Lecture 15: Image Segmentation

15.1 From Object Detection to Segmentation

In the previous chapter, we explored object detection, where the goal was to localize and classify objects within an image using bounding boxes. Object detection models such as Faster R-CNN [523] and YOLO [518] predict discrete object regions but do not assign labels to every pixel. However, many real-world applications require a finer-grained understanding beyond bounding boxes. This leads us to the problem of image segmentation, where the task is to assign a category label to every pixel in the image.

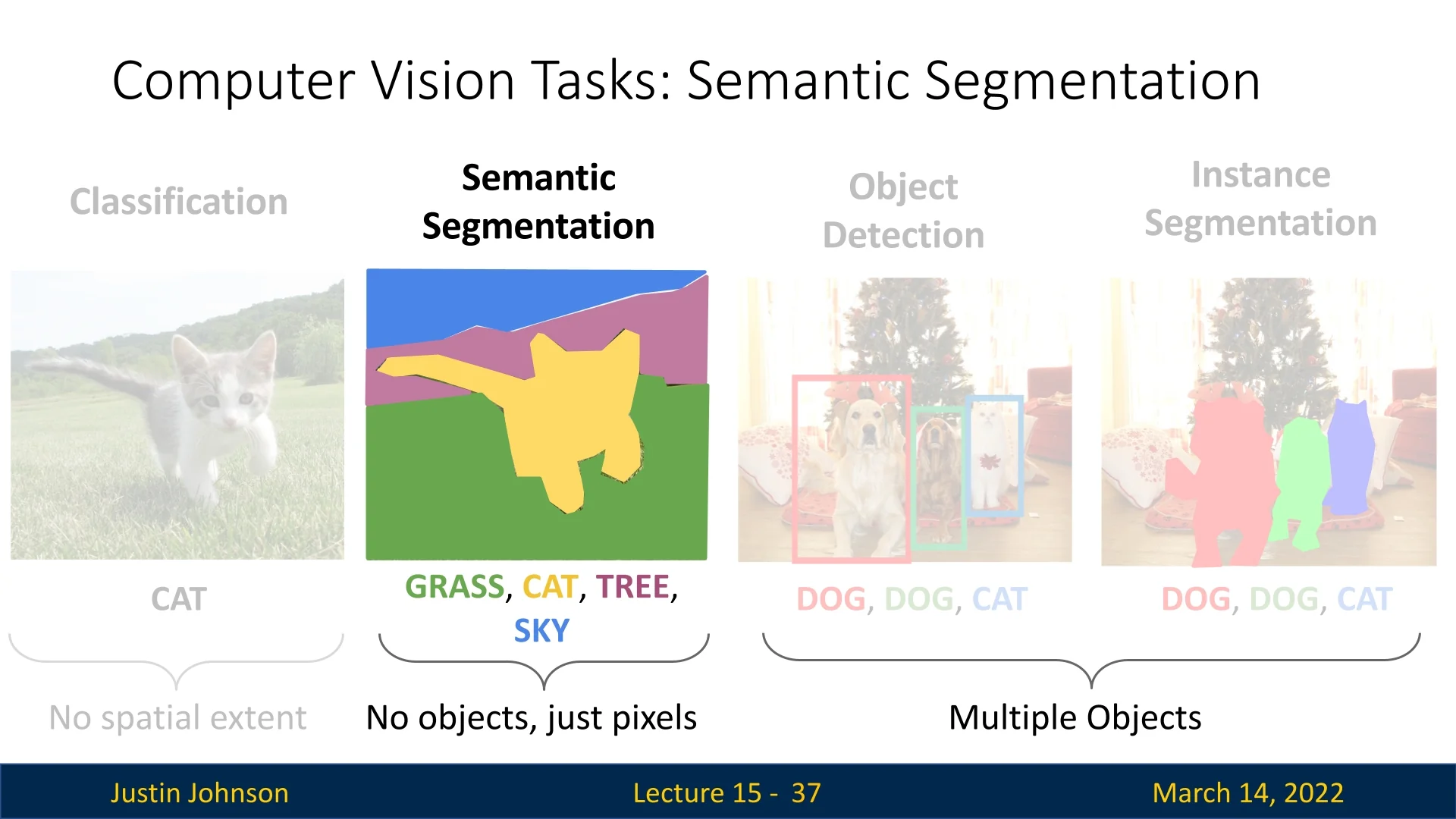

As shown in Figure 15.1, segmentation can be divided into two primary tasks:

- Semantic segmentation: Assigns a category label to each pixel but does not differentiate between instances of the same class.

- Instance segmentation: Extends semantic segmentation by distinguishing individual object instances.

We begin by studying semantic segmentation because it serves as the foundation for understanding pixel-wise classification. Unlike instance segmentation, which requires distinguishing between different objects of the same category, semantic segmentation focuses solely on identifying the type of object at each pixel. By first mastering the fundamental principles of pixel-wise classification, we can later build upon them to incorporate instance-level distinctions.

Enrichment 15.2: Why is Object Detection Not Enough?

Consider an autonomous vehicle navigating through a crowded urban environment. Object detection is a crucial first step: it draws bounding boxes around pedestrians, vehicles, and traffic signs, and already provides coarse spatial awareness (for example, that a pedestrian is somewhere near the curb rather than in the middle of the road). However, this level of understanding is still not sufficient for safe, fine-grained decision-making:

- Bounding boxes are coarse approximations. A bounding box is a rectangle that roughly encloses an object, not its true shape. In many cases this is enough to know that a pedestrian is “near the road”, but in safety-critical edge cases—such as a foot just crossing the curb versus standing safely on the sidewalk—the box does not reveal the precise contact boundary between pedestrian and road.

- Occlusions and overlaps create ambiguity. When objects overlap (e.g., a cyclist partially hidden behind a parked car), their bounding boxes may intersect or fragment. From boxes alone, it is hard to infer which pixels belong to which object, who is in front or behind, and exactly where the free space lies between them.

- No labels for “stuff” and free space. Object detection focuses on discrete, countable “things” (cars, pedestrians, traffic lights), but leaves the background unlabeled. It does not differentiate drivable road surface from sidewalks, bike lanes, grass, or curbs at the pixel level, even though this information is crucial for path planning and rule-following (e.g., staying within the lane markings).

Semantic segmentation addresses these limitations by assigning a class label to every pixel in the image. Instead of just knowing that “there is a pedestrian in this box,” the model produces a dense map indicating exactly which pixels are road, sidewalk, pedestrian, car, or building. This pixel-wise understanding provides the geometric and contextual detail needed for precise obstacle avoidance, free-space estimation, and safe navigation in complex scenes.

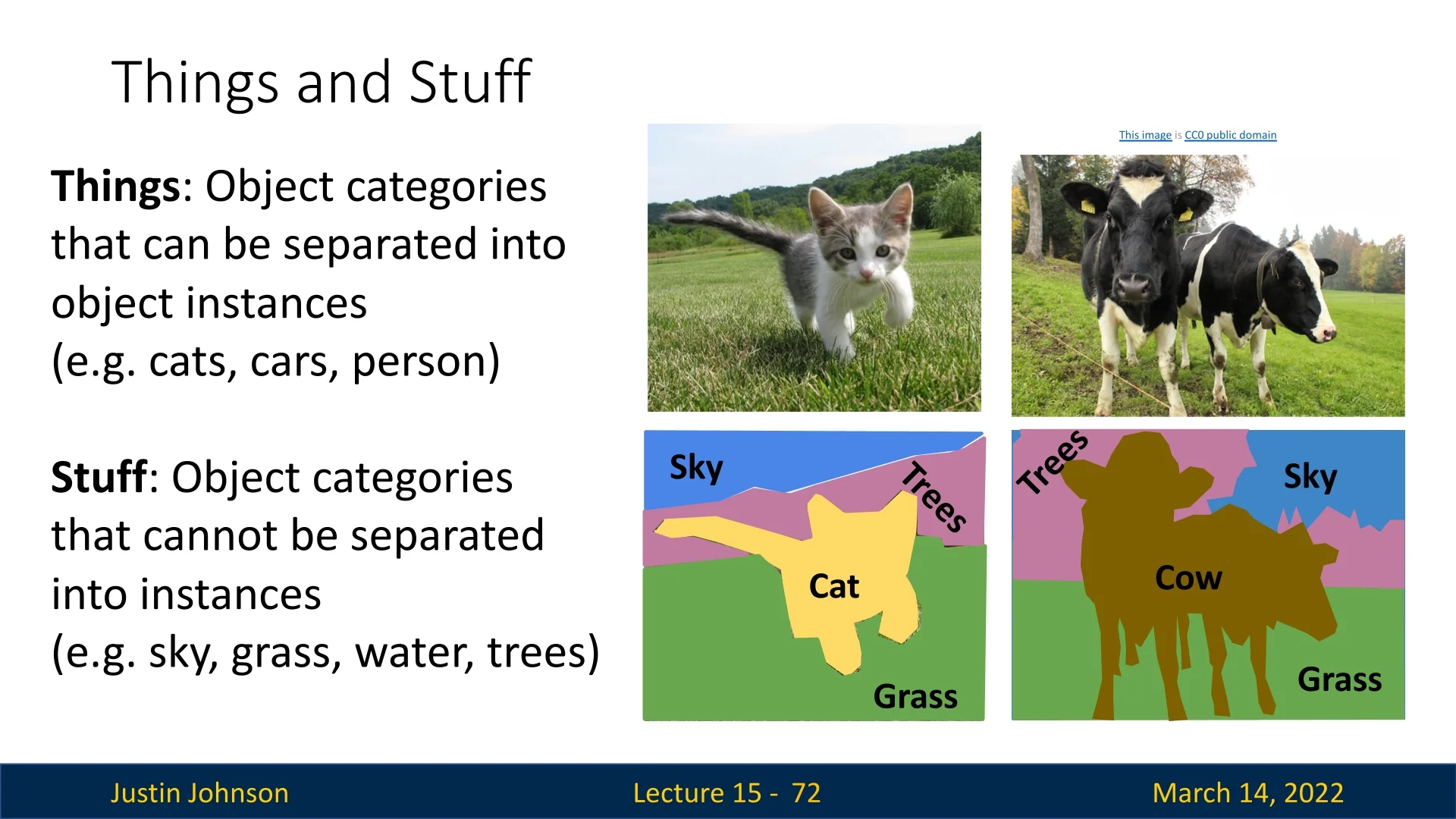

In Figure 15.2, we see a breakdown of image elements into things (object categories that can be separated into instances, such as cars, pedestrians, trees) and stuff (regions that lack clear boundaries, such as sky, road, grass). This pixel-level distinction enables applications such as lane detection, drivable area estimation, and pedestrian tracking, all of which contribute to safer and more efficient navigation.

The next sections will cover the fundamental methods used in segmentation, beginning with semantic segmentation, before proceeding to instance segmentation.

15.3 Advancements in Semantic Segmentation

In this section, we explore the evolution of semantic segmentation techniques, focusing on solutions that are convolutional neural networks (CNNs) based, reaching to more contemporary architectures. While CNNs have been foundational in image processing tasks, recent advancements indicate that transformer-based models have achieved superior accuracy in segmentation tasks, including semantic segmentation. These will only be discussed in future parts of this document.

15.2.1 Early Approaches: Sliding Window Method

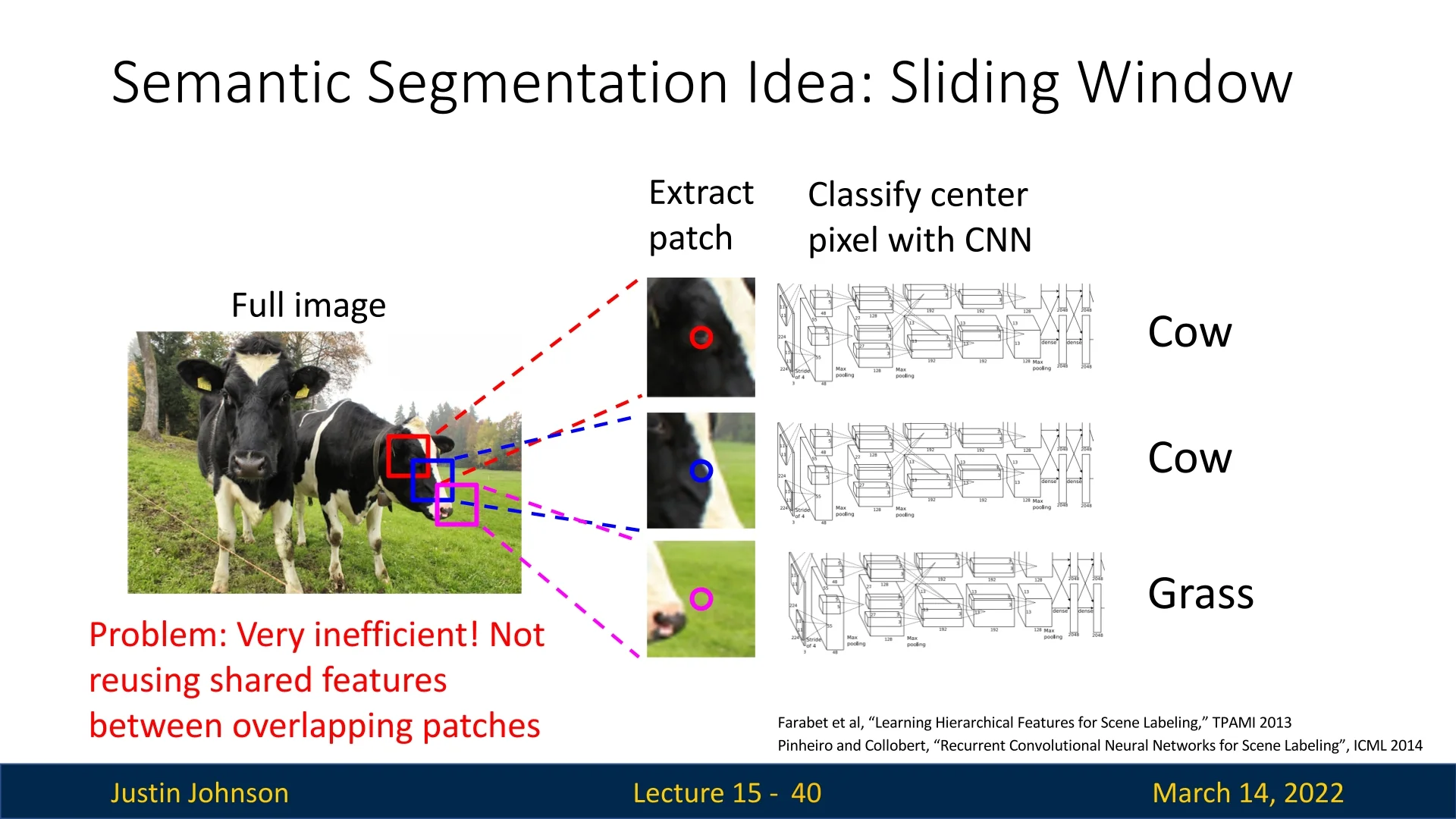

A straightforward yet inefficient approach to semantic segmentation involves the sliding window technique. In this method, for each pixel in the image, a patch centered around the pixel is extracted and classified using a CNN to predict the category label of the center pixel.

As depicted in Figure 15.3, this approach is computationally expensive because it fails to reuse shared features between overlapping patches, leading to redundant calculations.

15.2.2 Fully Convolutional Networks (FCNs)

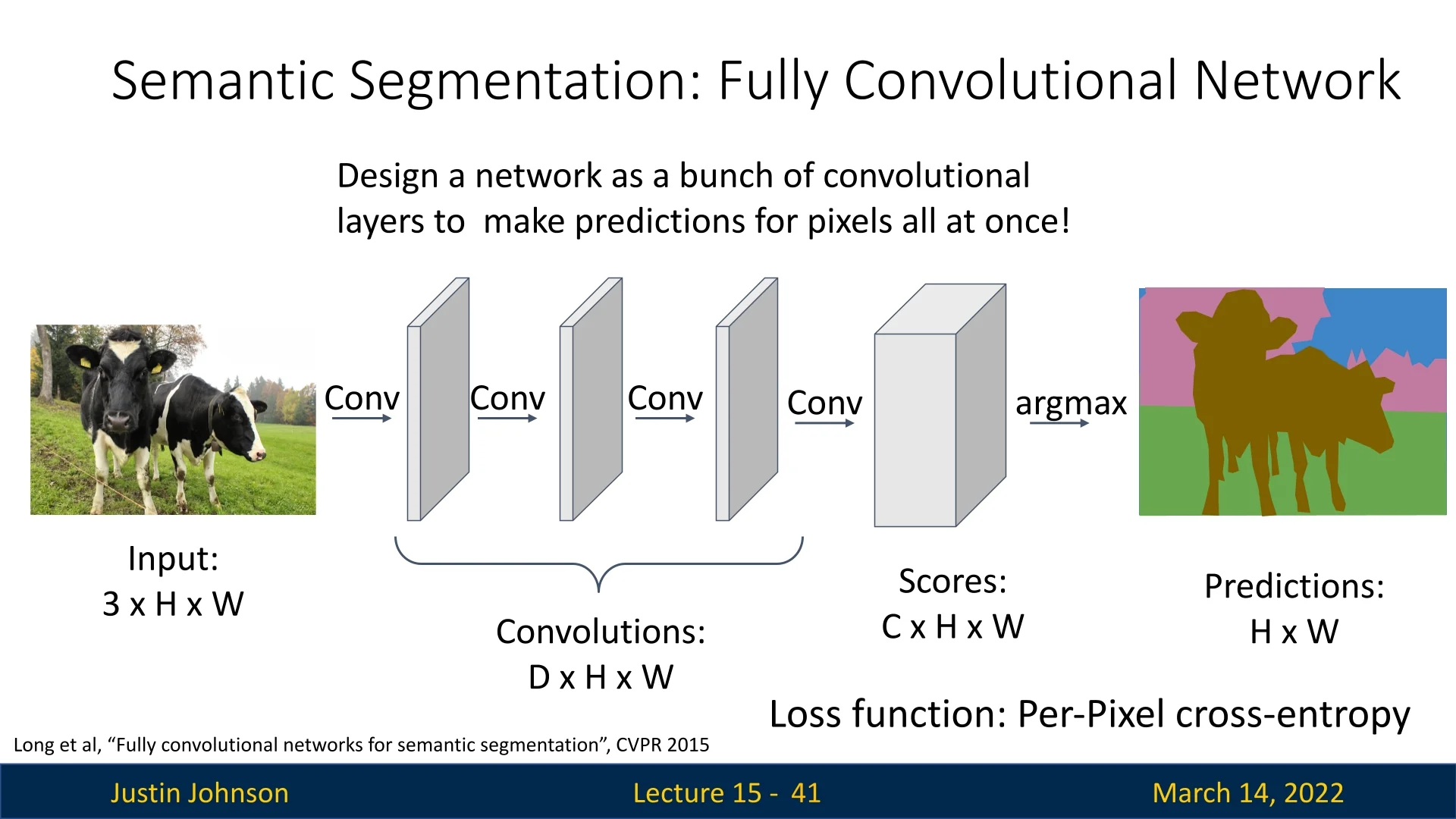

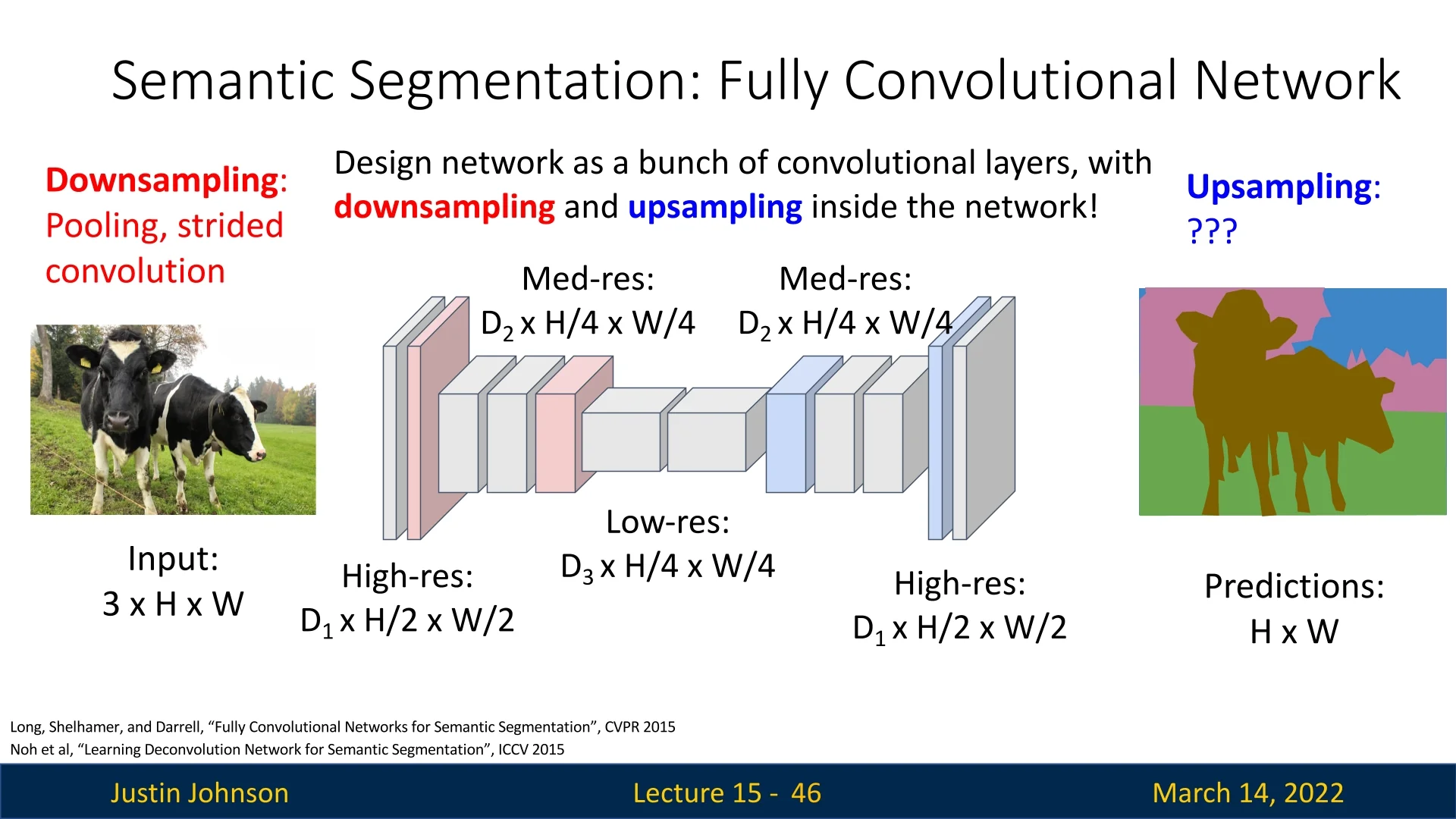

To address the inefficiencies of the sliding window method, Fully Convolutional Networks (FCNs) were introduced to the task [390]. FCNs utilize a fully convolutional backbone to extract features from the entire image, maintaining the spatial dimensions throughout the layers by employing same padding and 1x1 convolutions. The network outputs a feature map with dimensions corresponding to the input image, where each channel represents a class. The final classification for each pixel is obtained by applying a softmax function followed by an argmax operation across the channels.

Training is conducted using a per-pixel cross-entropy loss, comparing the predicted class probabilities to the ground truth labels for each pixel.

15.2.3 Challenges in FCNs for Semantic Segmentation

Despite their advancements, FCNs encounter specific challenges:

- Limited Receptive Field: The effective receptive field size grows linearly with the number of convolutional layers. For instance, with \(L\) layers of 3x3 convolutions, the receptive field is \(1 + 2L\), which may be insufficient for capturing global context.

- Computational Cost: Performing convolutions on high-resolution images is computationally intensive. Architectures like ResNet address this by aggressively downsampling the input, but this can lead to a loss of spatial detail.

15.2.4 Encoder-Decoder Architectures

To overcome these challenges, encoder-decoder architectures have been proposed, such as the model by Noh et al. [454]. These networks consist of two main components:

- Encoder: A series of convolutional and pooling layers that progressively downsample the input image, capturing high-level semantic features while expanding the receptive field.

- Decoder: A sequence of upsampling operations, including unpooling and deconvolutions, that restore the spatial dimensions to match the original input size, enabling precise localization for segmentation.

The encoder captures rich, abstract feature representations by reducing spatial resolution while increasing feature depth, whereas the decoder reconstructs fine-grained spatial details necessary for accurate per-pixel predictions.

While this encoder-decoder design is applied here for semantic segmentation, it is a widely used architectural pattern in deep learning and extends to many other tasks. For example:

- Machine Translation: Transformer-based sequence-to-sequence models such as T5 [501] and BART [324] employ an encoder to process input text and a decoder to generate translated output.

- Medical Image Analysis: U-Net [532] applies an encoder-decoder structure for biomedical image segmentation, achieving precise boundary delineation in tasks like tumor segmentation.

- Anomaly Detection: Autoencoders use an encoder to learn compressed feature representations and a decoder to reconstruct inputs, enabling anomaly detection by identifying discrepancies between the input and reconstruction.

- Super-Resolution and Image Generation: Models like SRGAN [317] employ an encoder to extract image features and a decoder to generate high-resolution outputs.

As we continue, we will encounter various adaptations of this fundamental encoder-decoder structure, each tailored to the specific requirements of different tasks.

15.4 Upsampling and Unpooling

To enhance spatial resolution in feature maps, we employ upsampling techniques. Until now in this course, we have not introduced any method for systematically enlarging the spatial dimensions of tensors in a meaningful way. While we previously used bilinear interpolation to project proposals onto feature maps after downsampling ([ref]), we have yet to explore how such techniques can be adapted for general upsampling—something we will examine in later sections.

Although we can increase tensor size using zero-padding along the borders, this does not introduce any new spatial information or recover lost details, making it ineffective for true upsampling. Instead, we require dedicated upsampling methods that intelligently restore missing details while preserving spatial coherence. Throughout this section, we will explore various approaches that allow us to increase resolution effectively, ensuring that the upsampled feature maps retain meaningful information.

Do Interpolated Pixels Need to be “Valid” Image Values?

All of the upsampling and unpooling methods we have discussed (nearest neighbor, bilinear, bicubic, transposed convolution, etc.) operate in continuous space: they produce real-valued outputs by combining neighboring pixels or features with real-valued weights. This naturally raises two related questions:

- 1.

- What happens if the resulting pixel/feature values are non-integer or fall outside the usual image range?

- 2.

- When (if ever) do we need to enforce that the upsampled result is a valid image (e.g., integer RGB values in \([0, 255]\))?

Inside a neural network: real-valued feature maps are perfectly fine Within a convolutional network, tensors represent features, not necessarily display-ready images. In this setting:

- Feature maps are typically stored as 32-bit floating-point values, and can take on any real value (positive or negative, large or small).

- Upsampling operations (nearest neighbor, bilinear, bicubic, transposed convolution) simply produce new floating-point values. There is no requirement that these be integers or lie within a specific range; subsequent layers and nonlinearities will transform them further.

- Any normalization or scaling applied to the input (e.g., mapping RGB values from \([0,255]\) to \([0,1]\) or standardizing to zero mean and unit variance) is usually inverted only at the very end, if we want to visualize or save an image.

From this perspective, “non-integer” or slightly out-of-range values are not a problem at all during intermediate processing: the network is trained end-to-end to work with these continuous-valued feature maps.

At the output: producing a valid image for visualization or storage

The situation changes when the goal is to produce a valid image as the final output (e.g., in super-resolution, image-to-image translation, or generative models). In that case, we typically want:

- Pixel values in a fixed range (for example \([0,1]\) or \([0,255]\)).

- Integer-valued pixels if we are saving to standard formats (e.g., 8-bit uint8 RGB).

Common strategies in this case are:

- Constrain the range with an activation: Use a final activation such as \(\sigma (\cdot )\) (sigmoid) to map outputs to \([0,1]\), or \(\tanh (\cdot )\) to map to \([-1,1]\). During training, the loss is computed against normalized target images in the same range.

-

Post-processing after the network: Allow the network to output unconstrained real values, then:

- 1.

- De-normalize (invert any input normalization, e.g. multiply by standard deviation and add mean).

- 2.

- Clamp values to the valid range, e.g. \(\mbox{pixel} \leftarrow \min (\max (\mbox{pixel}, 0), 1)\) or \([0,255]\).

- 3.

- Quantize to integers if needed, e.g. \(\mbox{pixel}_{\mbox{uint8}} = \mbox{round}(255 \cdot \mbox{pixel}_{[0,1]})\).

- Handling overshoot in higher-order interpolation: Methods like bicubic interpolation can produce values slightly outside the original range (due to oscillatory cubic kernels). In classical image processing and in deep learning code, the standard remedy is simple clamping before display or saving.

In other words, when we care about producing a valid, displayable image, validity is enforced at the very end by range restriction and (optionally) quantization—not by changing the upsampling method itself.

Summary: feature maps vs. final images To summarize:

- For internal feature maps, non-integer and even slightly out-of-range values are entirely acceptable; the network treats them as continuous signals and learns to use them.

- For final image outputs, we typically normalize during training and then de-normalize, clamp to a valid range, and quantize at inference time to obtain a proper image representation (e.g., 8-bit RGB).

Thus, all of the upsampling and unpooling methods discussed in this chapter can be used without modification inside a network; concerns about “valid pixels” are addressed at the output layer or in a simple post-processing step when we need a real image rather than a learned feature map.

A crucial variant of upsampling is unpooling, which aims to reverse the effects of pooling operations. While pooling reduces resolution by discarding spatial details, unpooling attempts to restore them, facilitating fine-grained reconstruction of object boundaries. However, unpooling alone is often insufficient for producing smooth and accurate feature maps, as it merely places values in predefined locations without estimating missing information. This can result in reconstruction gaps, blocky artifacts, or unrealistic textures. As we will see, more advanced upsampling techniques address these shortcomings by incorporating interpolation and learnable transformations.

In the decoder architecture proposed by Noh et al., unpooling plays a fundamental role in progressively recovering lost spatial information. It bridges the gap between the high-level semantic representations learned by the encoder and the dense, pixel-wise predictions required for precise classification.

In the following sections, we explore various upsampling strategies, beginning with fundamental unpooling techniques and gradually progressing toward more advanced methods.

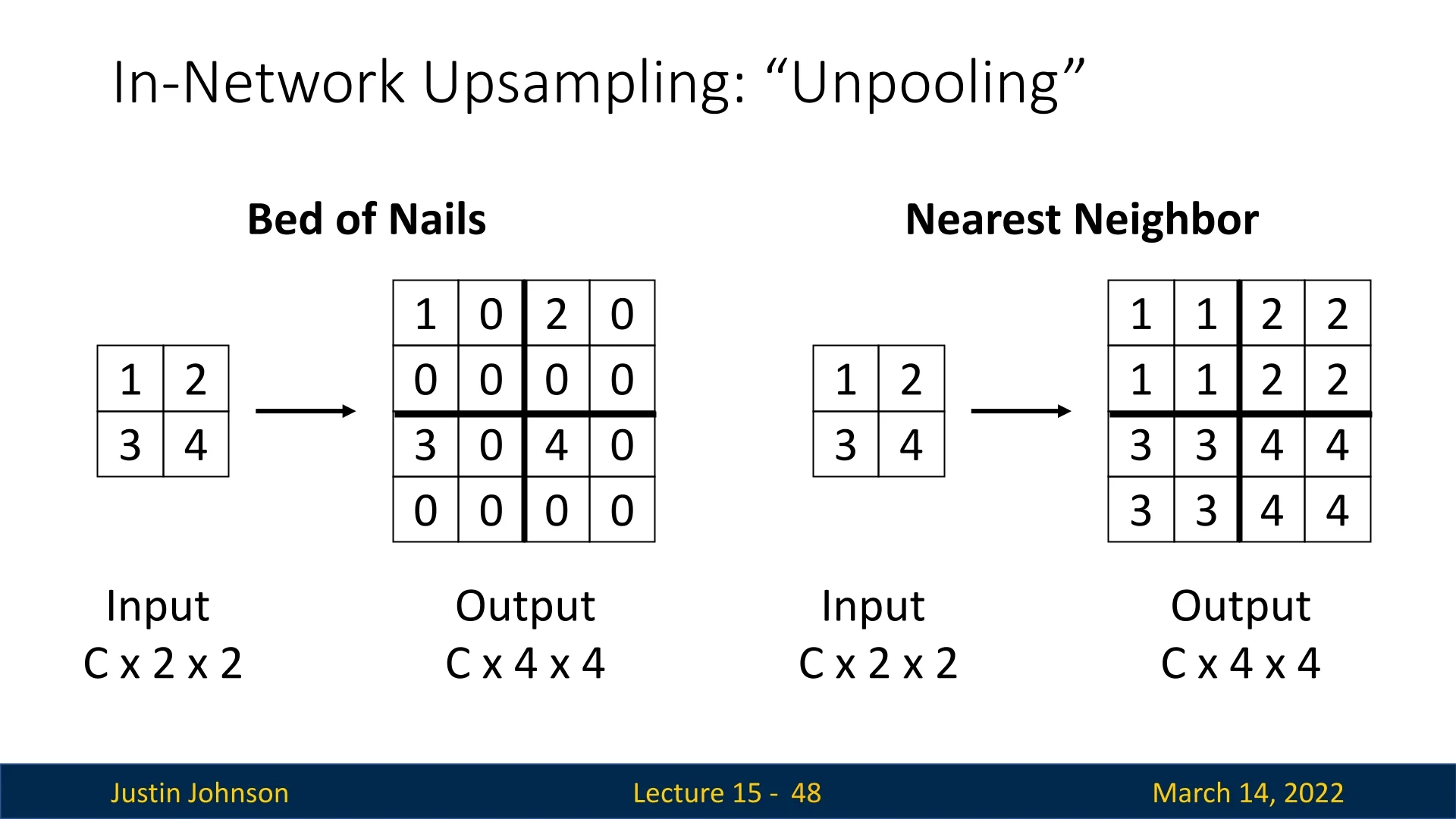

15.3.1 Bed of Nails Unpooling

One of the simplest forms of unpooling is known as Bed of Nails unpooling. To illustrate the concept, consider the following example: We’re given an input tensor of size \(C \times 2 \times 2\), and our objective is to produce an output tensor of size \(C \times 4 \times 4\).

The method follows these steps:

- An output tensor of the desired size is initialized with all zeros.

- The output tensor is partitioned into non-overlapping regions, each corresponding to a single value from the input tensor. The size of these regions is determined by the upsampling factor \(s\), which is the ratio between the spatial dimensions of the output and the input. For example, if the input is \(H \times W\) and the output is \(sH \times sW\), then each region in the output has size \(s \times s\).

- Each value from the input tensor is placed in the upper-left corner of its corresponding region in the output.

- All remaining positions are left as zeros.

The term ”Bed of Nails” originates from the characteristic sparse structure of this unpooling method, where non-zero values are positioned in a regular grid pattern, resembling nails protruding from a flat surface.

Limitations of Bed of Nails Unpooling While conceptually simple, Bed of Nails unpooling suffers from a critical flaw: it introduces severe aliasing, which significantly degrades the quality of the reconstructed feature maps. By sparsely placing input values into an enlarged output tensor and filling the remaining positions with zeros, this method results in a highly discontinuous representation with abrupt intensity changes. These gaps introduce artificial high-frequency components, making it difficult to recover fine spatial details and leading to distorted reconstructions.

The primary drawbacks of Bed of Nails unpooling are:

- Sparse Representation: The method leaves large gaps of zeros between meaningful values, creating an unnatural, high-frequency pattern that distorts spatial information.

- Abrupt Intensity Shifts: The sharp transitions between non-zero values and surrounding zeros introduce edge artifacts, leading to aliasing effects such as jagged edges and moiré patterns.

- Loss of Fine Detail: The lack of interpolation prevents smooth reconstructions, making it difficult to recover object boundaries and subtle spatial features.

Because of these limitations, Bed of Nails unpooling is rarely used in practice. Its inability to provide a smooth, information-preserving reconstruction makes it unsuitable for tasks requiring high-quality feature map upsampling.

15.3.2 Nearest-Neighbor Unpooling

A more practical alternative to Bed of Nails unpooling is Nearest-Neighbor unpooling. Instead of placing a single value in the upper-left corner and filling the rest with zeros, this method copies the value across the entire corresponding region, ensuring a more continuous feature map.

The key advantages of Nearest-Neighbor unpooling include:

- Smoother Transitions: By replicating values across the upsampled regions, Nearest-Neighbor unpooling maintains spatial continuity. In contrast, Bed of Nails unpooling introduces sharp jumps between non-zero values and large zero-filled areas, which disrupts smooth feature propagation.

- Reduced Aliasing: The discontinuities introduced by zero-padding in Bed of Nails unpooling create artificial high-frequency patterns, leading to jagged edges and moiré artifacts. Nearest-Neighbor unpooling minimizes these distortions by ensuring a more uniform intensity distribution.

- Better Feature Preservation: Copying values instead of inserting zeros retains more useful information about the original feature map. Since features remain continuous rather than fragmented by empty gaps, spatial relationships between objects are better preserved.

These properties make Nearest-Neighbor unpooling a more effective choice than Bed of Nails, particularly for reducing aliasing effects. By ensuring smoother transitions and preventing artificial high-frequency noise, it produces cleaner and more reliable feature maps, making it more suitable for deep learning applications.

However, Nearest-Neighbor unpooling still has limitations. Since it simply copies values, it can produce blocky (unsmooth) artifacts and lacks the ability to generate new information between upsampled pixels. This makes it unsuitable for capturing fine details, especially when dealing with natural images or complex textures.

To achieve better reconstructions, more advanced upsampling methods are used. These include:

- Bilinear Interpolation: A smoother alternative that interpolates pixel values using a weighted average of neighboring points. We’ve already covered it extensively.

- Bicubic Interpolation: Extends bilinear interpolation by considering more neighbors and applying cubic functions for higher-quality results.

- Max Unpooling: A structured approach that retains important features by reversing pooling operations using stored indices.

- Transposed Convolution: A learnable upsampling technique that enables neural networks to reconstruct detailed feature maps through trainable filters.

In the following parts, we will explore each of these methods, highlighting their advantages and trade-offs in deep learning applications.

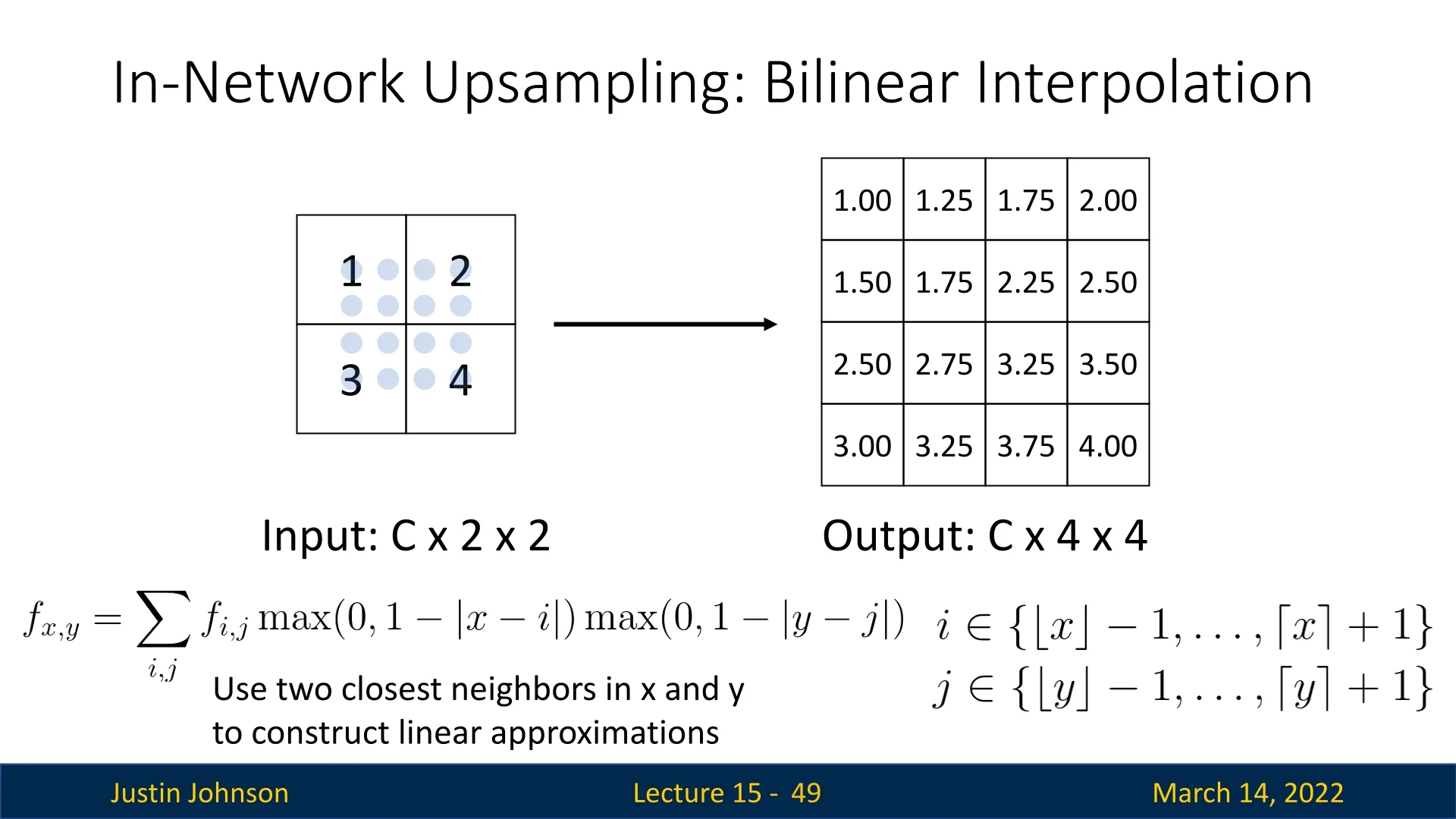

15.3.3 Bilinear Interpolation for Upsampling

While nearest-neighbor unpooling provides a simple way to upsample feature maps, it often introduces blocky artifacts due to the direct replication of values. A more refined approach is bilinear interpolation, which estimates each output pixel as a weighted sum of its surrounding neighbors, resulting in a smoother reconstruction.

Consider an input feature map of shape \(C \times H \times W\) and an output of shape \(C \times H' \times W'\), where the spatial dimensions are enlarged (\(H' > H\), \(W' > W\)). Unlike unpooling, which places values at predefined locations without interpolation, bilinear interpolation calculates each pixel’s intensity by considering its four nearest neighbors in the original input feature map.

Bilinear Interpolation: Generalized Case

Given an input feature map \(\mathbf {I}\) of size \(C \times H \times W\), we

define an upsampled feature map \(\mathbf {I'}\) of size \(C \times H' \times W'\).

To compute the value of a pixel at a location \((x', y')\) in the upsampled output, we follow these steps:

- Mapping to the Input Grid: The coordinate \((x', y')\) in the output feature map is mapped back to the corresponding position \((x, y)\) in the input space using the scaling factors: \[ x = \frac {x' (W - 1)}{W' - 1}, \quad y = \frac {y' (H - 1)}{H' - 1} \] where \(W'\) and \(H'\) are the new width and height, and \(W, H\) are the original dimensions.

- Identifying Neighboring Pixels: The four closest integer grid points that enclose \((x, y)\) are determined as: \[ a = (x_0, y_0), \quad b = (x_0, y_1), \quad c = (x_1, y_0), \quad d = (x_1, y_1) \] where: \[ x_0 = \lfloor x \rfloor , \quad x_1 = \lceil x \rceil , \quad y_0 = \lfloor y \rfloor , \quad y_1 = \lfloor y \rfloor . \] These four points form a bounding box around \((x, y)\).

- Computing the Interpolation Weights: Each neighboring pixel contributes to the final interpolated value based on its distance to \((x, y)\). The interpolation weights are computed as: \[ w_a = (x_1 - x) (y_1 - y), \quad w_b = (x_1 - x) (y - y_0) \] \[ w_c = (x - x_0) (y_1 - y), \quad w_d = (x - x_0) (y - y_0). \]

-

Normalization: To ensure that the weights sum to one, we apply a normalization factor: \[ \mbox{norm_const} = \frac {1}{(x_1 - x_0)(y_1 - y_0)}. \]

- Computing the Interpolated Value: The final interpolated intensity at \((x', y')\) is then computed as: \[ I'(x', y') = w_a I_a + w_b I_b + w_c I_c + w_d I_d. \]

Advantages and Limitations of Bilinear Interpolation

Bilinear interpolation offers clear improvements over nearest-neighbor unpooling when upsampling feature maps or images. Instead of simply copying the nearest value, each output pixel is computed as a weighted average of its four closest input pixels, with weights determined by geometric distance. This produces smoother transitions, reduces blocky artifacts, and better preserves local spatial relationships than nearest-neighbor methods.

However, bilinear interpolation also has important limitations. Because it relies on only four neighbors and uses simple linear weighting, it tends to blur high-frequency details: fine textures, sharp edges, and small-scale patterns can become softened. In effect, bilinear interpolation trades off blockiness for smoothness, but at the cost of some sharpness and detail.

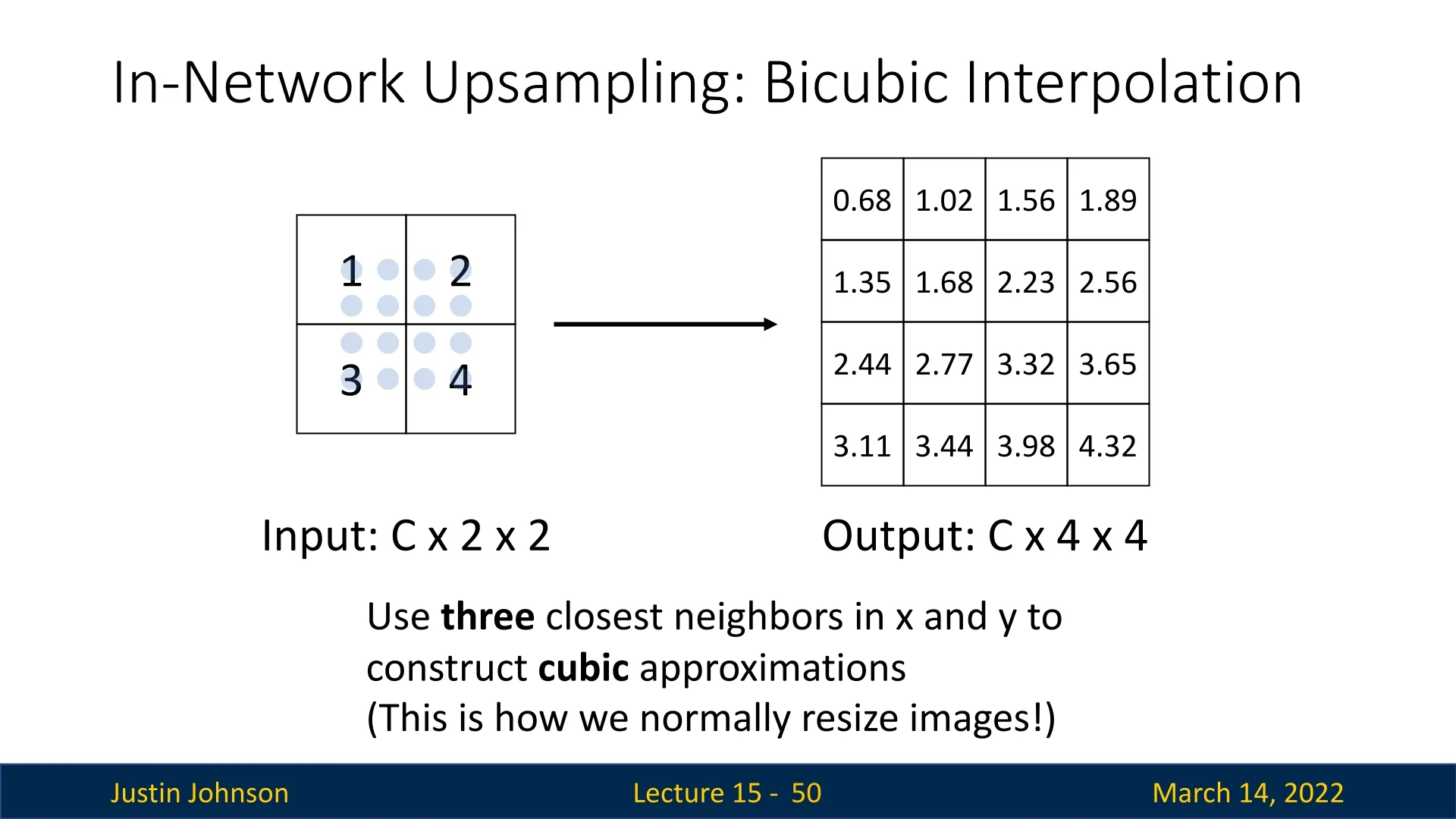

15.3.4 Bicubic Interpolation for Upsampling

Bicubic interpolation is a more advanced alternative to nearest-neighbor or bilinear upsampling. Instead of using just four neighbors, bicubic interpolation considers a \(4 \times 4\) neighborhood (16 pixels) around each output position and applies a cubic weighting function along each axis. This broader context and smoother weighting scheme allow the method to better respect local structure and produce sharper, more detailed upsampled results.

Why Bicubic Interpolation?

The wider support of bicubic interpolation directly addresses the limitations of bilinear interpolation. By aggregating information from sixteen neighboring pixels and using cubic (rather than linear) weights, bicubic interpolation can better preserve edges, reduce blurring, and maintain fine textures. For this reason, it is commonly used as a high-quality default for image resizing and is often preferred in deep learning pipelines when visually faithful, detail-preserving upsampling is important.

Mathematical Reasoning

Bicubic interpolation extends bilinear interpolation by introducing a cubic weighting function that smoothly distributes the contribution of each neighboring pixel. While bilinear interpolation assigns weights based purely on distance (linearly decreasing to zero), the cubic approach tailors these weights using a function that decays gradually, allowing pixels farther from the target position to still have a small but meaningful influence.

The commonly used weighting function is piecewise-defined:

\[ W(t) = \begin {cases} (a + 2)|t|^3 - (a + 3)|t|^2 + 1, & 0 \leq |t| < 1, \\ a|t|^3 - 5a|t|^2 + 8a|t| - 4a, & 1 \leq |t| < 2, \\ 0, & |t| \geq 2, \end {cases} \]

where \(a\) typically takes values around \(-0.5\) to balance smoothness and sharpness. The function ensures nearby pixels carry the most weight, while more distant neighbors still contribute smoothly rather than being abruptly excluded.

A concise visual and conceptual explanation can be found in this Computerphile video.

Bicubic Interpolation: Generalized Case

Assume we have an input feature map \(\mathbf {I}\) of size \(C \times H \times W\), and we wish to produce an upsampled map \(\mathbf {I'}\) of size \(C \times H' \times W'\). The bicubic interpolation proceeds as follows:

- 1.

- Coordinate Mapping: Map the output pixel location \((x',y')\) back to the corresponding floating-point coordinate \((x,y)\) in the input grid: \[ x = \frac {x'(W - 1)}{W' - 1}, \quad y = \frac {y'(H - 1)}{H' - 1}. \]

- 2.

- Neighbor Identification: Determine the \(\pm 1\) and \(\pm 2\) offsets around \(\lfloor x \rfloor \) and \(\lfloor y \rfloor \). This yields a \(4 \times 4\) set of pixels \(\{I_{i,j}\}\) centered near \((x,y)\).

- 3.

- Applying the Cubic Weights: Use the cubic function \(W(t)\) in both the \(x\) and \(y\) directions: \[ I'(x', y') = \sum _{i=-1}^{2}\sum _{j=-1}^{2} W(x - x_i)\,W(y - y_j)\,I_{i,j}. \]

Advantages and Limitations

Sharper Details and Continuity. By sampling a larger neighborhood with a smoothly decaying weight function, bicubic interpolation preserves finer structures, reduces artifacts, and transitions more smoothly across pixel boundaries than bilinear interpolation.

Better Texture Preservation. Rather than over-smoothing, bicubic interpolation better maintains texture information by assigning fractional influences to pixels farther than one unit away.

Non-Learnable. Despite these benefits, bicubic interpolation remains a fixed formula that cannot adapt to complex or domain-specific feature distributions in deep learning.

In contrast, max unpooling or learnable upsampling layers (we’ll learn about those in the following parts) can dynamically capture where and how to upscale feature maps.

Hence, while bicubic interpolation offers a clear advantage over simpler methods for image resizing tasks, its fixed nature can be sub-optimal in end-to-end neural networks that require trainable, context-dependent upsampling.

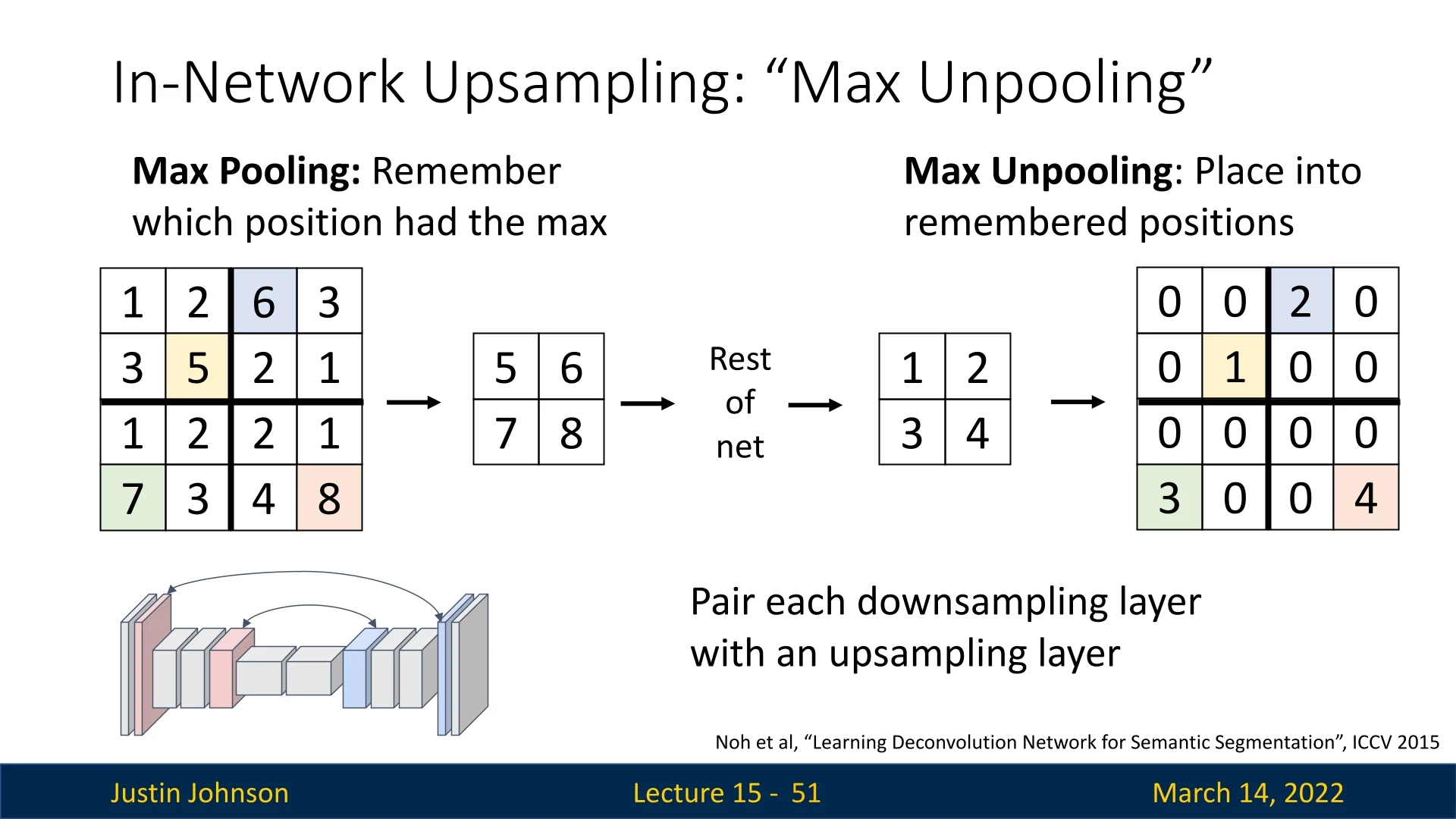

15.3.5 Max Unpooling

Max unpooling is an upsampling operation designed to “invert” max pooling as faithfully as possible. Instead of estimating new values via interpolation (as in bilinear or bicubic upsampling), max unpooling is a routing mechanism: it uses the indices of the maxima recorded during max pooling to place activations back into their original spatial locations, producing a sparse but geometrically aligned feature map.

Intuitively, max unpooling acts like a memory of where the network believed the most important responses were before downsampling. During encoding, max pooling keeps only the largest activation in each window and remembers where it came from. During decoding, max unpooling re-expands the feature maps and reinstates those activations exactly at the stored positions, filling all other locations with zeros. This preserves the encoder’s notion of “where things are” while deferring dense reconstruction to subsequent convolutions.

Max Unpooling in the DeconvNet of Noh et al. (ICCV 2015)

In the DeconvNet architecture proposed by Noh et al. [454], max unpooling layers are placed symmetrically to the max pooling layers of the encoder. Each pooling layer performs:

- Max pooling with switches: For each pooling window (e.g., \(2 \times 2\) with stride 2), the encoder selects the maximum activation and stores its index (row and column position) inside the window.

The corresponding max unpooling layer in the decoder then executes three conceptually simple steps:

- 1.

- Re-expand the spatial grid: The decoder allocates an upsampled feature map with the same spatial resolution as the pre-pooled feature map.

- 2.

- Place activations using indices: Each pooled activation is written back into the upsampled grid at the exact location indicated by its recorded index; all other positions in that pooling window are set to zero.

- 3.

- Refine sparsity via convolutions: This sparse, index-aligned map is passed through convolutional layers that propagate information from strong activations into nearby zero regions, gradually reconstructing dense feature maps and, ultimately, a segmentation mask.

This encoder–decoder symmetry has two important effects:

- It preserves spatial correspondence between encoder and decoder: high-level features in the decoder are anchored to the same image regions where they were originally detected.

- It provides a structured scaffold for reconstruction: strong activations sit at semantically meaningful positions (edges, parts, object interiors), and subsequent convolutions learn to fill in the details around them.

Why Max Unpooling is More Effective Than Bed of Nails Unpooling

Both max unpooling and Bed of Nails unpooling produce sparse feature maps that are later densified by convolutions, but they differ crucially in where activations are placed.

Spatial alignment versus arbitrary placement

- Bed of Nails unpooling copies each activation from the low-resolution feature map into a fixed, predetermined location in the corresponding upsampled block (for example, always the top-left corner of a \(2 \times 2\) region), setting all other positions to zero. This ignores where the activation originally occurred inside the pooling window. As a result, features are systematically shifted in space, breaking alignment between encoder and decoder.

- Max unpooling, by contrast, uses the stored pooling indices to place each activation back into its true pre-pooled location. The sparse pattern therefore matches the geometry induced by the encoder, preserving object shapes, boundaries, and part locations as seen by the max-pooling layers.

Why zeros in max unpooling are less problematic Both methods introduce many zeros, but their semantic meaning differs:

- In Bed of Nails unpooling, zeros are inserted according to a fixed pattern that does not reflect the encoder’s decisions. They appear between activations even in regions where several pixels were originally moderately strong but not maximal. The decoder then receives an artificial “checkerboard” structure: a regular grid of isolated nonzeros surrounded by zeros, which can induce aliasing and unnatural high-frequency patterns unless later convolutions work hard to undo these artifacts.

-

In Max unpooling, zeros appear precisely at positions that were not selected by max pooling. In other words, they encode the fact that, in that local window, no feature exceeded the chosen maximum at those positions.

This matches the encoder’s notion of saliency: strong responses are re-instated where they originally occurred, while weaker or background responses are suppressed. Subsequent convolutions can therefore treat zeros as “low-confidence” or “background” rather than as artificial gaps; they naturally diffuse information outward from the high-activation sites, producing smooth, context-aware reconstructions.

Structured reconstruction Because max unpooling respects the encoder’s spatial structure, the resulting sparse maps form a data-driven blueprint for reconstruction:

- Edges and object parts are reintroduced at approximately correct locations, giving decoder convolutions a meaningful starting point.

- There is no need to learn to correct systematic misalignment (as with Bed of Nails); learning can instead focus on refining shapes, filling in missing detail, and resolving ambiguities.

In summary, max unpooling remains a non-learnable upsampling operation, but by leveraging pooling indices it preserves the encoder’s spatial decisions. This makes it substantially more effective than Bed of Nails unpooling in fully convolutional decoders such as DeconvNet [454], where accurate alignment between downsampling and upsampling stages is crucial for high-quality semantic segmentation.

Bridging to Transposed Convolution

Max unpooling restores spatial activations efficiently, but it lacks the ability to generate new details or refine spatial features dynamically. Since it is a purely index-driven process, it cannot adaptively reconstruct missing information beyond what was retained during max pooling.

To overcome these limitations, we now explore transposed convolution, a learnable upsampling method that optimizes filter weights to produce high-resolution feature maps. This allows for fine-grained spatial reconstructions and greater adaptability compared to fixed unpooling strategies.

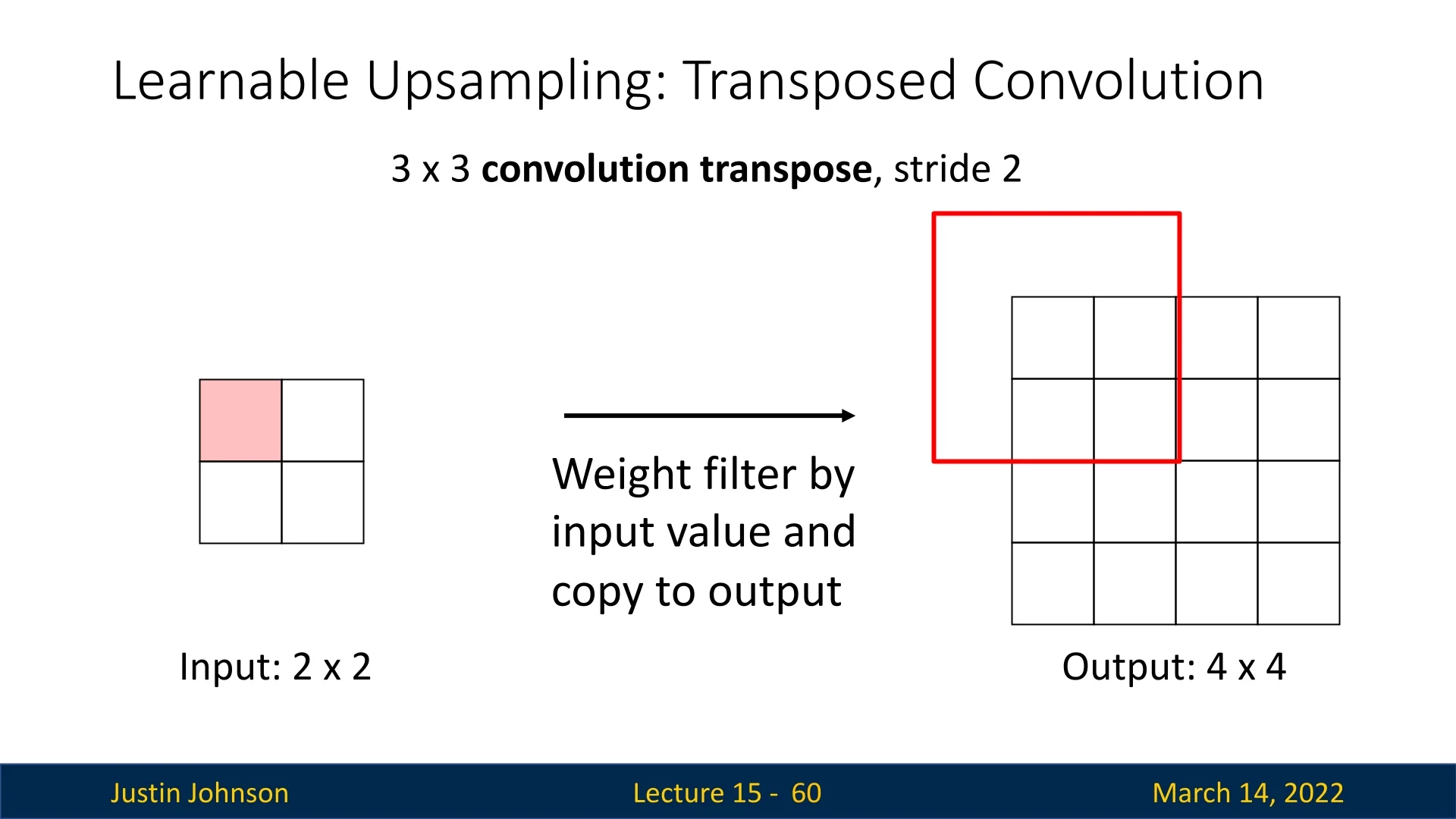

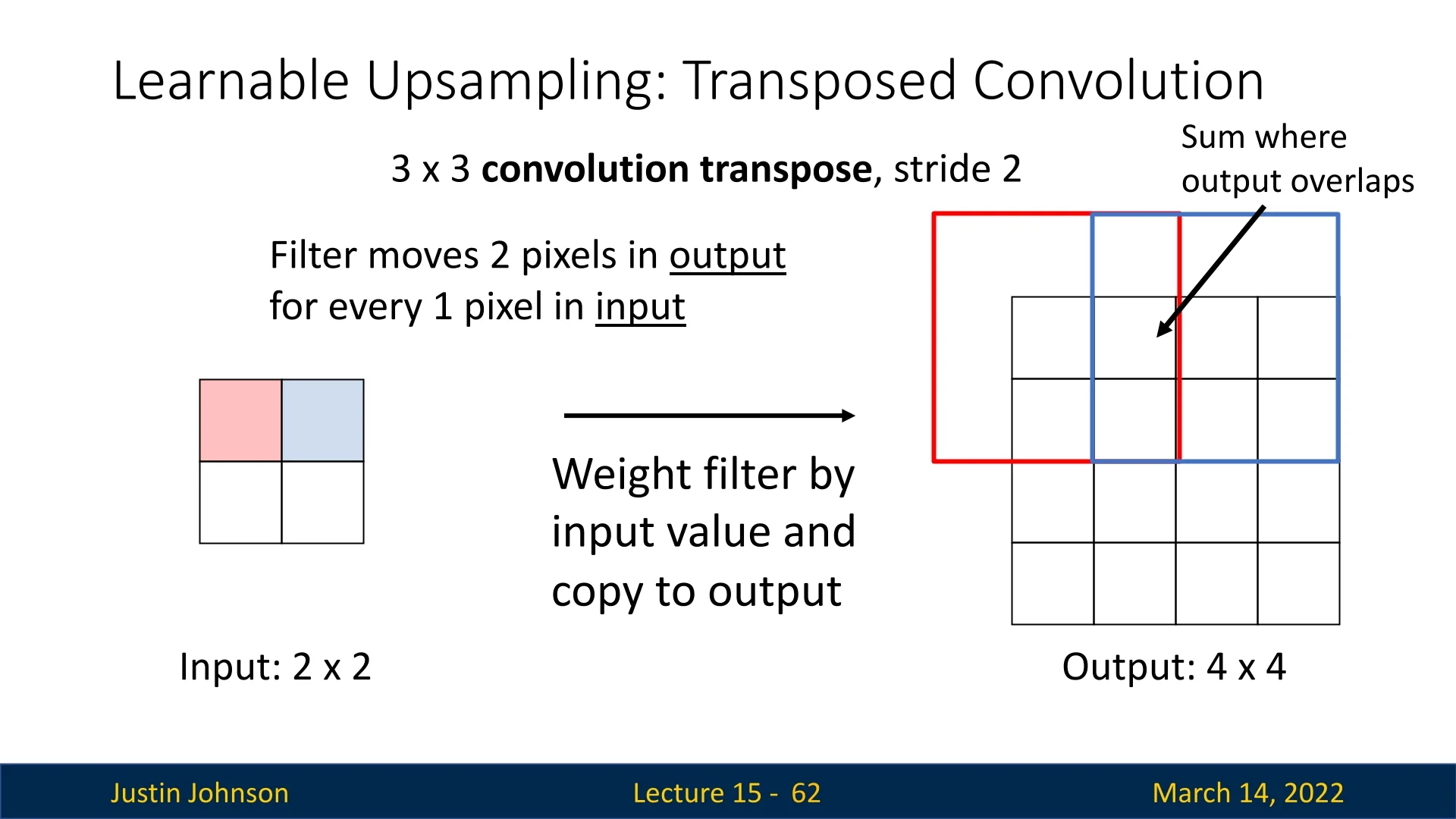

15.3.6 Transposed Convolution

Transposed convolution, also referred to as deconvolution or fractionally strided convolution, is an upsampling technique that enables the network to learn how to generate high-resolution feature maps from lower-resolution inputs.

Unlike interpolation-based upsampling or max unpooling, which are fixed operations, transposed convolution is learnable, meaning the network optimizes the filter weights to improve the reconstruction process.

Although called deconvolution, it is not an actual inversion of convolution. Instead, it follows a similar mathematical operation as standard convolution but differs in how the filter is applied to the input tensor.

Understanding the Similarity to Standard Convolution

In a standard convolutional layer, an input feature map is processed using a learned filter (kernel), which slides over the input using a defined stride. At each step, the filter is multiplied element-wise with the corresponding input region, and the results are summed to produce a single output activation.

In transposed convolution, the process is similar but applied in reverse:

- The filter is not applied directly to the input feature map but instead used to spread its contribution to the larger output feature map.

- Each input element is multiplied by every element of the filter, and the weighted filter values are then copied into the output tensor.

- If multiple filter applications overlap at the same location in the output, their values are summed.

This effectively reconstructs a higher-resolution representation while learning spatial dependencies in an upsampling operation.

Step-by-Step Process of Transposed Convolution

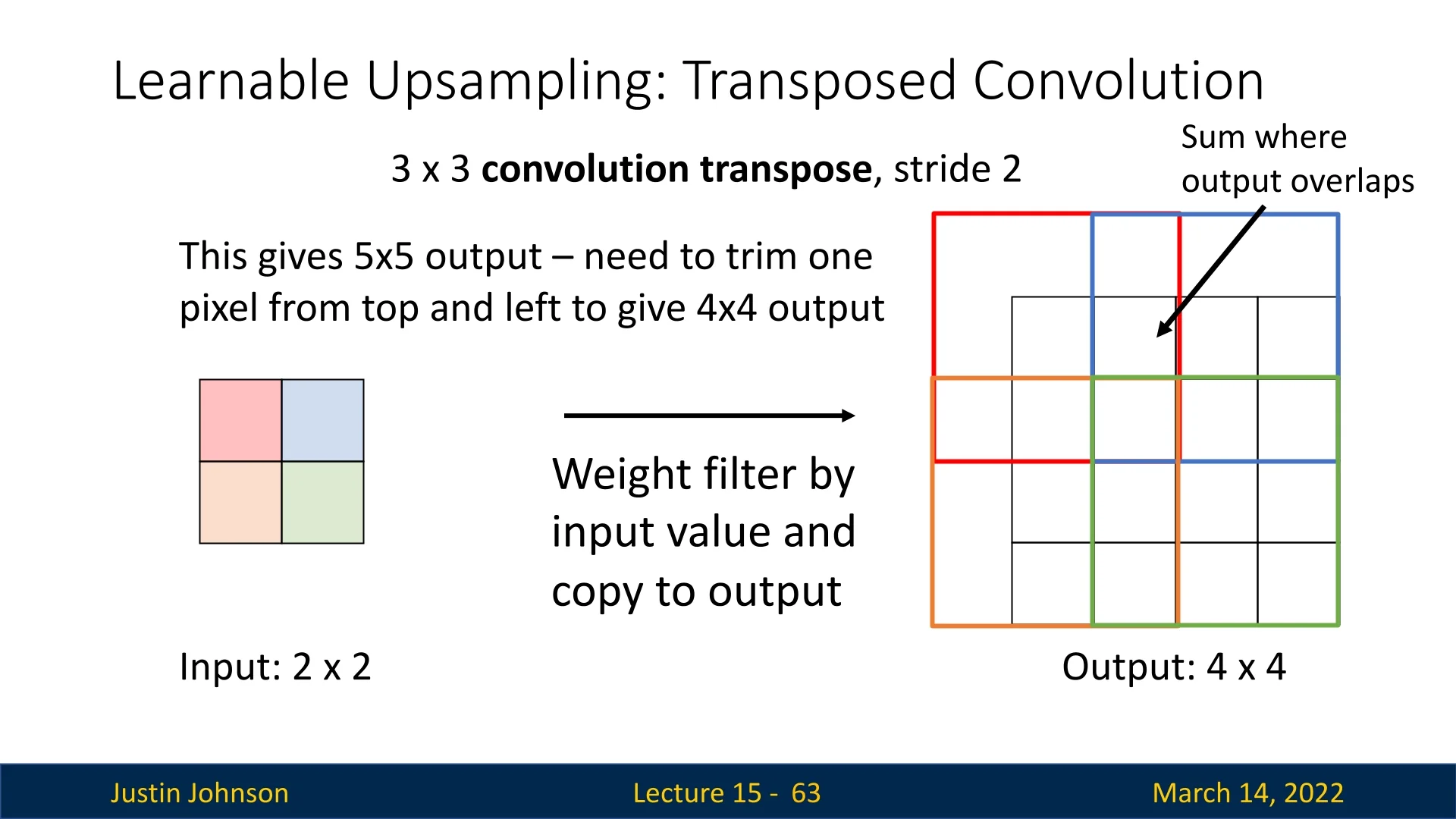

To illustrate how transposed convolution operates, consider a \(2 \times 2\) input feature map processed with a \(3 \times 3\) filter and a stride of 2, producing a \(4 \times 4\) output. The process consists of the following steps:

- 1.

- Processing the First Element:

- The first input value is multiplied element-wise with each value in the \(3 \times 3\) filter.

- The weighted filter response is then placed into its corresponding region in the output tensor, which was initially set to zeros.

- 2.

- Processing the Second Element:

- The second input element undergoes the same multiplication with the filter, producing another set of weighted values.

- These values are positioned in the output grid according to the stride of 2.

- When regions of the output overlap due to filter applications, the corresponding values are summed instead of overwritten.

- 3.

- Iterating Over the Remaining Elements:

- The process is repeated for all input elements, progressively constructing the upsampled feature map.

- The final reconstructed output is a \(4 \times 4\) feature map, demonstrating how transposed convolution expands spatial resolution while preserving learned feature relationships.

1D Transposed Convolution

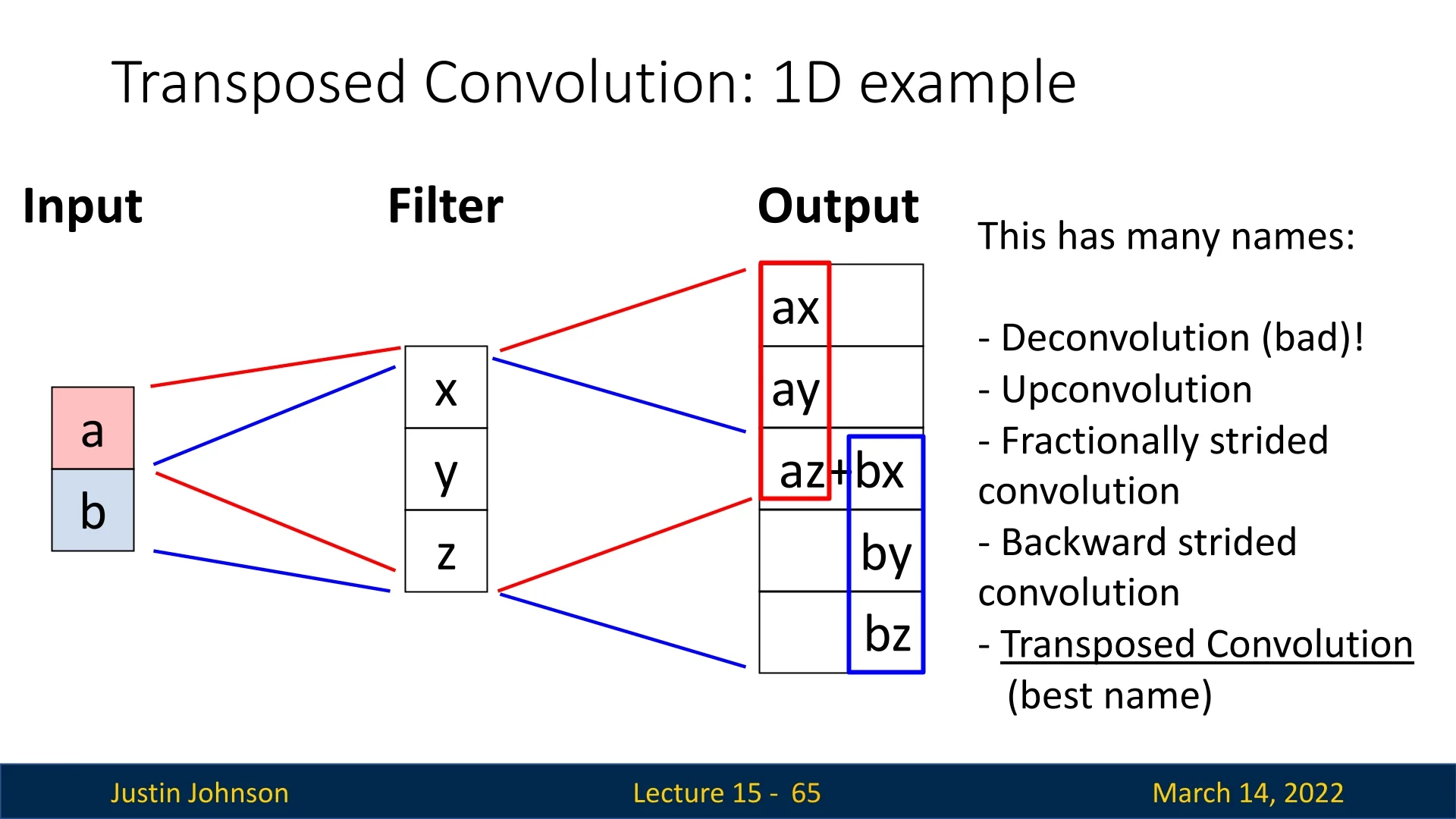

A particularly clear way to build intuition for transposed convolution is to start from a simple 1D example and view it as a “scale, place, and sum” operation. Consider a transposed convolution that maps a 2-element input to a 5-element output using a 3-element kernel with stride \(S = 2\) and no padding.

- Input: \(\mathbf {u} = [a,\, b]^\top \)

- Kernel (filter): \(\mathbf {k} = [x,\, y,\, z]^\top \)

- Output: \(\mathbf {v} \in \mathbb {R}^5\)

The forward computation can be understood in three steps:

1. Scale and place each input element For each input element, we multiply the entire kernel and place the resulting block into the output at a location determined by the stride \(S\).

- For the first input \(a\), we form \[ a \cdot [x, y, z] = [ax,\, ay,\, az], \] and place it starting at the first output position: \[ [ax,\, ay,\, az,\, 0,\, 0]. \]

- For the second input \(b\), we again form \[ b \cdot [x, y, z] = [bx,\, by,\, bz], \] but now place it shifted by the stride \(S = 2\). This means its first element aligns with the third output position: \[ [0,\, 0,\, bx,\, by,\, bz]. \]

2. Sum overlapping contributions The final output \(\mathbf {v}\) is the elementwise sum of these placed blocks: \[ \mathbf {v} = \underbrace {[ax,\, ay,\, az,\, 0,\, 0]}_{\mbox{from } a} + \underbrace {[0,\, 0,\, bx,\, by,\, bz]}_{\mbox{from } b} = [ax,\, ay,\, az + bx,\, by,\, bz]^\top . \] The third position receives contributions from both \(a\) and \(b\), illustrating how transposed convolution blends neighboring inputs via overlapping kernel footprints.

3. Why 5 output elements? Role of stride The output length is determined by the standard 1D transposed convolution formula (no padding): \[ N_{\mbox{out}} = S \cdot (N_{\mbox{in}} - 1) + K, \] where \(N_{\mbox{in}} = 2\) (input length), \(K = 3\) (kernel size), \(S = 2\) (stride). Thus, \[ N_{\mbox{out}} = 2 \cdot (2 - 1) + 3 = 5. \] Intuitively, stride \(S = 2\) means that the two kernel “footprints” are placed two positions apart in the output, and each footprint spans \(K = 3\) elements, causing them to overlap in the middle.

In higher dimensions (e.g., 2D feature maps), exactly the same mechanism applies: each activation spreads its influence over a local neighborhood, shifted according to the stride, and overlapping contributions are summed to produce a larger, learned upsampled feature map.

Why use stride \(S>1\) in transposed convolutions? In practice, choosing a stride \(S>1\) in a transposed convolution is precisely how we perform learnable upsampling in a single layer. For a transposed convolution with stride \(S\), kernel size \(K\), padding \(P\), and 1D input length \(I\), \[ O = (I - 1)\cdot S + K - 2P \] controls the output size. For example, \(S=2\) approximately doubles the spatial resolution, and \(S=4\) approximately quadruples it (up to boundary effects). This is why decoder architectures for semantic segmentation (e.g., U-Net, FCN-style models) or generators in GANs and super-resolution networks routinely use stride-2 (or larger) transposed convolutions: they efficiently map low-resolution feature maps back to higher resolutions while learning how information should be distributed into the new pixels. Implementation-wise, a stride-\(S\) transposed convolution is equivalent to inserting \(S-1\) zeros between input positions and then applying a stride-1 convolution with the same kernel, but deep learning libraries realize this without explicitly constructing the enlarged, sparse intermediate tensor.

15.3.7 Convolution and Transposed Convolution as Matrix Multiplication

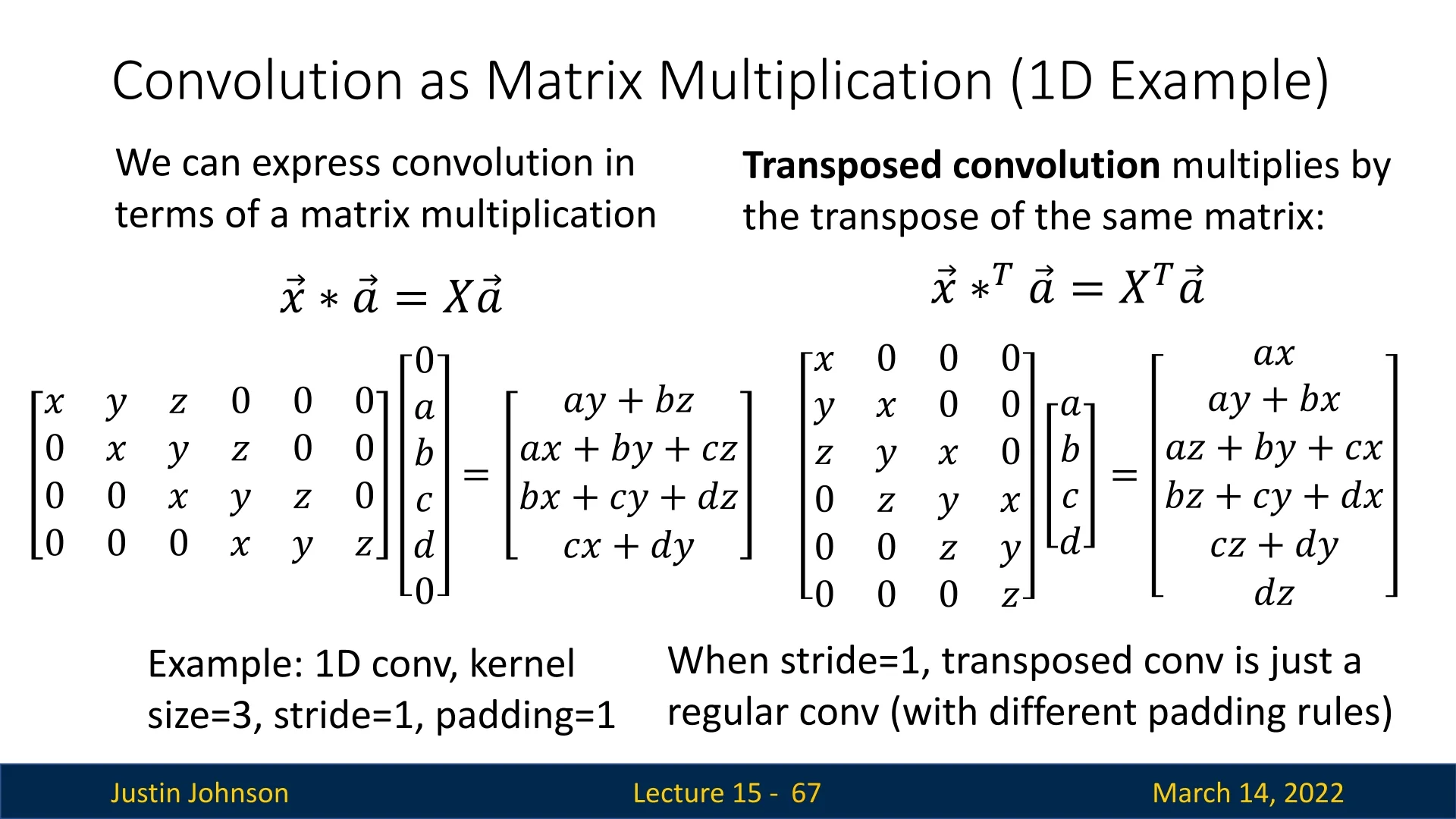

Convolutions are linear operations and can always be written as matrix–vector products. This viewpoint is useful conceptually (it shows that convolution is just a special sparse linear map) and practically (it explains why the forward pass of a transposed convolution corresponds to multiplying by the transpose of the convolution matrix, and why the backward pass of a standard convolution looks like a transposed convolution).

Standard Convolution via Matrix Multiplication

Consider a 1D convolution with stride \(S=1\) and no padding. Let

- Input: \(\mathbf {x} = [x_1, x_2, x_3, x_4]^\top \in \mathbb {R}^{4}\).

- Kernel (filter): \(\mathbf {w} = [w_1, w_2, w_3]^\top \in \mathbb {R}^{3}\).

With valid convolution, the output has length \[ O = I - K + 1 = 4 - 3 + 1 = 2, \] and its entries are \[ y_1 = w_1 x_1 + w_2 x_2 + w_3 x_3, \qquad y_2 = w_1 x_2 + w_2 x_3 + w_3 x_4. \]

We can write this as a matrix–vector product \[ \mathbf {y} = C \mathbf {x}, \] where \(C \in \mathbb {R}^{2 \times 4}\) is a Toeplitz matrix constructed from the kernel: \[ C = \begin {bmatrix} w_1 & w_2 & w_3 & 0 \\ 0 & w_1 & w_2 & w_3 \end {bmatrix}. \] Then \[ C \mathbf {x} = \begin {bmatrix} w_1 & w_2 & w_3 & 0 \\ 0 & w_1 & w_2 & w_3 \end {bmatrix} \begin {bmatrix} x_1 \\ x_2 \\ x_3 \\ x_4 \end {bmatrix} = \begin {bmatrix} w_1 x_1 + w_2 x_2 + w_3 x_3 \\ w_1 x_2 + w_2 x_3 + w_3 x_4 \end {bmatrix}, \] which matches the convolution exactly.

Each row of \(C\) encodes one position of the sliding kernel:

- Row 1 aligns \([w_1, w_2, w_3]\) with \([x_1, x_2, x_3]\).

- Row 2 shifts this pattern one step to the right, aligning with \([x_2, x_3, x_4]\).

Positions that would fall outside the input are filled with zeros. In higher dimensions (2D images, 3D volumes) and with multiple channels, the same idea produces larger, block-structured Toeplitz matrices.

Stride \(S>1\) in standard convolution For stride \(S>1\), the convolution still has the form \(\mathbf {y} = C_S \mathbf {x}\) for a suitable sparse matrix \(C_S\). Intuitively, the kernel still slides along the input, but we only keep every \(S\)-th output. In matrix form, this corresponds either to:

- Taking a subset of rows from the stride-1 Toeplitz matrix.

- Directly constructing a sparser matrix \(C_S\) whose rows correspond to windows starting at positions \[ 1,\; 1 + S,\; 1 + 2S,\; \dots \] in the input.

Transposed Convolution as the Matrix Transpose

The transposed convolution associated with a given (discrete) convolution is most cleanly defined via the transpose of its convolution matrix. If a standard 1D convolution with stride \(S\) can be written as \[ \mathbf {y} = C_S \mathbf {x}, \] then its associated transposed convolution is the linear map \[ \mathbf {x}' = C_S^\top \mathbf {y}. \] When \(C_S\) corresponds to a downsampling convolution (e.g., \(S > 1\)), this adjoint map typically increases spatial extent, which is why transposed convolutions are used for upsampling.

For the stride-\(1\) example above, the convolution matrix is \[ C = \begin {bmatrix} w_1 & w_2 & w_3 & 0 \\ 0 & w_1 & w_2 & w_3 \end {bmatrix} \in \mathbb {R}^{2 \times 4}, \] so its transpose is \[ C^\top = \begin {bmatrix} w_1 & 0 \\ w_2 & w_1 \\ w_3 & w_2 \\ 0 & w_3 \end {bmatrix} \in \mathbb {R}^{4 \times 2}. \] Given \(\mathbf {y} = [y_1, y_2]^\top \), the transposed convolution computes \[ \mathbf {x}' = C^\top \mathbf {y} = \begin {bmatrix} w_1 y_1 \\ w_2 y_1 + w_1 y_2 \\ w_3 y_1 + w_2 y_2 \\ w_3 y_2 \end {bmatrix}. \] Each element of \(\mathbf {y}\) is “spread” over three positions in \(\mathbf {x}'\), weighted by the kernel, and overlapping contributions are summed. For \(S=1\), both \(C\) and \(C^\top \) are Toeplitz matrices, so the adjoint is itself a normal convolution (with a flipped kernel).

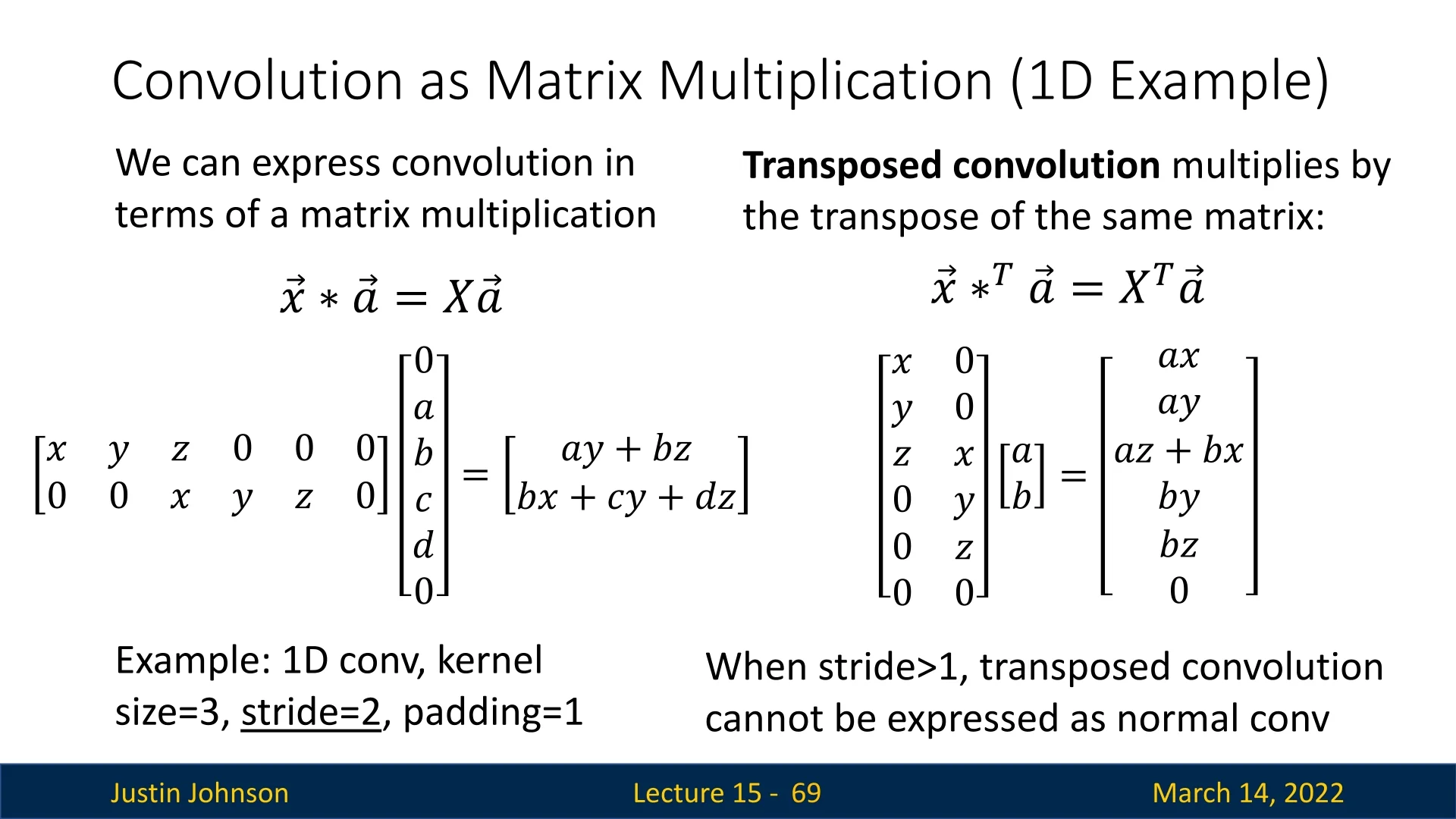

Relating to the \([a, b]^\top \) and \([x, y, z]^\top \) Example (Stride \(S=2\))

We now connect the intuitive scale–place–sum example to the matrix view for stride \(S=2\). Consider a standard 1D convolution with:

- Input: \(\mathbf {v} = [v_1, v_2, v_3, v_4, v_5]^\top \).

- Kernel: \(\mathbf {k} = [x, y, z]^\top \).

- Stride: \(S = 2\), no padding.

The output \(\mathbf {u} = [u_1, u_2]^\top \) is \[ u_1 = x v_1 + y v_2 + z v_3, \qquad u_2 = x v_3 + y v_4 + z v_5, \] so the convolution matrix \(W \in \mathbb {R}^{2 \times 5}\) is \[ W = \begin {bmatrix} x & y & z & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & x & y & z \end {bmatrix}. \] Each row corresponds to placing the kernel at positions \((1,2,3)\) and \((3,4,5)\) in the input, reflecting the stride \(S=2\).

The associated transposed convolution uses \(W^\top \): \[ W^\top = \begin {bmatrix} x & 0 \\ y & 0 \\ z & x \\ 0 & y \\ 0 & z \end {bmatrix} \in \mathbb {R}^{5 \times 2}. \] Given a 2-element input \(\mathbf {u} = [a, b]^\top \), the transposed convolution computes \[ \mathbf {v}' = W^\top \mathbf {u} = a \begin {bmatrix} x \\ y \\ z \\ 0 \\ 0 \end {bmatrix} + b \begin {bmatrix} 0 \\ 0 \\ x \\ y \\ z \end {bmatrix} = \begin {bmatrix} ax \\ ay \\ az + bx \\ by \\ bz \end {bmatrix}. \] Thus the mapping \[ [a, b]^\top \;\xrightarrow {\;\mbox{kernel }[x,y,z]^\top ,\; S=2\;} [ax,\, ay,\, az+bx,\, by,\, bz]^\top \] is exactly the same 1D transposed convolution we described earlier, now written as a single matrix–vector product \(\mathbf {v}' = W^\top \mathbf {u}\).

Strides, Upsampling, and the “Normal Convolution” Caveat

The matrix viewpoint is completely general: for any stride \(S\), both convolution and its adjoint remain linear maps and can always be written as \[ \mathbf {y} = C_S \mathbf {x}, \qquad \mathbf {x}' = C_S^\top \mathbf {y}, \] for some (possibly large and sparse) matrix \(C_S\). This makes it clear that:

- The operations are differentiable everywhere, with Jacobians given by \(C_S\) and \(C_S^\top \).

- Gradients with respect to inputs and kernels are just matrix–vector products involving these matrices or their transposes.

However, there is an important subtlety when \(S>1\):

- For \(\boldsymbol {S=1}\), the convolution matrix \(C\) is Toeplitz, and its transpose \(C^\top \) is also Toeplitz. In this case, both the forward convolution \(\mathbf {y} = C \mathbf {x}\) and the adjoint \(\mathbf {x}' = C^\top \mathbf {y}\) are normal convolutions on the same grid, with different (flipped) kernels.

- For \(\boldsymbol {S>1}\), the forward convolution matrix \(C_S\) is still Toeplitz (up to zero rows corresponding to skipped positions), but its transpose \(C_S^\top \) is no longer Toeplitz. As the stride example above shows, \(W^\top \) does not have constant diagonals, so there is no single kernel and stride configuration that realizes \(\mathbf {x}' = C_S^\top \mathbf {y}\) as a single standard convolution on the original input grid.

This is precisely the sense in which, for \(S>1\), a transposed convolution cannot be expressed as a normal convolution acting directly on \(\mathbf {y}\): its matrix is not a convolution (Toeplitz) matrix on that grid. Instead, the usual implementation factorizes the operation into two steps:

- 1.

- Zero-insertion (upsampling). Conceptually insert \(S-1\) zeros between consecutive elements of \(\mathbf {y}\), creating an enlarged, sparse feature map.

- 2.

- Stride-1 convolution. Apply a normal stride-1 convolution (with an appropriate kernel) to this upsampled signal.

On the upsampled grid, the second step is again a standard convolution with a Toeplitz matrix. But on the original grid, the full operator is no longer a single convolution; it is the composition of upsampling (a fixed linear map) and a stride-1 convolution. Deep learning libraries implement transposed convolutions in exactly this way for efficiency, rather than explicitly forming \(C_S^\top \).

In summary:

- Mathematically, for any stride \(S\), convolution and transposed convolution are linear maps with an adjoint relationship \(\mathbf {y} = C_S \mathbf {x}\), \(\mathbf {x}' = C_S^\top \mathbf {y}\).

- For \(S=1\), both maps are themselves normal convolutions on the same grid.

- For \(S>1\), the adjoint \(C_S^\top \) is not a normal convolution on the original grid, but can be implemented as “upsample (insert zeros) + stride-1 convolution” on a finer grid.

This clarifies why transposed convolutions with stride \(S>1\) are treated as a distinct primitive in modern libraries, even though they are still fully linear and differentiable and remain the exact adjoints of their corresponding strided convolutions.

Advantages of Transposed Convolution

Relative to fixed upsampling operations such as bilinear interpolation or max unpooling, transposed convolution offers several advantages:

- Learnable weights: The kernel parameters are trained end-to-end, allowing the network to learn how best to interpolate and refine details for the specific task.

- Trainable spatial structure: Because it is a convolution, the operation naturally captures local spatial patterns and can reconstruct sharp edges and meaningful structures rather than merely smoothing.

- Flexible stride and padding: As with standard convolutions, stride, kernel size, and padding provide fine-grained control over the output resolution, making it easy to design multi-scale encoder–decoder architectures.

Challenges and Considerations

While transposed convolution is highly effective, it introduces some challenges:

- Checkerboard Artifacts: Overlapping filter applications can create unevenly distributed activations, leading to artifacts in the output.

- Sensitivity to Stride and Padding: Incorrect configurations can lead to distorted feature maps or excessive upsampling.

15.3.8 Conclusion: Choosing the Right Upsampling Method

In this chapter we examined several upsampling and unpooling strategies, ranging from simple, non-learnable schemes to fully learnable transposed convolutions. Each method makes a different trade-off between computational cost, spatial faithfulness, smoothness, and the ability to recover or hallucinate fine details. In practice, the “right” choice depends on the task (e.g., semantic segmentation vs. super-resolution), the downsampling operations used in the encoder (max pooling vs. strided convolutions), and the amount of computation and complexity you are willing to invest in the decoder.

| Upsampling Method | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|

| Nearest-Neighbor Unpooling / Upsampling | Extremely simple and fast; no learnable parameters; preserves exact values of input pixels or features | Produces blocky, jagged artifacts; no notion of continuity; cannot reconstruct fine details or smooth transitions. |

| Bed of Nails Unpooling | Simple non-learnable unpooling; preserves original values in fixed locations; keeps sparsity structure | Places activations in arbitrary fixed positions (e.g., always top-left); breaks spatial alignment with the encoder; creates unnatural gaps and aliasing; generally inferior to max unpooling. |

| Bilinear Interpolation | Fast, differentiable, and easy to implement; produces smooth transitions and avoids blocky artifacts | Averages over local neighborhoods, which blurs edges and textures; cannot recover high-frequency details lost during downsampling. |

| Bicubic Interpolation | Uses a larger neighborhood and cubic weights; typically sharper outputs and better detail preservation than bilinear | More computationally expensive; still non-learnable and can introduce mild blurring or ringing near sharp boundaries. |

| Max Unpooling | Restores activations to their exact locations recorded by max pooling; preserves spatial layout of salient features and encoder–decoder alignment | Produces sparse feature maps (zeros in non-max positions) that require subsequent convolutions for refinement; only applicable when pooling indices are available. |

| Transposed Convolution | Fully learnable upsampling; can reconstruct or hallucinate high-frequency structure; flexible control of output size through kernel, stride, and padding | Higher computational cost; can introduce checkerboard artifacts if kernel size, stride, and padding are poorly chosen; more sensitive to implementation details. |

Guidelines for Choosing an Upsampling Method

The upsampling strategy should be chosen in concert with the encoder design and the target task. The following guidelines capture common patterns used in practice:

-

Match the encoder’s downsampling when using max pooling.

When the encoder uses max pooling, max unpooling is a natural counterpart: it reuses the recorded pooling indices to place activations back into their original spatial locations. This preserves spatial correspondence between encoder and decoder feature maps.Because the unpooled output is sparse, it should almost always be followed by one or more convolutional layers to “densify” and refine the feature map. In contrast, Bed of Nails unpooling does not respect the original pooling geometry and typically leads to misaligned features and artifacts, so it is best viewed as a simple didactic baseline rather than a practical choice.

- Use interpolation when you want smooth, non-learnable

upsampling.

For tasks where smoothness and simplicity are more important than exact detail reconstruction (or when a lightweight baseline is sufficient), bilinear interpolation is a robust default. It avoids blocky artifacts and is inexpensive. Bicubic interpolation is preferred when additional sharpness is desired and the extra cost is acceptable. In both cases, the upsampled features are often followed by a standard convolution layer to reintroduce some learnable flexibility. - Combine simple upsampling with convolution to avoid

artifacts.

A widely used pattern in modern architectures is: resize (nearest-neighbor or bilinear) \(\rightarrow \) convolution. The interpolation step handles the geometric upsampling, while the subsequent convolution learns to refine and reweight the features. This decoupled design avoids checkerboard artifacts associated with poorly configured transposed convolutions, yet retains learnable capacity through the convolutional layer. - Use transposed convolution when learnable upsampling is

essential.

Transposed convolutions are often preferred in semantic segmentation decoders, autoencoders, super-resolution networks, and GAN generators, where the decoder must learn how to reconstruct or hallucinate fine details from compact representations. By choosing appropriate kernel sizes and strides (e.g., even kernel sizes and strides that match the encoder’s downsampling pattern), transposed convolutions can provide powerful, learnable upsampling. Careful design or additional smoothing (e.g., a small convolution after the transposed convolution) is recommended to mitigate checkerboard artifacts. - For encoders without explicit pooling, favor learned,

structured upsampling.

In fully convolutional architectures that rely primarily on strided convolutions for downsampling, there are no pooling indices to reuse. In such cases, transposed convolutions or interpolation + convolution blocks provide a natural way to invert the spatial contraction, since they can be configured to mirror the encoder’s stride pattern and learn how to reconstruct structured high-resolution outputs.

In summary, nearest-neighbor and Bed of Nails unpooling serve as simple baselines, interpolation methods provide smooth but non-learnable upsampling, and max unpooling plus transposed convolutions exploit encoder information or learnable filters to recover structure. Most practical decoders combine these ideas—using indices when available, interpolation when stability and simplicity matter, and learnable convolutions when detailed reconstruction is crucial.

15.5 Instance Segmentation

Instance segmentation is a critical task in computer vision that aims to simultaneously detect and delineate each object instance within an image. Unlike semantic segmentation, which assigns a class label to each pixel without distinguishing between different object instances of the same category, instance segmentation uniquely identifies each occurrence of an object. This is particularly important for applications where individual object identification is required, such as autonomous driving, medical imaging, and robotics.

In computer vision research, image regions are categorized into two types: things and stuff. This distinction is fundamental to instance segmentation, where individual object instances are identified at the pixel level.

- Things: Object categories that can be distinctly separated into individual instances, such as cars, people, and animals.

- Stuff: Object categories that lack clear instance boundaries, such as sky, grass, water, and road surfaces.

Instance segmentation focuses exclusively on things, as segmenting instances of stuff is not meaningful. The primary goal of instance segmentation is to detect all objects in an image and assign a unique segmentation mask to each detected object, ensuring correct differentiation of overlapping instances.

This task is particularly challenging due to the need for accurate pixel-wise delineation while simultaneously handling object occlusions, varying scales, and complex background clutter. Advanced deep learning architectures, such as Mask R-CNN, have significantly improved the performance of instance segmentation by leveraging region-based feature extraction and mask prediction techniques.

The development of instance segmentation models continues to evolve, driven by the increasing demand for high-precision vision systems across various domains.

15.4.1 Mask R-CNN: A Two-Stage Framework for Instance Segmentation

Mask R-CNN extends Faster R-CNN, a widely used two-stage object detection framework, by incorporating a dedicated branch for per-instance segmentation masks. While Faster R-CNN predicts bounding boxes and class labels, Mask R-CNN further refines this process by generating high-resolution segmentation masks for each detected object.

Faster R-CNN Backbone

Faster R-CNN builds on a convolutional backbone (e.g., ResNet with or without FPN) that extracts a shared feature map for the entire image. On top of these features, a Region Proposal Network (RPN) predicts a set of candidate object bounding boxes (region proposals) together with objectness scores. For each proposal, features are cropped from the shared feature map (via RoI pooling or RoI Align) and passed through two parallel heads: a classification head that predicts the object category via softmax, and a bounding box regression head that refines the proposal coordinates via regression. This two-stage design yields class-labeled, refined bounding boxes and serves as the foundation for Mask R-CNN.

Key Additions in Mask R-CNN

Mask R-CNN preserves the overall Faster R-CNN structure while introducing two key modifications that enable instance-level segmentation:

-

A mask prediction head. A lightweight fully convolutional network (FCN) branch predicts a binary segmentation mask for each detected object instance. Instead of producing a single segmentation map for the whole image, Mask R-CNN outputs one mask per region of interest (RoI). The mask head consists of several convolutional layers followed by a deconvolution (transposed convolution) layer that upsamples RoI features (e.g., from \(14 \times 14\) to \(28 \times 28\)) before a final \(1 \times 1\) convolution produces per-pixel mask logits. The weights of this head are learned jointly with the detection heads.

- RoI Align for precise feature extraction. Faster R-CNN originally used RoI Pooling, which quantizes RoI coordinates to discrete bins and introduces misalignment between the RoI and the underlying feature map. Mask R-CNN replaces this with RoI Align, which avoids any rounding and uses bilinear interpolation to sample feature values at exact (possibly fractional) locations. This improves alignment, especially for small objects, and is crucial for accurate mask boundaries.

As a result, the second stage of Mask R-CNN produces three parallel outputs for each region proposal:

- Class label, predicted via a softmax classification head.

- Bounding box refinement, predicted by a regression head that outputs coordinate offsets.

- Segmentation mask, predicted by the FCN-based mask branch.

Segmentation Mask Prediction: Fixed-Size Output

A central challenge in instance segmentation is handling objects of widely varying sizes while keeping computation manageable. Mask R-CNN addresses this by predicting a fixed-size mask for each RoI and then resizing it to the object’s bounding box in the original image.

Concretely, for each positive RoI:

- 1.

- The RPN generates region proposals on top of the backbone feature map.

- 2.

- The classification and bounding box regression heads operate on RoI-aligned features to predict the object category and refine the bounding box coordinates.

- 3.

- In parallel, the mask head takes the same RoI-aligned features and outputs a tensor of shape \(C \times 28 \times 28\), where \(C\) is the number of object classes. Each channel corresponds to a class-specific mask prediction at a fixed spatial resolution.

- 4.

- During inference, the mask corresponding to the predicted class for that RoI is selected, yielding a single \(28 \times 28\) mask for that instance.

- 5.

- This selected \(28 \times 28\) mask is then resized to the spatial extent of the refined bounding box using bilinear interpolation and placed at the appropriate location in the original image coordinate system.

In other words, the transposed convolution inside the mask head learns to produce a relatively high-resolution, fixed-size mask in feature space, while a final bilinear interpolation step adapts this fixed-size mask to the object’s actual size in the input image.

Training Mask R-CNN and Loss Functions

Mask R-CNN is trained end-to-end as a multi-task model, jointly optimizing detection (classification and bounding boxes) and segmentation. The training objective is the sum of three losses:

- Classification loss \(L_{cls}\). A standard softmax cross-entropy loss applied to the classification head to encourage correct object category predictions for each RoI.

- Bounding box regression loss \(L_{box}\). A smooth L1 loss applied to the predicted bounding box offsets for positive RoIs (those that sufficiently overlap a ground-truth object), improving localization accuracy.

- Mask loss \(L_{mask}\). A per-pixel binary cross-entropy loss applied to the mask prediction branch. For each positive RoI, this loss is computed only on the channel corresponding to the ground-truth class, ignoring all other class channels. This class-specific loss encourages accurate foreground–background separation and precise object boundaries.

The total loss is given by \[ L = L_{cls} + L_{box} + L_{mask}, \] where:

- \(L_{cls}\) is the classification loss.

- \(L_{box}\) is the bounding box regression loss.

- \(L_{mask}\) is the mask prediction loss.

In practice, the backbone network (e.g., ResNet with or without FPN) is first pretrained on a large-scale image classification dataset such as ImageNet and then fine-tuned on an instance segmentation dataset such as COCO. During fine-tuning, gradients from all three heads (classification, box regression, and mask prediction) are backpropagated through the shared backbone and RPN. This joint optimization improves both detection (bounding box mAP) and segmentation (mask mAP), and the RoI Align plus mask head design enables accurate, high-resolution instance masks while reusing the mature Faster R-CNN detection pipeline.

Bilinear Interpolation vs. Bicubic Interpolation

The upsampling step in Mask R-CNN requires resizing segmentation masks to fit detected object regions. The authors chose bilinear interpolation over bicubic interpolation for the following reasons:

- Efficiency: Bilinear interpolation is computationally less expensive than bicubic interpolation, making it suitable for processing multiple objects per image.

- Minimal Accuracy Gains from Bicubic: Bicubic interpolation considers 16 neighboring pixels, while bilinear uses only 4. Given that Mask R-CNN’s masks are already low resolution (\(28 \times 28\)), bicubic interpolation does not provide significant accuracy improvements.

- Edge Preservation: Bicubic interpolation introduces additional smoothing, which can blur object boundaries. Bilinear interpolation maintains sharper mask edges, improving segmentation performance.

Class-Aware Mask Selection

Unlike traditional multi-class segmentation models, which predict a single mask covering all categories, Mask R-CNN follows a per-instance, per-class approach:

- The segmentation head predicts C binary masks per object, where \(C\) is the number of possible classes.

- The classification head determines the object’s category.

- The corresponding mask for the predicted category is selected and applied to the object.

This method decouples classification from segmentation, preventing class competition within the mask and improving segmentation accuracy.

Gradient Flow in Mask R-CNN

Mask R-CNN’s forward pass for mask prediction closely mirrors the backward pass of standard convolutional networks. Gradient computations are structured as follows:

- The classification and bounding box losses propagate through the detection pipeline, refining object proposals.

- The segmentation loss propagates gradients through the mask prediction branch, optimizing instance masks.

- RoI Align ensures spatial alignment, preventing gradient misalignment and improving mask accuracy.

Expressing these processes as matrix–vector operations clarifies how gradients flow through the network, aiding optimization and efficient deep learning framework implementation.

Summary

Mask R-CNN extends Faster R-CNN by introducing a per-region mask prediction branch and RoI Align for accurate feature extraction. The segmentation head predicts a fixed-size \(28 \times 28\) binary mask per object, which is then resized using bilinear interpolation. This approach allows for accurate instance segmentation while maintaining computational efficiency, making Mask R-CNN a dominant framework in object segmentation applications.

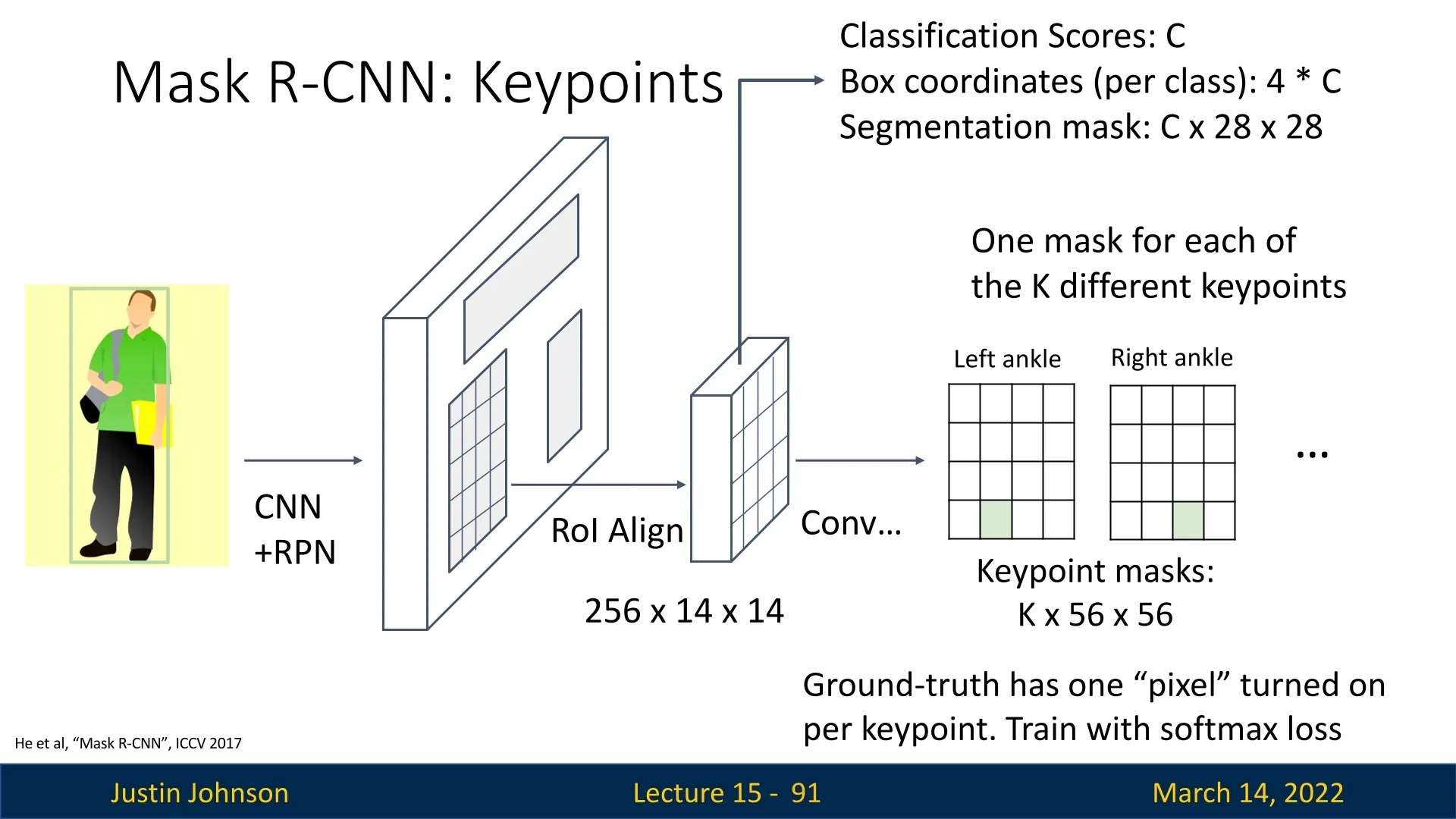

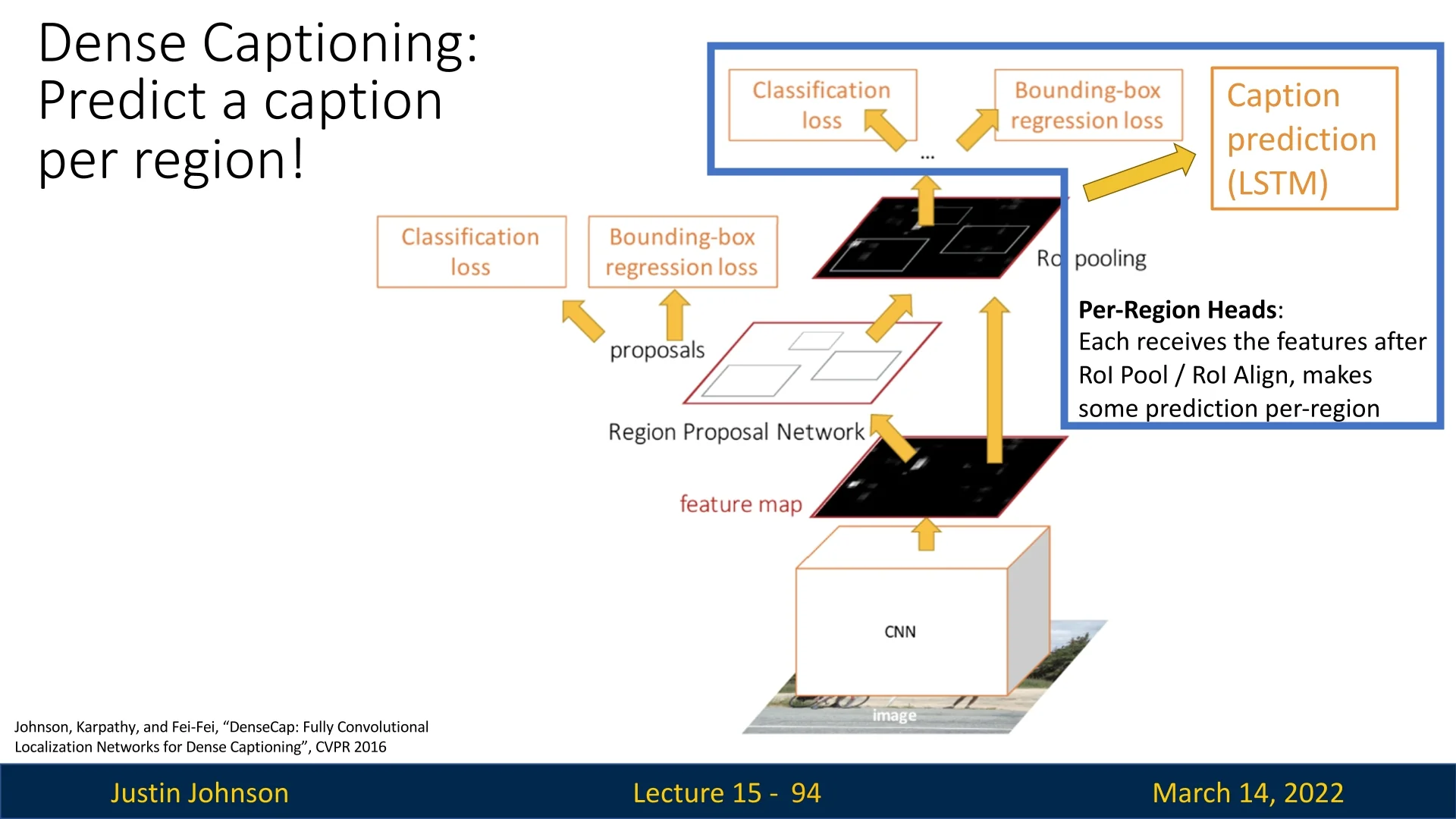

15.4.2 Extending the Object Detection Paradigm

Mask R-CNN introduced a paradigm in which object detection models can be extended to perform new vision tasks by adding task-specific prediction heads. This flexible approach has led to the development of new capabilities beyond instance segmentation, such as:

-

Keypoint Estimation: Mask R-CNN was further extended for human pose estimation by adding a keypoint detection head. This variation, sometimes called Mask R-CNN: Keypoints, predicts key locations such as joints in the human body, facilitating pose estimation.

Figure 15.17: Mask R-CNN extended for keypoint estimation, predicting key locations such as joints for human pose estimation. -

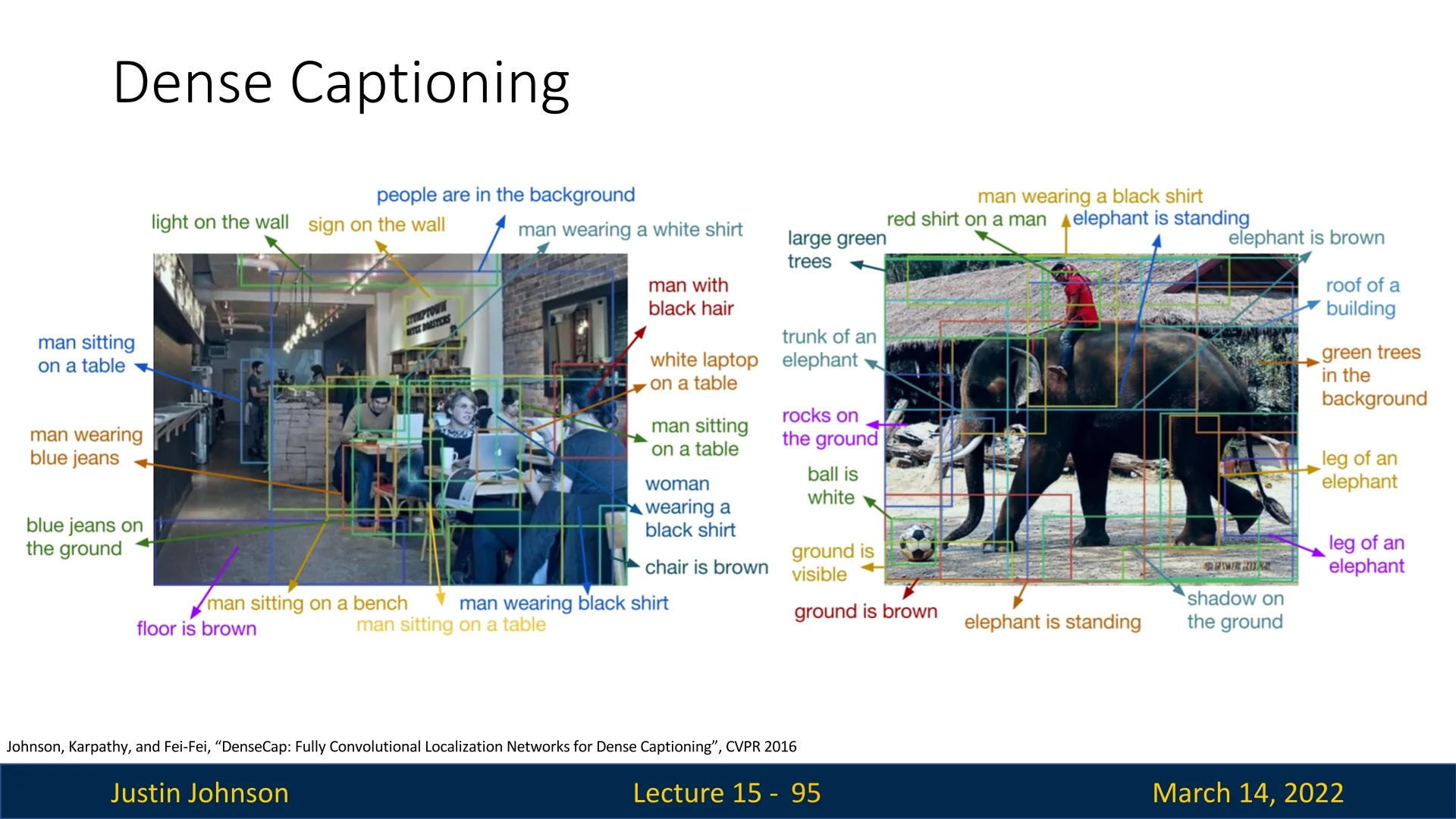

Dense Captioning: Inspired by the Mask R-CNN paradigm, DenseCap [269] extends object detection by incorporating a captioning head. This approach, illustrated below, uses an LSTM-based captioning module to describe detected regions with natural language. We’ll cover this topic in depth later on.

Figure 15.18: Dense Captioning (DenseCap) extends object detection by adding a captioning head, enabling textual descriptions of detected objects.

Figure 15.19: Example output of DenseCap: Generated captions describe detected regions with natural language. -

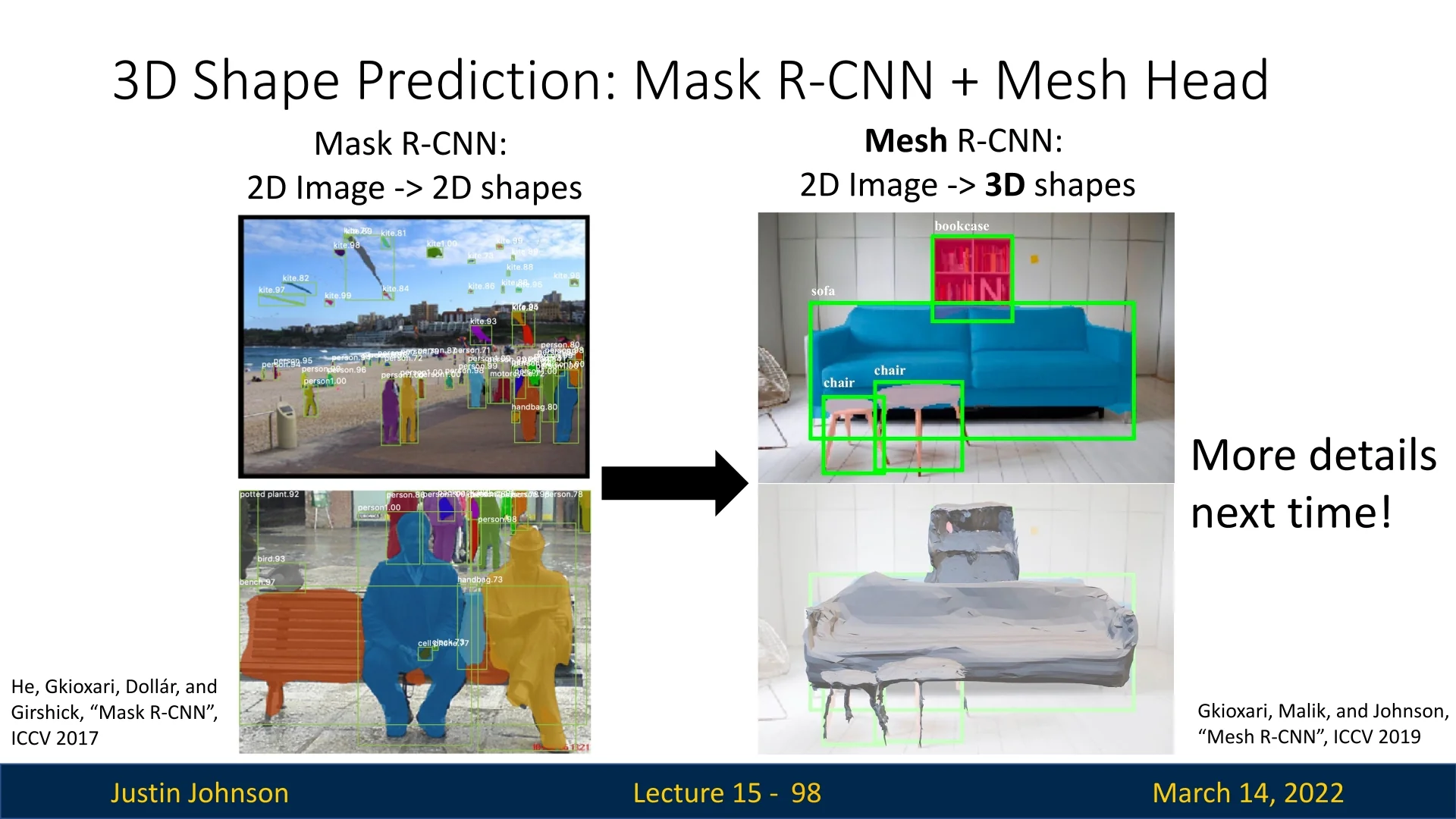

3D Shape Prediction: Mesh R-CNN [177] builds upon Mask R-CNN to predict 3D object shapes from 2D images by adding a mesh prediction head. This enables the reconstruction of 3D object geometry directly from image-based inputs, representing a significant step toward vision-based 3D reasoning.

Figure 15.20: Mesh R-CNN extends Mask R-CNN with a mesh prediction head, enabling 3D shape reconstruction from 2D images.

These extensions highlight the versatility of the Mask R-CNN framework and demonstrate how object detection networks can serve as a foundation for diverse computer vision tasks. By incorporating additional task-specific heads, researchers continue to expand the boundaries of what can be achieved using a common underlying object detection architecture. We’ll touch these ideas later on as well.

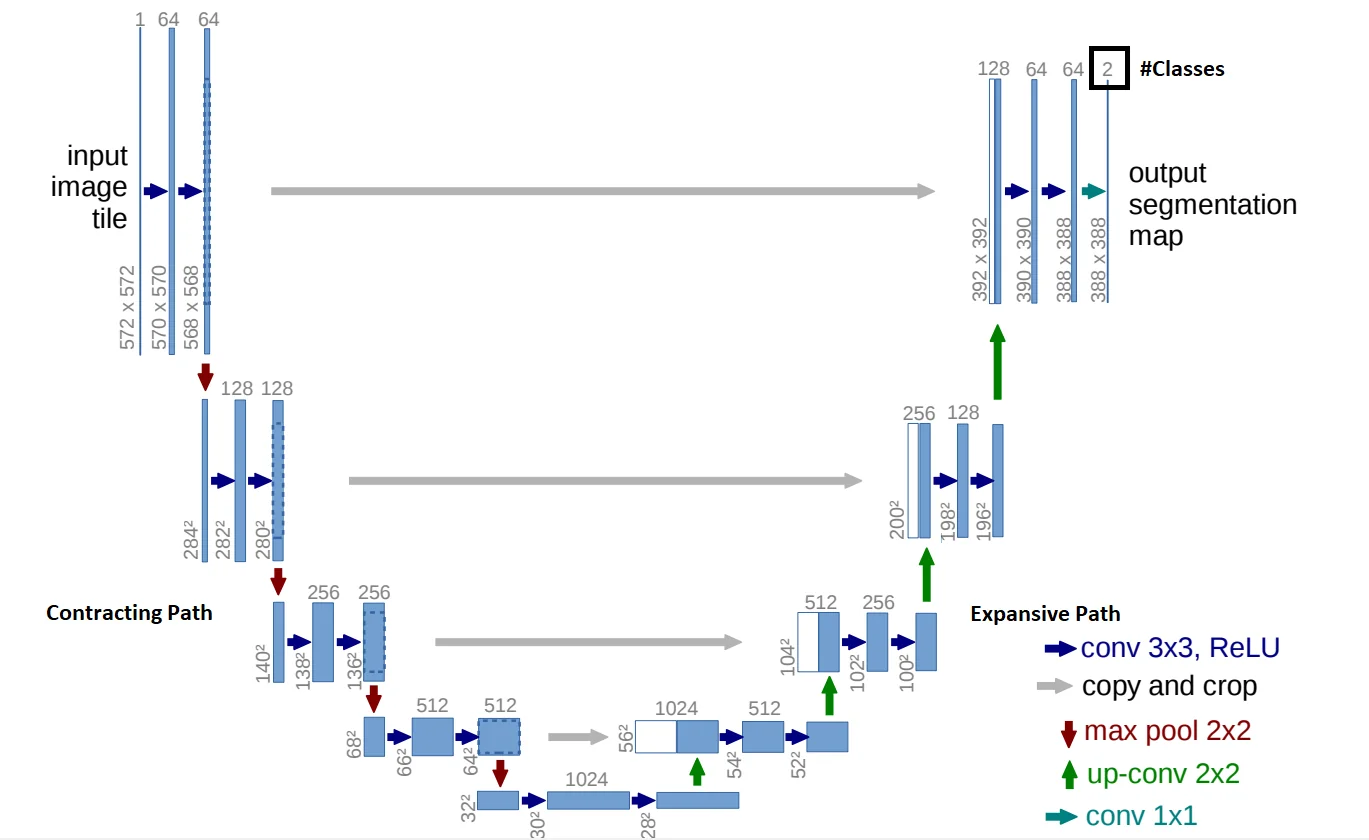

Enrichment 15.6: U-Net: A Fully Conv Architecture for Segmentation

Enrichment 15.6.1: Overview

U-Net [532] is a fully convolutional neural network designed for semantic segmentation, particularly in biomedical imaging. Unlike traditional classification networks, U-Net assigns a class label to each pixel, performing dense prediction. The architecture follows a symmetrical encoder-decoder structure, resembling a ”U” shape. The encoder (contracting path) captures contextual information, while the decoder (expansive path) refines localization details.

Enrichment 15.6.2: U-Net Architecture

U-Net consists of two key components:

-

Contracting Path (Encoder):

- Repeated \(3 \times 3\) convolutions followed by ReLU activations.

- \(2 \times 2\) max-pooling for downsampling, reducing spatial resolution while increasing feature depth.

- Captures high-level semantic information necessary for object recognition.

-

Expansive Path (Decoder):

- Transposed convolutions for upsampling, restoring spatial resolution.

- Skip connections integrate feature maps from the encoder to retain spatial details lost during downsampling.

- A \(1 \times 1\) convolution maps feature channels to the segmentation classes.

Enrichment 15.6.3: Skip Connections and Concatenation

Skip connections are a key innovation in U-Net that directly link corresponding encoder and decoder layers through concatenation. This mechanism enables:

-

Preserving Spatial Information:

- Encoder feature maps are concatenated with decoder feature maps at corresponding levels.

- This ensures that fine-grained details lost due to downsampling are reinstated.

-

Combining Semantic and Spatial Features:

- The encoder extracts abstract, high-level semantic features.

- The decoder restores fine details, and concatenation helps merge these representations.

-

Enhancing Gradient Flow During Training:

- Skip connections allow gradients to propagate more easily through deep networks, preventing vanishing gradients.

- This improves convergence and stabilizes the training process.

The concatenation operation is crucial, as it ensures that both low-level spatial features and high-level semantic features contribute to final pixel-wise classification.

Enrichment 15.6.4: Training U-Net

U-Net is trained end-to-end in a supervised manner, typically using:

-

Loss Function:

- The standard loss function for U-Net is Binary Cross-Entropy (BCE) for binary segmentation tasks.

- For multi-class segmentation, Categorical Cross-Entropy is used.

- When dealing with imbalanced datasets, Dice Loss or a combination of BCE and Dice Loss is applied.

-

Optimization:

- U-Net is typically trained using Adam or Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD) with momentum.

-

Data Augmentation:

-

Given the limited availability of annotated medical data, U-Net heavily relies on augmentation techniques such as:

- Random rotations, flips, and intensity shifts.

- Elastic deformations to improve robustness.

-

The combination of skip connections, effective loss functions, and augmentation techniques ensures that U-Net achieves high accuracy even with limited training data.

Enrichment 15.6.5: Comparison with Mask R-CNN

While both U-Net and Mask R-CNN perform segmentation, they differ in:

- Task Type: U-Net performs semantic segmentation; Mask R-CNN performs instance segmentation.

- Architecture: U-Net follows an encoder-decoder design, while Mask R-CNN uses a two-stage detection-segmentation approach.

- Application Domains: U-Net is dominant in medical imaging and satellite imagery, whereas Mask R-CNN excels in object detection and video analytics.

Enrichment 15.6.6: Impact and Evolution of U-Net

Since its introduction, U-Net has significantly influenced segmentation research, inspiring numerous adaptations and improvements:

- U-Net++ [802]: Incorporates dense connections between encoder-decoder layers to improve gradient flow and feature reuse.

- 3D U-Net [106]: Extends the architecture to volumetric data, benefiting applications like MRI and CT scan analysis.

- Residual U-Net [784]: Integrates residual blocks to enhance gradient flow and stabilize training for deeper architectures.

- Hybrid U-Net Variants: Many modern adaptations replace the convolutional backbone with newer architectures, such as vision transformers, to enhance feature extraction.

Although Attention U-Net [457] introduces an attention mechanism to selectively focus on relevant features, we have not yet covered attention mechanisms in this course. However, the core U-Net structure remains effective even without attention mechanisms and is widely used in practice. With continuous enhancements, U-Net’s impact on segmentation research persists across various domains.

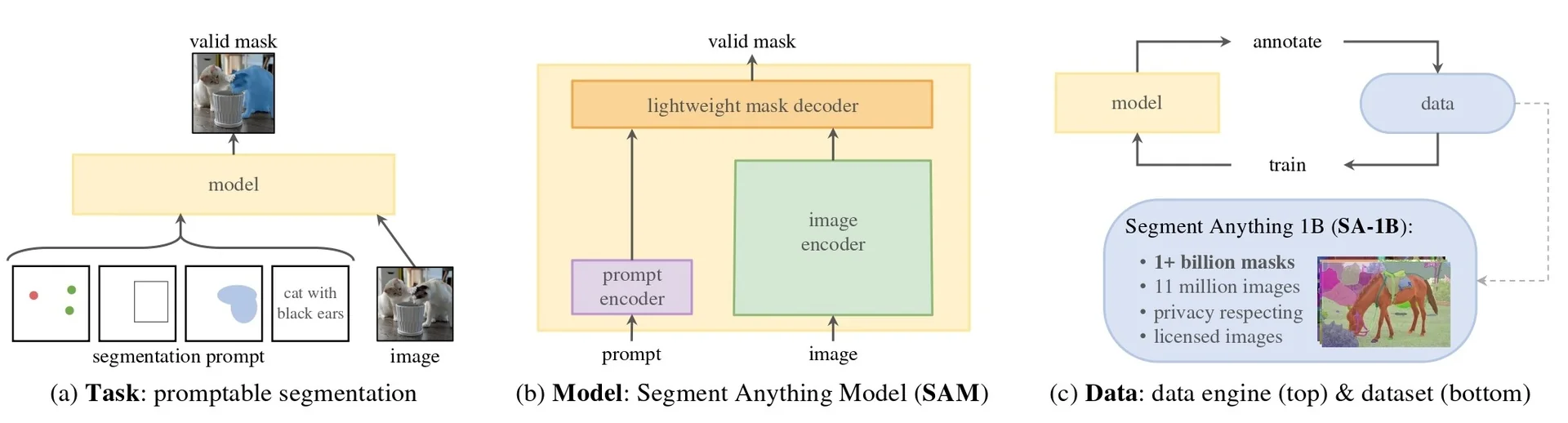

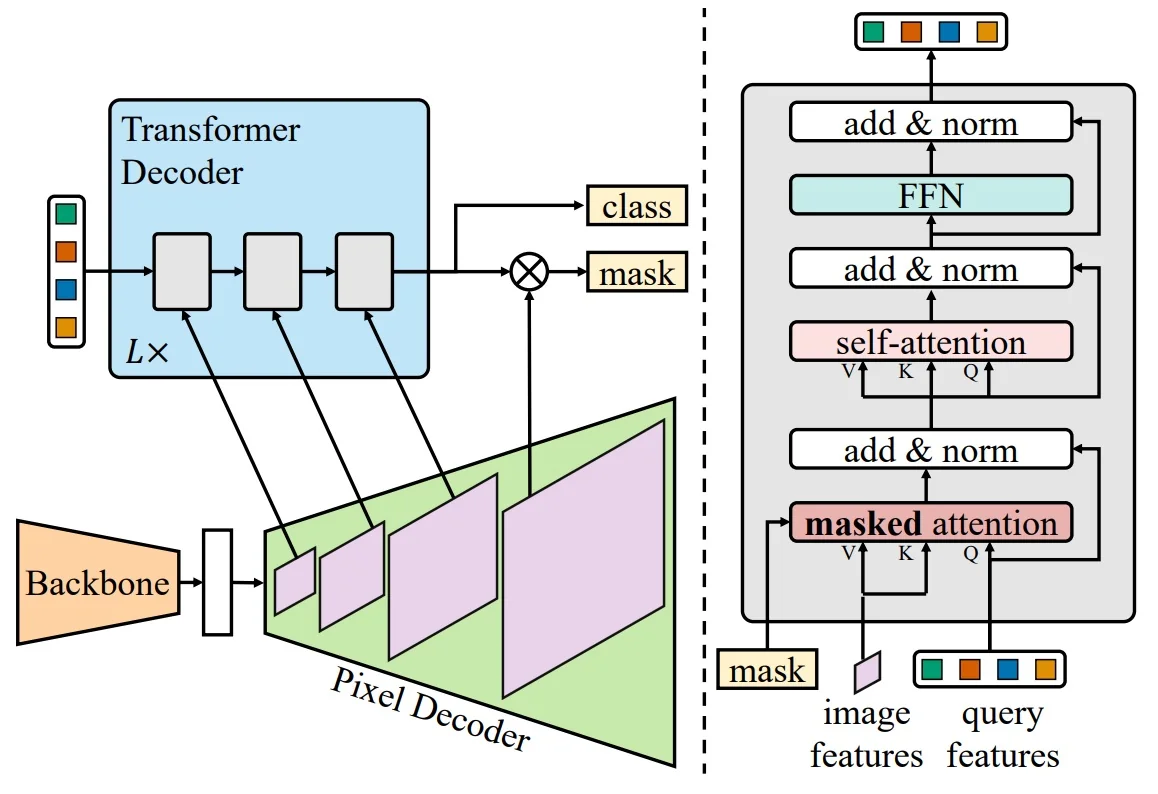

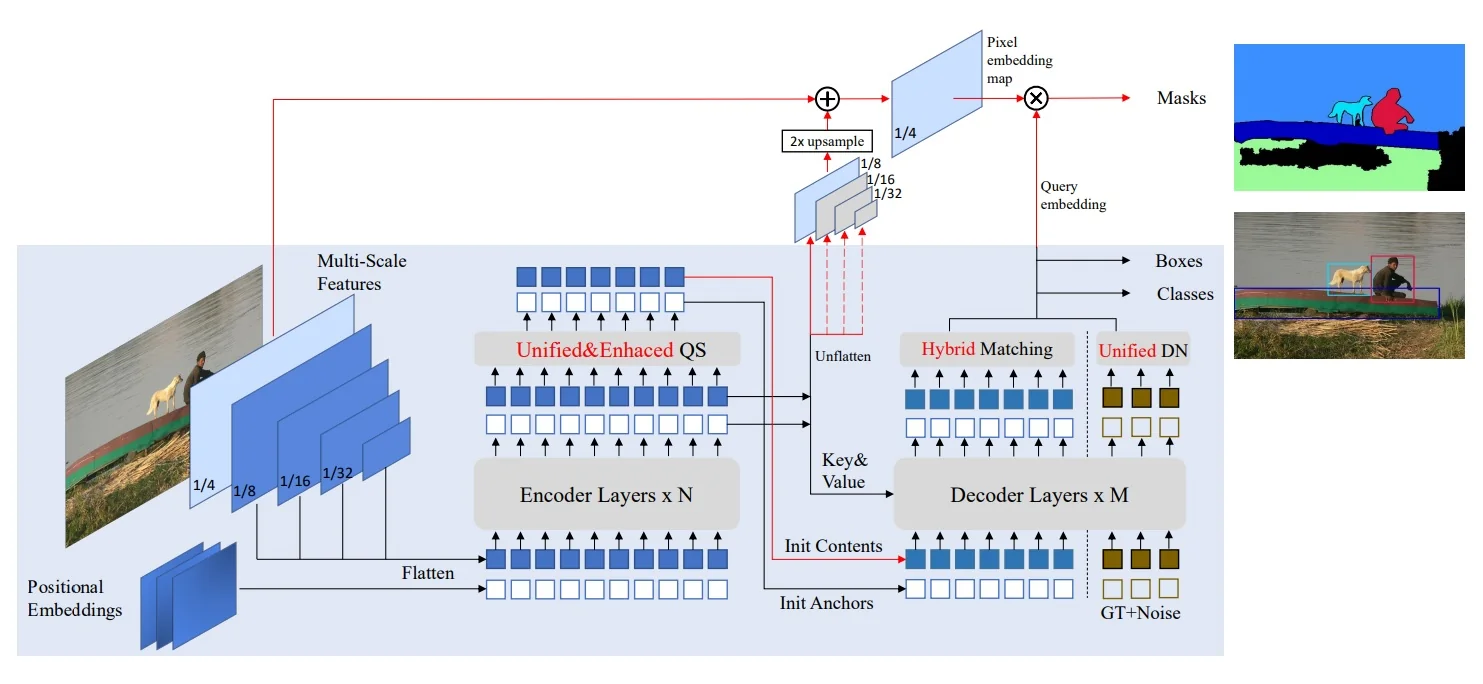

Enrichment 15.7: Striding Towards SOTA Image Segmentation

Foundational segmentation systems By late 2025, modern segmentation has consolidated around two complementary families of models:

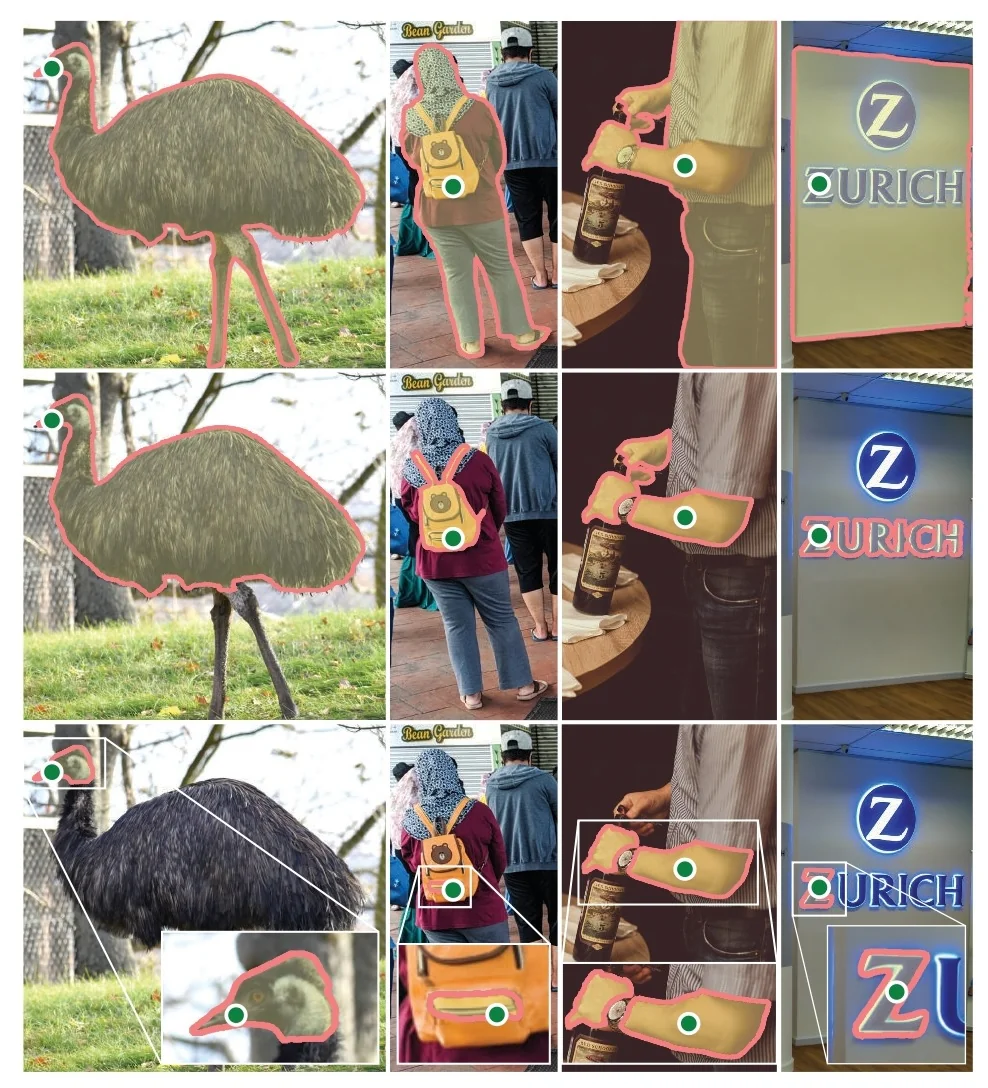

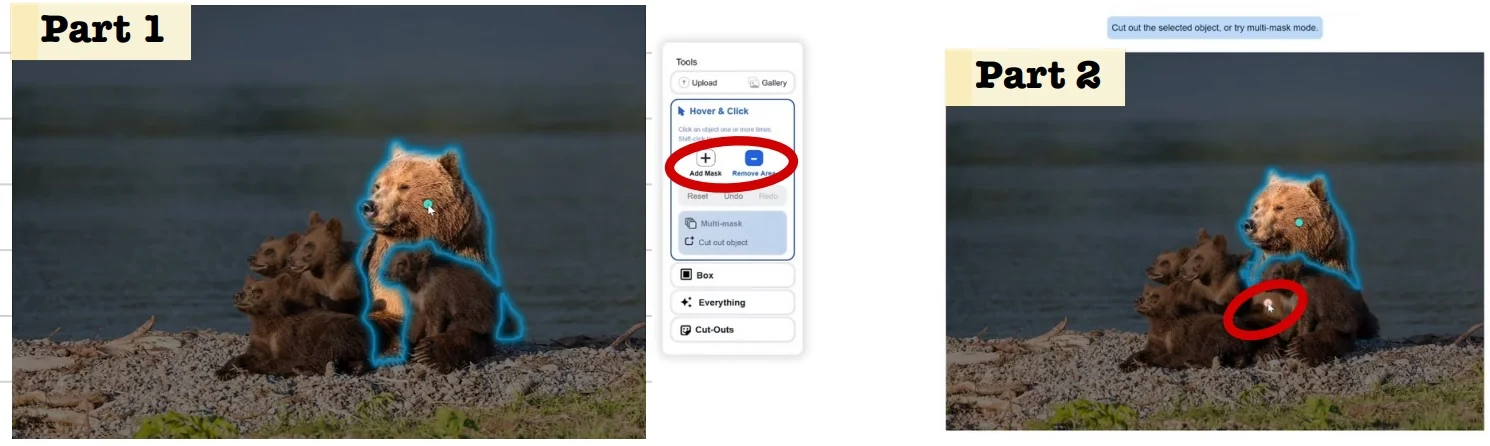

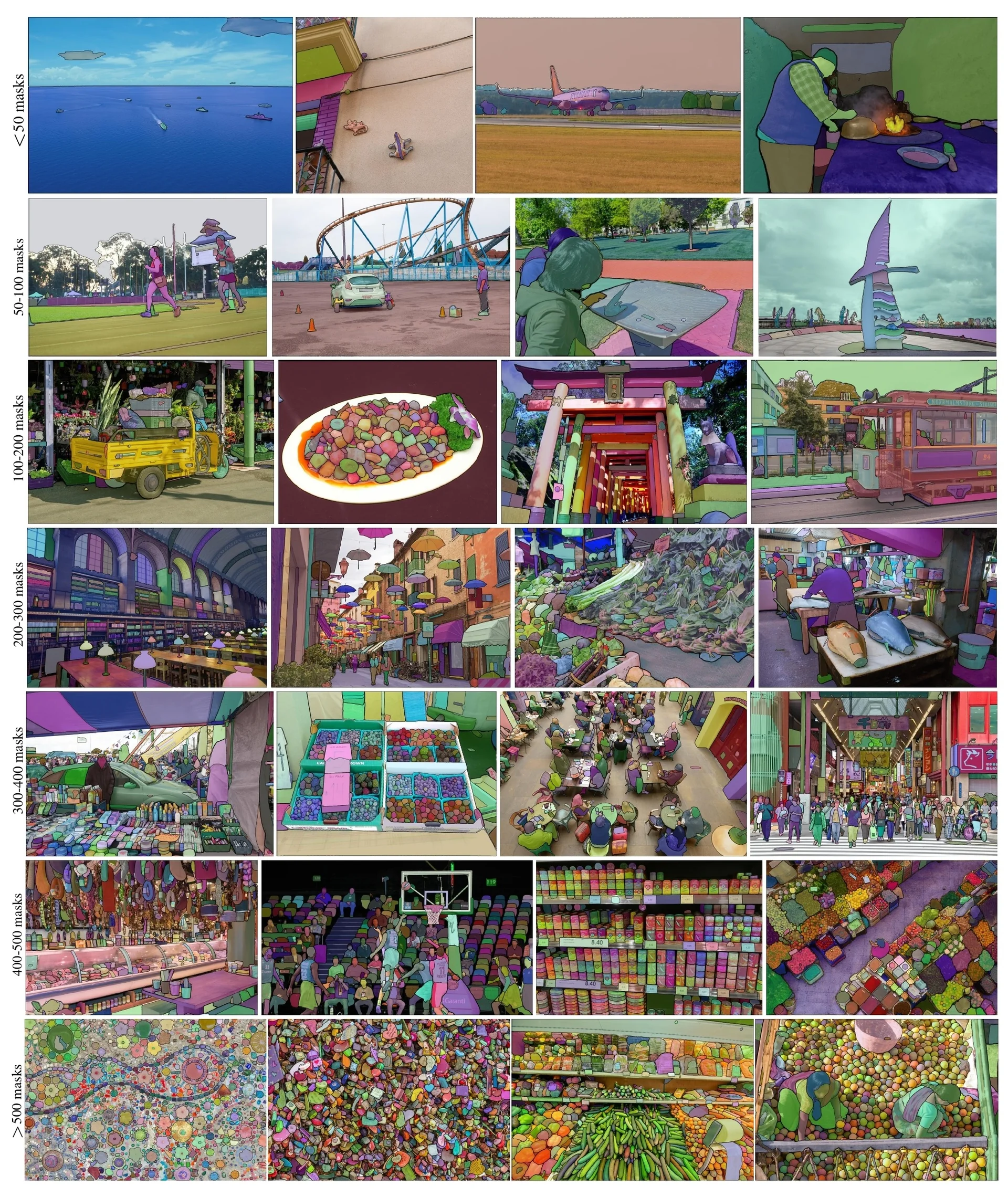

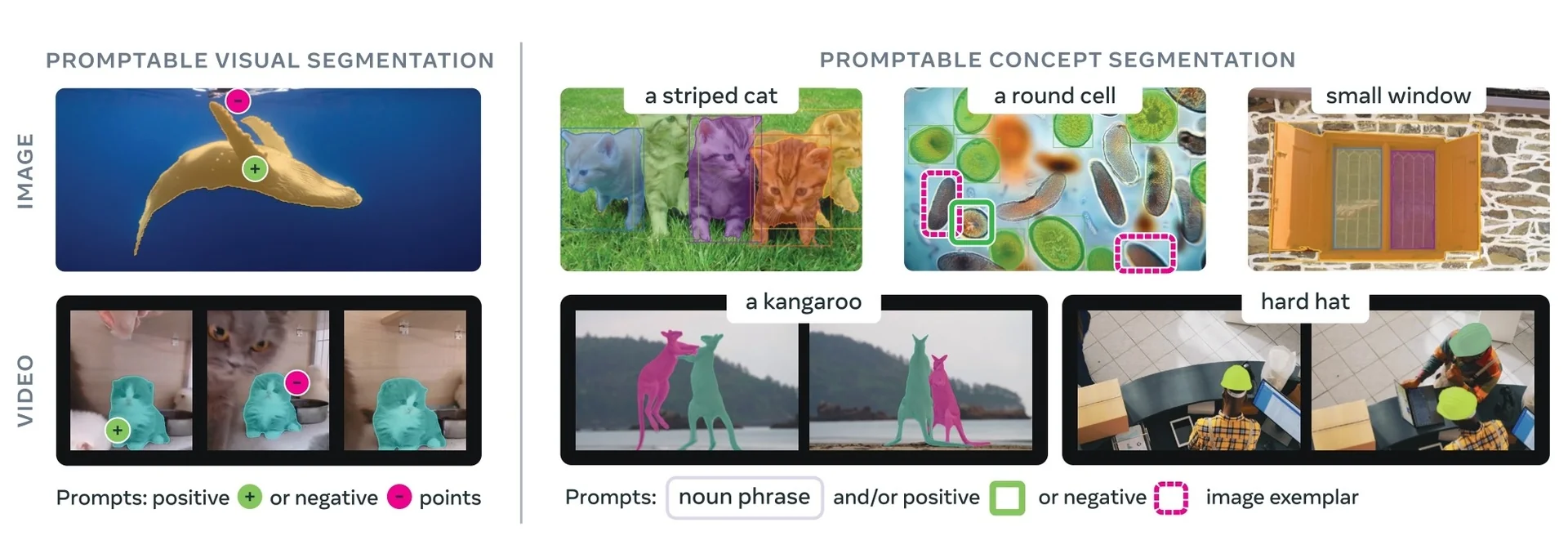

- Promptable foundation models (e.g., SAM, SAM 2, SAM 3) treat segmentation as answering queries about an image or video. Given sparse prompts—originally points, boxes, and masks, and now increasingly text and visual exemplars—they return high-quality masks, largely independent of any fixed label taxonomy.

- Universal task-trained transformers (e.g., Mask2Former, Mask DINO) treat segmentation as a closed-set prediction problem. They are trained on a fixed label space and directly output semantic, instance, or panoptic predictions for all categories in that taxonomy.

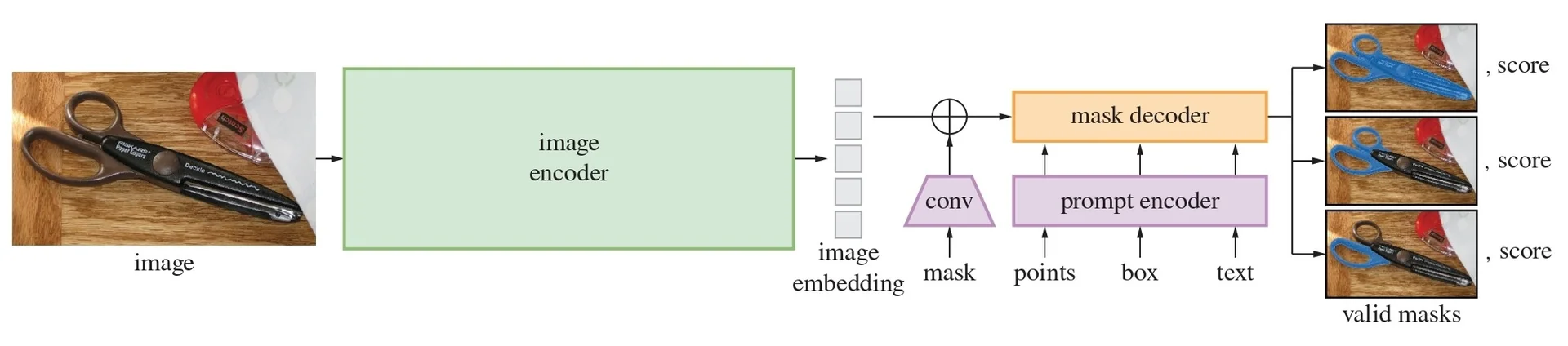

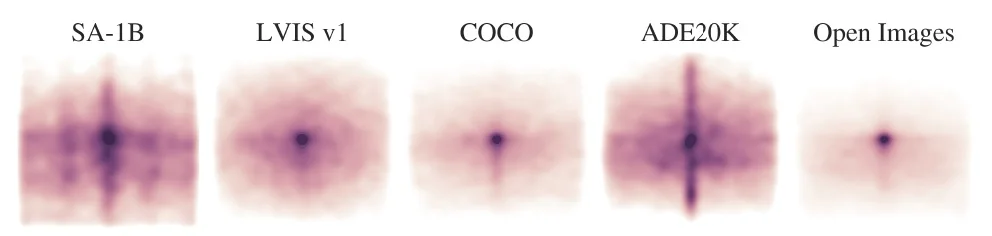

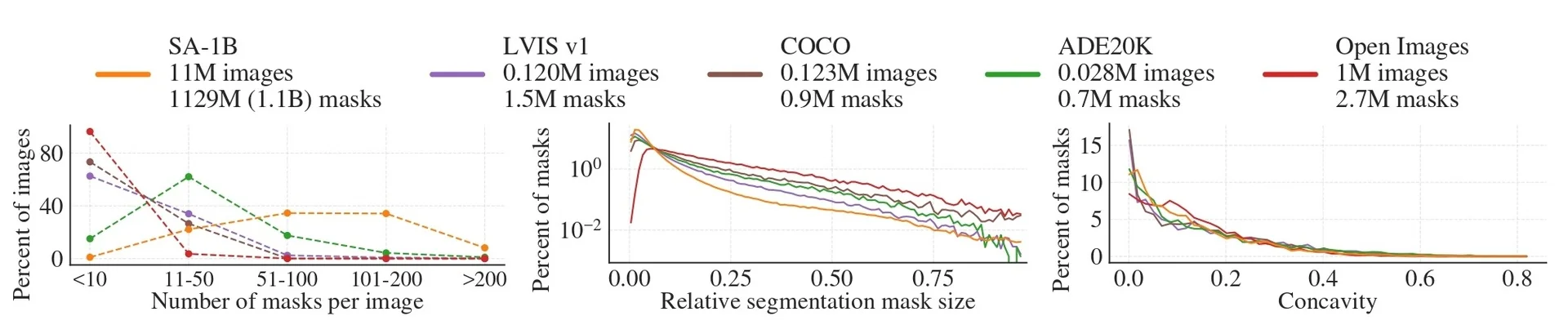

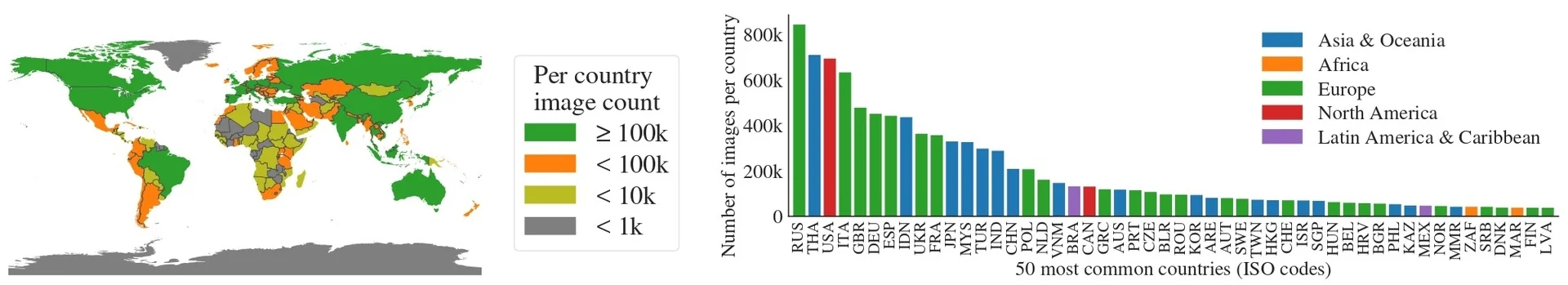

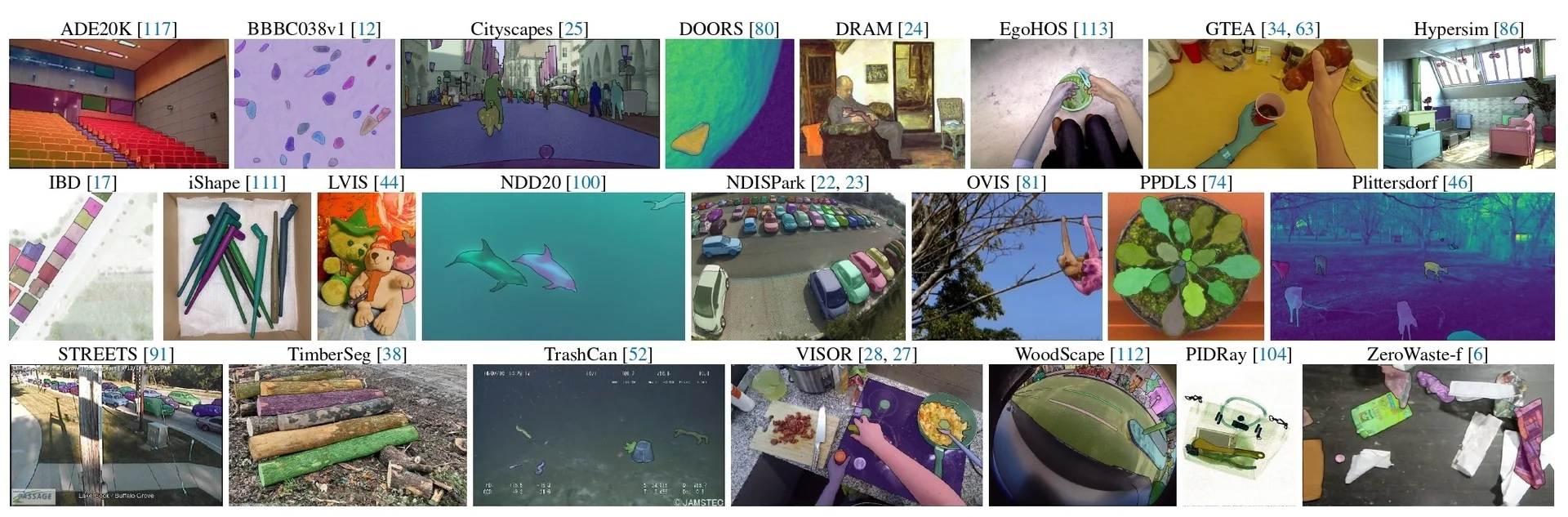

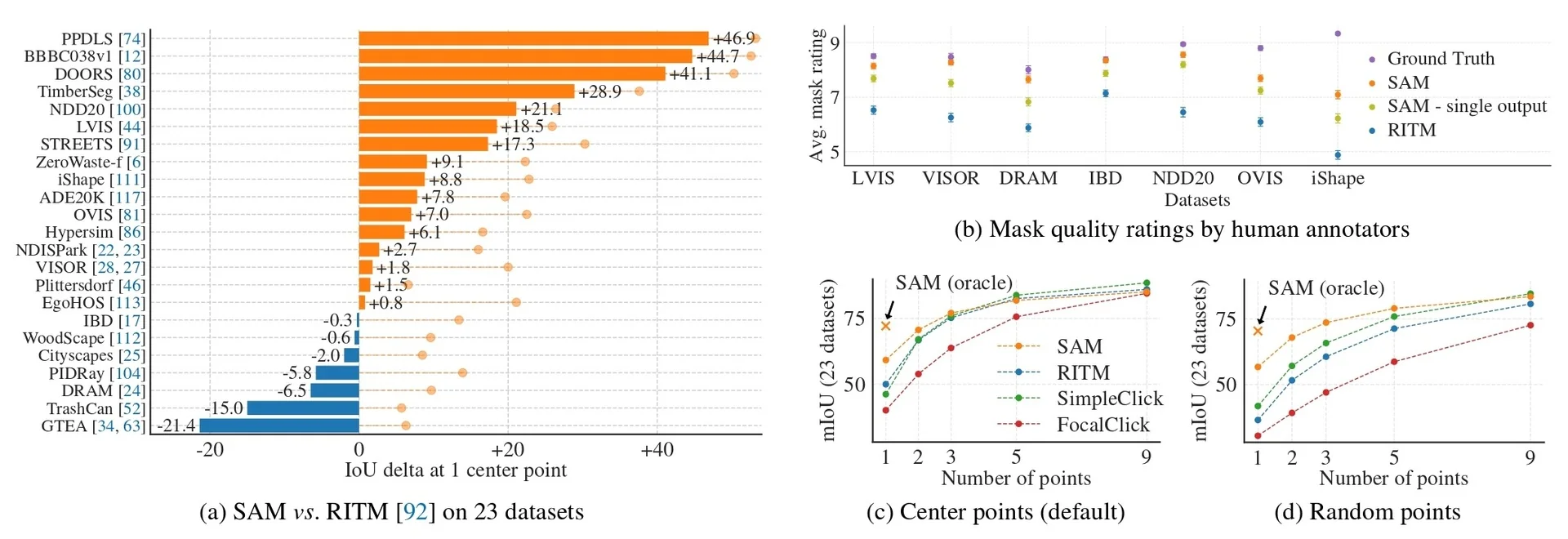

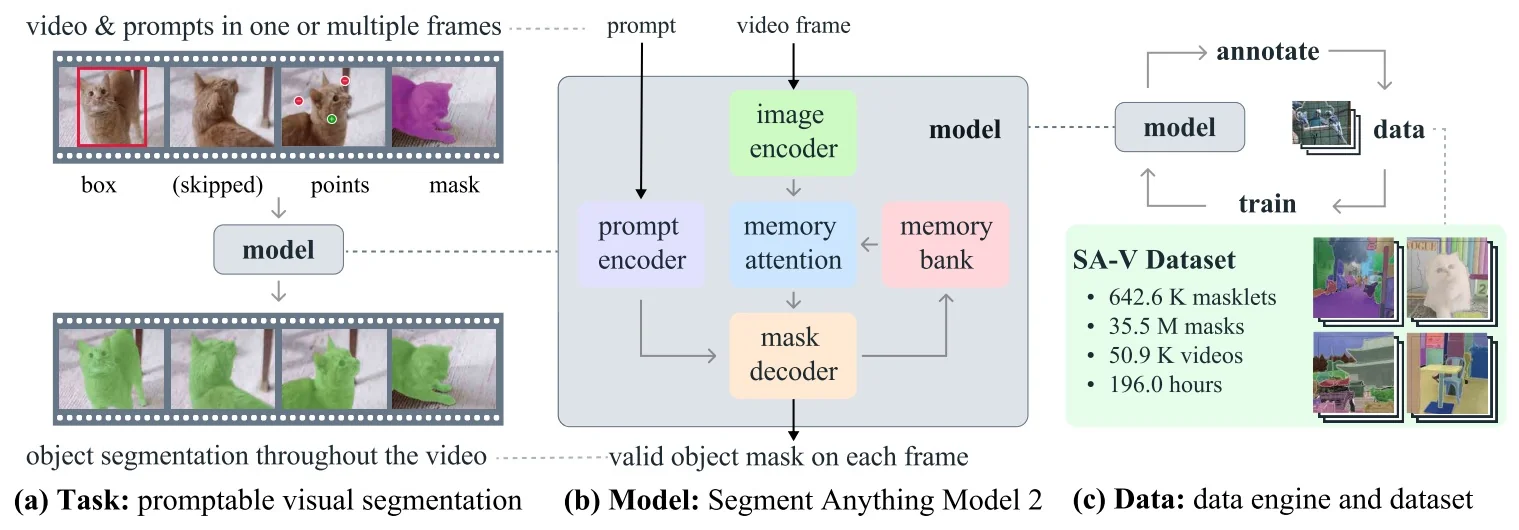

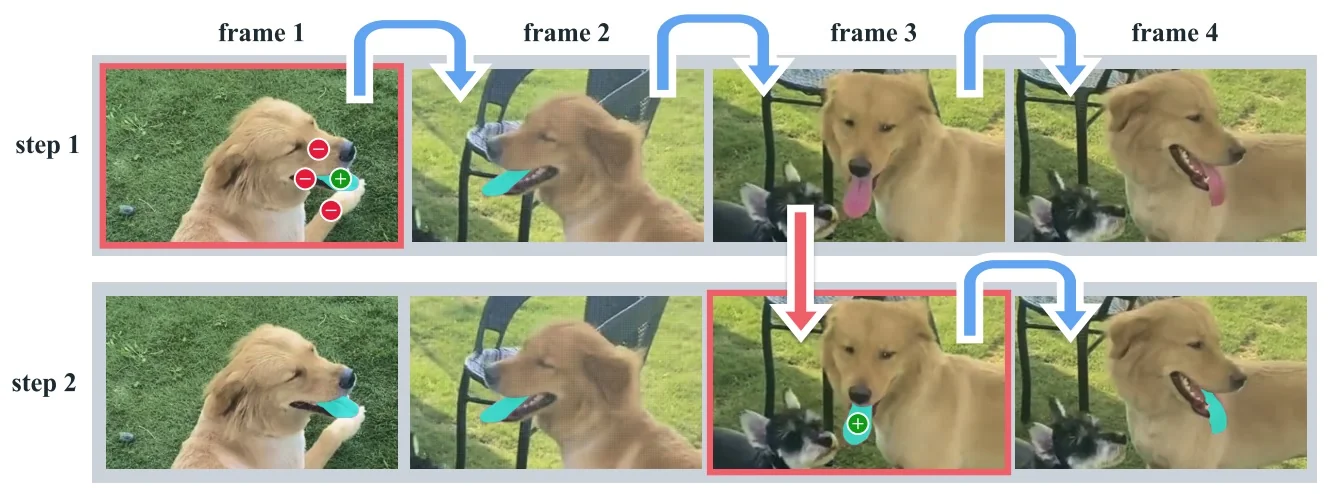

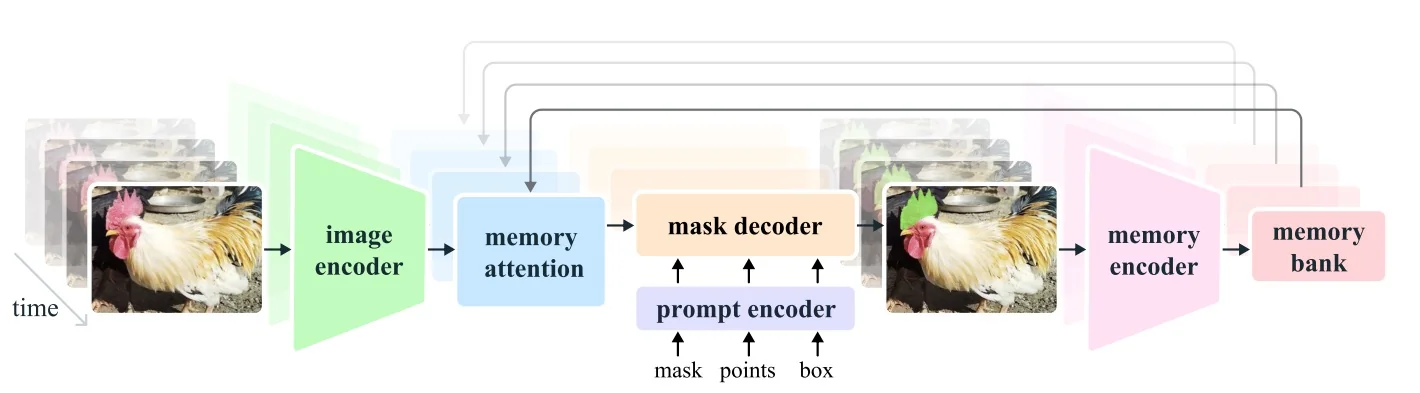

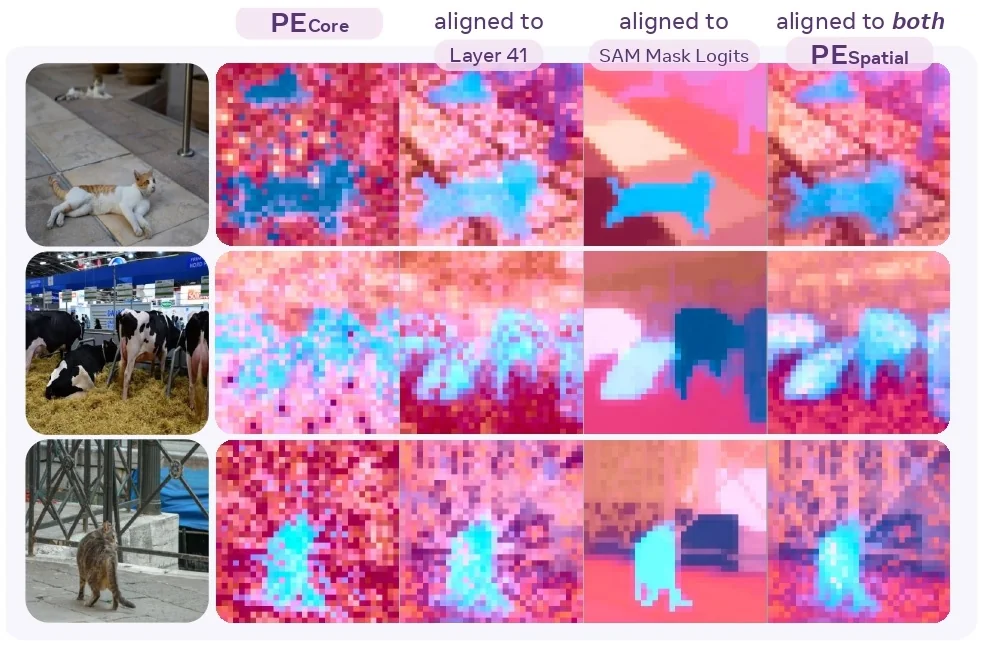

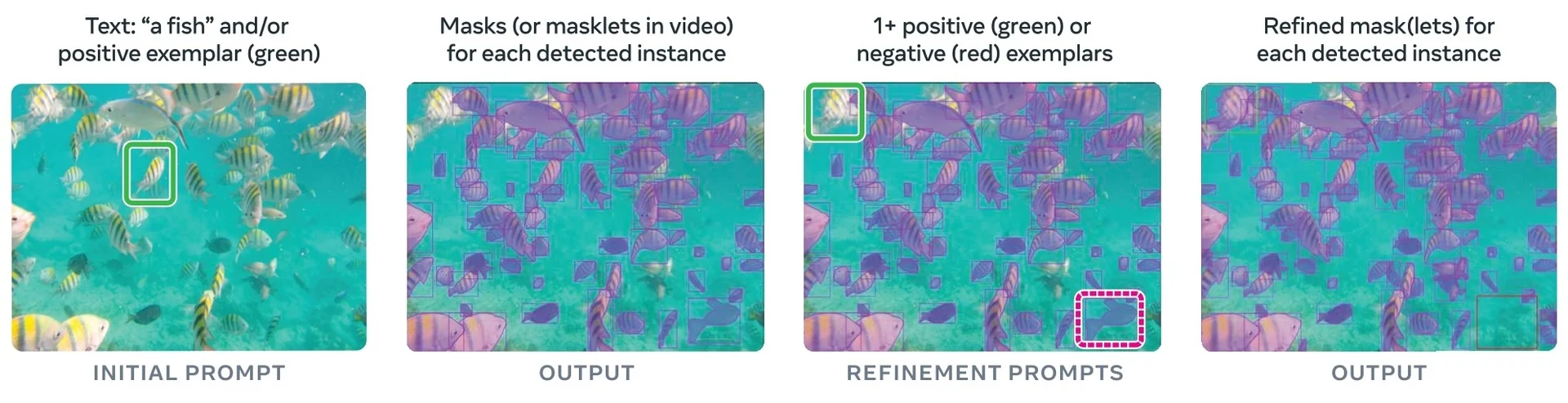

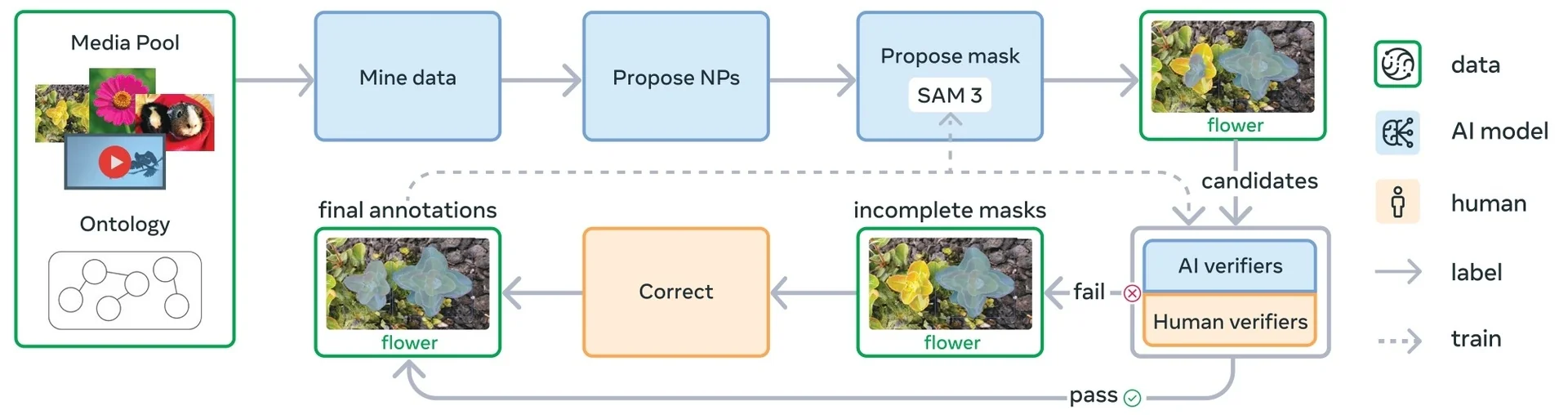

Our focus in this section is on the first family. Segment Anything (SAM) [297] reframed interactive segmentation as large-scale, promptable inference: given geometric hints (points, boxes, or a coarse mask), the model predicts the corresponding object mask, independent of category names. Its capabilities are driven both by a transformer-based encoder–decoder and by the SA-1B data engine, which couples model proposals with large-scale human correction to produce over one billion high-quality masks. Extending this idea from still images to videos, SAM 2 [513] adds a lightweight streaming memory that stores compact state across frames, enabling real-time propagation and interactive correction of masks over long videos; its data engine similarly scales from static images to large video corpora.

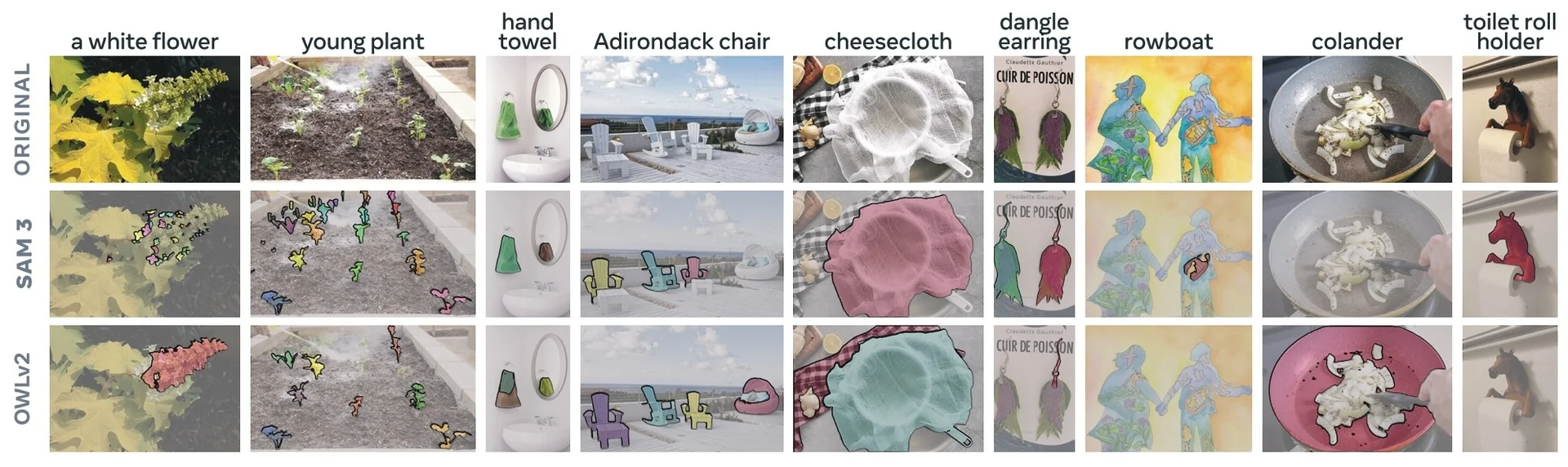

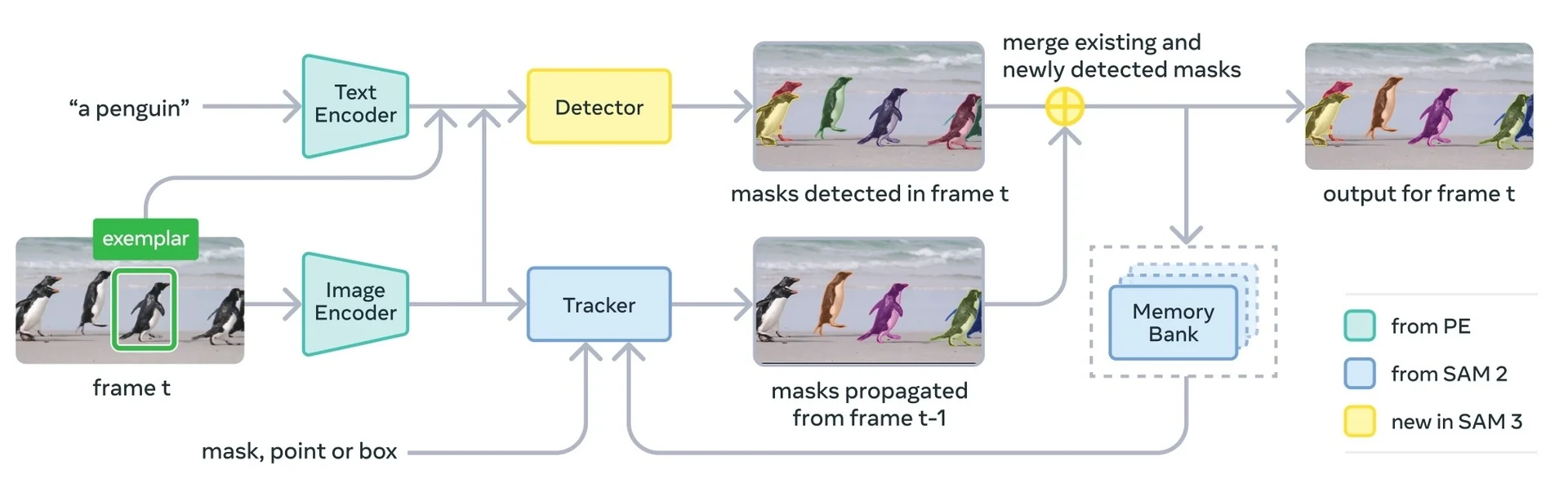

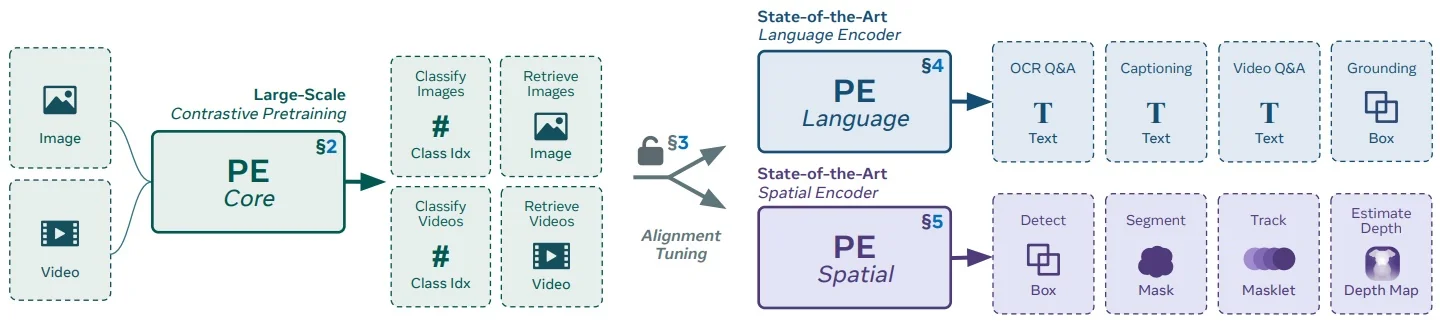

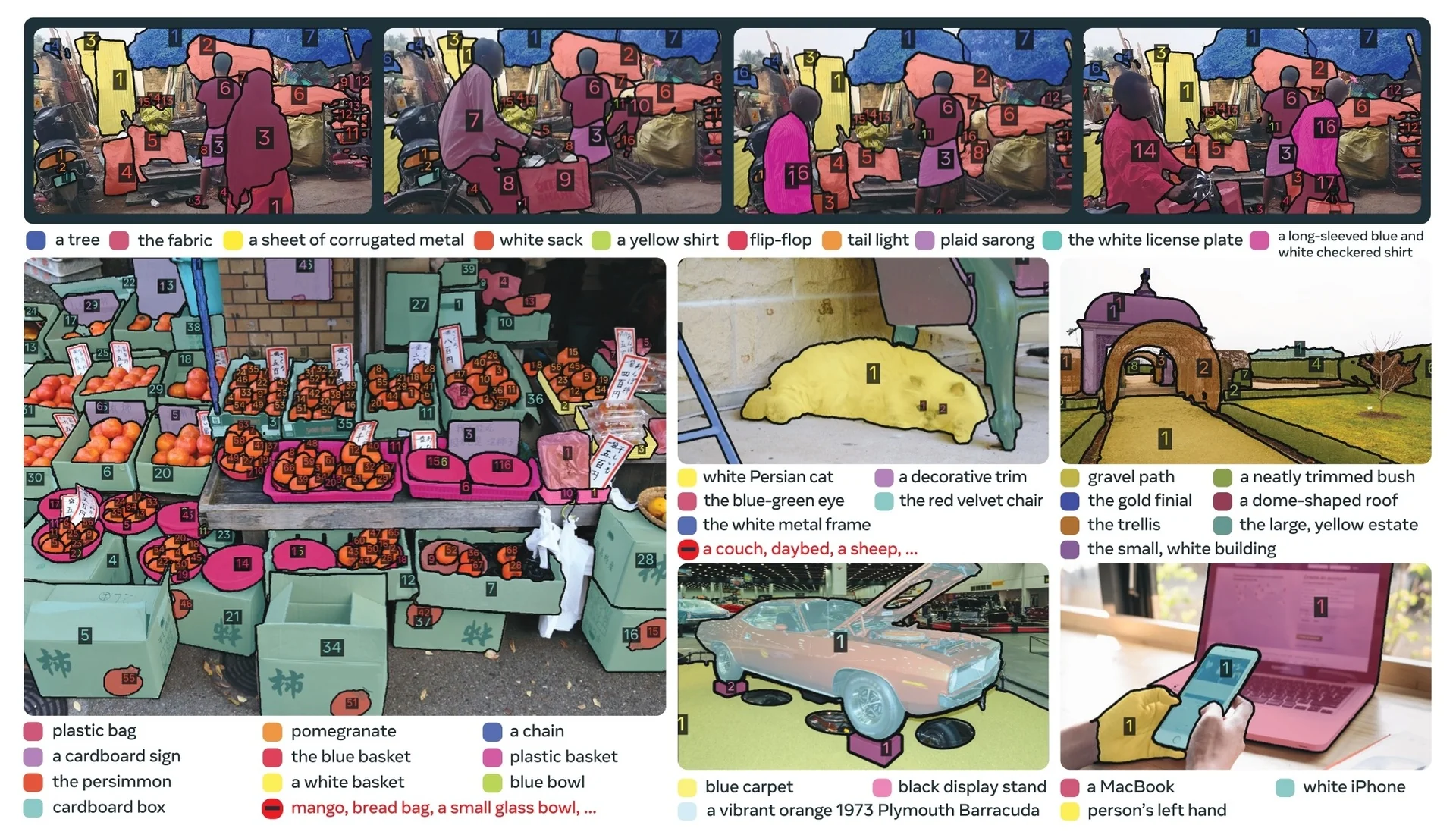

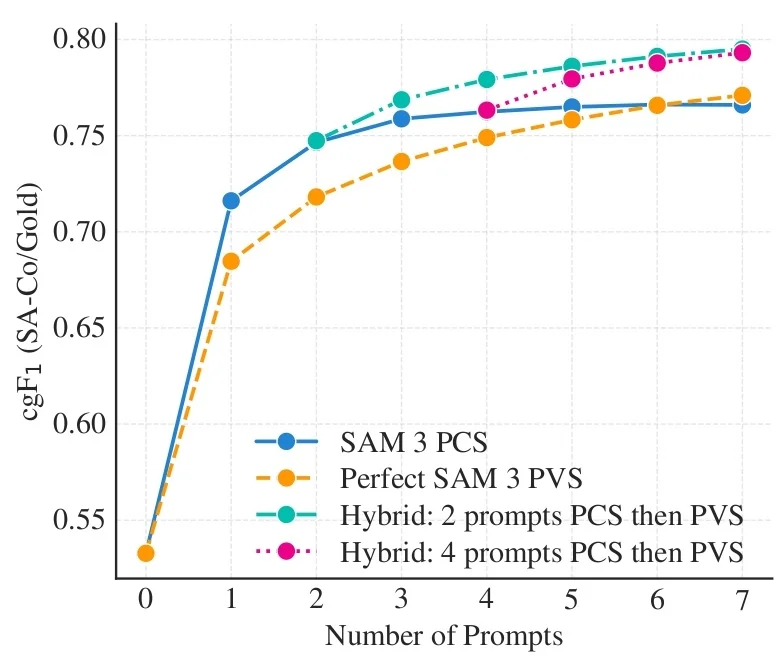

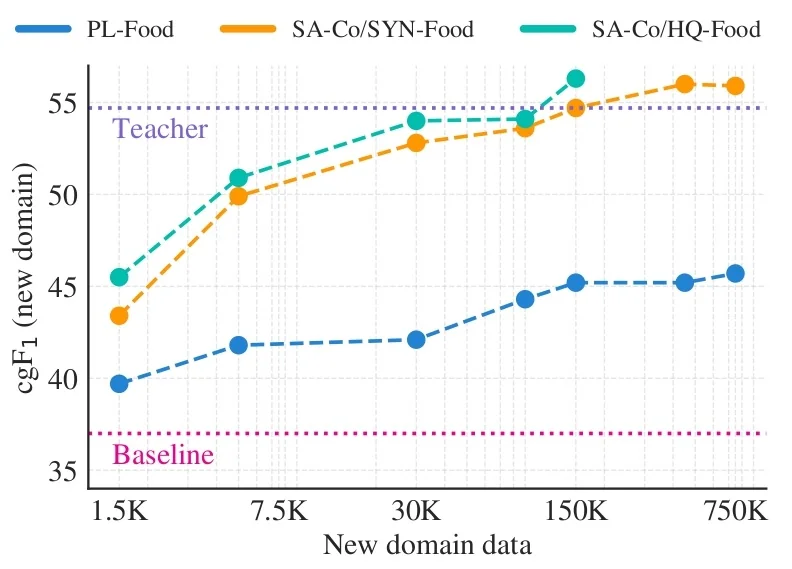

Most recently, SAM 3 [65] unifies this geometric precision with concept-level understanding. Instead of relying on external detectors for text prompts (as in Grounding DINO \(\to \) SAM-style pipelines), SAM 3 natively supports concept prompts: short noun phrases (e.g., “yellow school bus”), image exemplars, or combinations of both. The corresponding task, termed Promptable Concept Segmentation (PCS), takes such prompts and returns segmentation masks and identities for all matching instances in images and videos. Architecturally, SAM 3 shares a vision backbone between an image-level detector and a memory-based video tracker, and introduces a presence head that decouples recognition (“is this concept present here?”) from localization, improving open-vocabulary detection and tracking. In the remainder of this subsection we will treat the SAM family (SAM, SAM 2, SAM 3) as canonical examples of promptable segmentation; later sections return to SAM 2 and SAM 3 in more architectural detail.

In parallel, a second line of work focuses on task-specific, closed-world performance. Universal transformers such as Mask2Former [99] and Mask DINO [330] (covered later in this chapter) are trained to jointly solve semantic, instance, and panoptic segmentation on a fixed label set (e.g., COCO, Cityscapes), typically achieving state-of-the-art mIoU/PQ when the deployment taxonomy matches the training one. Their outputs are directly aligned with benchmark metrics and do not require user prompts at inference time.

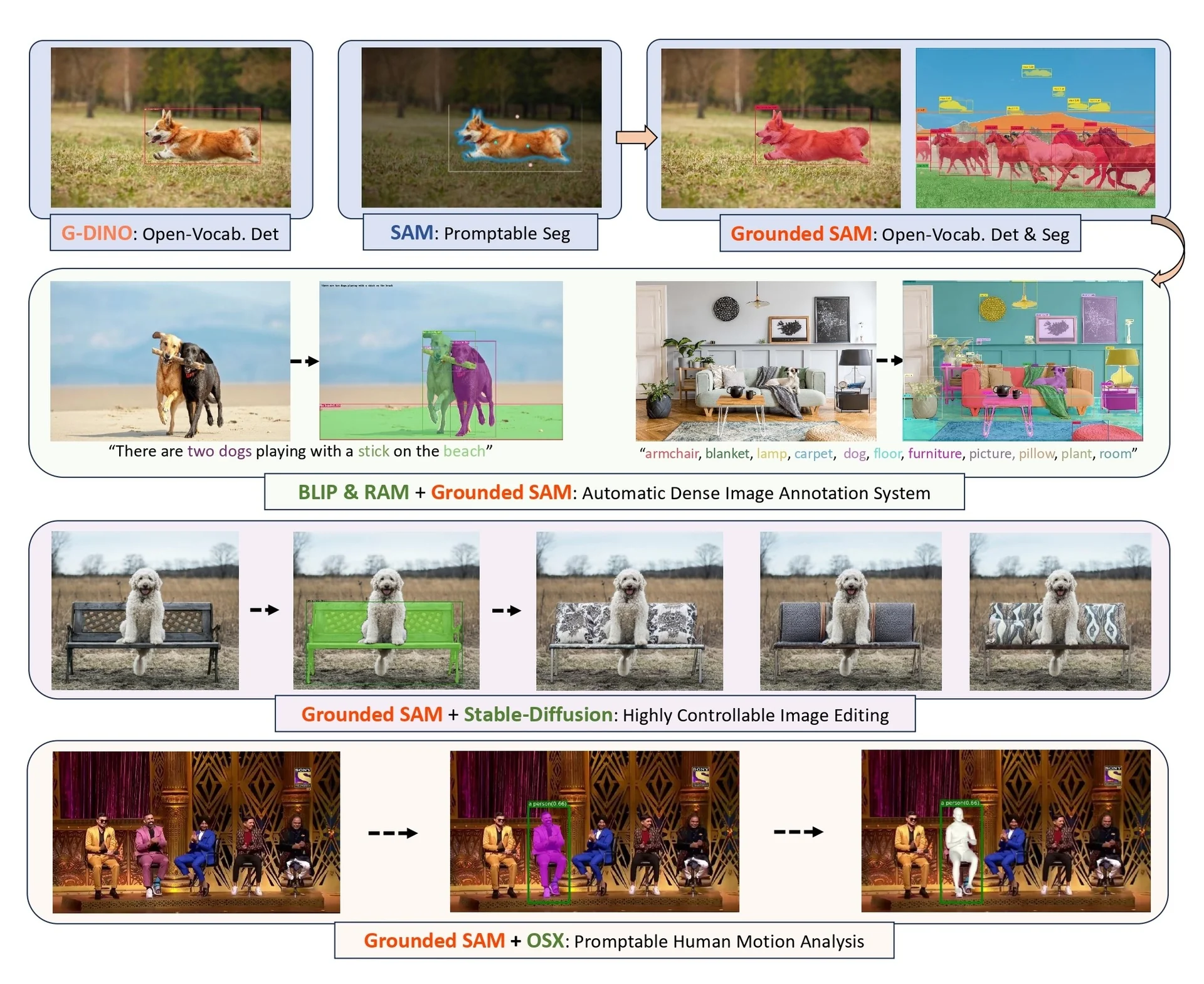

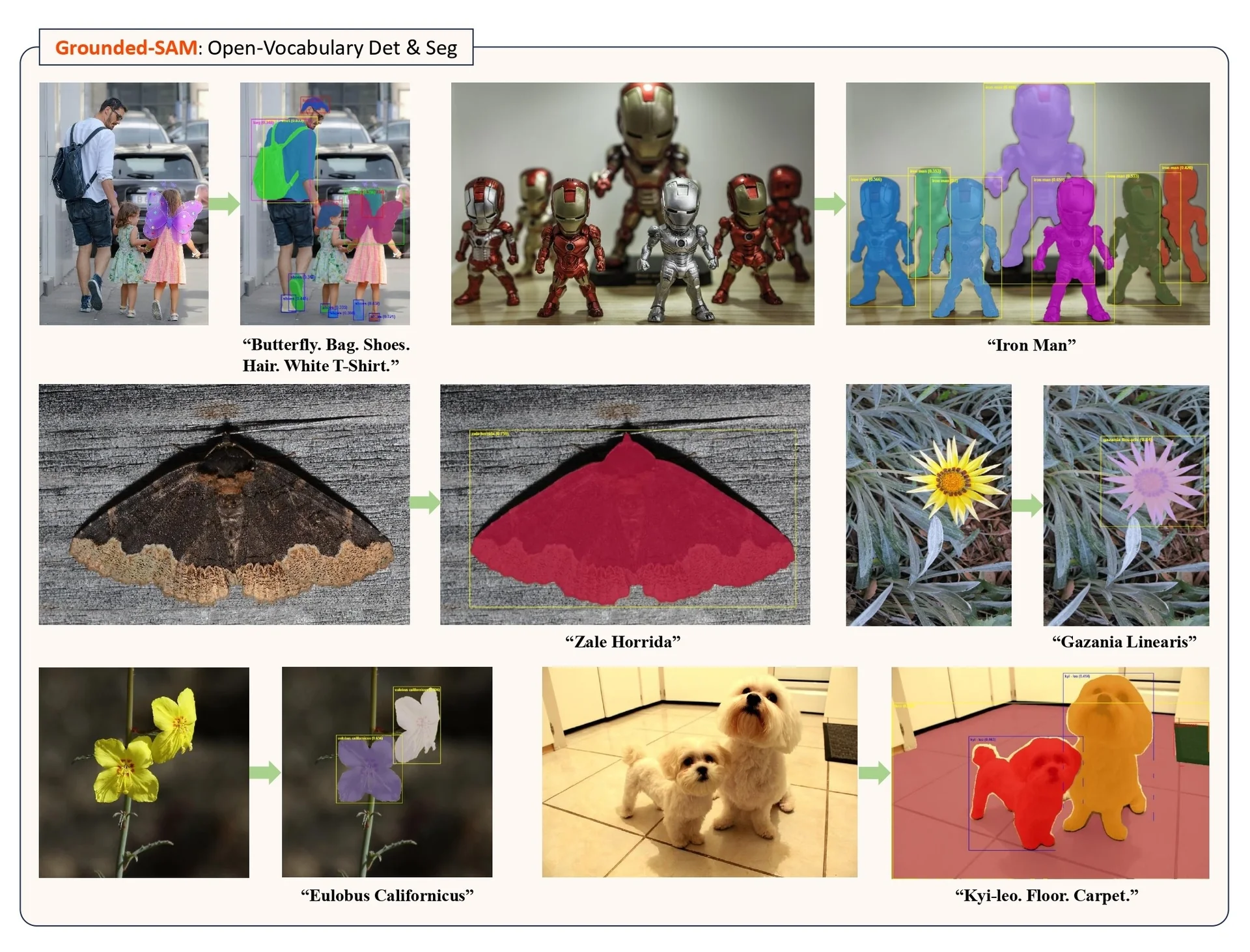

Text-grounded segmentation: composite vs native A third, closely related direction is text-grounded segmentation. Before SAM 3, open-vocabulary segmentation typically relied on composite pipelines. Systems such as Grounding DINO [376] or OWLv2 [432] first performed grounding—mapping text prompts to boxes and labels—and then SAM or SAM 2 converted those boxes or points into precise masks. This pattern, often referred to as Grounded SAM [524], explicitly splits the problem into two stages: (1) a vision–language detector for text-to-box grounding, and (2) a promptable segmenter for box-to-mask refinement.

Conceptually, this brings us full circle to the two-stage design of classical detectors such as Mask R-CNN [209]. There, a Region Proposal Network (RPN) first generates category-agnostic boxes, and a second-stage head turns each box into class scores and a binary mask. Grounded SAM follows the same high-level pattern—“boxes first, masks second”—but with a crucial difference in scale and modularity. Instead of a single backbone with lightweight heads, it chains two large foundation models: a vision–language detector (Grounding DINO/OWLv2) and a high-capacity segmenter (SAM/SAM 2). This is attractive from an engineering perspective, because each component can be trained, deployed, and upgraded independently, but it also means that a single input triggers two expensive forward passes and two sets of model weights.