Lecture 14: Object Detectors

14.1 Beyond R-CNN: Advancing Object Detection

In the previous chapter we focused on what object detection is (bounding boxes, IoU, AP/mAP, NMS) and briefly contrasted closed-set vs. open-set detection. We now turn to how detectors are actually built, starting from the first successful CNN-based systems.

R-CNN showed that applying a deep convolutional network to region proposals could dramatically outperform traditional pipelines, firmly establishing CNNs as the backbone of modern detectors. The downside was efficiency: for each image, R-CNN runs a separate CNN forward pass on roughly \(\sim 2000\) region proposals, followed by separate SVMs and bounding box regressors. This heavy, multi-stage pipeline makes R-CNN slow to train and far too expensive for real-time or large-scale deployment.

The rest of this chapter follows the historical path toward more efficient and integrated detectors:

- Fast R-CNN shares convolutional features across all proposals and introduces RoI Pooling / RoIAlign to speed up per-region processing.

- Faster R-CNN learns region proposals with a Region Proposal Network (RPN), removing the last major hand-crafted component.

- Feature Pyramid Networks (FPNs) exploit multi-scale feature maps to improve detection of small and large objects.

- Single-stage and anchor-free detectors such as RetinaNet and FCOS further simplify the pipeline by predicting boxes and classes densely in one pass.

- YOLO-style models show how far we can push real-time, single-shot detection in practice.

Together, these CNN-based detectors form the “classical toolkit” of object detection. While they are not widely used today (besides YOLO), as we will see, many of their core ideas—feature sharing, bounding box regression, multi-task losses, and multi-scale features—reappear inside newer architectures as well.

14.1.1 Looking Ahead: Beyond CNN-Based Object Detectors

Even the most refined CNN-based detectors in this chapter share a common structure: convolutional backbones, dense candidate boxes (anchors or per-pixel predictions), and post-processing with NMS. Modern work pushes further toward end-to-end architectures that minimize hand-designed components and treat detection more like a direct set prediction problem.

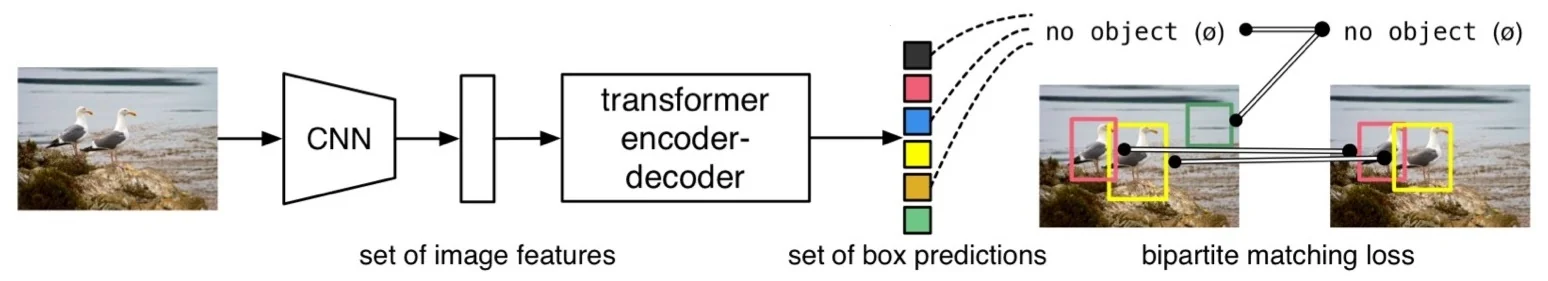

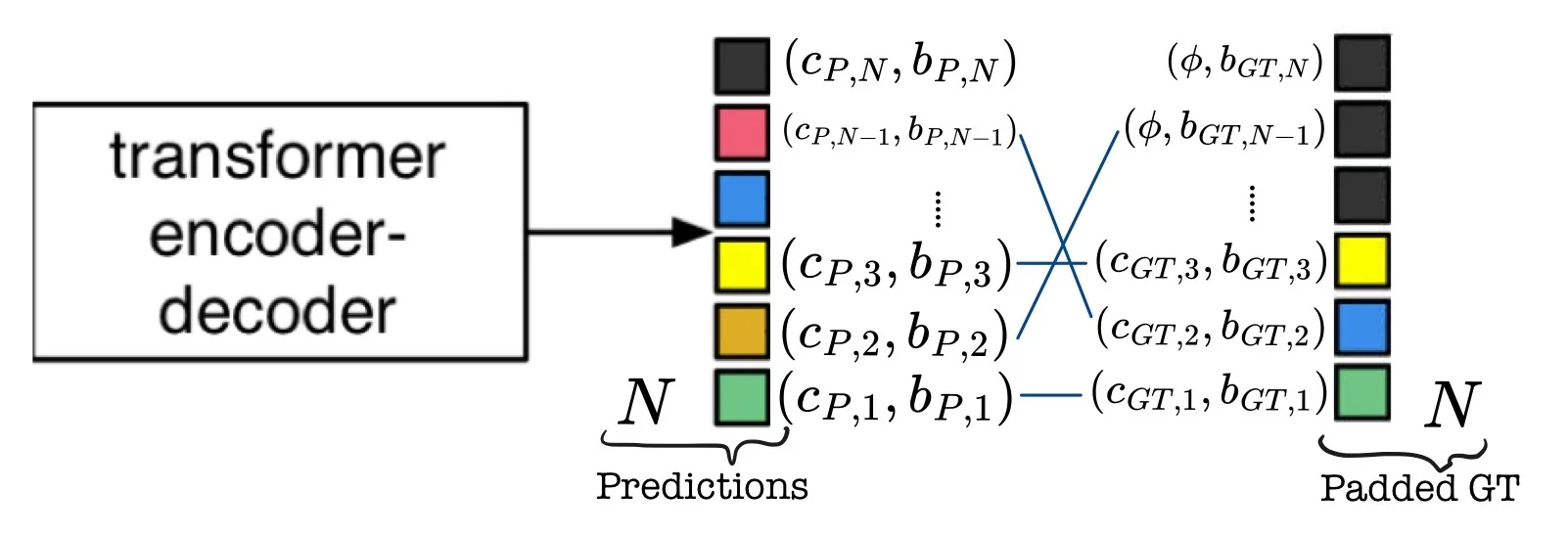

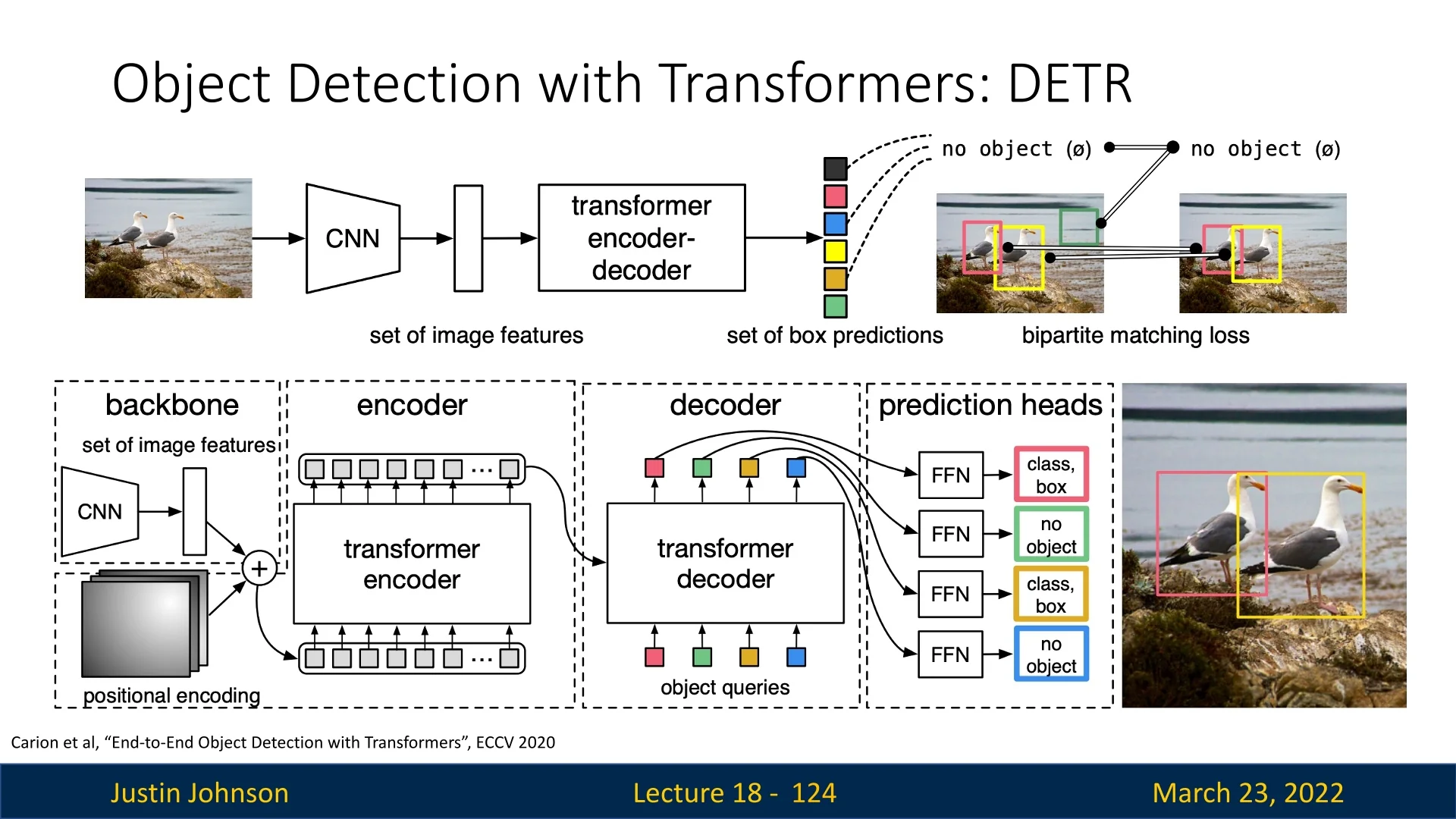

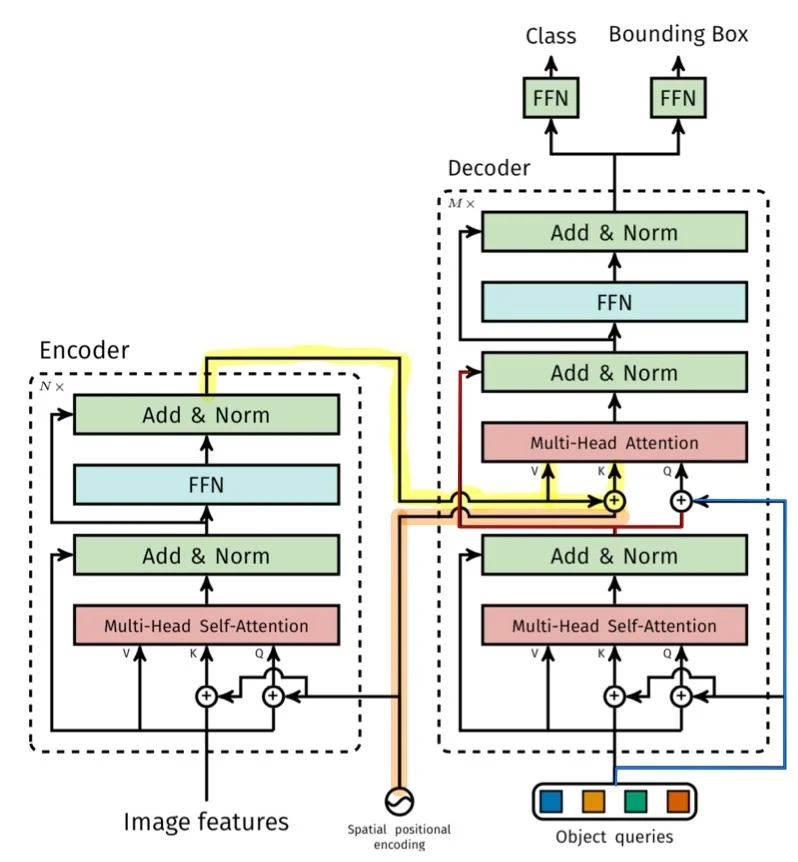

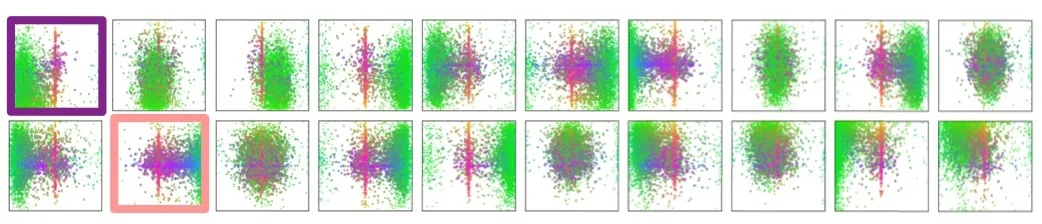

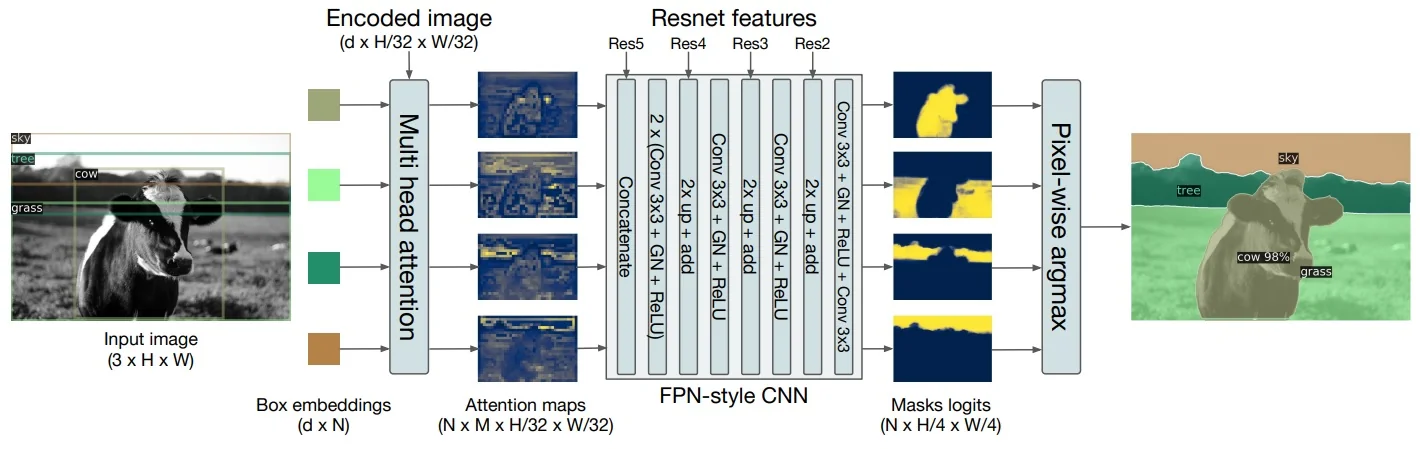

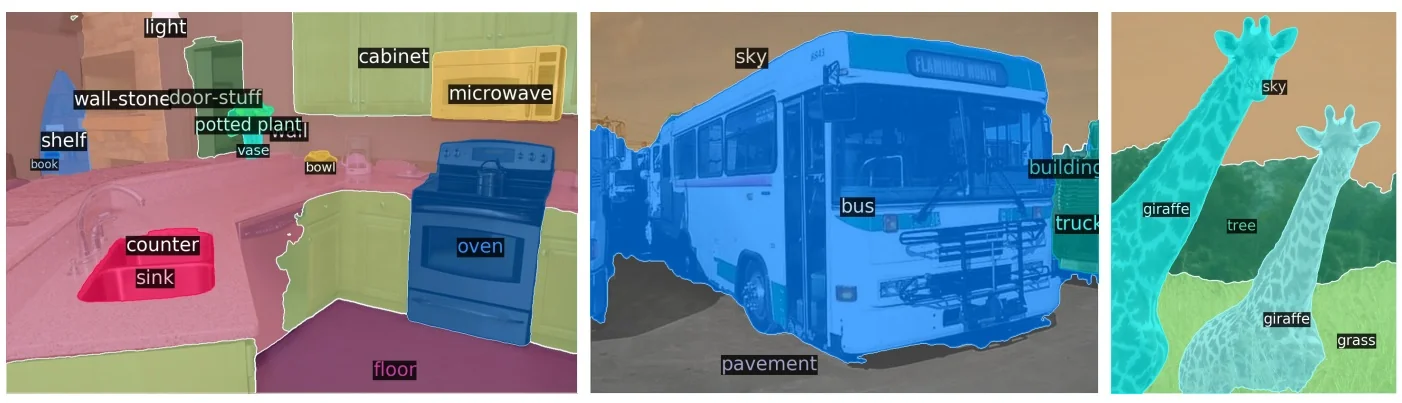

A key milestone is DETR (DEtection TRansformer) [64], which uses transformers and a set-based matching loss to predict a fixed-size set of boxes and labels, removing both region proposals and NMS from the pipeline. Follow-up works such as Re DETR [804] and DINO for detection [327] refine optimization, query design, and training recipes to improve convergence speed and accuracy, while Mask DINO [330] extends these ideas to instance and panoptic segmentation.

At the same time, large vision backbones trained with self-supervision or vision-only pretraining, such as DINOv2 [463] and DINOv3 [569], provide powerful, task-agnostic image representations that can be plugged into many detection heads (Faster R-CNN, RetinaNet, DETR variants) to boost performance with minimal task-specific tuning.

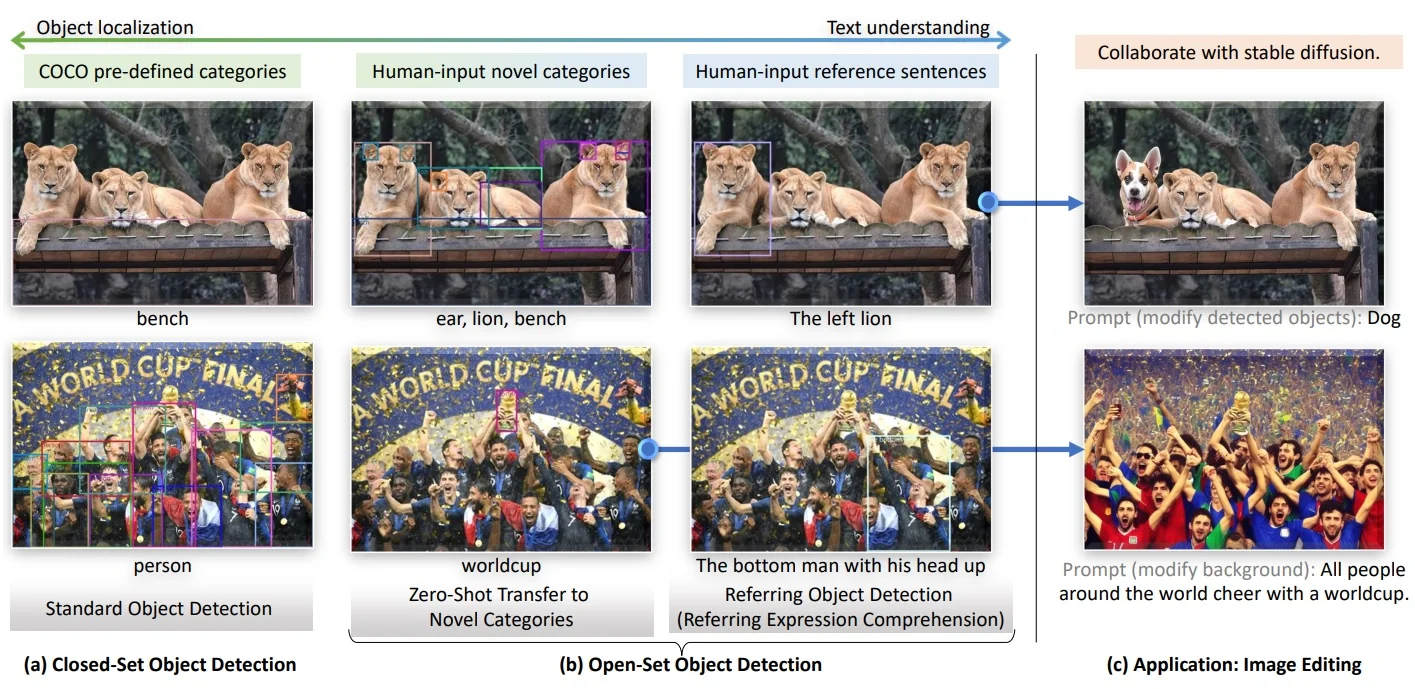

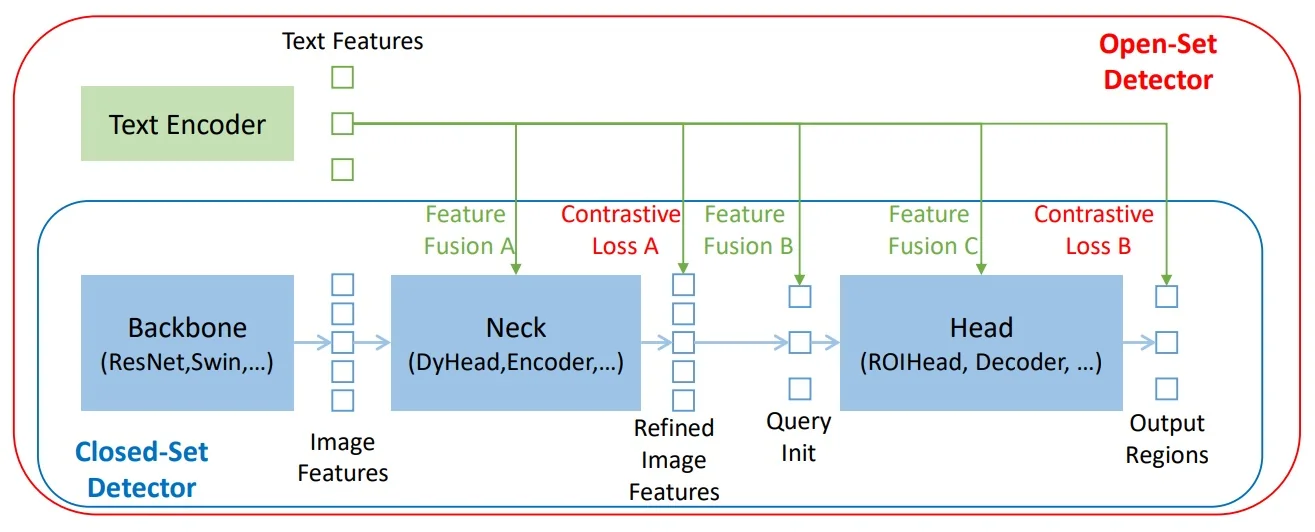

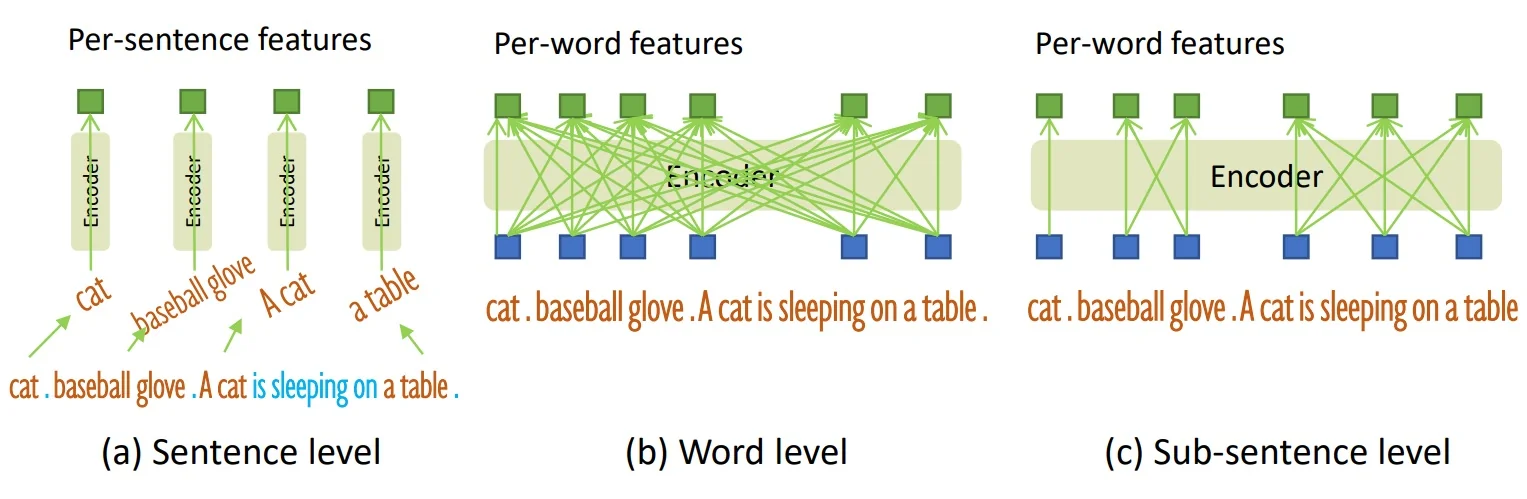

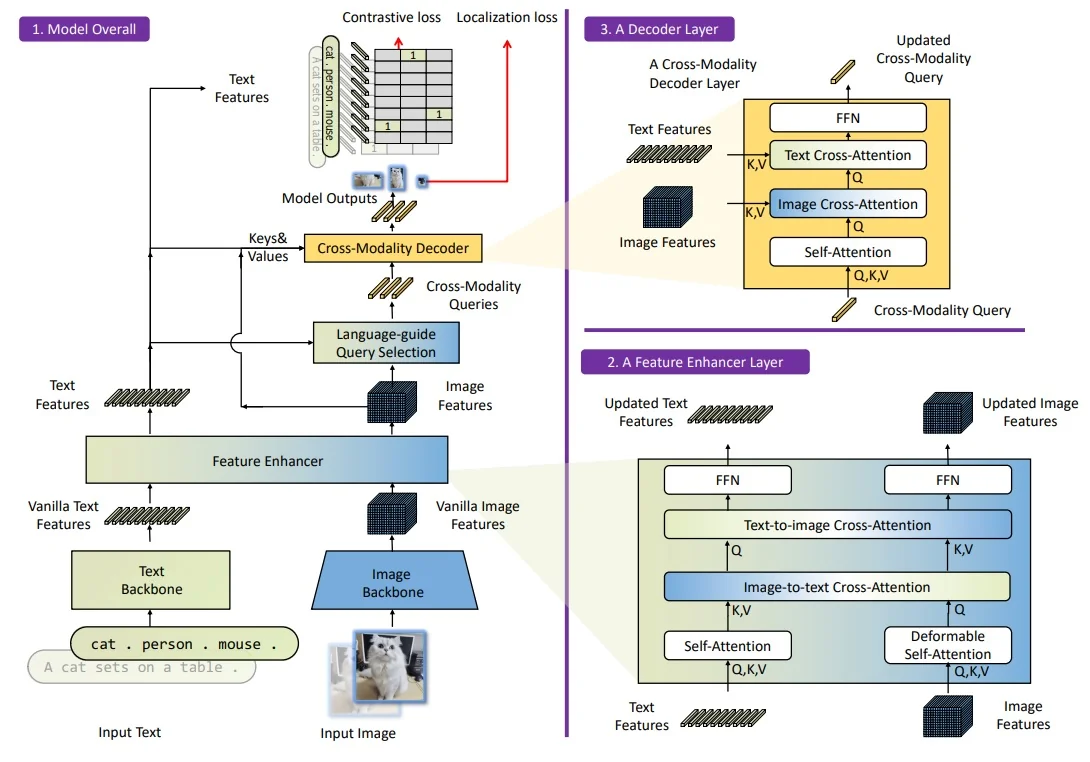

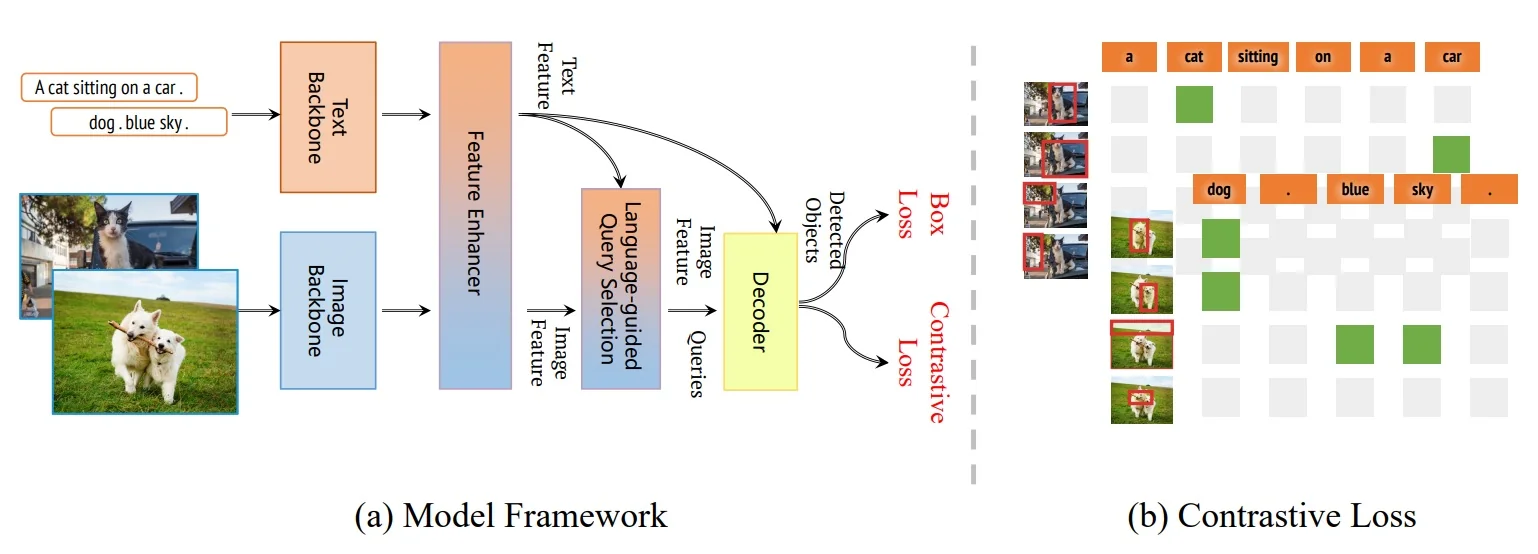

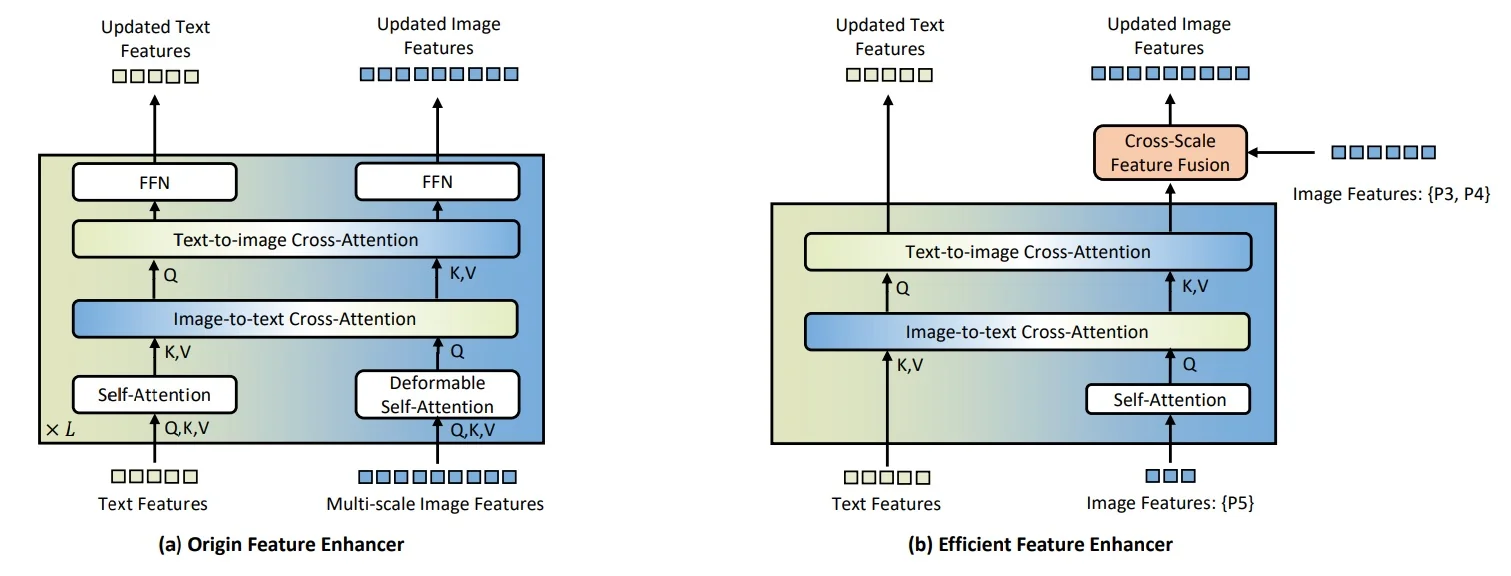

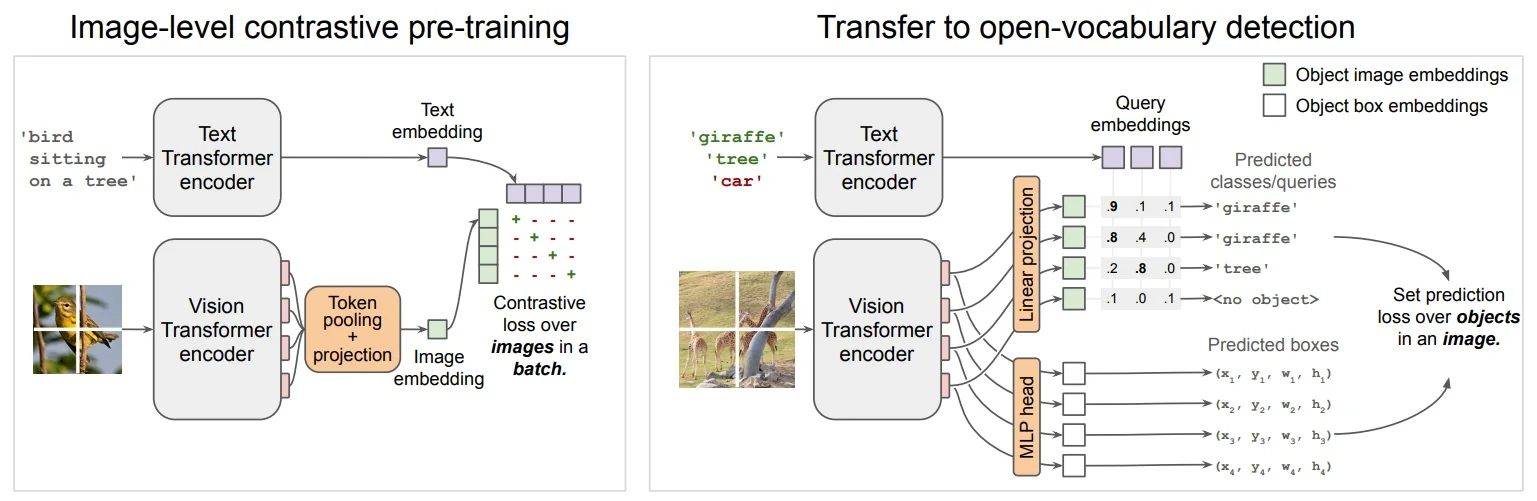

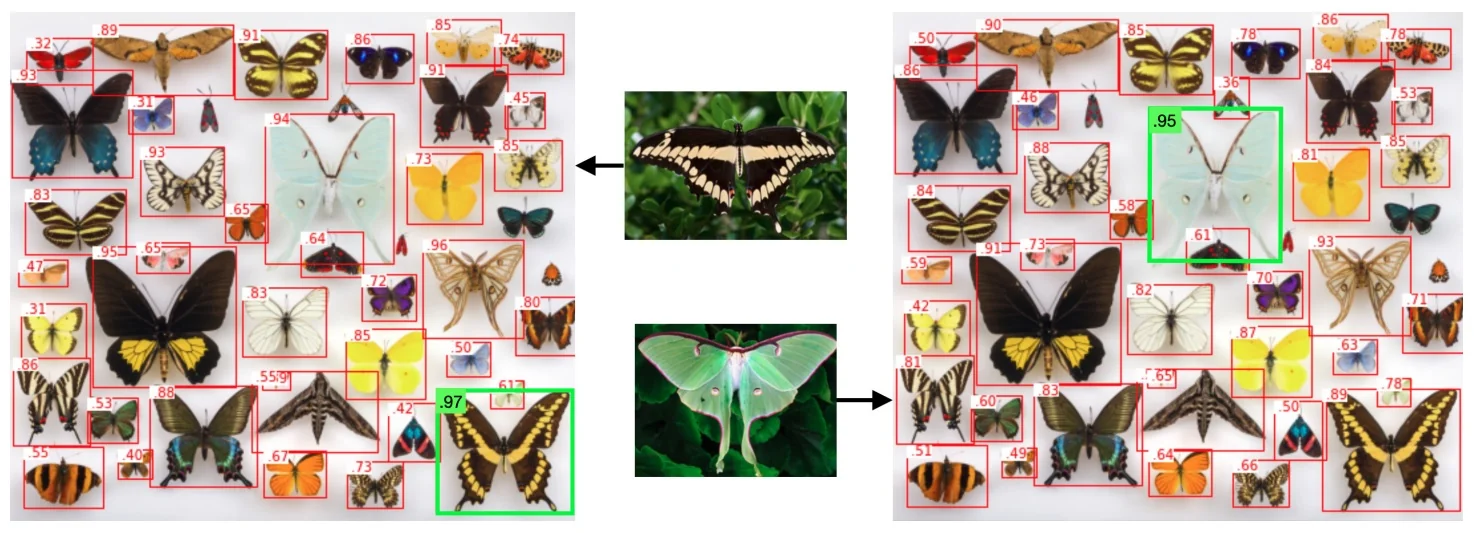

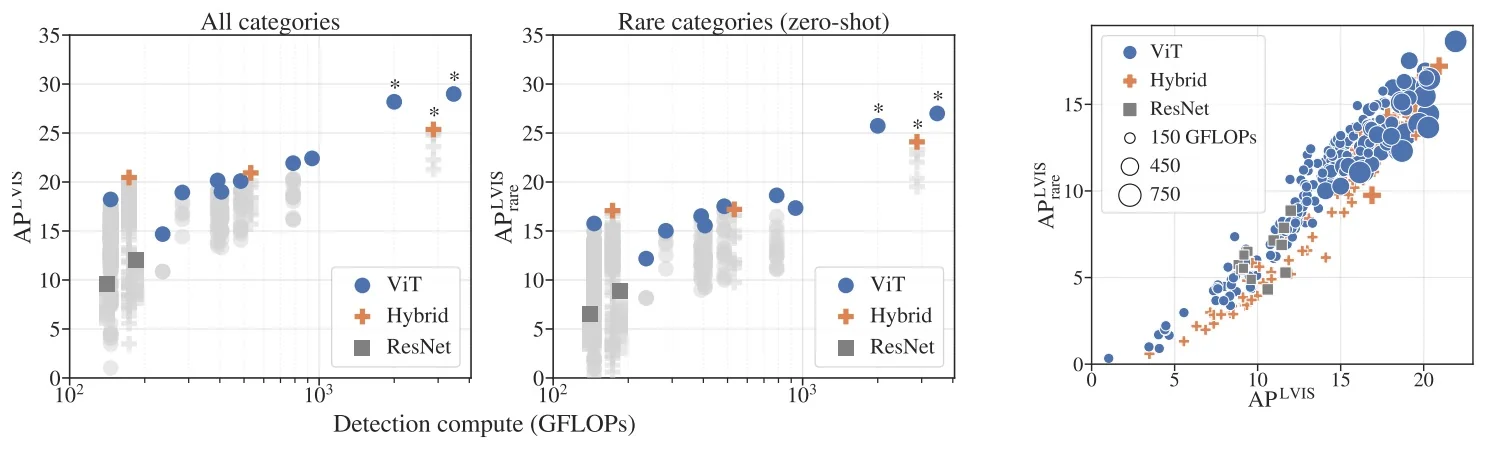

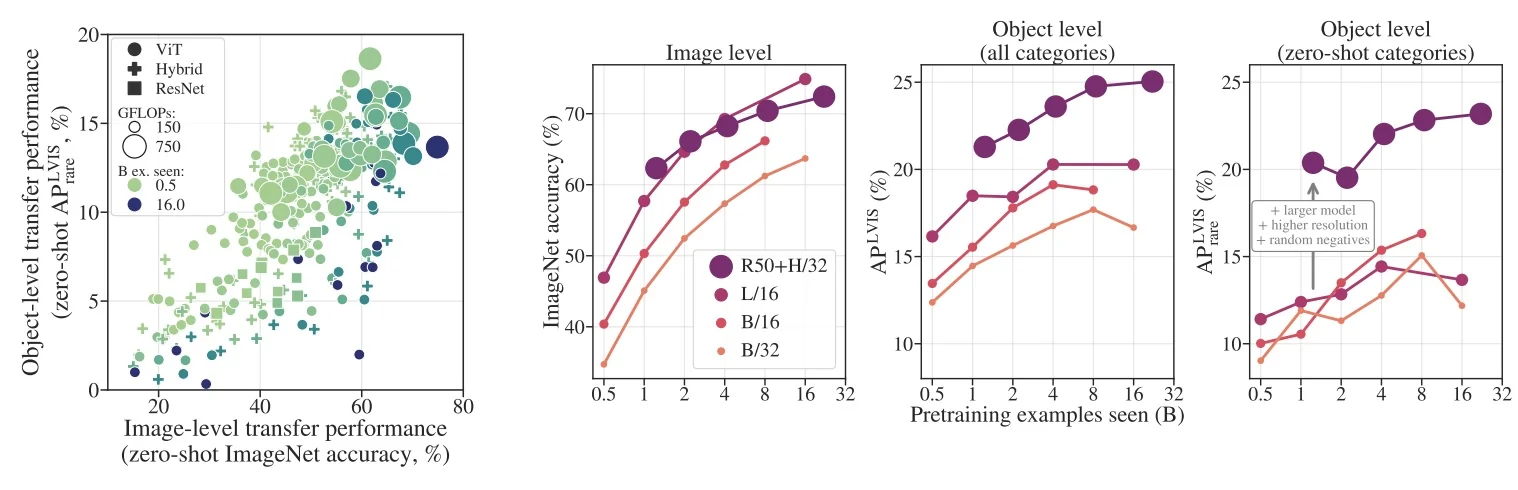

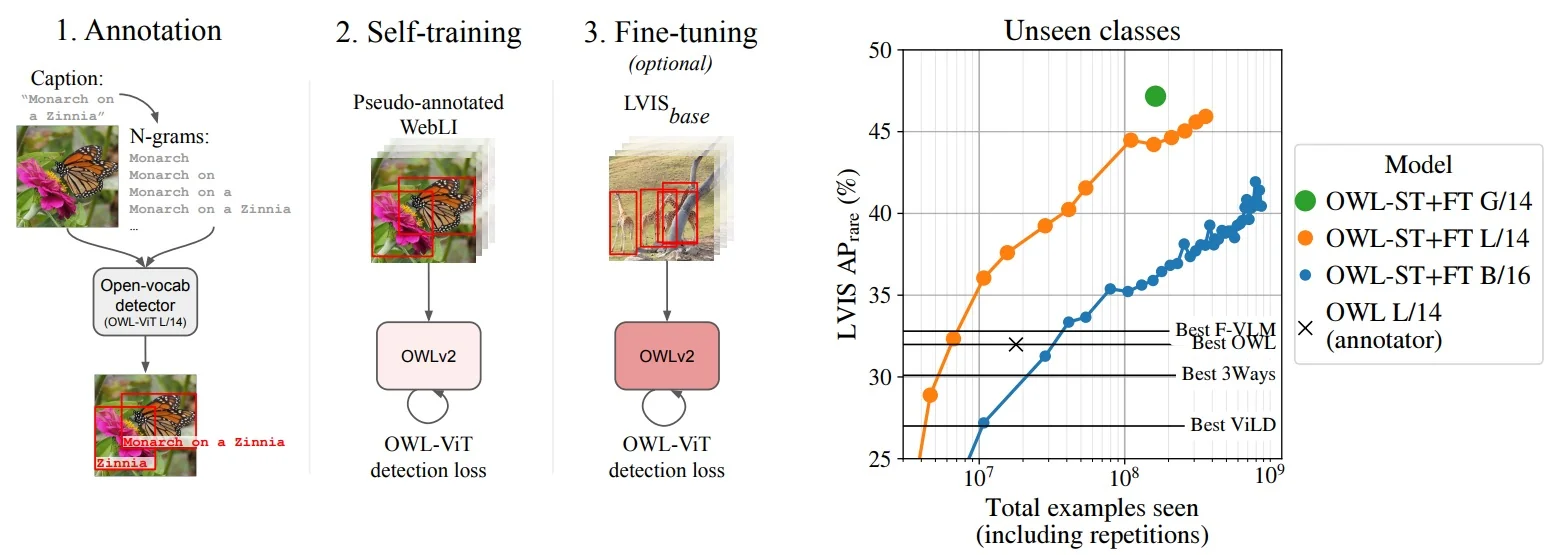

In the open-vocabulary setting briefly discussed in Chapter 13, many state-of-the-art systems build directly on these transformer and backbone advances: Grounding DINO [376], OWL-ViT and OWLv2 [433, 431], and YOLO-World [100] combine strong image encoders with text encoders to align region features with natural-language prompts. This allows detectors to move beyond a fixed label list and answer queries like “red umbrella” or “person holding a phone” in a zero-shot way.

We will study transformers, large vision backbones, and vision–language models in detail later in the book. For now, our goal is to master the classic CNN-based detectors—R-CNN, Fast R-CNN, Faster R-CNN, FPN-based two-stage models, and single-stage/anchor-free designs—since the principles they introduce are the foundation upon which these newer architectures are built.

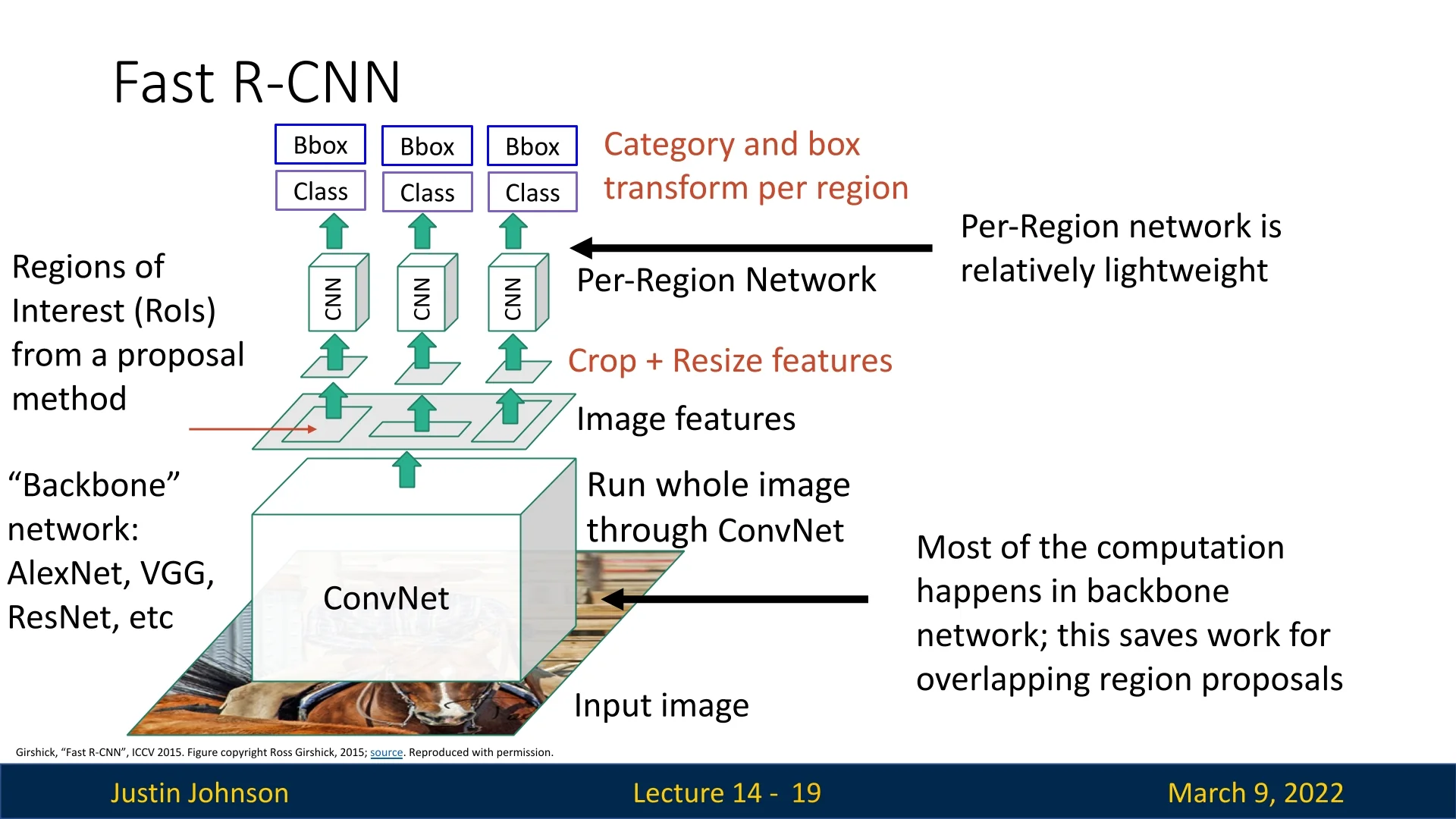

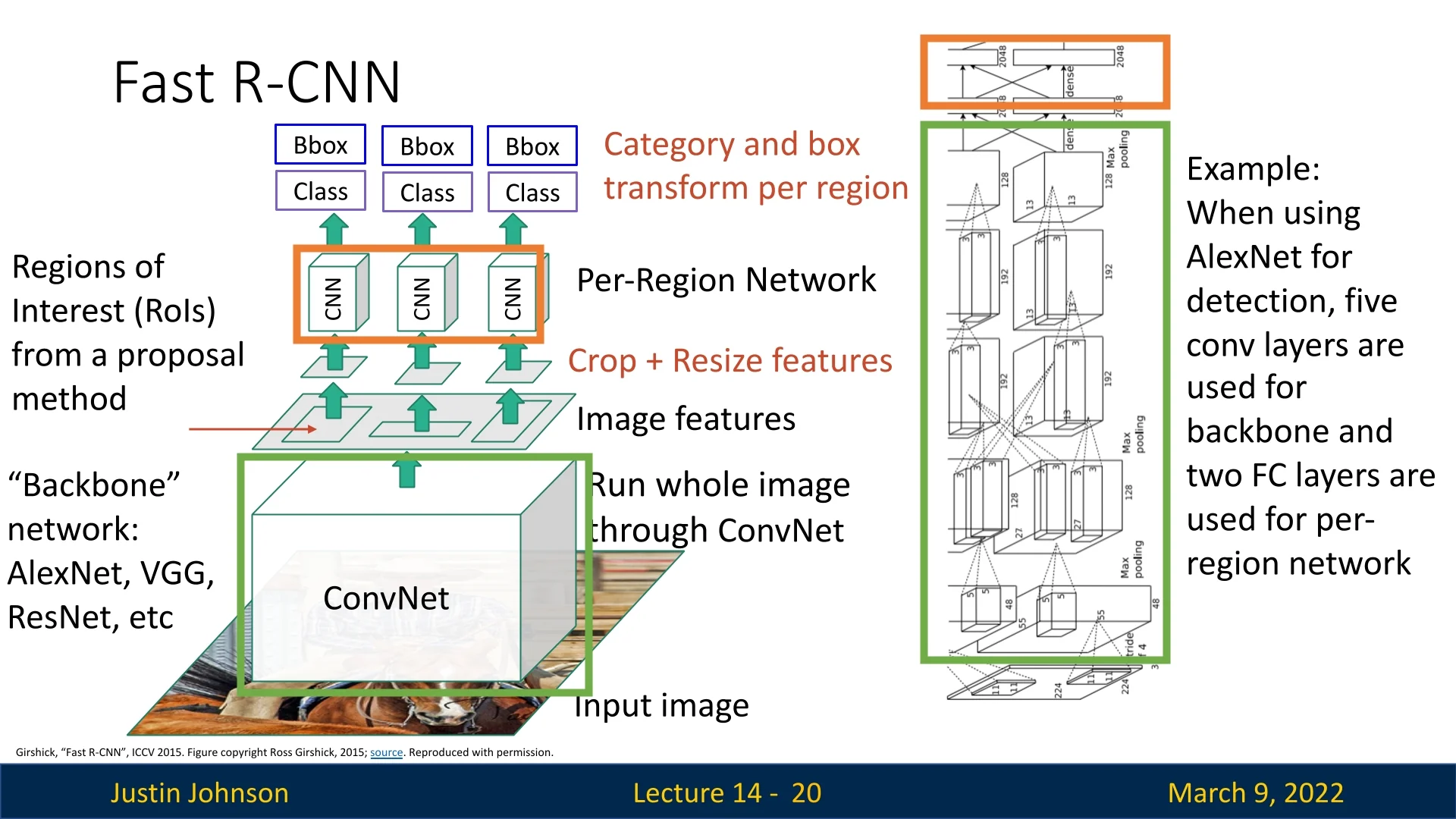

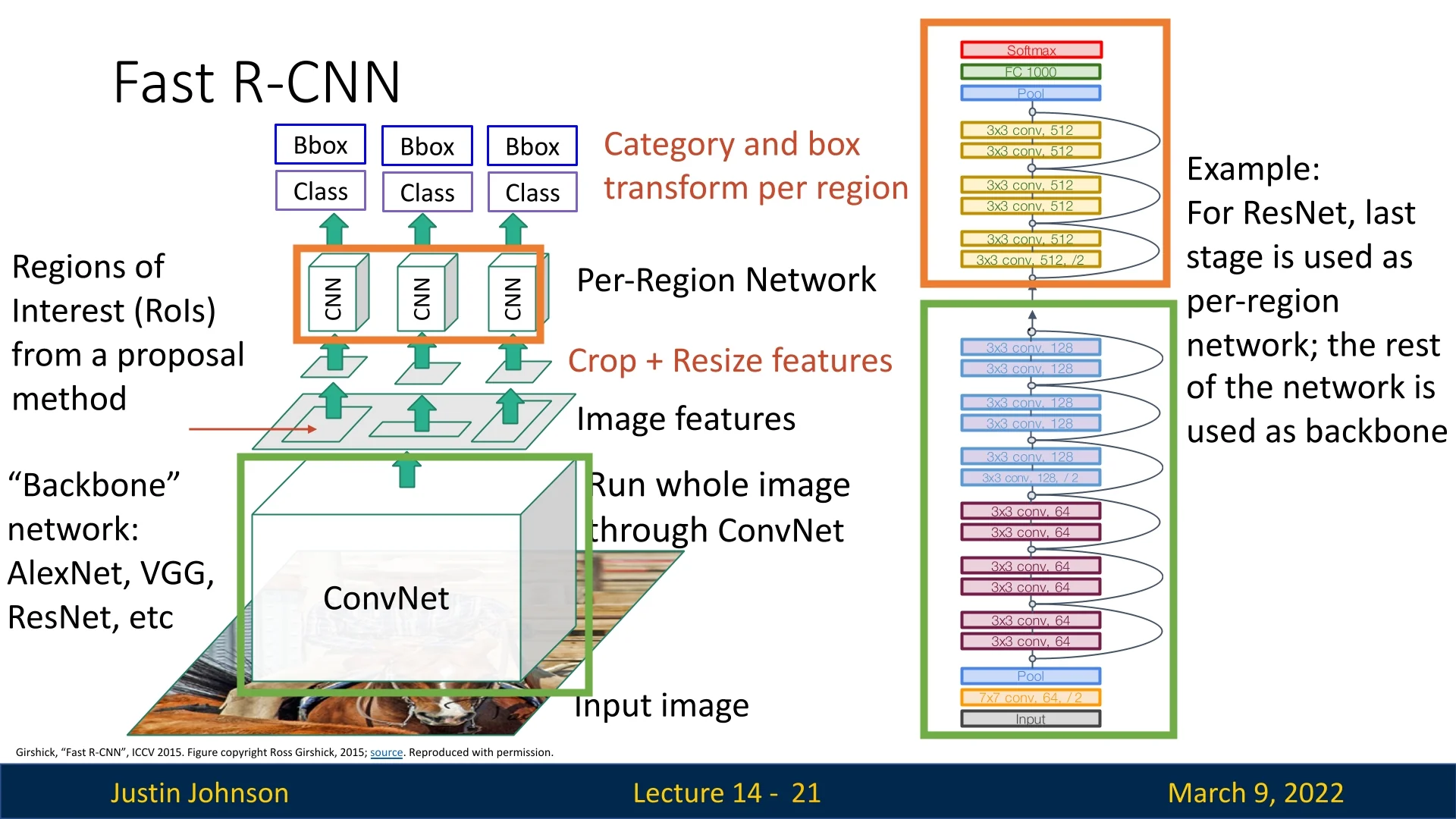

14.2 Fast R-CNN: Accelerating Object Detection

As running a CNN forward pass separately for each of the \(\sim 2000\) region proposals per image led to massive computational overhead, despite its performance, R-CNN was too slow for practical usage.

Fast R-CNN [175] was proposed as a major improvement, significantly reducing inference time while maintaining strong detection accuracy. By reusing shared feature maps instead of processing each region proposal independently, it eliminated redundant computations and improved efficiency.

14.2.1 Key Idea: Shared Feature Extraction

Instead of running a CNN separately for each proposal, Fast R-CNN applies a deep CNN once to the entire image.

It does so by extracting a shared feature representation. Then, Region of Interest (RoI) Pooling is used to extract features corresponding to each region proposal from this shared representation. A small per-region sub-network is then applied to each extracted region to Classify the region into an object category or background, and refine the bounding box using regression.

14.2.2 Using Fully Convolutional Deep Backbones for Feature Extraction

Fast R-CNN leverages deep CNNs to extract features from the entire image in one forward pass.

An interesting observation is that both approaches use a fully convolutional backbone.

This is deliberate, as a fully convolutional network produces a dense, spatially organized feature map in which each element corresponds directly to a specific location in the input image.

This spatial correspondence is critical for RoI pooling: it allows us to accurately map the coordinates of a region proposal (generated in the original image space) onto the feature map, so that the correct features can be “cropped out” and later pooled into a fixed-size representation.

In contrast, if the backbone ended with fully connected layers, the spatial arrangement would be lost because fully connected layers mix information from all locations. Without a maintained spatial structure, there would be no straightforward way to project a region proposal onto the feature map. Consequently, each proposal would have to be processed individually from the image itself—defeating the purpose of using a shared, efficient feature extractor.

14.2.3 Region of Interest (RoI) Pooling

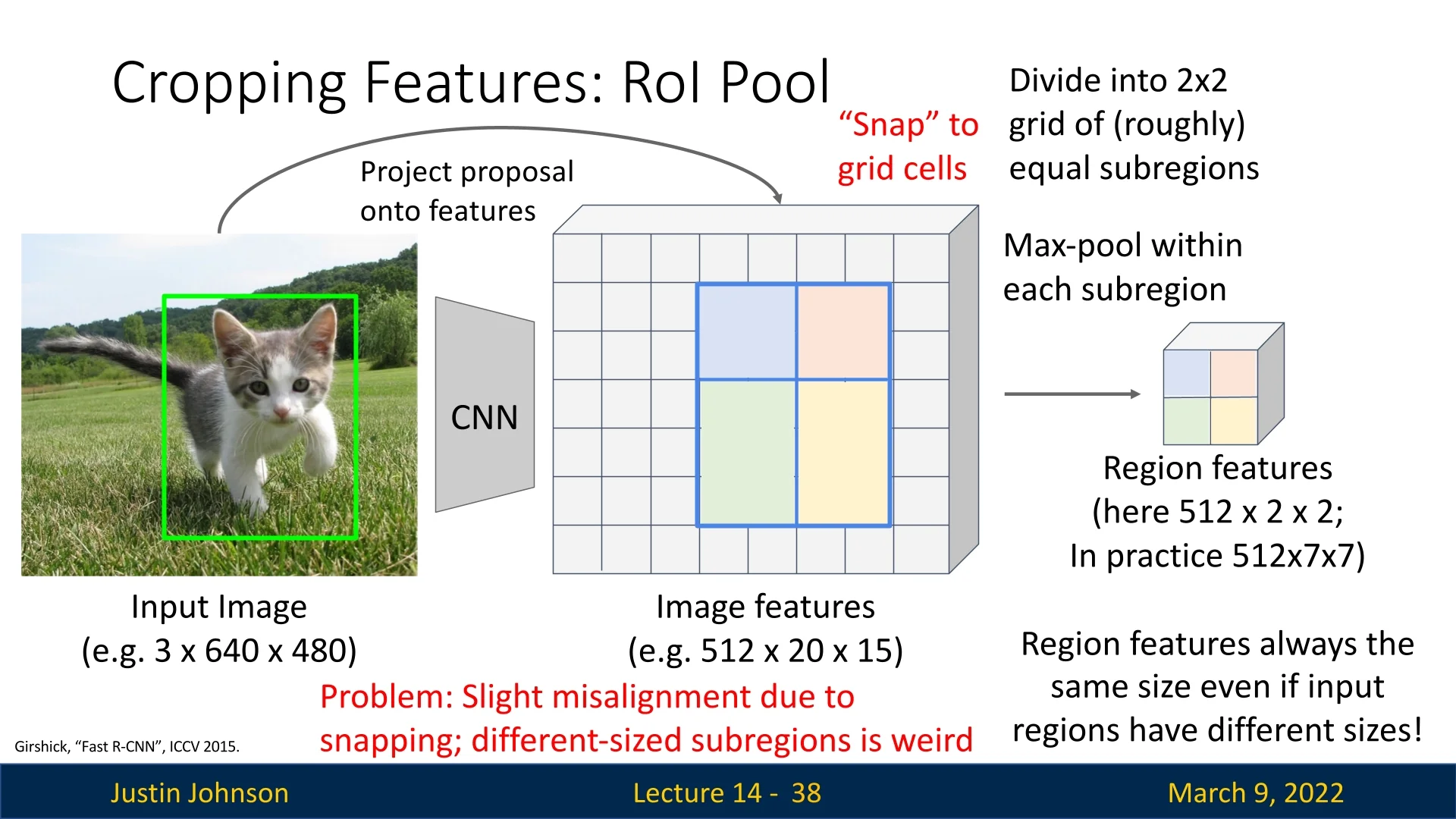

In Fast R-CNN, we aim to extract feature maps corresponding to each region proposal while ensuring that the process remains differentiable so we can backpropagate gradients through the backbone CNN. This challenge is addressed using Region of Interest (RoI) Pooling.

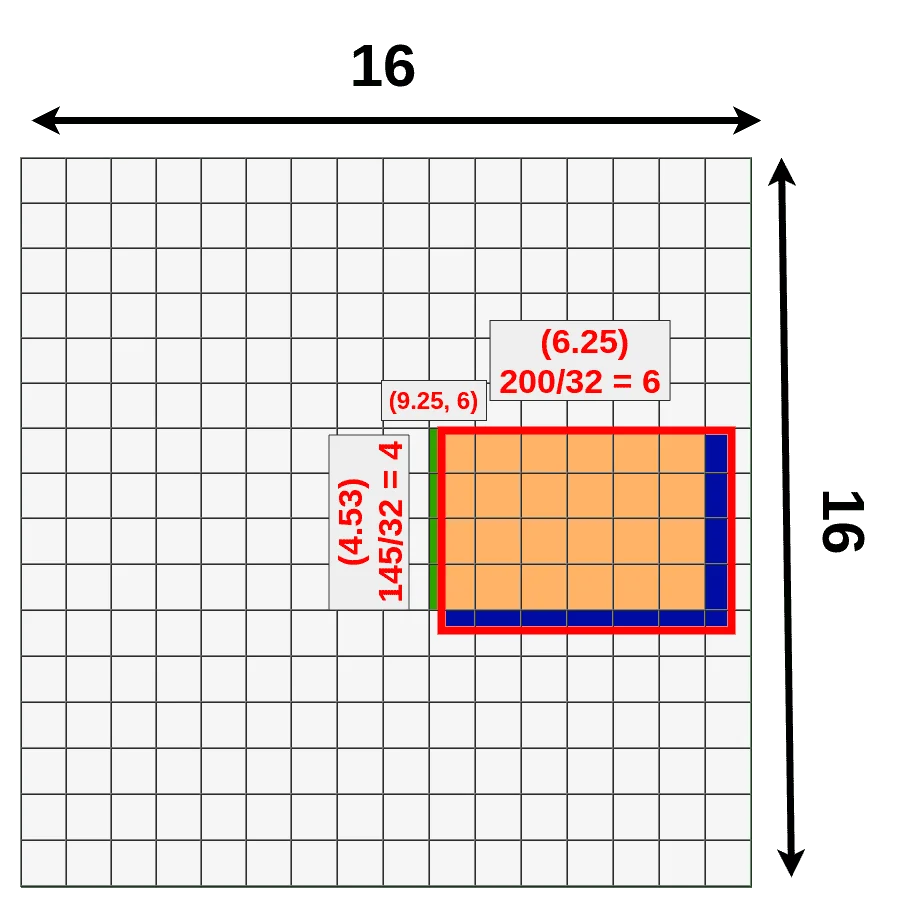

Mapping Region Proposals onto the Feature Map Region proposals—typically generated by methods such as selective search—are initially defined in the coordinate space of the original input image. However, because the backbone CNN downsamples the input by a factor \( k \) (e.g., \( k = 16 \)), these coordinates must be mapped onto the feature map. This transformation is given by:

\[ x' = \frac {x}{k}, \quad y' = \frac {y}{k}, \quad w' = \frac {w}{k}, \quad h' = \frac {h}{k} \]

where \( (x, y, w, h) \) represents the original coordinates and dimensions of the region proposal on the input image, and \( (x', y', w', h') \) represents the corresponding region on the feature map.

Since this division typically results in non-integer values (e.g., \( x' = 9.25 \)), the coordinates are quantized—usually by taking the floor function:

\[ x'' = \lfloor x' \rfloor , \quad y'' = \lfloor y' \rfloor , \quad w'' = \lfloor w' \rfloor , \quad h'' = \lfloor h' \rfloor \]

This snapping operation ensures that proposals align with the discrete grid of the feature map, making it possible to extract features corresponding to each proposal.

Dividing the Region into Fixed Bins Once the region proposal is mapped onto the feature map, the corresponding feature region is divided into a fixed number of bins. This binning ensures that all proposals—regardless of their original aspect ratio—are resized to a common spatial dimension. For example, if the target output size is \( 7 \times 7 \), the extracted region is divided into \( 7 \times 7 \) roughly equal spatial sub-regions.

Max Pooling within Each Bin For each bin, max pooling is applied across all the activations in that sub-region. This operation selects the maximum value within each bin, reducing variable-sized proposals to a uniform output shape while preserving strong feature responses. The output of RoI pooling for each proposal has a fixed spatial size, e.g., \( 7 \times 7 \times C \), where \( C \) is the number of channels in the feature map.

Summary: Key Steps in RoI Pooling

- 1.

- Scaling Region Proposals: The bounding box proposals are initially given in the coordinate space of the original image. Since the backbone CNN downsamples the input by a factor \( k \) (e.g., \( k=16 \)), the proposals must be scaled accordingly.

- 2.

- Extracting Feature Patches: The scaled bounding boxes are mapped to the corresponding feature map locations, ensuring alignment with the CNN’s output resolution.

- 3.

- Dividing into Sub-Regions: Each extracted feature patch is divided into a fixed grid of bins (e.g., \( 7 \times 7 \)), regardless of the original proposal size.

- 4.

- Max Pooling per Sub-Region: Within each bin, max pooling is applied to obtain a single representative feature value.

- 5.

- Fixed Output Size: The final output for each proposal is a tensor of shape(num_proposals, num_channels, output_size, output_size), making it suitable for downstream classification and bounding box regression.

The RoI Pooling operation can be implemented in PyTorch using a custom function that extracts fixed-size feature maps from region proposals. There is a nice implementation of [473] that follows the steps outlined earlier. If you want to understand how this method works in more detail, this is a good place to start.

Limitations of RoI Pooling A key limitation of RoI pooling is the quantization error introduced during the coordinate snapping process. Since features are assigned to discrete grid locations using floor division, minor localization errors may occur, reducing detection accuracy. This problem becomes more prominent in tasks requiring precise bounding box localization.

In addition, the fact that sub-regions are not always of the same size is also weird and may prove to be sub-optimal. Due to these problems, an improved approach called RoIAlign emerged. RoIAlign eliminates quantization errors by using bilinear interpolation instead of rounding coordinates to the nearest discrete pixel. In the next section, we will explore how RoIAlign refines feature extraction to improve object detection accuracy. Although not used in Faster R-CNN, it made its way to consequent papers like Mask R-CNN that we’ll cover later.

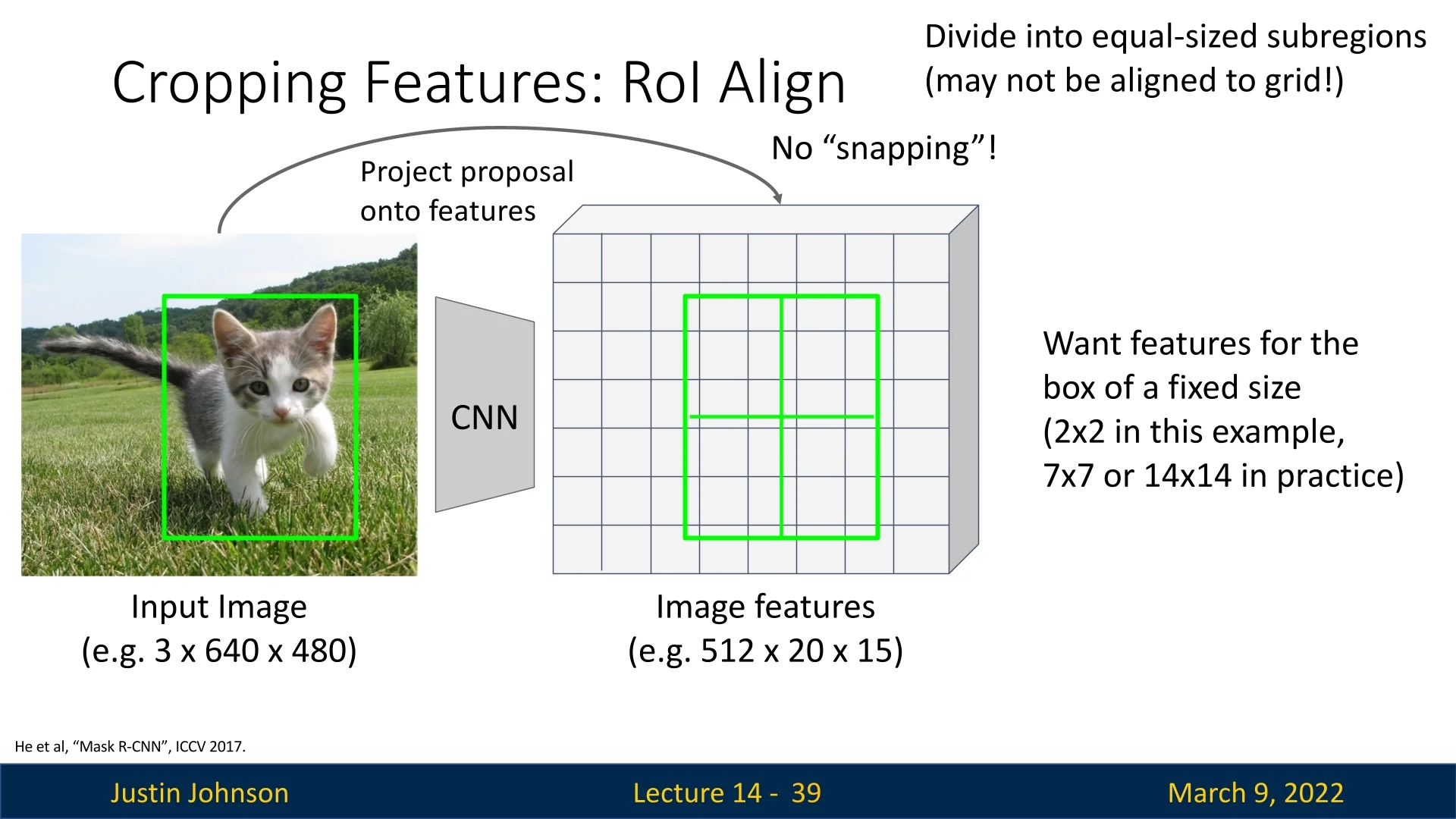

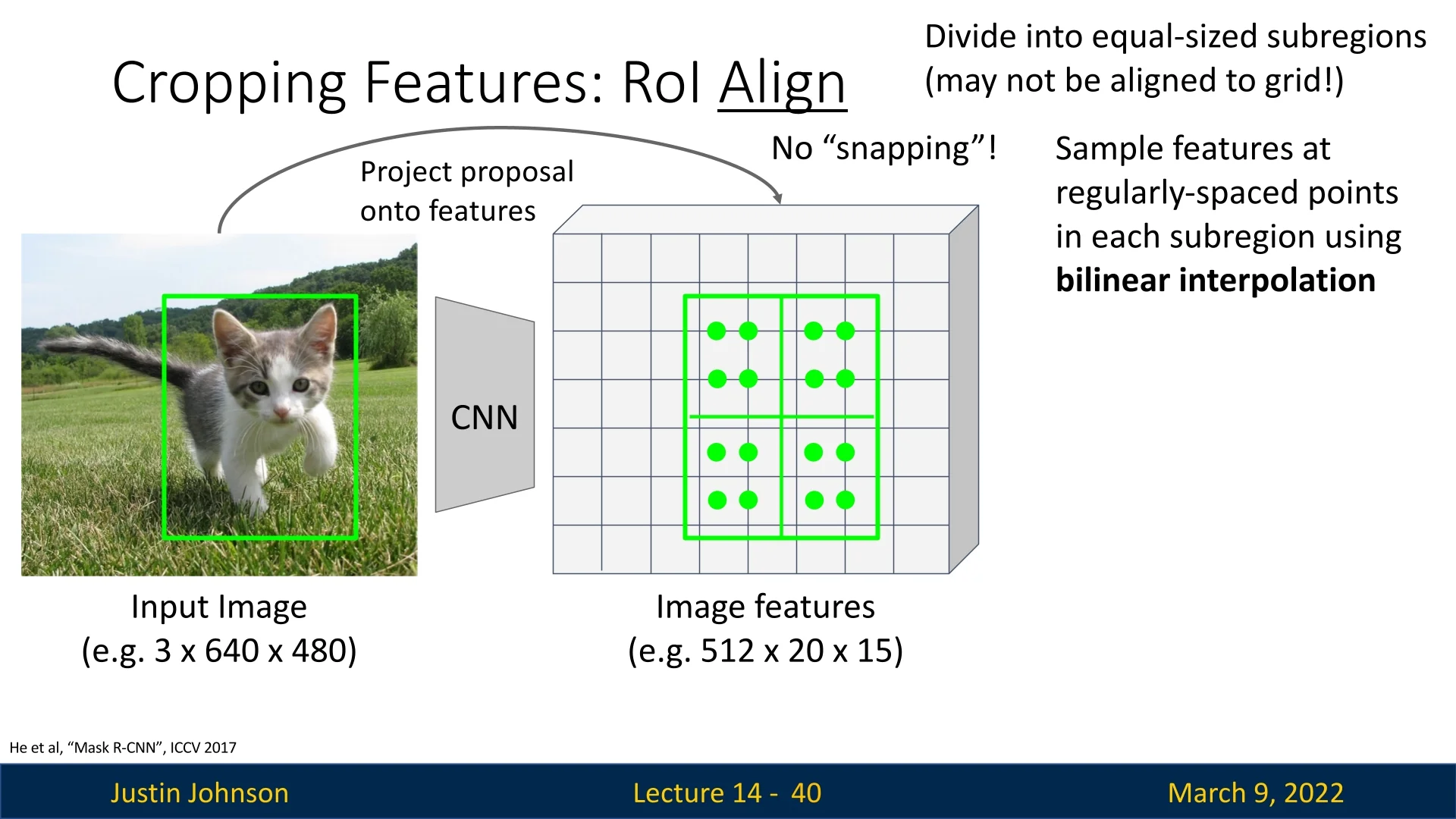

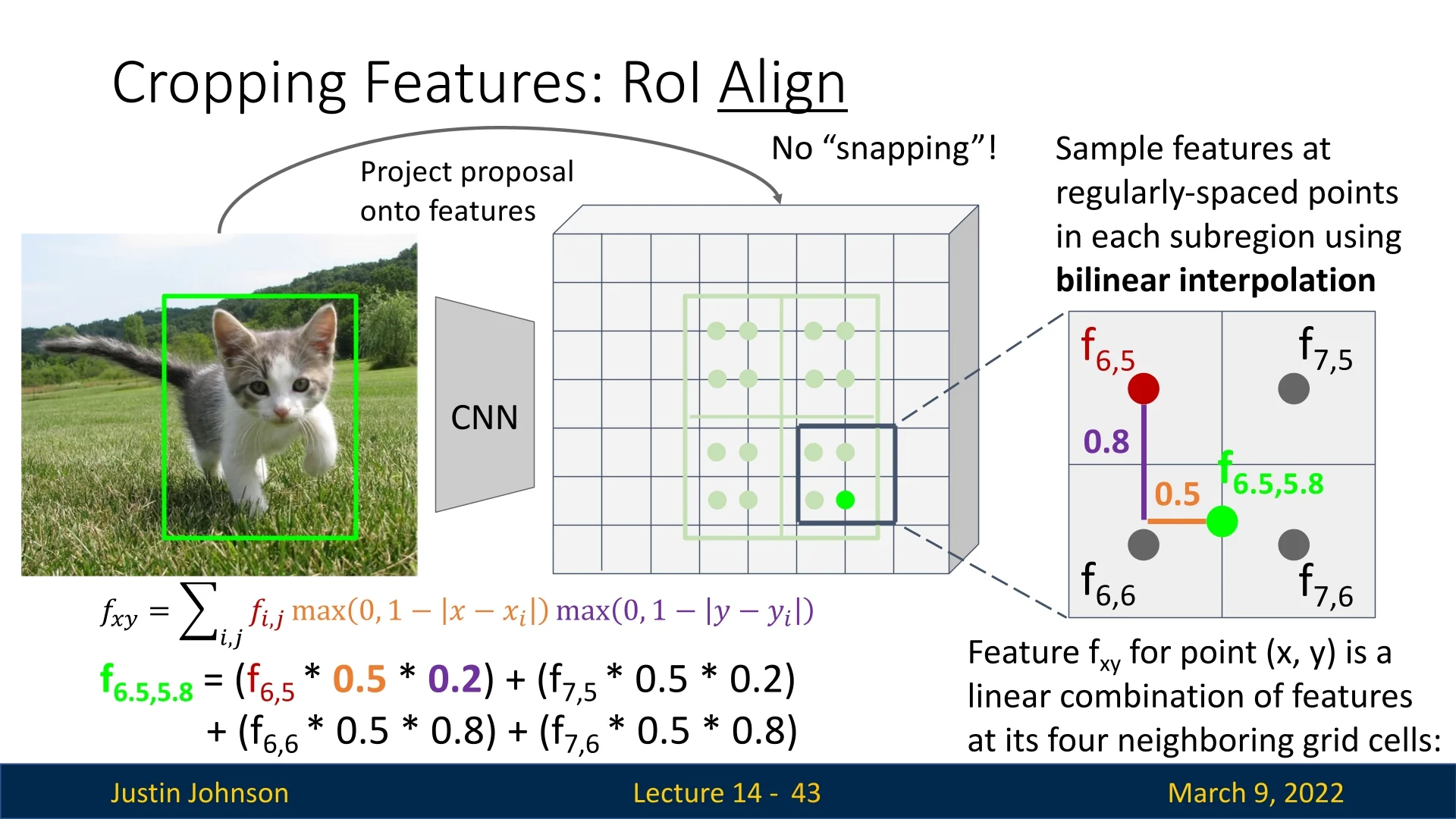

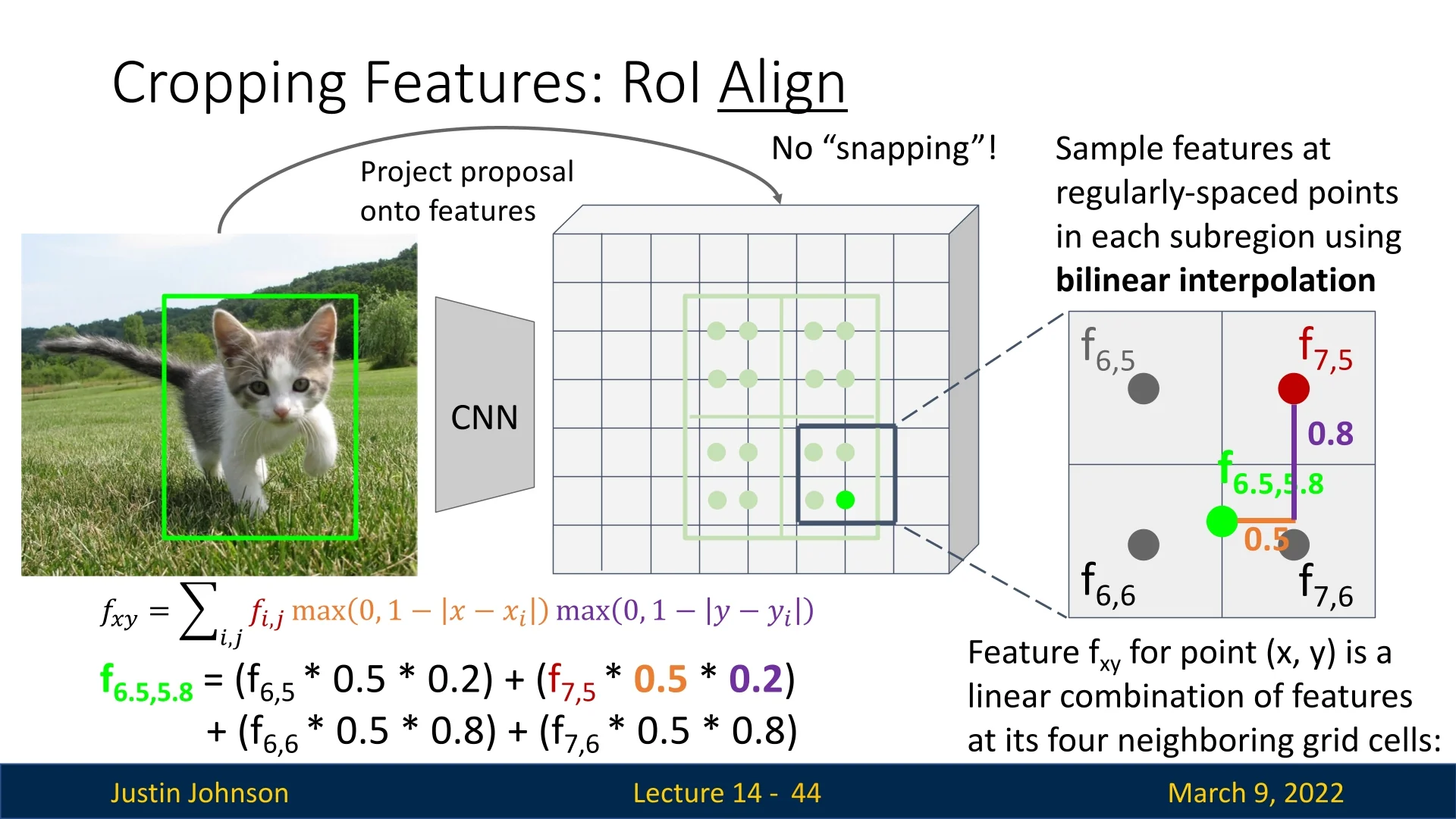

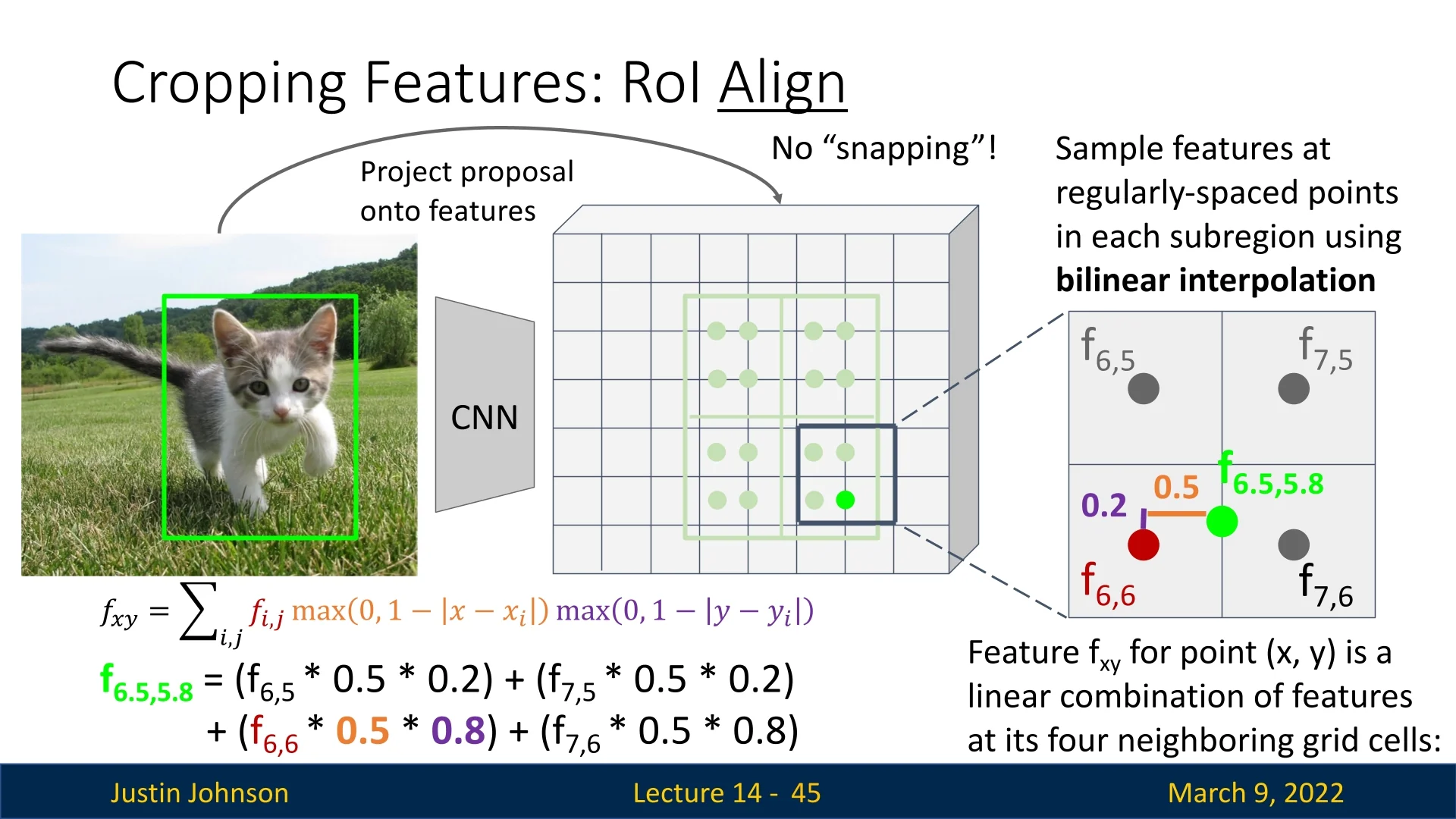

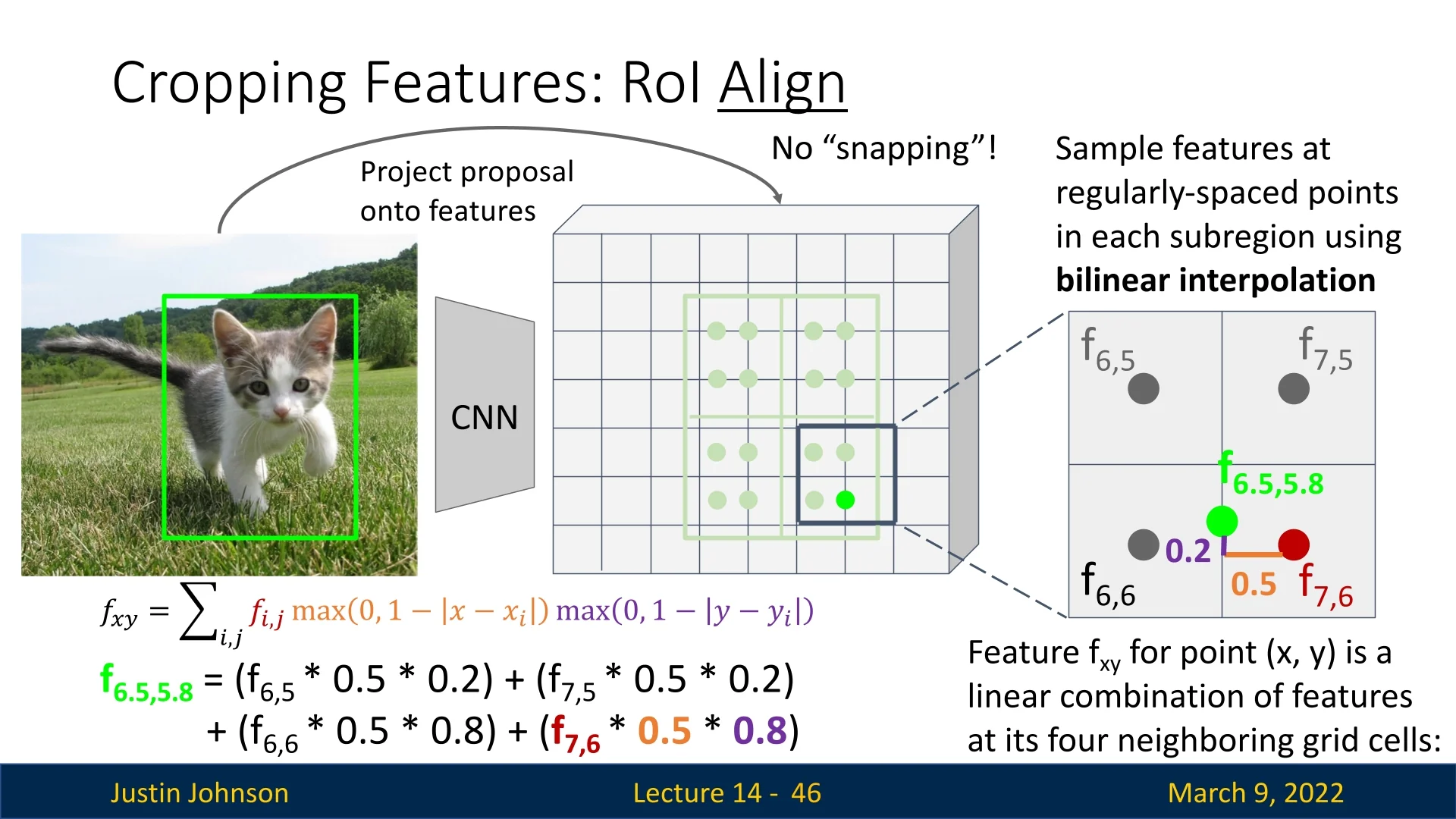

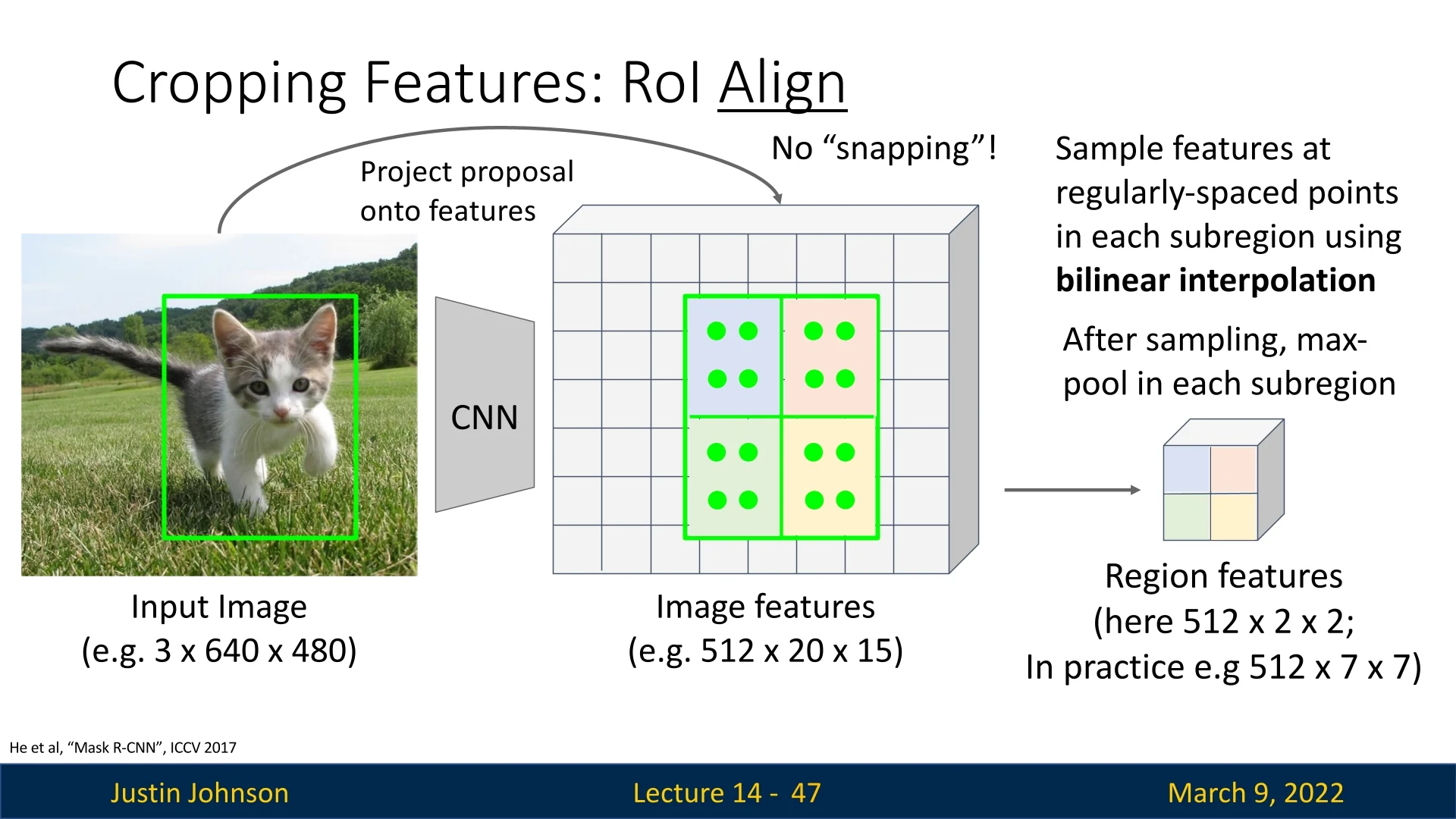

14.2.4 RoIAlign

In RoIAlign we avoid any quantization (rounding) of the coordinates. Instead, we sample the feature map using bilinear interpolation to obtain sub-pixel accuracy and preserve alignment. The idea is to compute a linear combination of feature values based on their Euclidean distance to the sampling point. By doing so, each sub-region in the region of interest contributes a weighted average of the feature map’s values, thus preventing misalignments introduced by discrete rounding.

RoIAlign: A Visual Example

To further understand how RoIAlign works in practice, we follow a step-by-step example inspired by Justin’s lecture and [473], of which the code snippets are taken (with extra documentation I added to make it a bit more clear). This example applies RoIAlign to a region proposal of a cat image projected onto the activation/feature map. For simplicity, we use an output size of \(2 \times 2\), meaning the proposal is divided into four equal-sized sub-regions (bins), and we extract a single representative value per bin. In practice, output sizes of \(7 \times 7, 14 \times 14\) are more reasonable and common.

Step 1: Projection of Region Proposal onto the Feature Map First, we map the region proposal onto the feature map without quantization. The projected region is divided into \(2 \times 2\) bins.

Step 2: Selecting Interpolation Points in Each Bin In RoIAlign, each bin within a region proposal is divided into regularly spaced sampling points to avoid quantization errors. Instead of snapping to the nearest discrete grid like in RoI Pooling, RoIAlign selects four interpolation points per bin to estimate the feature value using bilinear interpolation.

For each bin, four sample points are computed as follows:

- \( (x_1, y_1) \) – Top-left interpolation point

- \( (x_1, y_2) \) – Bottom-left interpolation point

- \( (x_2, y_1) \) – Top-right interpolation point

- \( (x_2, y_2) \) – Bottom-right interpolation point

As reminder, here is the part of the code in the RoIAlign method, used to compute the points to interpolate within each region of the projected proposal.

for i in range(self.output_size):

for j in range(self.output_size):

x_bin_strt = i * w_stride + xp0 # Bin’s top-left x coordinate

y_bin_strt = j * h_stride + yp0 # Bin’s top-left y coordinate

# Generate 4 points for interpolation (no rounding!)

x1 = torch.Tensor([x_bin_strt + 0.25 * w_stride]) # Quarter into the bin

x2 = torch.Tensor([x_bin_strt + 0.75 * w_stride]) # Three-quarters inside

y1 = torch.Tensor([y_bin_strt + 0.25 * h_stride]) # # Quarter into the bin

y2 = torch.Tensor([y_bin_strt + 0.75 * h_stride]) # Three-quarters inside

# Bilinear interpolation will be performed at (x1, y1), (x1, y2), (x2,

# y1), and (x2, y2), and these values will be used to compute the final

# bin output for the per-region network.For each bin (sub-region), two sample points are taken along both the \(x\)-axis and \(y\)-axis, creating a total of \(2 \times 2 = 4\) sample points. The interpolation points are systematically selected as:

\[ \{x_1, x_2\} \times \{y_1, y_2\} \]

ensuring comprehensive coverage within the bin.

Why Choose 0.25 and 0.75 for Sampling? Instead of selecting points at the exact center of each bin (\(0.5\)) or at its edges (\(0.0\) and \(1.0\)), RoIAlign samples points at \(0.25\) and \(0.75\) of the bin’s width and height. This design choice serves several purposes:

- Avoiding boundary artifacts: Sampling at \(0.0\) (bin edges) can cause rounding errors or unexpected shifts due to floating-point imprecision. Sampling at \(0.25\) and \(0.75\) keeps the points well inside the bin, ensuring they stay within the intended spatial region.

- Capturing feature variation: Sampling at just one location (e.g., the center at \(0.5\)) might miss important variations within the bin. By selecting two points per axis, we better approximate the feature distribution in that region.

- Consistent coverage: This approach systematically captures more representative “average” features, reducing the impact of noise and ensuring smooth gradient flow during backpropagation.

While RoIAlign typically uses a \(2 \times 2\) grid of sample points per bin, some implementations allow configurable sampling ratios, such as \(3 \times 3\) or higher, to improve approximation accuracy at the cost of additional computation.

By eliminating quantization artifacts and ensuring precise feature extraction, this step significantly enhances the quality of extracted region features, making RoIAlign an essential improvement over RoI Pooling.

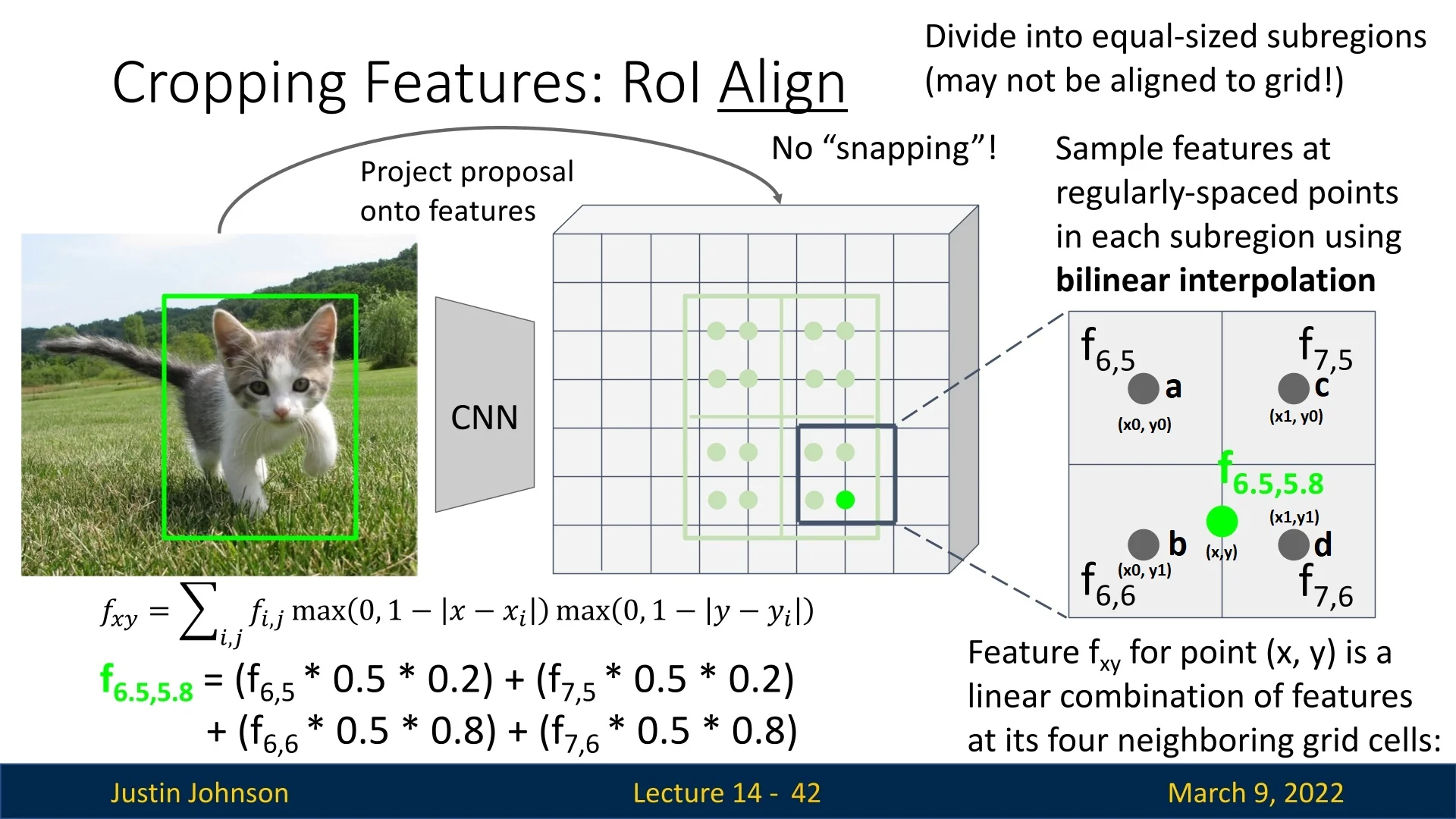

Step 3: Mapping Sampled Points onto the Feature Grid Each of the four sampled points per bin lies within the continuous feature map, requiring us to determine its surrounding discrete grid points for bilinear interpolation. Given a sampled point \((x, y)\), it is enclosed by four neighboring integer grid points:

- \( a: (x_0, y_0) \) – Top-left corner

- \( b: (x_0, y_1) \) – Bottom-left corner

- \( c: (x_1, y_0) \) – Top-right corner

- \( d: (x_1, y_1) \) – Bottom-right corner

In our example, in the bottom-right bin, we consider a sampled point at \((x_2, y_2) = (6.5, 5.8)\) that is also the bottom-right point within the bin. The nearest integer grid points that enclose it are:

\[ a=(x_0 = 6, y_0 = 5), \quad b=(x_0 = 6, y_1 = 6), \quad c=(x_1 = 7, y_0 = 5), \quad d=(x_1 = 7, y_1 = 6). \]

These four points are used for interpolation, ensuring that each sampled feature value is derived from its surrounding grid points rather than being snapped to the nearest one.

To determine these enclosing grid points programmatically, we perform the following computations:

# Find the integer corners surrounding (x, y)

x0 = torch.floor(x).type(torch.cuda.LongTensor)

x1 = x0 + 1

y0 = torch.floor(y).type(torch.cuda.LongTensor)

y1 = y0 + 1

# Clamp these coordinates to the image boundary to avoid out-of-range indexing

x0 = torch.clamp(x0, 0, img.shape[1] - 1)

x1 = torch.clamp(x1, 0, img.shape[1] - 1)

y0 = torch.clamp(y0, 0, img.shape[0] - 1)

y1 = torch.clamp(y1, 0, img.shape[0] - 1)

# Extract feature values at the four surrounding grid points

Ia = img[y0, x0] # Top-left corner

Ib = img[y1, x0] # Bottom-left corner

Ic = img[y0, x1] # Top-right corner

Id = img[y1, x1] # Bottom-right cornerThese four feature values \((I_a, I_b, I_c, I_d)\) serve as the basis for bilinear interpolation. Instead of directly snapping \((x, y)\) to the nearest feature grid location, we compute a weighted average of these values, using their relative distances as interpolation weights.

By mapping sampled points onto discrete grid locations in this manner, RoIAlign ensures that every proposal maintains precise alignment with the backbone’s feature map, preserving sub-pixel accuracy and avoiding misalignment errors caused by quantization.

Step 4: Computing Bilinear Interpolation Weights Once the four nearest integer grid points for a sampled point \((x,y)\) have been identified, we compute weights that determine each corner’s contribution to the interpolated value. These weights are based on the relative distances between \((x,y)\) and the four grid points.

Normalization Constant and Its Interpretation The normalization constant is given by \[ \mbox{norm_const} = \frac {1}{(x_1 - x_0)(y_1 - y_0)}, \] which is the inverse of the area of the rectangle formed by the grid points \((x_0,y_0)\), \((x_1,y_0)\), \((x_0,y_1)\), and \((x_1,y_1)\). In many cases, including our example, this rectangle is a unit square (i.e., \(x_1 - x_0 = 1\) and \(y_1 - y_0 = 1\)), so the normalization constant is 1. This constant ensures that the computed weights form a convex combination that sums to 1.

Weight Computation for Each Corner For a sampled point \((x,y) = (6.5, 5.8)\), assume the four surrounding grid points are: \[ (x_0,y_0) = (6,5), \quad (x_1,y_0) = (7,5), \quad (x_0,y_1) = (6,6), \quad (x_1,y_1) = (7,6). \] We compute the distances: \[ x_1 - x = 7 - 6.5 = 0.5, \quad x - x_0 = 6.5 - 6 = 0.5, \] \[ y_1 - y = 6 - 5.8 = 0.2, \quad y - y_0 = 5.8 - 5 = 0.8. \] The weight for each grid point is the product of the fractional distances along the x and y axes, meaning, each weight is determined by how far the sampled point is from a particular corner, considering both x and y distances. The horizontal and vertical contributions are combined as: - \((x_1 - x) / (x_1 - x_0)\) → Fraction of the width from \((x, y)\) to the right boundary. - \((x - x_0) / (x_1 - x_0)\) → Fraction from \((x, y)\) to the left boundary. - \((y_1 - y) / (y_1 - y_0)\) → Fraction of the height from \((x, y)\) to the bottom boundary. - \((y - y_0) / (y_1 - y_0)\) → Fraction from \((x, y)\) to the top boundary.

Therefore, for the top-left corner (denoted \(w_a\)), the weight is given by: \[ w_a = (x_1 - x) \cdot (y_1 - y) = 0.5 \times 0.2 = 0.1. \] Similarly, for the top-right corner (denoted \(w_c\)): \[ w_c = (x - x_0) \cdot (y_1 - y) = 0.5 \times 0.2 = 0.1. \] For the bottom-left corner (denoted \(w_b\)): \[ w_b = (x_1 - x) \cdot (y - y_0) = 0.5 \times 0.8 = 0.4, \] and for the bottom-right corner (denoted \(w_d\)): \[ w_d = (x - x_0) \cdot (y - y_0) = 0.5 \times 0.8 = 0.4. \] Thus, the weights satisfy \[ w_a + w_b + w_c + w_d = 0.1 + 0.4 + 0.1 + 0.4 = 1.0. \]

Step 5: Computing the Interpolated Feature Value Once the interpolation weights have been determined, we compute the interpolated feature value at \((x, y)\) as a weighted sum of the four surrounding feature grid values:

\[ f_{xy} = w_a f_{x_0 y_0} + w_b f_{x_0 y_1} + w_c f_{x_1 y_0} + w_d f_{x_1 y_1} \]

Each weight determines the contribution of the corresponding grid point to the interpolated value. Since closer grid points have higher weights, they exert more influence over the final value than those further away.

Example Computation For the sampled point \((x,y) = (6.5, 5.8)\), using previously computed weights: \[ w_a = 0.1, \quad w_b = 0.4, \quad w_c = 0.1, \quad w_d = 0.4 \]

and the corresponding feature values from the activation map:

\[ I_a = f_{6,5}, \quad I_b = f_{6,6}, \quad I_c = f_{7,5}, \quad I_d = f_{7,6} \]

we compute the interpolated feature value as:

\[ f_{6.5,5.8} = (0.1 \times f_{6,5}) + (0.4 \times f_{6,6}) + (0.1 \times f_{7,5}) + (0.4 \times f_{7,6}) \]

Step 6: Aggregating Interpolated Values After computing the interpolated feature values for all sampled points, we aggregate them using either:

- Average pooling: The final value is the mean of all interpolated feature values.

- Max pooling: The final value is the maximum of all interpolated values.

In Justin’s example, max pooling is used: \[ \mbox{bin value} = \max (v_1, v_2, v_3, v_4) \]

Final Output After iterating over all bins, the final RoI feature map is constructed, with each bin containing an aggregated value from bilinear interpolation. The per-proposal network then uses this structured feature representation for classification and bounding-box regression.

- RoIAlign eliminates the quantization error of RoI Pooling by leveraging bilinear interpolation.

- The interpolation process ensures precise feature extraction, leading to improved localization accuracy.

- The final feature map maintains a fixed size per RoI, making it compatible with subsequent per-region classifiers and regressors.

Hence, RoIAlign is a core component of modern architectures used for detection and segmentation like Mask R-CNN.

RoIAlign Important Implementation Parts in PyTorch Following the implementation of [473], here are the important code snippets that illustrate how RoIAlign works, helping to see how the process looks like from start to finish.

def _roi_align(self, features, scaled_proposal):

"""Given feature layers and scaled proposals return bilinear interpolated

points in feature layer

Args:

features (torch.Tensor): Tensor of shape <channels x height x width>

scaled_proposal (list of torch.Tensor): Each tensor is a bbox by which we

will extract features from features Tensor

"""

_, num_channels, h, w = features.shape

# (xp0, yp0) = top-left corner of projected proposal, (xp1, yp1) = bottom-right corner.

xp0, yp0, xp1, yp1 = scaled_proposal

p_width = xp1 - xp0

p_height = yp1 - yp0

’’’

If we want to output a nxn tensor to the per-proposal network, then output_size = n.

The number of sub-regions we’ll produce, like in RoIPool, will be nxn as well.

The height and width of each sub-region will be equal, as the regions are now of exactly the same size,

but crucially we no longer snap to integer boundaries.

Each sub-region’s representative value will be a linear combination of the pixel values

that this sub-region covers(via bilinear interpolation).

’’’

w_stride = p_width / self.output_size # The width of each sub-region

h_stride = p_height / self.output_size # The height of each sub-region

interp_features = torch.zeros((num_channels, self.output_size, self.output_size))

for i in range(self.output_size):

for j in range(self.output_size):

# top-left x coordinate of the i-th sub-region

x_bin_strt = i * w_stride + xp0

# top-left y coordinate of the j-th sub-region

y_bin_strt = j * h_stride + yp0

# generate 4 points for interpolation (no rounding!)

x1 = torch.Tensor([x_bin_strt + 0.25*w_stride]) # quarter in the bin (x-axis)

x2 = torch.Tensor([x_bin_strt + 0.75*w_stride]) # three-quarters in the bin (x-axis)

y1 = torch.Tensor([y_bin_strt + 0.25*h_stride]) # quarter in the bin (y-axis)

y2 = torch.Tensor([y_bin_strt + 0.75*h_stride]) # three-quarters in the bin (y-axis)

’’’

We sample 2 points along x(0.25 and 0.75 of the bin width)

and 2 points along y(0.25 and 0.75 of the bin height).

This yields 2 x 2 = 4 sample points per bin.

Why at 0.25 and 0.75?

1) Avoid boundaries: Sampling at 0 or 1 might cause rounding/boundary issues.

2) Capture variation: Multiple sample points per bin help represent

the internal structure better than a single center point.

3) Consistent coverage: 0.25 and 0.75 systematically offer an even "spread"

in each dimension, approximating the average effectively.

’’’

for c in range(num_channels):

# features[0, c] is the single-channel feature map for channel c

img = features[0, c]

v1 = bilinear_interpolate(img, x1, y1)

v2 = bilinear_interpolate(img, x1, y2)

v3 = bilinear_interpolate(img, x2, y1)

v4 = bilinear_interpolate(img, x2, y2)

’’’

v1, v2, v3, v4 are the bilinear-interpolated values at the four sample points.

We average these 4 values to get a single value for bin(i, j) and channel c.

Note: In some cases, one might take max instead of average

(mimicking max pooling). This is what Justin shows in the lecture. Hence, he takes max(v1, v2, v3, v4) instead.

’’’

interp_features[c, j, i] = (v1 + v2 + v3 + v4) / 4

return interp_featuresWe now understand the RoIAlign high-level flow. Next, let us examine how bilinear interpolation works for the four regularly sampled points inside each bin, of which we’ll compute the output bin value for the per-proposal network later.

def bilinear_interpolate(img, x, y):

’’’ We are given a point(x, y) that might not be a pixel coordinate,

and we want to interpolate its feature value from the surrounding pixels.

’’’

# find the integer corners that surround (x, y)

x0 = torch.floor(x).type(torch.cuda.LongTensor)

x1 = x0 + 1

y0 = torch.floor(y).type(torch.cuda.LongTensor)

y1 = y0 + 1

# clamp these coordinates to the image boundary to avoid indexing out of range

x0 = torch.clamp(x0, 0, img.shape[1] - 1)

x1 = torch.clamp(x1, 0, img.shape[1] - 1)

y0 = torch.clamp(y0, 0, img.shape[0] - 1)

y1 = torch.clamp(y1, 0, img.shape[0] - 1)

# top-left, bottom-left, top-right, bottom-right corner values

Ia = img[y0, x0]

Ib = img[y1, x0]

Ic = img[y0, x1]

Id = img[y1, x1]

’’’

Next, we compute the weights for each corner. The idea:

- (x1 - x) -> how far we are from the right edge in the x direction

- (x - x0) -> how far we are from the left edge in the x direction

- (y1 - y) -> how far we are from the bottom edge in the y direction

- (y - y0) -> how far we are from the top edge in the y direction

We multiply these "partial distances" and then normalize by the total "area"

((x1 - x0)*(y1 - y0)) so that wa+wb+wc+wd = 1.

’’’

norm_const = 1 / ((x1.type(torch.float32) - x0.type(torch.float32)) *

(y1.type(torch.float32) - y0.type(torch.float32)))

wa = (x1.type(torch.float32) - x) * (y1.type(torch.float32) - y) * norm_const

wb = (x1.type(torch.float32) - x) * (y - y0.type(torch.float32)) * norm_const

wc = (x - x0.type(torch.float32)) * (y1.type(torch.float32) - y) * norm_const

wd = (x - x0.type(torch.float32)) * (y - y0.type(torch.float32)) * norm_const

# final bilinear interpolation: weighted sum of the four corners

return torch.t(torch.t(Ia) * wa) + torch.t(torch.t(Ib) * wb) + \

torch.t(torch.t(Ic) * wc) + torch.t(torch.t(Id) * wd)14.3 Faster R-CNN: Faster Proposals Using RPNs

14.3.1 Fast R-CNN Bottleneck: Region Proposal Computation

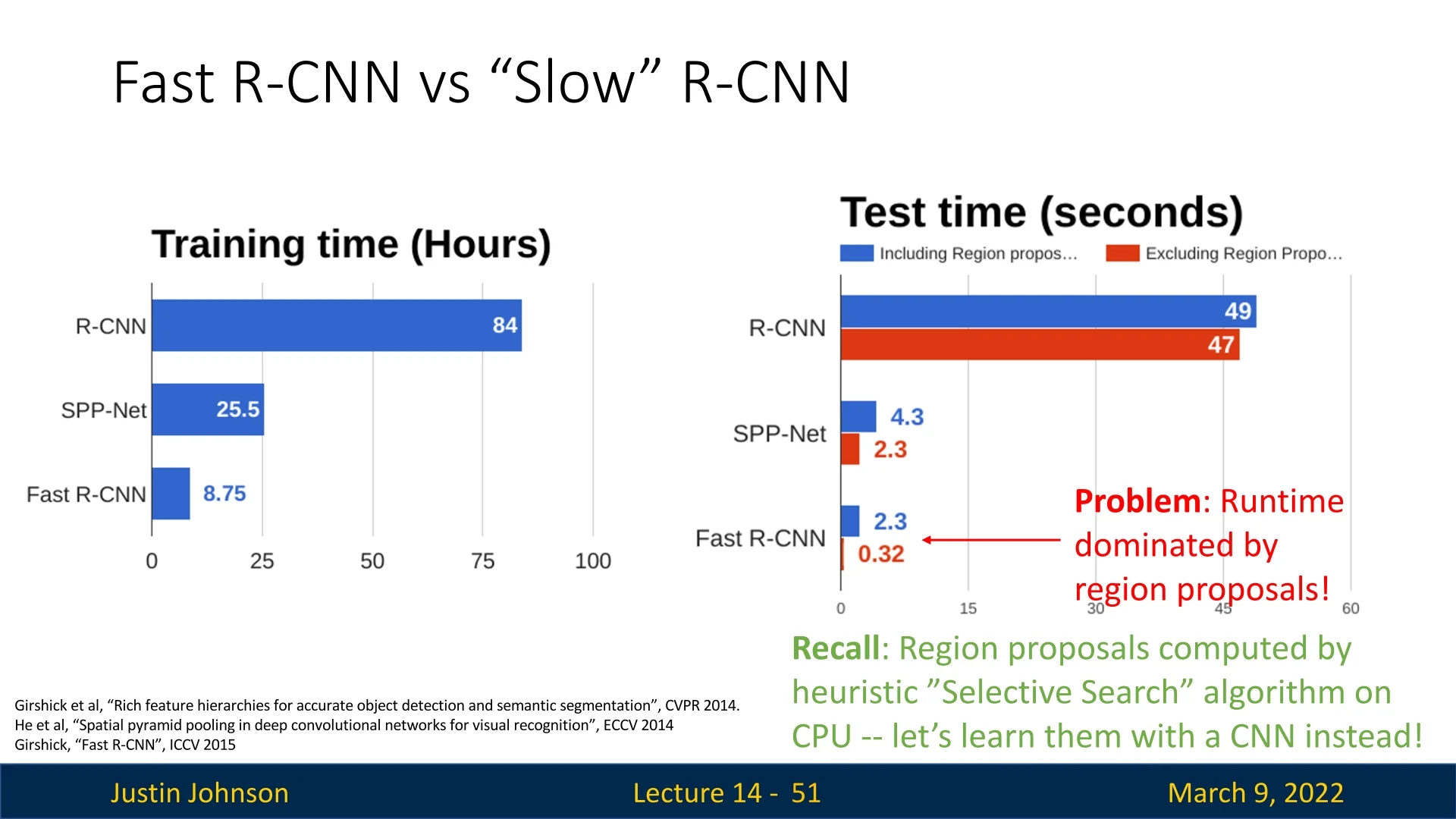

Although Fast R-CNN optimized the detection pipeline, the slowest component remained the region proposal generation. The external algorithm used, such as Selective Search, was still running on the CPU, making it a major bottleneck.

As shown in Figure 14.14, even though feature extraction and classification were now efficient, generating proposals using heuristic-based methods still consumed a significant portion of the runtime.

14.3.2 Towards Faster Region Proposals: Learning Proposals with CNNs

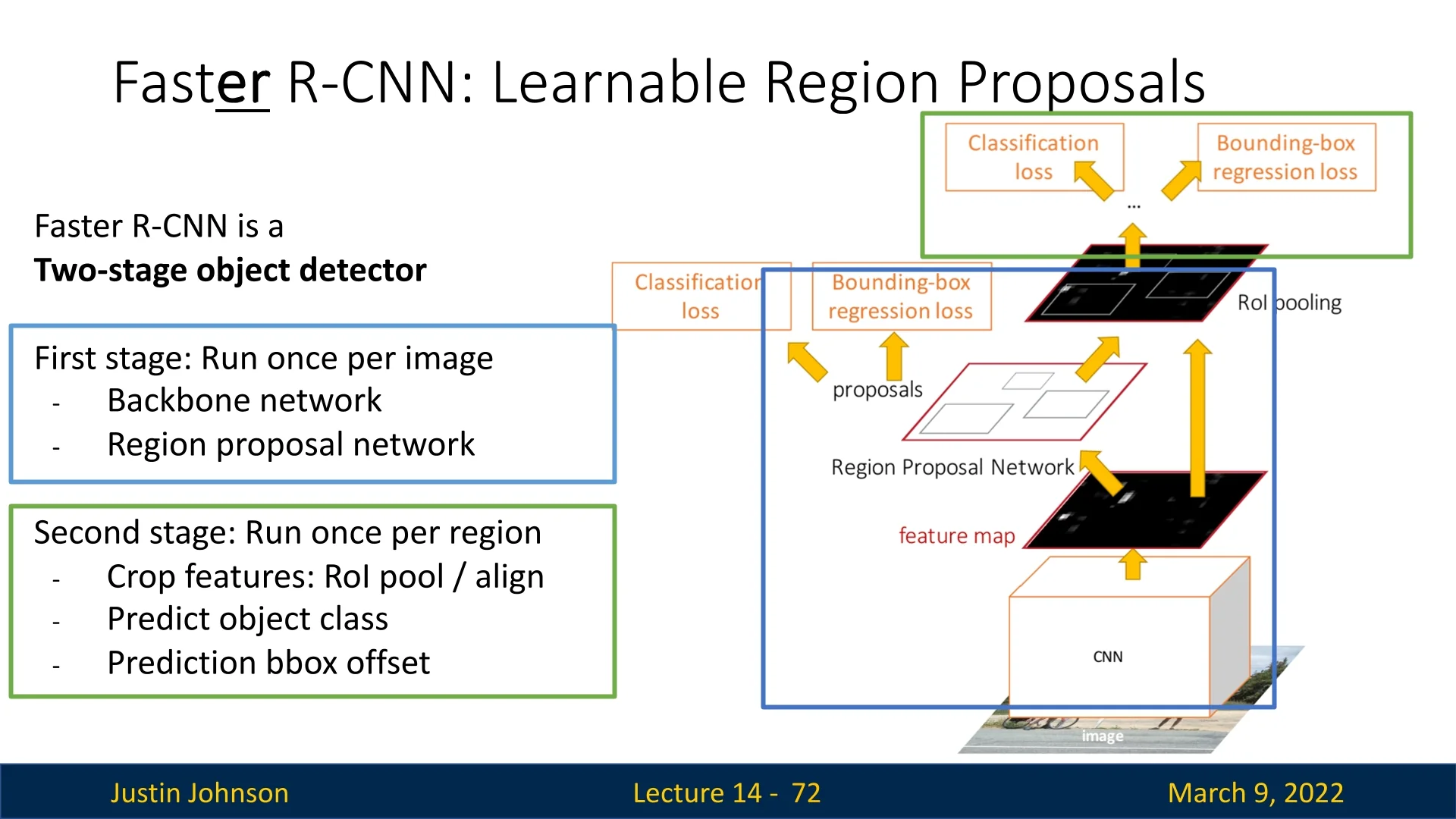

The natural next step in improving object detection efficiency was to replace the handcrafted, CPU-based proposal generation process with a learnable, CNN-based alternative. Faster R-CNN introduced the Region Proposal Network (RPN) [523], an architecture that predicts object proposals directly from the feature maps produced by the backbone CNN. This approach integrates proposal generation into the deep learning pipeline, eliminating the need for slow external algorithms.

The key idea behind RPNs is:

- Use convolutional feature maps to directly predict high-quality object proposals.

- Train the proposal generator jointly with the rest of the detection pipeline.

- Make the entire object detection process fully differentiable and GPU-accelerated.

By replacing Selective Search with an RPN, Faster R-CNN eliminates the last major bottleneck in Fast R-CNN and makes object detection significantly faster while maintaining high accuracy. In the next section, we will explore the details of Region Proposal Networks and their role in Faster R-CNN.

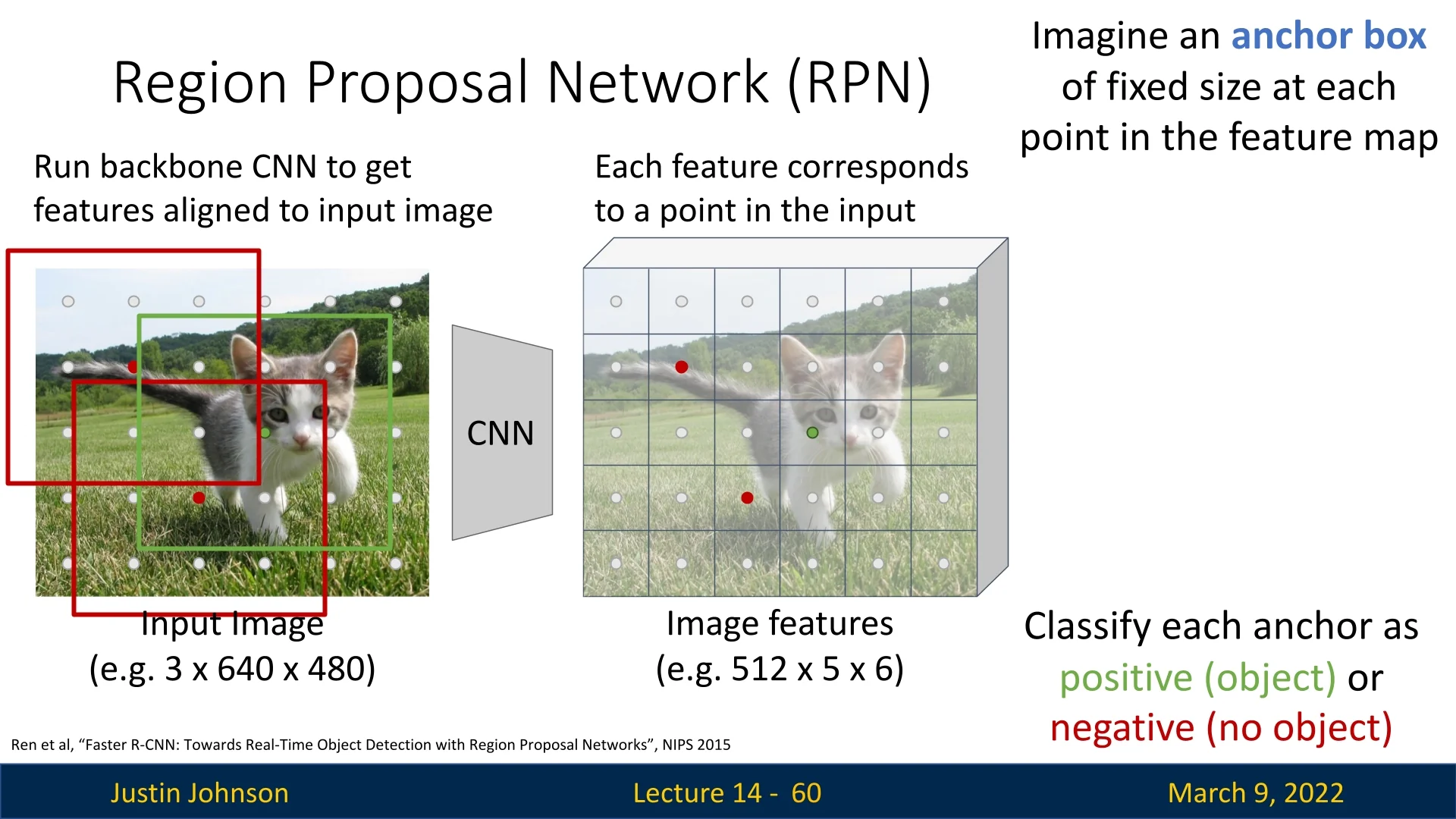

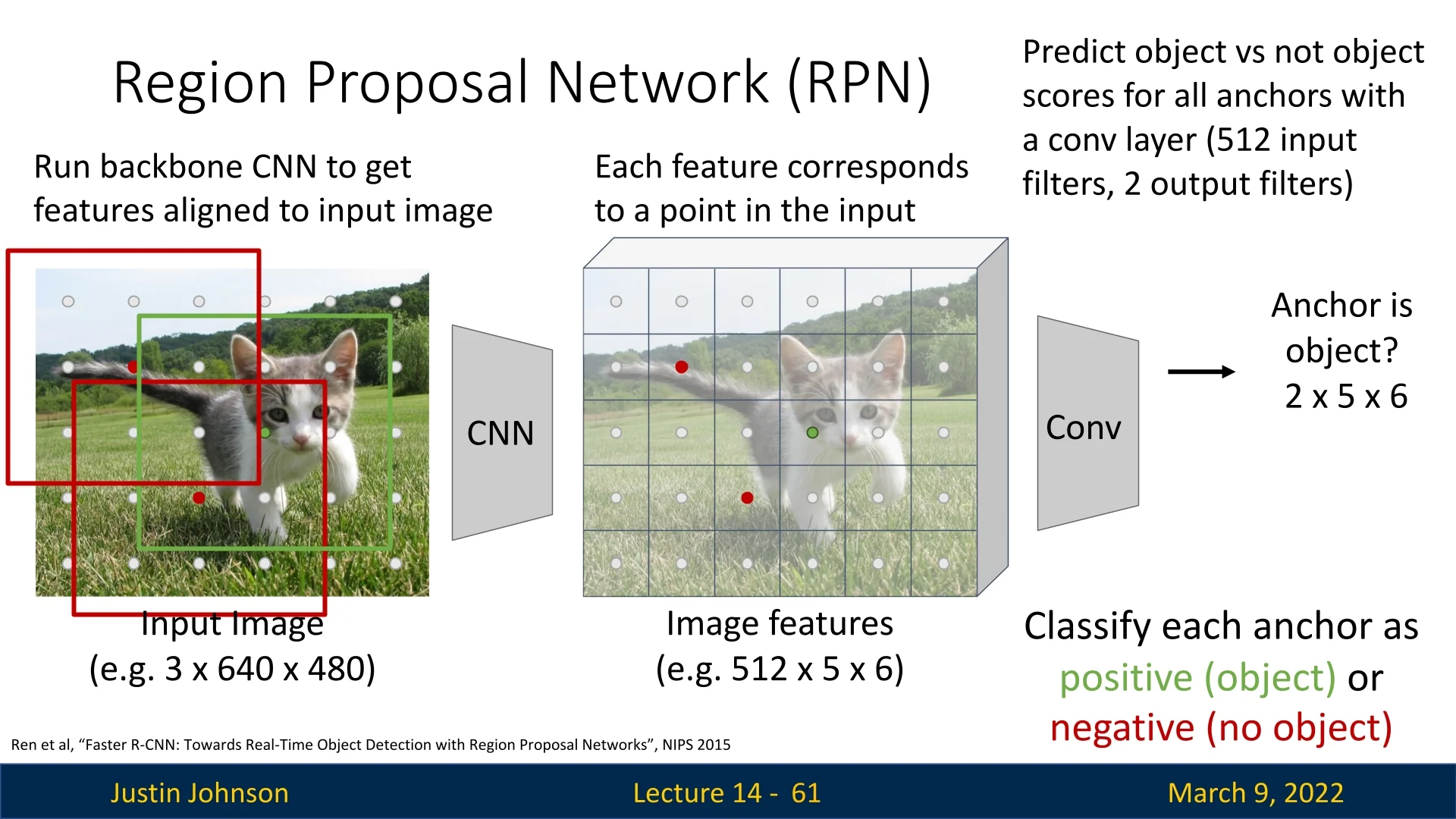

14.3.3 Region Proposal Networks (RPNs)

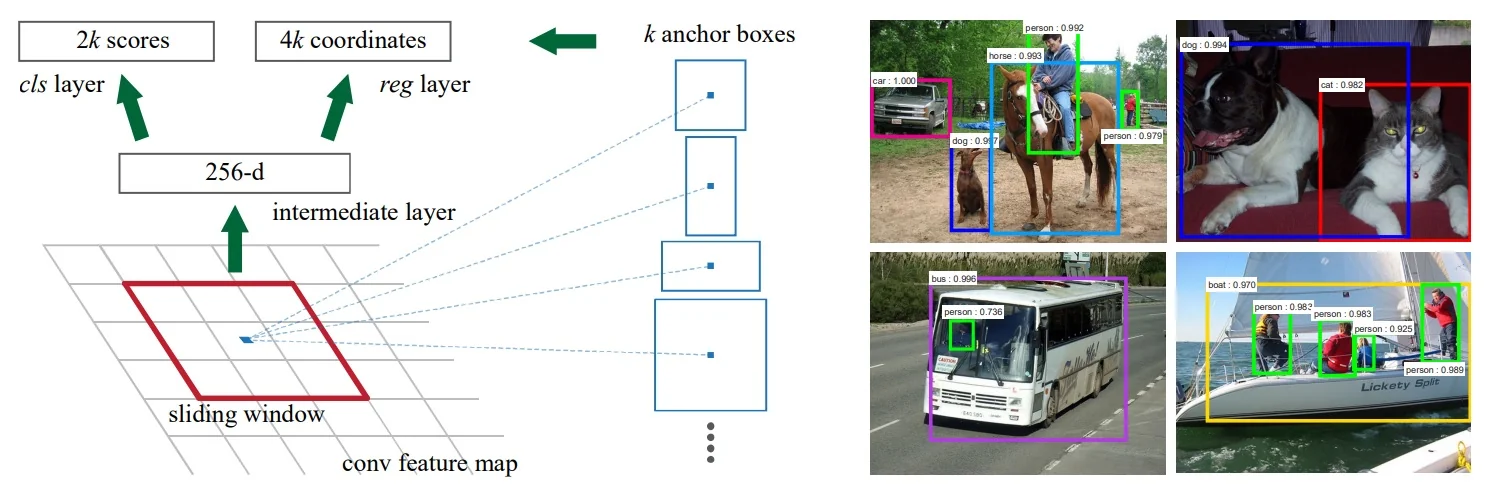

How RPNs Work Instead of using a separate region proposal algorithm, RPNs generate proposals directly from the shared feature map produced by a deep CNN backbone. The process follows these steps:

- 1.

- Feature Extraction: The backbone CNN extracts a feature map from the input image while preserving spatial alignment.

- 2.

- Anchor Generation: At each spatial location on the feature map, predefined anchor boxes (of multiple sizes and aspect ratios) serve as candidate proposals.

- 3.

- Objectness Classification: A small convolutional layer predicts whether each anchor contains an object.

- 4.

- Bounding Box Regression: For positive anchors, another convolutional layer predicts the transformation required to refine the anchor into a better-fitting bounding box.

Since the RPN operates directly on the shared feature map, it adds minimal computational cost—it is simply a small set of convolutional layers applied to the extracted backbone features. This allows the model to generate high-quality proposals without needing separate, slow region proposal methods.

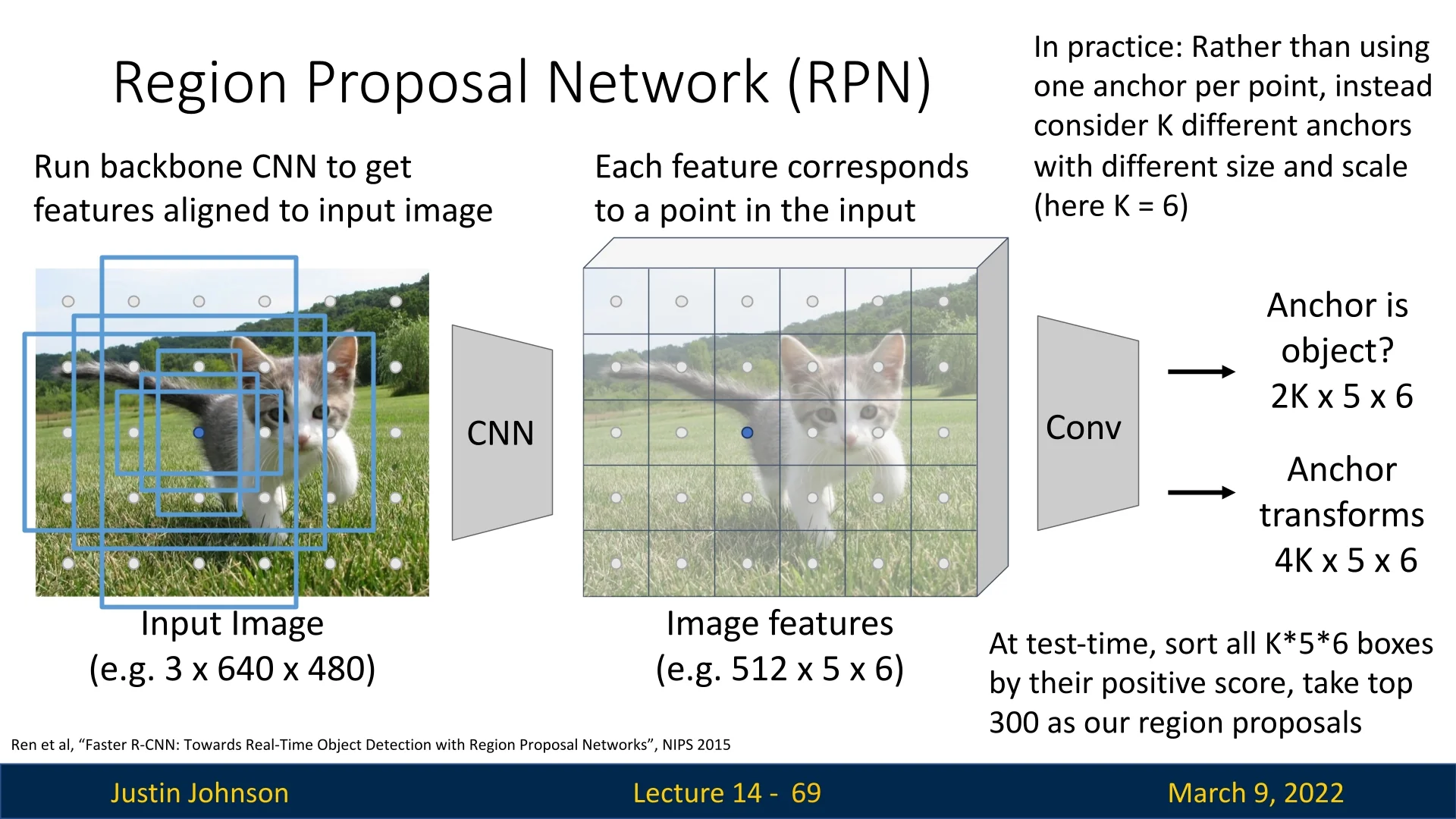

Anchor Boxes: Handling Scale and Aspect Ratio Variations In object detection, objects appear in diverse shapes and sizes. A single fixed-size proposal per spatial location would fail to capture this variability. To address this, RPNs generate proposals using a set of predefined anchor boxes at each spatial location on the feature map. Each anchor serves as a reference box that can be classified and refined to better fit actual objects.

At each spatial location, RPNs generate \(K\) anchors with:

- Different scales – Capturing small, medium, and large objects.

- Different aspect ratios – Adapting to tall, square, and wide objects.

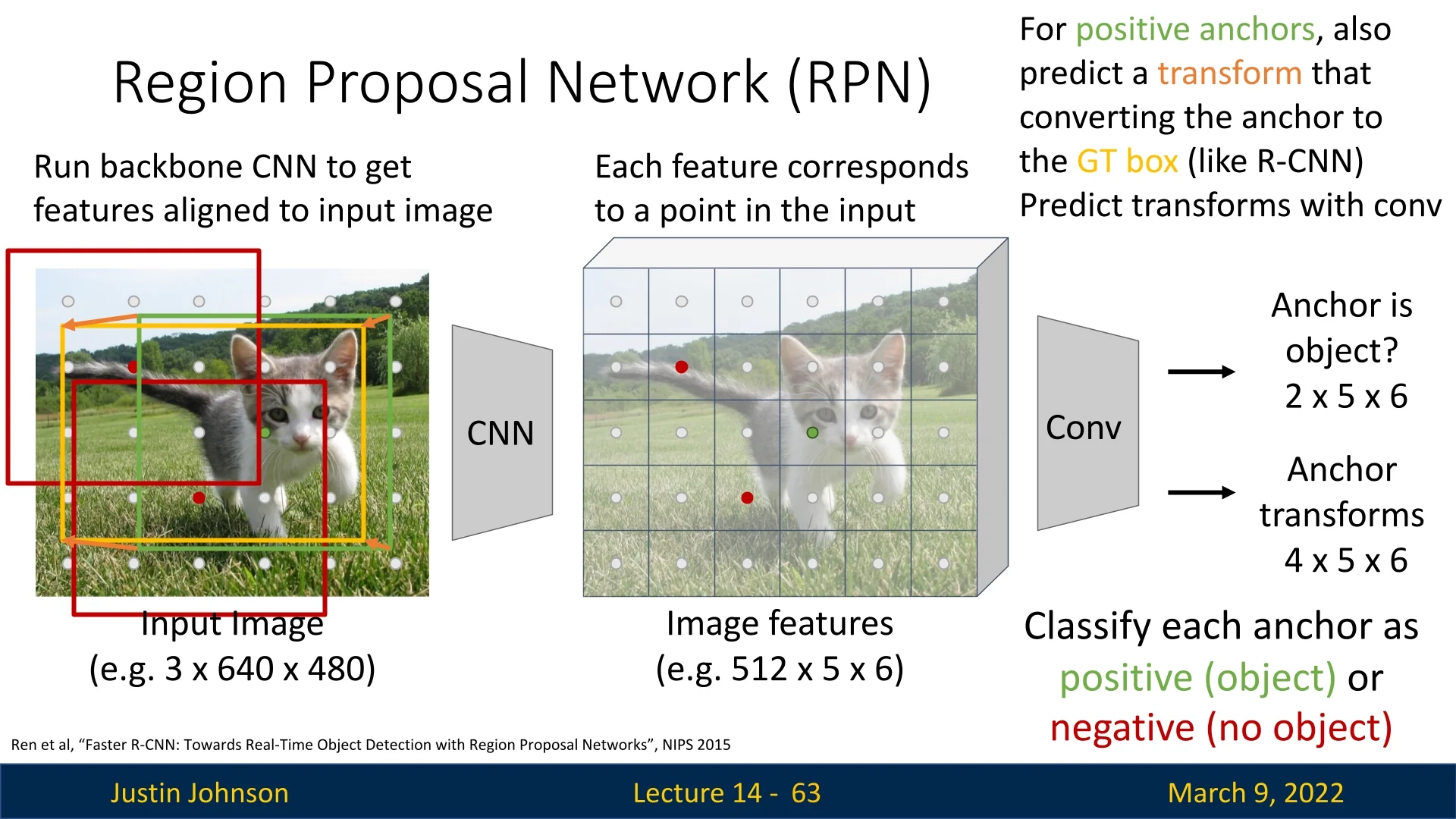

The original Faster R-CNN paper used 9 anchors per location (3 scales \(\times \) 3 aspect ratios). For each anchor, the RPN predicts:

- Objectness Score – A binary classification indicating whether the anchor contains a foreground object or belongs to background. Conceptually, this is just logistic regression: for each anchor we want a probability \(p(\mbox{object} \mid \mbox{anchor})\). In practice, most implementations parameterize this as two logits per anchor (foreground and background) and apply a softmax followed by a cross-entropy loss. For the binary case, this two-logit softmax formulation is mathematically equivalent to a single-logit sigmoid (standard logistic regression); it is simply more convenient to implement and extend to multi-class settings.

- Bounding Box Transform – A transformation \((t_x, t_y, t_w, t_h)\) refining the anchor box.

These predictions are made using a small CNN applied to the feature map. The classification branch outputs a \(2K\)-channel score map (for \(K\) anchors per location), i.e., for each spatial location it predicts two logits (foreground / background) for each of the \(K\) anchors. If the RPN feature map has spatial size \(5 \times 6\), this corresponds to a tensor of shape \(2K \times 5 \times 6\) per training image. The regression branch outputs a \(4K\)-channel transform map per spatial location, yielding an output tensor of shape \(4K \times 5 \times 6\) per training image.

Bounding Box Refinement: Aligning Anchors to Objects Even with multiple anchors per location, an anchor may not perfectly match an object’s true dimensions. To improve localization, the RPN predicts a refinement transformation, similar to what R-CNN and Fast R-CNN do for final detections. For details on bounding box transformations, refer to Section §14.

The refinement transformation is parameterized as follows:

\[ t_x = \frac {b_x - p_x}{p_w}, \quad t_y = \frac {b_y - p_y}{p_h}, \quad t_w = \ln \left ( \frac {b_w}{p_w} \right ), \quad t_h = \ln \left ( \frac {b_h}{p_h} \right ) \]

where \((p_x, p_y, p_w, p_h)\) are the anchor box parameters and \((b_x, b_y, b_w, b_h)\) are the refined bounding box parameters.

Unlike traditional proposal generation methods, RPNs train the proposal generation process jointly with the feature extraction backbone, allowing the network to learn proposals that are well-suited for the final detection task. This integration improves both accuracy and computational efficiency.

Training RPNs: Assigning Labels to Anchors To train a Region Proposal Network (RPN), we must assign labels to the anchor boxes, distinguishing between positive, negative, and neutral examples. This labeling process is crucial for optimizing both classification (objectness score) and bounding box regression.

- Positive anchors: Anchors that have an IoU \(\geq 0.7\) with at least one ground-truth box are considered positive.

- Negative anchors: Anchors with IoU \(< 0.3\) with all ground-truth boxes are labeled negative.

- Neutral anchors: Anchors with an IoU between 0.3 and 0.7 are ignored during training.

Since anchor boxes serve as a reference for object detection, positive anchors are used to compute both classification and regression losses.

Negative anchors, on the other hand, only contribute to the classification loss, ensuring the RPN learns to distinguish objects from background effectively.

Loss Function for RPN Training The RPN is trained using a multi-task loss function that jointly optimizes object classification and bounding box regression:

\[ L(\{p_i\}, \{t_i\}) = \frac {1}{N_{\mbox{cls}}} \sum _{i} L_{\mbox{cls}}(p_i, p^*_i) + \lambda \frac {1}{N_{\mbox{reg}}} \sum _{i} p^*_i L_{\mbox{reg}}(t_i, t^*_i) \]

where:

- \( p_i \) is the predicted probability of anchor \( i \) containing an object.

- \( p^*_i \) is the ground-truth label (1 for objects, 0 for background).

- \( t_i \) is the predicted bounding box transform for anchor \( i \).

- \( t^*_i \) is the ground-truth bounding box transform.

- \( L_{\mbox{cls}} \) is the binary cross-entropy loss for object classification.

- \( L_{\mbox{reg}} \) is the smooth \( L_1 \) loss applied only to positive anchors.

- \( N_{\mbox{cls}} \) and \( N_{\mbox{reg}} \) are normalization terms.

- \( \lambda \) is a balancing factor, typically set to 10.

This loss function ensures that classification and bounding box regression are optimized simultaneously.

Assigning Ground-Truth Bounding Boxes to Anchors Each positive anchor is assigned to the ground-truth box that has the maximum IoU with it. This ensures that the best-matching ground-truth object supervises the training of the anchor’s bounding box regression.

- If an anchor has \(\mbox{IoU} \geq 0.7\) with multiple ground-truth boxes, it is assigned to the object with which it has the highest IoU.

- Each ground-truth box must be matched to at least one anchor. If no anchor has \(\mbox{IoU} \geq 0.7\) with a given ground-truth box, the anchor with the highest IoU is forcibly assigned to it.

This matching process ensures that all ground-truth objects are covered by at least one anchor, enabling the RPN to propose accurate regions for all objects in an image.

Smooth \( L_1 \) Loss for Bounding Box Regression To refine anchor boxes into accurate region proposals, Faster R-CNN employs the smooth \( L_1 \) loss, which is defined as:

\[ L_{\mbox{reg}}(t_i, t^*_i) = \begin {cases} 0.5 (t_i - t^*_i)^2, & \mbox{if } |t_i - t^*_i| < 1 \\ |t_i - t^*_i| - 0.5, & \mbox{otherwise} \end {cases} \]

This loss behaves like an \( L_2 \) loss (squared error) when the error is small, ensuring smooth gradients for small offsets. However, for larger errors, it switches to an \( L_1 \) loss (absolute error), preventing large outliers from dominating the training process.

Why Smooth \( L_1 \) Instead of \( L_2 \) Loss?

- Robustness to Outliers: Unlike the \( L_2 \) loss, which heavily penalizes large errors, the smooth \( L_1 \) loss reduces the influence of extreme outliers.

- Stable Training: The transition from quadratic to linear loss ensures that large localization errors do not cause excessively high gradients, making optimization more stable.

- Better Localization: Since bounding box predictions can have large variations, the smooth \( L_1 \) loss allows more effective training, focusing on improving the fine alignment of predicted boxes.

By integrating the smooth \( L_1 \) loss into the RPN’s training objective, Faster R-CNN achieves more accurate and stable region proposals, leading to improved object detection performance.

Why Use Negative Anchors? Negative anchors (IoU \(<\) 0.3) play a crucial role in training the RPN. Without them, the model would lack supervision on how to classify background regions, leading to an excess of false positives. Negative anchors:

- Ensure the RPN learns to reject background regions by reinforcing the binary classification task.

- Provide a balance between object detection and background rejection, making the system more robust (ensuring that the RPN does not overfit to detecting only foreground objects).

Enrichment 14.3.3.1: Training Region Proposal Networks (RPNs)

The Region Proposal Network (RPN) [522] is a learnable module for generating class-agnostic object proposals from convolutional feature maps. Below is a complete walkthrough of the training process.

1. Input Feature Map Given an input image \( I \in \mathbb {R}^{H \times W \times 3} \), a CNN backbone (e.g., VGG-16, ResNet-50) produces a feature map of spatial dimensions: \[ F \in \mathbb {R}^{H' \times W' \times C'}, \quad \mbox{where } H' = H/s,\, W' = W/s. \] The stride \( s \) reflects total downsampling (often \( s = 16 \)).

A shared \(3 \times 3\) conv is applied across all spatial locations to extract intermediate features:

# Shared intermediate 3x3 conv

rpn_conv = nn.Conv2d(C_prime, 512, kernel_size=3, padding=1)

inter_features = F.relu(rpn_conv(featmap)) # (B, 512, H’, W’)Each spatial location corresponds to a position in the original image and will be associated with \(K\) anchor boxes.

3. RPN Heads: Anchor-wise Classification and Regression Two parallel \(1\times 1\) conv layers produce:

- Objectness scores: \(2K\) channels (foreground vs. background for each anchor),

- BBox deltas: \(4K\) channels (\(\Delta x, \Delta y, \Delta w, \Delta h\) for each anchor).

rpn_cls_logits = nn.Conv2d(512, 2 * K, kernel_size=1)(inter_features)

rpn_bbox_deltas = nn.Conv2d(512, 4 * K, kernel_size=1)(inter_features)These outputs are reshaped to \((B, H' \times W' \times K, 2)\) and \((B, H' \times W' \times K, 4)\) respectively during training for loss computation, to associate each anchor with its corresponding predictions:

rpn_cls_logits = rpn_cls_logits.permute(0, 2, 3, 1).reshape(B, -1, 2)

rpn_bbox_deltas = rpn_bbox_deltas.permute(0, 2, 3, 1).reshape(B, -1, 4)4. Anchor Labeling and Ground Truth Assignment To train the network, we must determine which anchors are positive (object), negative (background), or ignored. For this, we compute the IoU (Intersection-over-Union) between each anchor and each ground-truth box:

- Positive: An anchor is labeled positive if it has an IoU \(\ge 0.7\) with any GT box, or if it is the highest-IoU anchor for a given GT.

- Negative: Labeled background if it has IoU \(\le 0.3\) with all GT boxes.

- Ignored: Anchors with intermediate IoU scores are not used in the loss.

labels, matched_gt_boxes = assign_labels(all_anchors, gt_boxes)

# labels: 1 = positive, 0 = negative, -1 = ignore

pos_inds = torch.where(labels == 1)[0] # Indices of positive anchors

fg_bg_inds = torch.where(labels != -1)[0] # Anchors involved in loss5. Bounding-Box Regression Targets For each positive anchor, we compute the offset required to transform the anchor into its assigned ground-truth box. These offsets form the regression targets.

Each target is parameterized as: \[ \Delta x = \frac {x_{\mbox{gt}} - x_{\mbox{anchor}}}{w_{\mbox{anchor}}}, \quad \Delta y = \frac {y_{\mbox{gt}} - y_{\mbox{anchor}}}{h_{\mbox{anchor}}}, \quad \Delta w = \log \frac {w_{\mbox{gt}}}{w_{\mbox{anchor}}}, \quad \Delta h = \log \frac {h_{\mbox{gt}}}{h_{\mbox{anchor}}}. \]

These values measure:

- The relative translation (\(\Delta x, \Delta y\)) of the ground-truth box center w.r.t. the anchor box.

- The log-scale change (\(\Delta w, \Delta h\)) needed to stretch the anchor’s width/height to match the ground truth.

bbox_targets = compute_regression_targets(anchors[pos_inds], matched_gt_boxes[pos_inds])

# Shape: (N_pos, 4)These targets serve as supervision: the network learns to predict these deltas for each positive anchor.

6. Loss Computation The RPN is trained using a multi-task loss: \[ \mathcal {L}_{\mbox{RPN}} = \frac {1}{N_{\mbox{cls}}} \sum _i \mathcal {L}_{\mbox{cls}}(p_i, p_i^*) + \lambda \cdot \frac {1}{N_{\mbox{reg}}} \sum _i \mathbb {1}_{\{p_i^* = 1\}} \cdot \mathcal {L}_{\mbox{reg}}(t_i, t_i^*), \] where:

- \(p_i\): predicted objectness logits (before softmax),

- \(p_i^*\): binary GT label (1 for object, 0 for background),

- \(t_i\): predicted regression deltas (rpn_bbox_deltas),

- \(t_i^*\): GT regression target (bbox_targets).

cls_loss = F.cross_entropy(rpn_cls_logits[fg_bg_inds], labels[fg_bg_inds])

reg_loss = smooth_l1_loss(rpn_bbox_deltas[pos_inds], bbox_targets)

total_loss = cls_loss + lambda_ * reg_lossNote: During training, we do not decode or apply the predicted deltas to anchors. Instead, we supervise the raw predicted deltas directly, using regression targets computed from fixed anchor–GT box pairs. This ensures stable optimization, as the anchors remain fixed while the network learns to output precise \((\Delta x, \Delta y, \Delta w, \Delta h)\) shifts. Only at inference time do we apply these predicted offsets to anchors to produce proposal boxes.

Inference: Generating Region Proposals At inference time, the RPN processes all anchor boxes across the image and filters out low-confidence proposals to retain the most relevant ones. The process consists of the following steps:

- 1.

- Compute objectness scores: The classification branch predicts an object score for each anchor box.

- 2.

- Sort proposals by objectness score: The top-scoring anchors are retained for further processing.

- 3.

- Apply Non-Maximum Suppression (NMS): Overlapping proposals with a high IoU are removed, keeping only the most confident detections.

- 4.

- Select the top \(N\) proposals (e.g., 300 proposals) as final region proposals for Fast R-CNN.

By filtering out redundant and low-confidence proposals, this step improves both efficiency and accuracy, ensuring that only the most relevant regions are processed by the detector.

RPNs Improve Region Proposal Generation Compared to previous region proposal methods like Selective Search, RPNs introduce several key advantages:

- Speed: RPNs operate directly on the backbone’s shared feature map as a small conv head. Proposal generation becomes a single GPU pass instead of a slow, separate CPU algorithm.

- Learned “Objectness”: Because the RPN is trained jointly with the detector, it learns which regions in feature space are likely to contain any object, rather than relying on hand-crafted low-level grouping cues. This produces proposals that are more relevant to the downstream detection task (fewer obvious background regions, more boxes covering real objects).

- More Precise Localization: Each positive anchor is not only classified as “object vs. background,” but also refined by a learned bounding box regressor that predicts offsets \(((t_x, t_y, t_w, t_h))\). This allows the network to adjust coarse anchors to tightly hug the true object boundaries, resulting in proposals that overlap ground-truth boxes much more accurately than the fixed, heuristic boxes from Selective Search.

Thus, Faster R-CNN achieves real-time object detection by integrating RPNs and Fast R-CNN into a unified pipeline.

14.3.4 Faster R-CNN Loss in Practice: Joint Training with Four Losses

Joint Training in Faster R-CNN Unlike previous object detection pipelines where region proposal generation and object classification were trained separately, Faster R-CNN jointly trains both the RPN and the object detector. This results in a fully end-to-end learnable system with a four-part loss function:

\[ L = L_{\mbox{cls}}^{\mbox{RPN}} + L_{\mbox{reg}}^{\mbox{RPN}} + L_{\mbox{cls}}^{\mbox{Fast R-CNN}} + L_{\mbox{reg}}^{\mbox{Fast R-CNN}} \]

- \( L_{\mbox{cls}}^{\mbox{RPN}} \) – Classifies anchor boxes as object vs. background.

- \( L_{\mbox{reg}}^{\mbox{RPN}} \) – Refines anchor boxes to generate high-quality proposals.

- \( L_{\mbox{cls}}^{\mbox{Fast R-CNN}} \) – Classifies refined proposals into object categories.

- \( L_{\mbox{reg}}^{\mbox{Fast R-CNN}} \) – Further refines bounding box localization.

By training the RPN together with the detection network, the region proposal generation and object detection become more aligned, improving both efficiency and accuracy.

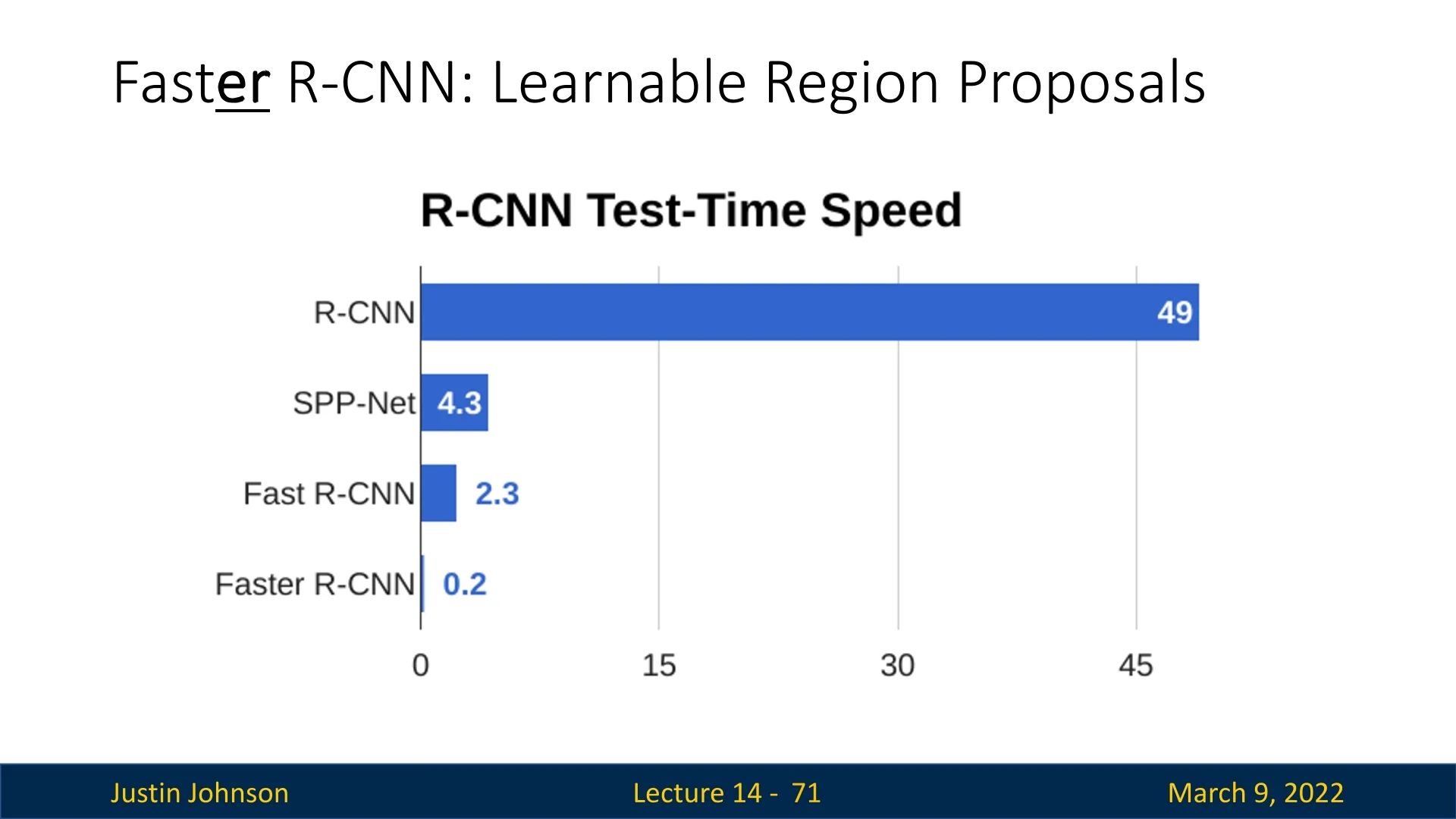

How RPN Improves Inference Speed Before Faster R-CNN, Fast R-CNN significantly reduced inference time compared to R-CNN by sharing computations. However, it still relied on external region proposal methods such as Selective Search, which were computationally expensive. Faster R-CNN eliminates this bottleneck by using RPN to generate region proposals directly from the feature map.

Key Takeaways:

- Eliminating external region proposals – Instead of using a separate CPU-based region proposal method (e.g., Selective Search), Faster R-CNN predicts region proposals using CNNs.

- Fully convolutional region proposals – The RPN operates as a small, efficient convolutional network on top of the shared feature map.

- Dramatic speedup – With RPN, the overall test-time speed improves from 2.3s in Fast R-CNN to just 0.2s in Faster R-CNN, making real-time object detection more feasible.

By integrating joint training, region proposal learning, and feature sharing, Faster R-CNN achieves significant improvements over previous detectors, making it one of the most influential object detection models.

14.3.5 Feature Pyramid Networks (FPNs): Multi-Scale Feature Learning

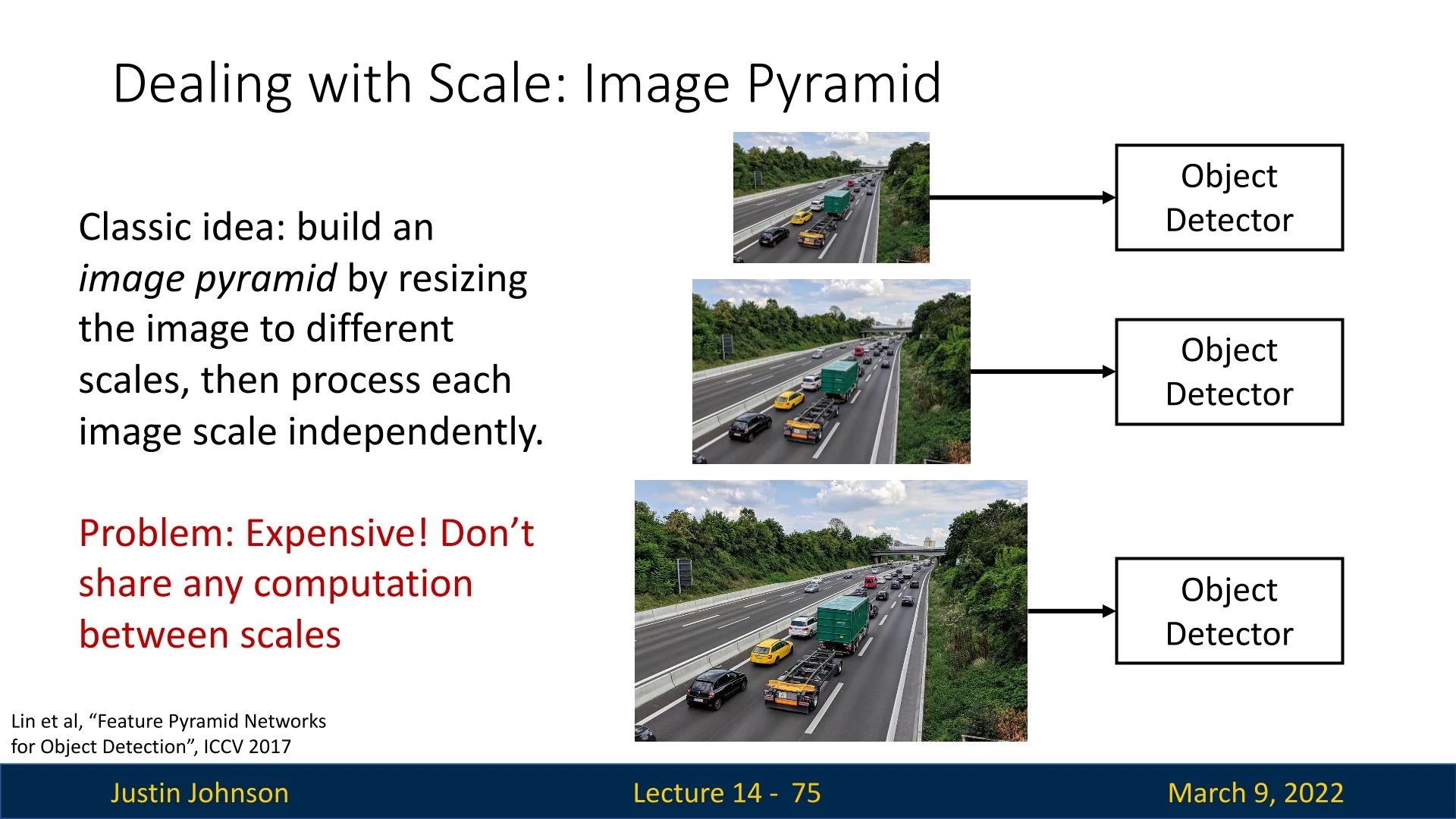

Detecting objects of varying scales is a fundamental challenge in object detection. Traditional methods attempted to improve scale invariance by constructing an image pyramid, where the image is resized to multiple scales and processed separately by the detector. This approach is computationally expensive since the network must process the same image multiple times.

Feature Pyramid Networks: A More Efficient Approach

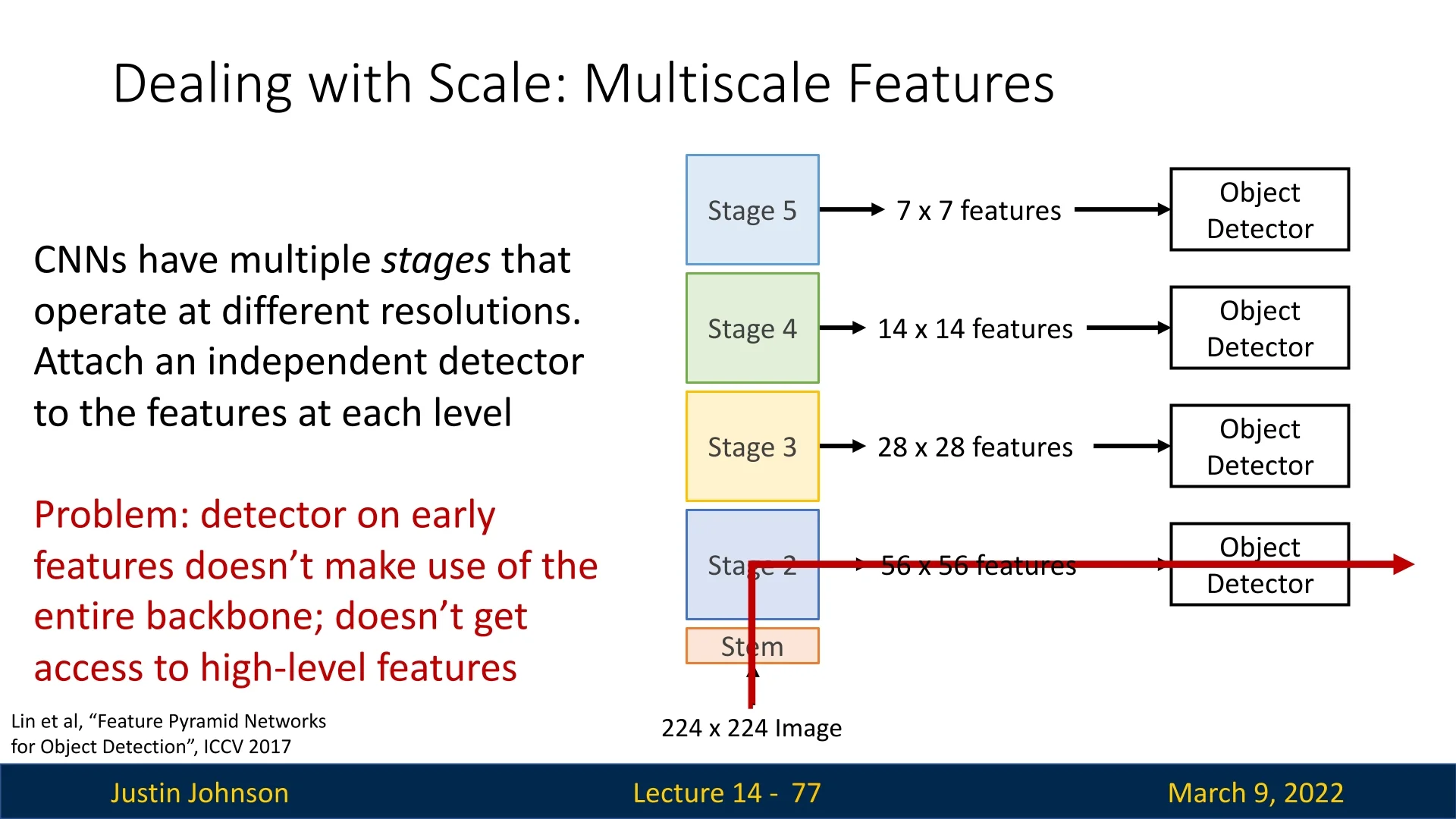

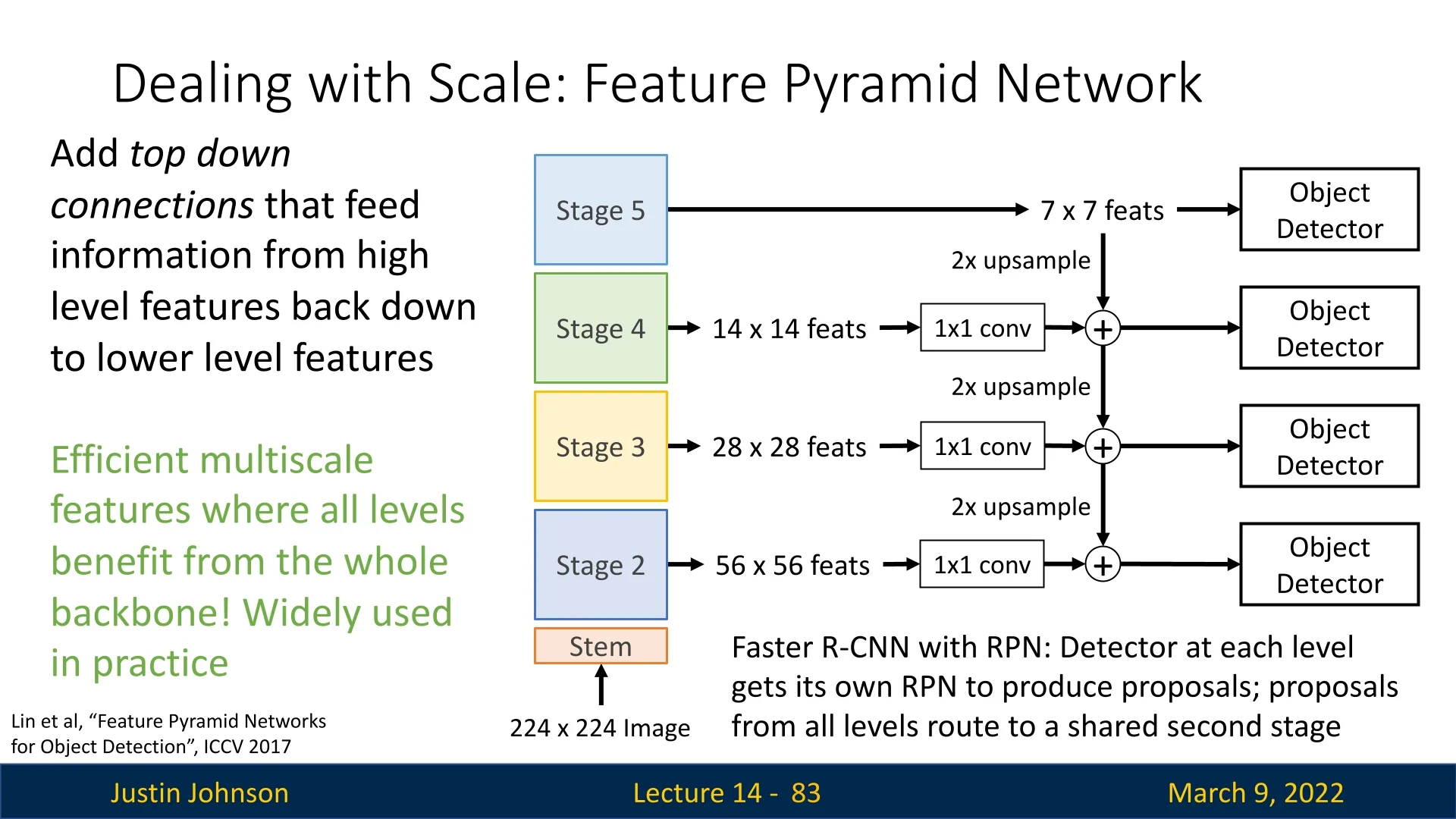

Rather than resizing the image, Lin et al. (2017) [359] proposed leveraging the inherent hierarchical structure of convolutional neural networks (CNNs). Since CNNs naturally extract features at multiple resolutions due to their deep architecture, FPNs attach independent detectors to features from multiple levels of the backbone. This enables the model to handle objects at different scales without requiring multiple forward passes.

Enhancing Low-Level Features with High-Level Semantics

A major drawback of using early-stage CNN features for object detection is that they lack semantic richness. Lower layers in CNNs retain high spatial resolution but primarily capture edges and textures, whereas deeper layers encode more complex features but at a lower resolution. This results in a trade-off: high-resolution features lack meaningful context, while low-resolution features are more informative but spatially coarse.

To address this, FPNs introduce top-down connections that propagate high-level information back to lower-resolution feature maps.

Specifically, the process consists of the following steps:

- 1.

- Each feature map from the backbone undergoes a \(1\times 1\) convolution to change its channel dimensionality. This ensures that features from different levels are compatible when combined.

- 2.

- The highest-level feature map (smallest spatial size, richest semantic information) is directly used as the starting point for the top-down pathway.

- 3.

- The lower-resolution feature maps are then progressively upsampled using bilinear interpolation or transposed convolution (also known as deconvolution) to match the spatial resolution of the next finer feature map.

- 4.

- The upsampled feature map is then element-wise added to the corresponding feature map from the backbone (which retains high spatial resolution but lacks deep semantic information).

- 5.

- Finally, the fused feature maps are further processed by a \(3\times 3\) convolution to smooth out artifacts introduced by upsampling and fusion before being used for object detection.

How Upsampling Works in FPNs Upsampling is a crucial operation in FPNs since it allows coarse but high-level features to be brought into alignment with finer-resolution feature maps. This is typically done in one of two ways:

- Bilinear Interpolation: A non-learnable method we’ve covered that interpolates pixel values based on surrounding features, and can be used to produce smooth upscaled feature maps.

- Transposed Convolution (Deconvolution): A learnable operation that applies upsampling with trainable filters, allowing the network to learn an optimal way to refine features during backpropagation. We’ll cover it in more detail later, when we’ll discuss segmentation.

By applying these top-down connections, FPNs create a hierarchical feature representation where all levels of the feature pyramid benefit from deep semantic information. This significantly improves object detection performance, especially for small objects, by ensuring that all feature levels contribute meaningful information to the final detections.

Combining Results from Multiple Feature Levels

Once object detections are generated from multiple feature levels, they must be merged to produce a final prediction. The standard approach is to apply Non-Maximum Suppression (NMS) across all detections:

- Sort all detected bounding boxes by confidence score.

- Iteratively suppress overlapping boxes with lower confidence, ensuring that redundant detections do not appear in the final output.

Advantages of FPNs Feature Pyramid Networks offer several key advantages over traditional multi-scale detection approaches:

- Efficient multi-scale feature extraction – The network processes the image only once, rather than at multiple scales.

- Enhanced small-object detection – Lower-resolution feature maps retain fine details while incorporating high-level semantics.

- Lightweight and scalable – The additional computational cost of FPNs is minimal compared to constructing an image pyramid.

By efficiently integrating information from different levels of a CNN, FPNs have become a standard component in modern object detection architectures, including Faster R-CNN.

The Two-Stage Object Detection Pipeline Faster R-CNN is a two-stage object detector, meaning the detection process is divided into two sequential steps:

- 1.

- Stage 1: Region Proposal Generation

- The backbone CNN processes the entire image once to generate a feature map.

- The Region Proposal Network (RPN) applies convolutional layers to the feature map and outputs a set of region proposals, each with an objectness score and bounding box transform.

- The top \(N\) proposals (e.g., 300) are selected using Non-Maximum Suppression (NMS) to remove redundant boxes.

- 2.

- Stage 2: Object Detection and Classification

- The extracted feature map is cropped using RoIPooling, producing fixed-size feature vectors for each proposal.

- Each proposal is classified into an object category or background.

- A final bounding box refinement transformation improves localization accuracy.

This two-stage approach provides high accuracy but comes at the cost of increased computational complexity. Faster R-CNN significantly improves inference speed over its predecessors, yet the sequential pipeline—first generate proposals, then run a per-proposal classifier and regressor—still limits real-time performance.

A natural follow-up question is: do we really need a separate second stage at all? Notice that the RPN in Stage 1 is already a small, fully convolutional network that scans the feature map and predicts both an objectness score and bounding box offsets for many locations. In other words, it is almost a detector by itself—just with a very simple label space (“object vs. background”).

This observation motivated a new family of single-stage object detectors. Instead of first proposing regions and then classifying them, these models predict object categories and bounding boxes directly from the feature maps in one pass, removing the explicit proposal stage.

In the following sections, we will study this paradigm through RetinaNet [360], which introduces the Focal Loss to tackle severe class imbalance in dense prediction, and FCOS [617], a fully convolutional anchor-free detector that further simplifies the design. Later, after introducing Transformers, we will return to this idea with DEtection TRansformer (DETR) [64], a modern single-stage detector that formulates object detection as a set prediction problem.

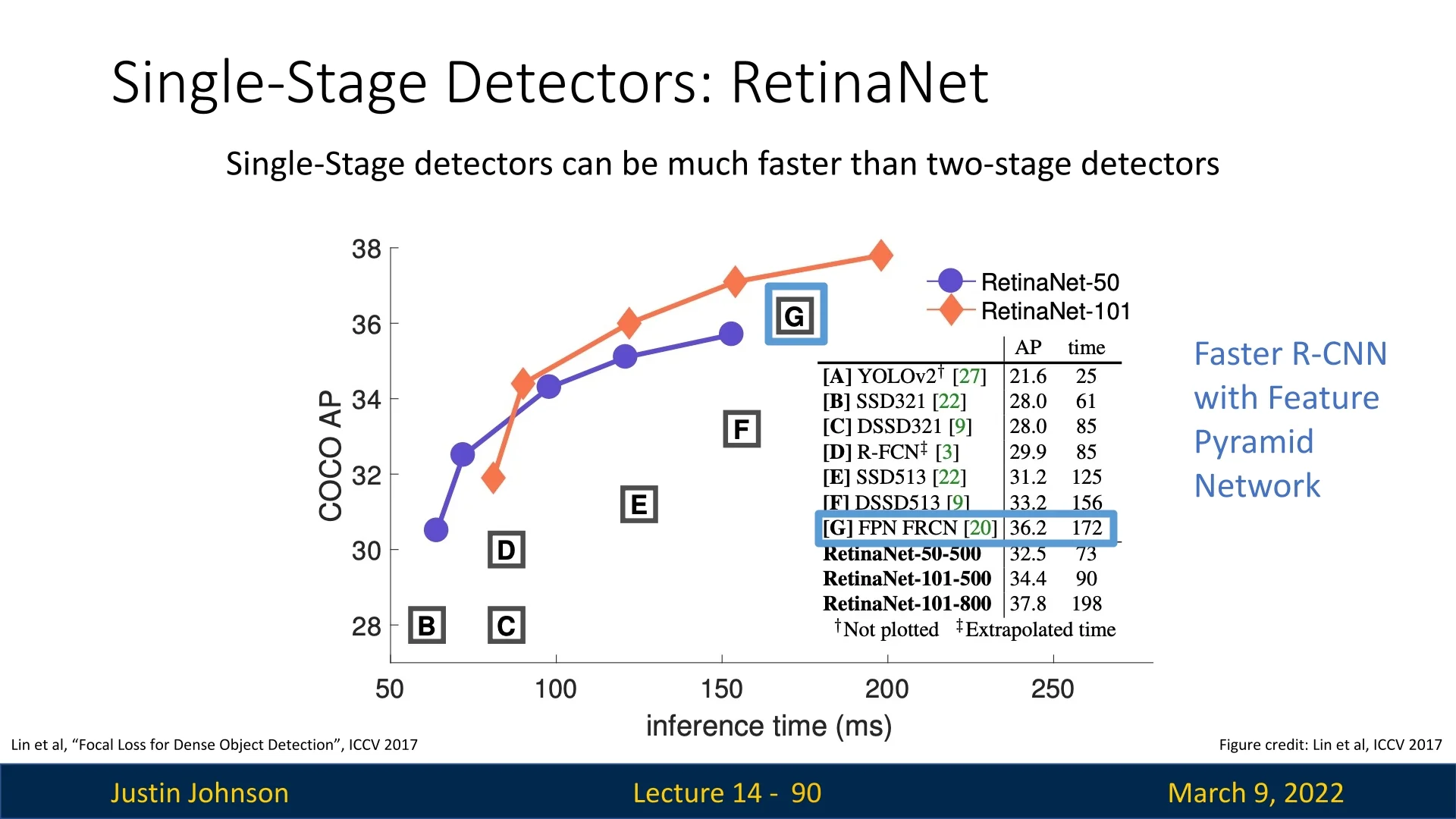

14.4 RetinaNet: A Breakthrough in Single-Stage Object Detection

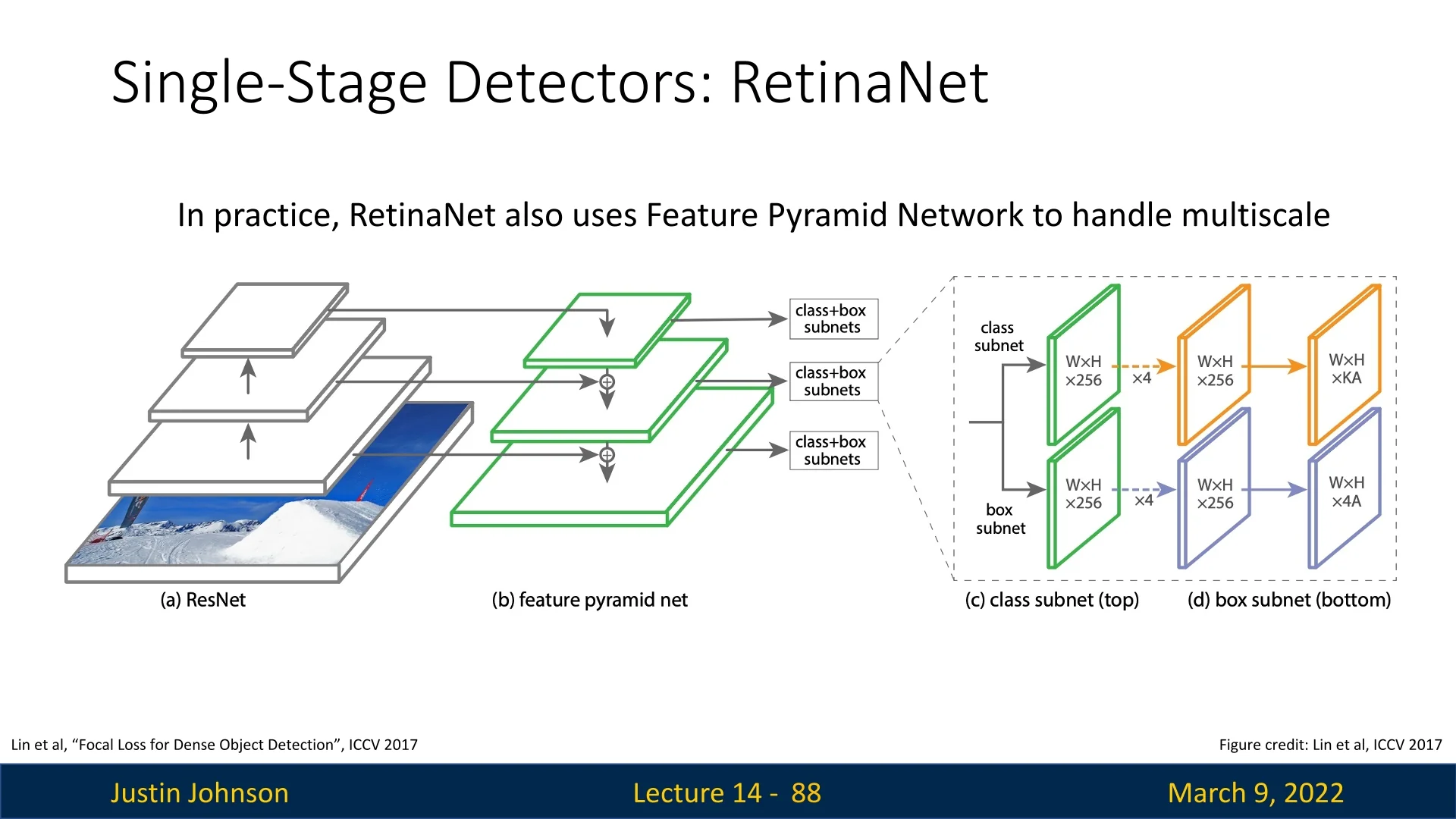

RetinaNet [360] was a major breakthrough in object detection, becoming the first single-stage detector to surpass the performance of top two-stage methods such as Faster R-CNN. It is based on a ResNet-101-FPN or ResNeXt-101-FPN backbone, where the Feature Pyramid Network (FPN) serves as the neck. By leveraging FPN, RetinaNet effectively handles multi-scale object detection while maintaining high efficiency.

14.4.1 Why Single-Stage Detectors Can Be Faster

Single-stage object detectors predict object categories and bounding boxes directly from feature maps, eliminating the need for a region proposal step. Unlike Faster R-CNN, which processes only a few thousand region proposals per image, single-stage detectors like RetinaNet operate on a dense grid of anchor boxes—potentially processing over 100,000 candidate regions in a single forward pass.

- Efficiency: Instead of applying a second-stage classifier per proposal, RetinaNet classifies objects in a single step, reducing inference time.

- Parallelization: Since all predictions are made in parallel, one-stage detectors can fully utilize modern hardware like GPUs.

However, despite these advantages, single-stage detectors historically struggled with class imbalance, which RetinaNet successfully addresses.

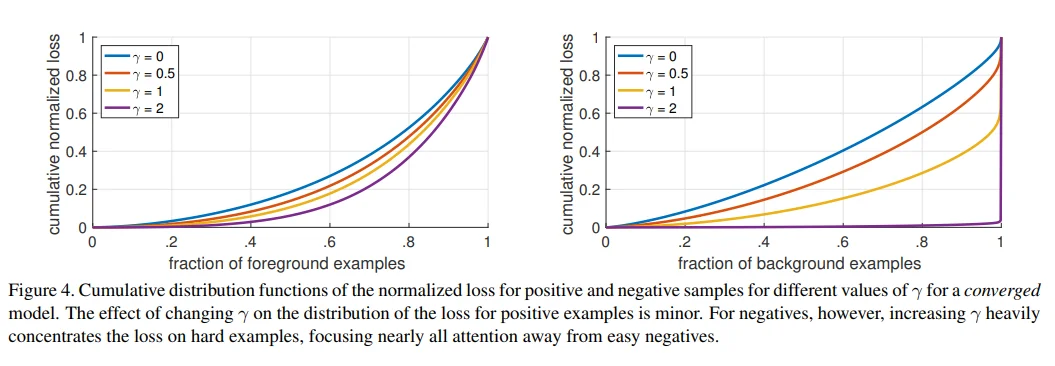

14.4.2 The Class Imbalance Problem in Dense Detection

One of the main challenges in single-stage detection is extreme foreground–background class imbalance. Because these detectors make predictions densely over the entire feature map, they evaluate tens of thousands (sometimes over 100,000) of anchors per image, while only a tiny fraction of them actually overlap a ground-truth object.

Concretely, this means that the vast majority of anchors are easy background examples. This imbalance causes two related problems:

- 1.

- Inefficient training: Most negative anchors are trivial to classify as background, so their individual loss and gradients are very small. Yet they still consume most of the computation in each forward/backward pass. The network spends a lot of effort repeatedly confirming “this is background” instead of learning from the relatively few informative foreground examples and hard negatives.

- 2.

- Domination of the loss by easy negatives: Although each easy background anchor contributes only a tiny loss, their sheer quantity means their summed contribution can overwhelm the loss from the few positive anchors. In this regime, a degenerate solution that simply predicts “background” almost everywhere can achieve low average loss and high raw accuracy, while completely failing to detect objects (very low recall). The optimizer is therefore biased toward modeling the majority background class well, rather than learning strong features for the rare foreground class.

This issue is much less severe in two-stage detectors like Faster R-CNN, where the RPN filters out most background regions before the second-stage classifier, leaving a more balanced subset of positive and negative proposals for training.

RetinaNet’s key contribution is to tackle this imbalance at the loss level, introducing the Focal Loss to down-weight easy negatives so that training focuses on the scarce, informative examples.

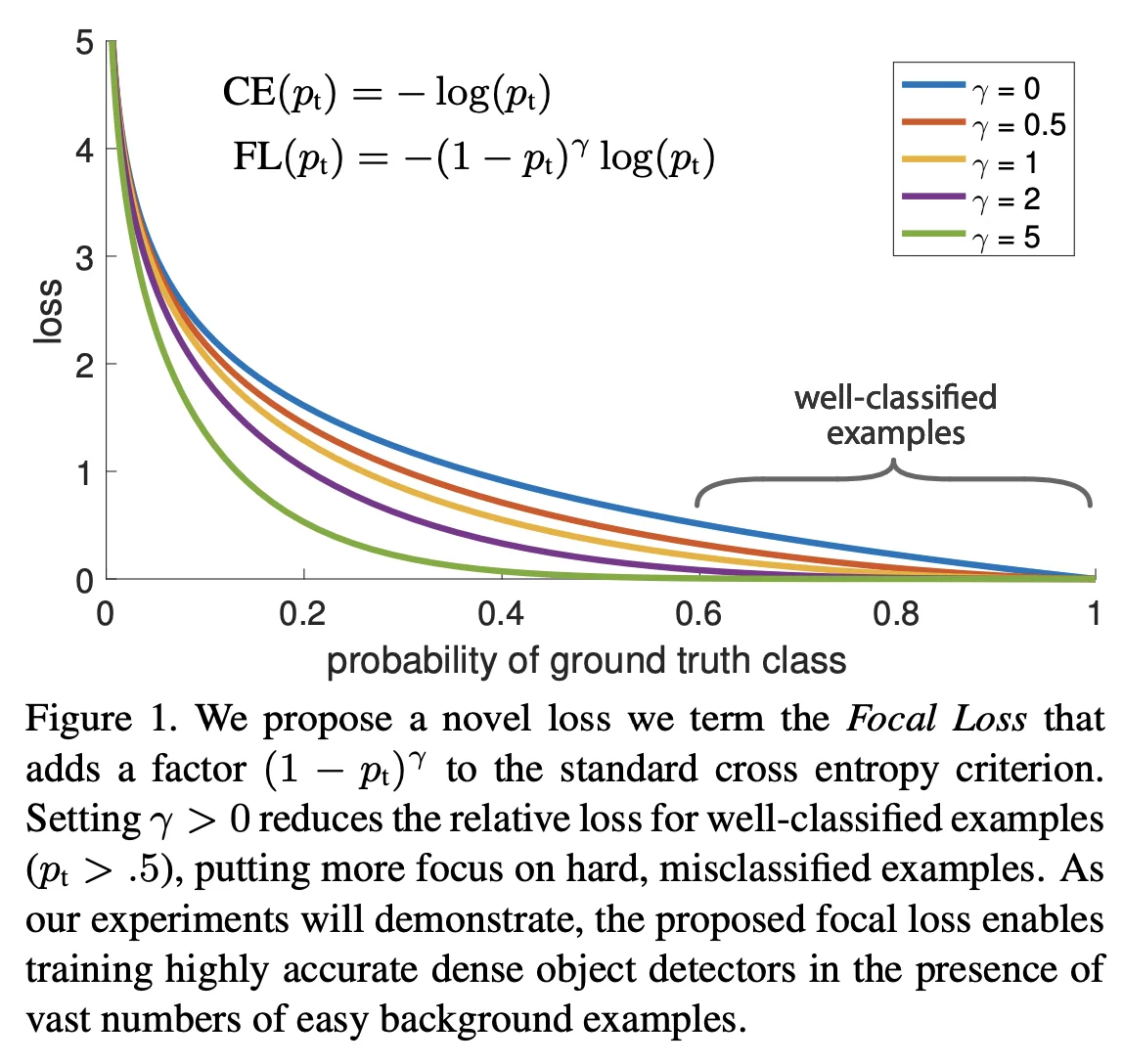

14.4.3 Focal Loss: Addressing Class Imbalance

RetinaNet introduced the focal loss to tackle the severe class imbalance inherent in one-stage detectors. Instead of resorting to heuristic sampling or hard-negative mining, focal loss modifies the standard cross-entropy (CE) loss by down-weighting the loss contribution of well-classified examples, thereby shifting the model’s focus toward hard, misclassified examples.

The focal loss is defined as:

\[ FL(p_t) = - (1 - p_t)^\gamma \log (p_t) \]

where:

- \( p_t \) is the predicted probability for the ground-truth class.

- \( \gamma \) is the tunable focusing parameter.

For comparison, the standard cross-entropy loss is:

\[ CE(p_t) = -\log (p_t) \]

By introducing the modulating factor \((1-p_t)^\gamma \), the focal loss reduces the loss for examples that are already well-classified (i.e., when \( p_t \) is high). For instance, with \(\gamma = 2\):

- If \( p_t = 0.9 \), then \((1-0.9)^2 = 0.01\), and the loss becomes approximately \(0.01 \times -\log (0.9) \approx 0.01 \times 0.105 = 0.00105\). In contrast, the standard CE loss would be about 0.105.

- If \( p_t = 0.5 \), then \((1-0.5)^2 = 0.25\), and the loss is \(0.25 \times -\log (0.5) \approx 0.25 \times 0.693 = 0.173\).

- If \( p_t = 0.2 \), then \((1-0.2)^2 = 0.64\), and the loss is \(0.64 \times -\log (0.2) \approx 0.64 \times 1.609 = 1.029\).

These examples illustrate that as the prediction confidence \( p_t \) increases (i.e., for easy examples), the modulating factor quickly shrinks the loss, allowing the model to focus its learning capacity on the hard examples where \( p_t \) is lower.

An \(\alpha \)-balanced variant of the focal loss can further address class imbalance by assigning different weights to positive and negative examples:

\[ FL(p_t) = -\alpha _t (1 - p_t)^\gamma \log (p_t) \]

Here, \(\alpha _t\) is chosen to down-weight the loss for the dominant class (usually the background). In practice, selecting \(\gamma = 2\) and an appropriate \(\alpha \) (e.g., 0.25) has been shown to yield robust results.

In summary, focal loss is a key innovation in RetinaNet that directly addresses class imbalance by dynamically down-weighting the loss from easy examples. This enables training a dense one-stage detector effectively without resorting to complex sampling heuristics, ultimately achieving state-of-the-art accuracy while maintaining fast inference speeds.

14.4.4 RetinaNet Architecture and Pipeline

Backbone and Neck (FPN) RetinaNet uses a standard ImageNet–pretrained backbone (e.g., ResNet-50/101 or ResNeXt-101) to produce a hierarchy of feature maps (commonly denoted \(C_3,C_4,C_5\)). Early backbone stages are high-resolution but semantically weaker; late stages are semantically strong but very coarse. The Feature Pyramid Network (FPN) is a lightweight top-down pathway with lateral connections that fuses these signals to create a new set of semantically strong, multi-scale maps \(P_3,\dots ,P_7\). Concretely:

- \(P_5\) is obtained from \(C_5\) by a \(1{\times }1\) lateral conv; \(P_4\) and \(P_3\) are formed by upsampling the higher level and adding a lateral projection from \(C_4\) and \(C_3\) respectively, followed by a \(3{\times }3\) conv for smoothing.

- \(P_6\) and \(P_7\) extend the pyramid for very large objects via stride-2 \(3{\times }3\) convs (e.g., \(P_6\) directly from \(C_5\), then \(P_7\) from \(P_6\) with a ReLU in between).

Each level has a well-defined stride relative to the input image, typically \(\{8,16,32,64,128\}\) pixels for \(P_3\)–\(P_7\). Thus, one spatial location at \(P_\ell \) summarizes roughly a \(\mbox{stride}_\ell \times \mbox{stride}_\ell \) patch of the input. High-resolution \(P_3\) captures small objects; low-resolution \(P_6,P_7\) capture large ones and global context.

Dense Anchors (per FPN level) Detection is made dense by tiling anchors—predefined box prototypes—at every spatial location of every pyramid level. RetinaNet assigns each level a base side length \[ s_\ell \in \{32,64,128,256,512\}\quad \mbox{for}\quad P_3,\dots ,P_7, \] so that level \(P_\ell \) is responsible for objects whose side lengths are \(\mathcal {O}(s_\ell )\). To cover shapes and nearby scales without exploding the search space, \(\mathbf {A=9}\) anchors are placed per location by combining \[ \mbox{aspect ratios } r \in \{1/2,\,1,\,2\}\quad \mbox{and}\quad \mbox{in-octave scales } m_k \in \{2^{0},\,2^{1/3},\,2^{2/3}\}. \] Given \((s_\ell ,m_k,r)\), an anchor’s width and height are \[ w_{\ell ,k,r} = s_\ell \, m_k\, \sqrt {r},\qquad h_{\ell ,k,r} = s_\ell \, m_k\, / \sqrt {r}, \] which preserves the anchor’s area near \((s_\ell m_k)^2\) while adjusting its shape by \(r=w/h\).

Why fractional scales like \(2^{1/3}\)? RetinaNet partitions each octave (a doubling of size) into three equal steps in \(\log _2\) space. The multiplicative ratio between adjacent scales is \(2^{1/3}\approx 1.26\). This yields anchors that (i) are evenly spaced in scale (no “holes” between \(32\) and \(64\), etc.), (ii) avoid redundant near-duplicates that arise with coarse integer jumps, and (iii) keep coverage smooth across object sizes. Intuitively, if an object’s true size lies between powers of two, one of the three in-octave scales will land close enough that the regressor only needs to make a small, stable adjustment.

Across \(P_3\)–\(P_7\), this construction spans effective side lengths from roughly \(32\) to \(512\) pixels (and intermediate in-octave values), producing on the order of \(10^5\) anchors per image—ample coverage for size and shape, while remaining efficient due to shared convolutions over the pyramid.

RetinaNet attaches two small, fully convolutional “heads” to every FPN level; their weights are shared across levels for parameter efficiency (the two heads do not share weights with each other):

- Classification head: a subnetwork of four \(3\times 3\) conv layers with 256 channels (each followed by ReLU), ending in a \(3\times 3\) conv that outputs \(A\times C\) per-class logits per spatial location. A sigmoid is applied independently to each of the \(C\) classes (no softmax over classes), which pairs naturally with the Focal Loss.

- Box regression head: an identically shaped subnetwork that ends in \(A\times 4\) outputs per location, parameterizing relative offsets \((t_x,t_y,t_w,t_h)\) from the anchor.

Bias initialization for stability. To counter the extreme initial imbalance, RetinaNet initializes the final classification-layer bias to \[ b=-\log \!\left (\frac {1-\pi }{\pi }\right ),\quad \pi =0.01, \] so the network starts with a low prior probability for foreground, reducing spurious early gradients from the vast background set.

Inference (single pass) All FPN levels are processed in parallel, producing a total of \(\mathcal {O}(10^5)\) anchor predictions per image. After a low score threshold (e.g., 0.05), RetinaNet applies per-class NMS (e.g., IoU 0.5) and keeps the top-\(K\) detections (e.g., \(K{=}100\)).

Why this works (and what was missing before) Architecturally, RetinaNet is deliberately simple: it keeps the RPN’s efficient, fully convolutional template but upgrades to multi-class classification and full box refinement over a feature pyramid. The historical blocker for single-stage accuracy was not the architecture but the extreme class imbalance inherent to dense prediction. RetinaNet’s breakthrough is to pair this streamlined design with the Focal Loss, which down-weights the flood of easy negatives so the classifier learns from scarce positives and hard examples. The result is two-stage–level accuracy with single-stage speed.

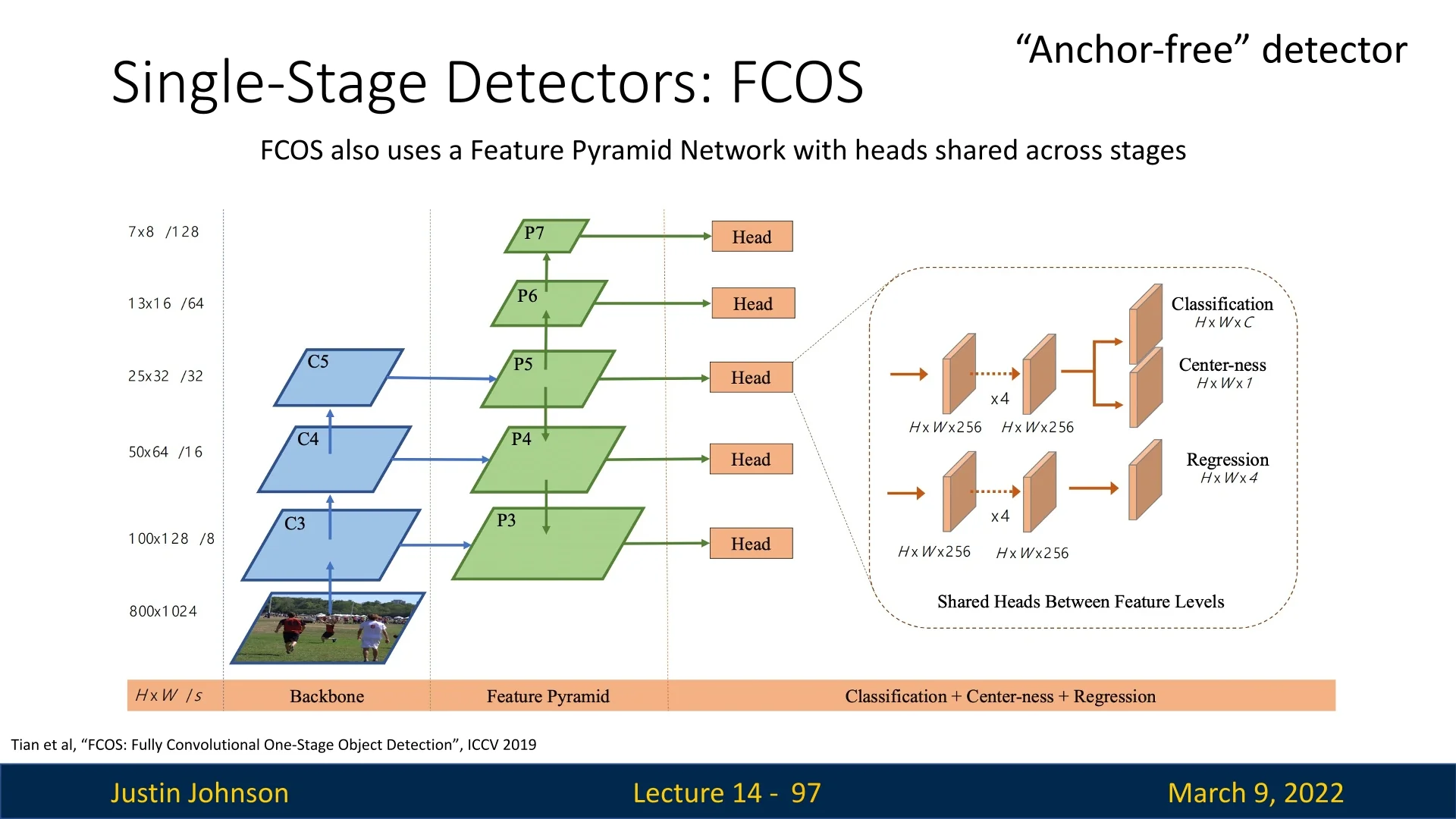

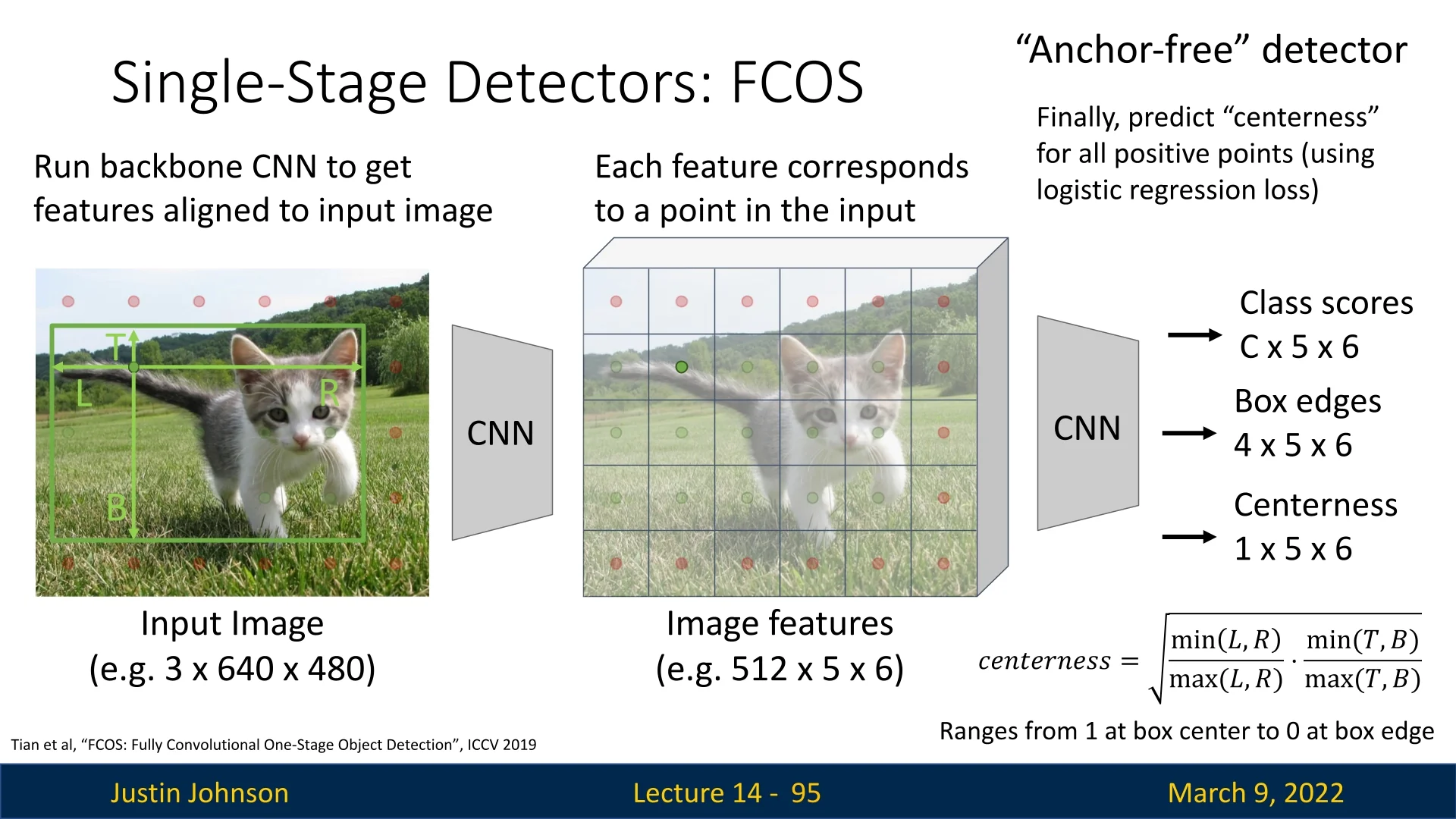

14.5 FCOS: An Anchor-Free, Fully Convolutional Detector

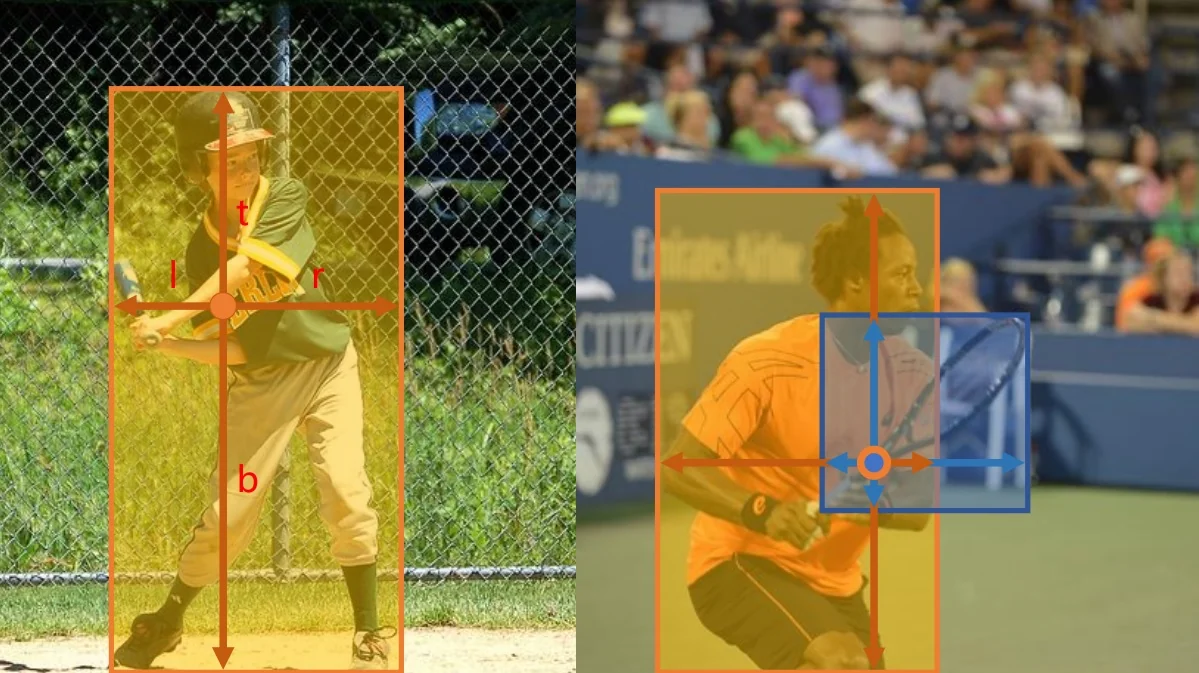

FCOS [617] is an anchor-free one-stage detector that casts detection as a dense, per-pixel prediction problem. Instead of matching ground-truth boxes to a large, hand-designed set of anchors (sizes, aspect ratios, and assignment rules), every spatial location on a feature map can vote for an object by predicting its class and the distances from that location to the four sides of the object’s box. This removes anchor hyperparameters and simplifies both the design and the training pipeline.

14.5.1 Core Pipeline and Supervision

Backbone and Feature Maps A backbone (e.g., ResNet) with FPN produces a pyramid of feature maps \(\{P_3,\dots ,P_7\}\). A location \((x,y)\) on a pyramid level with stride \(s\) corresponds to an input coordinate \(\tilde {x}=x\cdot s+\delta ,\ \tilde {y}=y\cdot s+\delta \) (with a fixed offset \(\delta \) such as \(s/2\)).

Positive/Negative Assignment For each feature-map location, FCOS checks whether its mapped coordinate \((\tilde {x},\tilde {y})\) lies inside any ground-truth box \(B=(x_0,y_0,x_1,y_1)\). If not, the location is negative (background). If yes, it is positive and is assigned to (i) that class and (ii) a single box, chosen as the smallest-area box among those covering \((\tilde {x},\tilde {y})\) to favor supervision from small, harder objects.

Distance-From-Point Regression Targets For a positive location, regression targets are the distances to the four sides of its assigned box: \[ l^\ast =\tilde {x}-x_0,\quad t^\ast =\tilde {y}-y_0,\quad r^\ast =x_1-\tilde {x},\quad b^\ast =y_1-\tilde {y}. \] At inference, predicted distances \((l,t,r,b)\) are converted back to a box \((\tilde {x}-l,\ \tilde {y}-t,\ \tilde {x}+r,\ \tilde {y}+b)\).

14.5.2 Multi-Level Prediction with FPN

As in RetinaNet, FCOS uses FPN to divide the problem by object size rather than by anchor scale. Each level is responsible for a range of object sizes (typical choices): \[ \begin {aligned} P_3 &: (0,64]\ \mbox{pixels},\quad P_4 &: (64,128],\quad P_5 &: (128,256],\\ P_6 &: (256,512],\quad P_7 &: (512,\infty ) \end {aligned} \] This assignment reduces label ambiguity across scales and lets a single set of prediction heads operate reliably at all pyramid levels.

14.5.3 Centerness: Definition, Role, and Intuition

Why Centerness Any location inside a ground-truth box is a valid positive, but locations near the edges tend to yield lower-quality boxes: one or more distances \((l^\ast ,t^\ast ,r^\ast ,b^\ast )\) are small on one side and large on the other, making the regression ill-conditioned. FCOS introduces a third head that predicts a centerness score to quantify how central a location is w.r.t. its assigned object.

Target and Shape The centerness target is \[ \mbox{centerness}^\ast = \sqrt { \frac {\min (l^\ast ,r^\ast )}{\max (l^\ast ,r^\ast )} \cdot \frac {\min (t^\ast ,b^\ast )}{\max (t^\ast ,b^\ast )} }. \] It is the geometric mean of horizontal and vertical “balancedness.” At the exact center, \(l^\ast =r^\ast \) and \(t^\ast =b^\ast \), so \(\mbox{centerness}^\ast =1\). As a point drifts toward an edge on either axis, the corresponding ratio shrinks toward \(0\), and so does the score. The square root moderates the decay so that moderately off-center locations are not over-penalized.

- Training: The centerness head is trained with a binary cross-entropy loss to regress \(\mbox{centerness}^\ast \). In addition, FCOS weights the localization loss of a positive location by \(\mbox{centerness}^\ast \), down-weighting inherently low-quality positives (near edges) during box regression.

- Inference: The final detection confidence is \(\mbox{score} = \mbox{class_prob} \times \mbox{centerness}\). This suppresses spurious boxes predicted from peripheral locations without requiring extra post-processing heuristics.

14.5.4 Localization with IoU Loss

Computation in Distance Parameterization Let the predicted distances be \((l,t,r,b)\) and the targets \((l^\ast ,t^\ast ,r^\ast ,b^\ast )\) for the same positive location. Define predicted and target areas \[ A_p=(l+r)(t+b),\qquad A_g=(l^\ast +r^\ast )(t^\ast +b^\ast ). \] Because both boxes are anchored at the same location, the intersection width and height are \[ w_I=\min (l,l^\ast )+\min (r,r^\ast ),\qquad h_I=\min (t,t^\ast )+\min (b,b^\ast ), \] and the intersection area is \(A_I=w_I\cdot h_I\). The IoU is \[ \mbox{IoU}=\frac {A_I}{A_p+A_g-A_I},\qquad L_{\mbox{reg}}=-\log (\mbox{IoU})\ \ \mbox{or}\ \ 1-\mbox{IoU}. \]

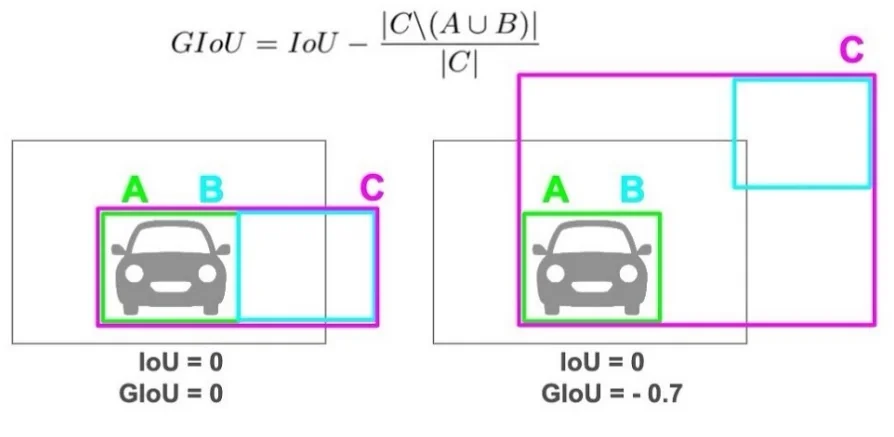

Why IoU, not \(L_1\) IoU loss is scale-invariant and holistic: it couples all four distances to maximize overlap. In contrast, \(L_1\)/smooth-\(L_1\) penalize each side independently and over-weight large boxes. Variants such as GIoU/DIoU/CIoU can further stabilize optimization, but vanilla IoU already yields strong localization in FCOS.

14.5.5 Multi-Task Objective and Training Scheme

Per image, let \(\mathcal {P}\) be the set of positive locations across all pyramid levels and \(N_+\!=\!|\mathcal {P}|\) (with a small \(\epsilon \) to avoid division by zero). FCOS minimizes \[ L_{\mbox{total}} =\underbrace {L_{\mbox{cls}}}_{\mbox{focal, pos+neg}} +\lambda _{\mbox{reg}} \underbrace {\frac {1}{N_+}\sum _{i\in \mathcal {P}}\mbox{centerness}_i^\ast \,L_{\mbox{reg},i}}_{\mbox{IoU on positives, weighted by } \mbox{centerness}^\ast } +\lambda _{\mbox{ctr}} \underbrace {\frac {1}{N_+}\sum _{i\in \mathcal {P}} \mbox{BCE}(\hat {c}_i,\mbox{centerness}_i^\ast )}_{\mbox{centerness head on positives}}, \] where:

- \(L_{\mbox{cls}}\) is the Focal Loss over all locations (positives and negatives), mitigating extreme foreground–background imbalance

- \(L_{\mbox{reg}}\) is the IoU loss in the distance parameterization for positives only

- The regression term is weighted by \(\mbox{centerness}^\ast \) to de-emphasize inherently low-quality edge positives

- \(\lambda _{\mbox{reg}},\lambda _{\mbox{ctr}}\) balance localization and centerness terms; practical defaults often set them to \(1\)

At inference, the per-class probability is multiplied by the predicted centerness before NMS. Thus, focal loss addresses class imbalance, IoU loss optimizes overlap quality, and centerness calibrates both training weights (for localization) and test-time confidences.

14.5.6 Inference

Single forward pass over the FPN yields class scores, distances, and centerness for every location. Predictions with low class score are filtered; remaining scores are multiplied by centerness; distances are converted to boxes; per-class NMS produces final detections.

14.5.7 Advantages of FCOS

FCOS introduces several improvements over anchor-based detectors:

- Simpler Design: Eliminates the need for anchor boxes, reducing hyper-parameter tuning.

- Computational Efficiency: Avoids anchor box computations, reducing memory and processing overhead.

- Better Foreground Utilization: Unlike anchor-based methods, which only consider a subset of anchors, FCOS treats every feature map location inside a ground-truth box as a positive sample.

- Improved Detection Quality: The centerness mechanism suppresses low-quality predictions, reducing false positives.

By leveraging fully convolutional architectures and eliminating the complexities of anchor boxes, FCOS provides a simple yet powerful alternative to traditional object detection methods.

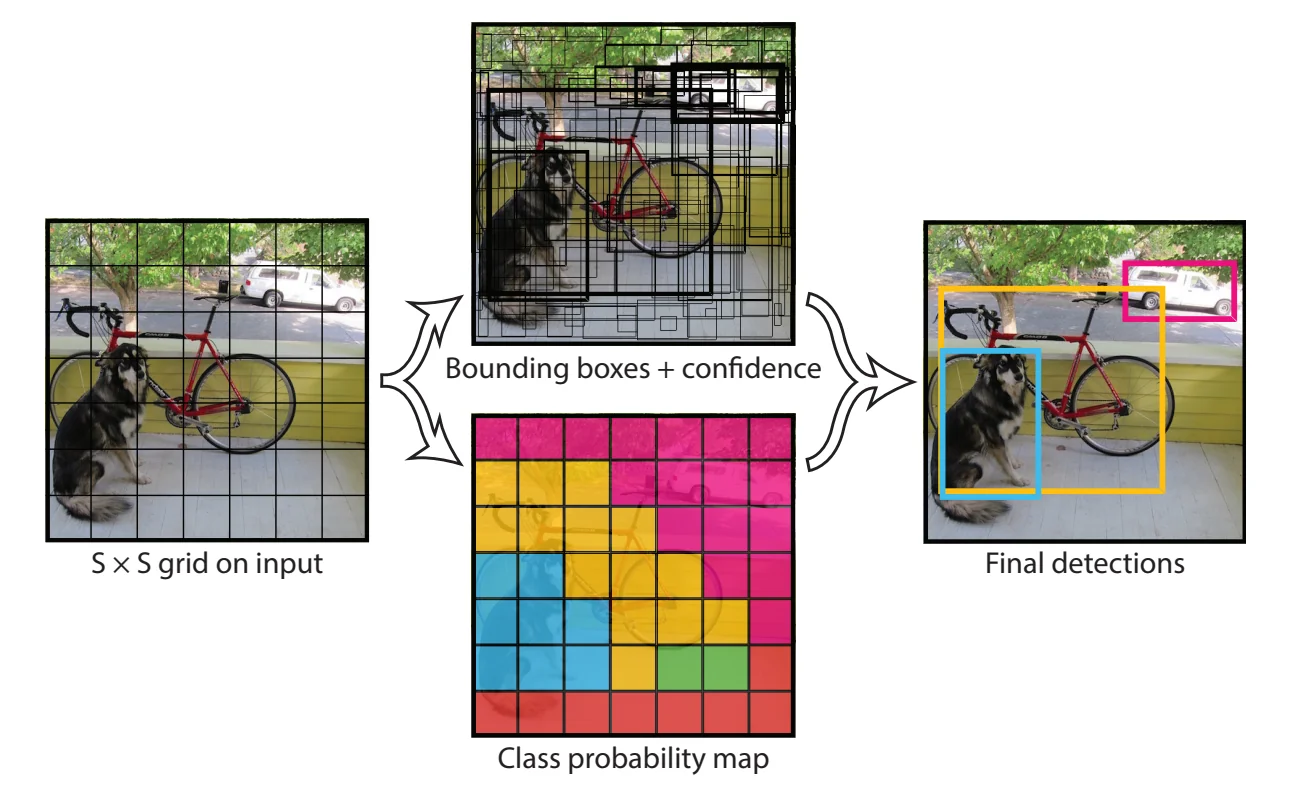

Enrichment 14.6: YOLO - You Only Look Once

Enrichment 14.6.1: Background

YOLO (You Only Look Once) revolutionized object detection by treating it as a single regression problem, enabling real-time detection without requiring multiple passes over an image.

First introduced by Redmon et al. in [518], YOLO has continuously evolved (from YOLOv1 to more advanced versions) by improving accuracy while maintaining real-time performance. Its success stems from:

- Speed: YOLO’s one-pass approach makes it significantly faster than two-stage detectors, enabling applications in autonomous driving, surveillance, and real-time video analysis.

- Global Reasoning: By processing the entire image at once, YOLO reduces false positives from overlapping region proposals and makes more context-aware predictions.

Thanks to these advantages, YOLO remains one of the most widely used object detection frameworks, consistently setting new benchmarks for real-time applications.

Enrichment 14.6.2: Step-by-Step: How YOLOv1 Processes an Input Image

YOLOv1 (You Only Look Once) is a single-stage object detector that predicts bounding boxes and class probabilities in one unified forward pass. Below, we outline how YOLOv1 processes an image from start to finish.

1. Input Image and Preprocessing

- Dimensions: YOLOv1 typically expects an image resized to \(448\times 448\).

- Normalization: In practice, pixel values may be scaled (e.g., to \([0,1]\) or \([-1,1]\)) to help training stability.

- This preprocessed image is fed into the network as a PyTorch Tensor

of shape

\(\bigl [\mbox{batch_size}, 3, 448, 448\bigr ]\).

2. Feature Extraction (DarkNet + Additional Convolution Layers) YOLOv1 is composed of:

- 1.

- DarkNet, which produces a high-level feature map from the input image. DarkNet is a series of convolutional layers interspersed with activations (Leaky ReLU) and sometimes batch normalization.

- 2.

- Additional convolution layers that further refine the 1024-channel output of DarkNet.

Eventually, these convolutions yield a feature map of shape \(\bigl [\mbox{batch_size}, 1024, S, S\bigr ]\), where S is grid dimension, a hyperparameter that fits our feature extraction process (in YOLOv1, \(S=7\)). Hence, YOLOv1 divides the image conceptually into a \(7\times 7\) grid.

3. Flattening and Fully Connected Layers After the final convolutional layer, the 7\(\times \)7\(\times \)1024 feature map is:

- Flattened into a 1D vector of length \(7 \times 7 \times 1024 = 50176\).

- Passed into a Linear(50176, 4096) layer, a Leaky ReLU, and a dropout layer.

-

Finally, passed into a linear output layer of size \(S \times S \times (5B + C)\), where:

- \(S=7\) is the number of grid cells per dimension.

- \(B=2\) is the number of bounding boxes each cell predicts.

- \(C=20\) is the number of classes (for the PASCAL VOC Dataset).

This yields an output tensor of shape: \[ \bigl [\mbox{batch_size},\,7,\,7,\,(5 \times 2 + 20)\bigr ] = \bigl [\mbox{batch_size},\,7,\,7,\,30\bigr ]. \] The final layer is linear: it produces real-valued outputs that are trained, via a sum-of-squared-errors loss, to approximate normalized targets (e.g., coordinates and confidences in \([0,1]\)).

4. Understanding the Output Format Concretely, each cell’s part of the final output includes:

- 1.

- \(\mathbf {(x, y)}\): Center offsets for box 1 within the cell, in \([0,1]\).

- 2.

- \(\mathbf {w, h}\): Width and height for box 1, also in \([0,1]\).

- 3.

- \(\mbox{confidence}\): A single scalar in \([0,1]\) for how likely the predicted box is valid (the bounding box overlaps an object).

- 4.

- The same 5 parameters for box 2 (\(x, y, w, h, \mbox{confidence}\)).

- 5.

- \(\mathbf {C}\) class probabilities for the cell, also in \([0,1]\).

5. Parameterization and Normalization Although the final layer is linear, YOLOv1 parametrizes its targets so that most predicted quantities naturally lie in \([0,1]\):

- \(\hat {x}, \hat {y}\) are trained to represent the center of the box relative to the grid cell that predicts it, with targets in \([0,1]\). At inference time, we convert them to absolute image coordinates using the cell indices \((c_x, c_y)\) and the grid size \(S\).

- \(\hat {w}, \hat {h}\) are trained to represent the box width and height relative to the full image size, again with targets in \([0,1]\). The loss uses \(\sqrt {w}\) and \(\sqrt {h}\) to emphasize errors on small boxes.

- The confidence output for each box is trained to regress to \[ C = P(\mbox{object}) \cdot \mathrm {IoU}(\mbox{box}, \mbox{gt}) \in [0,1], \] where \(\mathrm {IoU}\) is the intersection-over-union with the ground-truth box.

- The class probabilities are conditional probabilities \(P(\mbox{class}_c \mid \mbox{object})\) at the cell level, with targets given by one-hot vectors over the \(C\) classes.