Lecture 1: Course Introduction

This chapter presents my detailed lecture notes, designed to complement the material from the course. These notes build upon the lecture content, incorporating figures, examples, and concepts introduced by Justin Johnson in his lecture slides.

You can follow along with the lecture slides available here or watch the corresponding lecture video on YouTube. Together, these resources provide a comprehensive understanding of the topics covered.

1.1 Core Terms in the Field

A solid understanding of the fundamental terminology in artificial intelligence (AI) and its subfields is crucial for following this course, engaging with the lecture materials, and navigating the broader field of deep learning and computer vision. Defining these terms provides a shared foundation for deeper exploration and application, ensuring clarity as we delve into more advanced topics.

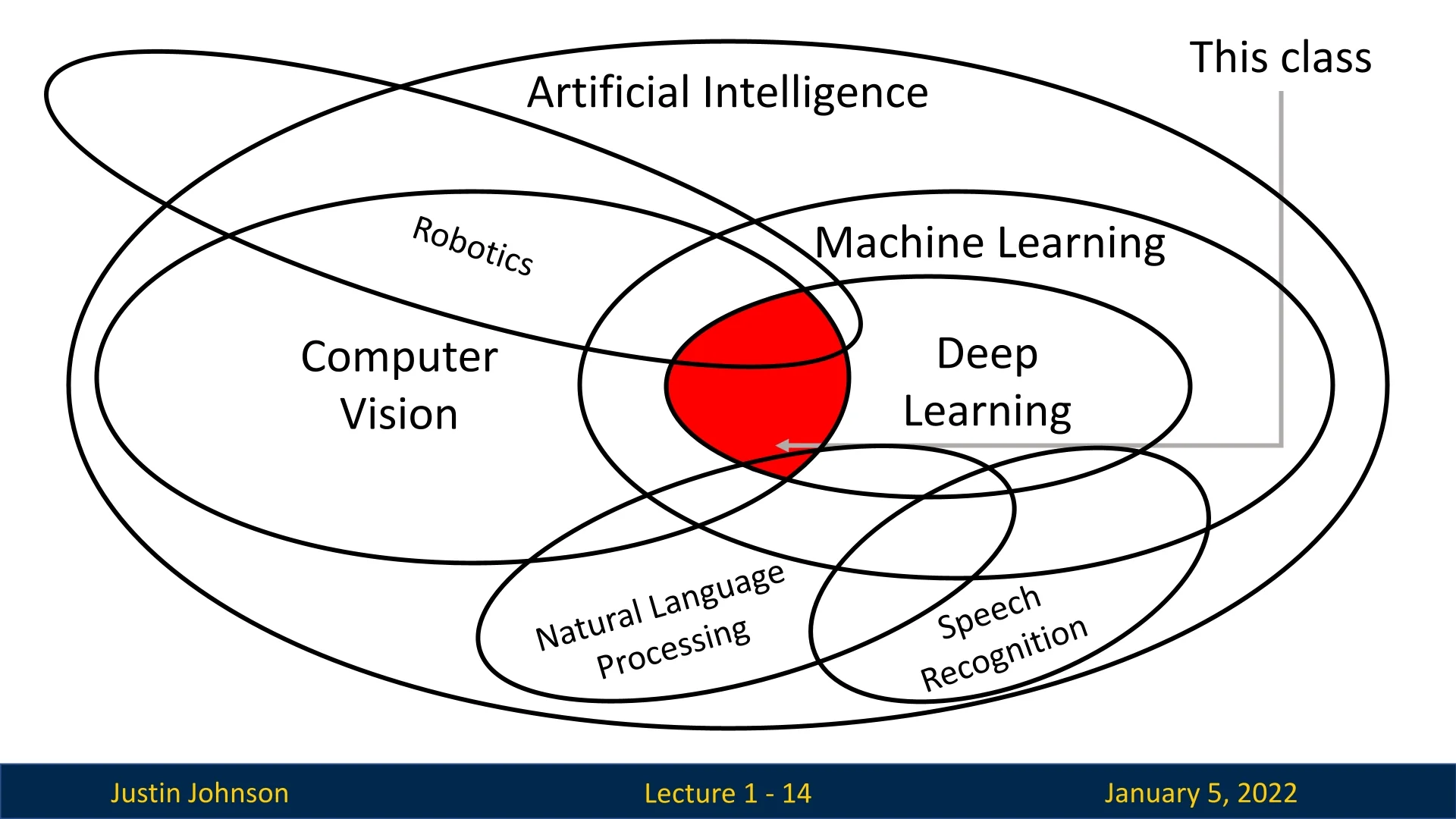

1.1.1 Artificial Intelligence (AI)

Definition 1.1 (Artificial Intelligence (AI)) The overarching field focused on creating systems capable of performing tasks that typically require human intelligence. These tasks include reasoning, decision-making, language understanding, and visual perception. AI encompasses a wide range of approaches, including symbolic logic, rule-based systems, and learning-based techniques, to address complex problems across diverse domains.

1.1.2 Machine Learning (ML)

Definition 1.2 (Machine Learning (ML)) A subset of AI that enables systems to learn from data and improve their performance on tasks without explicit programming. Machine learning relies on algorithms and statistical models to analyze data, identify patterns, and make predictions or decisions.

Popular techniques include:

- Supervised Learning: Models learn from labeled data, mapping inputs to desired outputs (e.g., classifying images into categories like cats and dogs).

- Unsupervised Learning: Models identify patterns and structures in unlabeled data (e.g., clustering similar images).

- Reinforcement Learning: Models learn to make sequential decisions by interacting with an environment to maximize rewards.

This course primarily focuses on supervised and unsupervised learning, which are widely applied in deep learning for computer vision.

1.1.3 Deep Learning (DL)

Definition 1.3 (Deep Learning (DL)) A specialized subset of machine learning characterized by hierarchical algorithms that process data through multiple layers. Each layer extracts increasingly abstract features, enabling systems to learn complex representations. For instance, in image analysis, early layers often identify edges and textures, while deeper layers detect objects and scenes. Deep learning has driven major advancements in fields like natural language processing, speech recognition, and computer vision.

1.1.4 Computer Vision (CV)

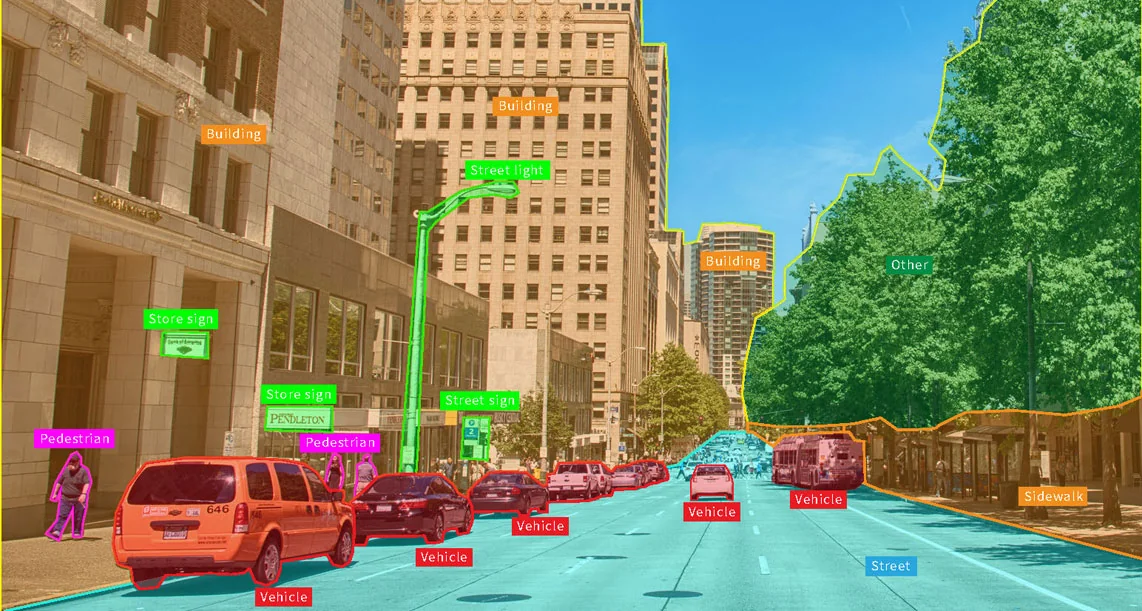

Definition 1.4 (Computer Vision (CV)) A domain within AI that focuses on enabling artificial systems to analyze, interpret, and process visual data, such as images and videos. CV intersects with, but is not a subset of, machine learning or deep learning. Instead, learning-based approaches like convolutional neural networks (CNNs) have become indispensable tools within CV, solving tasks such as image classification, object detection, and semantic segmentation. Applications are widespread, powering smartphone cameras, surveillance systems, autonomous vehicles, and robotics.

1.1.5 Connecting the Dots

The relationships between these terms highlight their interdependence:

- AI is the parent discipline encompassing all methods of creating intelligent systems.

- ML is a subset of AI, focusing on learning from data to improve performance.

- DL is a subset of ML, leveraging layered neural networks to solve complex problems.

- CV is a domain within AI that intersects with ML and DL, applying their techniques to visual data.

1.2 Why Study Deep Learning for Computer Vision?

Learning-based approaches have transformed computer vision by outperforming traditional algorithms in handling complex, real-world data. Unlike manual feature engineering, deep learning allows systems to automatically extract representations directly from data, making them more adaptable and effective. This shift has made Deep Learning for Computer Vision the dominant paradigm, enabling breakthroughs in areas like healthcare (e.g., disease detection through medical imaging), transportation (e.g., autonomous vehicles), and security (e.g., facial recognition). By leveraging the synergy of AI, ML, and DL, deep learning continues to drive innovation and solve increasingly sophisticated challenges across industries.

1.2.1 Motivation for Deep Learning in Computer Vision

Computer Vision (CV) is a transformative force in modern technology, enabling machines to perceive and interpret the world as humans do—or better. By leveraging deep learning, CV has revolutionized industries and unlocked groundbreaking capabilities, from the smartphone in your hand to the autonomous vehicles navigating our streets.

In healthcare, CV drives advancements in medical imaging, facilitating early disease detection and life-saving diagnostics. It powers safer, more efficient transportation through autonomous systems on the road. In agriculture, CV optimizes crop monitoring and pest detection, while in astronomy, it deciphers galaxy formations, expanding our understanding of the cosmos.

Beyond industry, CV impacts daily life—enhancing security with facial recognition, enriching entertainment with augmented reality, and revolutionizing commerce with smart retail solutions. Its potential to create a safer, healthier, and more connected world makes CV a compelling and impactful field, offering countless opportunities to shape the future.

1.3 Historical Milestones

This lecture offers a comprehensive journey through the evolution of computer vision, starting with its roots in neuroscience and progressing to its modern-day applications in artificial intelligence. The milestones covered are foundational to understanding the field, providing a historical perspective on the advancements that have shaped computer vision as we know it today. While many technical terms and concepts, such as convolutional neural networks (CNNs), vanishing gradients, recurrent neural networks (RNNs), long short-term memory (LSTM) networks, Transformers, and others, are briefly introduced, readers are encouraged not to feel deterred. Each of these topics will be explored in greater depth throughout the course and this summary, ensuring a thorough and accessible understanding of these pivotal ideas.

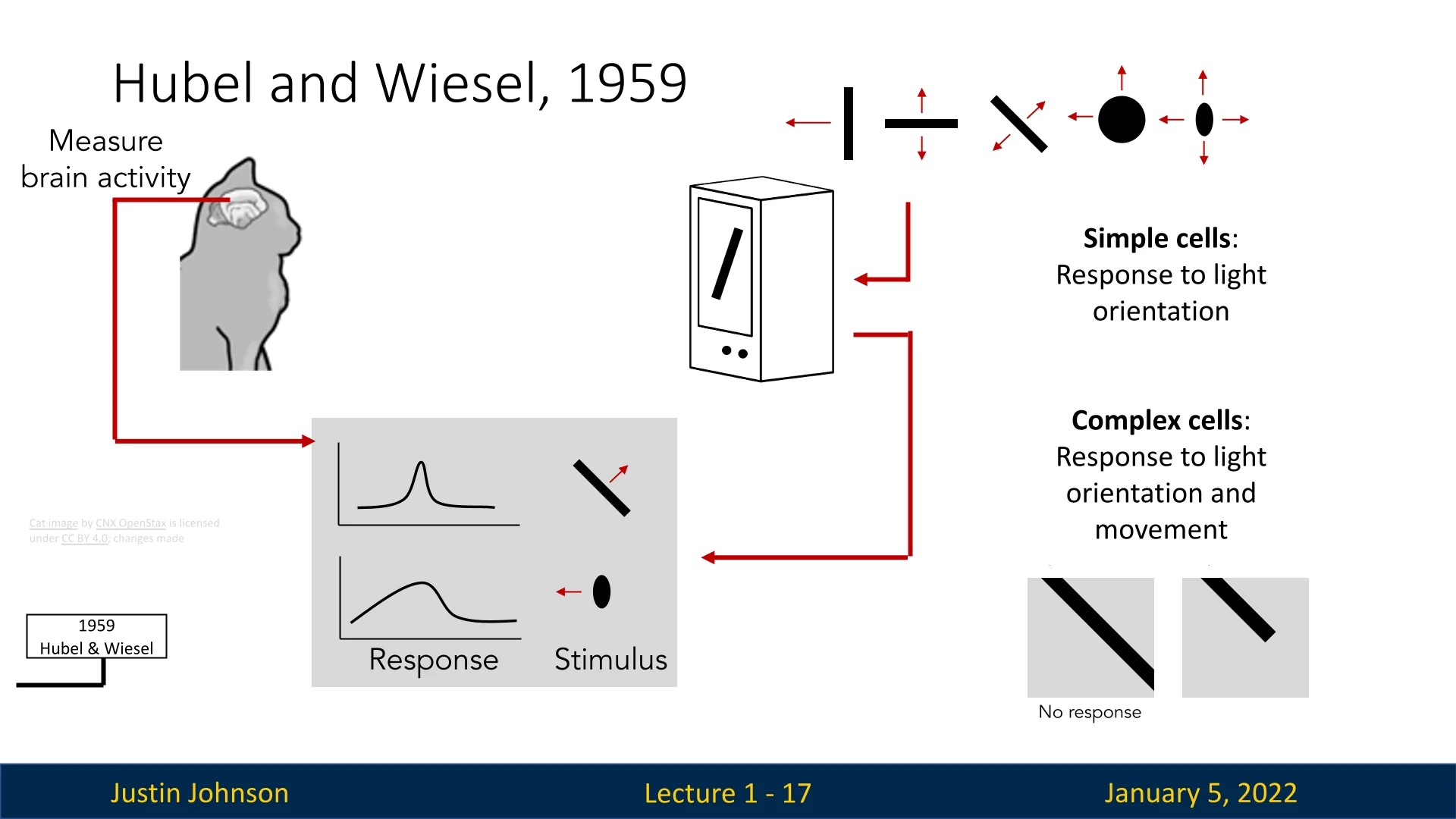

1.3.1 Hubel and Wiesel (1959): How Vision Works?

Hubel and Wiesel’s pioneering work in the late 1950s explored the visual cortex of cats using electrodes, uncovering two critical insights. First, they identified specialized neurons that respond to specific visual stimuli, such as edges with particular orientations. Second, they revealed a hierarchical structure in visual processing, where simple features combine to form complex patterns. These discoveries laid the foundation for artificial neural networks and convolutional architectures, which are integral to modern computer vision [249].

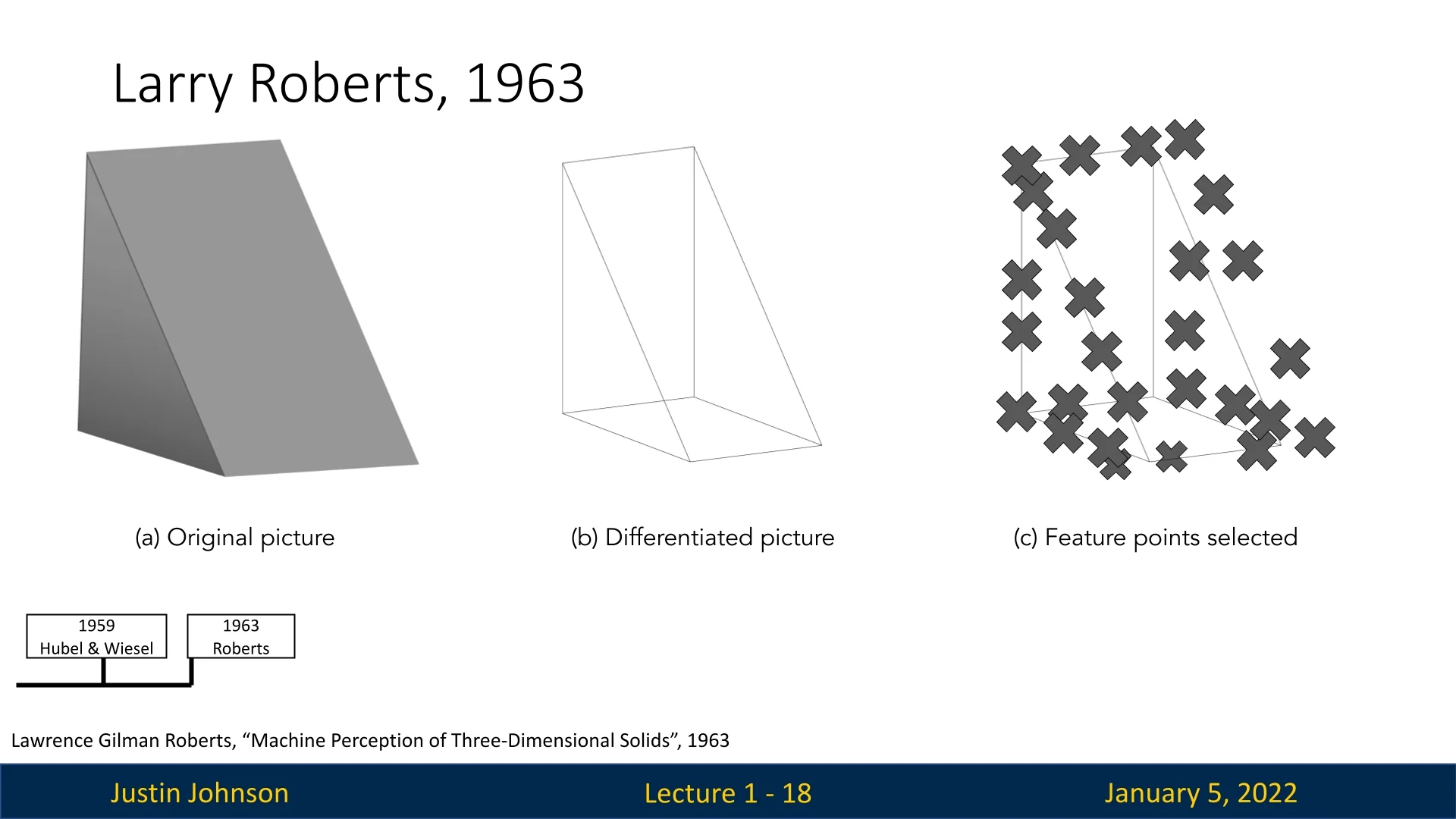

1.3.2 Larry Roberts (1963): From Edges to Keypoints

Larry Roberts’ groundbreaking PhD thesis in 1963 is often regarded as one of the earliest foundational works in computer vision. Inspired by the findings of Hubel and Wiesel on visual processing, Roberts focused on extracting edges from images, proposing methods to detect keypoints like corners. His work went beyond edge detection, leveraging these features to analyze the 3D geometry of objects in images, thus laying the groundwork for object recognition and scene understanding [529].

1.3.3 David Marr (1970s): From Features to a 3D Model

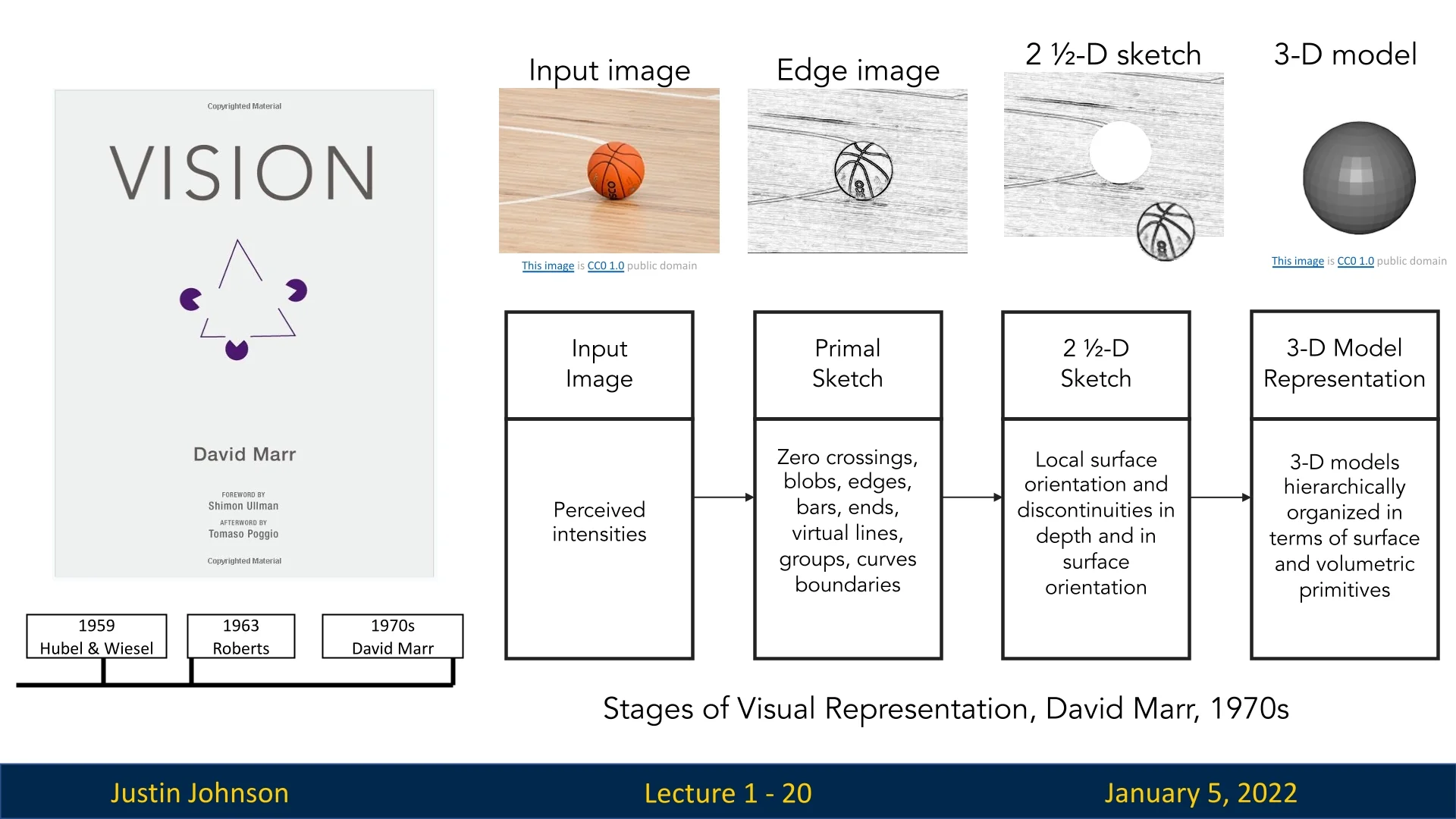

David Marr revolutionized computer vision in the 1970s by introducing a theoretical framework for understanding visual processing, which remains influential to this day. His theory, detailed in his book ’VISION’, proposed that human and artificial vision involve hierarchical, multi-stage processing to extract meaningful information from visual data. Marr’s framework consists of three key stages:

- Primal Sketch: Captures basic image features such as edges, textures, and regions of high contrast, forming a simplified representation of the scene.

- 2.5D Sketch: Incorporates depth and surface orientation, providing a viewer-centric representation that bridges raw image data and object geometry.

- 3D Model: Creates a complete, three-dimensional understanding of the scene, enabling recognition and interaction with objects.

These concepts profoundly influenced computer vision by emphasizing structured, incremental processing and inspired algorithms for edge detection, depth estimation, and object modeling. Marr’s work continues to shape the field, bridging biological vision studies and artificial intelligence [417].

1.3.4 Recognition via Parts (1970s)

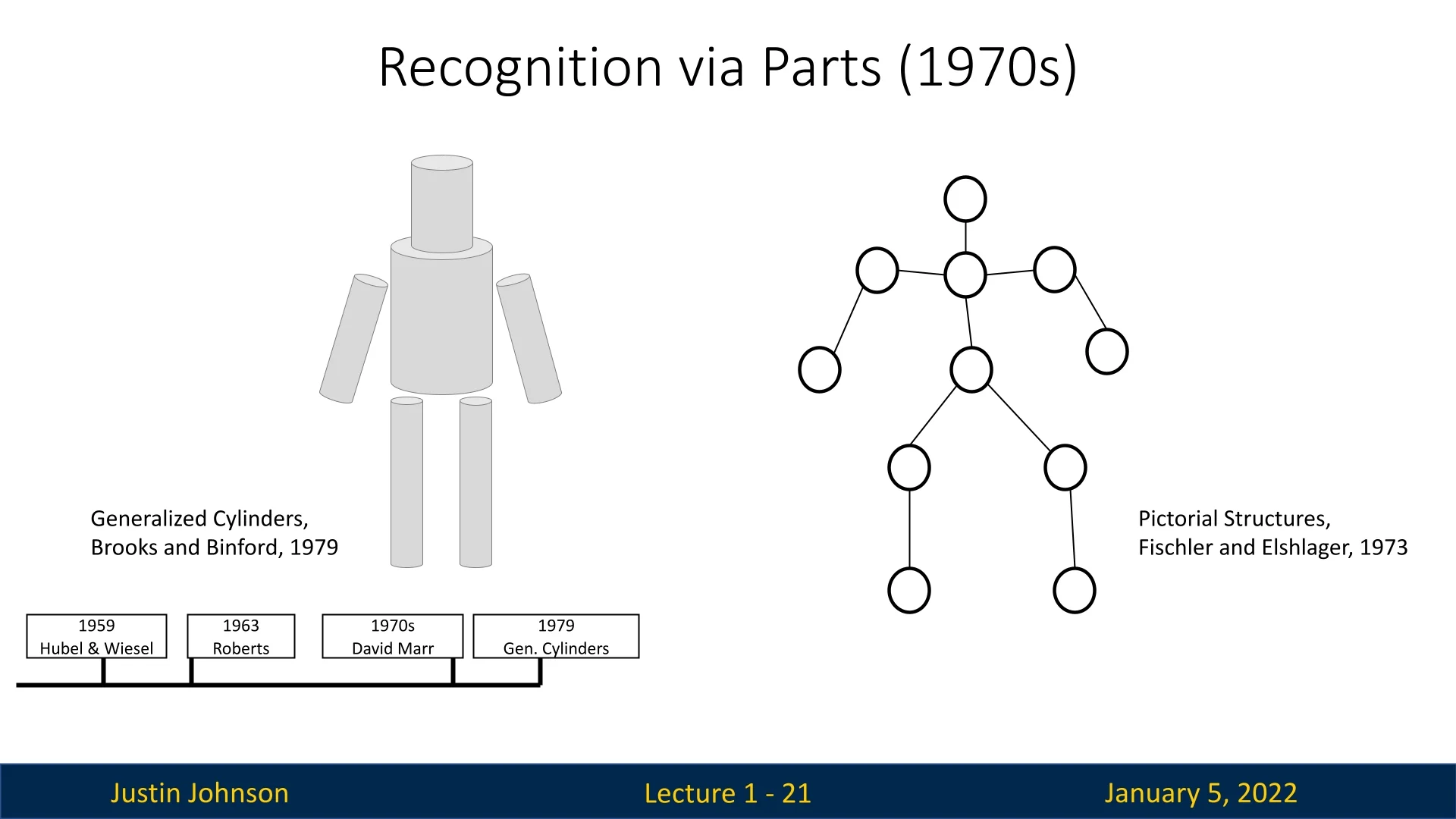

In the 1970s, researchers shifted their focus to recognizing complex objects by building upon earlier advancements in feature extraction. A key breakthrough was the introduction of Generalized Cylinders by Brooks and Binford in 1979 [56], which proposed a model for representing intricate objects using simple geometric shapes. This approach enabled the decomposition of complex structures into manageable components, facilitating object recognition.

Earlier in the decade, Fischler and Elschlager’s Pictorial Structures (1973) introduced a complementary method for object representation. Their approach modeled objects as a collection of interconnected parts with defined spatial relationships, emphasizing the importance of how parts relate to each other in forming a complete object [159]. This method refined the concept of part-based recognition by incorporating spatial constraints, making object recognition systems more robust to variations in appearance.

Both Generalized Cylinders and Pictorial Structures laid the groundwork for part-based models in computer vision, influencing modern techniques such as deformable part models and pose estimation. These foundational ideas continue to impact research in object recognition and scene understanding.

1.3.5 Recognition via Edge Detection (1980s)

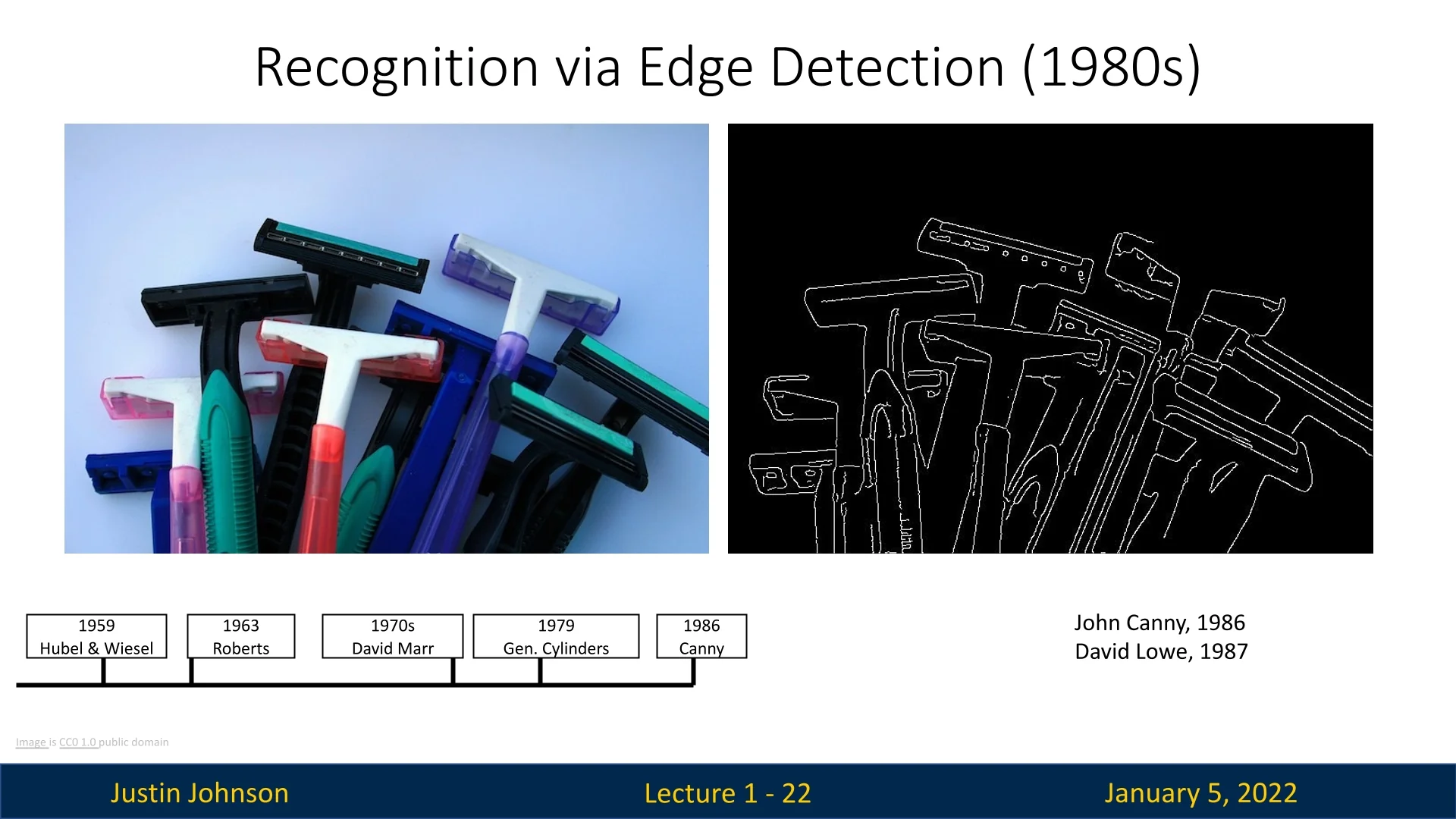

The 1980s marked a pivotal era in computer vision, as advancements in digital cameras and processing hardware enabled researchers to work with more realistic and complex images. A significant focus of this decade was object detection, with edge detection techniques taking center stage.

A landmark contribution was the introduction of the Canny Edge Detector by John Canny in 1986 [63]. This algorithm provided a systematic and efficient method for detecting edges, employing a multi-stage process: noise reduction to enhance clarity, gradient calculation to identify regions of rapid intensity change, non-maximum suppression to thin edges, and edge tracking by hysteresis to ensure continuity. Due to its robustness and accuracy, the Canny edge detector remains a cornerstone in computer vision, widely used in both academic research and industrial applications.

Building upon edge detection, David Lowe’s work in 1987 explored template matching, using edge-based features. Lowe introduced the concept of ”razor templates,” which were derived from reference images to identify similar objects in new images [393]. This approach demonstrated the potential of leveraging edges for object recognition, setting the stage for more sophisticated methods.

However, despite their groundbreaking nature, edge detection and template matching faced limitations. These techniques often struggled with complex, cluttered, or occluded scenes, where edges alone provided insufficient context for robust object detection. For instance, variations in lighting, scale, and viewpoint could significantly degrade the performance of edge-based methods. These challenges highlighted the need for more advanced approaches that could group edges into meaningful structures and match objects more effectively—advancements that would emerge in subsequent decades.

The innovations of the 1980s laid the groundwork for modern object detection, influencing the development of algorithms that continue to shape computer vision systems today.

1.3.6 Recognition via Grouping (1990s)

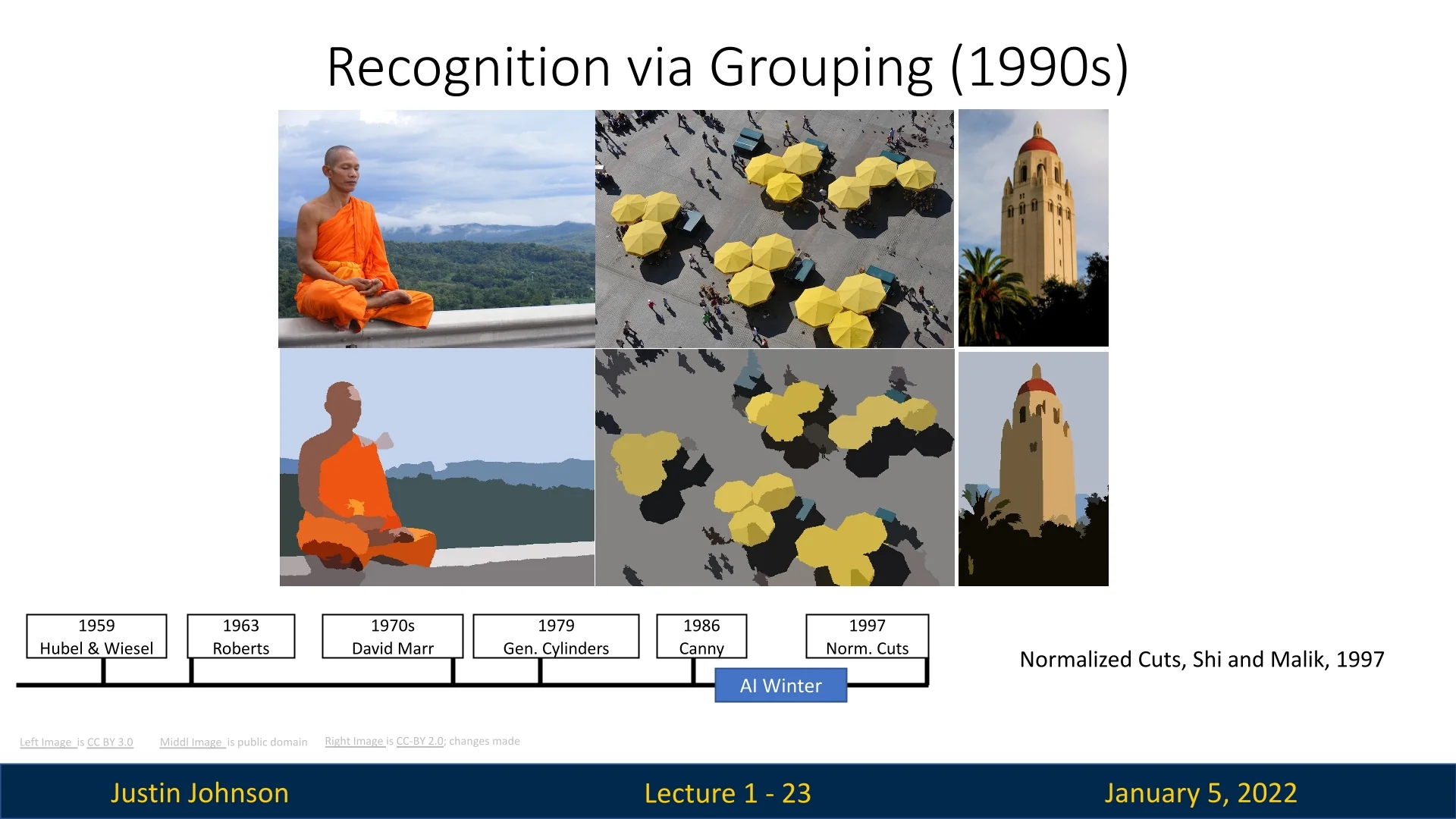

The 1990s saw significant progress in addressing the challenges of recognizing objects in increasingly complex images and scenes. Researchers shifted their focus towards grouping techniques to partition images into meaningful regions, enabling more effective object recognition and scene understanding.

A landmark contribution from this period was the introduction of Normalized Cuts and Image Segmentation by Shi and Malik in 1997 [563]. This method formulated image segmentation as a graph partitioning problem. In their approach, an image is represented as a graph, where pixels or groups of pixels form the nodes, and the edges represent the similarity between these nodes based on features such as color, texture, and spatial proximity.

The primary objective of normalized cuts was to partition the graph into disjoint regions such that: - The similarity within each region (intra-region similarity) is maximized. - The dissimilarity between different regions (inter-region dissimilarity) is minimized.

This framework provided a mathematically rigorous approach to image segmentation, allowing for the grouping of image regions that are internally cohesive while being distinct from other regions. Compared to earlier heuristic-based methods, normalized cuts offered a more unified and generalizable solution, capable of handling a wide range of segmentation tasks.

Shi and Malik’s method was particularly impactful as it addressed the need for global optimization in segmentation, rather than relying solely on local features. It paved the way for further advancements in scene analysis, object recognition, and video segmentation. The ability to group and label regions effectively has since become a foundational concept in computer vision, influencing modern techniques such as region proposal networks used in deep learning-based object detection.

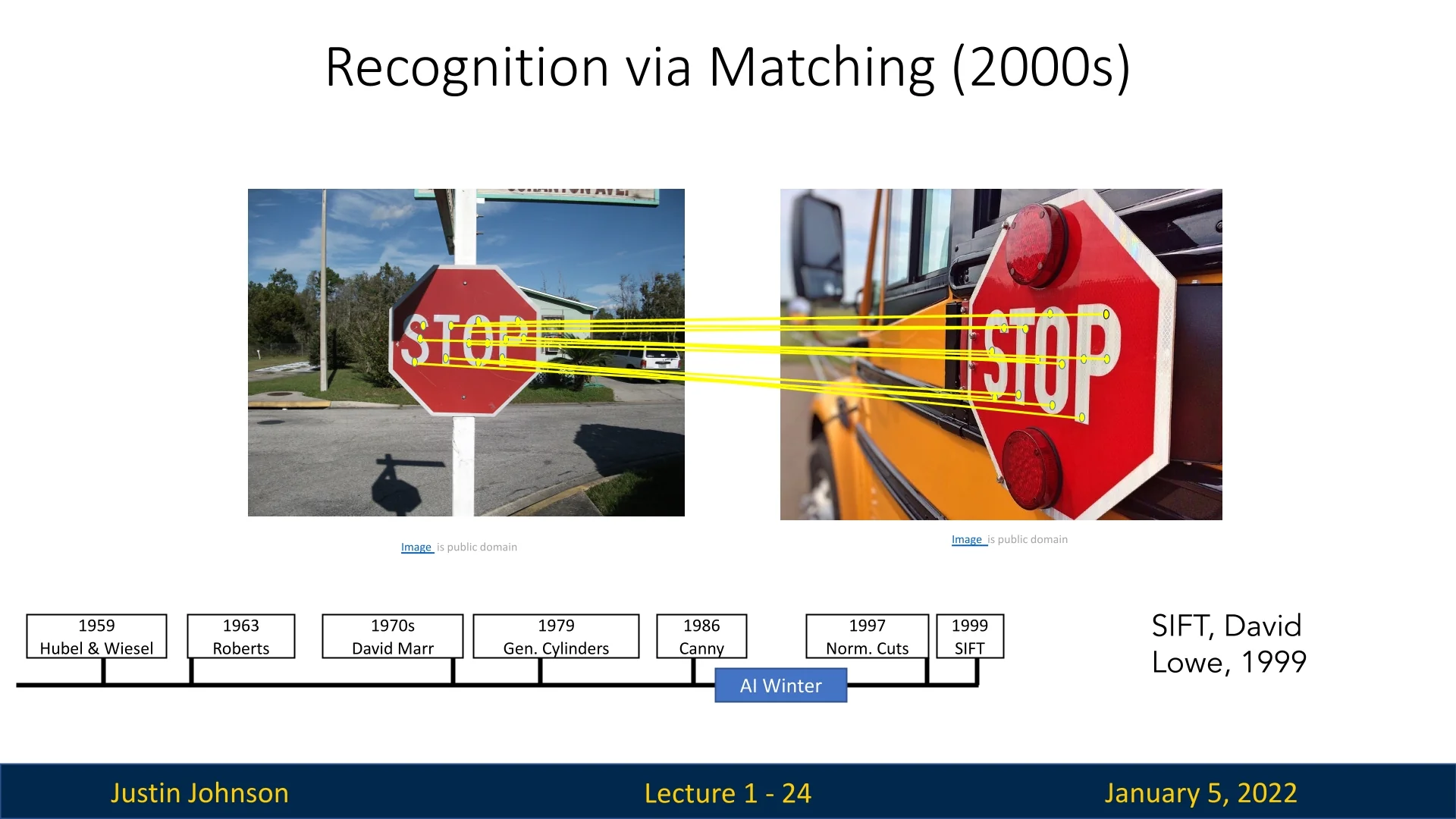

1.3.7 Recognition via Matching and Benchmarking (2000s)

The 2000s marked a transformative period in computer vision, characterized by advancements in feature matching and the establishment of benchmarks that fueled innovation.

One of the era’s most influential algorithms was the Scale-Invariant Feature Transform (SIFT), introduced by David Lowe in 1999 [394]. SIFT provided a robust framework for detecting and describing keypoints in images, enabling reliable matching across variations in scale, rotation, and lighting. The algorithm comprises three key steps:

- Keypoint Detection: Identifies potential keypoints by detecting extrema in a Difference of Gaussian (DoG) function applied across multiple scales.

- Keypoint Description: Creates a feature vector based on the local gradient orientations around each keypoint.

- Keypoint Matching: Compares descriptors between images to establish correspondences, facilitating tasks like object recognition and image stitching.

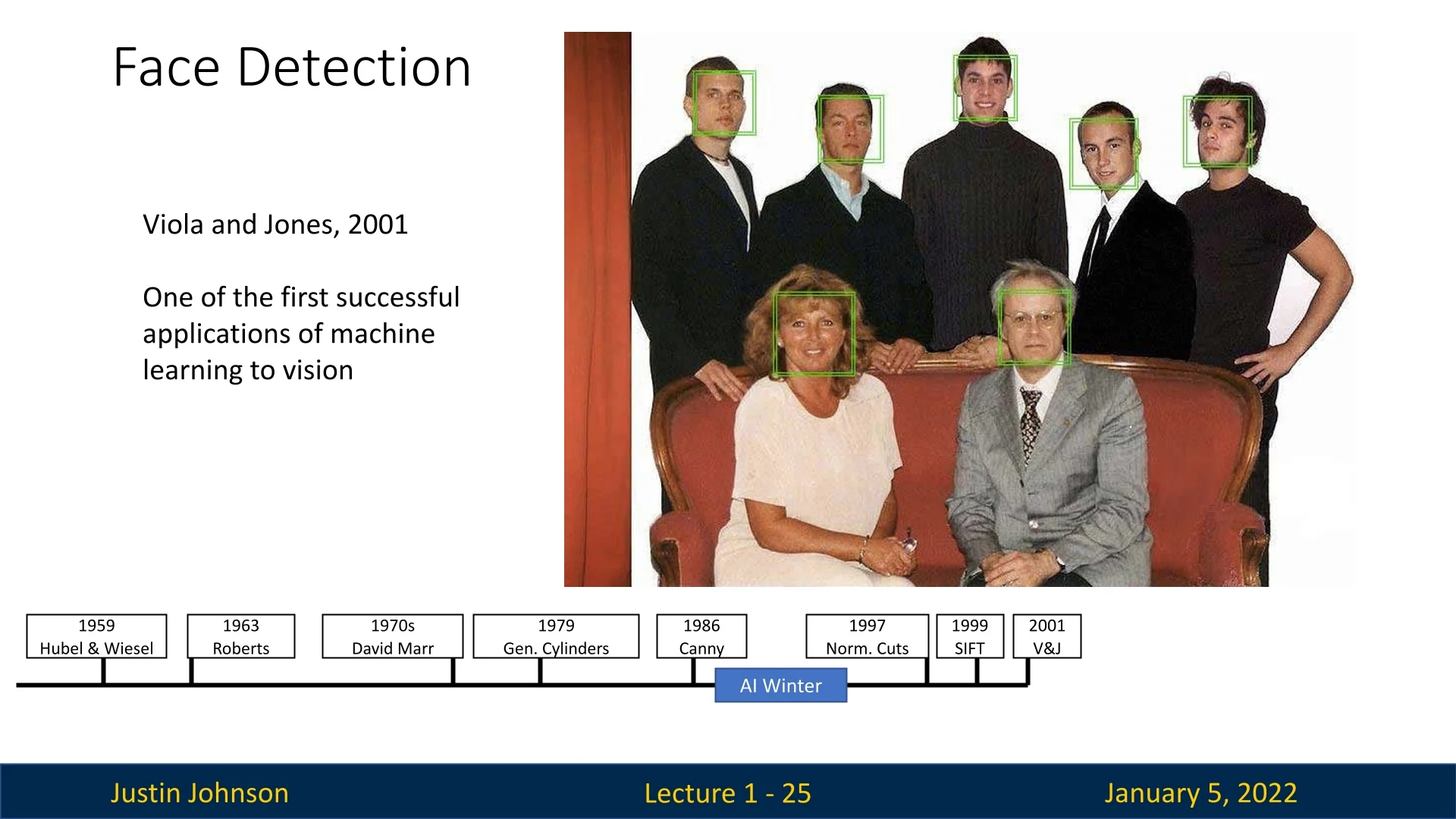

Another groundbreaking development from this period was the Viola-Jones Face Detection Algorithm, introduced in 2001 [649]. This method employed boosted decision trees for real-time face detection, laying the groundwork for machine learning applications in computer vision. The algorithm’s efficiency and robustness made facial recognition a ubiquitous feature in consumer electronics, such as digital cameras and smartphones.

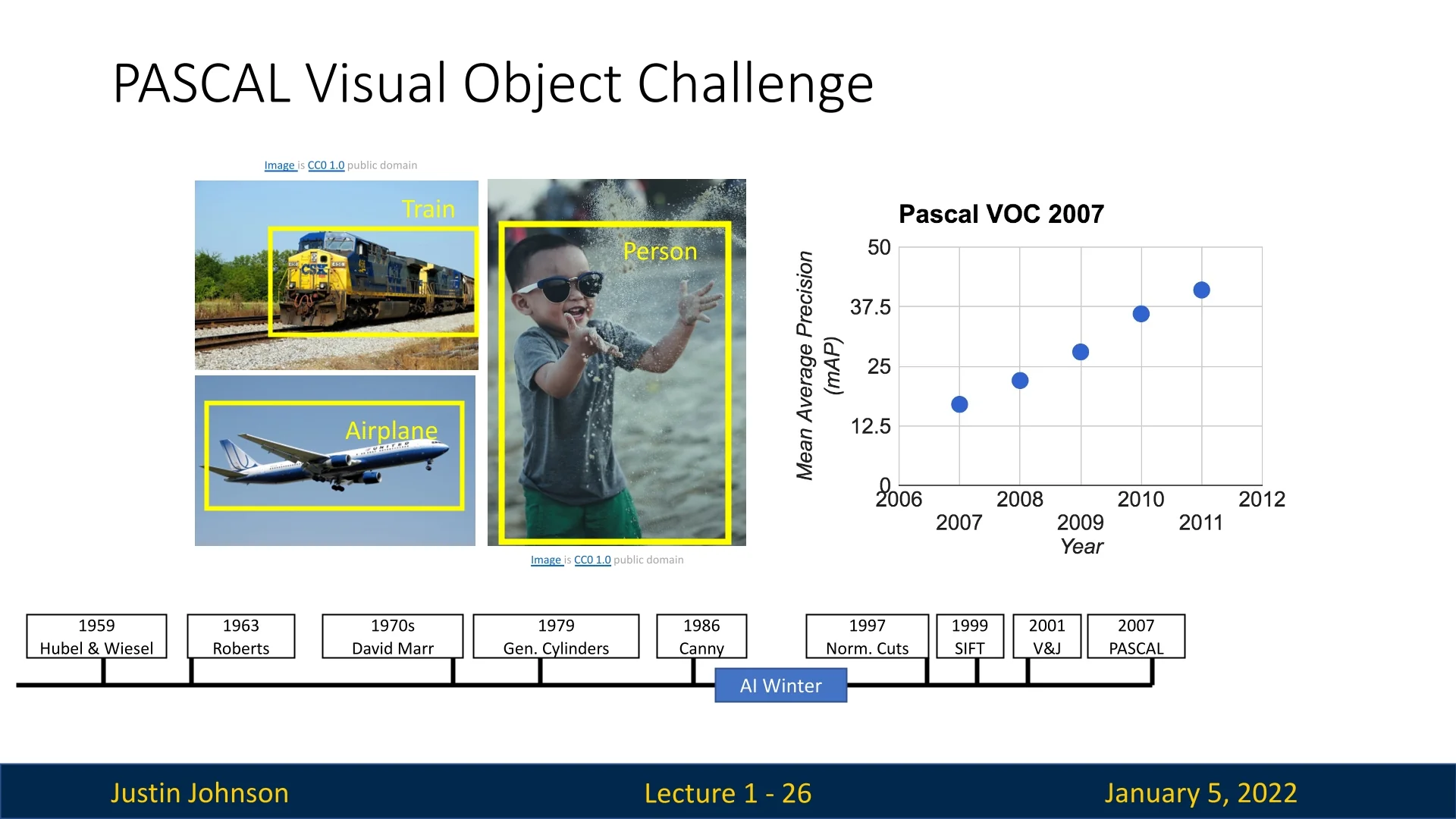

The establishment of benchmarks during this period significantly advanced computer vision research. The PASCAL Visual Object Challenge, introduced in 2005, provided a competitive platform to evaluate object detection and recognition algorithms across various categories [150]. It encouraged collaboration and set a new standard for algorithmic performance, inspiring innovations that continue to shape the field today.

1.3.8 The ImageNet Dataset and Classification Challenge

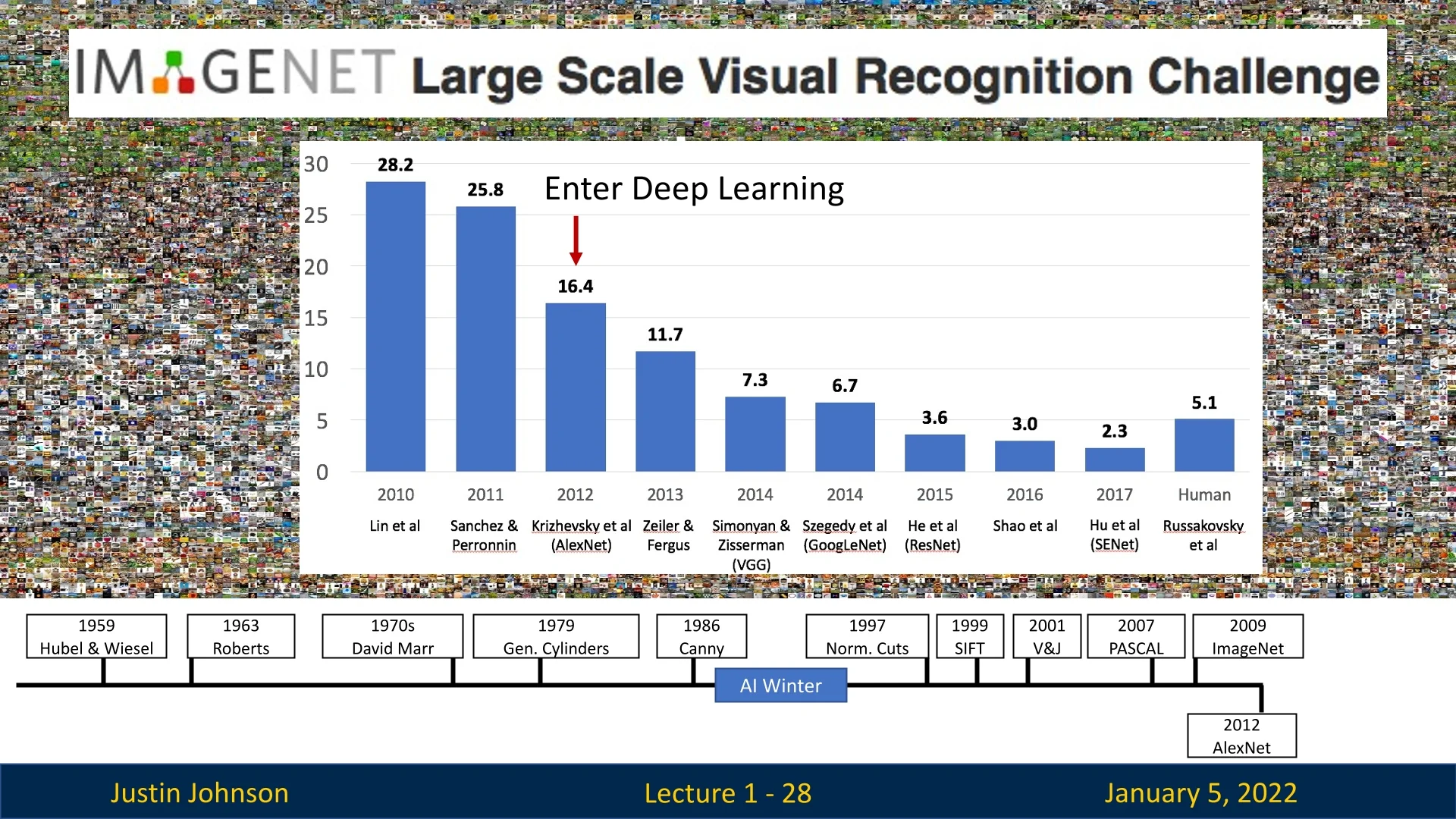

The introduction of the ImageNet dataset in 2009 marked a new era in computer vision [118]. This large-scale dataset contains over 1.4 million labeled images across 1,000 object categories, providing a rich resource for training and evaluating visual recognition systems. The annual ImageNet Large Scale Visual Recognition Challenge (ILSVRC) became a benchmark competition, driving significant advances in image classification and object detection. Key milestones include:

- 2010-2011: Traditional feature-based methods achieved error rates of around 28-25%.

- 2012: The introduction of AlexNet, a deep convolutional neural network, reduced the error rate to 16%, initiating the deep learning revolution [307].

- 2015: The advent of deeper architectures, such as ResNet, achieved near-human performance with error rates below 5%.

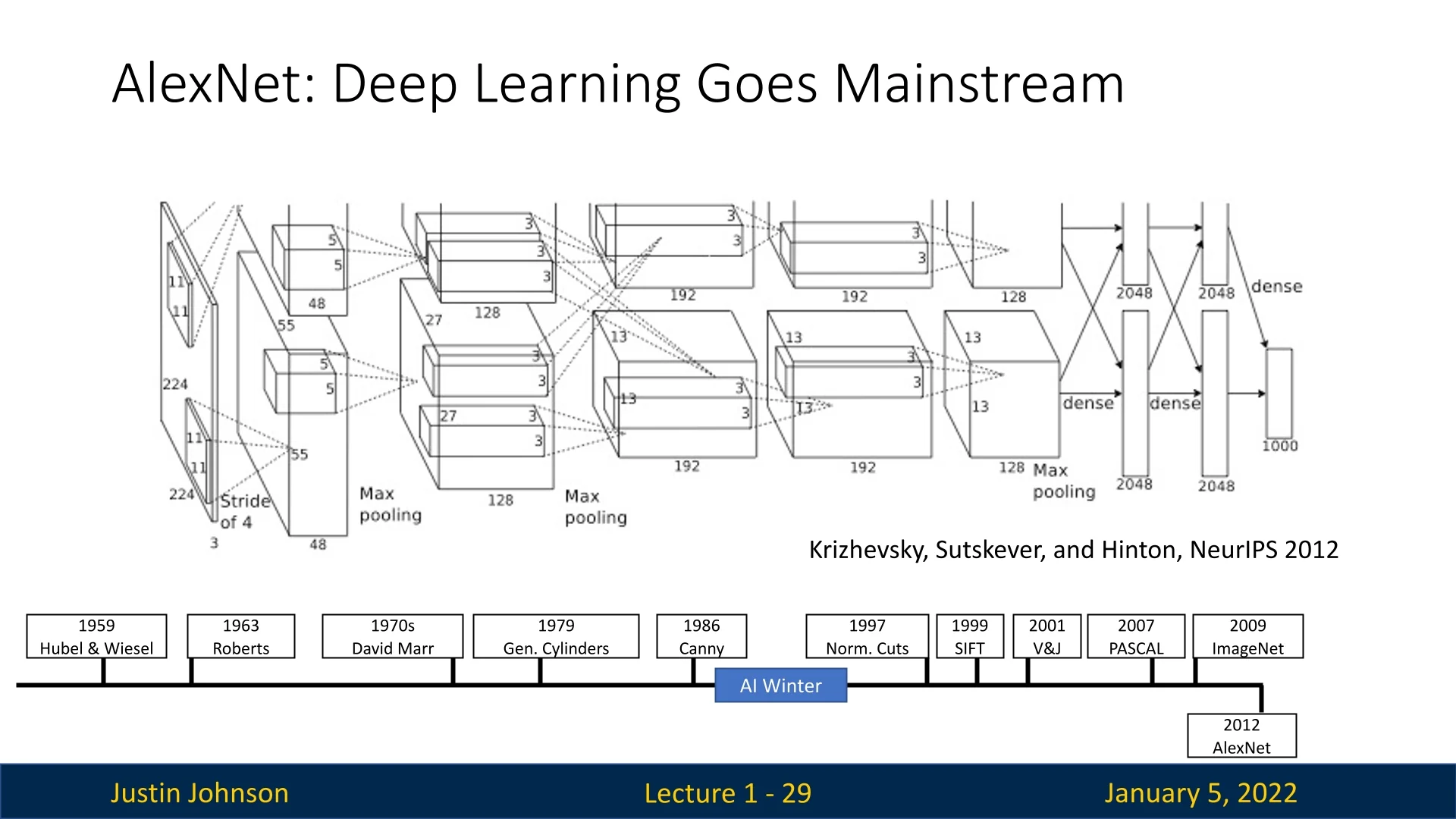

1.3.9 AlexNet: A Revolution in Computer Vision (2012)

The success of AlexNet in the 2012 ImageNet Large Scale Visual Recognition Challenge (ILSVRC) was a turning point in computer vision. Developed by Alex Krizhevsky, Ilya Sutskever, and Geoffrey Hinton, AlexNet achieved a top-5 error rate of 16%, significantly outperforming the runner-up at 26% [307]. This achievement demonstrated the practical power of deep learning, establishing convolutional neural networks (CNNs) as the dominant paradigm for computer vision.

Key innovations in AlexNet included:

- GPU Acceleration: AlexNet utilized NVIDIA GTX 580 GPUs for parallelized training, making large-scale deep learning computationally feasible for the first time.

- Rectified Linear Units (ReLU): By addressing the vanishing gradient problem, ReLU activation functions allowed for faster convergence and deeper architectures.

- Dropout Regularization: This technique reduced overfitting by randomly deactivating neurons during training, improving model generalization.

- Data Augmentation: Methods such as random cropping and flipping artificially expanded the training dataset, mitigating overfitting and enhancing robustness.

- Deep Architecture: AlexNet’s eight-layer design enabled hierarchical feature extraction, capturing increasingly abstract patterns in visual data.

AlexNet’s success not only popularized GPUs for training but also showcased the potential of deep learning to outperform traditional methods on complex visual tasks. It set the stage for a wave of transformative innovations in the years that followed.

Building on AlexNet: Evolution of CNNs and Beyond

The success of AlexNet in 2012 catalyzed a wave of advancements in convolutional neural networks (CNNs), setting the stage for deeper architectures, new paradigms, and transformative innovations in neural network design.

ResNets and Deeper CNN Architectures (2015)

While AlexNet showcased the power of deep CNNs, increasing network depth introduced the vanishing gradient problem, where gradients diminish as they propagate backward through the network, impeding effective training. This challenge was addressed by Residual Networks (ResNets), proposed by He et al. in 2015 [206], which introduced skip connections (or residual connections). These connections allowed gradients to bypass certain layers, ensuring stable training even in networks with hundreds or thousands of layers.

ResNets demonstrated that very deep networks could achieve superior performance without overfitting, achieving state-of-the-art results in tasks like image classification and object detection. The success of ResNets established deep residual learning as a cornerstone of modern deep learning.

Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) and LSTMs

RNNs emerged as a natural choice for sequential data processing due to their ability to maintain a hidden state that evolves over time. Although introduced in the 1980s [538], their application to computer vision became prominent in the 2010s, especially for video analysis, activity recognition, and image captioning.

However, standard RNNs struggled with long-term dependencies due to the vanishing gradient problem. This limitation was overcome by Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks, introduced by Hochreiter and Schmidhuber in the 1990s [227]. LSTMs employ gating mechanisms to selectively retain, forget, and pass on information, enabling robust modeling of long-range temporal dependencies. Despite their success in tasks like video captioning and temporal activity recognition [131], LSTMs have key drawbacks:

- Sequential Nature: LSTMs process data sequentially, limiting parallelization and increasing computational expense.

- Scalability Challenges: As sequence lengths grow, LSTMs often struggle to generalize and capture global context.

These limitations paved the way for the development of attention mechanisms, which revolutionized the handling of sequential data.

Vision Transformers (ViTs) and Attention Mechanisms

The attention mechanism, popularized by Vaswani et al.’s seminal work ”Attention Is All You Need” in 2017 [644], fundamentally changed how neural networks process data. Attention allows models to dynamically focus on relevant parts of the input data while ignoring irrelevant information. In the context of sequences, attention computes the relationship (or relevance) between tokens, assigning higher weights to important elements.

Self-attention, a specific form of attention, operates within a single sequence by relating each token to every other token. It uses three key components:

- Queries (Q): Represent the current token of interest.

- Keys (K) and Values (V): Represent other tokens in the sequence.

The relevance of a token is computed as a scaled dot product between queries and keys, weighted by the corresponding values.

Transformers, models built on the concept of self-attention, initially designed for natural language processing, were extended to computer vision tasks with the introduction of Vision Transformers (ViTs) [133]. ViTs divide an image into patches, treating each patch as a token in a sequence. Self-attention mechanisms are then used to capture global dependencies across the image.

ViTs demonstrated state-of-the-art performance in image classification, object detection, and segmentation, overcoming limitations of CNNs:

- Global Context: Self-attention enables the model to capture long-range dependencies efficiently.

- Scalability: Transformers are highly parallelizable, making them suitable for large-scale datasets and models.

However, Transformers have their own limitations:

- Memory Intensity: Self-attention scales quadratically with the sequence length, making it computationally expensive for high-resolution images.

- Data Dependency: Transformers often require massive datasets to generalize effectively, unlike CNNs that perform well with smaller datasets.

MAMBA: Linear-Time Sequence Modeling with Selective State Spaces (2022)

MAMBA [190] introduces a new paradigm in sequence modeling by leveraging structured state space models (SSMs) for efficient long-range dependency learning. Unlike traditional self-attention, MAMBA achieves linear-time complexity, making it a scalable alternative for high-dimensional sequential data. This approach improves computational efficiency while retaining the ability to capture complex dependencies, making it particularly useful for vision-based sequence modeling and multimodal learning.

Foundation Models: From Vision to Multimodal Intelligence

The progression from AlexNet has led to the rise of foundation models, which integrate vision, language, and multimodal capabilities. Notable examples include:

- DINO (2021): Self-supervised learning using Vision Transformers to learn robust representations without labels [71].

- CLIP (2021): Aligning vision and language embeddings for cross-modal understanding and zero-shot classification [497].

- Segment Anything Model (SAM) (2023): Generalizing image segmentation across diverse datasets [296].

- Flamingo (2022): Visual language models combining vision and language reasoning for tasks like visual question answering [6].

Conclusion

The legacy of AlexNet extends far beyond its initial success, shaping the evolution of neural network architectures and driving breakthroughs in computer vision. From CNNs to attention-based models like ViTs, and from vision-specific tasks to multimodal intelligence, this journey reflects the field’s relentless pursuit of scalable, adaptable, and powerful algorithms.

1.4 Milestones in the Evolution of Learning in Computer Vision

The evolution of learning-based approaches in computer vision has been marked by pivotal milestones, each building upon its predecessors to push the boundaries of what artificial systems can achieve. From the early perceptron to the transformative AlexNet, these developments highlight the progression of ideas and innovations that laid the groundwork for modern deep learning.

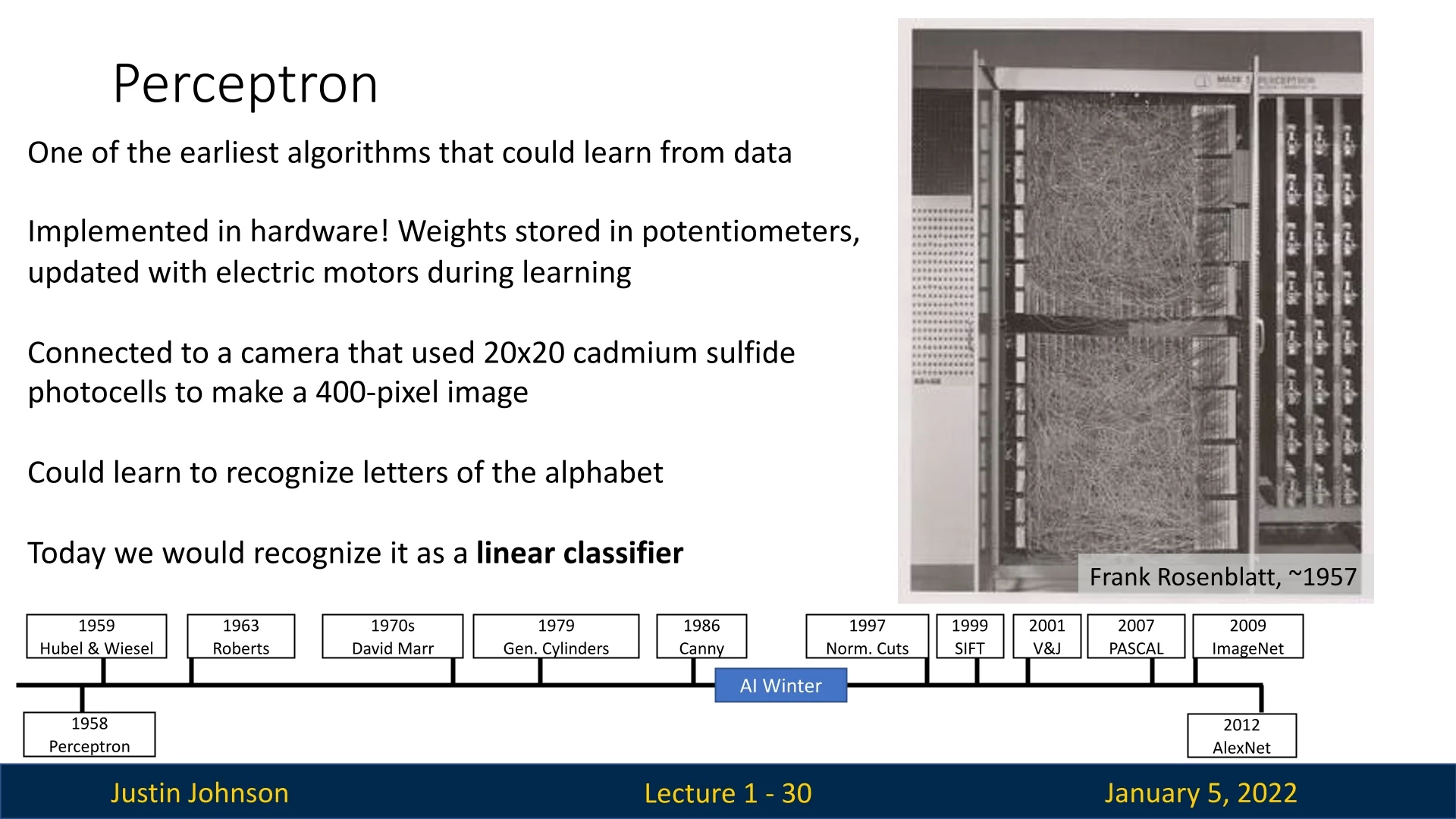

1.4.1 The Perceptron (1958)

The Perceptron, introduced by Frank Rosenblatt in 1958, was the first neural network capable of learning from data. Designed as a single-layer classifier, it demonstrated that machines could adjust their weights iteratively based on error corrections, enabling them to classify data using linear boundaries.

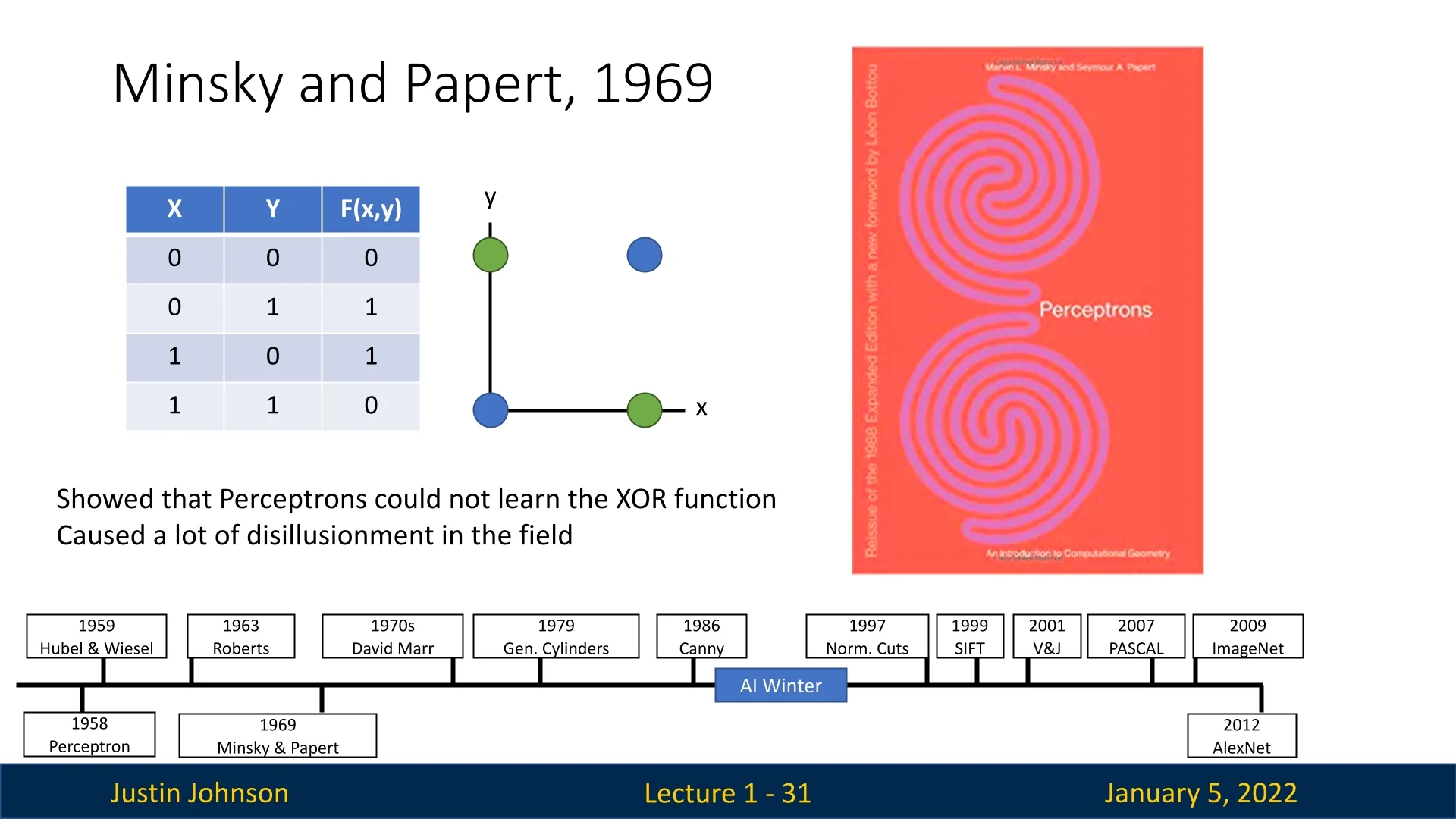

Despite its early promise, the perceptron had significant limitations, particularly its inability to solve non-linear problems such as XOR. These shortcomings were later critiqued in the influential book ”Perceptrons” by Marvin Minsky and Seymour Papert in 1969, which highlighted the theoretical constraints of single-layer networks [533, 434].

1.4.2 The AI Winter and Multilayer Perceptrons (1969)

Minsky and Papert’s critique, while valid, inadvertently led to an ”AI Winter,” a period of reduced interest and funding in neural network research. However, their work also suggested that multilayer perceptrons could overcome the limitations of single-layer networks by introducing hidden layers. Unfortunately, at the time, efficient training methods for such architectures were unavailable, stalling progress [434].

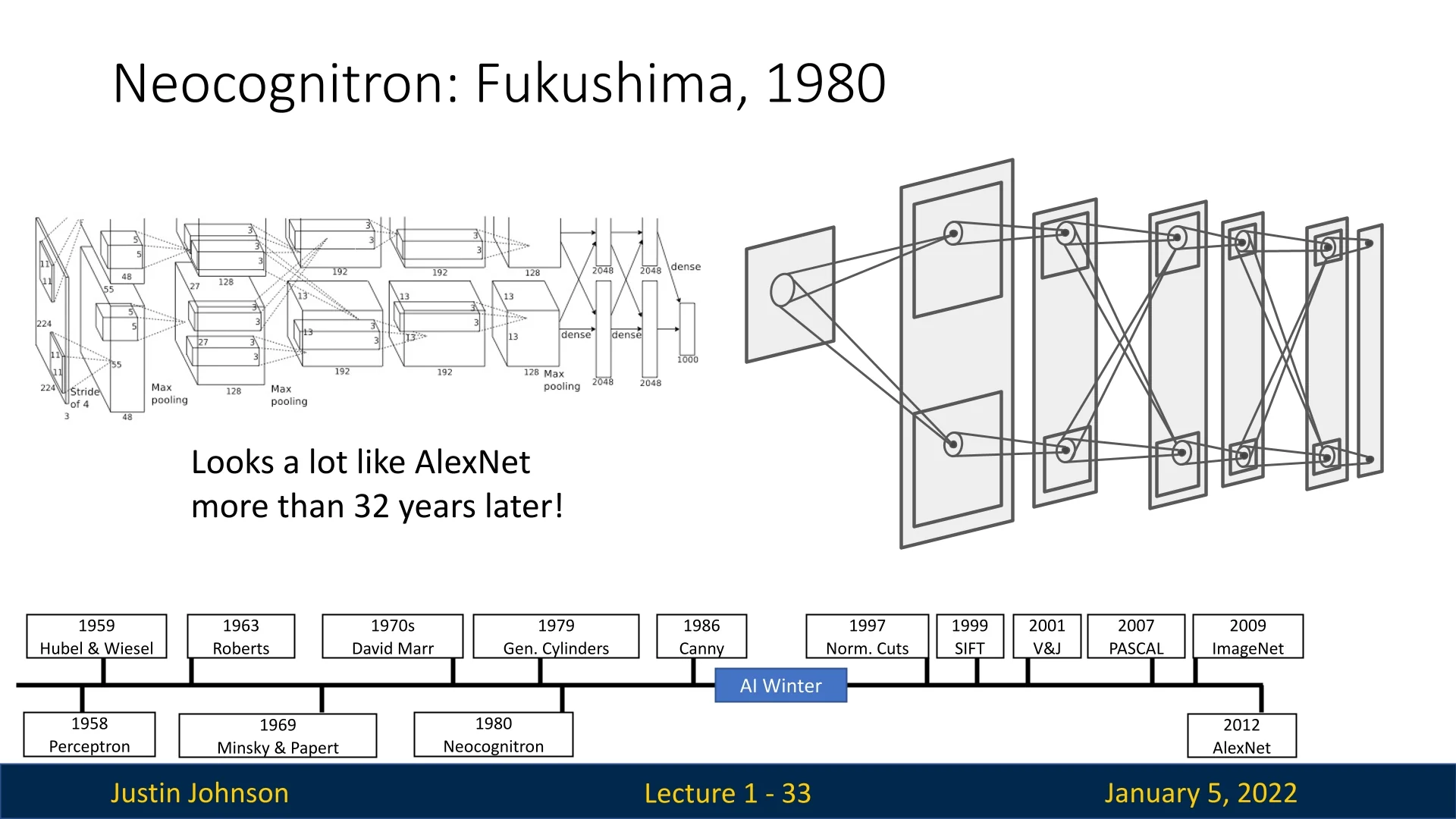

1.4.3 The Neocognitron (1980)

In 1980, Kunihiko Fukushima introduced the Neocognitron, a hierarchical, multi-layered neural network inspired by the mammalian visual cortex. By combining convolution-like and pooling-like operations, the neocognitron could recognize complex patterns and invariances. While it conceptually resembled modern convolutional neural networks (CNNs), it lacked an efficient algorithm to train its multiple layers, limiting its practical utility. Nevertheless, the neocognitron laid the conceptual groundwork for future breakthroughs [163].

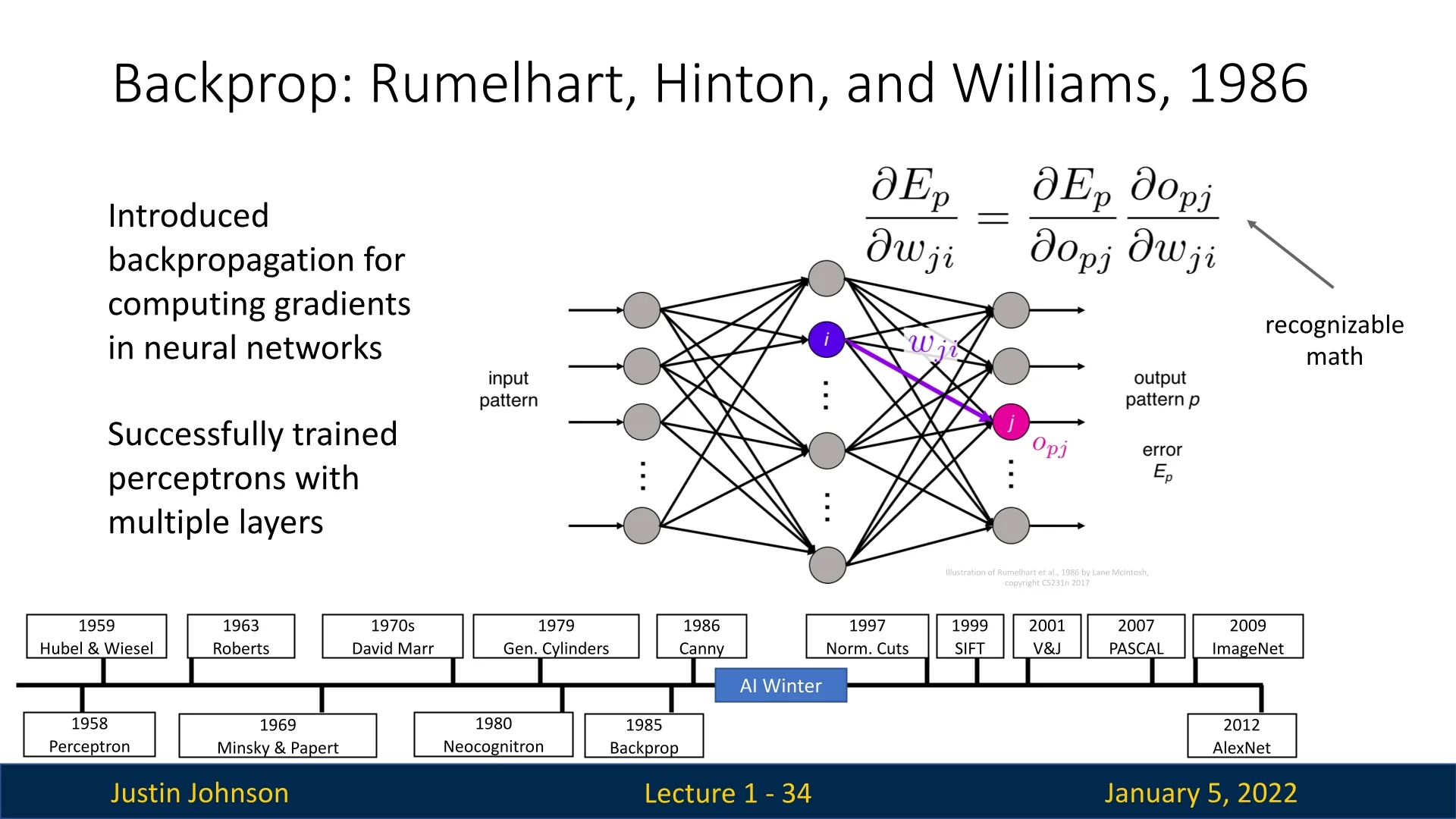

1.4.4 Backpropagation and the Revival of Neural Networks (1986)

The development of Backpropagation in 1986 by Rumelhart, Hinton, and Williams addressed the key limitation of multilayer networks: the lack of an effective training algorithm. By using the chain rule of calculus to compute gradients of the loss function with respect to network weights, backpropagation enabled iterative weight updates via gradient descent. This innovation allowed for the training of deep networks, reigniting interest in neural networks and providing a framework for the architectures that followed [538].

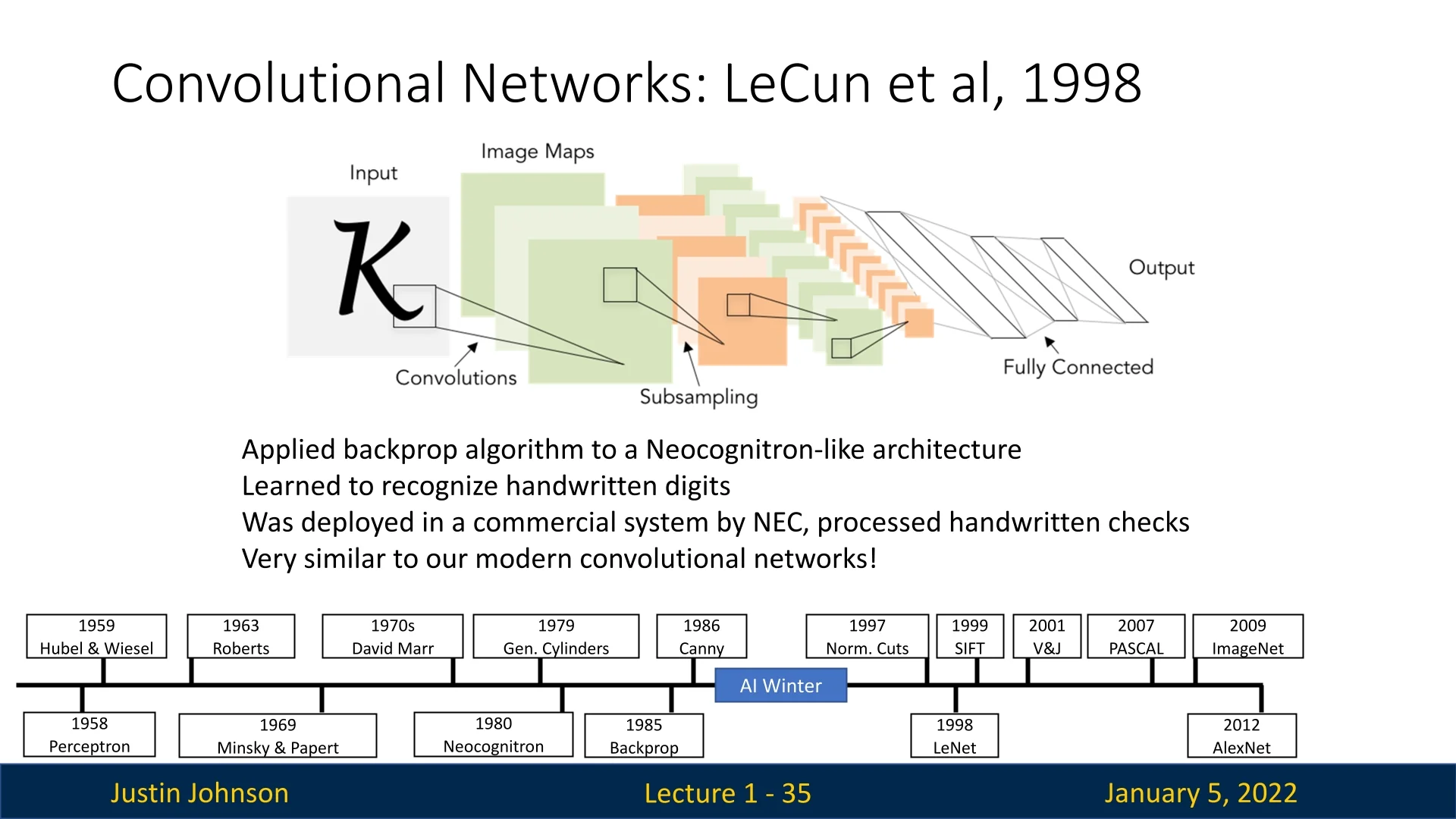

1.4.5 LeNet and the Emergence of Convolutional Networks (1998)

In 1998, Yann LeCun and colleagues introduced LeNet-5, a convolutional neural network (CNN) designed for handwritten digit recognition. By incorporating convolutional layers for feature extraction and pooling layers for dimensionality reduction, LeNet demonstrated the power of hierarchical architectures for pattern recognition. Leveraging backpropagation, it was trained end-to-end, achieving remarkable performance on the MNIST dataset (solving hand-written digits classification) and establishing CNNs as a practical tool for real-world applications [316].

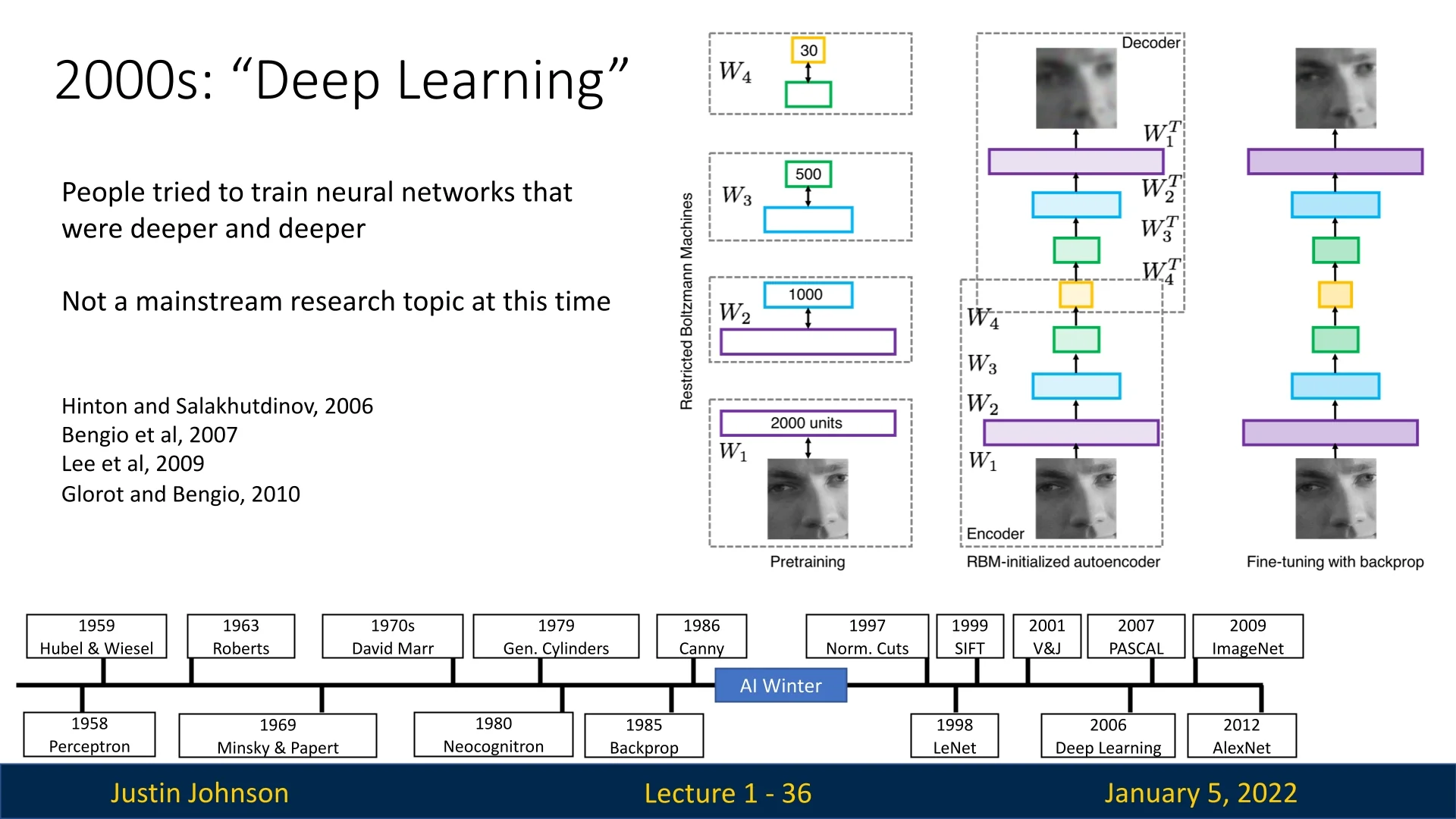

1.4.6 The 2000s: The Era of Deep Learning

The 2000s marked the resurgence of neural networks as Deep Learning emerged as a dominant paradigm. Advances in GPU hardware, large-scale datasets, and improved algorithms made it possible to train deeper networks. Research in convolutional networks, recurrent networks, and self-supervised learning exploded, leading to breakthroughs across various domains.

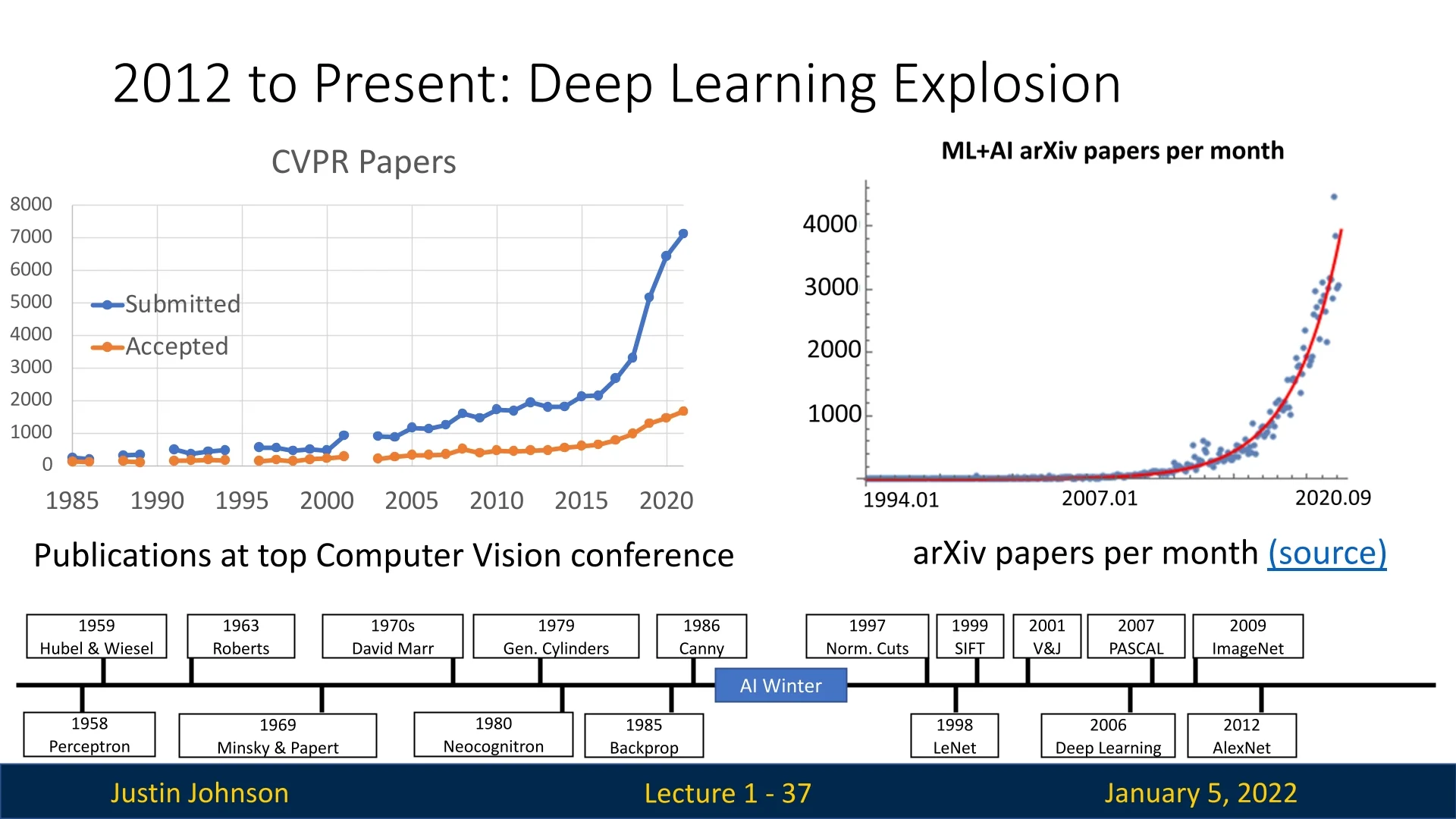

1.4.7 Deep Learning Explosion (2007-2020)

Starting from 2007, the number of deep learning publications grew exponentially, driven by challenges like ImageNet and CVPR competitions. By 2020, deep learning had become ubiquitous, transforming computer vision and establishing itself as a cornerstone of modern AI [118, 307].

1.4.8 2012 to Present: Deep Learning is Everywhere

The transformative success of AlexNet in 2012 heralded the deep learning revolution, marking a paradigm shift across computer vision and artificial intelligence. Since then, deep learning has permeated diverse domains, solving increasingly complex tasks and enabling breakthroughs that were previously unattainable. Below are some of the key tasks and applications transformed by deep learning:

Core Vision Tasks

- Image Classification: Deep learning models like AlexNet [307] and ResNet [206] have achieved state-of-the-art performance on benchmarks like ImageNet.

- Image Retrieval: Features extracted by CNNs are used to search for visually similar images in large datasets, revolutionizing search engines and digital asset management.

- Object Detection: Techniques like Faster R-CNN [522] accurately localize and classify objects in images, enabling applications such as autonomous driving and surveillance.

- Image Segmentation: Models such as DeepLab [82] and Mask R-CNN [209] partition images into semantically meaningful regions, advancing medical imaging and autonomous systems.

Video and Temporal Analysis

- Video Classification: Methods like Two-Stream Networks [571] analyze both spatial and temporal features, enabling tasks like activity recognition.

- Activity Recognition: Deep learning has enabled fine-grained understanding of human activities in videos, aiding applications in healthcare, sports analysis, and surveillance.

- Pose Recognition: Toshev and Szegedy [623] proposed deep architectures for pose estimation, significantly advancing human-computer interaction and animation.

- Reinforcement Learning: In 2014, deep reinforcement learning demonstrated the ability to play Atari games at superhuman levels [706], showcasing the potential of neural networks in sequential decision-making.

Generative and Multimodal Models

- Image Captioning: Vinyals et al. [464] and Karpathy and Fei-Fei [274] introduced models that integrate vision and language, describing images with human-like captions.

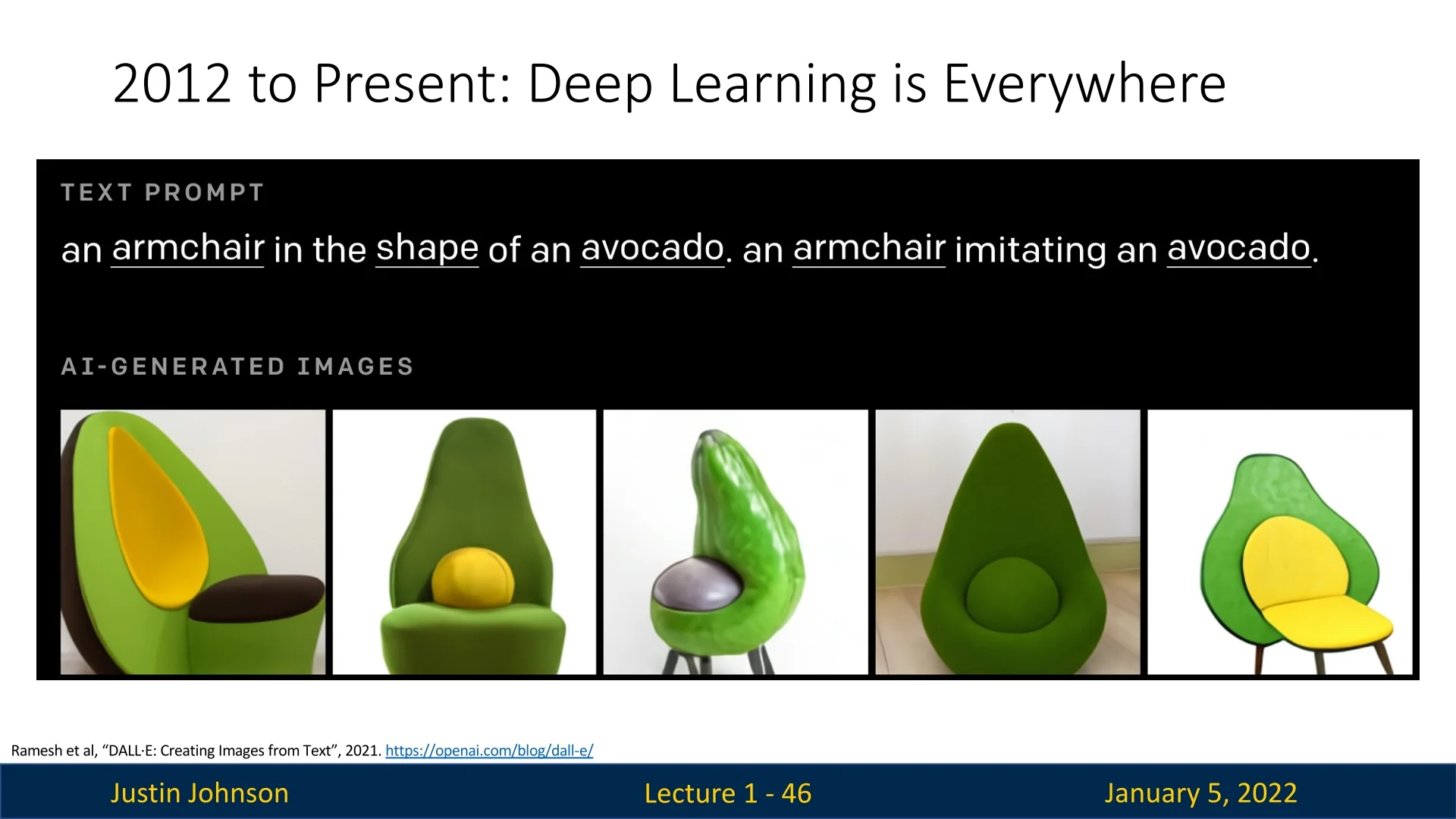

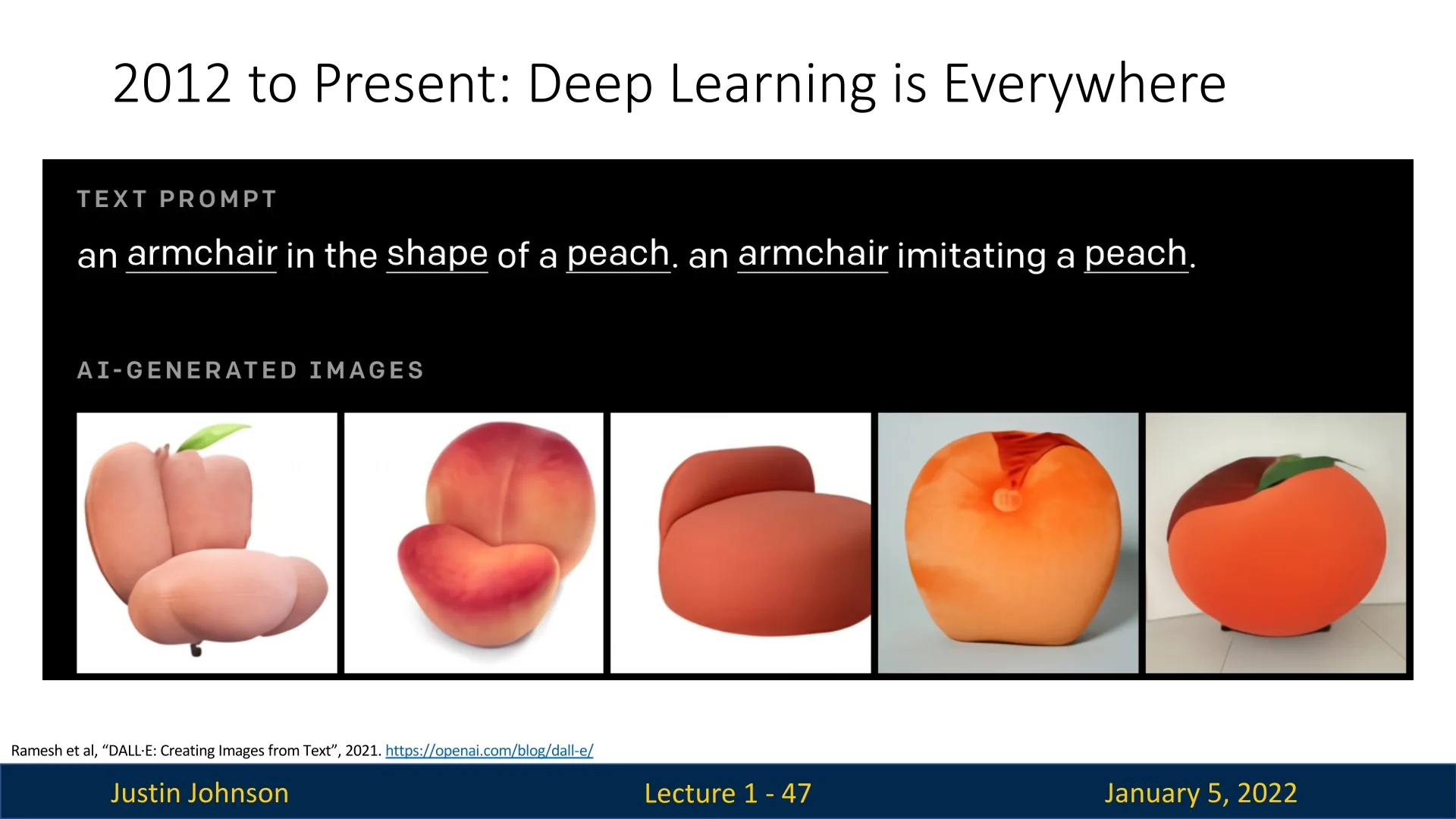

- DALL-E: Recent advancements like DALL-E [507] generate creative visual content, such as the iconic avocado-shaped armchair, pushing the boundaries of generative models.

- Multimodal Models: Foundation models like CLIP [497] and Flamingo [6] align visual and textual embeddings, enabling cross-modal reasoning and applications in content creation and retrieval.

Specialized Domains

- Medical Imaging: Deep learning facilitates disease diagnosis and treatment planning, as seen in Levy et al.’s 2016 work [132].

- Galaxy Classification: Dieleman et al. (2014) [546] used CNNs to classify galaxies, advancing astronomical research.

- Wildlife Recognition: Kaggle challenges like Whale Categorization Playground highlight the role of deep learning in biodiversity studies.

State-of-the-Art Foundation Models

Recent advancements, such as the Segment Anything Model (SAM) [296], DINO [71], and MAMBA [190], exemplify the cutting edge in computer vision. These models were trained on massive amounts of data over extended periods, leveraging vast computational resources to learn robust and generalizable representations.

Their foundational nature lies in their versatility: they can be applied across a wide range of tasks without fine-tuning (or at the very least, minimal fine-tuning), making them highly effective out-of-the-box solutions.

By integrating self-supervised learning, multimodal reasoning, and dynamic scene analysis, these models set new benchmarks in performance and adaptability. Their ability to generalize from diverse and extensive training data makes them a powerful starting point for solving both standard and novel real-world problems.

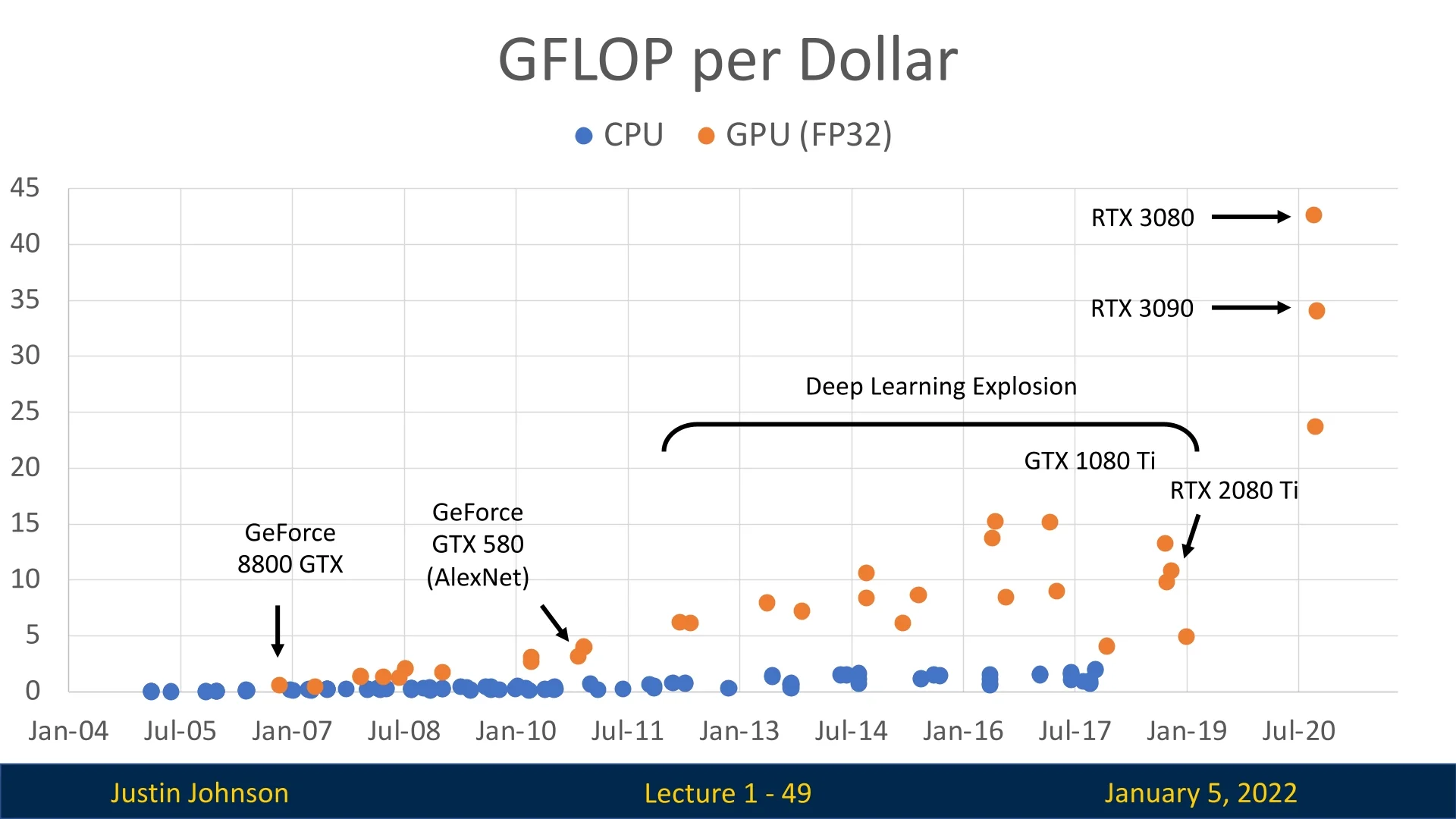

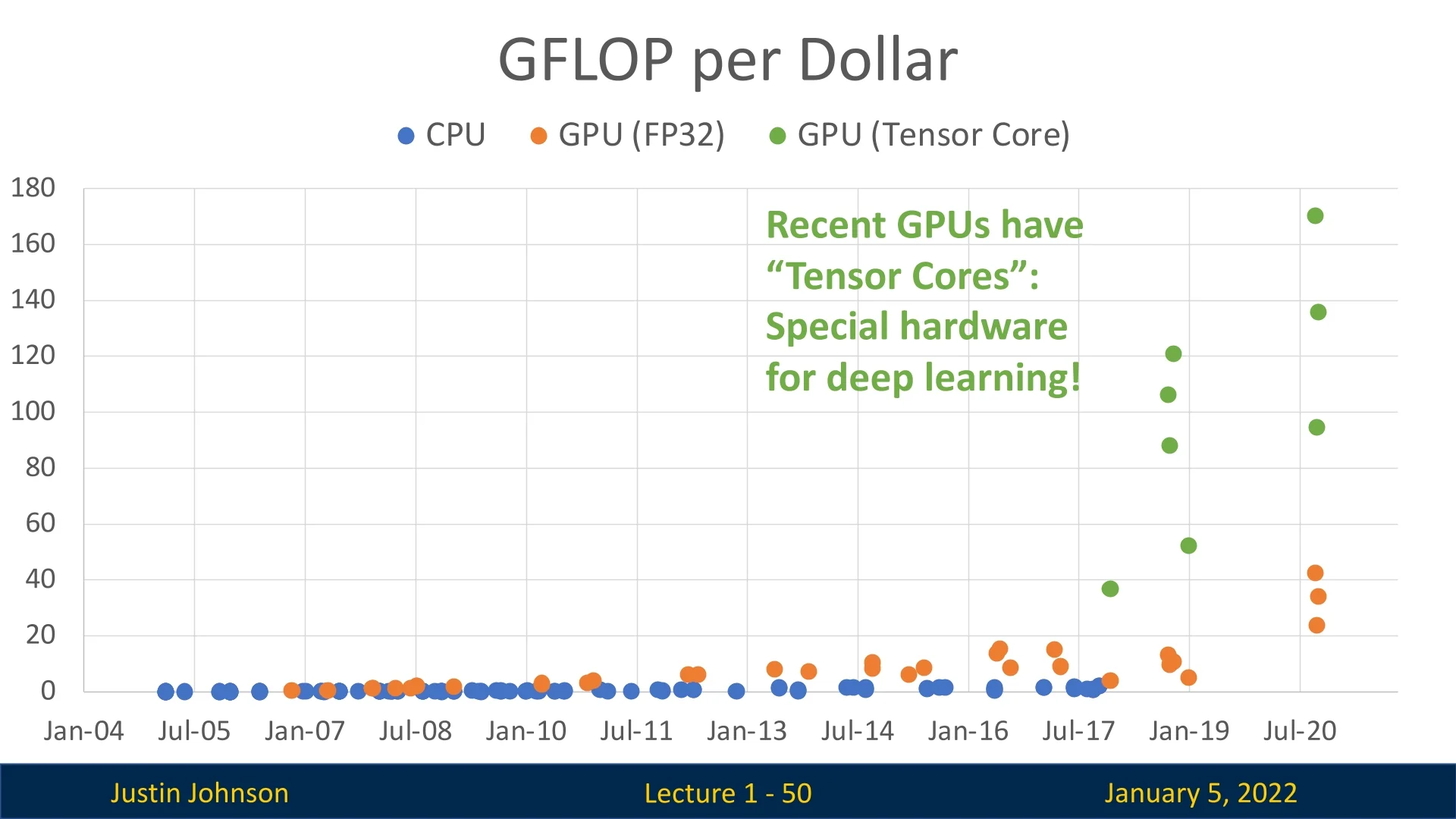

Computation is Cheaper: More GFLOPs per Dollar

The exponential drop in computation costs has driven the deep learning revolution. Over the past decade, GPUs like NVIDIA’s GTX 580 (a pioneering GPU in deep learning, used for training AlexNet) to RTX 3080 have vastly increased performance per dollar. Modern GPUs with tensor cores, optimized for deep learning, deliver unprecedented power for training and inference, enabling breakthroughs in computer vision, NLP, and reinforcement learning. As GFLOPs become increasingly affordable, AI innovation accelerates with fewer resource constraints.

1.5 Key Challenges in CV and Future Directions

Despite remarkable progress, computer vision systems still face significant challenges that underscore their limitations and the need for continued innovation:

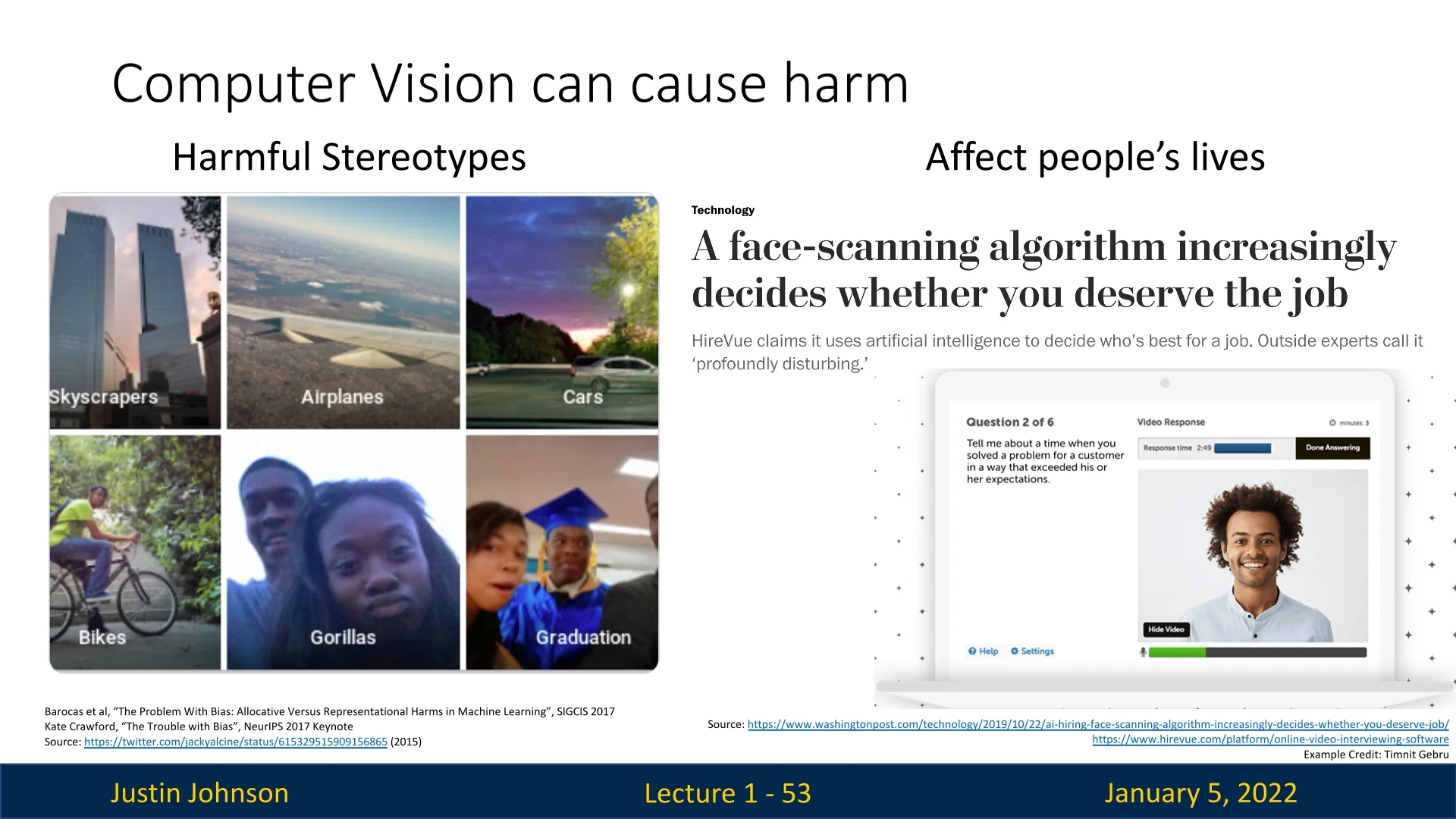

- Model Bias and Ethical Concerns: Bias in training data has led to harmful outcomes, such as facial recognition systems misidentifying Black individuals as apes or employment screening tools unfairly discriminating against candidates. These issues highlight the importance of ethical considerations and fairness in model design and deployment [60].

-

Misapplication Risks: The potential misuse of CV systems poses serious concerns. For example, face-scanning applications might decide a person’s job suitability without understanding context or fairness, raising questions about accountability and societal impact.

Figure 1.25: Ethical concerns: CV systems can amplify biases or cause harm, such as misidentifications [60]. -

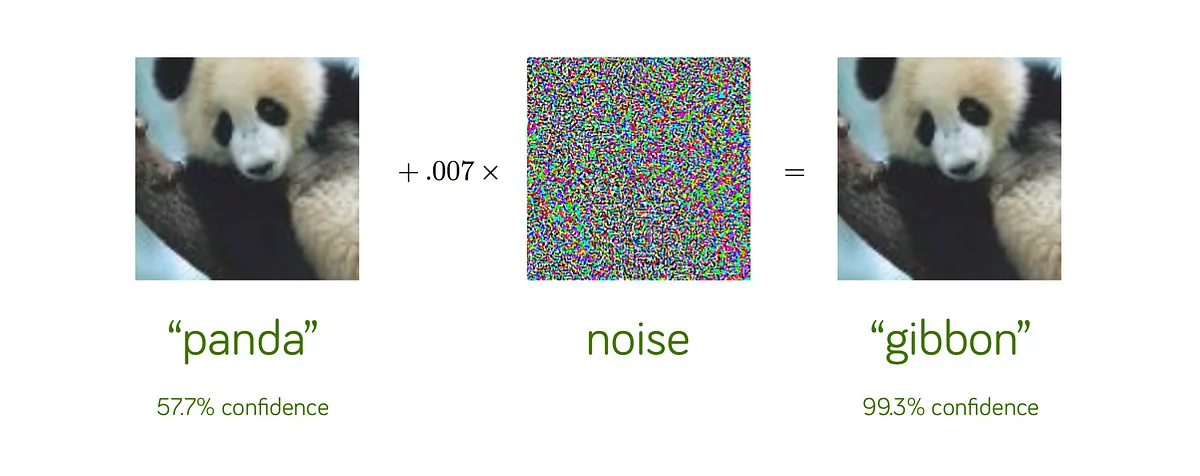

Adversarial Robustness: Adversarial attacks, involving small imperceptible changes to input images, can lead to incorrect predictions. These vulnerabilities pose risks for applications like autonomous vehicles and security systems, where accuracy is critical [180].

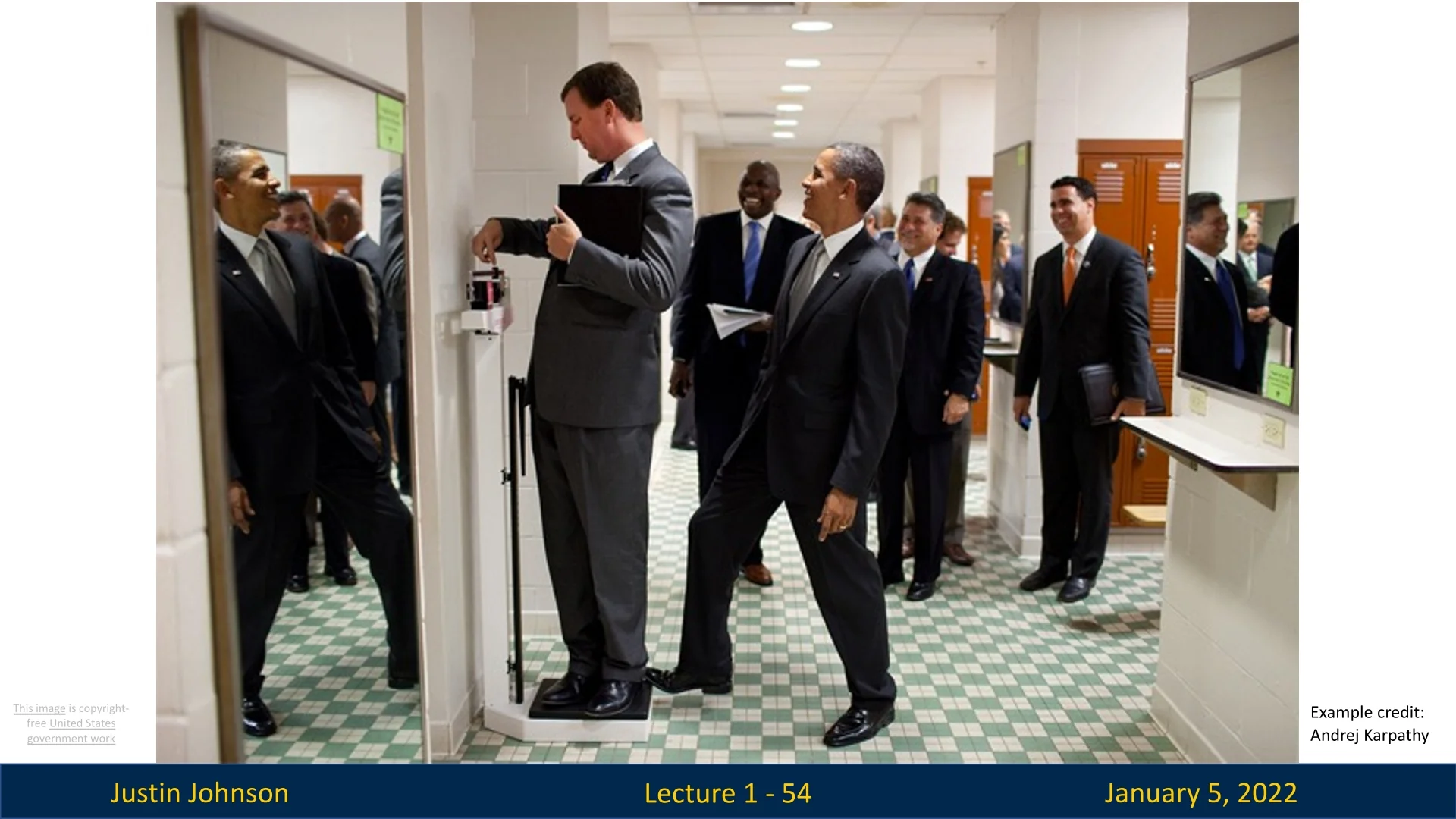

Figure 1.26: Adversarial examples: Adding imperceptible noise to a panda image causes the model to misclassify it [180]. - Complex Scene Understanding: Current CV models struggle to grasp nuanced scenes that are intuitive to humans. For instance, a situation where President Obama pranks a man by tipping a scale, causing everyone in the room to laugh, is easily understood by humans but perplexes AI, which lacks contextual and social understanding.

Future Directions:

- Enhancing Interpretability: Developing models that can explain their predictions to users will increase trust and usability in critical domains like healthcare and criminal justice.

- Mitigating Bias: Building datasets that are diverse and inclusive can reduce biases and ensure fairer outcomes across demographics.

- Improving Robustness: Advancing defenses against adversarial attacks will make CV systems more reliable in high-stakes scenarios.

- Integrating Contextual Reasoning: Multi-modal approaches that combine visual, textual, and other data streams can help systems understand complex social and environmental contexts.

While these challenges highlight the current limitations, they also present opportunities for groundbreaking advancements, bringing computer vision closer to human-like understanding.