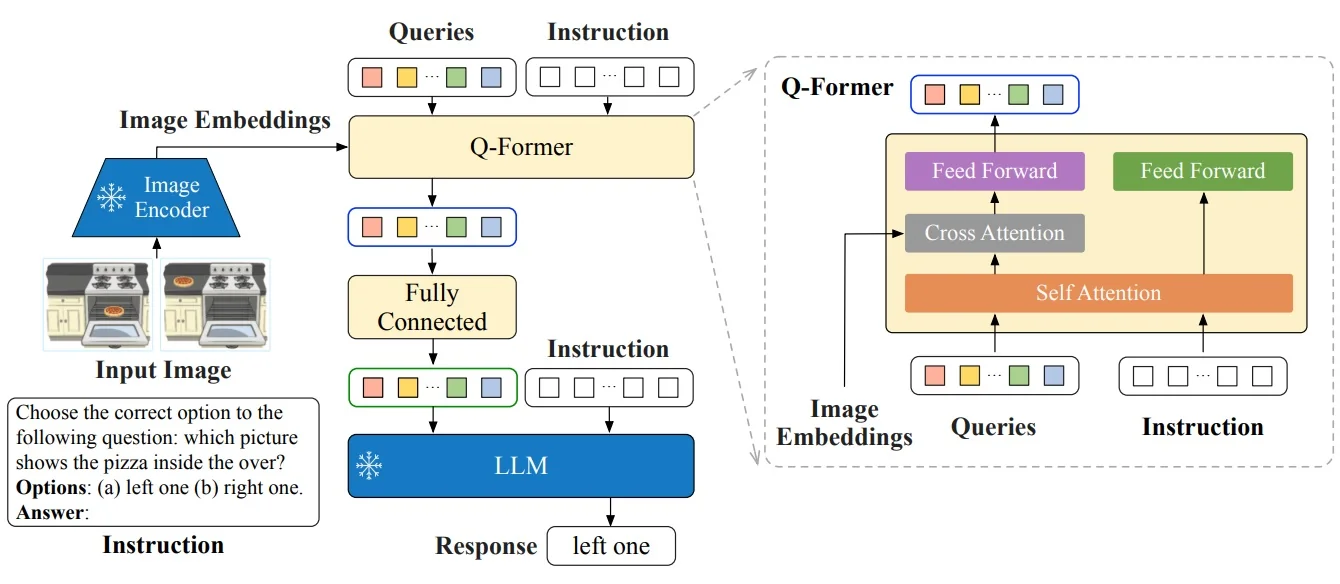

Toward BLIP-2 BLIP demonstrates that unified multi-task learning is feasible, but scaling to very large LLMs risks overwhelming multimodal fusion. BLIP-2 addresses this by freezing strong pretrained components (a vision encoder and an LLM) and inserting a lightweight connector (the Q-Former) to bridge them, retaining visual grounding while leveraging large-scale language priors.

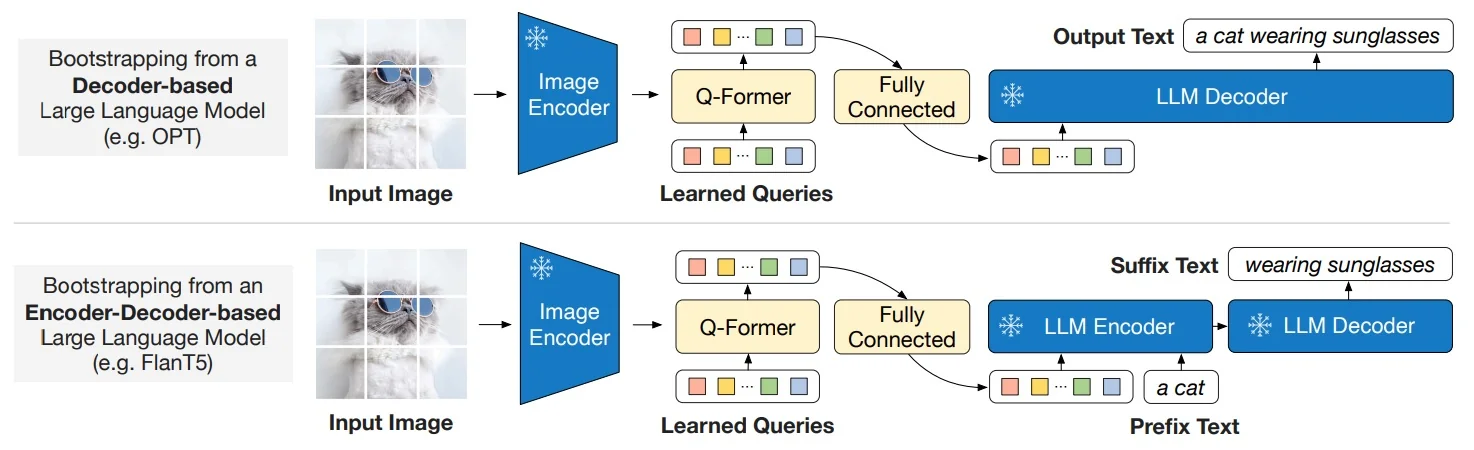

Enrichment 24.5.3: BLIP-2: Bridging Vision Encoders and LLMs via Q-Former

High-Level Idea BLIP-2 [333] moves away from BLIP’s heavy end-to-end training of both vision and text modules. In BLIP, the ViT image encoder and text transformer were jointly optimized with ITC, ITM, and LM losses. This achieved strong multimodal fusion, but came at huge computational cost: every improvement to the vision or text backbone required retraining the entire model, and the text side remained limited compared to emerging billion-parameter LLMs.

The BLIP-2 shift. Instead of training everything together, BLIP-2 leverages two frozen experts: a large pre-trained ViT (e.g., CLIP ViT-g or EVA-CLIP) and a large pre-trained LLM (e.g., OPT, FlanT5). Both remain untouched, preserving their strong unimodal priors. The only trainable component is a small Querying Transformer (Q-Former), equipped with a fixed set of learnable query tokens. These queries attend to frozen vision features, distill them into a compact representation, and pass them—via a thin projection—as soft prompts into the frozen LLM.

Why a two-stage curriculum? Training the Q-Former to talk to both the vision encoder and the LLM at once is unstable: the LLM has never seen visual tokens and cannot guide the alignment, while the ViT features are too high-dimensional and unstructured for direct prompting. Splitting training stabilizes learning and enforces a clear division of labor: first teach the Q-Former to see with the ViT alone, then teach it to communicate with the frozen LLM.

Two-stage curriculum.

- Stage 1 (Vision–Language Representation Learning): The Q-Former is trained with a frozen ViT, using BLIP-style objectives (contrastive, matching, generation) to ensure its query tokens capture text-relevant visual features. The LLM is not involved.

- Stage 2 (Vision-to-Language Generation): The Q-Former outputs are linearly projected and fed into the frozen LLM. Only the Q-Former is updated, so it learns to “speak the LLM’s language,” turning visual summaries into effective soft prompts for text generation.

In short, BLIP-2 improves over BLIP by freezing powerful unimodal backbones, introducing a small trainable bridge (the Q-Former), and adopting a staged curriculum that first teaches the bridge to see, then teaches it to talk.

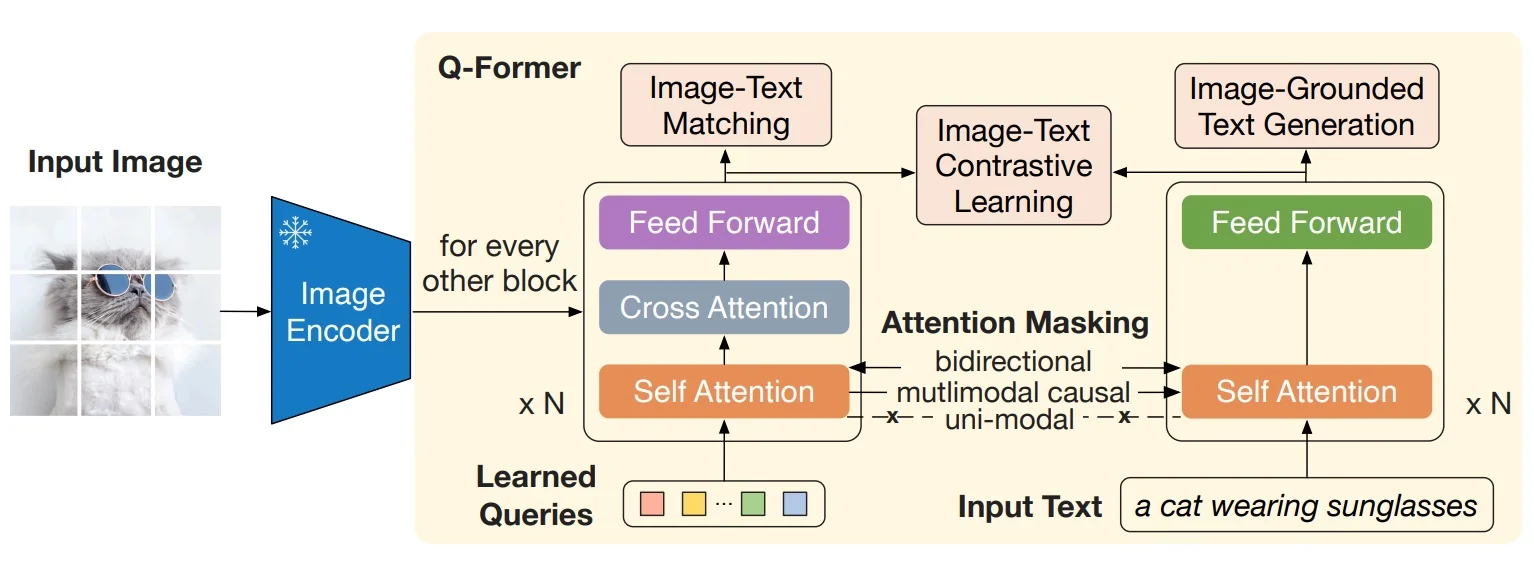

Method: A Small Q-Former Bridging Two Frozen Experts

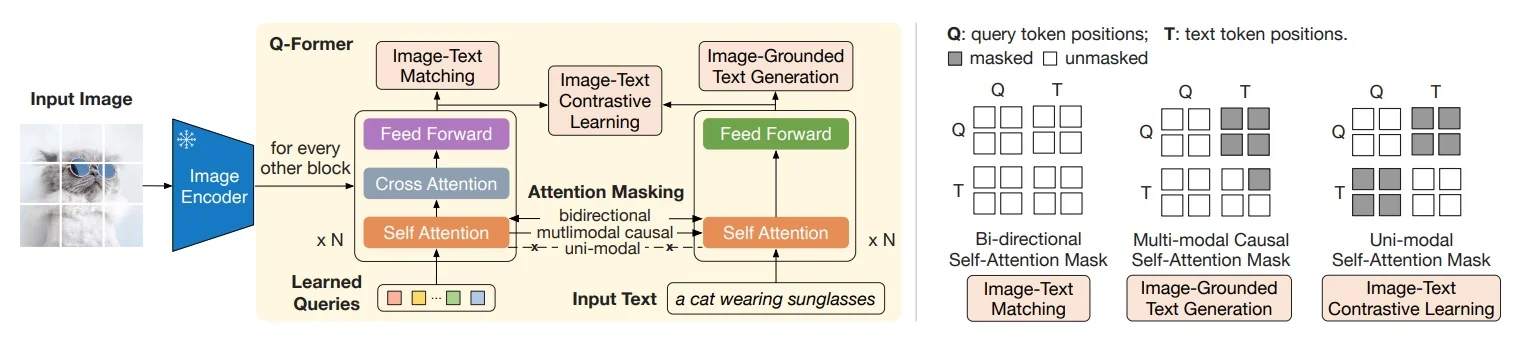

Stage 1: Vision–Language representation with a frozen image encoder Freeze the image encoder (e.g., CLIP/EVA ViT). Train only the Q-Former (and small heads) to extract text-relevant visual summaries. The Q-Former contains \(K\) learnable queries that self-attend and cross-attend to frozen visual tokens. Optimize three objectives (like in 24.4.5.0):

- ITC (Image–Text Contrastive). Learn independent visual/text embeddings for retrieval; align matched pairs and repel mismatches.

- ITM (Image–Text Matching). Enable fine-grained discrimination under bidirectional Q–Text interaction; predict match vs. non-match.

- Image-grounded LM pretraining (masked). Allow text to attend to queries while keeping text causal, preparing queries for generation.

Intuition. ITC yields globally aligned spaces; ITM injects pair-level grounding; masked conditioning prepares Q to act as a compact visual prompt.

Stage 2: Vision-to-language generation with a frozen LLM Keep the LLM frozen. Insert a linear projection from Q-Former outputs to the LLM token space and train (Q-Former + projection) with next-token prediction on caption/instruction data. The LLM consumes the \(K\) projected query tokens prepended to the textual prompt, enabling zero-shot, instruction-following image-to-text generation without tuning the LLM.

Two-Stage Curriculum: What Trains When and Why Stage 1 (learn to see): Freeze the image encoder; train only the Q-Former on paired image–text data. The three masks in Fig. 24.41 are used jointly so the queries learn to (a) summarize visual content independently of text (ITC), (b) fuse with text for pair verification (ITM), and (c) carry all image information needed to describe the text under causal decoding (image-grounded generation). Intuition: Before “talking” to a frozen LLM, Q must first become a compact, language-relevant summary of the image; otherwise the modality gap is too wide and training is brittle.

Stage 2 (learn to talk): Keep the image encoder and the LLM frozen. Feed the trained queries through a small projection into the LLM’s embedding space and optimize a language-modeling loss while updating only the Q-Former (and the projection). Intuition: With Stage 1, Q already encodes text-relevant visual evidence; Stage 2 teaches Q to present that evidence as a short “soft prompt” the LLM can use without disrupting its linguistic knowledge.

Objectives (concise math + intuition) Let \(v\) denote the Q-aggregated visual embedding and \(t\) a text embedding from the Q-Former stack (mask depends on the objective).

ITC (contrastive, uni-modal mask). \[ \mathcal {L}_{\mbox{ITC}} = -\frac {1}{N}\sum _{i=1}^{N} \Big [ \log \frac {\exp (\langle v_i,t_i\rangle /\tau )}{\sum _{j}\exp (\langle v_i,t_j\rangle /\tau )} + \log \frac {\exp (\langle t_i,v_i\rangle /\tau )}{\sum _{j}\exp (\langle t_i,v_j\rangle /\tau )} \Big ]. \] Why: Learn a shared space where matched pairs are close and mismatches are far, enabling retrieval.

ITM (matching, bi-directional mask). \[ \mathcal {L}_{\mbox{ITM}} = -\frac {1}{N}\sum _{i=1}^{N}\big [y_i\log p_i+(1-y_i)\log (1-p_i)\big ],\quad p_i=\sigma \!\big (W^\top f_{\mbox{fused}}(Q,T)\big ). \] Why: Enforce fine-grained grounding by classifying pair match vs. non-match on fused Q–T features (often with hard negatives).

Image-grounded generation (multimodal causal mask). \[ \mathcal {L}_{\mbox{IG}} = -\sum _{m=1}^{M}\log p\big (y_m \mid y_{<m},\, Q\big ). \] Why: Force queries to carry all image evidence needed for text under causal decoding, making Q a faithful visual prompt.

How the pieces fit during training

- Stage 1 (Q-Former only): Optimize \(\mathcal {L}_{\mbox{ITC}}+\mathcal {L}_{\mbox{ITM}}+\mathcal {L}_{\mbox{IG}}\) with the image encoder frozen and no LLM in the loop. This shapes Q into a compact, language-relevant visual interface.

- Stage 2 (Q-Former + frozen LLM): Project \(Q\) to the LLM’s token space and optimize a standard LM loss \(\mathcal {L}_{\mbox{LM}}=-\sum _m\log p_{\mbox{LLM}}(y_m\mid y_{<m},\,\mathrm {Proj}(Q))\), updating only the Q-Former and projection. This teaches Q to “speak” to the LLM without altering the LLM itself.

| Models | #Trainable Params | Open-sourced? | Visual QA (VQAv2 test-dev) | Image Captioning (NoCaps val) | Image–Text Retrieval (Flickr test)

| |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VQA acc. | CIDEr | SPICE | TR@1 | IR@1 | ||||

| BLIP [23] | 583M | \(\checkmark \) | – | 113.2 | 14.8 | 96.7 | 86.7 | |

| SimVLM [25] | 1.4B | \(\times \) | – | 112.2 | – | – | – | |

| BEIT-3 [26] | 1.9B | \(\times \) | – | – | – | 94.9 | 81.5 | |

| Flamingo [27] | 10.2B | \(\times \) | 56.3 | – | – | – | – | |

| BLIP-2 | 188M | \(\checkmark \) | 65.0 | 121.6 | 15.8 | 97.6 | 89.7 | |

| Model | #Trainable | Flickr30K Zero-shot (1K) | COCO Finetuned (5K) |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Image\(\rightarrow \)Text | Text\(\rightarrow \)Image | Image\(\rightarrow \)Text | Text\(\rightarrow \)Image |

||||||||||

| R@1 | R@5 | R@10 | R@1 | R@5 | R@10 | R@1 | R@5 | R@10 | R@1 | R@5 | R@10 | ||

Dual-encoder models |

|||||||||||||

| CLIP [28] | 428M | 88.0 | 98.7 | 99.4 | 68.7 | 90.6 | 95.2 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| ALIGN [29] | 820M | 88.6 | 98.7 | 99.7 | 75.7 | 93.8 | 96.8 | 77.0 | 93.5 | 96.9 | 59.9 | 83.3 | 89.8 |

| FILIP [30] | 417M | 89.8 | 99.2 | 99.8 | 75.0 | 93.4 | 96.3 | 78.9 | 94.4 | 97.4 | 61.2 | 84.3 | 90.6 |

| Florence [31] | 893M | 90.9 | 99.1 | – | 76.7 | 93.6 | – | 81.8 | 95.2 | – | 63.2 | 85.7 | – |

| BEIT-3 [26] | 1.9B | 94.9 | 99.9 | 100.0 | 81.5 | 95.6 | 97.8 | 84.8 | 96.5 | 98.3 | 67.2 | 87.7 | 92.8 |

Fusion-encoder models |

|||||||||||||

| UNITER [32] | 303M | 83.6 | 95.7 | 97.7 | 68.7 | 89.2 | 93.9 | 65.7 | 88.6 | 93.8 | 52.9 | 79.9 | 88.0 |

| OSCAR [33] | 345M | – | – | – | – | – | – | 70.0 | 91.1 | 95.5 | 54.0 | 80.8 | 88.5 |

| VinVL [34] | 345M | – | – | – | – | – | – | 75.4 | 92.9 | 96.2 | 58.8 | 83.5 | 90.3 |

Dual encoder + Fusion encoder re-ranking |

|||||||||||||

| ALBEF [35] | 233M | 94.1 | 99.5 | 99.7 | 82.8 | 96.3 | 98.1 | 77.6 | 94.3 | 97.2 | 60.7 | 84.3 | 90.5 |

| BLIP [23] | 446M | 96.7 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 86.7 | 97.3 | 98.7 | 82.4 | 95.4 | 97.9 | 65.1 | 86.3 | 91.8 |

| BLIP-2 ViT-L | 474M | 96.9 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 88.6 | 97.6 | 98.9 | 83.5 | 96.0 | 98.0 | 66.3 | 86.5 | 91.8 |

| BLIP-2 ViT-g | 1.2B | 97.6 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 89.7 | 98.1 | 98.9 | 85.4 | 97.0 | 98.5 | 68.3 | 87.7 | 92.6 |

Experiments & Ablations (Concise)

- Frozen experts preserve priors. Keeping the vision encoder and LLM frozen avoids catastrophic forgetting while enabling strong zero-shot transfer; most gains come from learning the interface (Q-Former + adapter).

- Masking matters. Ablating the uni-modal mask (ITC) degrades retrieval; ablating bidirectional (ITM) weakens grounding; removing causal conditioning harms generation quality—confirming each mask’s role.

- Number of queries (\(K\)). Too few queries underfit fine details; too many inflate compute with diminishing returns. Moderate \(K\) balances fidelity and LLM cost.

- Adapter simplicity. A single linear projection to the LLM embedding space is sufficient; heavier adapters show minor gains at higher cost.

- Curriculum order. Training Stage 1 (alignment/grounding) before Stage 2 (generation) stabilizes instruction-following performance; skipping Stage 1 reduces zero-shot quality.

Limitations & Future Work

Limitations.

- Bottleneck tightness. A fixed small \(K\) can miss region-level or fine-grained details without auxiliary heads/adapters.

- Static queries. Global queries lack explicit spatial/temporal structure; dense grounding or long video reasoning may require hierarchical or region/time-aware queries.

- Frozen LLM. Great for stability, but limits specialization under large domain shifts; PEFT helps but may be insufficient in niche domains.

Future Work.

- Hierarchical querying. Multi-scale or region/time-conditioned queries for dense tasks and long-horizon video.

- Adaptive \(K\). Dynamic selection based on content difficulty and prompt type to trade off detail vs. cost.

- Richer adapters/PEFT. Structured adapters (e.g., LoRA + gating) for selective LLM specialization while preserving generality.

- Unified multimodality. Extending the Q-Former interface to audio/motion and 3D inputs for broader perception–language reasoning.

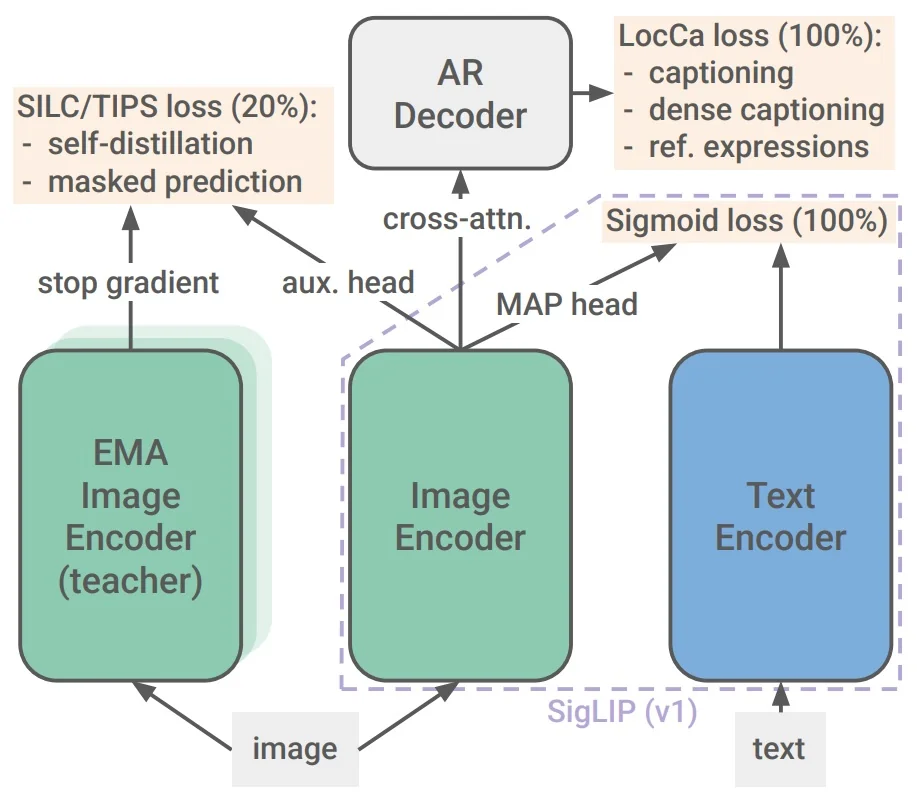

Enrichment 24.5.4: SigLIP 2: Multilingual & Dense Vision–Language Encoding

High-Level Overview SigLIP 2 keeps SigLIP’s efficient dual-encoder and pairwise sigmoid loss [758] (no cross-modal attention at test time), and adds training-only signals that teach the vision encoder three missing skills—where evidence is (localization), how patches relate (dense semantics), and how to cope with non-square layouts and non-English text (robustness). Concretely, we add:

- Localization (“where”). A lightweight decoder cross-attends to unpooled patch tokens and is trained for captioning, grounded captioning, and referring expressions [652]. This shapes patch-level spatial semantics but is discarded at test time.

- Dense semantics (“how patches relate”). A late consistency & masking tail (SILC/TIPS) aligns student crops to a full-image EMA teacher and predicts teacher features at masked patches [444, 415], yielding context-aware, part–whole coherent tokens.

- Input robustness (shapes & languages). A brief shape-aware tail either (i) releases size-specific specialists or (ii) trains a single NaFlex generalist that preserves native aspect ratios and supports multiple sequence lengths [116, 43]. Optional active curation improves small models by selecting informative pairs, and a multilingual mix improves cross-lingual transfer.

- Deployment unchanged. All additions are training-only; at inference the model reverts to the original fast SigLIP path: encoder-only dual towers with sigmoid scoring.

Foundational Reminder: How Sigmoid Loss (SigLIP) Works

Before describing the extensions in SigLIP 2, it is useful to recall the idea behind SigLIP [758]. Unlike CLIP, which aligns images and texts by contrasting every pair in a batch through a softmax-normalized InfoNCE loss, SigLIP treats alignment as a set of independent binary classification problems. Each image–text pair is scored by a logistic regressor: true pairs should have high probability, false pairs low. This removes the need for large batches and makes the training objective more flexible, while still encouraging globally aligned embeddings.

Compact formulation (per step) Let \(z^{\mbox{img}}_i, z^{\mbox{text}}_j \in \mathbb {R}^d\) be \(\ell _2\)-normalized embeddings, \(t=\exp (t')\) a learned temperature, and \(b\) a learned bias. The pairwise logit and sigmoid loss are \[ \ell _{ij} \;=\; t \,\big \langle z^{\mbox{img}}_i,\, z^{\mbox{text}}_j \big \rangle + b, \qquad \mathcal {L}_{\sigma } \;=\; - \sum _{i,j}\!\big [y_{ij}\log \sigma (\ell _{ij}) + (1-y_{ij})\log (1-\sigma (\ell _{ij}))\big ], \] with \(y_{ij}=1\) for a true match and \(0\) otherwise. This is the anchor signal that drives SigLIP training.

SigLIP 2 preserves this same core loss, and instead improves the learned representations by layering additional pretraining signals—such as a decoder for localization, late-stage consistency and masking, and resolution/multilingual adaptations—around the dual-encoder backbone. These new ingredients are training-only, leaving inference as efficient as the original SigLIP.

Method: A Staged Curriculum that Teaches Where, Detail, and Robustness

- Main phase (0–80%). Sigmoid image–text alignment plus a lightweight decoder for captioning/grounding: learn global “whether” while injecting “where” so patch tokens carry region evidence early.

- Consistency phase (80–100%). Add self-distillation and masked prediction (no freezing): enforce part–whole agreement and context completion once alignment/captioning are stable.

- Resolution tail (optional). Publish fixed-resolution specialists via short continuations, or train one NaFlex generalist that preserves native aspect ratios across multiple sequence lengths.

- Small-model curation (optional). For ViT-B/16, B/32, apply ACID to select high-learnability pairs and optimize the same sigmoid loss on curated data.

At inference, decoder/teacher/masking/curation are removed; the model is the SigLIP-style dual encoder.

Decoder for captioning and grounding (LocCa-style)

- Role. Add where to SigLIP’s whether: a small Transformer decoder (2–4 layers) cross-attends to unpooled patch tokens during pretraining and is discarded at test time.

-

Mechanism. Optimize three supervised objectives on top of patch tokens: \begin {align*} \mathcal {L}_\text {cap} &= -\sum _{t}\log p(w_t \mid w_{<t}, \{f_p\}) \quad \text {(image captioning)}\\ \mathcal {L}_\text {gcap} &= -\sum _{t}\log p(w_t \mid w_{<t}, \{f_p\}_{p\in \mathcal {R}}) \quad \text {(grounded captioning)}\\ \mathcal {L}_\text {ref} &= -\log \frac {\exp (\langle z_\text {phrase}, z_{\mathcal {R}}\rangle /\tau )}{\sum _k \exp (\langle z_\text {phrase}, z_{\mathcal {R}_k}\rangle /\tau )} \quad \text {(referring expressions)} \end {align*}

where \(f_p\) are patch features, \(\mathcal {R}\) a region (box/mask), and \(z_{\mathcal {R}}\) a pooled region embedding. Region–text pairs are auto-mined with n-grams and open-vocabulary detectors [652]. The combined loss \(\mathcal {L}_\mbox{dec}=\sum \lambda _\bullet \mathcal {L}_\bullet \) is added to the sigmoid anchor.

- Effect. Patch tokens become spatially grounded (who/what/where), improving transfer to grounding/OCR while keeping deployment cost unchanged.

Late self-distillation and masked prediction (SILC/TIPS-style)

- Role. Upgrade patch tokens from global proxies to locally coherent features via two self-supervised signals.

-

Mechanism (added late). Use an EMA teacher (full image) and multiple student views (crops/augments), applied to vision-only augmented views with small weights: \begin {align*} \mathcal {L}_\text {cons} &= \| g(z^\text {pool}_s) - g(z^\text {pool}_t) \|_2^2 \quad \text {(SILC: global consistency)}\\ \mathcal {L}_\text {mask} &= \sum _{m\in \mathcal {M}} \big \| h(f^s_{\setminus m}) - f^t_m \big \|_2^2 \quad \text {(TIPS: masked per-patch completion)} \end {align*}

with one teacher view, eight student crops, EMA decay \(\approx 0.999\), and small projection heads \(g,h\) [444, 415].

- Effect. Crops align with full-image semantics; masked regions are predictable from context. Dense-task transfer improves without any inference change.

Resolution and aspect-ratio adaptation Goal. Eliminate square-warping drift while preserving encoder-only runtime.

- Fixed-resolution continuation (specialists). From \(\sim \)95% progress, resume briefly at a new grid (e.g., \(14{\times }14\!\to \!24{\times }24\)): switch input resize, bilinearly (anti-aliased) retarget 2D positional embeddings \[ PE'_{u',v'}=\sum _{u,v}\alpha _{u,v\to u',v'}\,PE_{u,v},\quad \sum _{u,v}\alpha _{u,v\to u',v'}=1, \] and optionally adapt the patch stem if patch size changes. Continue with the same losses; publish size-specific checkpoints at minimal cost.

- NaFlex variant (one generalist). Train a single checkpoint that preserves native aspect ratios and supports multiple lengths [116, 43]. Per batch: sample \(L\!\in \!\{128,256,576,784,1024\}\); resize so \(H,W\) are patch-size multiples with minimal padding; bilinearly resize the 2D positional grid to \((H,W)\); mask padding in attention/pooling: \[ \mbox{Attn}(Q,K,V,M)=\mbox{softmax}\!\big (\tfrac {QK^\top }{\sqrt {d}}+M\big )V,\quad M_{ij}=\begin {cases}-\infty& \mbox{if pad}\\0&\mbox{otherwise.}\end {cases} \] Omit consistency/masking here for stability. Outcome: one encoder that “bends without warping” on documents/UIs/panoramas with no runtime penalty.

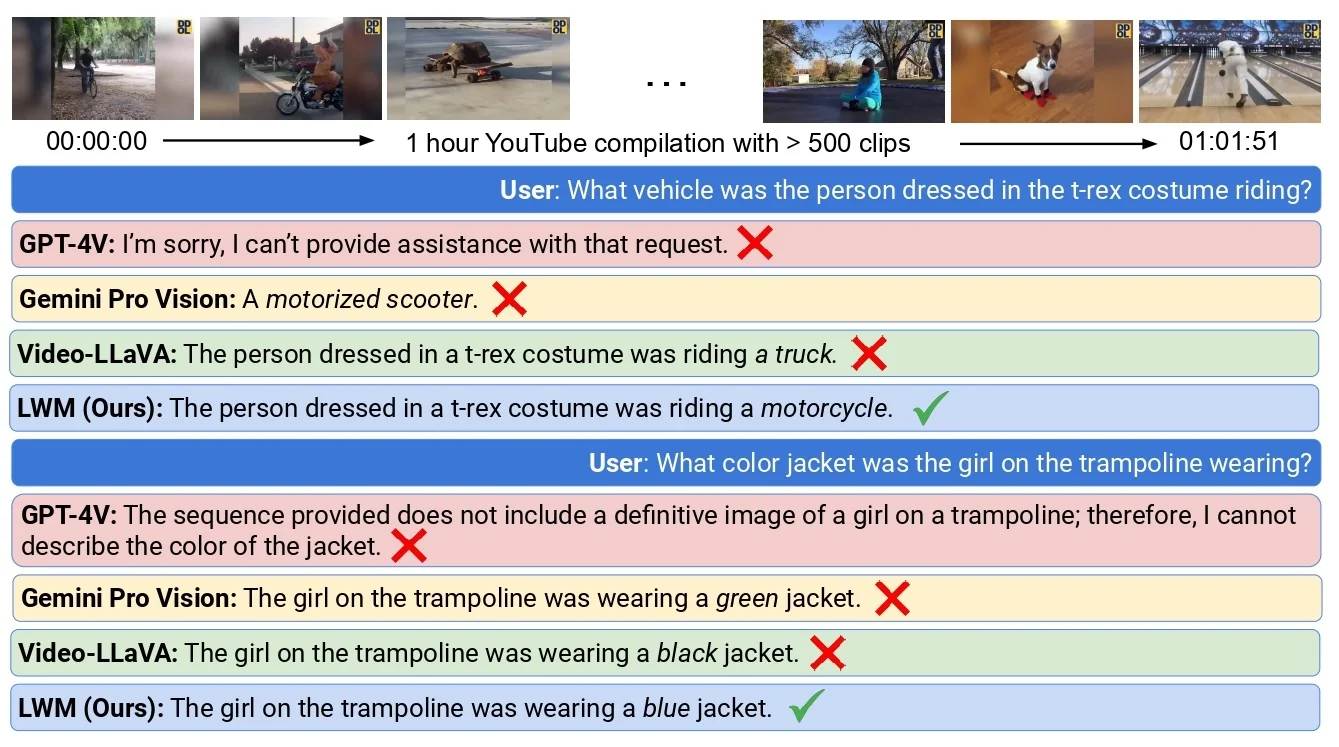

Curation-focused fine-tuning for small models Goal. Lift B-sized checkpoints where data quality, not capacity, is limiting.

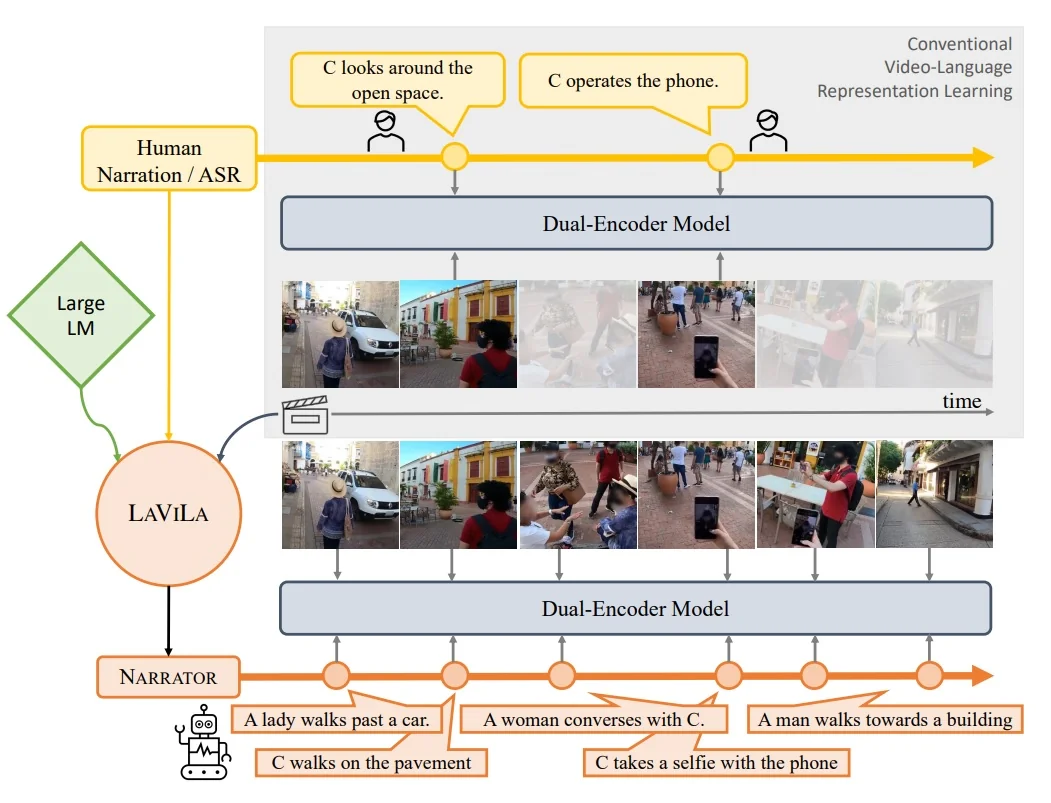

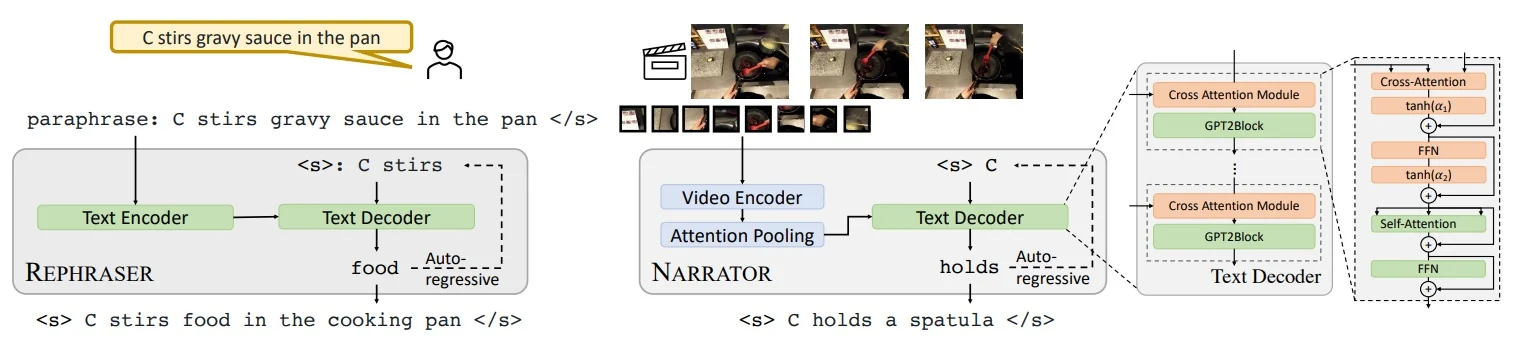

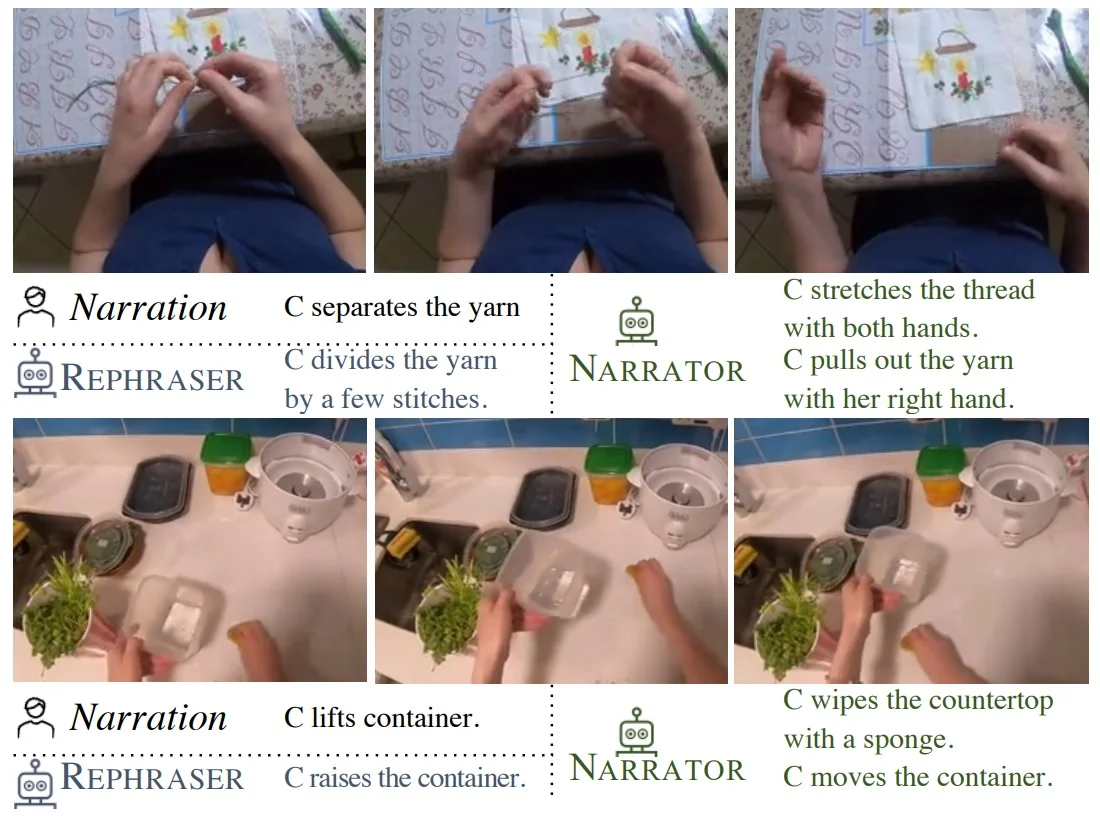

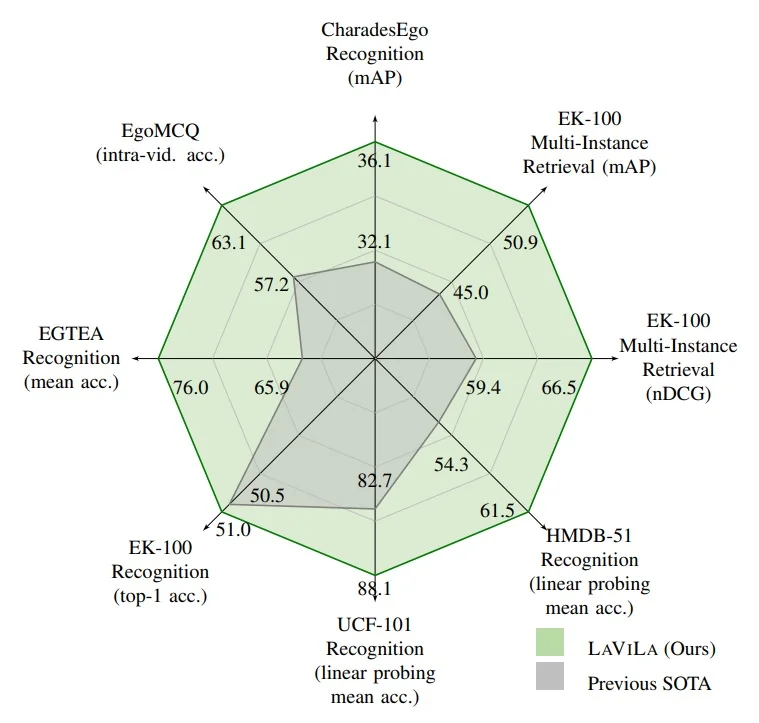

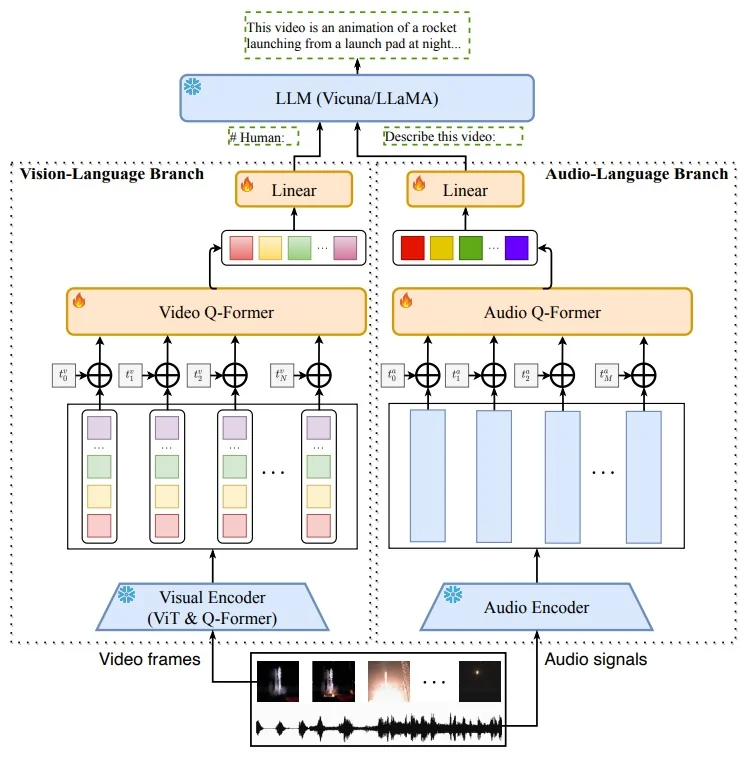

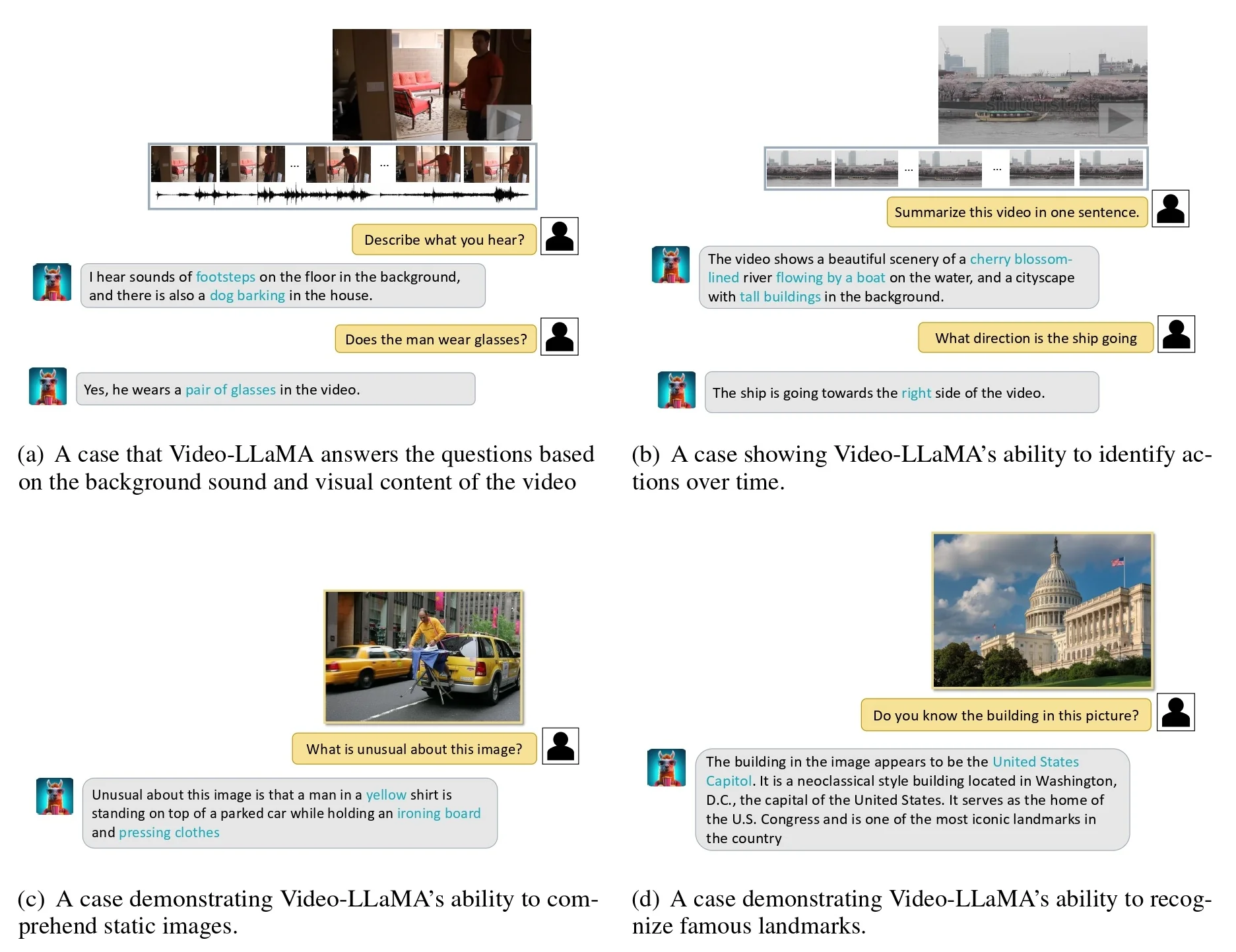

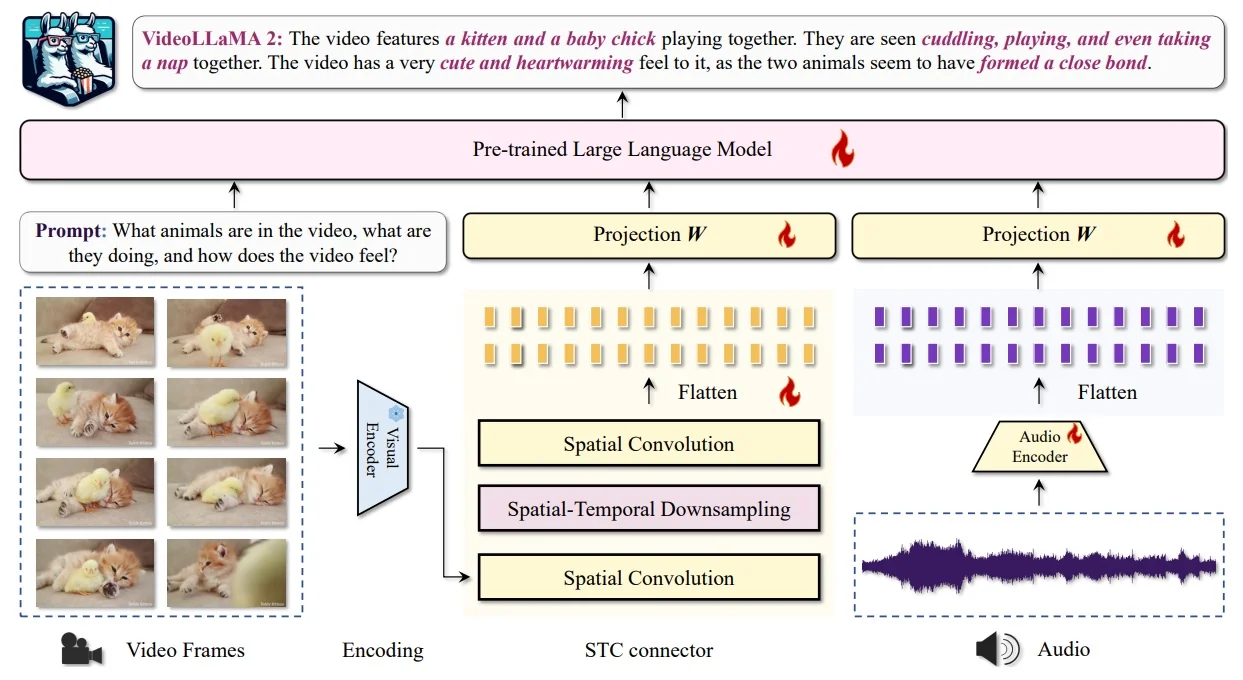

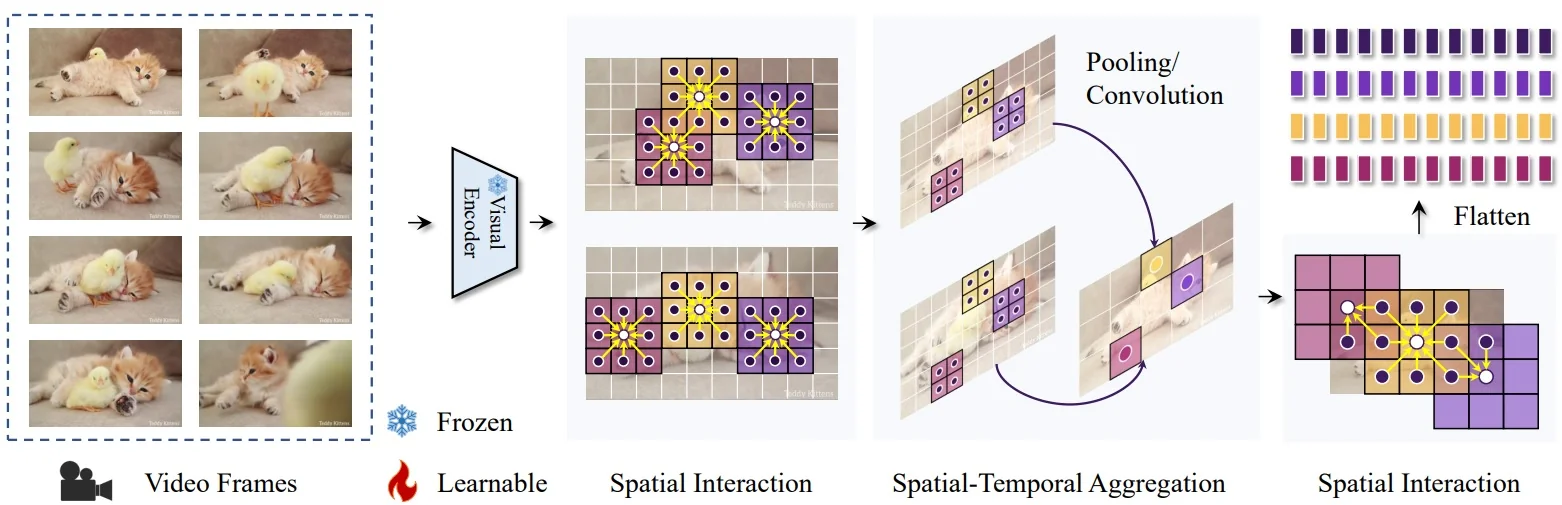

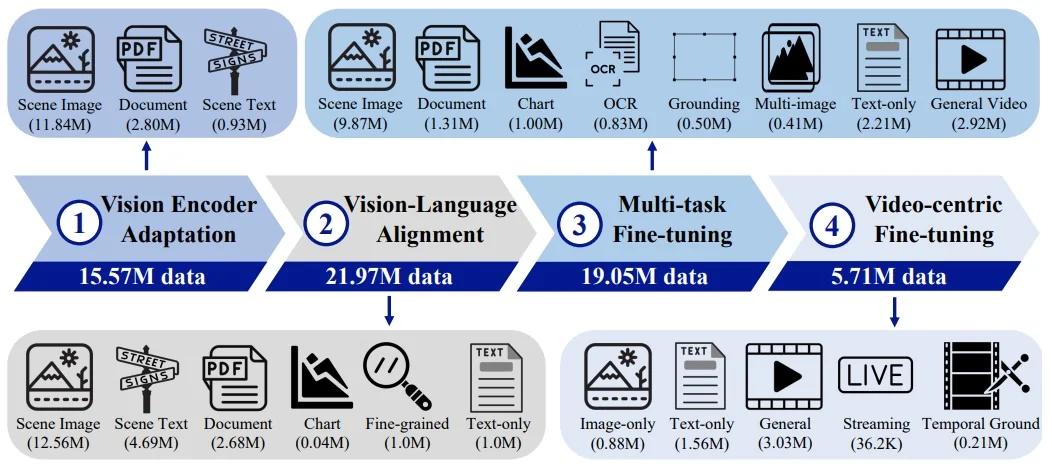

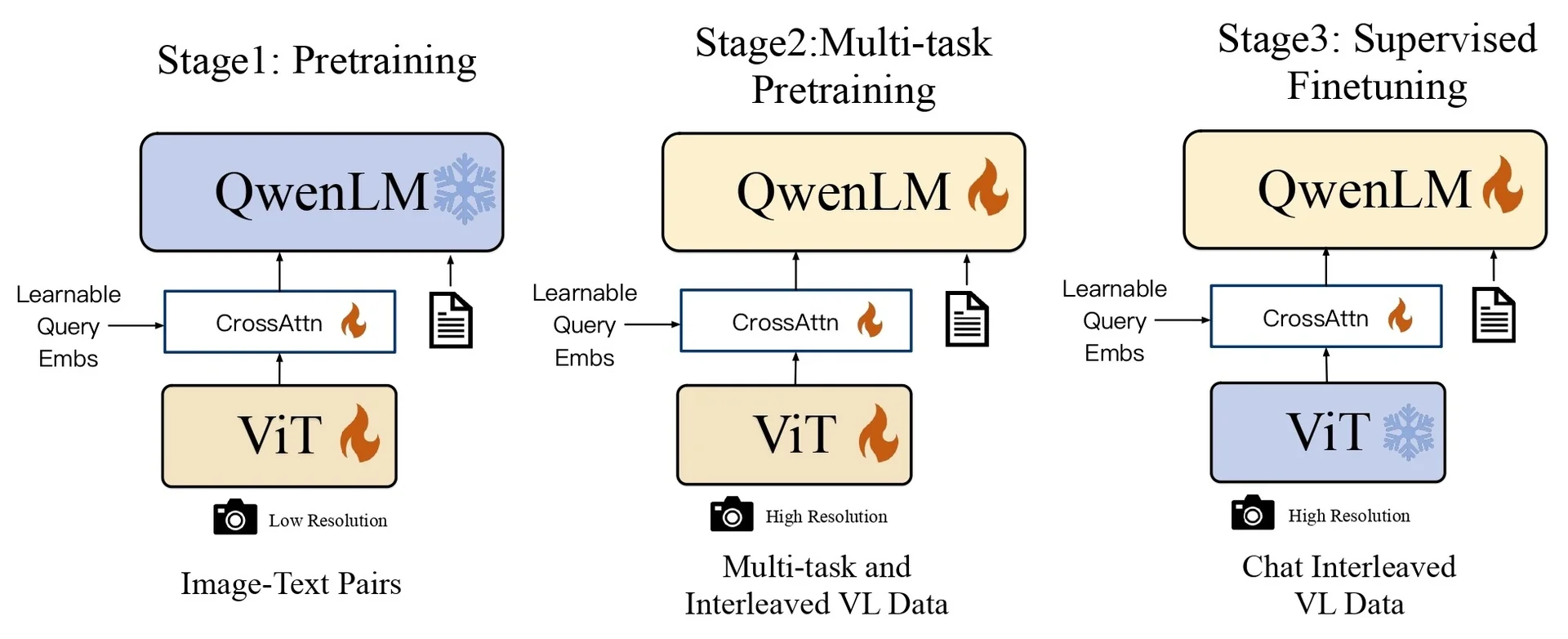

- ACID in SigLIP 2 [637]. Distill through data (selection, not logits). For a super-batch \(\mathcal {S}\), score pairs with teacher confidence and student uncertainty, \[ \phi _{ij}=\sigma (\ell ^T_{ij})\cdot H(\sigma (\ell ^S_{ij})),\quad H(p)=-[p\log p+(1-p)\log (1-p)], \] keep the top-\(k\) by \(\phi \), and optimize the same sigmoid loss on this curated subset. A single strong teacher (fine-tuned on a curated billion-pair mix) suffices.