Lecture 20: Generative Models II

20.1 VAE Training and Data Generation

In the previous chapter, we introduced the Evidence Lower Bound (ELBO) as a tractable surrogate objective for training latent variable models. We now dive deeper into how this lower bound is used in practice, detailing each component of the architecture and training pipeline.

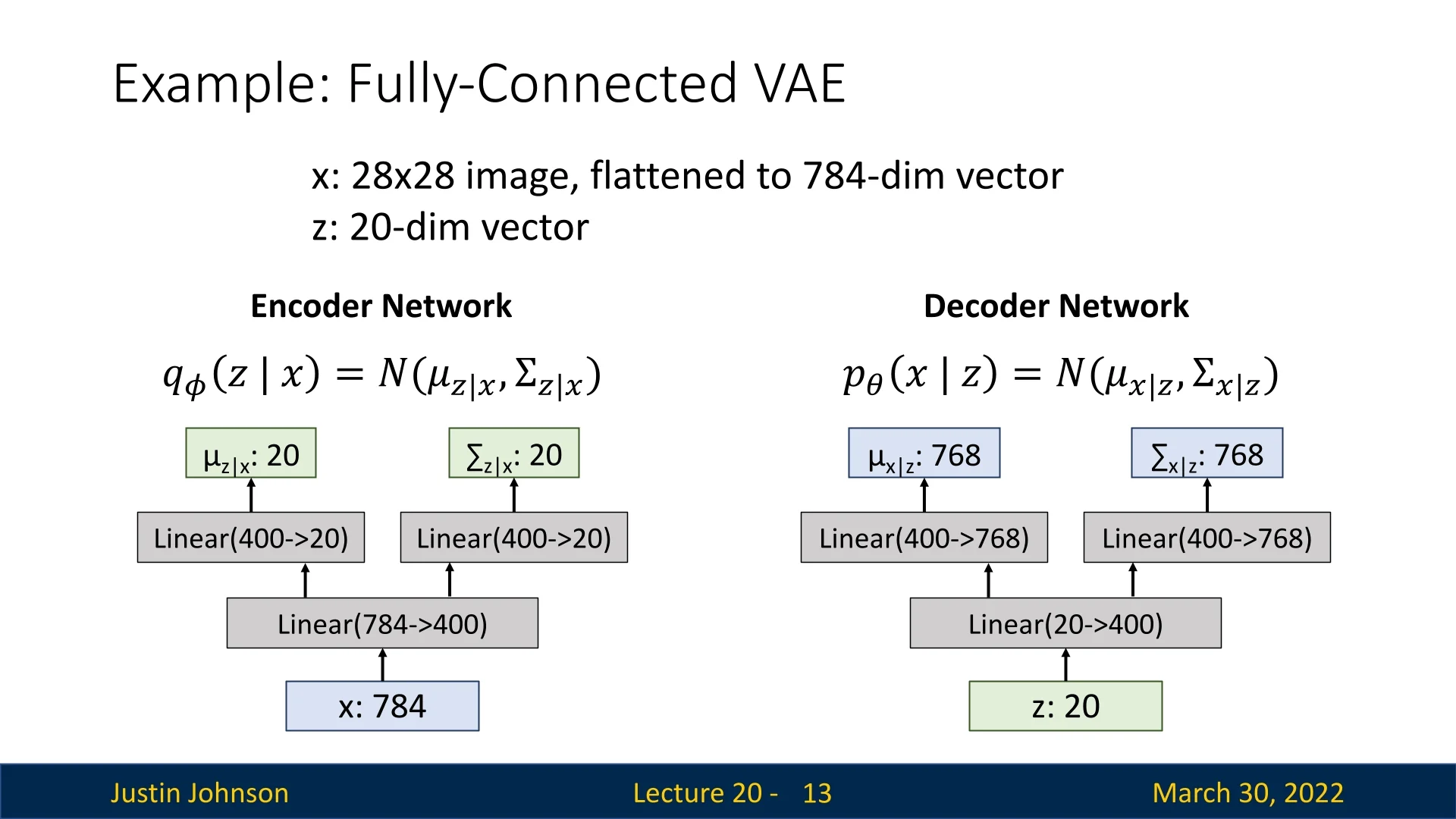

20.1.1 Encoder and Decoder Architecture: MNIST Example

Consider training a VAE on the MNIST dataset. Each MNIST image is \(28 \times 28\) grayscale, flattened into a 784-dimensional vector \( \mathbf {x} \in \mathbb {R}^{784} \). We choose a 20-dimensional latent space \( \mathbf {z} \in \mathbb {R}^{20} \).

20.1.2 Training Pipeline: Step-by-Step

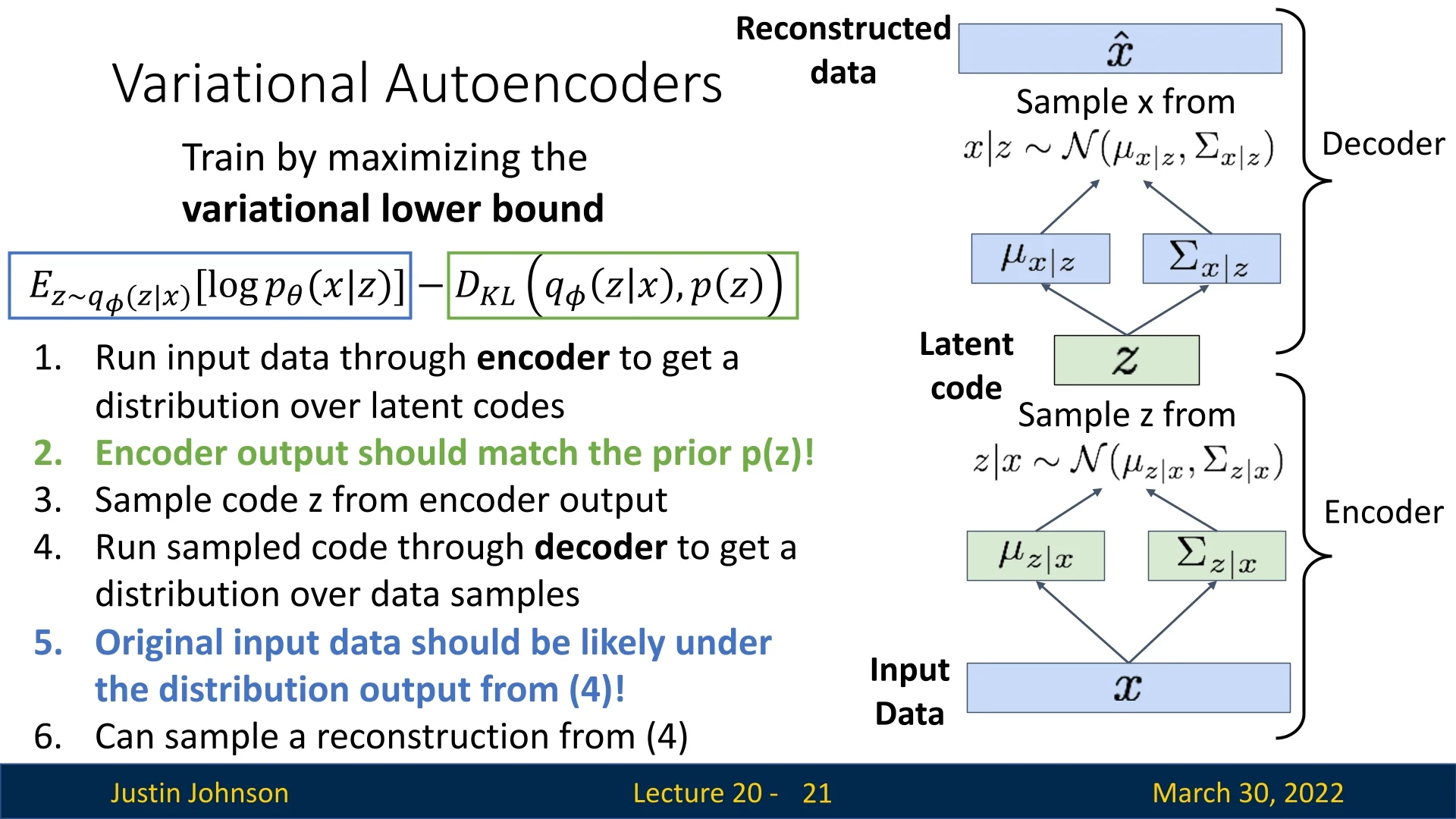

The ELBO Objective Recall from our theoretical derivation that our ultimate goal is to maximize the marginal log-likelihood of the data, \(\log p_\theta (\mathbf {x})\). However, computing this probability directly involves an intractable integral over the high-dimensional latent space. To circumvent this, we maximize a tractable surrogate objective known as the Evidence Lower Bound (ELBO):

\begin {equation} \log p_\theta (\mathbf {x}) \geq \underbrace {\mathbb {E}_{\mathbf {z} \sim q_\phi (\mathbf {z} \mid \mathbf {x})} \left [ \log p_\theta (\mathbf {x} \mid \mathbf {z}) \right ]}_{\mbox{reconstruction term}} - \underbrace {D_{\mathrm {KL}} \left (q_\phi (\mathbf {z} \mid \mathbf {x}) \,\|\, p(\mathbf {z}) \right )}_{\mbox{KL regularization}}. \label {eq:chapter20_elbo} \end {equation}

We train two neural networks simultaneously—the encoder (inference network) and the decoder (generative network)—to maximize this lower bound. Since standard deep learning frameworks (like PyTorch or TensorFlow) are designed to minimize loss functions, we formally define the VAE Loss as the negative ELBO: \begin {equation} \mathcal {L}_{\mbox{VAE}} = - \mbox{ELBO}. \label {eq:chapter20_vae_loss_def} \end {equation}

Crucial nuance: Minimizing this loss is not strictly equivalent to maximizing the true data likelihood. We are optimizing a lower bound. The gap between the log-likelihood and the ELBO is exactly the expected KL divergence between our approximate posterior and the true posterior, \(\log p_\theta (\mathbf {x}) - \mbox{ELBO} = \mathbb {E}_{\mathbf {x} \sim p_{\mbox{data}}} \left [ D_{\mathrm {KL}}\big (q_\phi (\mathbf {z} \mid \mathbf {x}) \,\|\, p_\theta (\mathbf {z} \mid \mathbf {x})\big ) \right ]\). If the encoder is not expressive enough to match the true posterior, this gap remains strictly positive. This fundamental limitation—optimizing a bound rather than the exact marginal likelihood—is one reason why later generative model families, such as diffusion models and flow-based models, explore alternative training objectives that do not rely on variational lower bounds.

For a high-level discussion on the properties of latent spaces (e.g., the manifold hypothesis), please refer back to Section Lecture 19 (Chapter 19). Below, we detail the practical execution of the VAE training pipeline in six stages.

- 1.

- Run input \( \mathbf {x} \) through the encoder.

The encoder network \( q_\phi (\mathbf {z} \mid \mathbf {x}) \) processes the input image, but unlike a standard autoencoder, it does not output a single latent code. Instead, it predicts a probability distribution over the latent space. Specifically, for a latent dimensionality \( J \), the encoder outputs two vectors: \[ \boldsymbol {\mu }_{z|x} \in \mathbb {R}^J \quad \mbox{and} \quad \boldsymbol {\sigma }^2_{z|x} \in \mathbb {R}^J \] These vectors parameterize a diagonal Gaussian distribution \( q_\phi (\mathbf {z} \mid \mathbf {x}) = \mathcal {N}(\boldsymbol {\mu }_{z|x}, \operatorname {diag}(\boldsymbol {\sigma }^2_{z|x})) \). In what follows, we will often abbreviate \(\boldsymbol {\mu }_{z|x}\) and \(\boldsymbol {\sigma }^2_{z|x}\) as \(\boldsymbol {\mu }\) and \(\boldsymbol {\sigma }^2\) for brevity.

Note on Stability: In many implementations, the encoder actually predicts log-variance, \(\log \boldsymbol {\sigma }^2\), rather than \(\boldsymbol {\sigma }^2\) directly. This improves numerical stability by mapping the variance domain \((0, \infty )\) to the real line \((-\infty , \infty )\). The variance is then recovered via an element-wise exponential.

- 2.

- Compute the KL divergence between the encoder’s

distribution and the prior.

To ensure the latent space remains well-behaved, we enforce a penalty if the encoder’s predicted distribution diverges from a fixed prior, typically the standard multivariate Gaussian \( p(\mathbf {z}) = \mathcal {N}(\mathbf {0}, \mathbf {I}) \).

Because both the posterior and prior are Gaussian, the Kullback-Leibler (KL) divergence has a convenient closed-form solution. We compute this simply by summing over all \( J \) latent dimensions: \begin {equation} D_{\mathrm {KL}}\big (q_\phi (\mathbf {z} \mid \mathbf {x}) \,\|\, p(\mathbf {z})\big ) = \frac {1}{2} \sum _{j=1}^{J} \left ( 1 + \log \sigma _j^2 - \mu _j^2 - \sigma _j^2 \right ). \label {eq:chapter20_vae_kl_closed_form} \end {equation} This term acts as a regularizer. It pulls the mean \( \boldsymbol {\mu } \) towards 0 and the variance \( \boldsymbol {\sigma }^2 \) towards 1. Without this term, the encoder could ”cheat” by clustering data points far apart (making \( \mu \) huge) or by shrinking the variance to effectively zero (making \( \sigma \to 0 \)), effectively collapsing the VAE back into a standard deterministic autoencoder.

- 3.

- Sample latent code \( \mathbf {z} \) using the Reparameterization Trick.

The decoder requires a concrete vector \( \mathbf {z} \) to generate an output. Therefore, we must sample from the distribution defined by \( \boldsymbol {\mu } \) and \( \boldsymbol {\sigma } \).

The Obstacle (Blocking Gradients): A naive sampling operation breaks the computation graph. Backpropagation requires continuous derivatives, but we cannot differentiate with respect to a random roll of the dice. If we simply sampled \( z \), the gradient flow would stop at the sampling node.

The Solution (Reparameterization): We use the reparameterization trick to bypass this block. We express \( \mathbf {z} \) as a deterministic transformation of the encoder parameters and an auxiliary noise source: \begin {equation} \mathbf {z} = \boldsymbol {\mu }_{z|x} + \boldsymbol {\sigma }_{z|x} \odot \boldsymbol {\epsilon }, \quad \boldsymbol {\epsilon } \sim \mathcal {N}(\mathbf {0}, \mathbf {I}). \label {eq:chapter20_vae_reparameterization} \end {equation} Practical Implementation Details:

- Source of Randomness: We sample a noise vector \(\boldsymbol {\epsilon } \in \mathbb {R}^J\) from \(\mathcal {N}(\mathbf {0}, \mathbf {I})\). This variable effectively ”holds” the stochasticity.

- Vectorization: In practice, we sample a unique \( \boldsymbol {\epsilon } \) for every data point in the batch during every forward pass.

- Gradient Flow: The operation \( \odot \) denotes element-wise multiplication. Crucially, because \( \boldsymbol {\epsilon } \) is treated as an external constant during the backward pass, gradients can flow freely through \( \boldsymbol {\mu } \) and \( \boldsymbol {\sigma } \) back to the encoder weights.

For a visual walkthrough of this mechanism, we recommend:

ML&DL Explained { Reparameterization Trick. - 4.

- Feed the sampled latent code \( \mathbf {z} \) into the decoder.

The decoder \( p_\theta (\mathbf {x} \mid \mathbf {z}) \) maps the sampled code \( \mathbf {z} \) back to the high-dimensional data space. It outputs the parameters of the likelihood distribution for the pixels (e.g., the predicted mean intensity for each pixel).

- 5.

- Evaluate the reconstruction likelihood.

We measure how well the decoder ”explains” the original input \( \mathbf {x} \) given the sampled code \( \mathbf {z} \). For real-valued images, we typically assume a factorized Gaussian likelihood with fixed variance. In this case, maximizing the log-likelihood is equivalent (up to an additive constant) to minimizing the squared \(\ell _2\) reconstruction error: \begin {equation} \mathcal {L}_{\mbox{recon}} \,\propto \, \left \| \mathbf {x} - \hat {\mathbf {x}} \right \|_2^2. \label {eq:chapter20_vae_recon_mse} \end {equation}

- 6.

- Combine terms to compute the total VAE Loss.

The final objective function is the sum of the reconstruction error and the regularization penalty: \begin {equation} \mathcal {L}_{\mbox{VAE}}(\mathbf {x}) = \underbrace {- \mathbb {E}_{\mathbf {z} \sim q_\phi (\mathbf {z} \mid \mathbf {x})} \left [\log p_\theta (\mathbf {x} \mid \mathbf {z})\right ]}_{\mbox{reconstruction loss}} + \underbrace {D_{\mathrm {KL}}\big (q_\phi (\mathbf {z} \mid \mathbf {x}) \,\|\, p(\mathbf {z})\big )}_{\mbox{regularization loss}}. \label {eq:chapter20_vae_total_loss} \end {equation}

The VAE “Tug-of-War” (Regularization vs. Reconstruction):

The VAE objective function creates a fundamental conflict between two opposing goals, forcing the model to find a useful compromise:

- The Reconstruction Term (Distinctness):

-

This term maximizes \(\mathbb {E}[\log p_\theta (\mathbf {x} \mid \mathbf {z})]\). It drives the encoder to be as precise as possible to minimize error. The Extreme Case: If left unchecked, the encoder would reduce the variance to zero (\(\sigma \to 0\)). The latent distribution would collapse into a Dirac delta function (a single point), effectively turning the VAE into a standard deterministic Autoencoder. While this minimizes reconstruction error, the model effectively “memorizes” the training data as isolated points, failing to learn the smooth, continuous manifold required for generating new images.

- The KL Term (Smoothness):

-

This term minimizes \(D_{\mathrm {KL}}(q_\phi (\mathbf {z} \mid \mathbf {x}) \,\|\, p(\mathbf {z}))\). It forces the encoder’s output to match the standard Gaussian prior (\(\mathcal {N}(0, I)\)), encouraging posteriors to be “noisy” and overlap. The Extreme Case: If left unchecked (i.e., if this regularization dominates), the encoder will ignore the input \(\mathbf {x}\) entirely to satisfy the prior perfectly. This phenomenon, known as Posterior Collapse, results in latent codes that contain no information about the input image, causing the decoder to output generic noise or average features regardless of the input.

The Result: This tension prevents the model from memorizing exact coordinates (Autoencoder) while preventing it from outputting pure noise (Posterior Collapse). The VAE settles on a “cloud-like” representation that is distinct enough to preserve content but smooth enough to allow for interpolation and generation.

Why a Diagonal Gaussian Prior?

We typically choose the prior \( p(\mathbf {z}) \) to be a unit Gaussian \( \mathcal {N}(\mathbf {0}, \mathbf {I}) \). While simple, this choice provides powerful benefits:

- Analytical Tractability: As seen in Equation 20.3, the KL divergence between two Gaussians can be computed without expensive sampling or integrals.

- Encouraging Disentanglement: The diagonal covariance structure assumes independence between dimensions. This biases the model towards allocating distinct generative factors to separate dimensions (e.g., “azimuth” vs. “elevation”) rather than entangling them, although in practice such disentanglement is not guaranteed.

- Manifold Smoothness: By forcing the posterior to overlap with the standard normal prior, we prevent the model from memorizing the training set (which would look like a set of isolated delta functions). Instead, the model learns a smooth, continuous manifold where any point sampled from \( \mathcal {N}(\mathbf {0}, \mathbf {I}) \) is likely to decode into a plausible image.

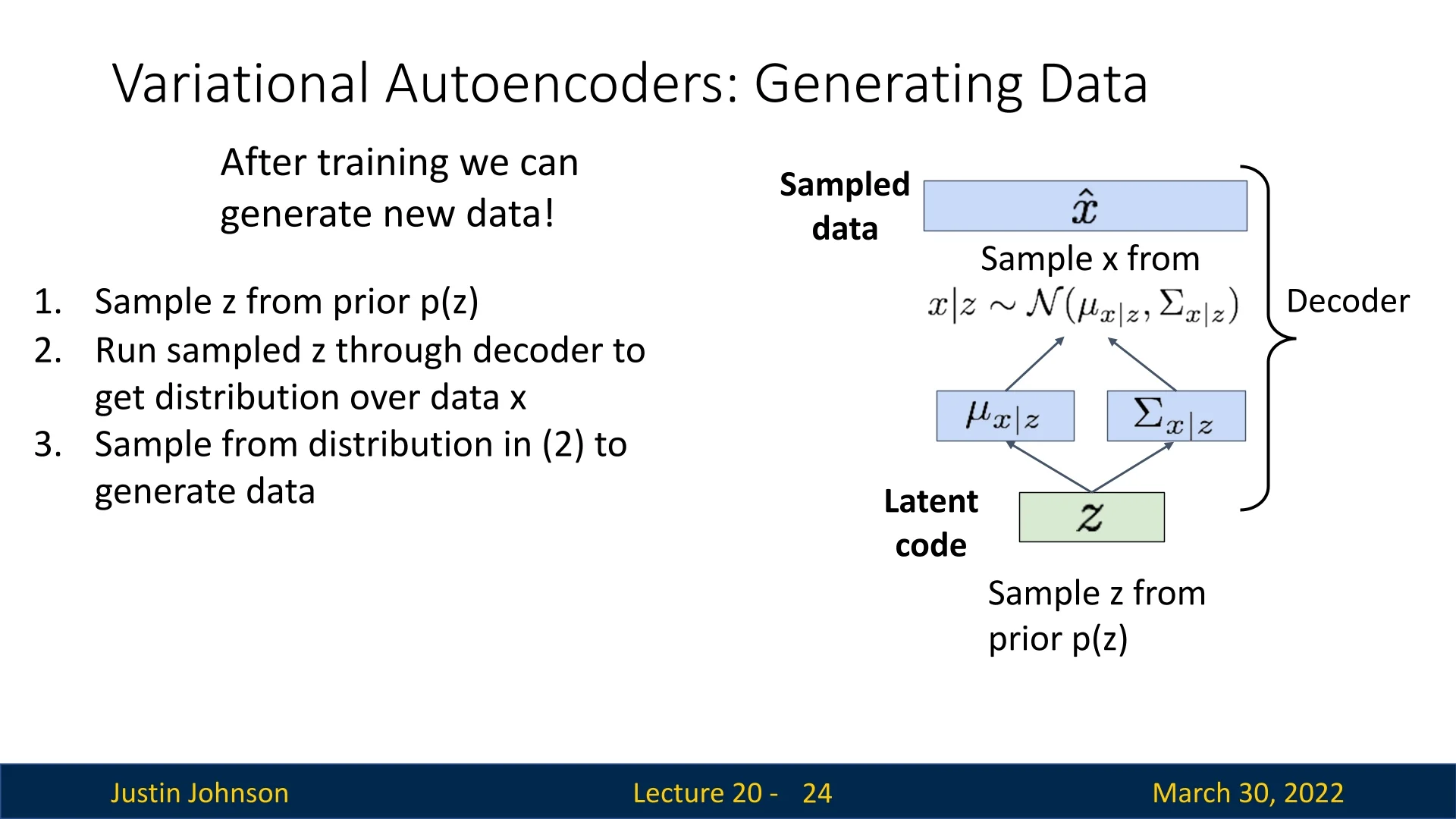

20.1.3 How Can We Generate Data Using VAEs?

Once a Variational Autoencoder is trained, we can use it as a generative model to produce new data samples. Unlike the training phase, which starts from observed inputs \( \mathbf {x} \), the generative process starts from the latent space.

Sampling Procedure To generate a new data point (e.g., a novel image), we follow a simple three-step process:

- 1.

- Sample a latent code \( \mathbf {z} \sim p(\mathbf {z}) \).

This draws from the prior distribution, which is typically set to \( \mathcal {N}(\mathbf {0}, \mathbf {I}) \). The latent space has been trained such that this prior corresponds to plausible latent factors of variation. - 2.

- Run the sampled \( \mathbf {z} \) through the decoder \( p_\theta (\mathbf {x} \mid \mathbf {z}) \).

This yields the parameters (e.g., mean and variance) of a probability distribution over possible images. - 3.

- Sample a new data point \( \hat {\mathbf {x}} \) from this output distribution.

Typically, we sample from the predicted Gaussian: \[ \hat {\mathbf {x}} \sim \mathcal {N}(\boldsymbol {\mu }_{x|z}, \operatorname {diag}(\boldsymbol {\sigma }^2_{x|z})) \] In some applications (e.g., grayscale image generation), one might use just the mean \( \boldsymbol {\mu }_{x|z} \) as the output.

This process enables the generation of diverse and novel data samples that resemble the training distribution, but are not copies of any specific training point.

20.2 Results and Applications of VAEs

Variational Autoencoders not only enable data generation but also support rich latent-space manipulation. Below, we summarize key empirical results and capabilities demonstrated in foundational works.

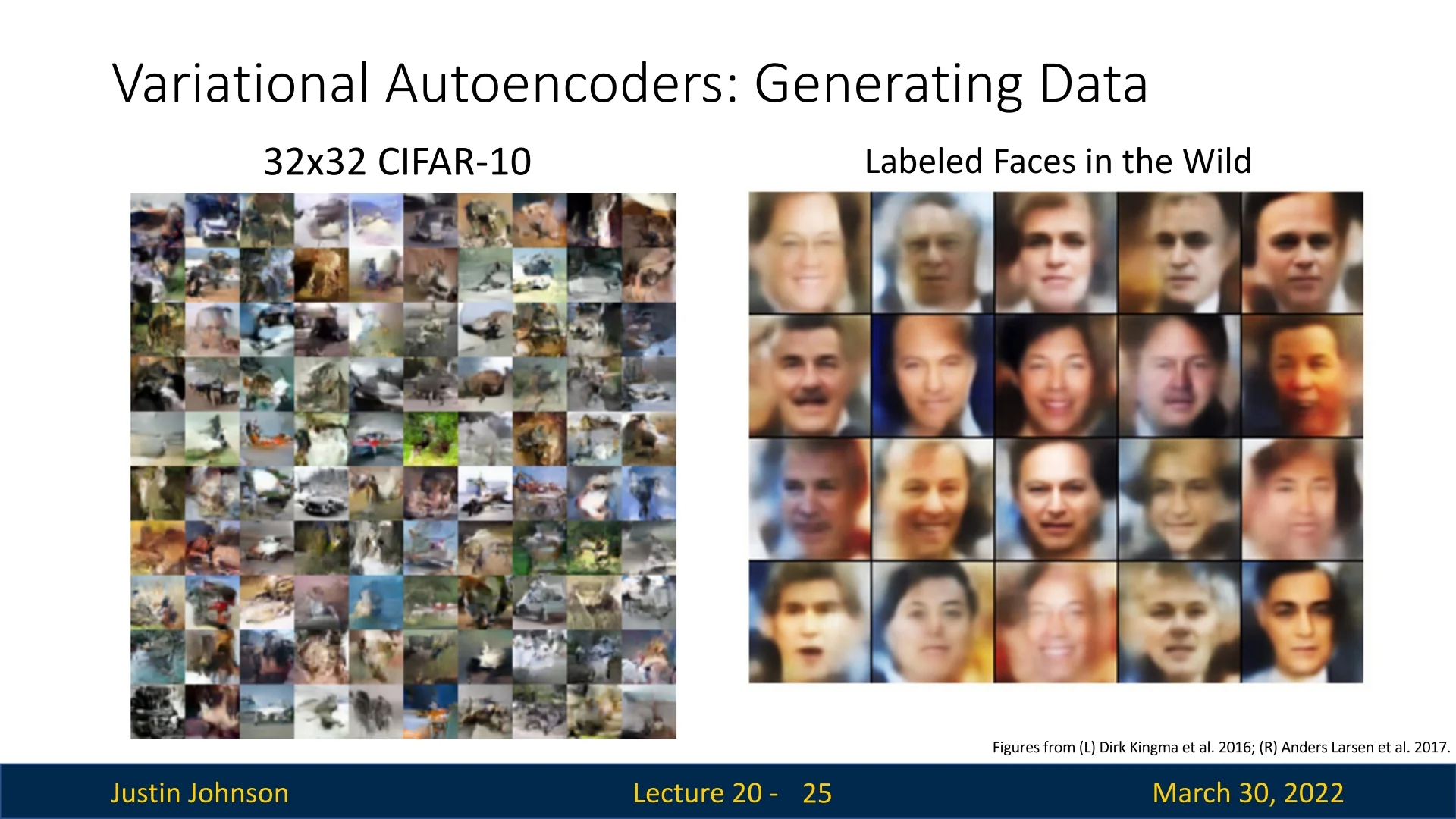

20.2.1 Qualitative Generation Results

Once trained, VAEs can generate samples that resemble the training data distribution. For instance:

- On CIFAR-10, generated samples are 32×32 RGB images with recognizable textures and object-like patterns.

- On the Labeled Faces in the Wild (LFW) dataset, VAEs generate realistic human faces, capturing high-level structures such as symmetry, eyes, hair, and pose.

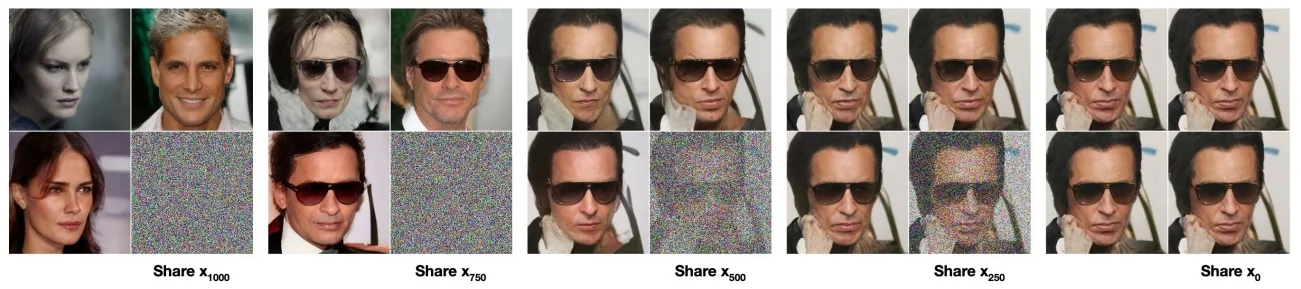

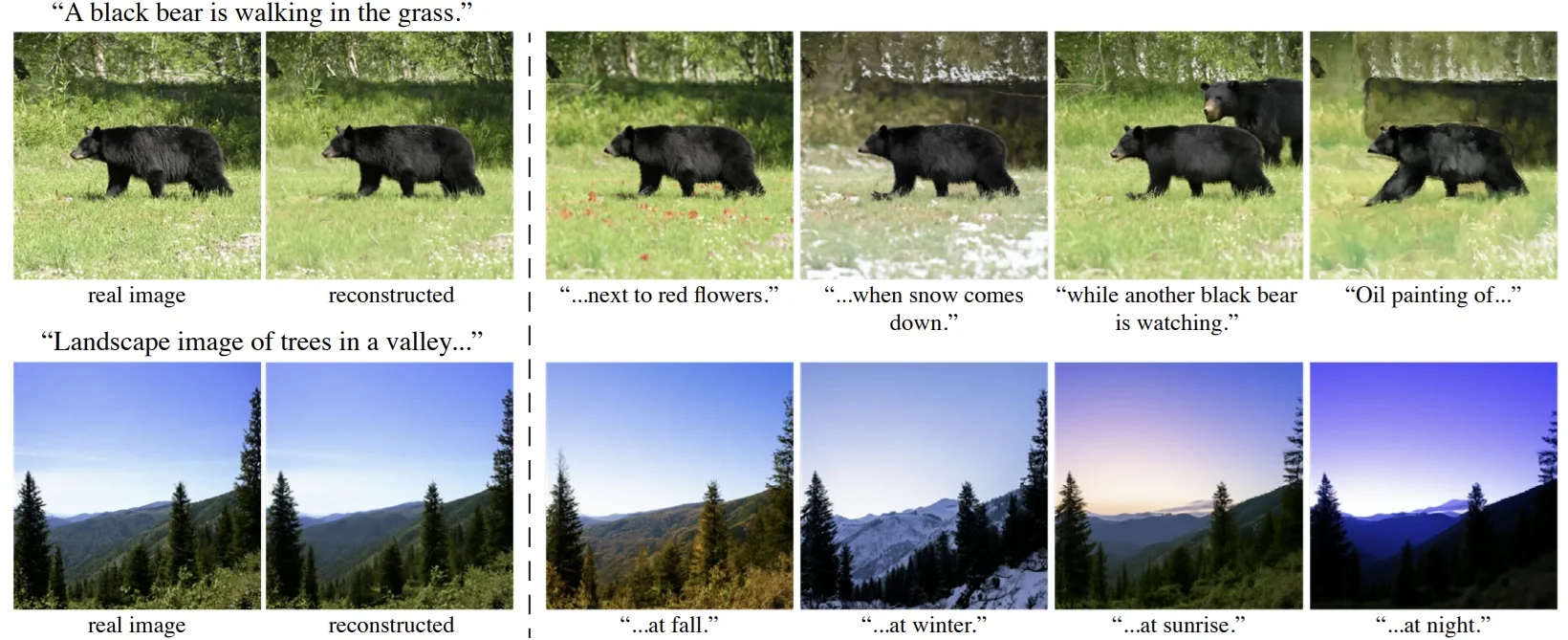

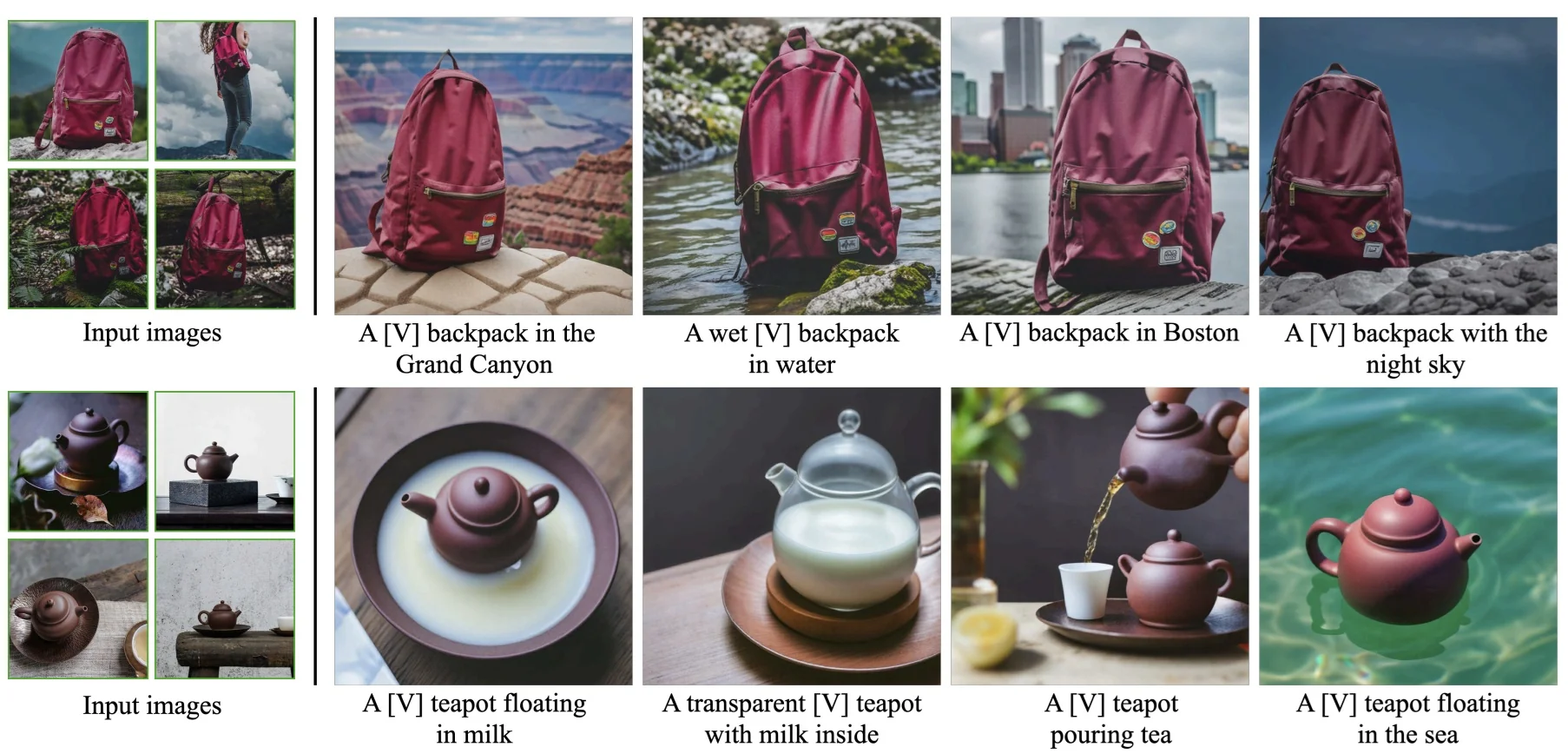

20.2.2 Latent Space Traversals and Image Editing

Once a VAE has been trained, we are no longer limited to simply reconstructing inputs. Because the latent prior \(p(\mathbf {z})\) is typically chosen to be a diagonal Gaussian, the model assumes that different coordinates of \(\mathbf {z}\) are a priori independent. This structural assumption makes it natural to manipulate individual latent dimensions and observe how specific changes in the code \(\mathbf {z}\) manifest in the generated data.

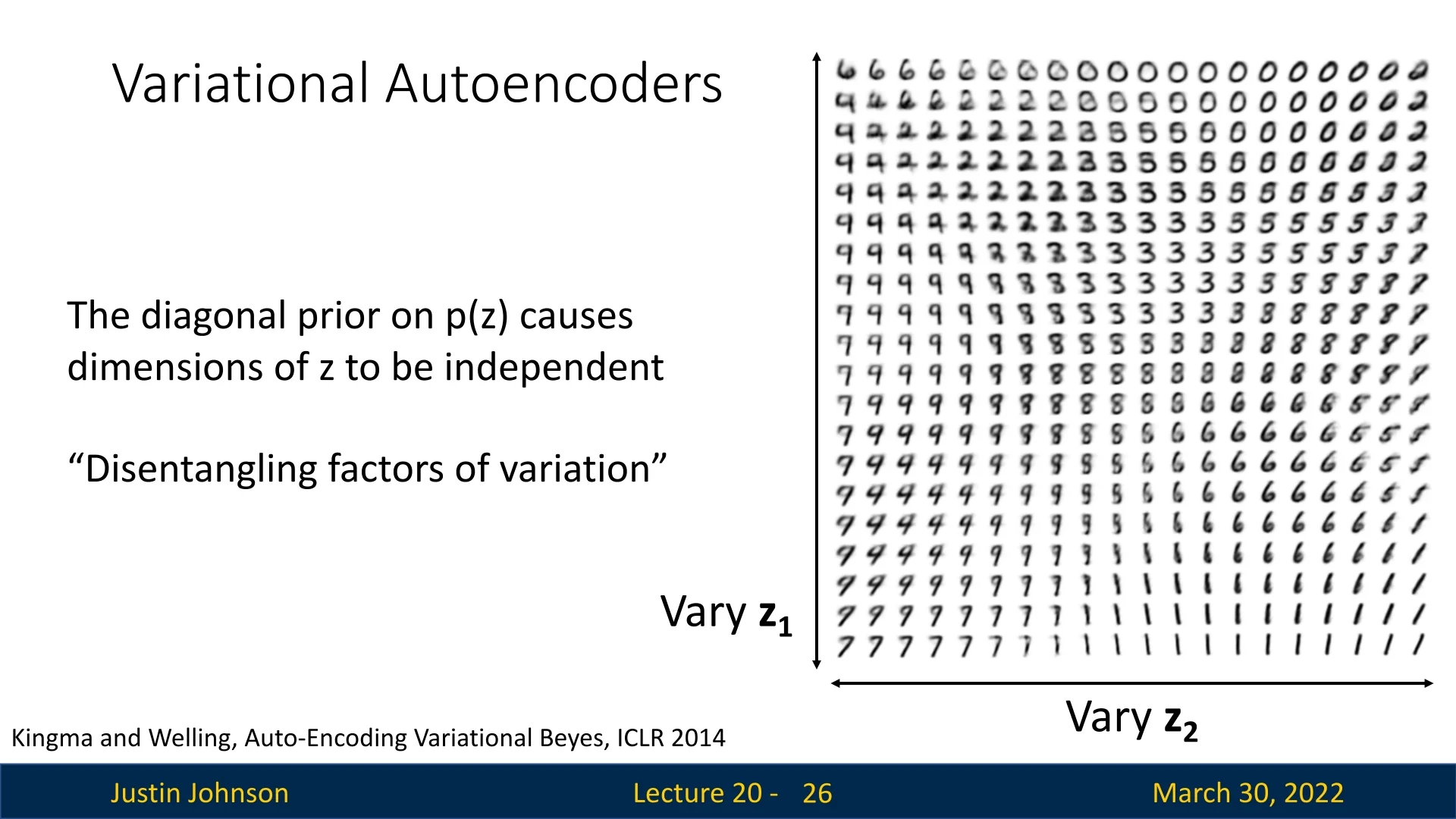

Example 1: MNIST Morphing A classic illustration of this property is provided by [292] using the MNIST dataset of handwritten digits. By training a VAE with a strictly two-dimensional latent space, we can visualize the learned manifold by systematically varying the latent variables \( z_1 \) and \( z_2 \) across a regular grid (using the inverse CDF of the Gaussian to map the grid to probability mass) and decoding the results.

As shown in the below figure, this reveals a highly structured and continuous latent space. Rather than jumping randomly between digits, the decoder produces smooth semantic interpolations:

- Vertical Morphing (\( z_1 \)): Moving along the vertical axis transforms the digit identity smoothly. For instance, we can observe a 6 morphing into a 9, which then transitions into a 7. With slight variations in \( z_2 \), this path may also pass through a region decoding to a 2.

- Horizontal Morphing (\( z_2 \)): Moving along the horizontal axis produces different transitions. In some regions, a 7 gradually straightens into a 1. In others, a 9 thickens into an 8, loops into a 3, and settles back into an 8.

This confirms that the VAE has learned a smooth, continuous manifold where nearby latent codes decode to visually similar images, and linear interpolation in latent space corresponds to meaningful semantic morphing.

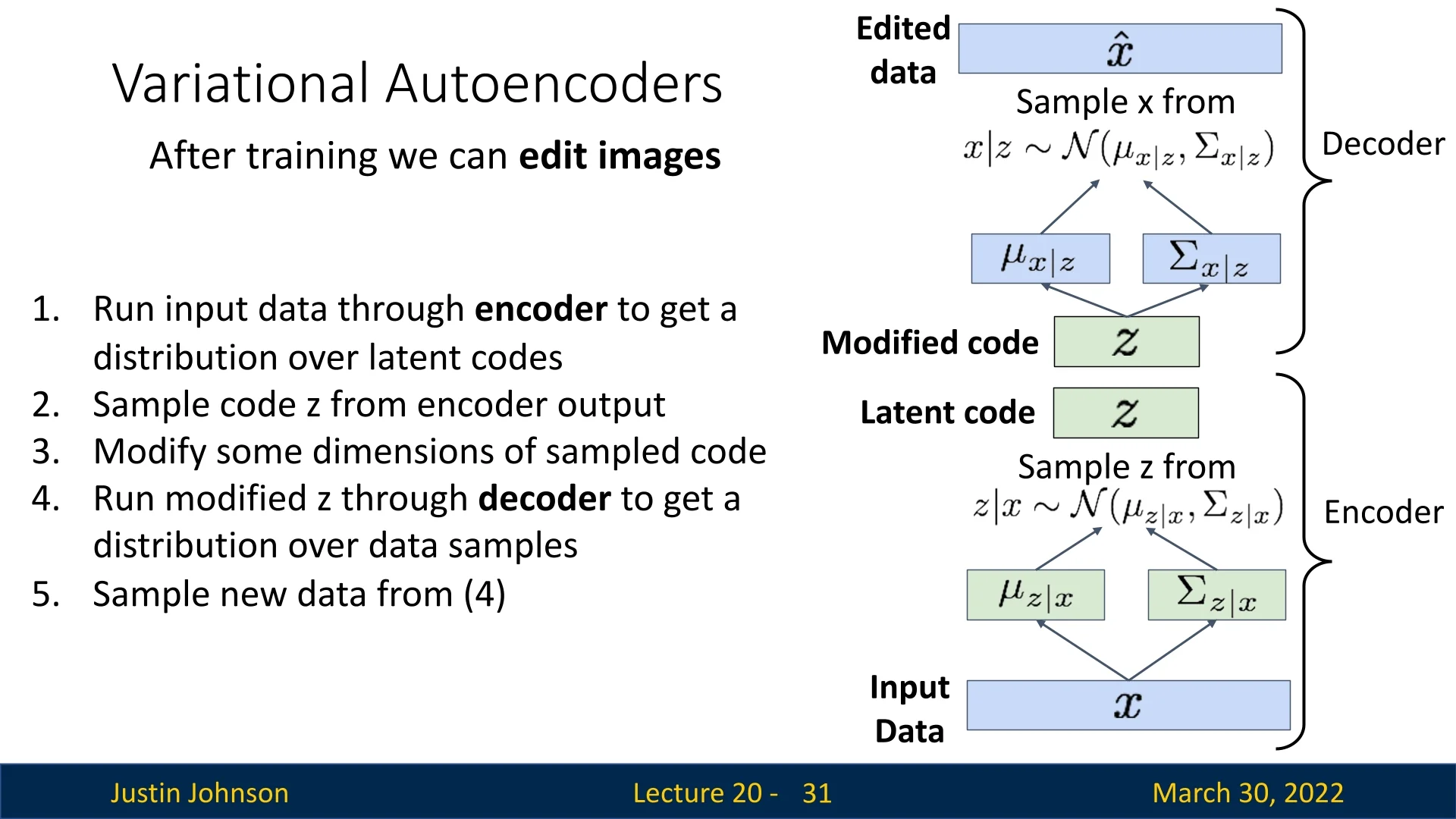

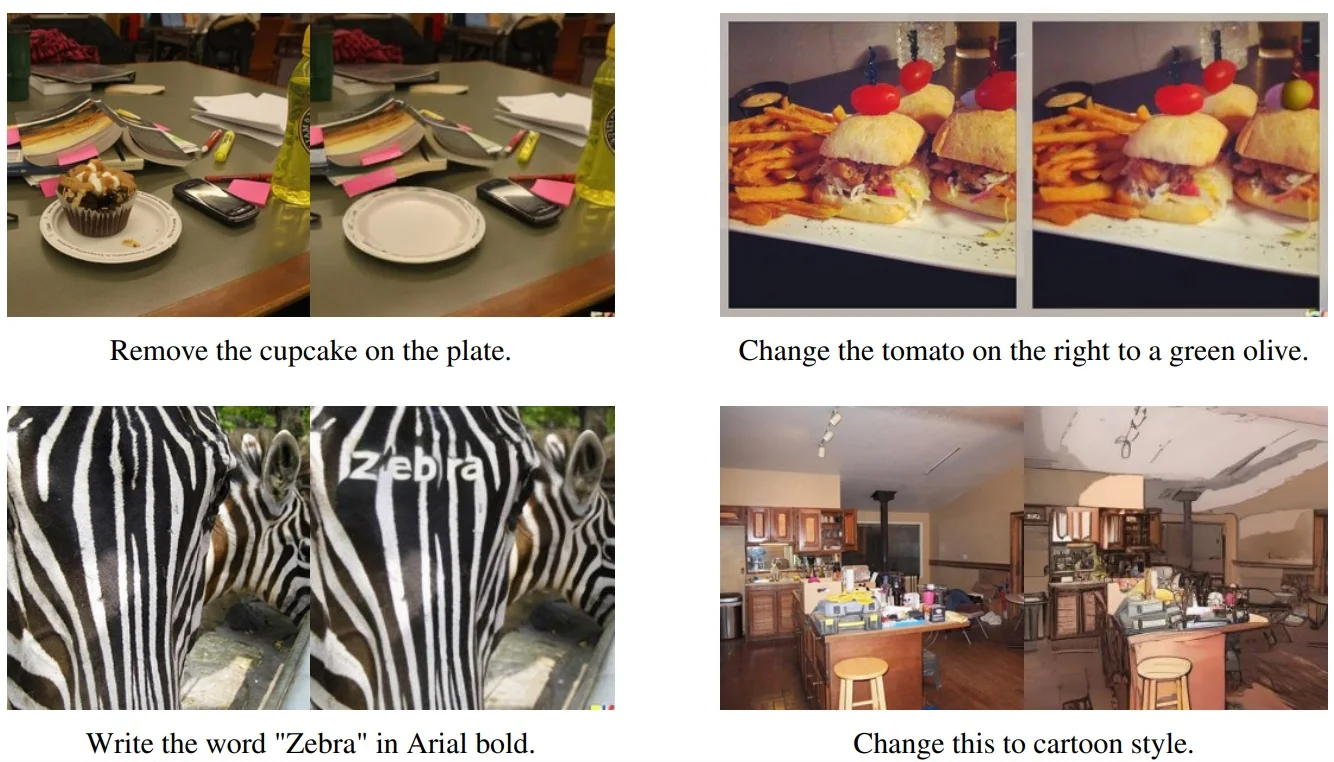

The General Editing Pipeline We can generalize this “traversal” idea into a simple but powerful pipeline for semantic image editing. As illustrated in the below figure, the process is:

- 1.

- Encode: Run the input image \( \mathbf {x} \) through the encoder to obtain the approximate posterior \( q_\phi (\mathbf {z} \mid \mathbf {x}) \).

- 2.

- Sample: Draw a latent code \( \mathbf {z} \sim q_\phi (\mathbf {z} \mid \mathbf {x}) \) using the reparameterization trick from Section 20.1.2.

- 3.

- Edit in latent space: Manually modify one or more coordinates of \( \mathbf {z} \) (for example, set \( \tilde {z}_j = z_j + \delta \)) to obtain a modified code \( \tilde {\mathbf {z}} \).

- 4.

- Decode: Pass the modified code \( \tilde {\mathbf {z}} \) through the decoder \( p_\theta (\mathbf {x} \mid \mathbf {z}) \) to obtain the parameters of an edited-image distribution \( p_\theta (\mathbf {x} \mid \tilde {\mathbf {z}}) \).

- 5.

- Visualize: Either sample \( \hat {\mathbf {x}} \sim p_\theta (\mathbf {x} \mid \tilde {\mathbf {z}}) \) or directly visualize the decoder’s mean as the edited image.

In other words, the encoder maps images to a “control space” (latent codes), we apply simple algebraic edits there, and the decoder renders the results back into image space.

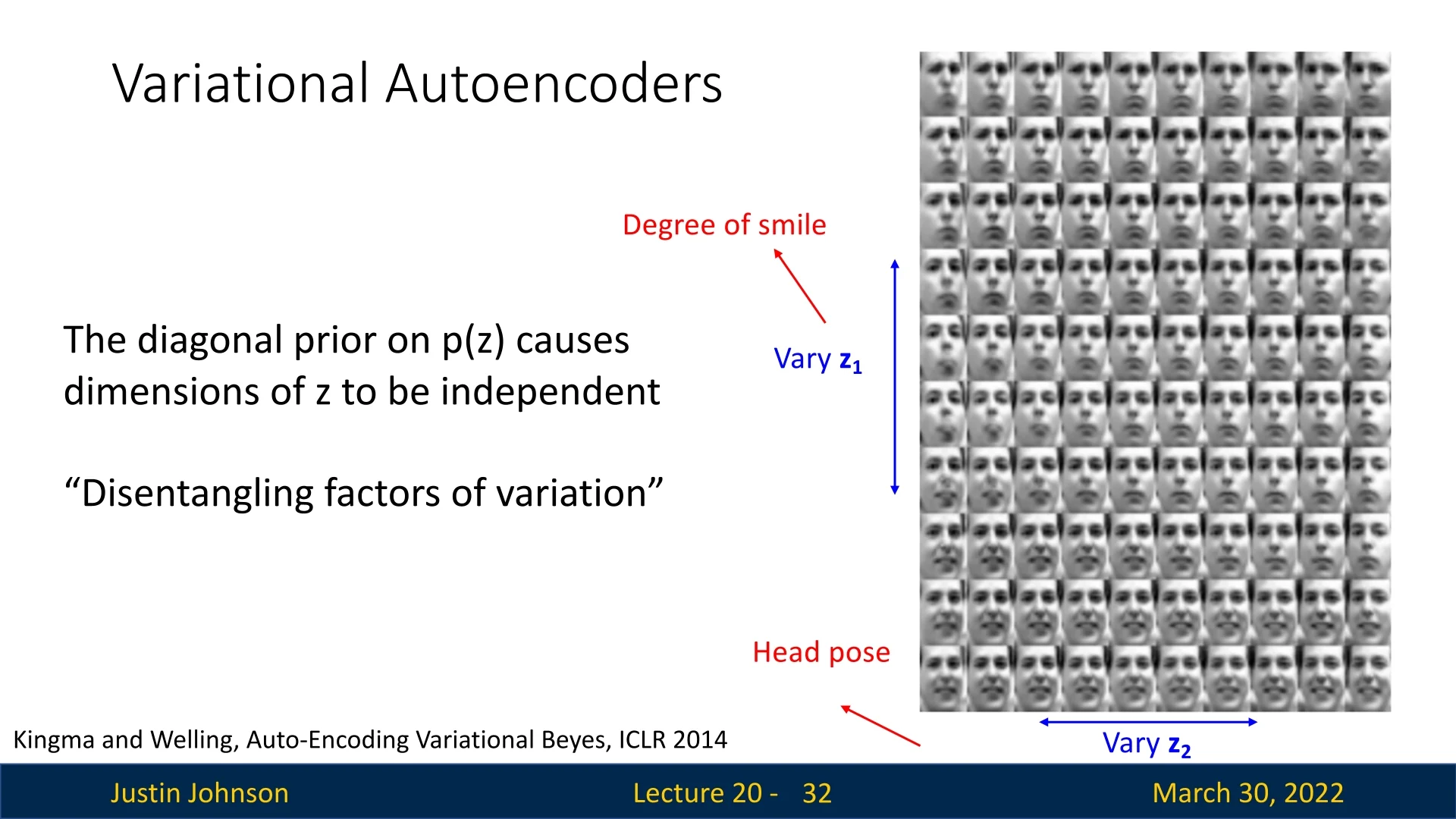

Example 2: Disentanglement in Faces While MNIST mainly exhibits simple geometric morphing, VAEs applied to more complex data often uncover high-level semantic attributes. This phenomenon is known as disentanglement: particular dimensions of \( \mathbf {z} \) align with individual generative factors.

In the original VAE paper [292], the authors demonstrated this on the Frey Face dataset. Even without label supervision, the model discovered latent coordinates that separately control expression and pose:

- Varying one latent coordinate continuously changes the degree of smiling.

- Varying another coordinate continuously changes the head pose.

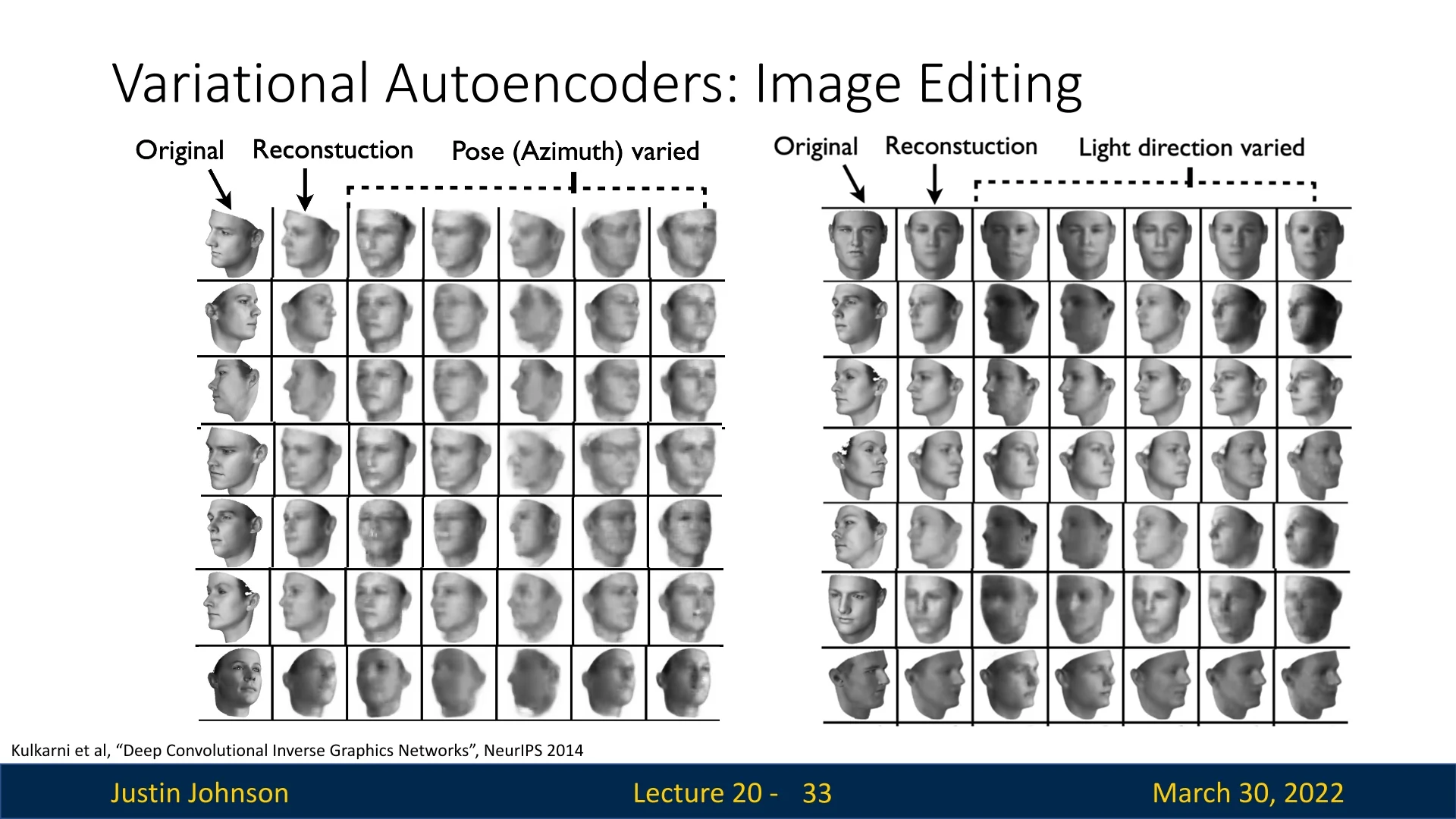

This capability was further refined by [308] in the Deep Convolutional Inverse Graphics Network (DC-IGN). Training on 3D-rendered faces, they identified specific latent variables that act like “knobs” in a graphics engine:

- Pose (azimuth): rotating the head around the vertical axis while preserving identity.

- Lighting: moving the light source around the subject, while keeping pose fixed.

As shown in the following figure, editing a single latent value can rotate a face in 3D or sweep the illumination direction, indicating that the model has captured underlying 3D structure from 2D pixels.

These examples highlight a key qualitative advantage of VAEs: beyond modeling the data distribution, they expose a low-dimensional latent space in which many generative factors can be probed, interpolated, and edited. In practice, disentanglement is imperfect and not guaranteed, but even partially disentangled latents already enable powerful and interpretable control over generated images.

Takeaway Unlike autoregressive models (e.g., PixelCNN) that only model \(p(\mathbf {x})\) directly and provide no explicit latent code, VAEs learn a structured latent representation \( \mathbf {z} \). This representation can be used to interpolate between images, explore variations along semantic directions, and perform targeted edits, making VAEs particularly valuable for representation learning and controllable generation.

20.3 Summary & Examples: Variational Autoencoders

Variational Autoencoders (VAEs) introduce a probabilistic framework on top of the traditional autoencoder architecture. Instead of learning a deterministic mapping, they:

- treat the latent code \( \mathbf {z} \) as a random variable drawn from an encoder-predicted posterior \( q_\phi (\mathbf {z} \mid \mathbf {x}) \),

- model the data generation process via a conditional likelihood \( p_\theta (\mathbf {x} \mid \mathbf {z}) \),

- and optimize the Evidence Lower Bound (ELBO) instead of the intractable marginal likelihood \( p_\theta (\mathbf {x}) \).

- Principled formulation: VAEs are grounded in Bayesian inference and variational methods, giving a clear probabilistic interpretation of both training and inference.

- Amortized inference: The encoder \( q_\phi (\mathbf {z} \mid \mathbf {x}) \) allows fast, single-pass inference of latent codes for new data, which can be reused for downstream tasks such as classification, clustering, or editing.

- Interpretable latent space: As seen in the traversals above, the latent space often captures semantic factors (pose, light, expression) in a smooth, continuous manifold.

- Fast sampling: Generating new data is efficient: sample \( \mathbf {z} \sim \mathcal {N}(\mathbf {0}, \mathbf {I}) \) and decode once.

- Approximation gap: VAEs maximize a lower bound (ELBO), not the exact log-likelihood. If the approximate posterior \( q_\phi (\mathbf {z} \mid \mathbf {x}) \) is too restricted (for example, diagonal Gaussian), the model may underfit and assign suboptimal likelihood to the data.

- Blurry samples: With simple factorized Gaussian decoders (and the associated MSE-like reconstruction loss), VAEs tend to produce over-smoothed images that lack the sharp, high-frequency details achieved by PixelCNNs, GANs, or diffusion models.

Active Research Directions Research on VAEs often focuses on mitigating these downsides while preserving their strengths:

- Richer posteriors: Replacing the diagonal Gaussian \( q_\phi (\mathbf {z} \mid \mathbf {x}) \) with more flexible families such as normalizing flows or autoregressive networks to reduce the ELBO gap.

- Structured priors: Using hierarchical or discrete/categorical priors and structured latent spaces to better capture factors of variation and induce disentanglement.

- Hybrid models: Combining VAEs with autoregressive decoders (e.g., PixelVAE), so that the global structure is captured by \( \mathbf {z} \) while local detail is modeled autoregressively.

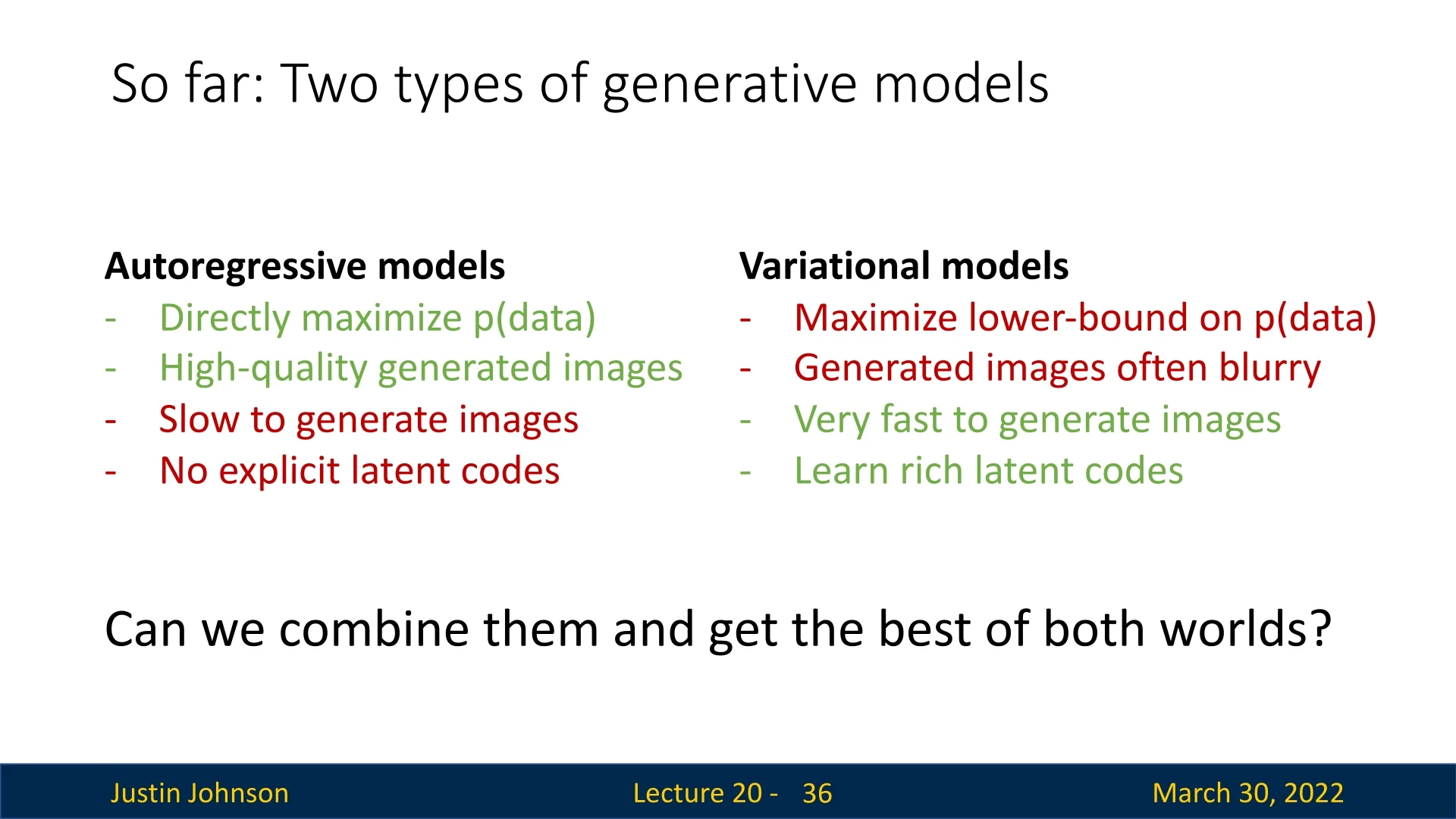

Comparison: Autoregressive vs. Variational Throughout this chapter, we have contrasted two major families of generative models. Figure 20.9 summarizes the trade-offs:

-

Autoregressive models (PixelRNN / PixelCNN):

- Directly maximize \( p_\theta (\mathbf {x}) \) with exact likelihood.

- Produce sharp, high-quality images.

- Are typically slow to sample from, since pixels are generated sequentially.

- Do not expose an explicit low-dimensional latent code.

-

Variational models (VAEs):

- Maximize a lower bound on \( p_\theta (\mathbf {x}) \) rather than the exact likelihood.

- Often produce smoother (blurrier) images with simple decoders.

- Are very fast to sample from once trained.

- Learn rich, editable latent codes that support interpolation and semantic control.

This comparison naturally raises the next question we will address: Can we combine these approaches and obtain the best of both worlds?

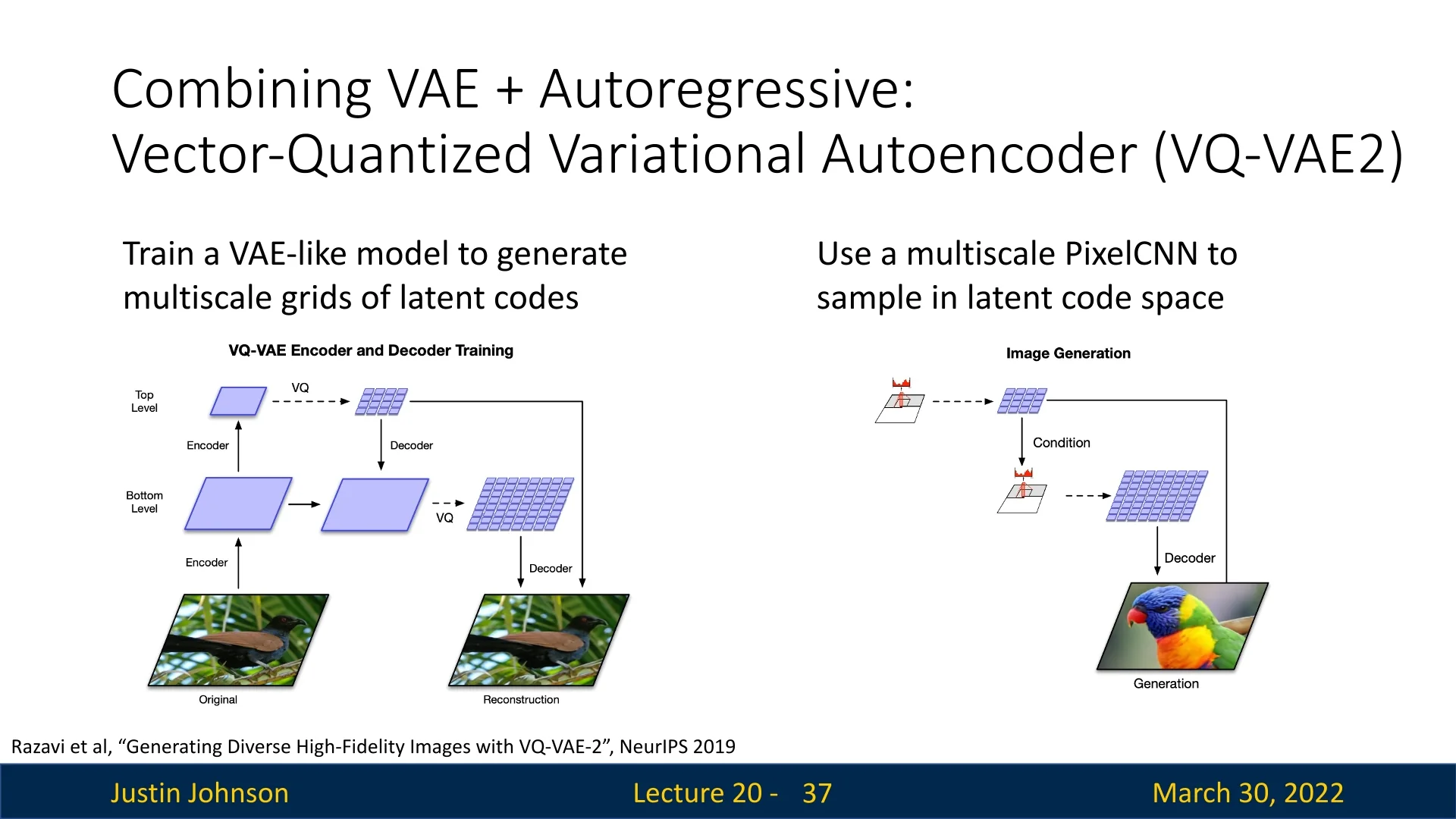

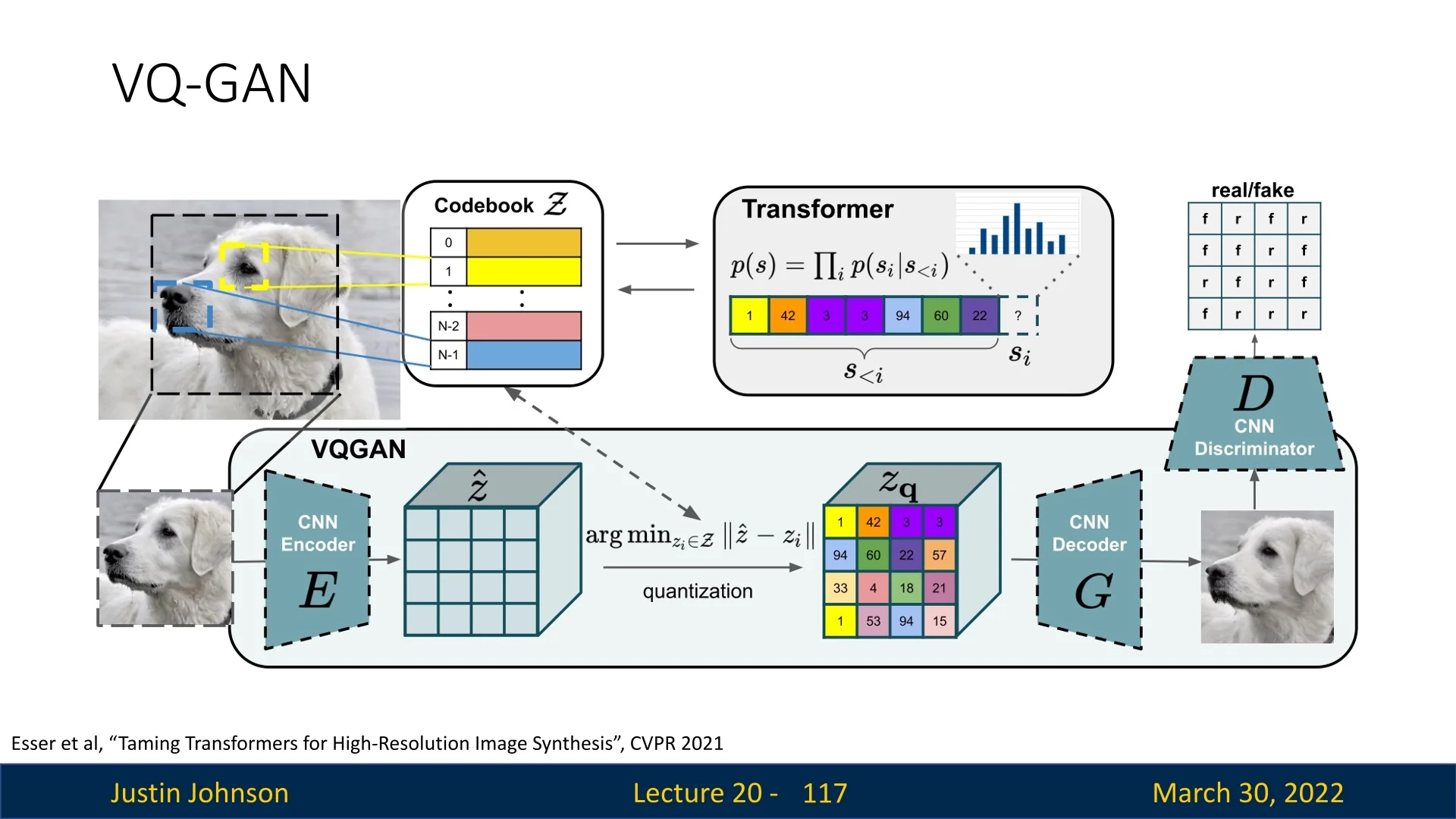

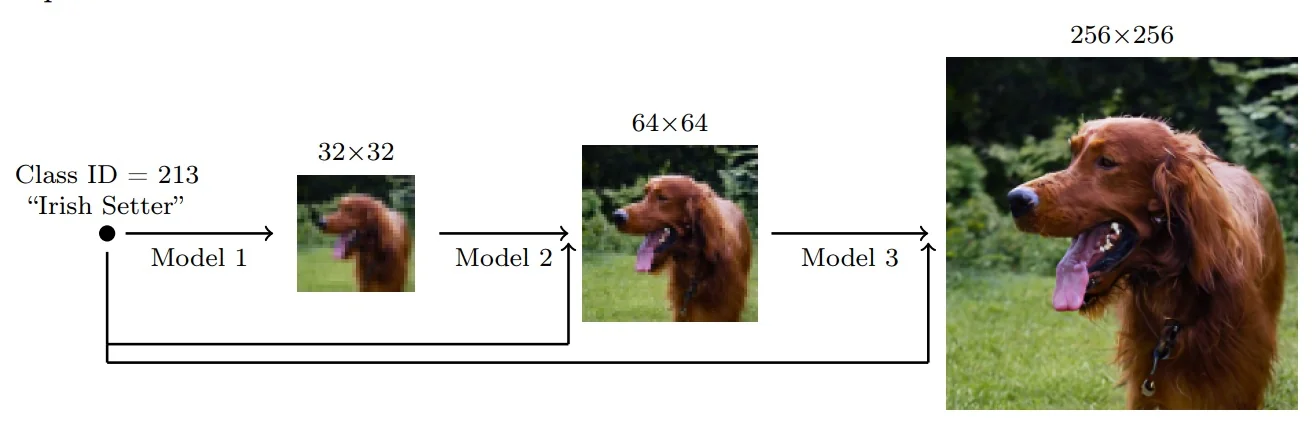

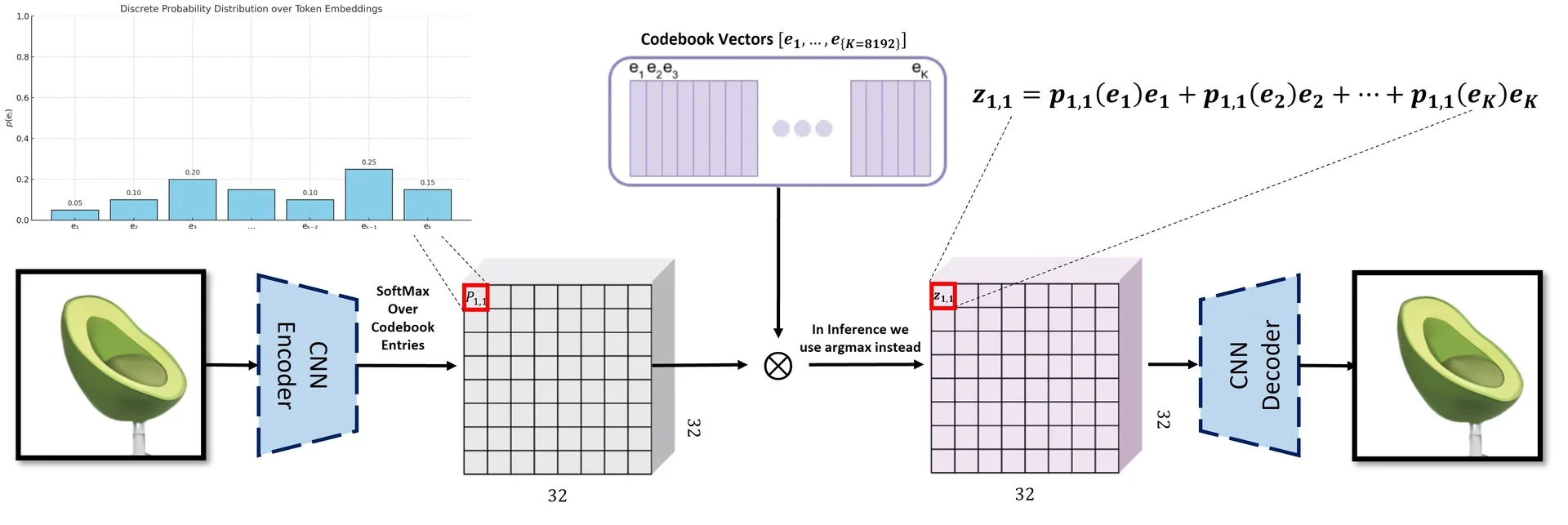

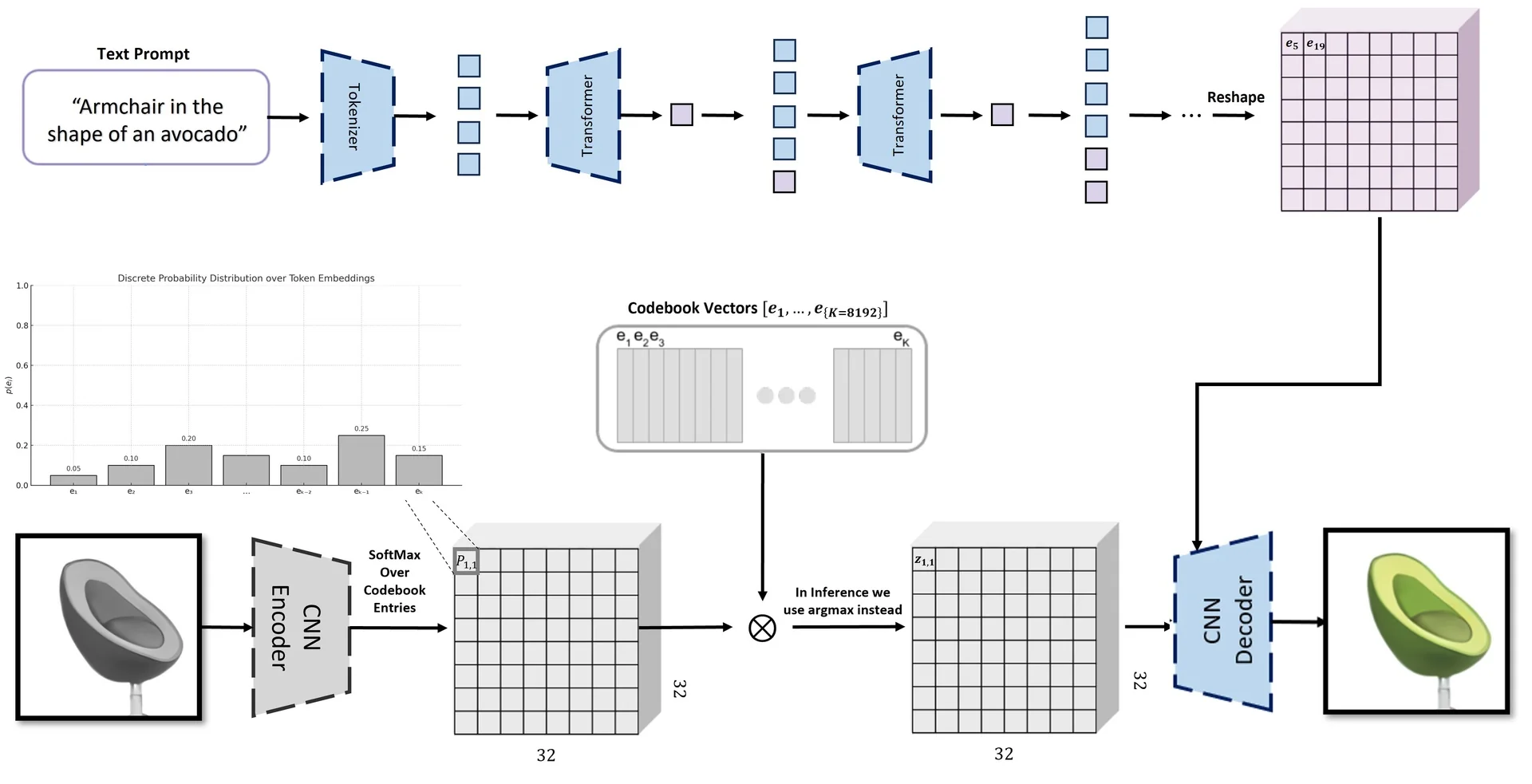

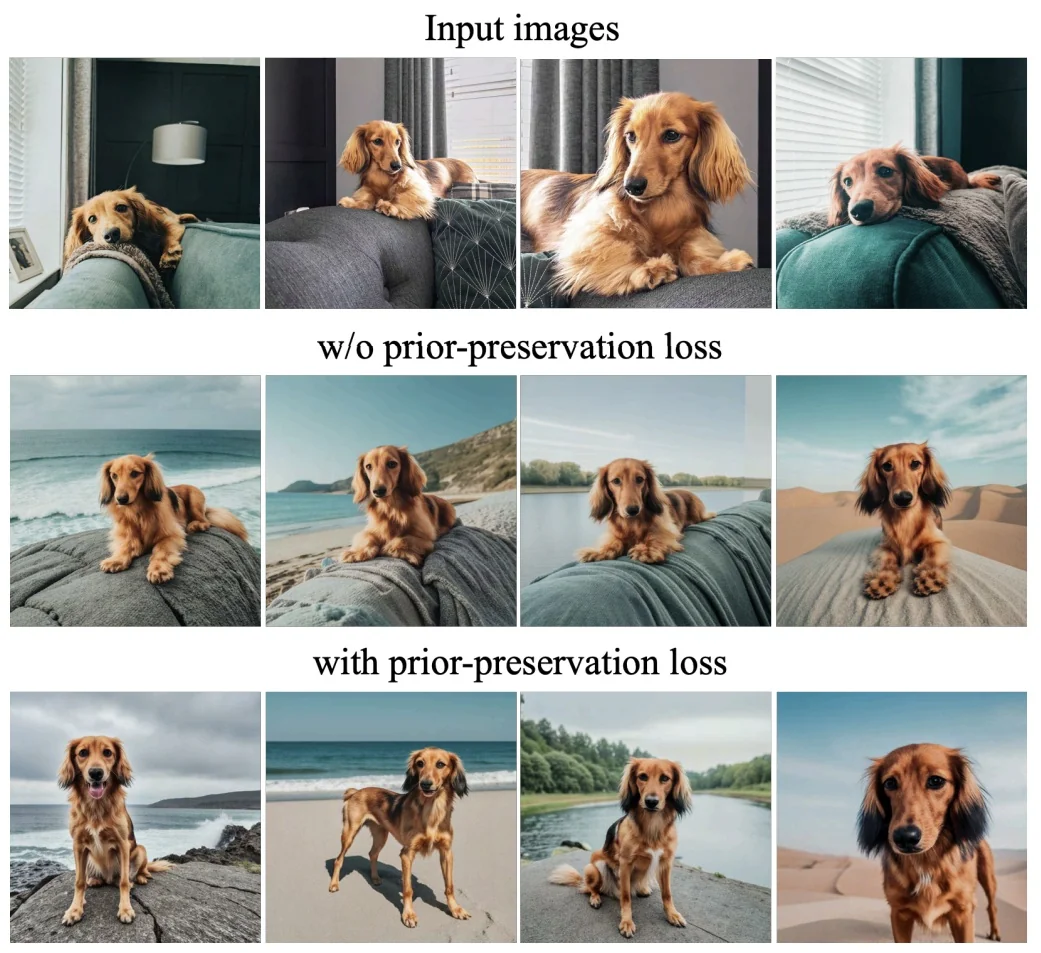

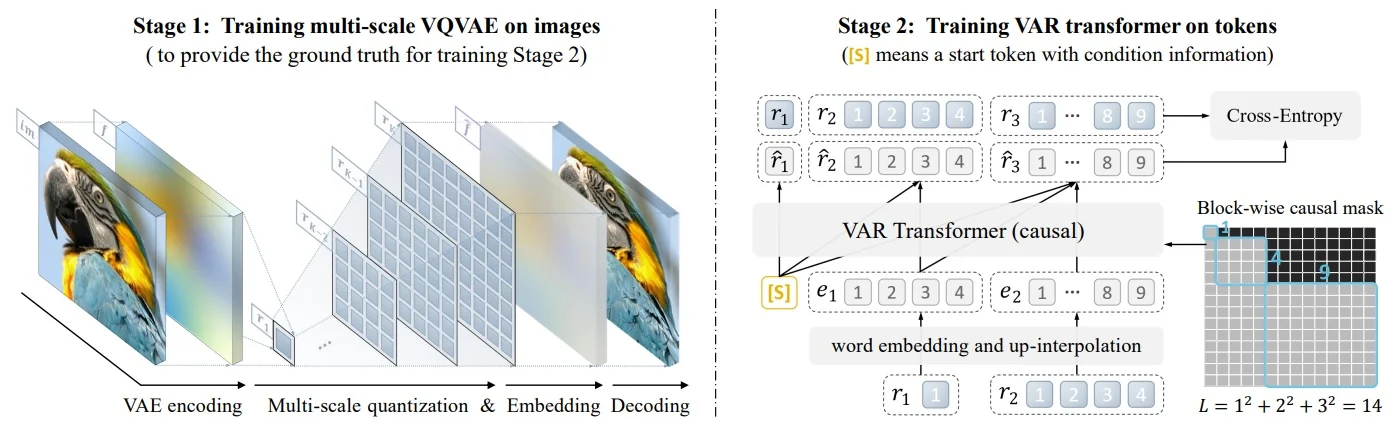

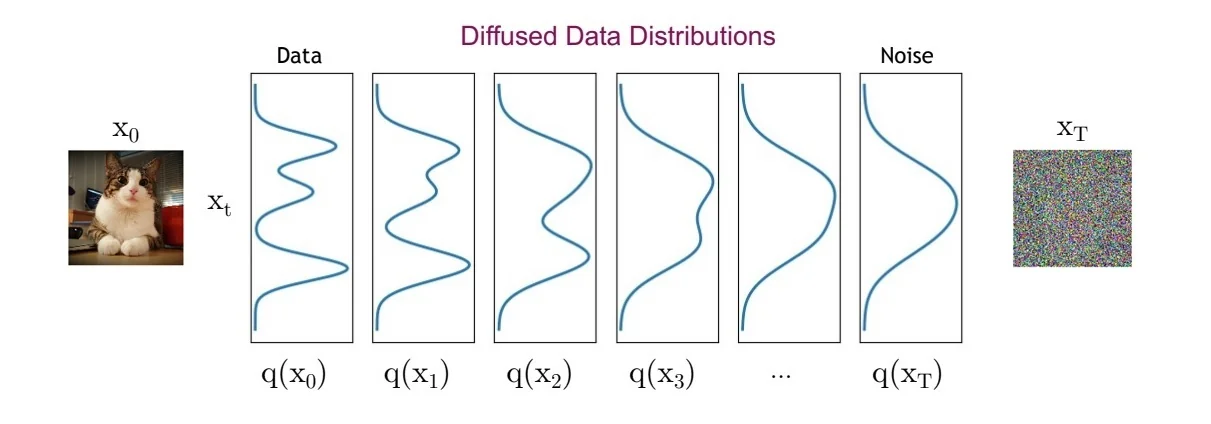

20.3.1 VQ-VAE-2: Combining VAEs with Autoregressive Models

Motivation Variational Autoencoders (VAEs) offer a principled latent variable framework for generative modeling, but their outputs often lack detail due to oversimplified priors and decoders. In contrast, autoregressive models such as PixelCNN produce sharp images by modeling pixel-level dependencies but lack interpretable latent variables and are slow to sample from.

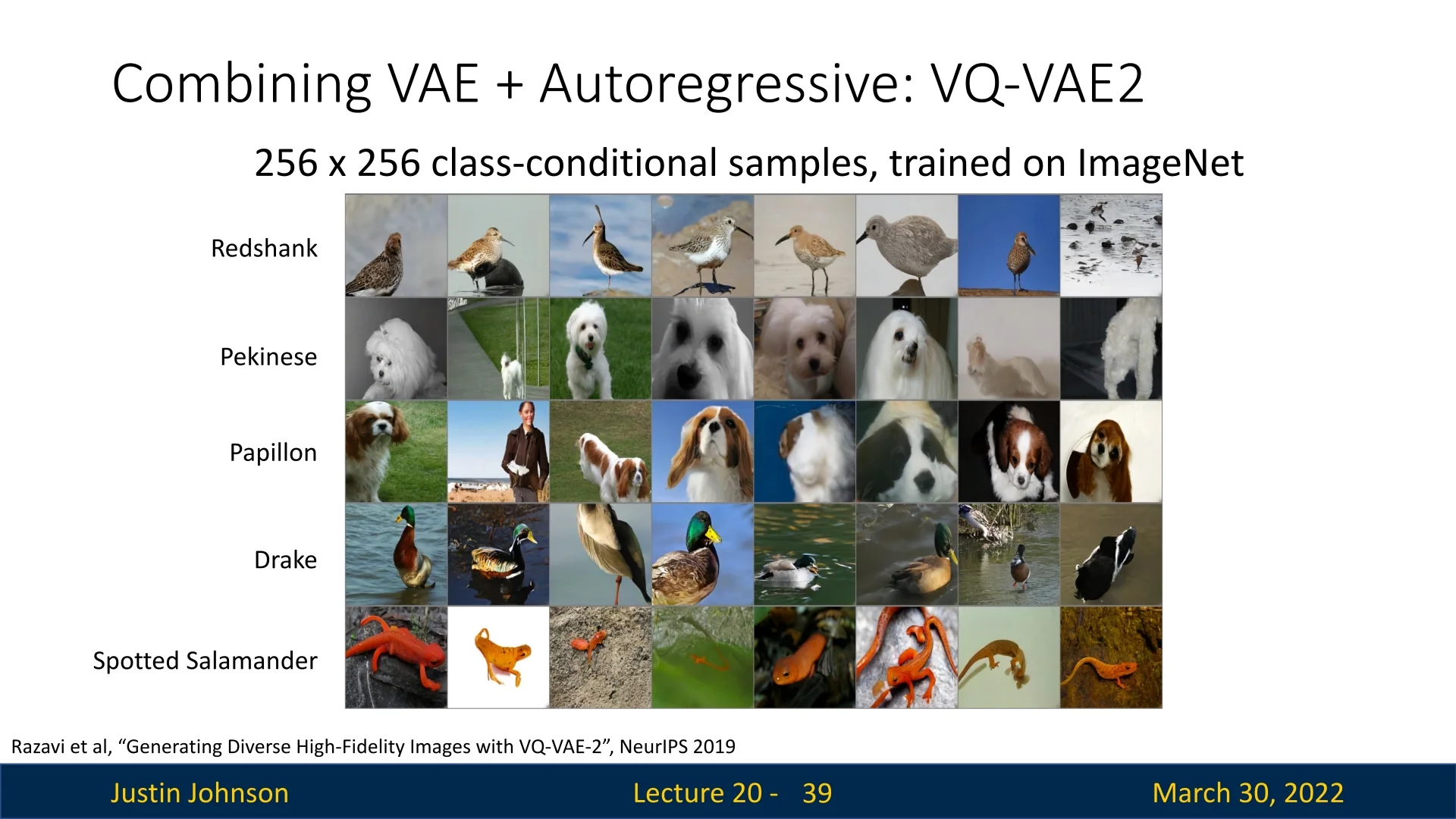

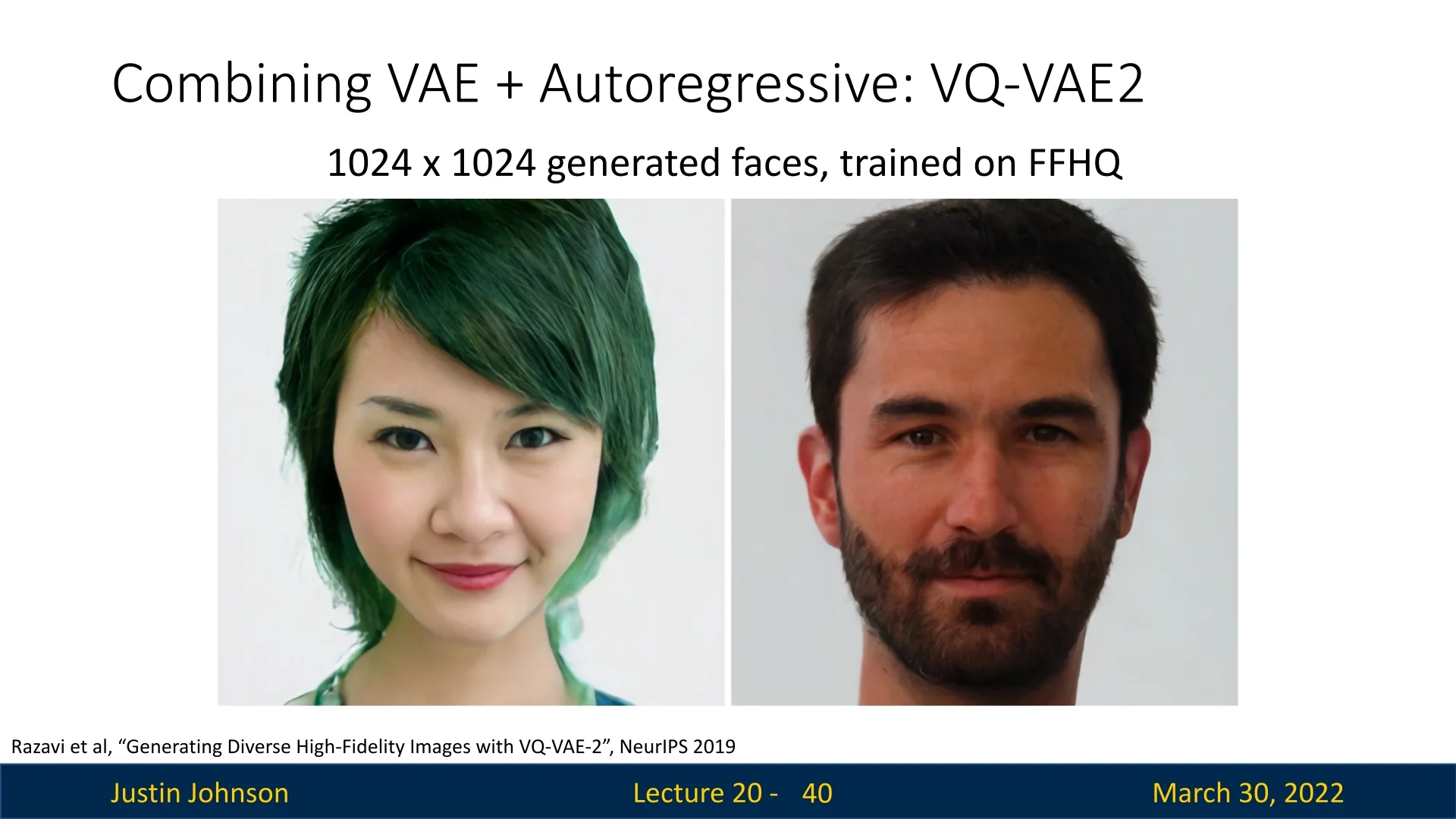

VQ-VAE-2 [514] combines these paradigms: it learns discrete latent representations via vector quantization (as in VQ-VAE), and models their distribution using powerful autoregressive priors. This approach achieves both high-fidelity synthesis and efficient, structured latent codes.

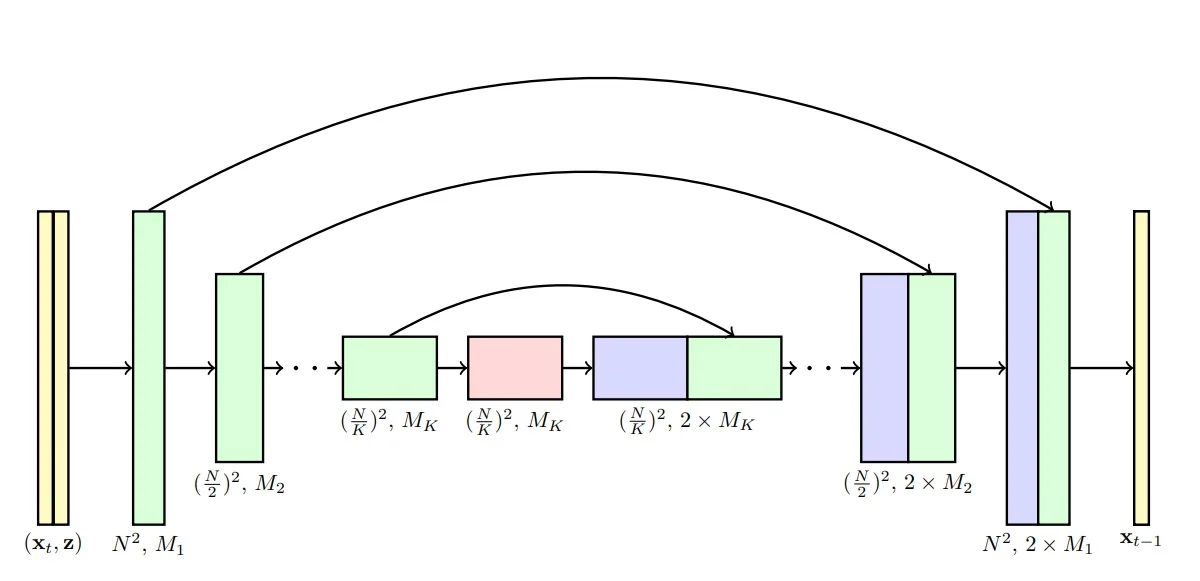

Architecture Overview VQ-VAE-2 introduces a powerful combination of hierarchical encoding, discrete latent representations, and autoregressive priors. At its core, it improves upon traditional VAEs by replacing continuous latent variables with discrete codes through a process called vector quantization.

-

Hierarchical Multi-Level Encoder:

The input image \( \mathbf {x} \in \mathbb {R}^{H \times W \times C} \) is passed through two stages of convolutional encoders:

- A bottom-level encoder extracts a latent feature map \( \mathbf {z}_b^e \in \mathbb {R}^{H_b \times W_b \times d} \), where \( H_b < H \), \( W_b < W \). This captures low-level image details (e.g., textures, edges).

- A top-level encoder is then applied to \( \mathbf {z}_b^e \), producing \( \mathbf {z}_t^e \in \mathbb {R}^{H_t \times W_t \times d} \), with \( H_t < H_b \), \( W_t < W_b \). This higher-level map captures global semantic information (e.g., layout, object presence).

The spatial resolution decreases at each stage due to strided convolutions, forming a coarse-to-fine hierarchy of latent maps.

-

Vector Quantization and Codebooks:

Rather than passing the encoder outputs directly to the decoder, each position in the latent maps is replaced by its closest vector from a learned codebook.

Intuition: Think of the codebook as a fixed “dictionary” of feature prototypes. Just as we approximate a sentence using a limited vocabulary of words, VQ-VAE approximates an image using a limited vocabulary of learnable feature vectors.

Each codebook is a set of \( K \) discrete embedding vectors: \[ \mathcal {C} = \{ \mathbf {e}_k \in \mathbb {R}^d \}_{k=1}^K \] Quantization proceeds by computing, for each latent vector \( \mathbf {z}_e(i, j) \), its nearest codebook entry: \[ \mathbf {z}_q(i,j) = \mathbf {e}_{k^\star }, \quad \mbox{where } k^\star = \operatorname *{argmin}_{k} \| \mathbf {z}_e(i,j) - \mathbf {e}_k \|_2 \]

This process converts the encoder output \( \mathbf {z}_e \in \mathbb {R}^{H_l \times W_l \times d} \) (for each level \( l \in \{b, t\} \)) into a quantized tensor \( \mathbf {z}_q \in \mathbb {R}^{H_l \times W_l \times d} \), and a corresponding index map: \[ \mathbf {i}_l \in \{1, \dots , K\}^{H_l \times W_l} \] The quantized representation consists of the code vectors \( \mathbf {z}_l^q(i,j) = \mathcal {C}^{(l)}[\mathbf {i}_l(i,j)] \).

Why this matters:

- It creates a discrete latent space with symbolic representations and structured reuse of learned patterns.

- Discretization acts as a form of regularization, preventing the encoder outputs from drifting.

- Why not use continuous embeddings? In continuous VAEs, the model often “cheats” by hiding microscopic details in the infinite precision of the latent vector. Discretization forces the model to keep only the essential feature prototypes.

- Most importantly, it enables the use of autoregressive priors (PixelCNN) that model the distribution over discrete indices. These models are exceptionally good at predicting discrete tokens (like words in a language model) but struggle to model complex continuous distributions.

-

Shared Decoder (Coarse-to-Fine Reconstruction):

The quantized latents from both levels are passed to a shared decoder:

- The top-level quantized embedding map \( \mathbf {z}_t^q \in \mathbb {R}^{H_t \times W_t \times d} \) is first decoded into a coarse semantic feature map.

- The bottom-level quantized embedding \( \mathbf {z}_b^q \in \mathbb {R}^{H_b \times W_b \times d} \) is then decoded conditioned on the top-level output.

This coarse-to-fine strategy improves reconstruction quality and allows the decoder to combine semantic context with fine detail.

-

Autoregressive Priors (Trained After Autoencoder):

Once the VQ-VAE-2 autoencoder (i.e., encoders, decoder, and codebooks) has been trained to reconstruct images, we introduce two PixelCNN-based autoregressive priors to enable data generation from scratch.

These models operate over the discrete index maps produced during quantization:

- \( \mbox{PixelCNN}_t \) models the unconditional prior \( p(\mathbf {i}_t) \), i.e., the joint distribution over top-level latent indices. It is trained autoregressively in raster scan order over the 2D grid \( H_t \times W_t \).

- \( \mbox{PixelCNN}_b \) models the conditional prior \( p(\mathbf {i}_b \mid \mathbf {i}_t) \), i.e., the distribution of bottom-level code indices given the sampled top-level indices. It is also autoregressive over the spatial positions \( H_b \times W_b \), but each prediction is conditioned on both previous bottom-level indices and the entire top-level map \( \mathbf {i}_t \).

Choice of Autoregressive Prior: PixelCNN vs. PixelRNN/LSTMs

While the VQ-VAE-2 architecture uses PixelCNN, other autoregressive sequence models exist. It is important to understand the trade-offs that motivate this choice:

- Recurrent Models (PixelRNN, Diagonal BiLSTM): RNN-based approaches, such as PixelRNN (which includes Row LSTM and Diagonal BiLSTM variants), are valid autoregressive models. Because they rely on recurrent hidden states, they theoretically have an infinite receptive field and can model complex long-range dependencies effectively.

- Why PixelCNN is preferred: Despite the theoretical power of LSTMs, they are inherently sequential—computing pixel \(t\) requires the hidden state from \(t-1\). This makes training slow and difficult to parallelize over large 2D grids. In contrast, PixelCNN uses masked convolutions. This allows the model to compute the probability of all indices in the map simultaneously during training (parallelization), offering a crucial speed and scalability advantage for the high-resolution hierarchical maps in VQ-VAE-2.

Note on Dimensions: The PixelCNN does not input the high-dimensional VQ vectors (e.g., size 64). It inputs the indices (integers). Internally, the PixelCNN learns its own separate, smaller embeddings optimized for sequence prediction.

How does autoregressive sampling begin? PixelCNN models generate a grid of indices one element at a time, using a predefined order (e.g., row-major order). To start the generation process:

- The first pixel (i.e., top-left index \( \mathbf {i}_t(1,1) \)) is sampled from a learned marginal distribution (or initialized with a zero-padding context).

- Subsequent pixels are sampled conditioned on all previously generated values (e.g., \( \mathbf {i}_t(1,2) \sim p(i_{1,2} \mid i_{1,1}) \), and so on).

This sampling continues until all elements of \( \mathbf {i}_t \) and \( \mathbf {i}_b \) are filled in.

How does this enable generation? Once we have sampled both latent index maps:

- 1.

- Retrieve the quantized embeddings \( \mathbf {z}_t^q = \mathcal {C}^{(t)}[\mathbf {i}_t] \) and \( \mathbf {z}_b^q = \mathcal {C}^{(b)}[\mathbf {i}_b] \).

- 2.

- Feed both into the trained decoder: \( \hat {\mathbf {x}} = \mbox{Decoder}(\mathbf {z}_t^q, \mathbf {z}_b^q) \).

This approach allows us to sample novel images with global coherence (via top-level modeling) and local realism (via bottom-level refinement), while reusing the learned latent structure of the VQ-VAE-2 encoder-decoder pipeline.

Summary Table: Dimensional Flow and Index Usage

| Stage | Tensor Shape | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Input Image \( \mathbf {x} \) | \( H \times W \times C \) | Original RGB (or grayscale) image given as input to the VQ-VAE-2 pipeline. |

| Bottom Encoder Output \( \mathbf {z}_b^e \) | \( H_b \times W_b \times d \) | Bottom-level continuous latent map produced by the first encoder. Captures fine-scale features. |

| Top Encoder Output \( \mathbf {z}_t^e \) | \( H_t \times W_t \times d \) | Top-level continuous latent map obtained by passing \( \mathbf {z}_b^e \) through the second encoder. Captures high-level, coarse information. |

| Top-Level Index Map \( \mathbf {i}_t \) | \( H_t \times W_t \) | At each spatial location \( (i,j) \), stores index of the nearest codebook vector in \( \mathcal {C}^{(t)} \) for \( \mathbf {z}_t^e(i,j) \). |

| Bottom-Level Index Map \( \mathbf {i}_b \) | \( H_b \times W_b \) | At each spatial location \( (i,j) \), stores index of the nearest codebook vector in \( \mathcal {C}^{(b)} \) for \( \mathbf {z}_b^e(i,j) \). |

| Quantized Top-Level \( \mathbf {z}_t^q \) | \( H_t \times W_t \times d \) | Latent tensor constructed by replacing each feature in \( \mathbf {z}_t^e \) with the corresponding codebook vector from \( \mathcal {C}^{(t)} \) using \( \mathbf {i}_t \). |

| Quantized Bottom-Level \( \mathbf {z}_b^q \) | \( H_b \times W_b \times d \) | Latent tensor constructed by replacing each feature in \( \mathbf {z}_b^e \) with the corresponding codebook vector from \( \mathcal {C}^{(b)} \) using \( \mathbf {i}_b \). |

| Reconstructed Image \( \hat {\mathbf {x}} \) | \( H \times W \times C \) | Final decoded image produced by feeding \( \mathbf {z}_t^q \) and \( \mathbf {z}_b^q \) into the decoder in a coarse-to-fine manner. |

Next: Training and Inference Flow Now that the architecture is defined, we proceed to describe the full training process. This includes:

- The VQ-VAE loss decomposition: reconstruction, codebook, and commitment losses.

- How gradients flow with the use of the stop-gradient operator.

- Post-hoc training of PixelCNNs over discrete index maps.

- Image generation during inference: sampling \( \mathbf {i}_t \rightarrow \mathbf {i}_b \rightarrow \hat {\mathbf {x}} \).

Training the VQ-VAE-2 Autoencoder

Objective Overview The VQ-VAE-2 model is trained to reconstruct input images while simultaneously learning a meaningful discrete latent space. Its objective function is composed of three terms:

\[ \mathcal {L}_{\mbox{VQ-VAE-2}} = \underbrace {\mathcal {L}_{\mbox{recon}}}_{\mbox{Image Fidelity}} + \underbrace {\mathcal {L}_{\mbox{codebook}}}_{\mbox{Codebook Update}} + \underbrace {\beta \cdot \mathcal {L}_{\mbox{commit}}}_{\mbox{Encoder Regularization}} \]

Each term serves a different purpose in enabling a stable and effective quantized autoencoder. We now explain each one.

1. Reconstruction Loss (\( \mathcal {L}_{\mbox{recon}} \)) This term encourages the decoder to faithfully reconstruct the input image from the quantized latent codes: \[ \mathcal {L}_{\mbox{recon}} = \| \mathbf {x} - \hat {\mathbf {x}} \|_2^2 \] Here, \( \hat {\mathbf {x}} = D(\mathbf {z}_t^q, \mathbf {z}_b^q) \) is the image reconstructed from the quantized top and bottom latent maps. This is a pixel-wise squared error (or optionally a negative log-likelihood if modeling pixels probabilistically).

Why is the reconstruction sometimes blurry? The use of \( L_2 \) loss (Mean Squared Error) mathematically forces the model to predict the mean (average) of all plausible pixel values.

- Example: If the model is unsure whether an edge should be black (0) or white (255), the “safest” prediction to minimize \( L_2 \) error is gray (127). This averaging creates blur.

- L1 vs L2: While \( L_1 \) loss forces the model to predict the median (which can be slightly sharper/less sensitive to outliers), it still fundamentally penalizes pixel-level differences rather than perceptual realism.

- Solution: To fix this, modern successors (like VQ-GAN) add an Adversarial Loss, which penalizes the model if the texture looks “fake” or blurry, regardless of the pixel math.

2. Codebook Update (\( \mathcal {L}_{\mbox{codebook}} \)) In VQ-VAE, the encoder produces a continuous latent vector at each spatial location, but the model then quantizes this vector to the nearest entry in a learned codebook. Let \[ \mathbf {z}_e(i,j) \in \mathbb {R}^d \quad \mbox{and}\quad \mathcal {C} = \{\mathbf {e}_k\}_{k=1}^{K},\ \mathbf {e}_k \in \mathbb {R}^d \] denote the encoder output and a codebook of \(K\) embeddings, respectively. Quantization selects a discrete index via a nearest-neighbor lookup: \[ k^\star (i,j) \;=\; \operatorname *{argmin}_{k \in \{1,\dots ,K\}} \left \| \mathbf {z}_e(i,j) - \mathbf {e}_k \right \|_2, \qquad \mathbf {z}_q(i,j) \;=\; \mathbf {e}_{k^\star (i,j)}. \]

Why non-differentiability matters. The mapping \(\mathbf {z}_e \mapsto k^\star \) involves an \(\operatorname *{argmin}\) over discrete indices, which is non-differentiable: infinitesimal changes in \(\mathbf {z}_e\) typically do not change the selected index \(k^\star \). Consequently, standard backpropagation cannot propagate gradients through the index selection to instruct the encoder on how to adjust \(\mathbf {z}_e\).

VQ-VAE resolves this by decoupling the updates:

- For the Encoder: It uses a straight-through gradient estimator, effectively copying gradients from the decoder input \(\mathbf {z}_q\) directly to the encoder output \(\mathbf {z}_e\) during the backward pass (treating quantization as an identity map for gradients).

- For the Codebook: It uses a separate update rule to explicitly move the embedding vectors \(\mathbf {e}_k\) toward the encoder outputs that selected them.

There are two standard strategies to implement this codebook update: a gradient-based objective (from the original VQ-VAE) and an EMA-based update (a commonly used stable alternative).

(a) Gradient-Based Codebook Loss (Original VQ-VAE) In this approach, the codebook embeddings are optimized by minimizing the squared distance between each selected embedding and the corresponding encoder output. Crucially, we stop gradients flowing into the encoder for this term so that it updates only the codebook: \begin {equation} \mathcal {L}_{\mbox{codebook}} = \left \| \texttt{sg}[\mathbf {z}_e(i,j)] - \mathbf {e}_{k^\star (i,j)} \right \|_2^2. \label {eq:chapter20_vqvae_codebook_loss} \end {equation}

Here \(\texttt{sg}[\cdot ]\) denotes the stop-gradient operator. This treats \(\mathbf {z}_e\) as a constant constant, ensuring that:

- \(\mathcal {L}_{\mbox{codebook}}\) pulls the code \(\mathbf {e}_{k^\star }\) toward the data point \(\mathbf {z}_e\) (a prototype update).

- The encoder is not pulled toward the codebook by this loss, preventing the two from ”chasing” each other unstably.

To prevents the encoder outputs from drifting arbitrarily far from the codebook, VQ-VAE requires a separate commitment loss that pulls the encoder toward the code: \begin {equation} \mathcal {L}_{\mbox{commit}} = \beta \left \| \mathbf {z}_e(i,j) - \texttt{sg}[\mathbf {e}_{k^\star (i,j)}] \right \|_2^2. \label {eq:chapter20_vqvae_commitment_loss} \end {equation} Intuitively, \(\mathcal {L}_{\mbox{codebook}}\) updates the codes to match the data, while \(\mathcal {L}_{\mbox{commit}}\) updates the encoder to commit to the chosen codes.

(b) EMA-Based Codebook Update (Used in Practice) An alternative strategy, widely used in modern implementations, updates the codebook using an Exponential Moving Average (EMA). To understand this approach, it is helpful to view Vector Quantization as an online version of K-Means clustering.

Intuition: The Centroid Logic. In ideal clustering, the optimal position for a cluster center (codebook vector \(\mathbf {e}_k\)) is the average (centroid) of all data points (encoder outputs \(\mathbf {z}_e\)) assigned to it. \[ \mathbf {e}_k^{\mbox{optimal}} = \frac {\sum \mathbf {z}_e \mbox{ assigned to } k}{\mbox{Count of } \mathbf {z}_e \mbox{ assigned to } k} \] Unlike K-Means, which processes the entire dataset at once, deep learning processes data in small batches. Updating the codebook to match the mean of a single batch would be unstable (the codebook would jump around wildly based on the specific images in that batch).

The EMA Solution. Instead of jumping to the batch mean, we maintain a running average of the sum and the count over time. We define two running statistics for each code \(k\):

- \(N_k\): The running count (total ”mass”) of encoder vectors assigned to code \(k\).

- \(M_k\): The running sum (total ”momentum”) of encoder vectors assigned to code \(k\).

For a given batch, we first compute the statistics just for that batch: \[ n_k^{\mbox{batch}} = \sum _{i,j} \mathbf {1}[k^\star (i,j)=k], \qquad m_k^{\mbox{batch}} = \sum _{i,j} \mathbf {1}[k^\star (i,j)=k] \,\mathbf {z}_e(i,j). \] We then smoothly update the long-term statistics using a decay factor \(\gamma \) (typically \(0.99\)): \begin {equation} N_k^{(t)} \leftarrow \underbrace {\gamma N_k^{(t-1)}}_{\mbox{History}} + \underbrace {(1-\gamma )\, n_k^{\mbox{batch}}}_{\mbox{New Data}}, \qquad M_k^{(t)} \leftarrow \gamma M_k^{(t-1)} + (1-\gamma )\, m_k^{\mbox{batch}}. \label {eq:chapter20_vqvae_ema_stats} \end {equation}

Deriving the Update. Finally, to find the current codebook vector \(\mathbf {e}_k\), we simply calculate the centroid using our running totals: \begin {equation} \mathbf {e}_k^{(t)} = \frac {\mbox{Total Sum}}{\mbox{Total Count}} = \frac {M_k^{(t)}}{N_k^{(t)}}. \label {eq:chapter20_vqvae_ema_codebook} \end {equation}

Why update this way?

- Stability: This method avoids the need for a learning rate on the codebook. The codebook vectors evolve smoothly as weighted averages of the data they represent, reducing the oscillatory behavior often seen with standard gradient descent.

- Robustness: It mimics running K-Means on the entire dataset stream, ensuring codes eventually converge to the true centers of the latent distribution.

In this variant, the encoder is still trained via the straight-through estimator and commitment loss. The only difference is that the codebook vectors are updated analytically, effectively smoothing out the prototype dynamics.

- Gradient-based: Updates \(\mathbf {e}_{k^\star }\) via \(\mathcal {L}_{\mbox{codebook}}\) (Eq. 20.7). Requires balancing with commitment loss; moves codes via standard optimizer steps.

- EMA-based: Updates \(\mathbf {e}_k\) via running statistics (Eq. 20.10). Acts as a stable, online K-Means update, ignoring gradients for the codebook itself.

3. Commitment Loss (\( \mathcal {L}_{\mbox{commit}} \)) This term encourages encoder outputs to stay close to the quantized embeddings to which they are assigned: \[ \mathcal {L}_{\mbox{commit}} = \| \mathbf {z}_e - \texttt{sg}[\mathbf {e}] \|_2^2 \] Here, we stop the gradient on \( \mathbf {e} \), updating only the encoder. This penalizes encoder drift and forces it to ”commit” to one of the fixed embedding vectors in the codebook.

Why Two Losses with Stop-Gradients Are Needed We require both the codebook and commitment losses to properly manage the interaction between the encoder and the discrete latent space.

Intuition: The Dog and the Mat. Why can’t we just let both the encoder and codebook update freely toward each other? Imagine trying to teach a dog (the Encoder) to sit on a mat (the Codebook Vector).

- Without Stop Gradients (The Chase): If you move the mat toward the dog at the same time the dog moves toward the mat, they will meet in a random middle spot. Next time, the dog moves further, and the mat chases it again. The mat never stays in one place long enough to become a reliable reference point (“anchor”). The codebook vectors would wander endlessly (oscillate) and fail to form meaningful clusters.

-

With Stop Gradients (Alternating Updates):

- Codebook Loss: We freeze the Encoder. We move the Codebook vector to the center of the data points assigned to it (like moving the mat to where the dog prefers to sit). This makes the codebook a good representative of the data.

- Commitment Loss: We freeze the Codebook. We force the Encoder to produce outputs close to the current Codebook vector. This prevents the Encoder’s output from growing arbitrarily large or drifting away from the allowed ”dictionary” of codes.

The stop-gradient operator ensures that only one component — either the encoder or the codebook — is updated by each loss term. This separation is essential for training stability.

Compact Notation for Vector Quantization Loss The two terms above are often grouped together as the vector quantization loss: \[ \mathcal {L}_{\mbox{VQ}} = \| \texttt{sg}[\mathbf {z}_e] - \mathbf {e} \|_2^2 + \beta \| \mathbf {z}_e - \texttt{sg}[\mathbf {e}] \|_2^2 \]

- 1.

- Encode the image \( \mathbf {x} \) into latent maps: \[ \mathbf {x} \rightarrow \mathbf {z}_b^e \rightarrow \mathbf {z}_t^e \]

- 2.

- Quantize both latent maps: \[ \mathbf {z}_b^q(i,j) = \mathcal {C}^{(b)}[\mathbf {i}_b(i,j)], \quad \mathbf {z}_t^q(i,j) = \mathcal {C}^{(t)}[\mathbf {i}_t(i,j)] \] where \( \mathbf {i}_b, \mathbf {i}_t \in \{1, \dots , K\} \) are index maps pointing to codebook entries.

- 3.

- Decode the quantized representations: \[ \hat {\mathbf {x}} = D(\mathbf {z}_t^q, \mathbf {z}_b^q) \]

- 4.

- Compute the total loss: \[ \mathcal {L} = \| \mathbf {x} - \hat {\mathbf {x}} \|_2^2 + \sum _{\ell \in \{t,b\}} \left [ \| \texttt{sg}[\mathbf {z}_e^{(\ell )}] - \mathbf {e}^{(\ell )} \|_2^2 + \beta \| \mathbf {z}_e^{(\ell )} - \texttt{sg}[\mathbf {e}^{(\ell )}] \|_2^2 \right ] \]

- 5.

- Backpropagate gradients and update:

- Encoder and decoder weights.

- Codebook embeddings.

Training Summary with EMA Codebook Updates If using EMA for codebook updates, the total loss becomes:

\[ \mathcal {L}_{\mbox{VQ-VAE-2}} = \underbrace {\| \mathbf {x} - \hat {\mathbf {x}} \|_2^2}_{\mbox{Reconstruction}} + \underbrace {\beta \| \mathbf {z}_e - \texttt{sg}[\mathbf {e}] \|_2^2}_{\mbox{Commitment Loss}} \]

The codebook is updated separately using exponential moving averages, not through gradient-based optimization.

This concludes the training of the VQ-VAE-2 autoencoder. Once trained and converged, the encoder, decoder, and codebooks are frozen, and we proceed to the next stage: training the autoregressive PixelCNN priors over the discrete latent indices.

Training the Autoregressive Priors

Motivation Once the VQ-VAE-2 autoencoder has been trained to compress and reconstruct images via quantized latents, we aim to turn it into a fully generative model. However, we cannot directly sample from the latent codebooks unless we learn to generate plausible sequences of discrete latent indices — this is where PixelCNN priors come into play.

These priors model the distribution over the discrete index maps produced by the quantization process: \[ \mathbf {i}_t \in \{1, \dots , K\}^{H_t \times W_t}, \quad \mathbf {i}_b \in \{1, \dots , K\}^{H_b \times W_b} \]

Hierarchical Modeling: Why separate priors? Two PixelCNNs are trained after the autoencoder components (encoders, decoder, codebooks) have been frozen. We use two separate models because they solve fundamentally different probability tasks:

-

Top-Level Prior (\( \mbox{PixelCNN}_t \)):

This models the unconditional prior \( p(\mathbf {i}_t) \), i.e., the joint distribution over top-level latent indices. It generates the “big picture” structure from scratch and has no context to rely on. \[ p(\mathbf {i}_t) = \prod _{h=1}^{H_t} \prod _{w=1}^{W_t} p\left ( \mathbf {i}_t[h, w] \,\middle |\, \mathbf {i}_t[<h, :],\, \mathbf {i}_t[h, <w] \right ) \] Here, each index is sampled conditioned on previously generated indices in raster scan order — rows first, then columns.

-

Bottom-Level Prior (\( \mbox{PixelCNN}_b \)):

This models the conditional prior \( p(\mathbf {i}_b \mid \mathbf {i}_t) \). It fills in fine details (texture). Crucially, it is conditioned on the top-level map. It asks: “Given that the top level says this area is a Face, what specific skin texture pixels should I put here?” \[ p(\mathbf {i}_b \mid \mathbf {i}_t) = \prod _{h=1}^{H_b} \prod _{w=1}^{W_b} p\left ( \mathbf {i}_b[h, w] \,\middle |\, \mathbf {i}_b[<h, :],\, \mathbf {i}_b[h, <w],\, \mathbf {i}_t \right ) \] Each index \( \mathbf {i}_b[h,w] \) is conditioned on both previously generated indices in \( \mathbf {i}_b \) and the full top-level map \( \mathbf {i}_t \).

- The PixelCNNs are trained using standard cross-entropy loss on the categorical distributions over indices.

- Training examples are collected by passing training images through the frozen encoder and recording the resulting index maps \( \mathbf {i}_t \), \( \mathbf {i}_b \).

-

The models are trained separately:

- PixelCNN\(_t\): trained on samples of \( \mathbf {i}_t \)

- PixelCNN\(_b\): trained on \( \mathbf {i}_b \) conditioned on \( \mathbf {i}_t \)

Sampling Procedure At inference time (for unconditional generation), we proceed as follows:

- 1.

- Sample \( \hat {\mathbf {i}}_t \sim p(\mathbf {i}_t) \) using PixelCNN\(_t\).

- 2.

- Sample \( \hat {\mathbf {i}}_b \sim p(\mathbf {i}_b \mid \hat {\mathbf {i}}_t) \) using PixelCNN\(_b\).

- 3.

- Retrieve quantized codebook vectors: \[ \mathbf {z}_t^q[h, w] = \mathcal {C}^{(t)}[\hat {\mathbf {i}}_t[h, w]], \quad \mathbf {z}_b^q[h, w] = \mathcal {C}^{(b)}[\hat {\mathbf {i}}_b[h, w]] \]

- 4.

- Decode \( (\mathbf {z}_t^q, \mathbf {z}_b^q) \rightarrow \hat {\mathbf {x}} \)

Initialization Note Since PixelCNNs are autoregressive models, they generate each element of the output one at a time, conditioned on the previously generated elements in a predefined order (usually raster scan — left to right, top to bottom). However, at the very beginning of sampling, no context exists yet for the first position.

To address this, we initialize the grid of latent indices with an empty or neutral state — typically done by either:

- Padding the grid with a fixed value (e.g., all zeros) to serve as an artificial context for the first few pixels.

- Treating the first position \( (0,0) \) as unconditional and sampling it directly from the learned marginal distribution.

From there, sampling proceeds autoregressively:

- For each spatial position \( (h, w) \), the PixelCNN uses all previously sampled values (e.g., those above and to the left of the current location) to predict a probability distribution over possible code indices.

- A discrete index is sampled from this distribution, placed at position \( (h, w) \), and used as context for the next position.

This procedure is repeated until the full latent index map is generated.

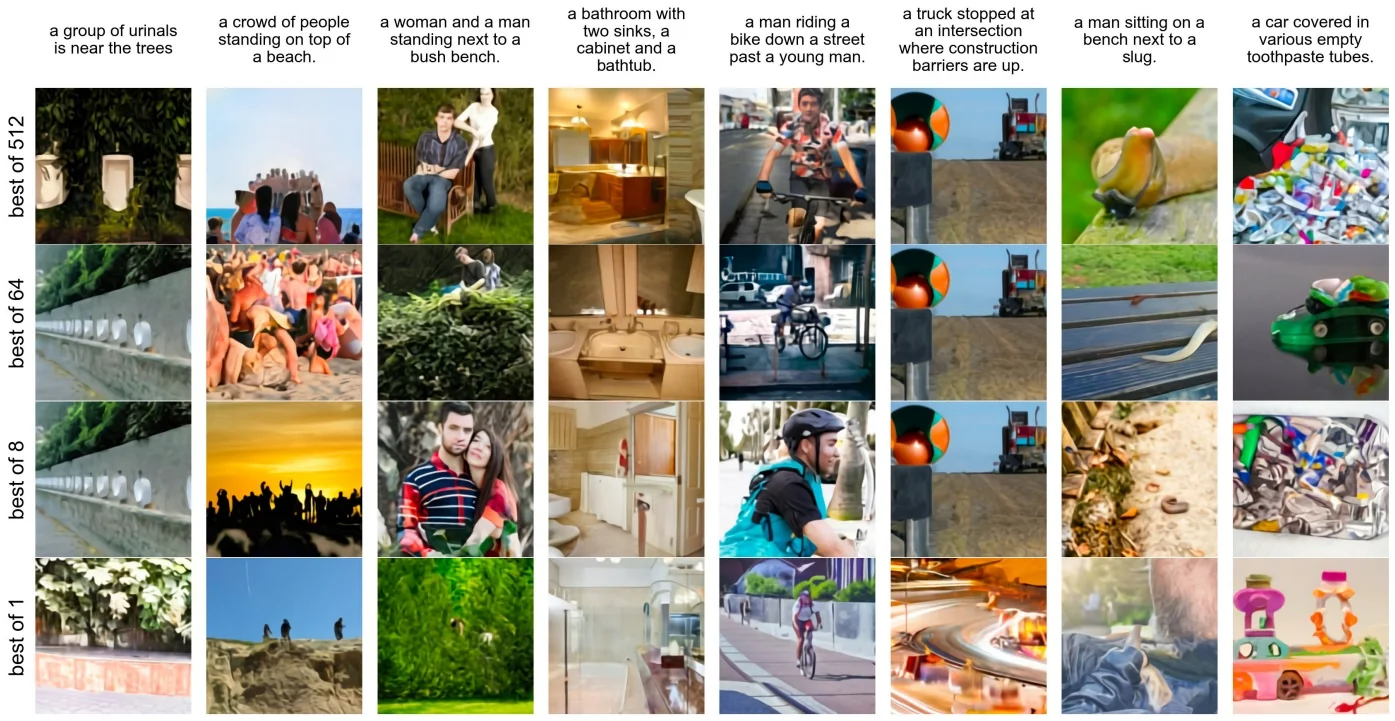

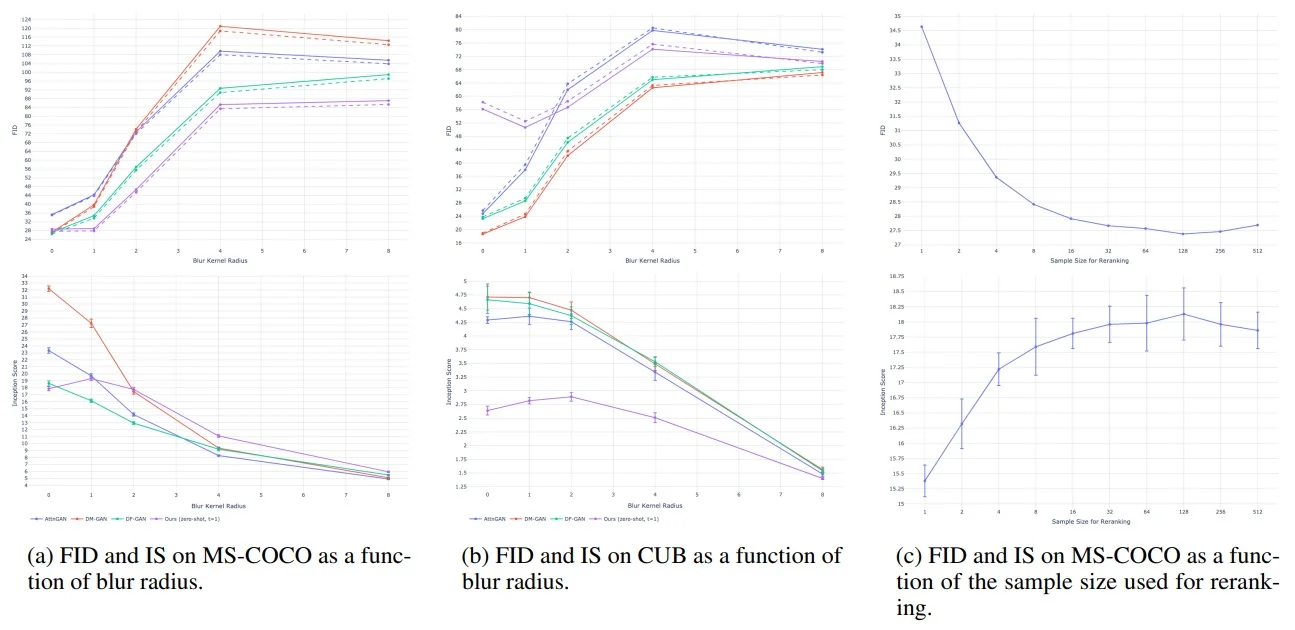

Advantages and Limitations of VQ-VAE-2 VQ-VAE-2 couples a discrete latent autoencoder with autoregressive priors (PixelCNN-style) over latent indices. This hybrid design inherits strengths from both latent-variable modeling and autoregressive likelihood modeling, but it also exposes specific trade-offs.

-

Advantages

- High-quality generation via abstract autoregression. Instead of predicting pixels one-by-one, the prior models the joint distribution of discrete latent indices at a much lower spatial resolution. This pushes autoregression to a more abstract level, capturing long-range global structure (layout, pose) while the decoder handles local detail.

- Efficient sampling relative to pixel-space. By operating on a compressed (and hierarchical) grid of latent indices, the effective sequence length is drastically reduced compared to full-resolution pixel autoregression, making high-resolution synthesis more practical.

- Modularity and reuse. The learned discrete autoencoder provides a standalone, reusable image decoder. One can retrain the computationally cheaper PixelCNN prior for new tasks (e.g., class-conditional generation) while keeping the expensive autoencoder fixed.

- Compact, semantically structured representation. Vector quantization yields a discrete code sequence that acts as a learned compression of the image, naturally suiting tasks like compression, retrieval, and semantic editing.

-

Limitations

- Sequential priors remain a bottleneck. Despite the compressed grid, the priors generate indices sequentially (raster-scan order). This inherent sequentiality limits inference speed compared to fully parallel (one-shot) generators.

- Training complexity. The multi-stage pipeline—(i) training the discrete autoencoder, then (ii) training hierarchical priors—is often more cumbersome to tune and engineer compared to end-to-end approaches.

- Reconstruction bias (Blur). The autoencoder is typically trained with pixel-space losses (like \(L_2\)), which mathematically favor ”average” predictions. This can result in a loss of high-frequency texture details, as the model avoids committing to sharp, specific modes in the output distribution.

The Pivot to Adversarial Learning. While VQ-VAE-2 achieved state-of-the-art likelihood results, the limitations highlighted above—specifically the sequential sampling speed and the blur induced by reconstruction losses—set the stage for our next topic.

To achieve real-time, one-shot generation and to optimize strictly for perceptual realism (ignoring pixel-wise averages), we must abandon explicit density estimation. We now turn to Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), which solve these problems by training a generator not to match a probability distribution, but to defeat a competitor.

20.4 Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs)

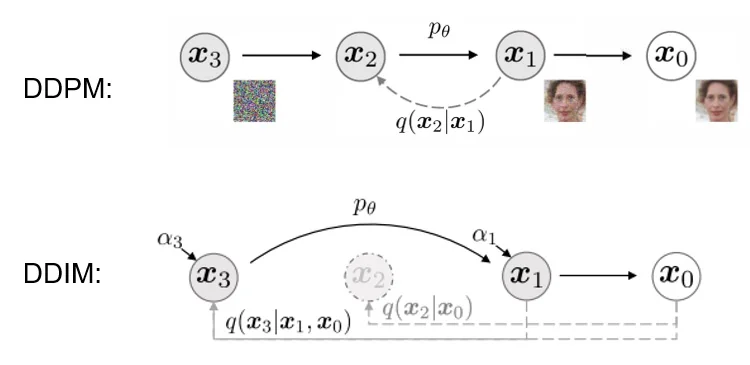

Bridging from Autoregressive Models, VAEs to GANs Up to this point, we have studied explicit generative models:

- Autoregressive models (e.g., PixelCNN) directly model the data likelihood \( p(\mathbf {x}) \) by factorizing it into a sequence of conditional distributions. These models produce high-quality samples but suffer from slow sampling, since each pixel (or token) is generated sequentially.

- Variational Autoencoders (VAEs) introduce latent variables \( \mathbf {z} \) and define a variational lower bound on \( \log p(\mathbf {x}) \), which they optimize during training. While VAEs allow fast sampling, their outputs are often blurry due to overly simplistic priors and decoders.

- VQ-VAE-2 combines the strengths of both worlds. It learns a discrete latent space via vector quantization, and models its distribution using autoregressive priors like PixelCNN — allowing for efficient compression and high-quality generation. Crucially, although it uses autoregressive models, sampling happens in a much lower-resolution latent space, making generation significantly faster than pixel-level autoregression.

Despite these advancements, all of the above methods explicitly define or approximate a probability density \( p(\mathbf {x}) \), or a lower bound thereof. This requires likelihood-based objectives and careful modeling of distributions, which can introduce challenges such as:

- Trade-offs between sample fidelity and likelihood maximization (e.g., in VAEs).

- Architectural constraints imposed by factorized likelihood models (e.g., PixelCNN).

This leads us to a fundamentally different approach: Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs). GANs completely sidestep the need to model \( p(\mathbf {x}) \) explicitly — instead, they define a sampling process that generates data, and train it using a learned adversary that distinguishes real from fake. In the next section, we introduce this adversarial framework in detail.

Enter GANs Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) [180] are based on a radically different principle. Rather than trying to compute or approximate the density function \( p(\mathbf {x}) \), GANs focus on generating samples that are indistinguishable from real data.

They introduce a new type of generative model called an implicit model: we never write down \( p(\mathbf {x}) \), but instead learn a mechanism for sampling from it.

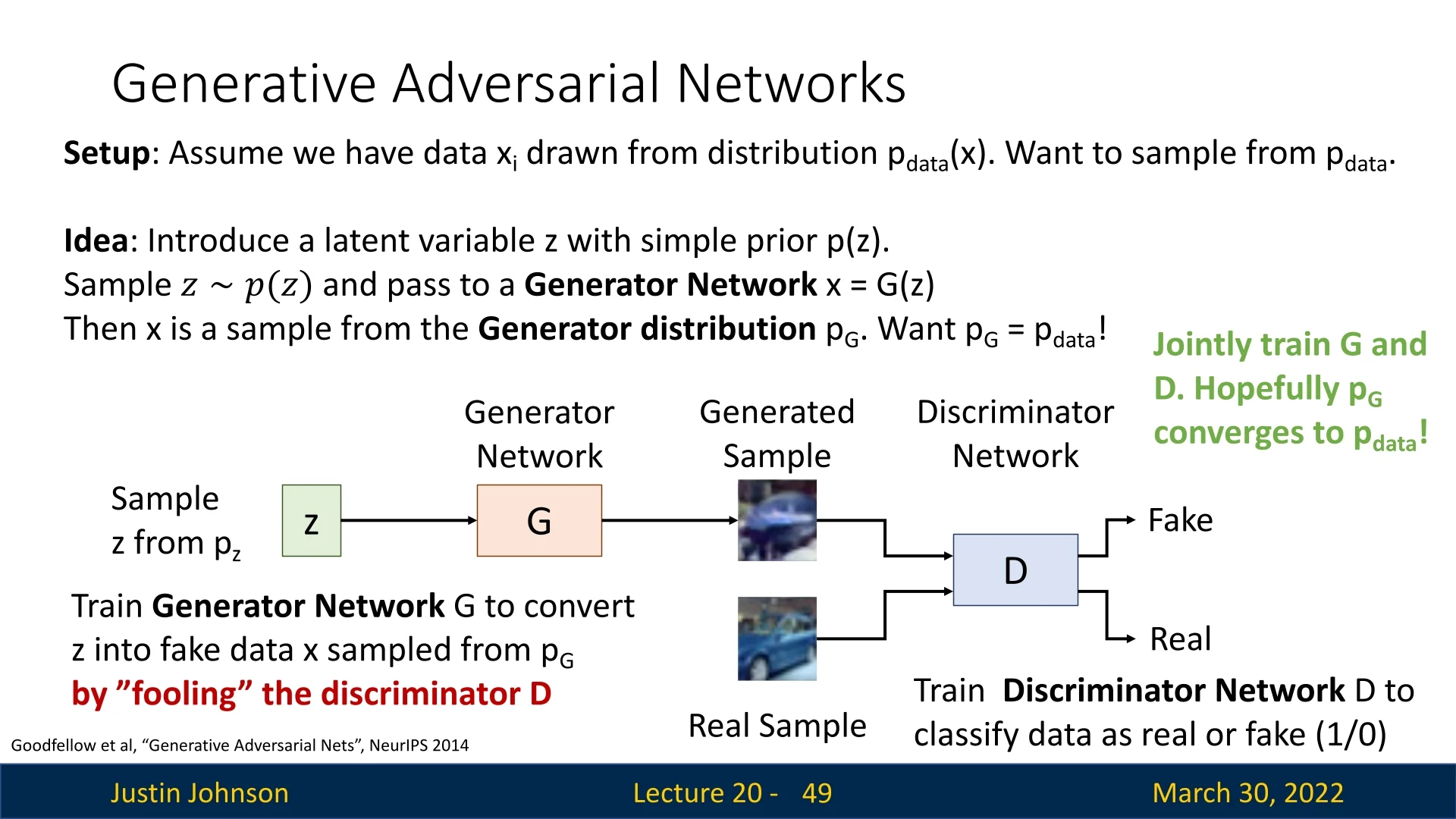

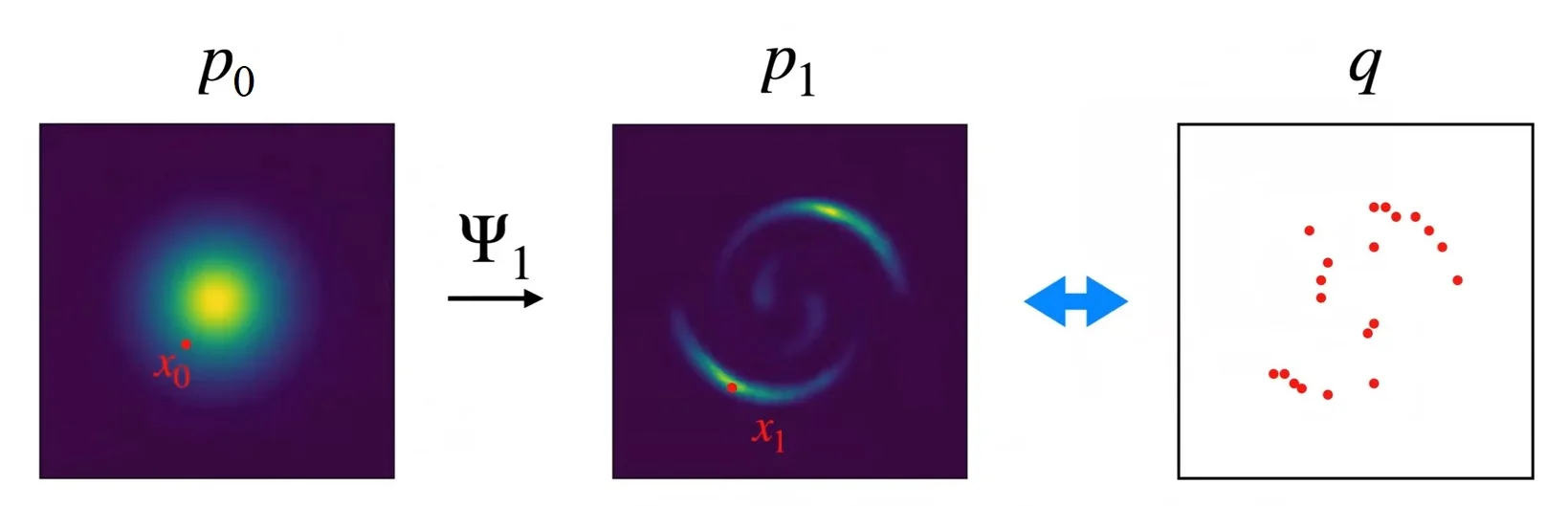

20.4.1 Setup: Implicit Generation via Adversarial Learning

Sampling from the True Distribution Let \( \mathbf {x} \sim p_{\mbox{data}}(\mathbf {x}) \) be a sample from the real data distribution — for instance, natural images. This distribution is unknown and intractable to express, but we assume we have access to i.i.d. samples from it (e.g., a dataset of images).

Our goal is to train a model whose samples are indistinguishable from those of \( p_{\mbox{data}} \). To this end, we adopt a latent variable model:

- Define a simple latent distribution \( p(\mathbf {z}) \), such as a standard Gaussian \( \mathcal {N}(0, \mathbf {I}) \) or uniform distribution.

- Sample a latent code \( \mathbf {z} \sim p(\mathbf {z}) \).

- Pass it through a neural network generator \( \mathbf {x} = G(\mathbf {z}) \) to produce a data sample.

This defines a generator distribution \( p_G(\mathbf {x}) \), where the sampling path is: \[ \mathbf {z} \sim p(\mathbf {z}) \quad \Rightarrow \quad \mathbf {x} = G(\mathbf {z}) \sim p_G(\mathbf {x}) \]

The key challenge is that we cannot write down \( p_G(\mathbf {x}) \) explicitly — it is an implicit distribution defined by the transformation of noise through a neural network.

Discriminator as a Learned Judge To bring \( p_G \) closer to \( p_{\mbox{data}} \), GANs introduce a second neural network: the discriminator \( D(\mathbf {x}) \), which is trained as a binary classifier. It receives samples from either the real distribution \( p_{\mbox{data}} \) or the generator \( p_G \), and must learn to classify them as: \[ D(\mathbf {x}) = \begin {cases} 1 & \mbox{if } \mathbf {x} \sim p_{\mbox{data}} \ (\mbox{real}) \\ 0 & \mbox{if } \mathbf {x} \sim p_G \ (\mbox{fake}) \end {cases} \]

The generator \( G \), meanwhile, is trained to fool the discriminator — it learns to produce samples that the discriminator cannot distinguish from real data.

Adversarial Training Dynamics The result is a two-player game: the generator tries to minimize the discriminator’s ability to detect fakes, while the discriminator tries to maximize its classification accuracy.

- The discriminator \( D \) is trained to maximize the probability of correctly identifying real vs. generated data.

- The generator \( G \) is trained to minimize this probability — i.e., to make generated data look real.

At equilibrium, the discriminator is maximally uncertain (i.e., it assigns probability 0.5 to all inputs), and the generator’s distribution \( p_G \) matches the real distribution \( p_{\mbox{data}} \).

Core Intuition The fundamental idea of GANs is to reframe generative modeling as a discrimination problem: if we can’t explicitly define what makes a good image, we can still train a network to tell real from fake — and then invert this process to generate better samples.

In the next part, we will formalize this game-theoretic setup and introduce the original GAN loss proposed by Goodfellow et al. [180], including its connection to Jensen–Shannon divergence, optimization challenges, and variants.

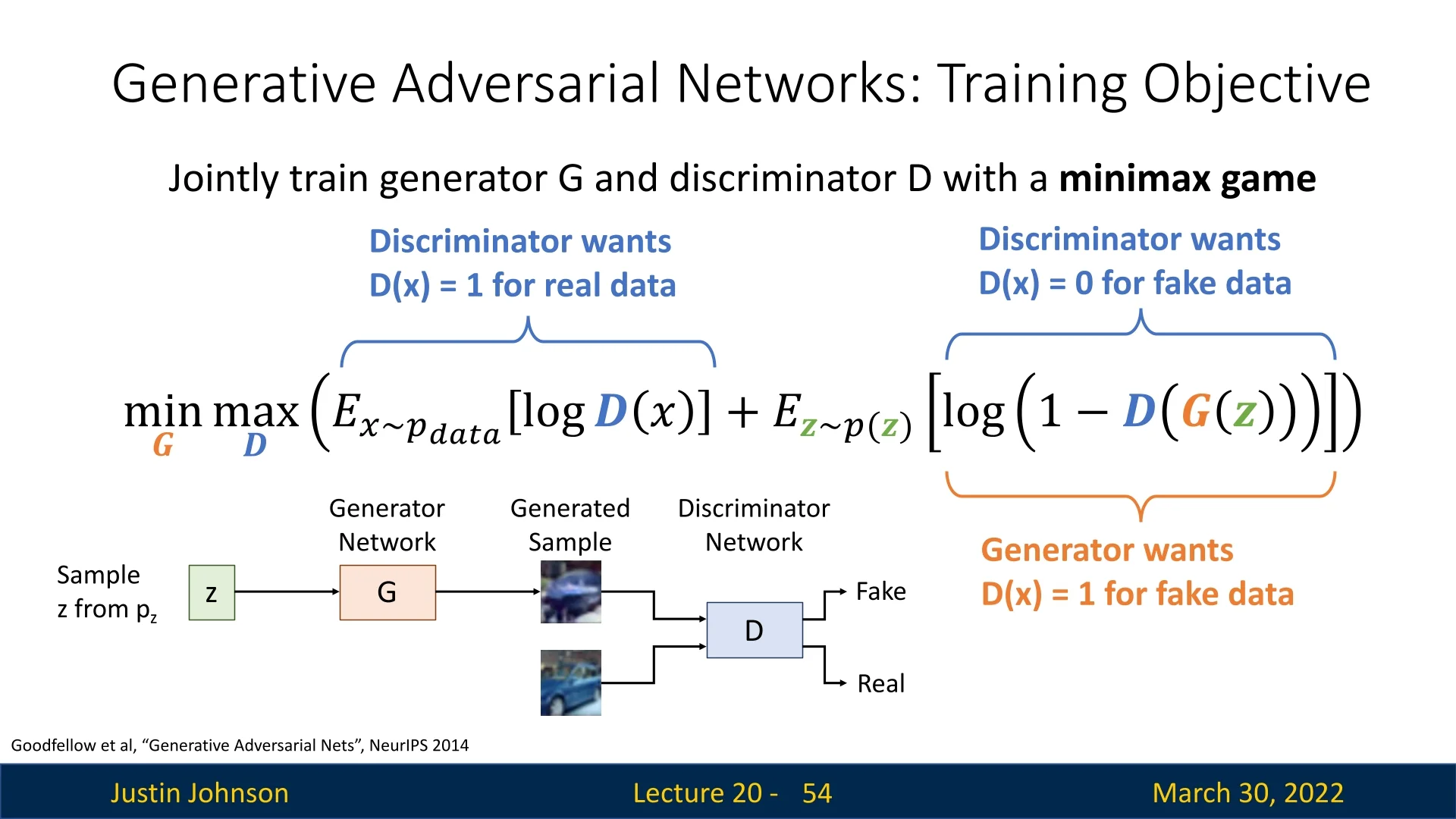

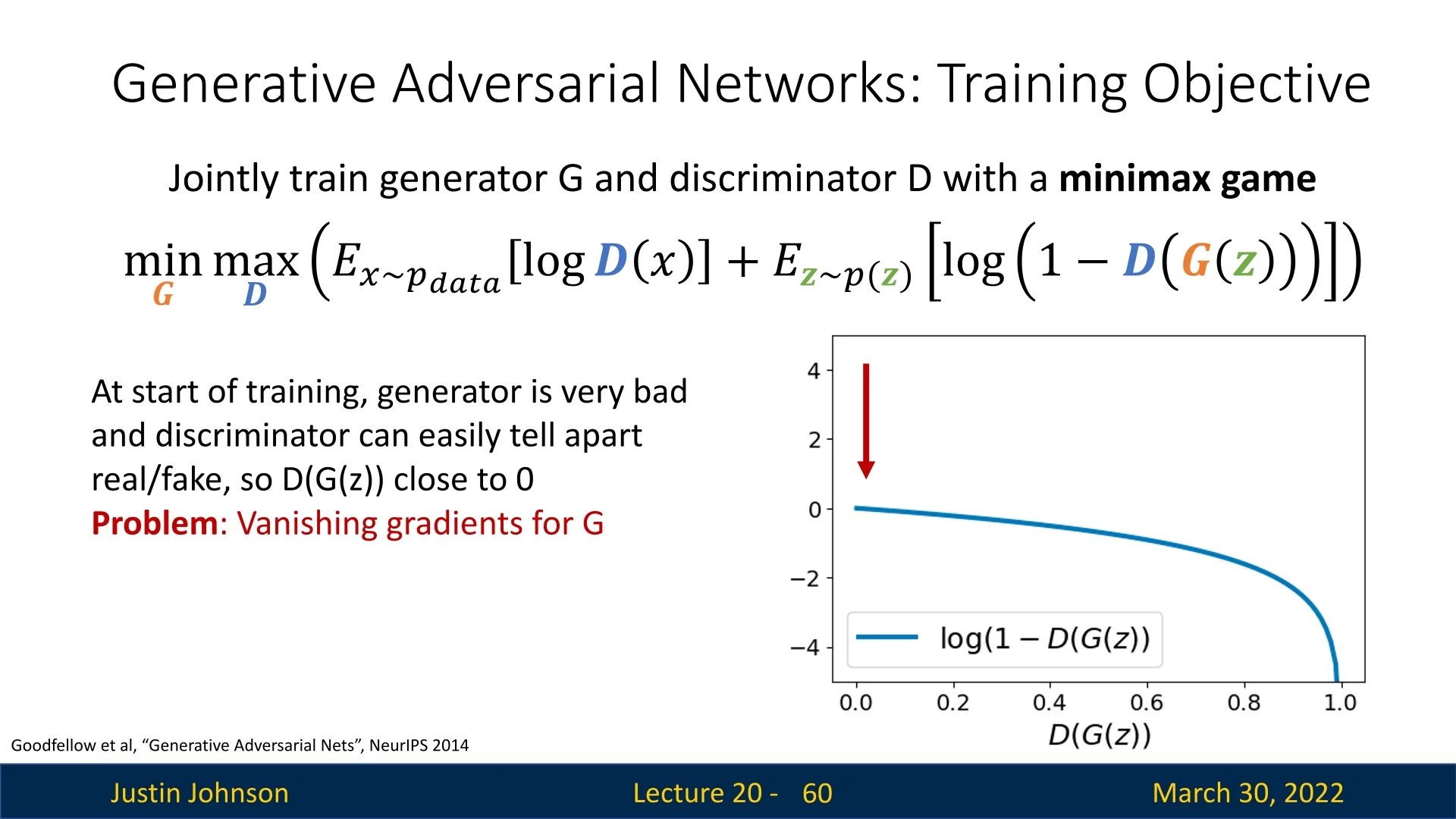

20.4.2 GAN Training Objective

We define a two-player minimax game between \( G \) and \( D \). The discriminator aims to classify real vs. fake images, while the generator tries to fool the discriminator. The objective function is: \[ \min _G \max _D \; V(D, G) = \mathbb {E}_{\mathbf {x} \sim p_{\mbox{data}}} \left [ \log D(\mathbf {x}) \right ] + \mathbb {E}_{\mathbf {z} \sim p(\mathbf {z})} \left [ \log (1 - D(G(\mathbf {z}))) \right ] \]

-

The discriminator maximizes both terms:

- \( \log D(\mathbf {x}) \) encourages \( D \) to classify real data as real (i.e., \( D(\mathbf {x}) \rightarrow 1 \)).

- \( \log (1 - D(G(\mathbf {z}))) \) encourages \( D \) to classify generated samples as fake (i.e., \( D(G(\mathbf {z})) \rightarrow 0 \)).

- The generator minimizes the second term: \[ \mathbb {E}_{\mathbf {z} \sim p(\mathbf {z})} \left [ \log (1 - D(G(\mathbf {z}))) \right ] \] This term is minimized when \( D(G(\mathbf {z})) \rightarrow 1 \), i.e., when the discriminator believes generated samples are real.

The generator and discriminator are trained jointly using alternating gradient updates: \[ \mbox{for } t = 1, \dots , T: \begin {cases} D \leftarrow D + \alpha _D \nabla _D V(G, D) \\ G \leftarrow G - \alpha _G \nabla _G V(G, D) \end {cases} \]

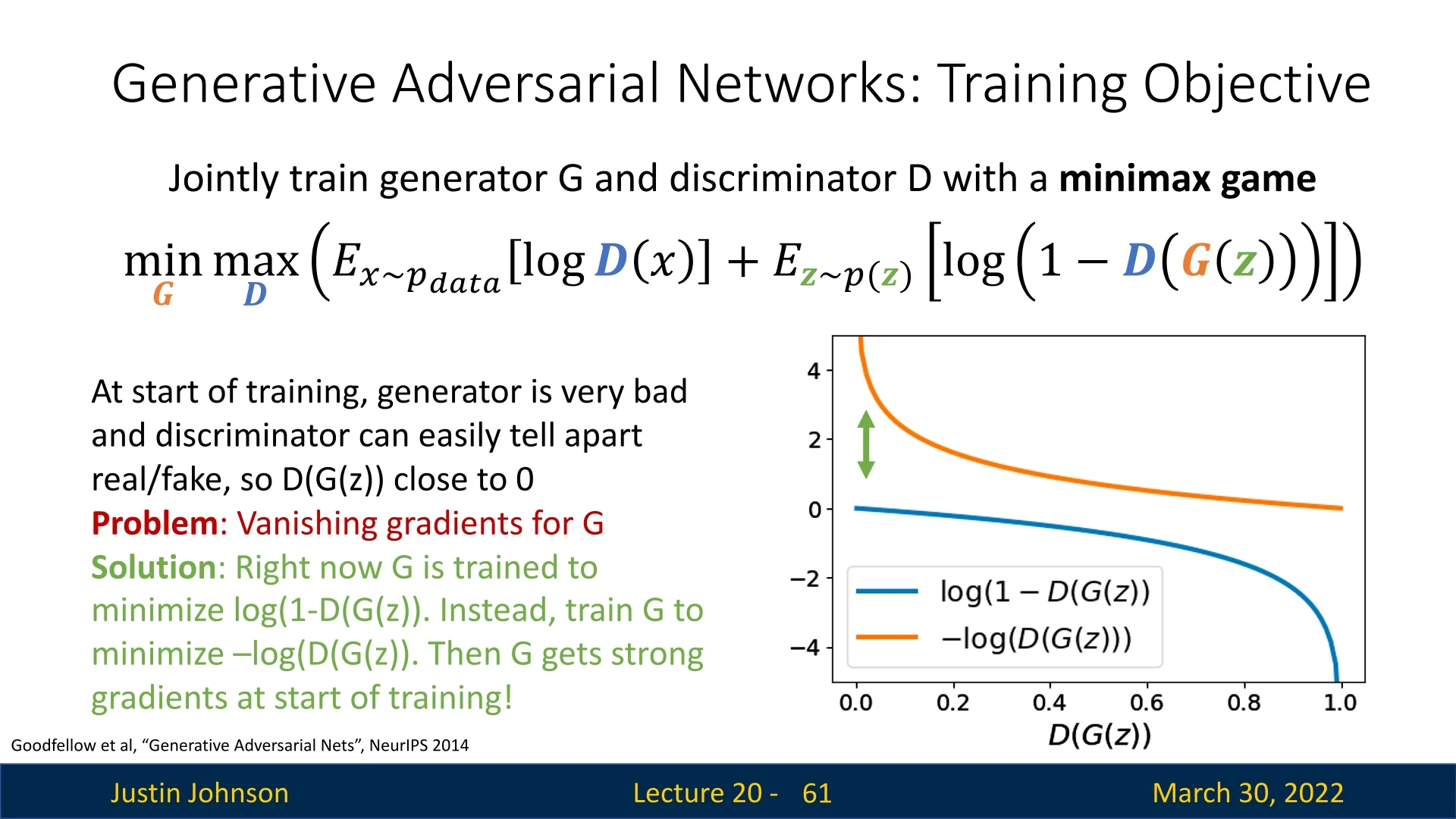

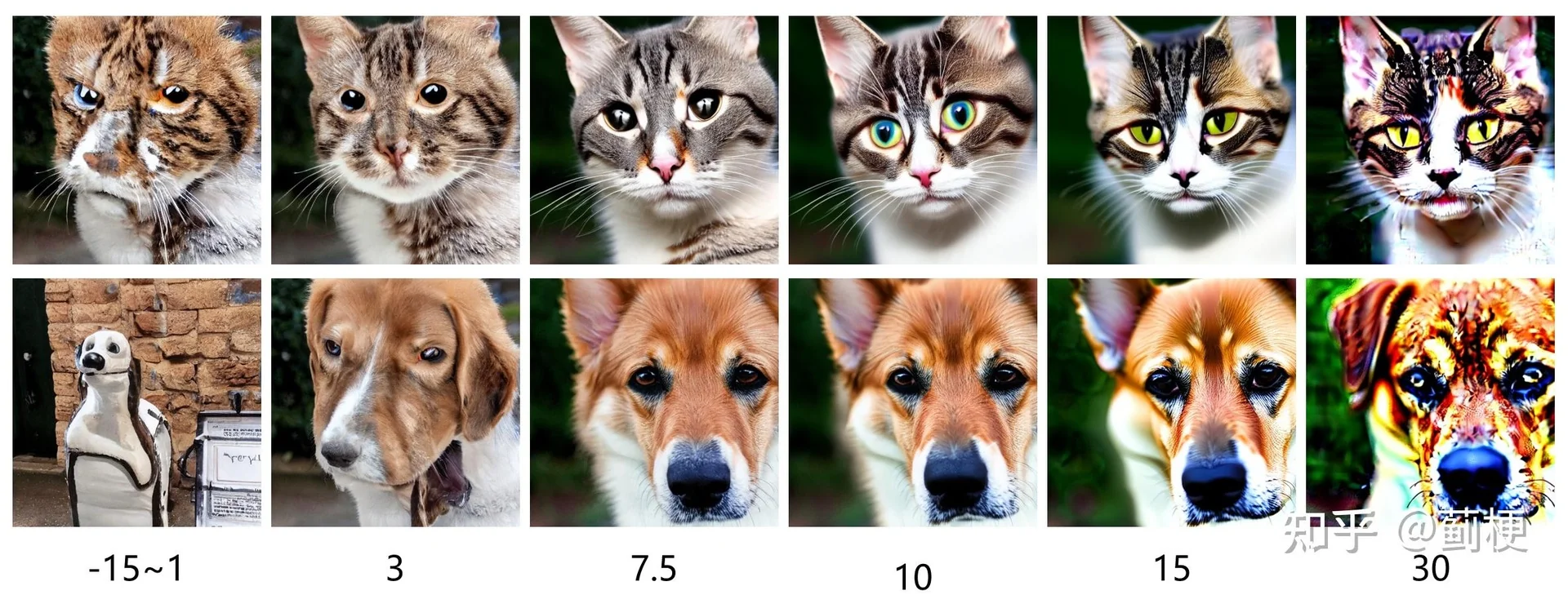

Difficulties in Optimization GAN training is notoriously unstable due to the adversarial dynamics. Two critical issues arise:

- No single loss is minimized: GAN training is a minimax game. The generator and discriminator influence each other’s gradients, making it difficult to assess convergence or use standard training curves.

-

Vanishing gradients early in training: When \( G \) is untrained, it produces unrealistic images. This makes it easy for \( D \) to assign \( D(G(\mathbf {z})) \approx 0 \), saturating the term \( \log (1 - D(G(\mathbf {z}))) \). Since \( \log (1 - x) \) flattens near \( x = 0 \), this leads to vanishing gradients for the generator early on.

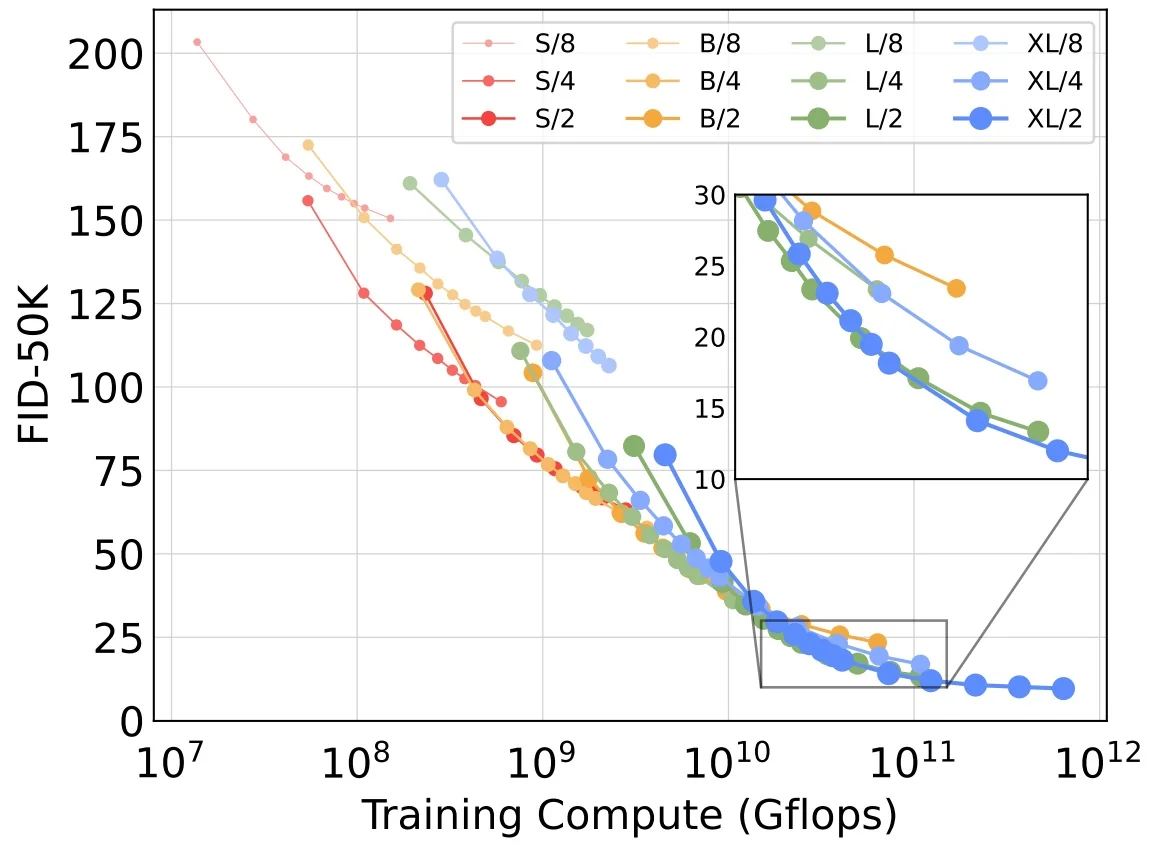

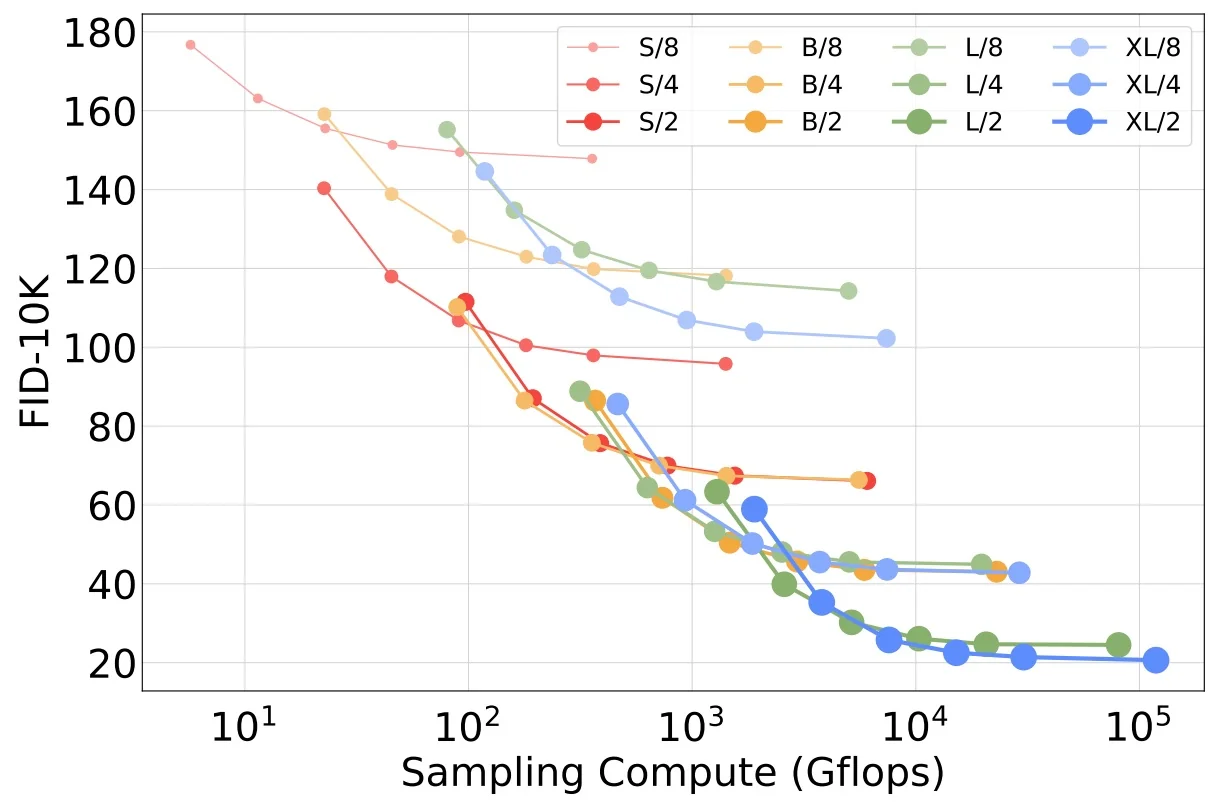

Figure 20.15: At the start of training, the generator produces poor samples. The discriminator easily identifies them, yielding vanishing gradients for the generator.

Modified Generator Loss (Non-Saturating Trick) In the original minimax objective proposed in [180], the generator is trained to minimize: \[ \mathbb {E}_{\mathbf {z} \sim p(\mathbf {z})} \left [ \log (1 - D(G(\mathbf {z}))) \right ] \] This objective encourages \( G \) to generate images that the discriminator believes are real. However, it suffers from a critical problem early in training: when the generator is poor and produces unrealistic images, the discriminator assigns very low scores \( D(G(\mathbf {z})) \approx 0 \). As a result, \( \log (1 - D(G(\mathbf {z}))) \approx 0 \), and its gradient vanishes: \[ \frac {\mathrm {d}}{\mathrm {d}G} \log (1 - D(G(\mathbf {z}))) \rightarrow 0 \]

This leads to extremely weak updates to the generator — just when it needs them most.

Solution: Switch the Objective Instead of minimizing \( \log (1 - D(G(\mathbf {z}))) \), we train the generator to maximize: \[ \mathbb {E}_{\mathbf {z} \sim p(\mathbf {z})} \left [ \log D(G(\mathbf {z})) \right ] \]

This change does not alter the goal — the generator still wants the discriminator to classify its outputs as real — but it yields stronger gradients, especially when \( D(G(\mathbf {z})) \) is small (i.e., when the discriminator is confident the generated image is fake).

Why does this work?

- For small inputs, \( \log (1 - x) \) is nearly flat (leading to vanishing gradients), while \( \log (x) \) is sharply sloped.

- So when \( D(G(\mathbf {z})) \) is close to zero, minimizing \( \log (1 - D(G(\mathbf {z}))) \) gives negligible gradients, while maximizing \( \log (D(G(\mathbf {z}))) \) gives large, informative gradients.

This variant is known as the non-saturating generator loss, and is widely used in practice for training stability.

Looking Ahead: Why This Objective? We have introduced the practical GAN training objective. But why this specific formulation? Is it theoretically sound? What happens when \( D \) is optimal? Does the generator recover the true data distribution \( p_{\mbox{data}} \)? In the next section, we analyze these questions and uncover the theoretical justification for adversarial training.

20.4.3 Why the GAN Training Objective Is Optimal

Step-by-Step Derivation We begin with the original minimax GAN objective from [180]. Our goal is to analyze the equilibrium of this game by characterizing the global minimum of the value function.

\begin {align*} \min _{\textcolor {darkorange}{G}} \max _{\textcolor {lightblue}{D}} \; & \mathbb {E}_{x \sim p_{\text {data}}}[\log \textcolor {lightblue}{D}(x)] + \mathbb {E}_{\textcolor {lightgreen}{z} \sim p(\textcolor {lightgreen}{z})}[\log (1 - \textcolor {lightblue}{D}(\textcolor {darkorange}{G}(\textcolor {lightgreen}{z})))] \quad \text {(Initial GAN objective)} \\ = \min _{\textcolor {darkorange}{G}} \max _{\textcolor {lightblue}{D}} \; & \mathbb {E}_{x \sim p_{\text {data}}}[\log \textcolor {lightblue}{D}(x)] + \mathbb {E}_{x \sim p_{\textcolor {darkorange}{G}}}[\log (1 - \textcolor {lightblue}{D}(x))] \quad \text {(Change of variables / LOTUS)} \\ = \min _{\textcolor {darkorange}{G}} \max _{\textcolor {lightblue}{D}} \; & \int _{\mathcal {X}} \left ( p_{\text {data}}(x) \log \textcolor {lightblue}{D}(x) + p_{\textcolor {darkorange}{G}}(x) \log (1 - \textcolor {lightblue}{D}(x)) \right ) dx \quad \text {(Definition of expectation)} \\ = \min _{\textcolor {darkorange}{G}} \; & \int _{\mathcal {X}} \max _{\textcolor {lightblue}{D(x)}} \left ( p_{\text {data}}(x) \log \textcolor {lightblue}{D}(x) + p_{\textcolor {darkorange}{G}}(x) \log (1 - \textcolor {lightblue}{D}(x)) \right ) dx \quad \text {(Push $\max _{\textcolor {lightblue}{D}}$ inside integral)} \end {align*}

Justification of the Mathematical Transformations To rigorously justify the steps above, we appeal to measure theory and the calculus of variations.

-

Change of Variables (The Pushforward and LOTUS):

The second term in the original objective is expressed as an expectation over latent variables \( \textcolor {lightgreen}{z} \sim p(\textcolor {lightgreen}{z}) \), with samples transformed through the generator: \( x = \textcolor {darkorange}{G}(\textcolor {lightgreen}{z}) \). This defines a new distribution over images, denoted \( \textcolor {darkorange}{p_G}(x) \), formally known as the pushforward measure (or generator distribution).The transition from an expectation over \( \textcolor {lightgreen}{z} \) to one over \( x \) is a direct application of the Law of the Unconscious Statistician (LOTUS). It guarantees that: \[ \mathbb {E}_{\textcolor {lightgreen}{z} \sim p(\textcolor {lightgreen}{z})} \left [ \log \left (1 - \textcolor {lightblue}{D}(\textcolor {darkorange}{G}(\textcolor {lightgreen}{z})) \right ) \right ] \quad \Rightarrow \quad \mathbb {E}_{x \sim \textcolor {darkorange}{p_G}(x)} \left [ \log \left (1 - \textcolor {lightblue}{D}(x) \right ) \right ] \] This reparameterization is valid because the pushforward distribution \( p_G \) exists. For the integral notation used subsequently, we further assume \( p_G \) admits a density with respect to the Lebesgue measure.

- Expectation to Integral:

Any expectation over a continuous random variable can be written as an integral: \[ \mathbb {E}_{x \sim p(x)}[f(x)] = \int _{\mathcal {X}} p(x) f(x) \, dx \] This applies to both the real data term and the generator term, allowing us to combine them into a single integral over the domain \( \mathcal {X} \). -

Pushing \( \max _D \) into the Integral (Functional Separability):

The discriminator \( \textcolor {lightblue}{D} \) is treated here as an arbitrary function defined pointwise over the domain \( \mathcal {X} \). This is an assumption of non-parametric optimization (i.e., we assume \( D \) has infinite capacity and is not constrained by a neural network architecture).Crucially, there is no dependence or coupling between \( \textcolor {lightblue}{D}(x_1) \) and \( \textcolor {lightblue}{D}(x_2) \) for different values of \( x \). Therefore, the objective functional is separable, and maximizing the global integral is equivalent to maximizing the integrand independently for each \( x \). \[ \max _{\textcolor {lightblue}{D}} \int _{\mathcal {X}} \cdots \; dx \quad \Longrightarrow \quad \int _{\mathcal {X}} \max _{\textcolor {lightblue}{D}(x)} \cdots \; dx \]

Solving the Inner Maximization (Discriminator) We now optimize the integrand pointwise for each \( x \in \mathcal {X} \), treating the discriminator output \( \textcolor {purple}{y} = \textcolor {purple}{D(x)} \) as a scalar variable. Define the objective at each point as: \[ f(\textcolor {purple}{y}) = \textcolor {darkred}{a} \log \textcolor {purple}{y} + \textcolor {darkeryellow}{b} \log (1 - \textcolor {purple}{y}), \quad \mbox{with} \quad \textcolor {darkred}{a} = p_{\mbox{data}}(x), \; \textcolor {darkeryellow}{b} = p_G(x) \] This function is strictly concave on \( \textcolor {purple}{y} \in (0, 1) \), and we compute the maximum by solving \( f'(\textcolor {purple}{y}) = 0 \): \[ f'(\textcolor {purple}{y}) = \frac {\textcolor {darkred}{a}}{\textcolor {purple}{y}} - \frac {\textcolor {darkeryellow}{b}}{1 - \textcolor {purple}{y}} = 0 \quad \Rightarrow \quad \textcolor {purple}{y} = \frac {\textcolor {darkred}{a}}{\textcolor {darkred}{a} + \textcolor {darkeryellow}{b}} \] Substituting back, the optimal value for the discriminator is: \[ \textcolor {lightblue}{D}^{*}_{\textcolor {darkorange}{G}}(x) = \frac {\textcolor {darkred}{p_{\mbox{data}}(x)}}{\textcolor {darkred}{p_{\mbox{data}}(x)} + \textcolor {darkeryellow}{p_G(x)}} \]

Here’s how the components map:

- \( p_{\mbox{data}}(x) \) (red) is the true data distribution at \( x \).

- \( D(x) \) (purple) is the scalar output of the discriminator.

- \( p_G(x) \) (dark yellow) is the generator’s distribution at \( x \).

This solution gives us the discriminator’s best possible output for any fixed generator \( G \). In the next step, we will plug this optimal discriminator back into the GAN objective to simplify the expression and reveal its connection to divergence measures.

Plugging the Optimal Discriminator into the Objective Having found the optimal discriminator \( \textcolor {lightblue}{D}^*_{\textcolor {darkorange}{G}} \) for a fixed generator, we now substitute it back into the game to evaluate the generator’s performance.

Recall that our goal is to minimize the value function \( V(\textcolor {darkorange}{G}, \textcolor {lightblue}{D}) \). Since the inner maximization is now solved, we focus on the Generator Value Function \( C(\textcolor {darkorange}{G}) \), which represents the generator’s loss when facing a perfect adversary: \[ C(\textcolor {darkorange}{G}) = \max _{\textcolor {lightblue}{D}} V(\textcolor {darkorange}{G}, \textcolor {lightblue}{D}) = V(\textcolor {darkorange}{G}, \textcolor {lightblue}{D}^*_{\textcolor {darkorange}{G}}) \]

To perform the substitution, let us first simplify the terms involving the optimal discriminator. Given \( \textcolor {lightblue}{D}^*_{\textcolor {darkorange}{G}}(x) = \frac {\textcolor {darkred}{p_{\mbox{data}}(x)}}{\textcolor {darkred}{p_{\mbox{data}}(x)} + \textcolor {darkeryellow}{p_G(x)}} \), the complementary probability (probability that the discriminator thinks a fake sample is fake) is: \[ 1 - \textcolor {lightblue}{D}^*_{\textcolor {darkorange}{G}}(x) = 1 - \frac {\textcolor {darkred}{p_{\mbox{data}}(x)}}{\textcolor {darkred}{p_{\mbox{data}}(x)} + \textcolor {darkeryellow}{p_G(x)}} = \frac {\textcolor {darkeryellow}{p_G(x)}}{\textcolor {darkred}{p_{\mbox{data}}(x)} + \textcolor {darkeryellow}{p_G(x)}} \]

We now replace \( \textcolor {lightblue}{D}(x) \) and \( (1-\textcolor {lightblue}{D}(x)) \) in the original integral objective with these expressions: \begin {align*} \min _{\textcolor {darkorange}{G}} C(\textcolor {darkorange}{G}) & = \min _{\textcolor {darkorange}{G}} \int _{\mathcal {X}} \Bigg ( \underbrace {\textcolor {darkred}{p_{\text {data}}(x)} \log \left ( \frac {\textcolor {darkred}{p_{\text {data}}(x)}} {\textcolor {darkred}{p_{\text {data}}(x)} + \textcolor {darkeryellow}{p_G(x)}} \right )}_{\text {Expected log-prob of real data}} + \underbrace {\textcolor {darkeryellow}{p_G(x)} \log \left ( \frac {\textcolor {darkeryellow}{p_G(x)}} {\textcolor {darkred}{p_{\text {data}}(x)} + \textcolor {darkeryellow}{p_G(x)}} \right )}_{\text {Expected log-prob of generated data}} \Bigg ) dx \end {align*}

Rewriting as KL Divergences The expression above resembles Kullback–Leibler (KL) divergence, but the denominators are sums, not distributions. To fix this, we need to compare \( \textcolor {darkred}{p_{\mbox{data}}} \) and \( \textcolor {darkeryellow}{p_G} \) against their average distribution (or mixture): \[ m(x) = \frac {\textcolor {darkred}{p_{\mbox{data}}(x)} + \textcolor {darkeryellow}{p_G(x)}}{2} \] We manipulate the log arguments by multiplying numerator and denominator by \( 2 \). This ”trick” is mathematically neutral (multiplying by \( 1 \)) but structurally revealing:

\begin {align*} = \min _{\textcolor {darkorange}{G}} \Bigg ( & \int _{\mathcal {X}} \textcolor {darkred}{p_{\text {data}}(x)} \log \left ( \frac {1}{2} \cdot \frac {\textcolor {darkred}{p_{\text {data}}(x)}}{\frac {\textcolor {darkred}{p_{\text {data}}(x)} + \textcolor {darkeryellow}{p_G(x)}}{2}} \right ) dx \\ + & \int _{\mathcal {X}} \textcolor {darkeryellow}{p_G(x)} \log \left ( \frac {1}{2} \cdot \frac {\textcolor {darkeryellow}{p_G(x)}}{\frac {\textcolor {darkred}{p_{\text {data}}(x)} + \textcolor {darkeryellow}{p_G(x)}}{2}} \right ) dx \Bigg ) \end {align*}

Using the logarithmic identity \( \log (a \cdot b) = \log a + \log b \), we separate the fraction \( \frac {1}{2} \) from the ratio of distributions. Note that \( \log (1/2) = -\log 2 \):

\begin {align*} = \min _{\textcolor {darkorange}{G}} \Bigg ( & \int _{\mathcal {X}} \textcolor {darkred}{p_{\text {data}}(x)} \left [ \log \left ( \frac {\textcolor {darkred}{p_{\text {data}}(x)}}{m(x)} \right ) - \log 2 \right ] dx \\ + & \int _{\mathcal {X}} \textcolor {darkeryellow}{p_G(x)} \left [ \log \left ( \frac {\textcolor {darkeryellow}{p_G(x)}}{m(x)} \right ) - \log 2 \right ] dx \Bigg ) \end {align*}

We now distribute the integrals. Since \( \textcolor {darkred}{p_{\mbox{data}}} \) and \( \textcolor {darkeryellow}{p_G} \) are valid probability distributions, they integrate to 1. Therefore, the constant terms \( -\log 2 \) sum to \( -2\log 2 = -\log 4 \). The remaining integrals are, by definition, KL divergences:

\begin {align*} = \min _{\textcolor {darkorange}{G}} \Bigg ( KL\left ( \textcolor {darkred}{p_{\text {data}}} \Big \| \frac {\textcolor {darkred}{p_{\text {data}}} + \textcolor {darkeryellow}{p_G}}{2} \right ) + KL\left ( \textcolor {darkeryellow}{p_G} \Big \| \frac {\textcolor {darkred}{p_{\text {data}}} + \textcolor {darkeryellow}{p_G}}{2} \right ) - \log 4 \Bigg ) \end {align*}

Introducing the Jensen–Shannon Divergence (JSD) The expression inside the minimization is related to the Jensen–Shannon Divergence (JSD), which measures the similarity between two probability distributions. Unlike KL divergence, JSD is symmetric and bounded. It is defined as: \[ JSD(p, q) = \frac {1}{2} KL\left ( p \Big \| \frac {p + q}{2} \right ) + \frac {1}{2} KL\left ( q \Big \| \frac {p + q}{2} \right ) \]

Final Result: Objective Minimizes JSD Substituting the JSD definition into our derived expression, the GAN training objective reduces to: \begin {align*} \min _{\textcolor {darkorange}{G}} C(\textcolor {darkorange}{G}) = \min _{\textcolor {darkorange}{G}} \left ( 2 \cdot JSD\left ( \textcolor {darkred}{p_{\text {data}}}, \textcolor {darkeryellow}{p_G} \right ) - {\log 4} \right ) \end {align*}

Interpretation:

- 1.

- The term \( -\log 4 \) represents the value of the game when the generator is perfect (confusion). Since \( \log 4 = 2 \log 2 \), this corresponds to the discriminator outputting \( 0.5 \) (uncertainty) for both real and fake samples: \( \log (0.5) + \log (0.5) = -\log 4 \).

- 2.

- Since \( JSD(p, q) \geq 0 \) with equality if and only if \( p = q \), the global minimum is achieved exactly when: \[ \textcolor {darkeryellow}{p_G(x)} = \textcolor {darkred}{p_{\mbox{data}}(x)} \]

This completes the proof: under idealized conditions (infinite capacity discriminator), the minimax game forces the generator to perfectly recover the data distribution.

Summary \begin {align*} \text {Optimal discriminator:} \quad &\textcolor {lightblue}{D}^{*}_{\textcolor {darkorange}{G}}(x) = \frac {\textcolor {darkred}{p_{\text {data}}(x)}}{\textcolor {darkred}{p_{\text {data}}(x)} + \textcolor {darkeryellow}{p_G(x)}} \\ \text {Global minimum:} \quad &\textcolor {purple}{p_G(x)} = \textcolor {darkred}{p_{\text {data}}(x)} \end {align*}

Important Caveats and Limitations of the Theoretical Result The optimality result derived above provides a crucial theoretical anchor: it guarantees that the minimax objective is statistically meaningful, identifying the data distribution as the unique global optimum. However, bridging the gap between this idealized theory and practical deep learning requires navigating several critical limitations.

-

Idealized Functional Optimization vs. Parameterized Networks. The derivation treats the discriminator \( D \) (and implicitly the generator \( G \)) as ranging over the space of all measurable functions. This ”non-parametric” or ”infinite capacity” assumption is what allows us to solve the inner maximization problem \(\max _D V(G,D)\) pointwise for every \( x \), yielding the closed-form \( D_G^* \).

In practice, we optimize over restricted families of functions parameterized by neural network weights, \( D_\phi \) and \( G_\theta \). The shared weights in a network introduce coupling between outputs—changing parameters to update \( D(x_1) \) inevitably affects \( D(x_2) \). Consequently: (i) The network family may not be expressive enough to represent the sharp, pointwise optimal discriminator \( D_G^* \); and (ii) Even if representable, the non-convex optimization landscape of the parameters may prevent gradient descent from finding it. Thus, the theorem proves that the game has the correct solution, not that a specific architecture trained with SGD will necessarily reach it.

-

The “Manifold Problem” and Vanishing Gradients. The JSD interpretation relies on the assumption that \( p_{\mbox{data}} \) and \( p_G \) have overlapping support with well-defined densities. In high-dimensional image spaces, however, distributions often concentrate on low-dimensional manifolds (e.g., the set of valid face images is a tiny fraction of the space of all possible pixel combinations).

Early in training, these real and generated manifolds are likely to be disjoint. In this regime, a sufficiently capable discriminator can separate the distributions perfectly, setting \( D(x) \approx 1 \) on real data and \( D(x) \approx 0 \) on fake data. Mathematically, this causes the Jensen–Shannon divergence to saturate at its maximum value (constant \(\log 2\)). Since the gradient of a constant is zero, the generator receives no informative learning signal to guide it toward the data manifold. This geometry is the primary cause of the vanishing gradient problem in the original GAN formulation and motivates alternative objectives (like the non-saturating heuristic or Wasserstein distance) designed to provide smooth gradients even when distributions do not overlap.

-

Existence vs. Convergence (Statics vs. Dynamics). The proof characterizes the static equilibrium of the game: if we reach a state where \( p_G = p_{\mbox{data}} \), we are at the global optimum. It says nothing about the dynamics of reaching that state.

GAN training involves finding a saddle point of a non-convex, non-concave objective using alternating stochastic gradient updates. Such dynamical systems are prone to pathologies that simple minimization avoids, including: (i) Limit cycles, where the generator and discriminator chase each other in circles (rotational dynamics) without improving; (ii) Divergence, where gradients grow uncontrollably; and (iii) Mode collapse, where the generator maps all latent codes to a single ”safe” output that fools the discriminator, satisfying the local objective but failing to capture the full diversity of the data distribution.

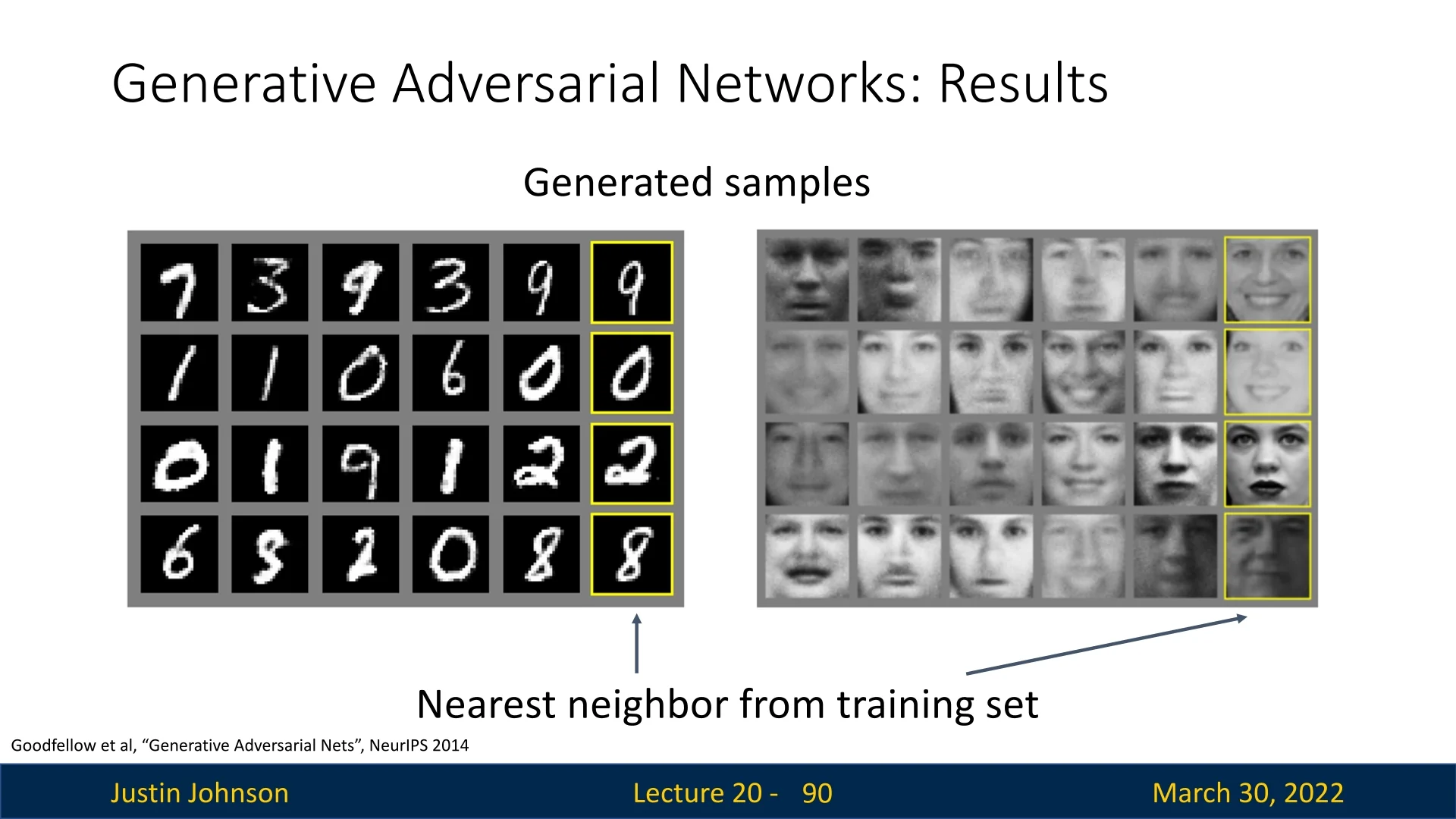

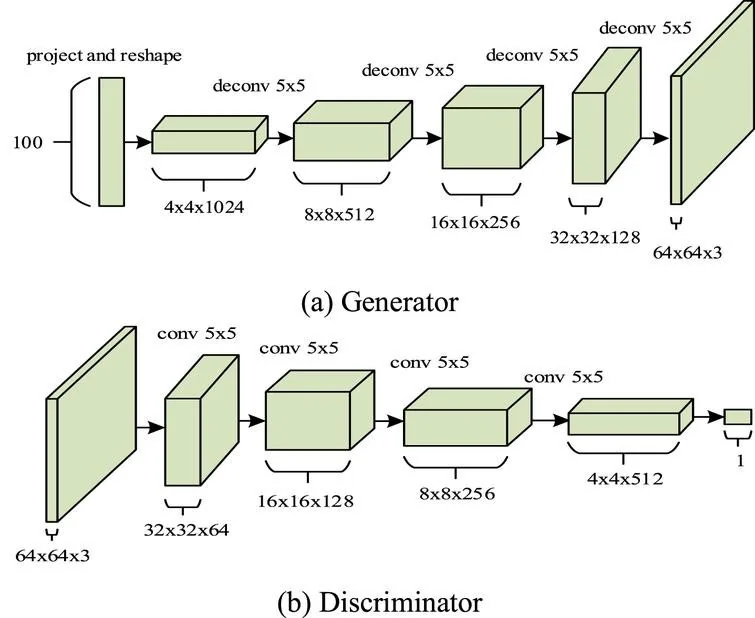

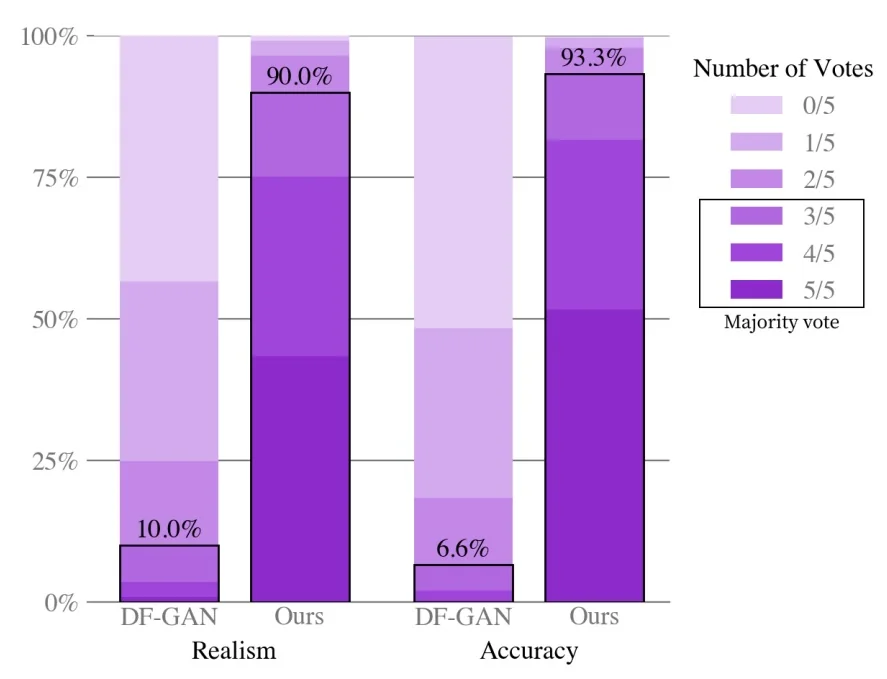

20.5 GANs in Practice: From Early Milestones to Modern Advances

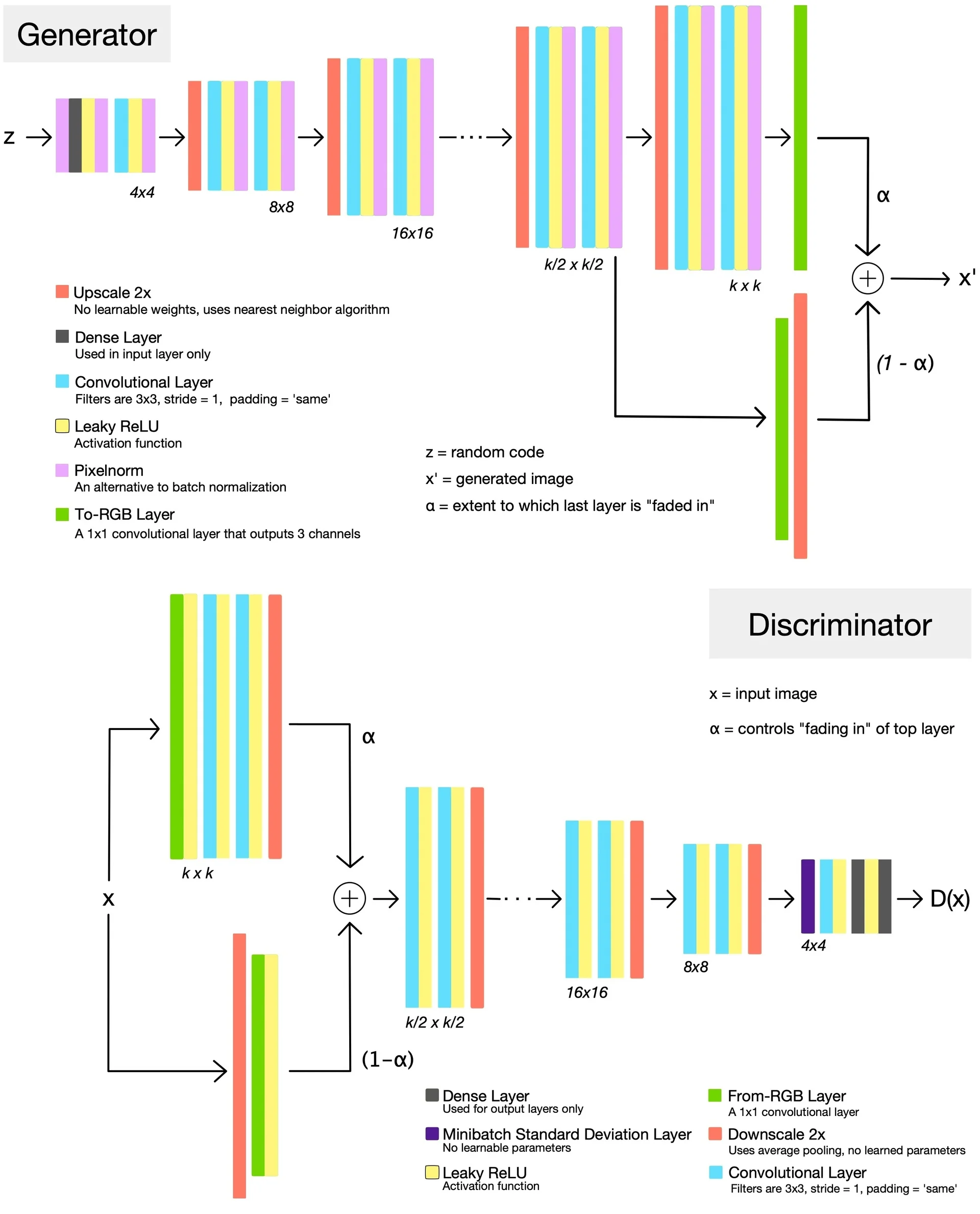

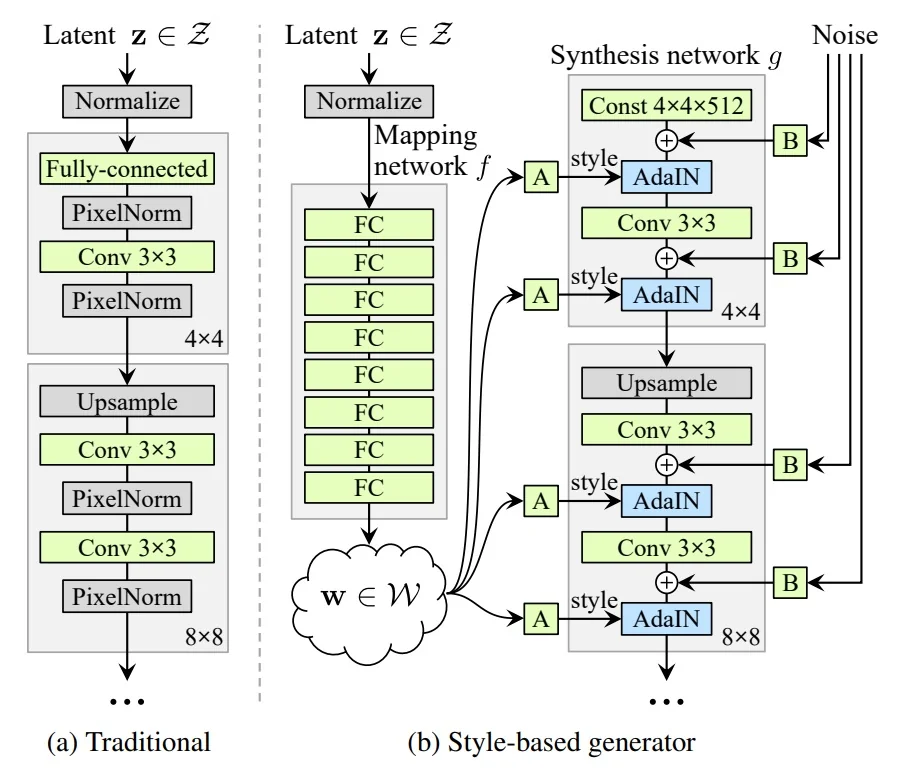

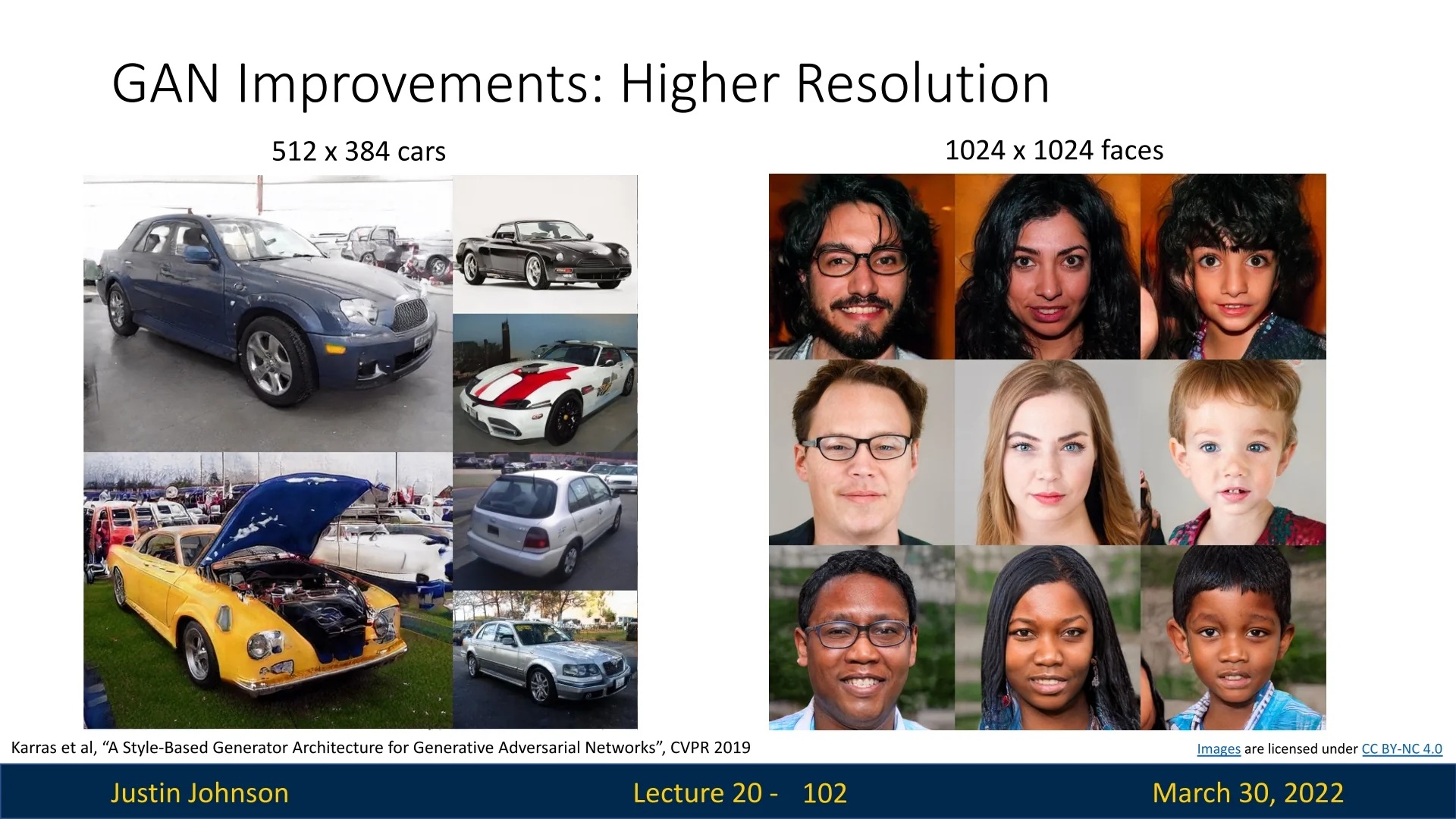

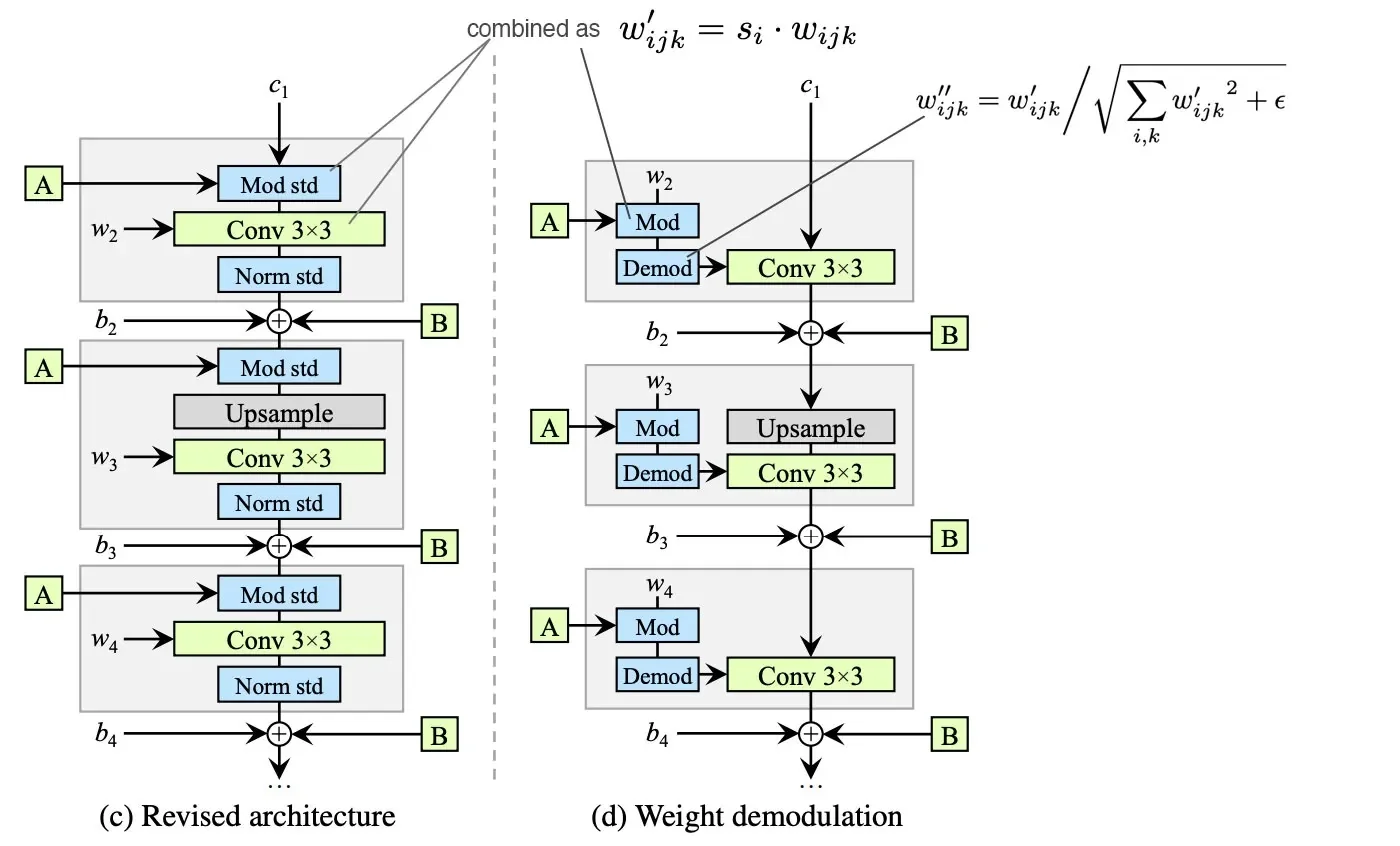

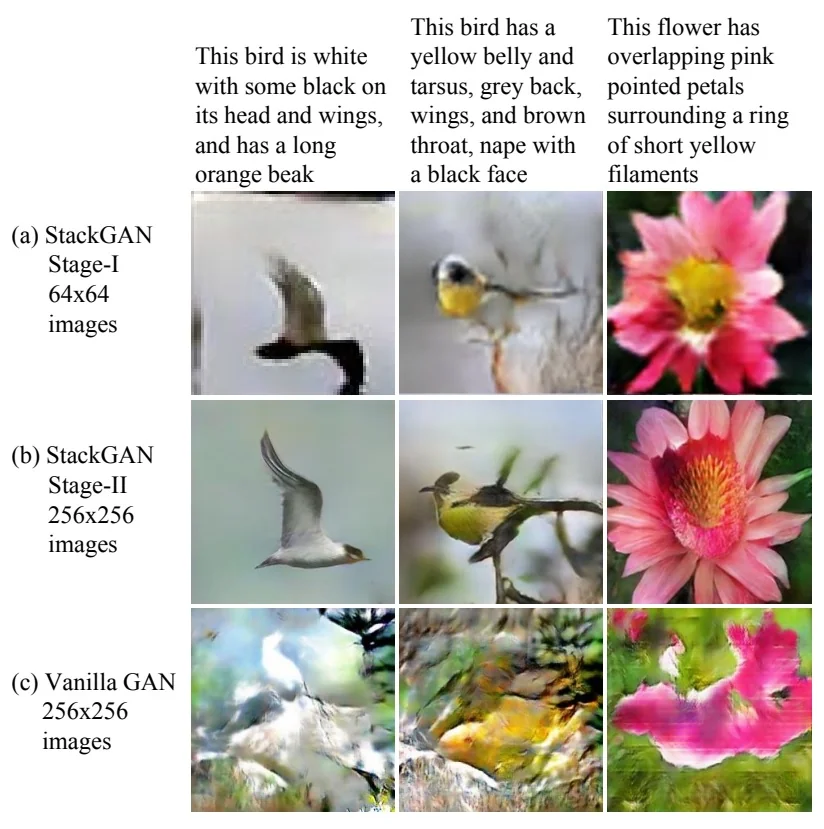

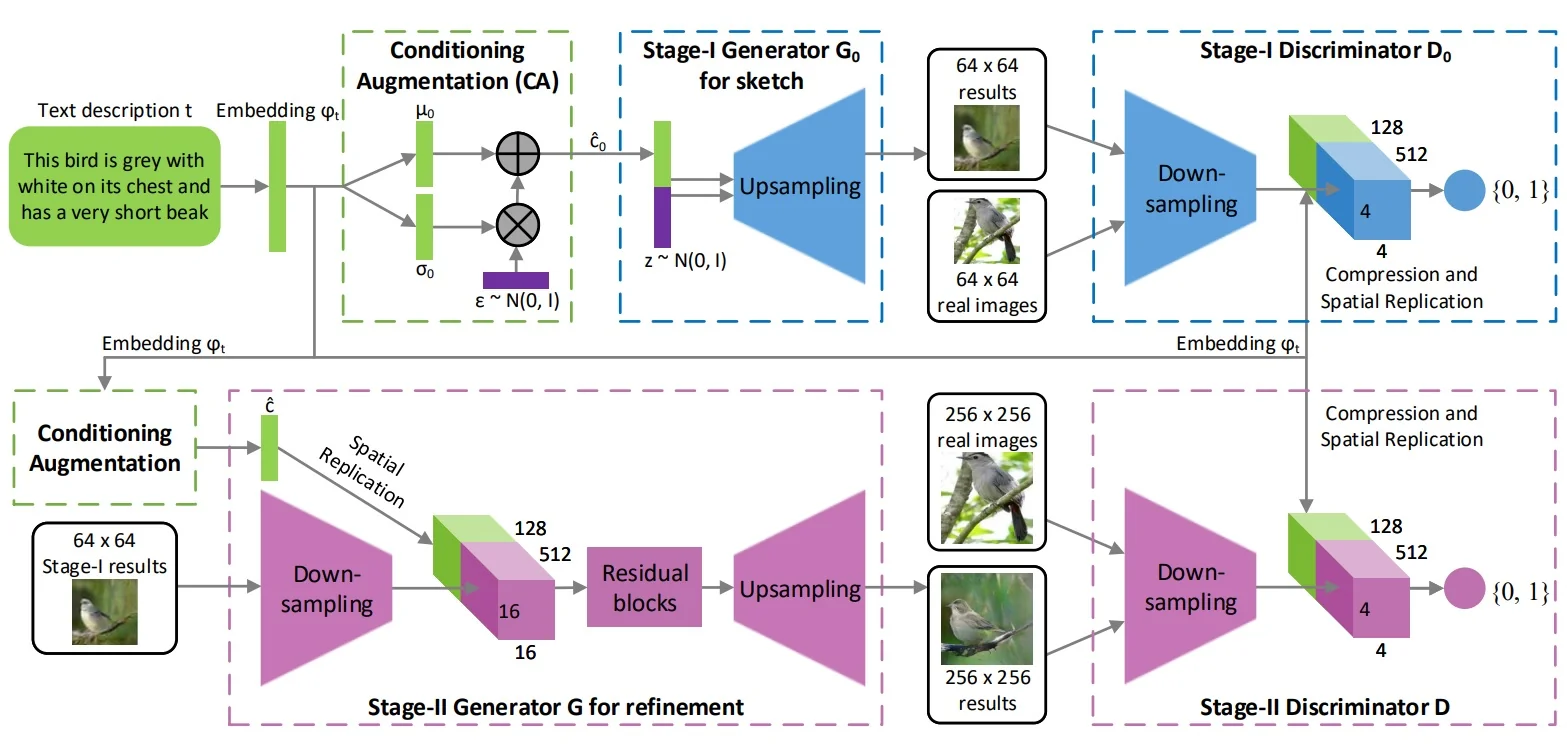

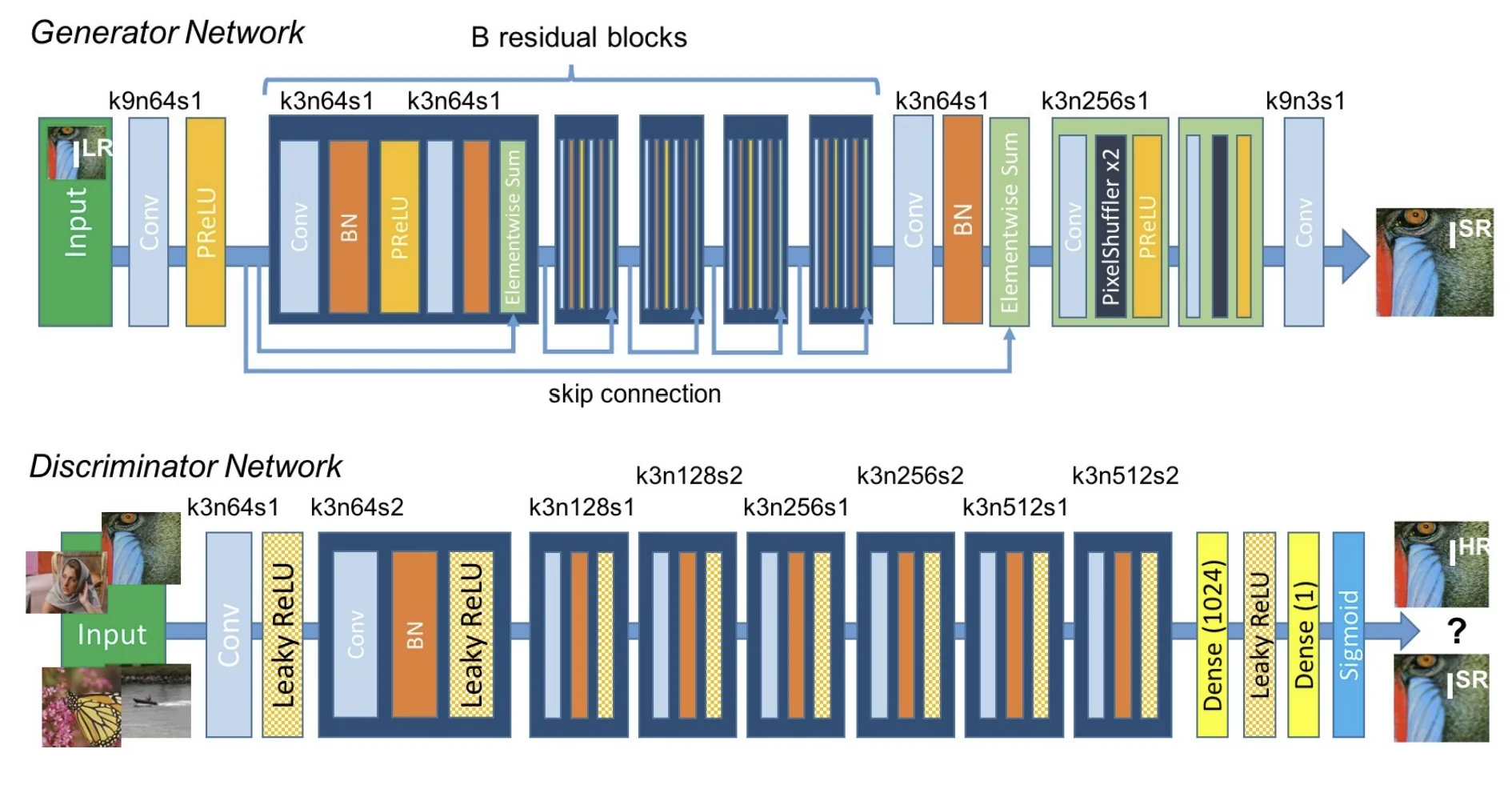

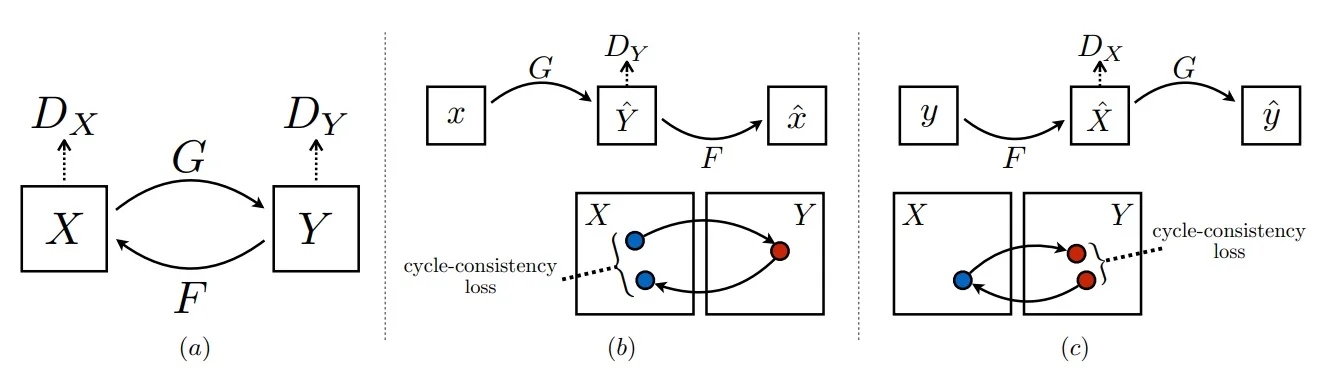

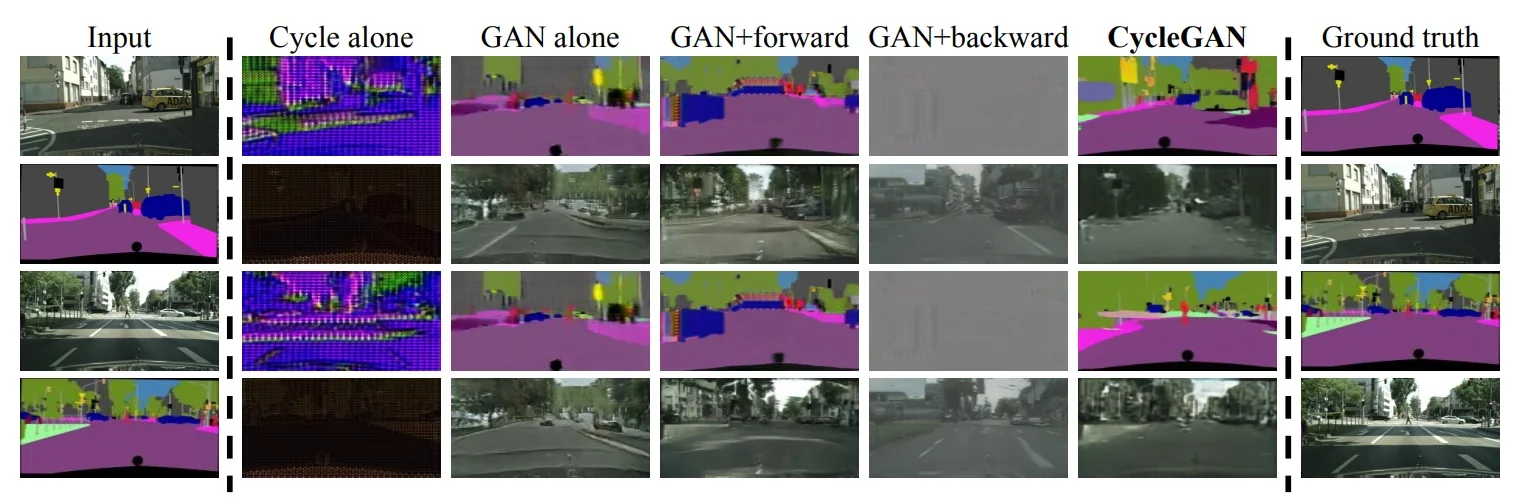

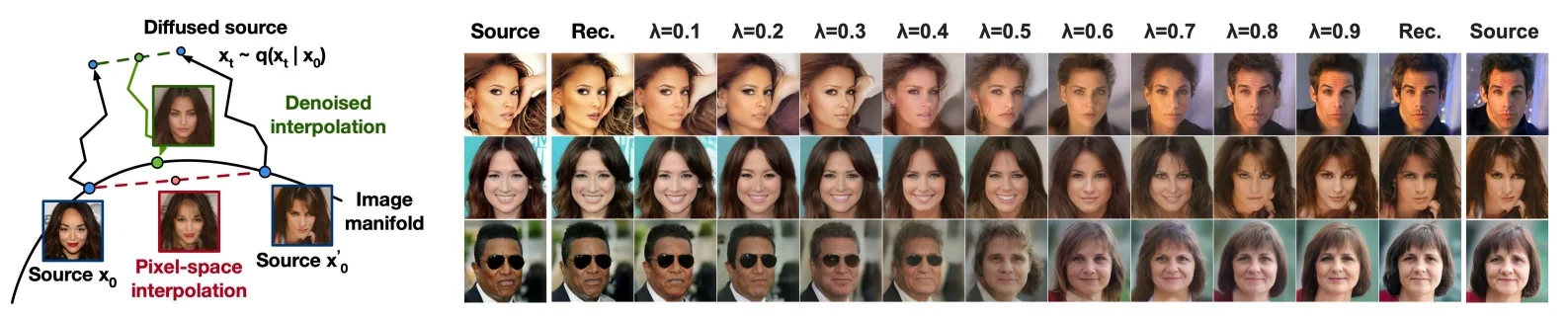

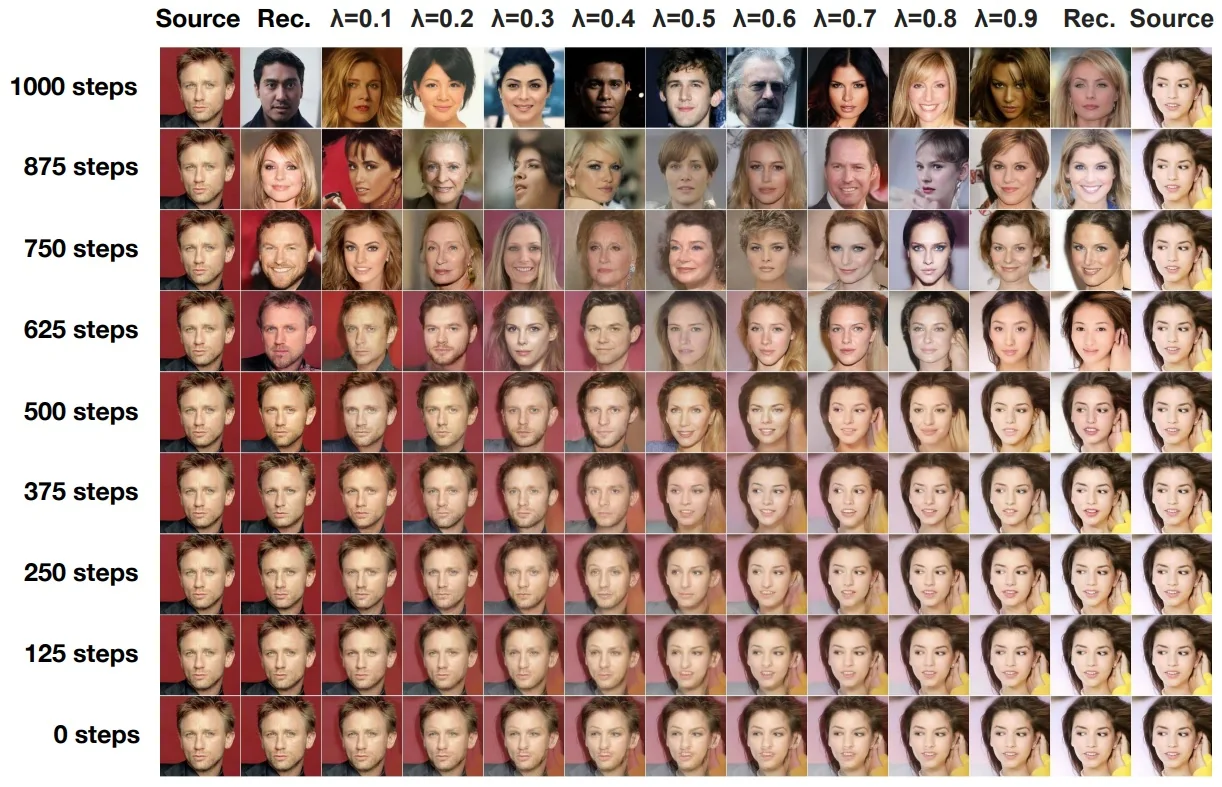

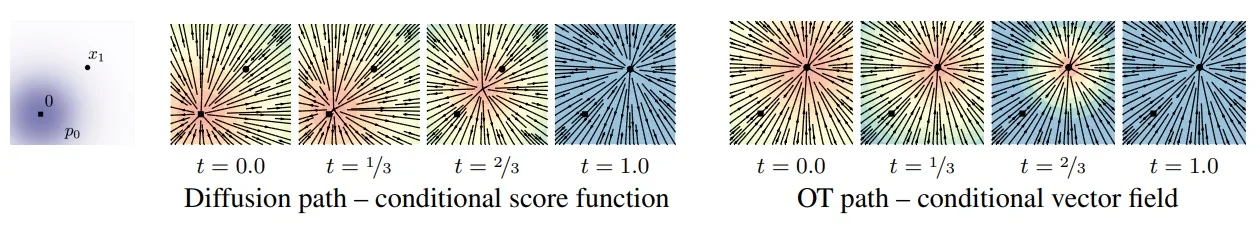

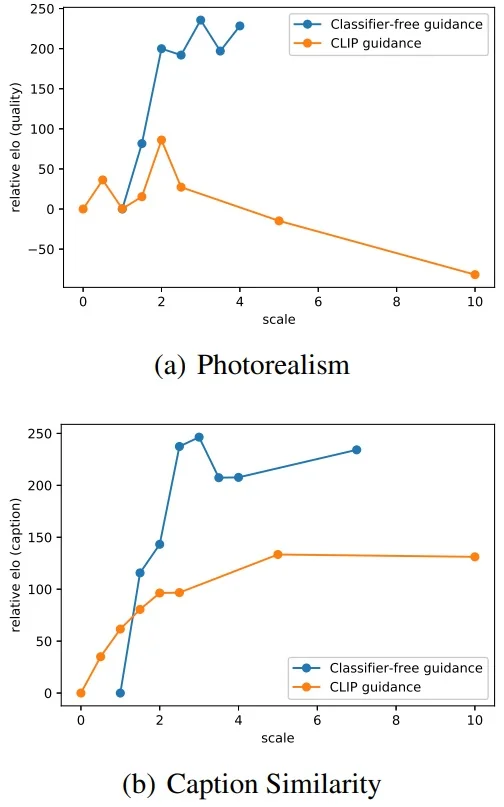

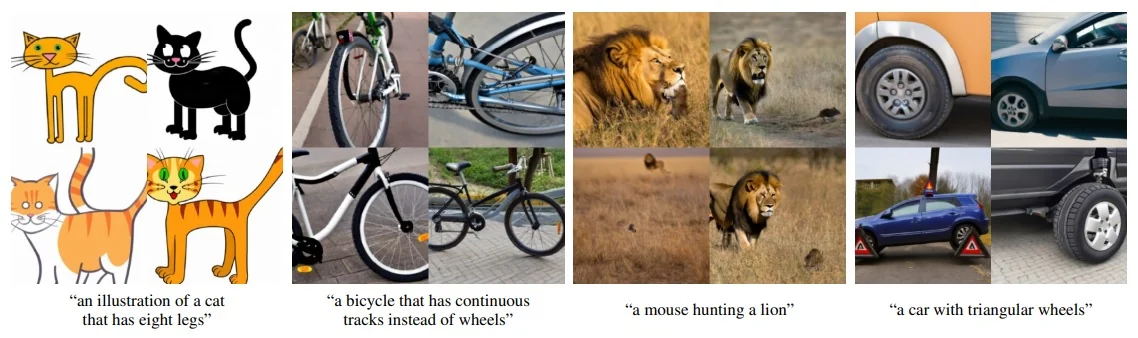

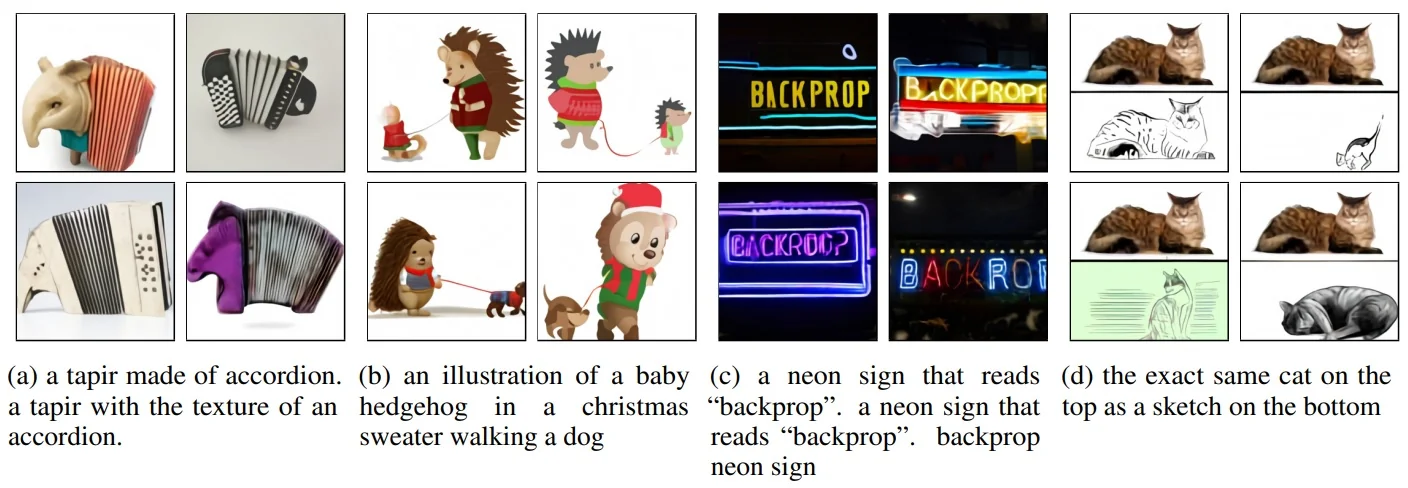

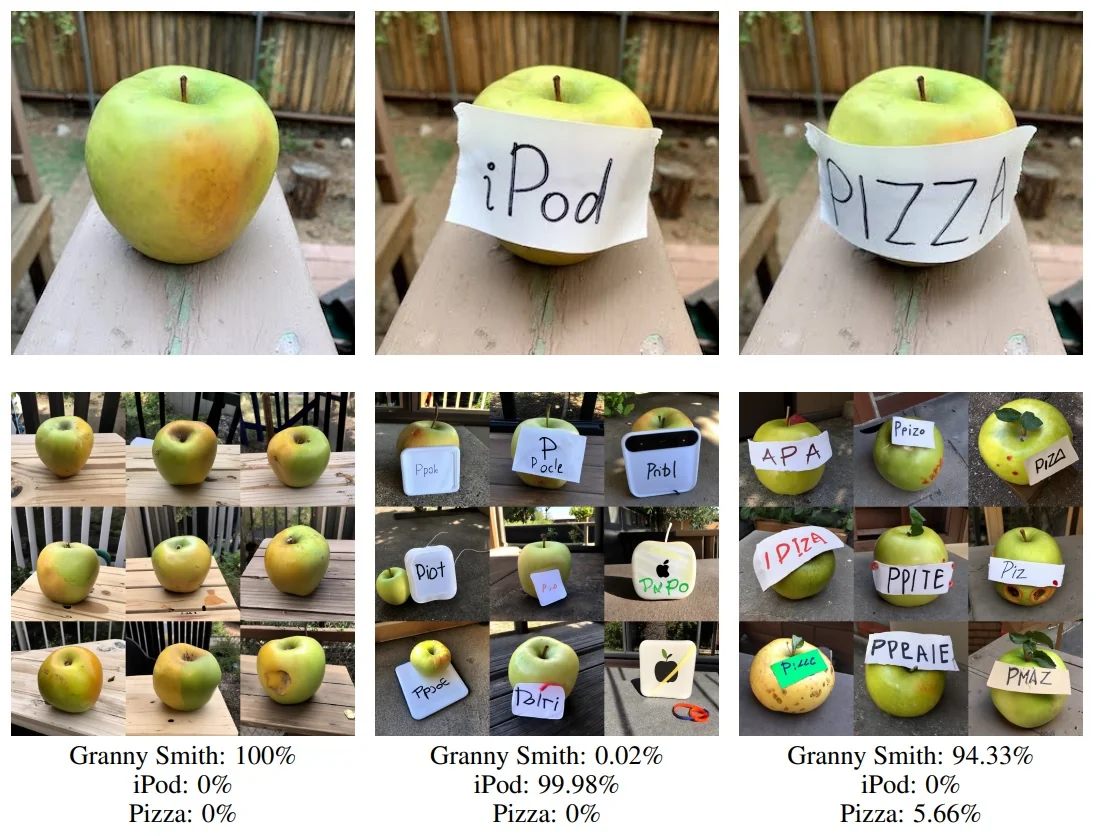

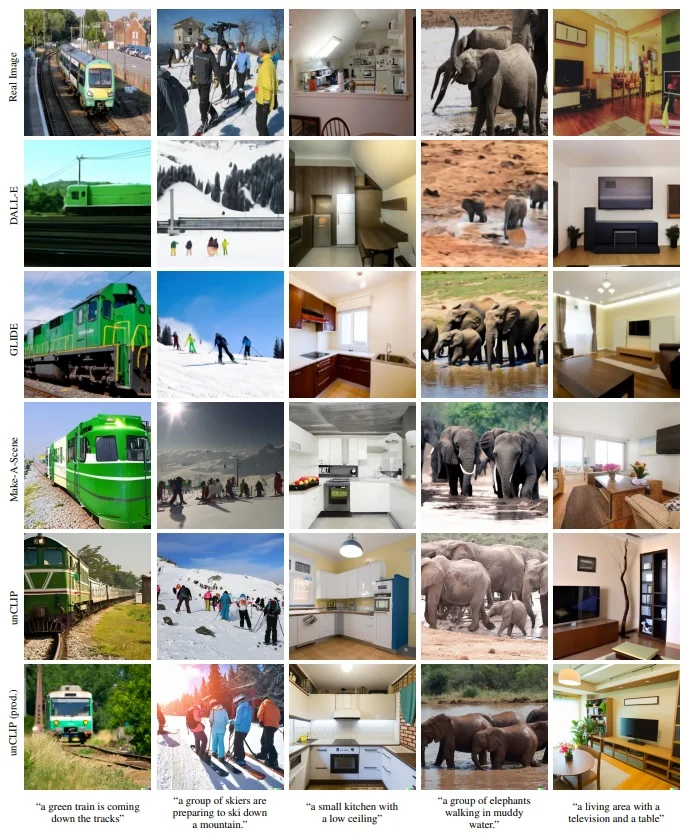

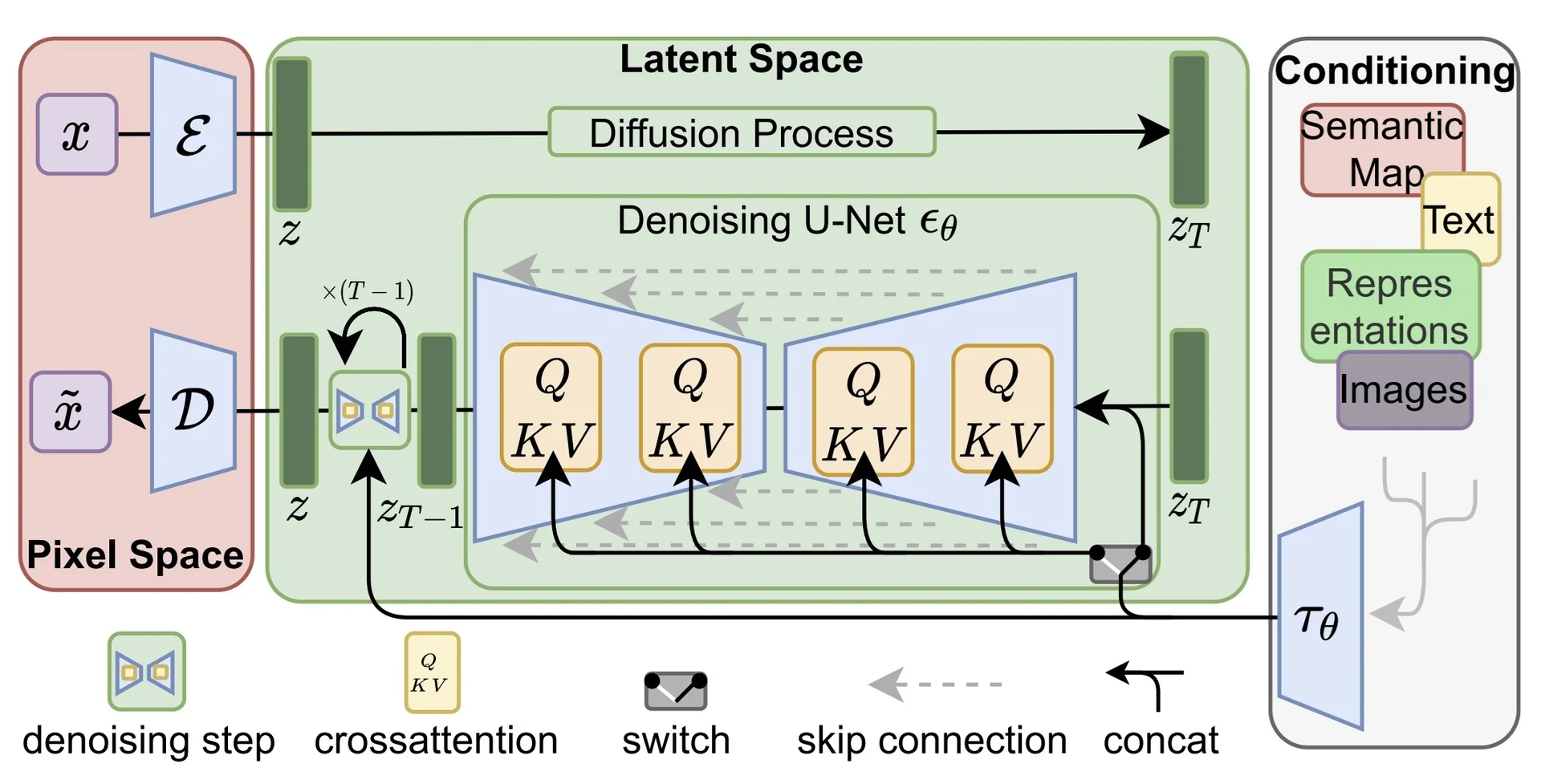

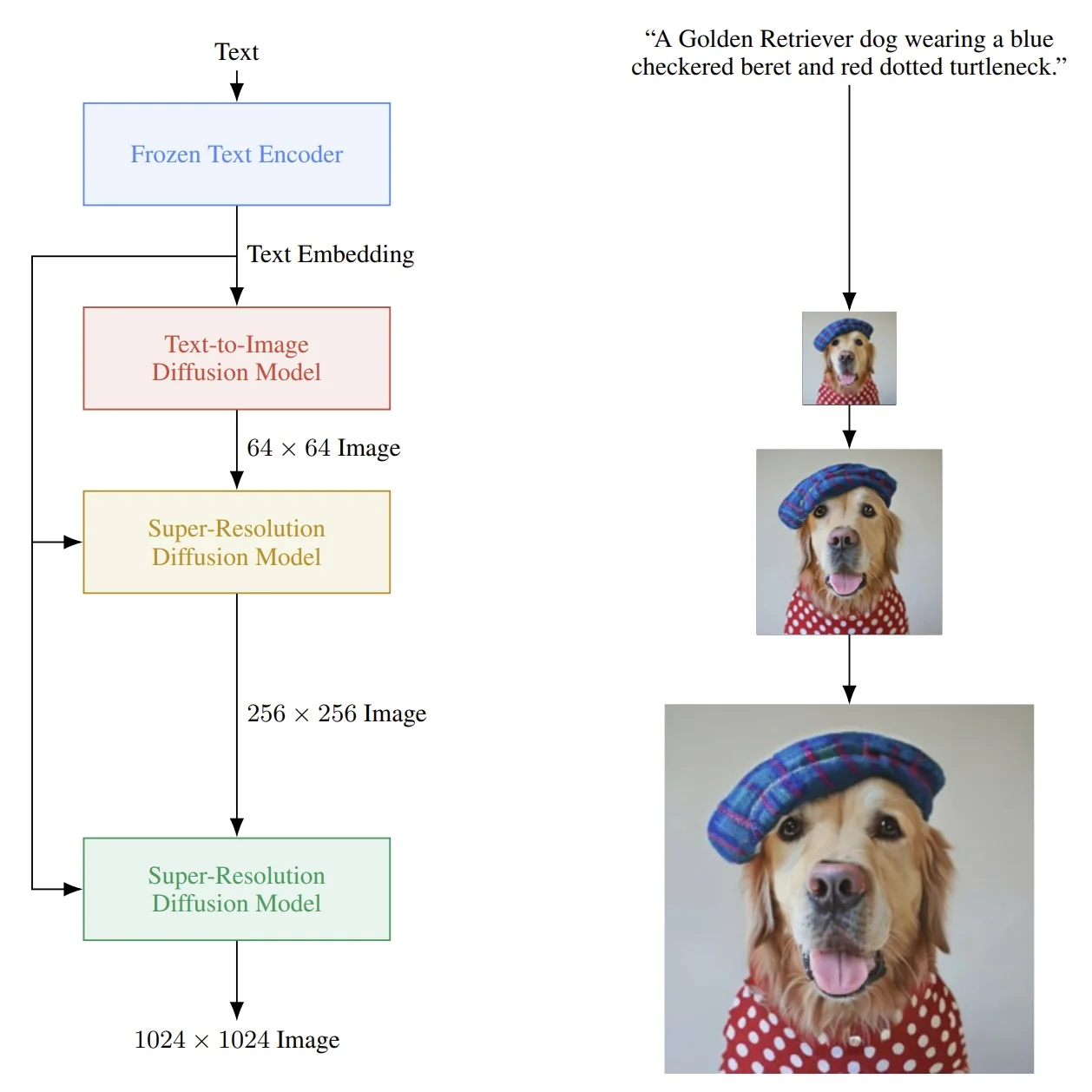

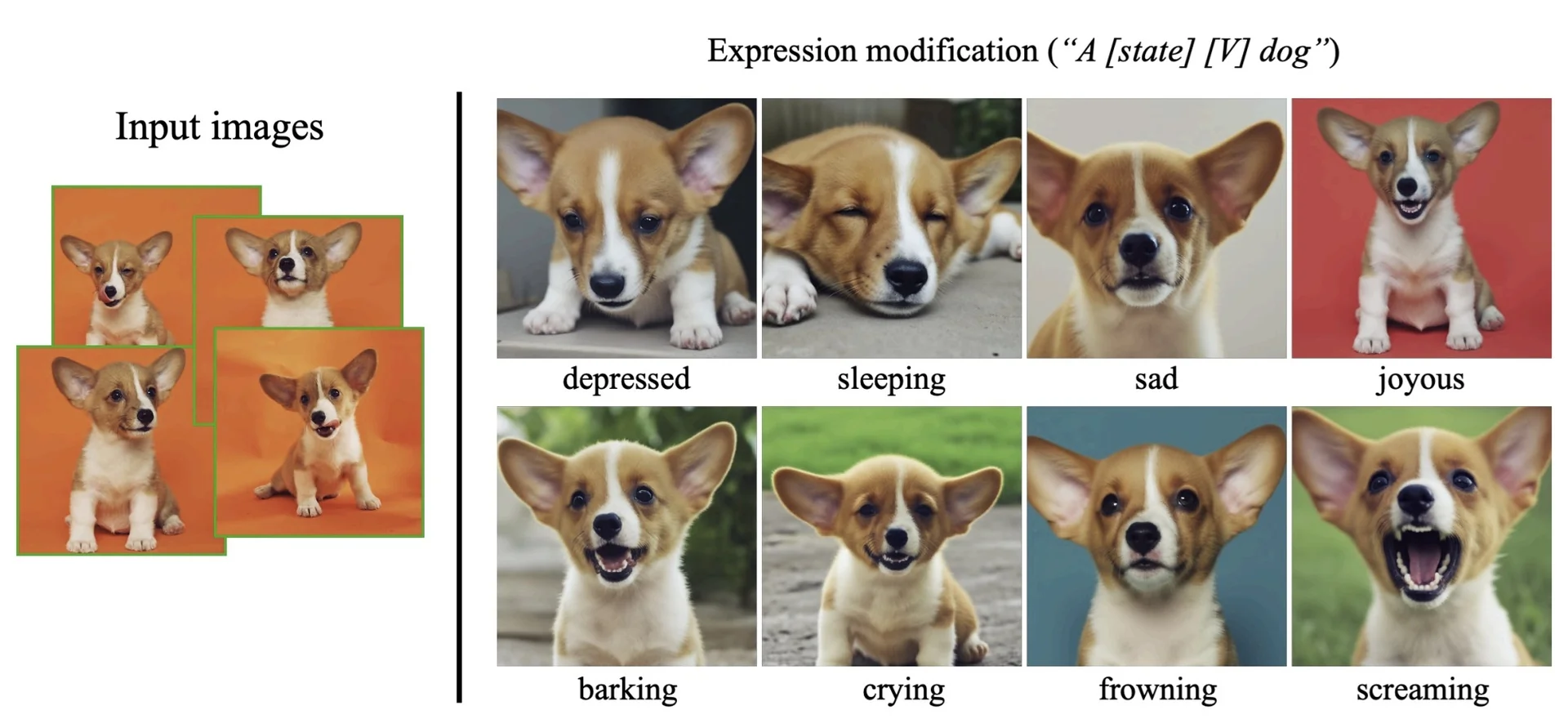

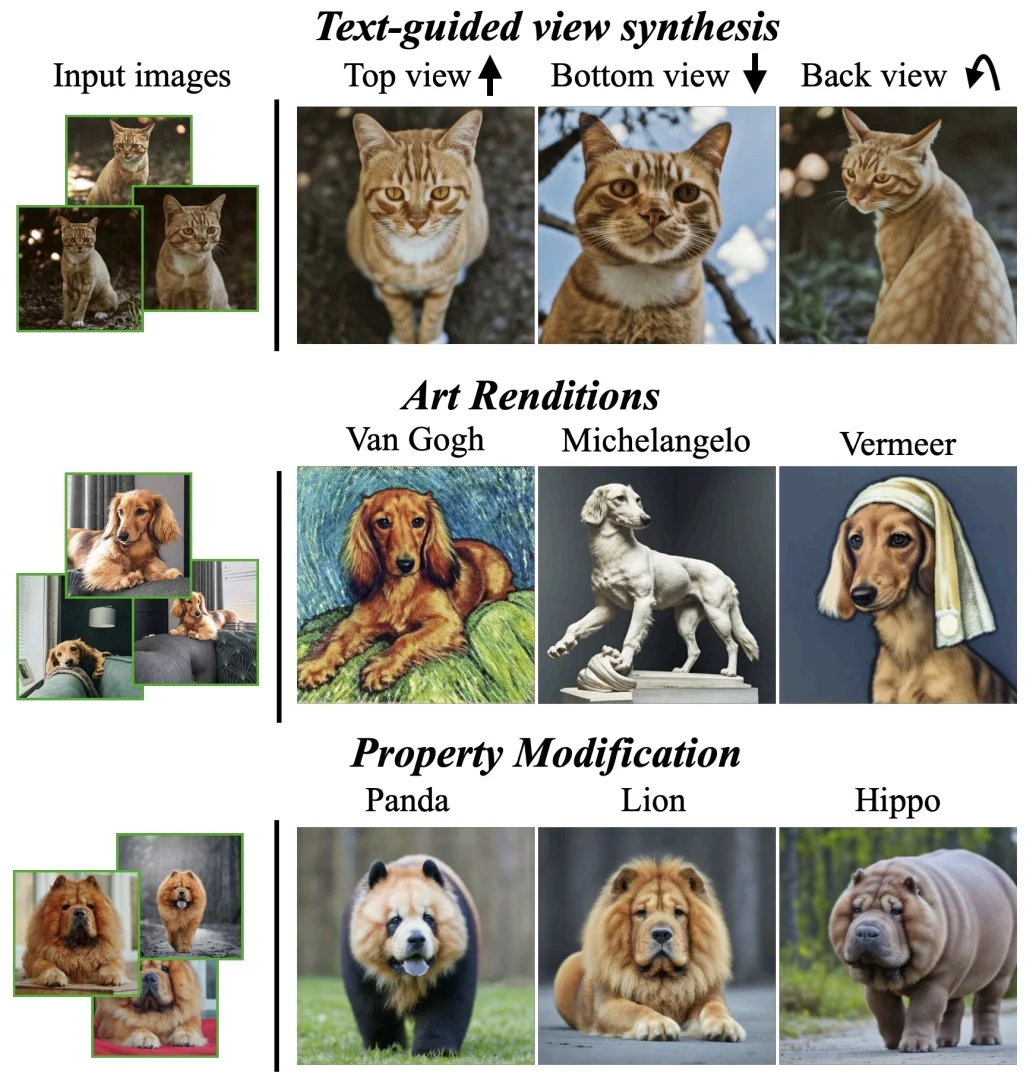

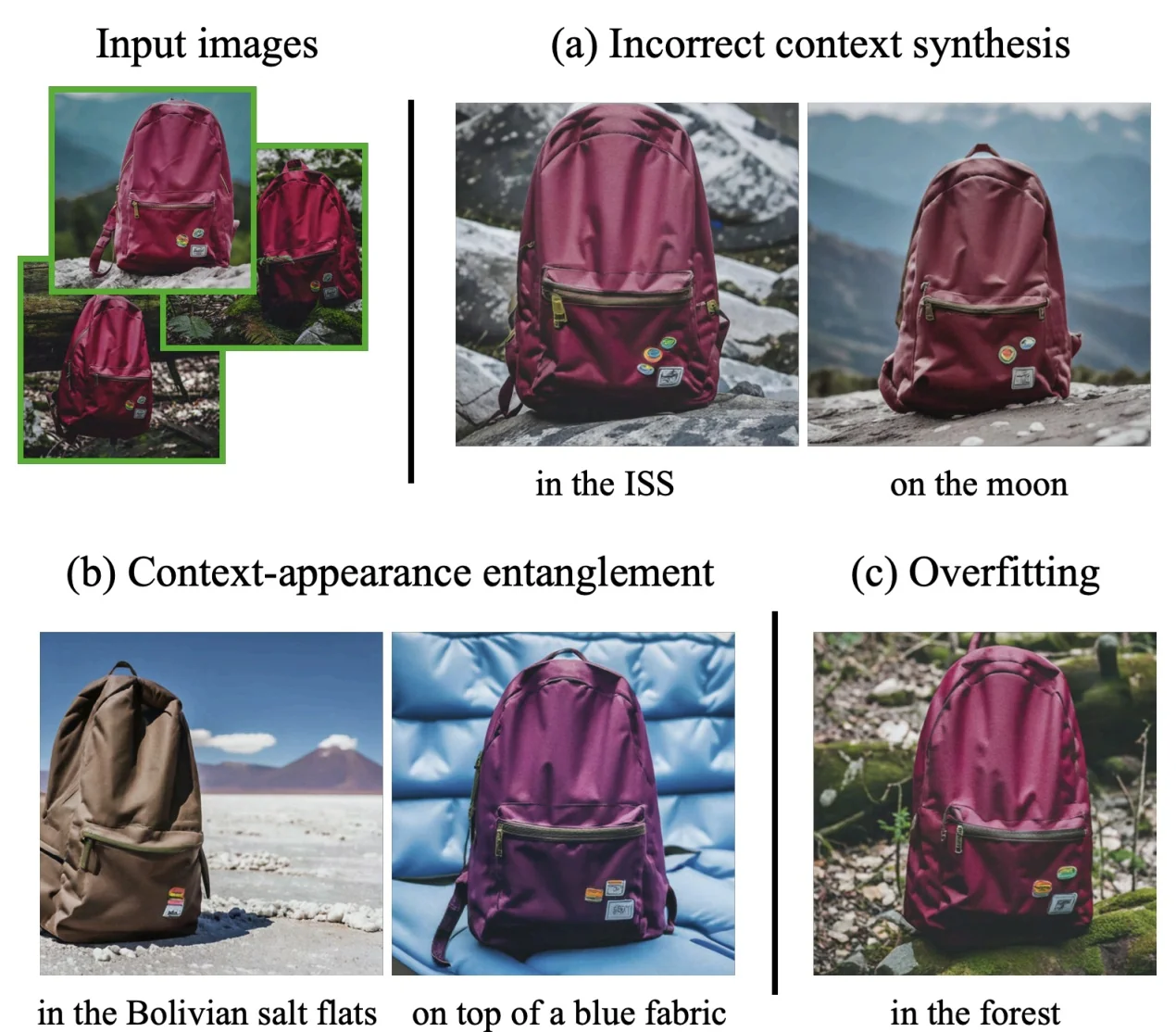

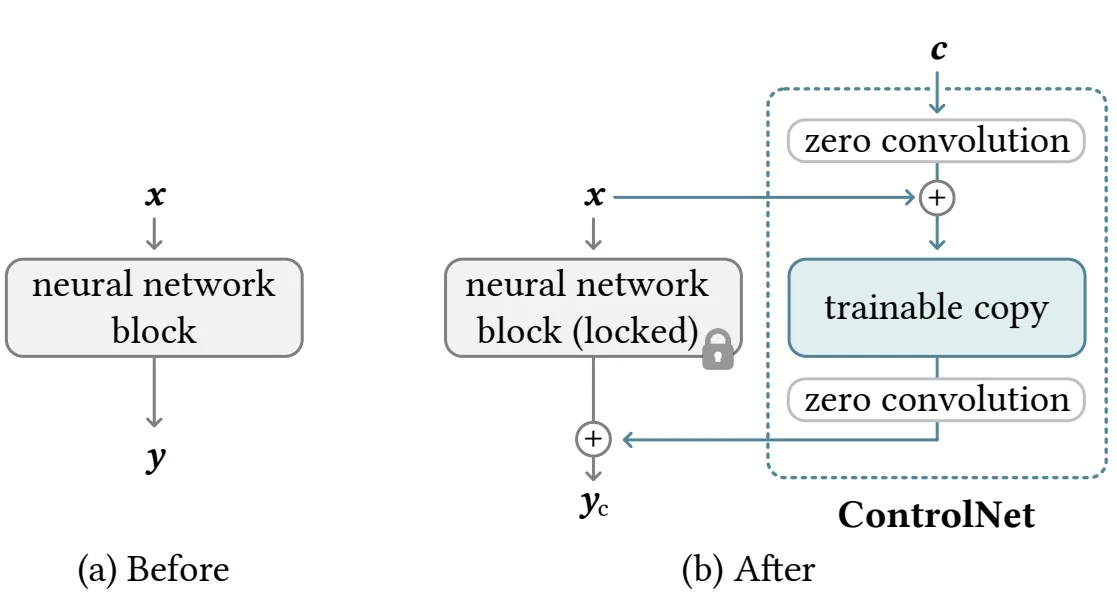

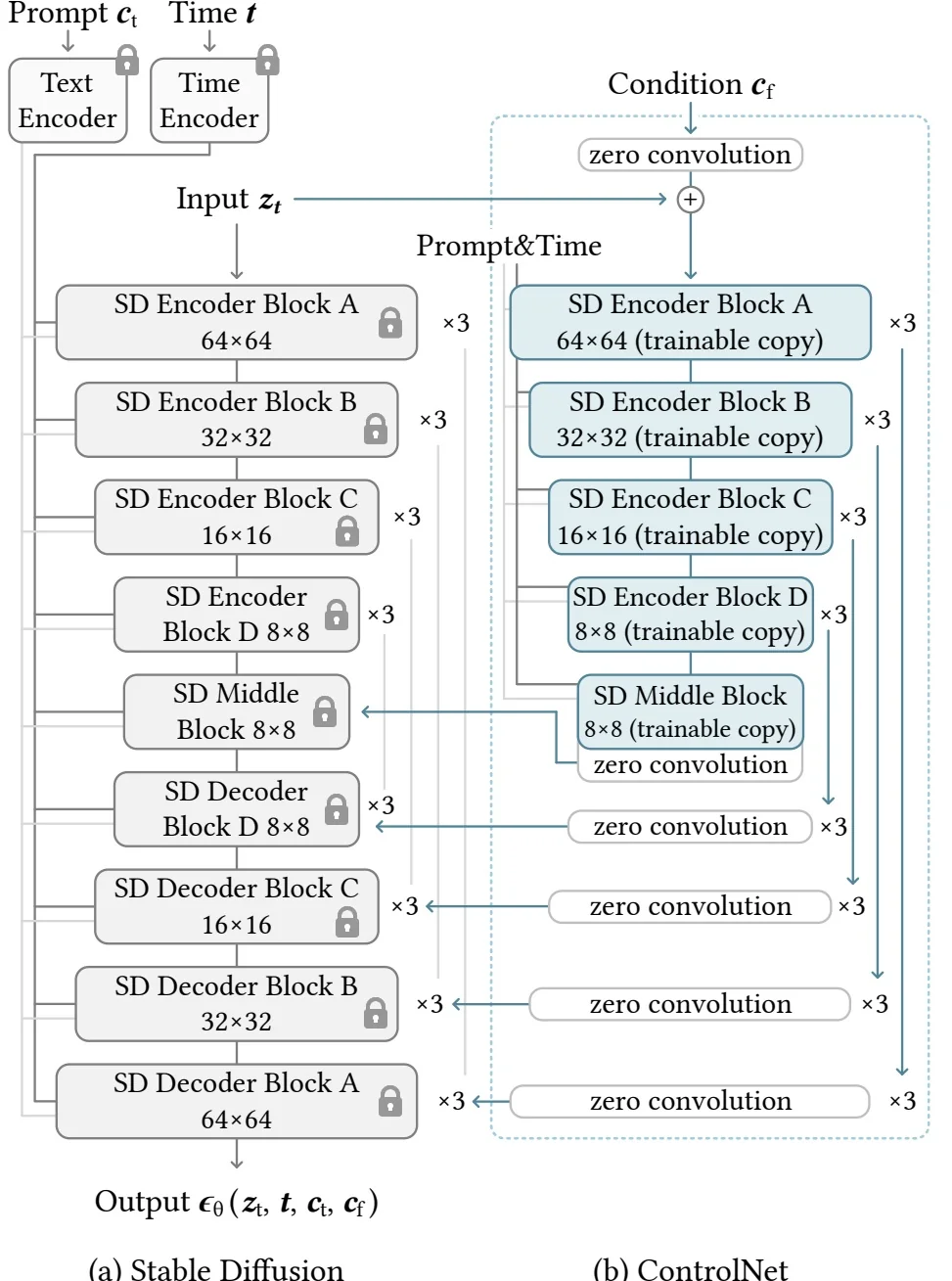

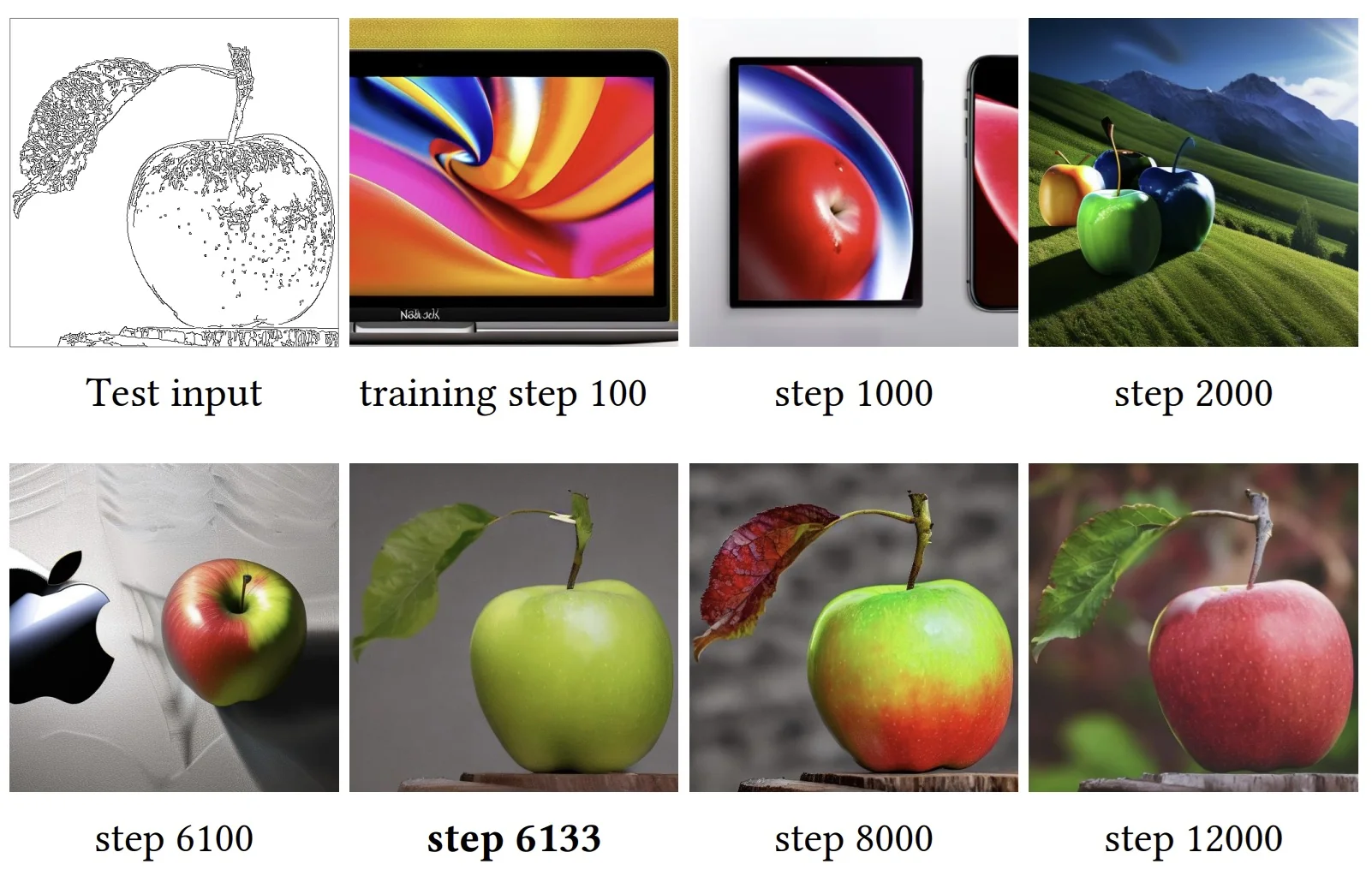

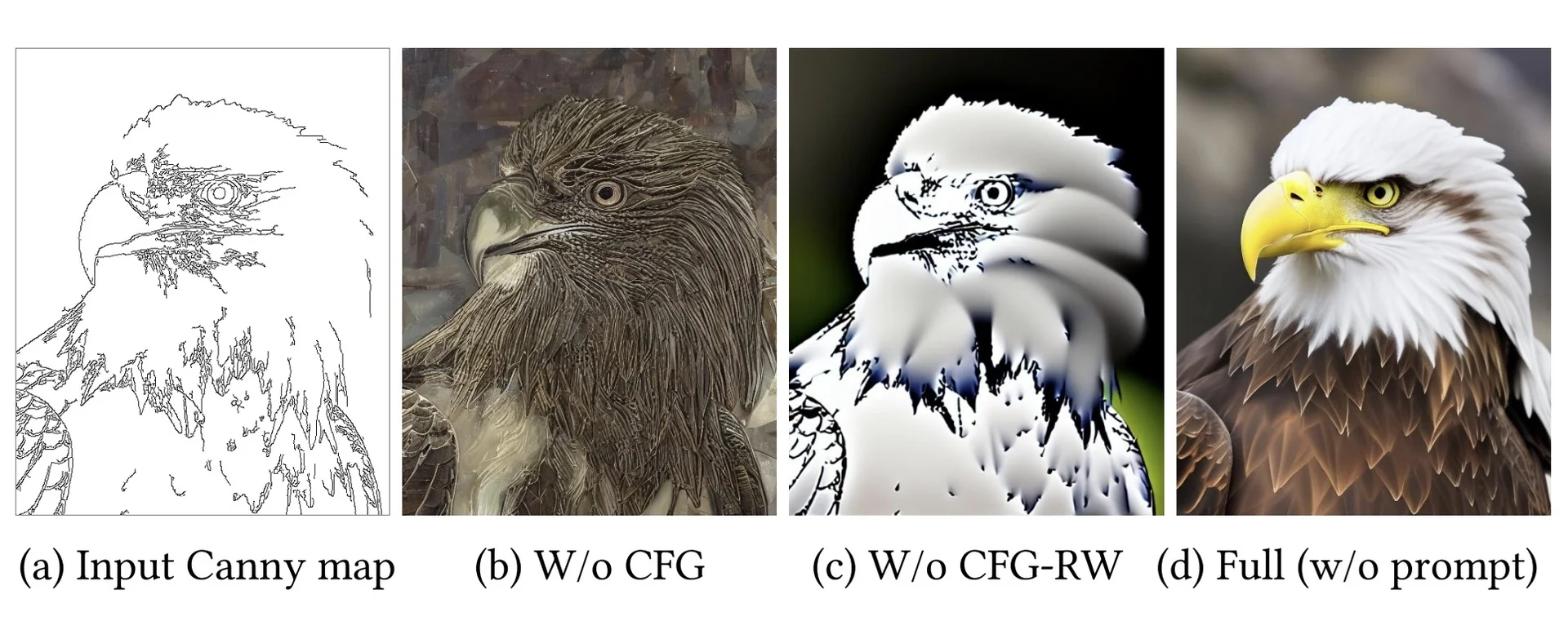

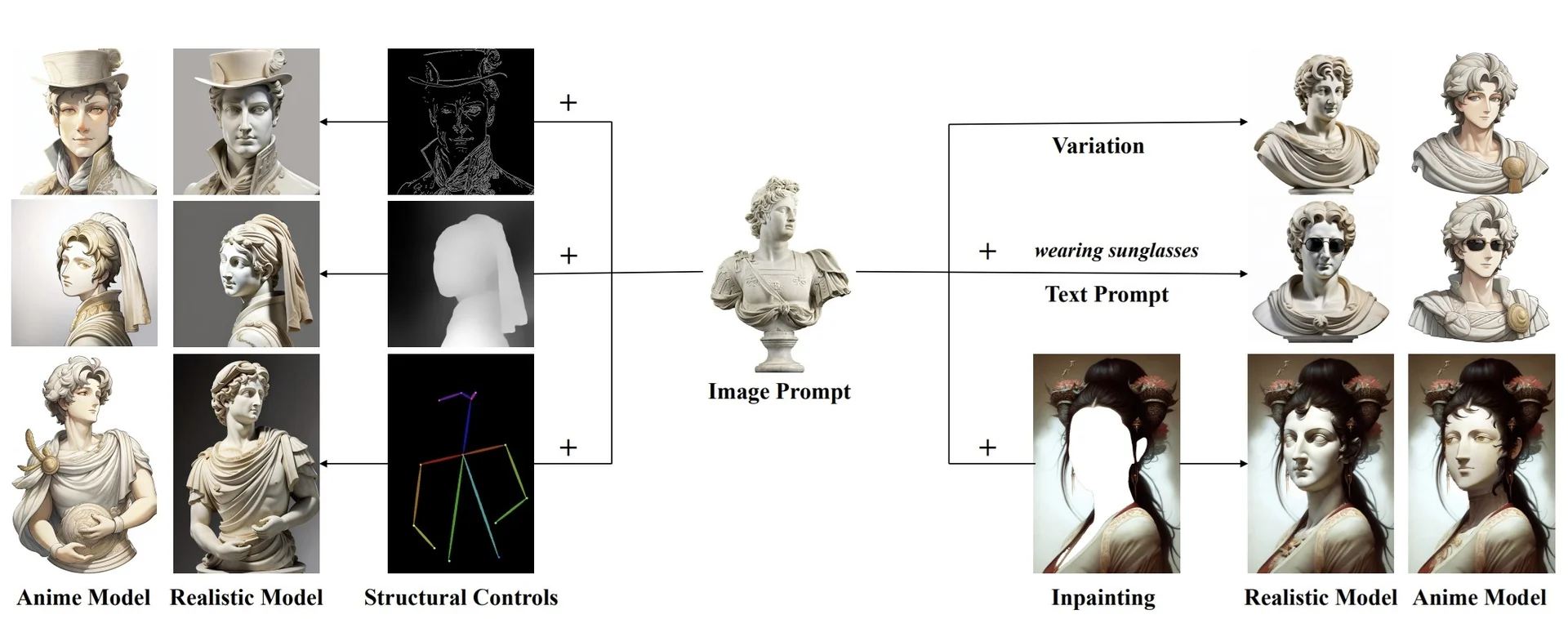

20.5.1 The Original GAN (2014)