Lecture 23: 3D vision

23.1 Introduction to 3D Perception from 2D Images

In this part of the course we explore how deep neural networks can process and predict 3D information from various inputs, particularly focusing on inferring three-dimensional structures from two-dimensional images. Unlike classical computer vision tasks that operate strictly in 2D, 3D vision tasks aim to reconstruct or understand the three-dimensional structure of the world. These tasks are essential in applications ranging from autonomous navigation to augmented reality.

23.1.1 Core Tasks in 3D Vision

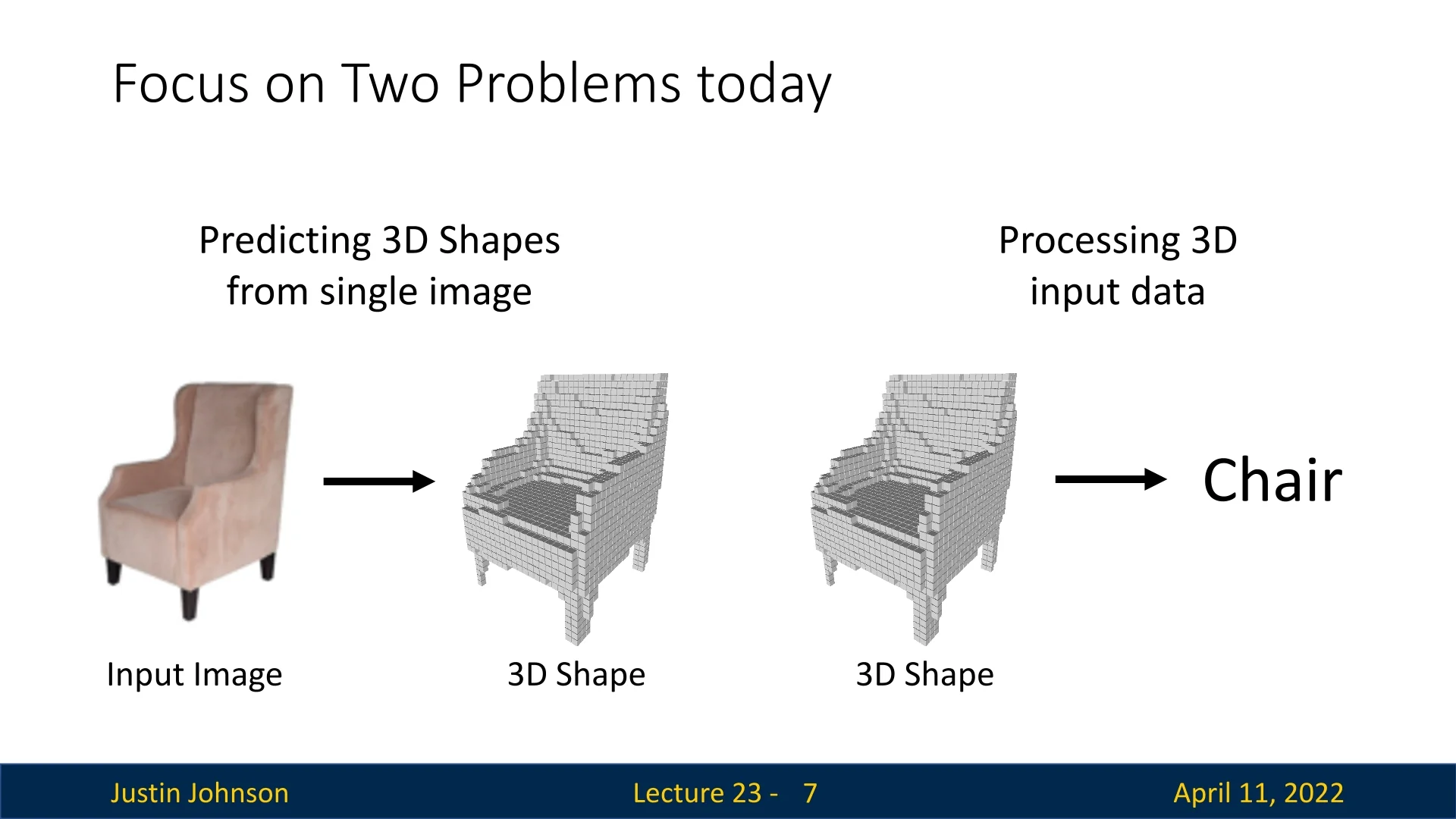

In this chapter, our main focus will be on two core 3D vision tasks:

- 1.

- 3D Shape Prediction: Given a single 2D image (e.g., of an armchair), the model predicts a corresponding 3D structure, such as a voxel grid that represents the shape of the object. This task is inherently ill-posed due to the loss of depth information in the 2D projection.

- 2.

- 3D-Based Classification: Given a 3D representation (e.g., a voxel grid), the model predicts the semantic class of the object (e.g., “armchair”), showing understanding from structural geometry.

Beyond these core problems, 3D vision encompasses a broad range of challenges such as motion estimation from depth, simultaneous localization and mapping (SLAM), multi-view reconstruction, and more. Importantly, due to the strong geometric structure of the 3D world, many classical vision algorithms (e.g., stereo triangulation) remain highly relevant and are often integrated with or benchmarked against learning-based methods.

23.1.2 3D Representations

A variety of representations can capture the geometry of 3D objects. While differing in format, all serve the common goal of describing shape and structure in three dimensions:

- Depth Map: A 2D grid where each pixel stores the distance (in meters) from the camera to the nearest surface point along the ray passing through that pixel. Captured by RGB-D sensors (e.g., Microsoft Kinect), these are often called 2.5D images since they only encode visible surfaces, not occluded regions.

- Voxel Grid: A 3D array of binary or real-valued occupancies representing whether a volume element (voxel) is occupied.

- Point Cloud: A sparse set of 3D points capturing surface geometry.

- Mesh: A polygonal surface composed of vertices, edges, and faces—typically used in graphics.

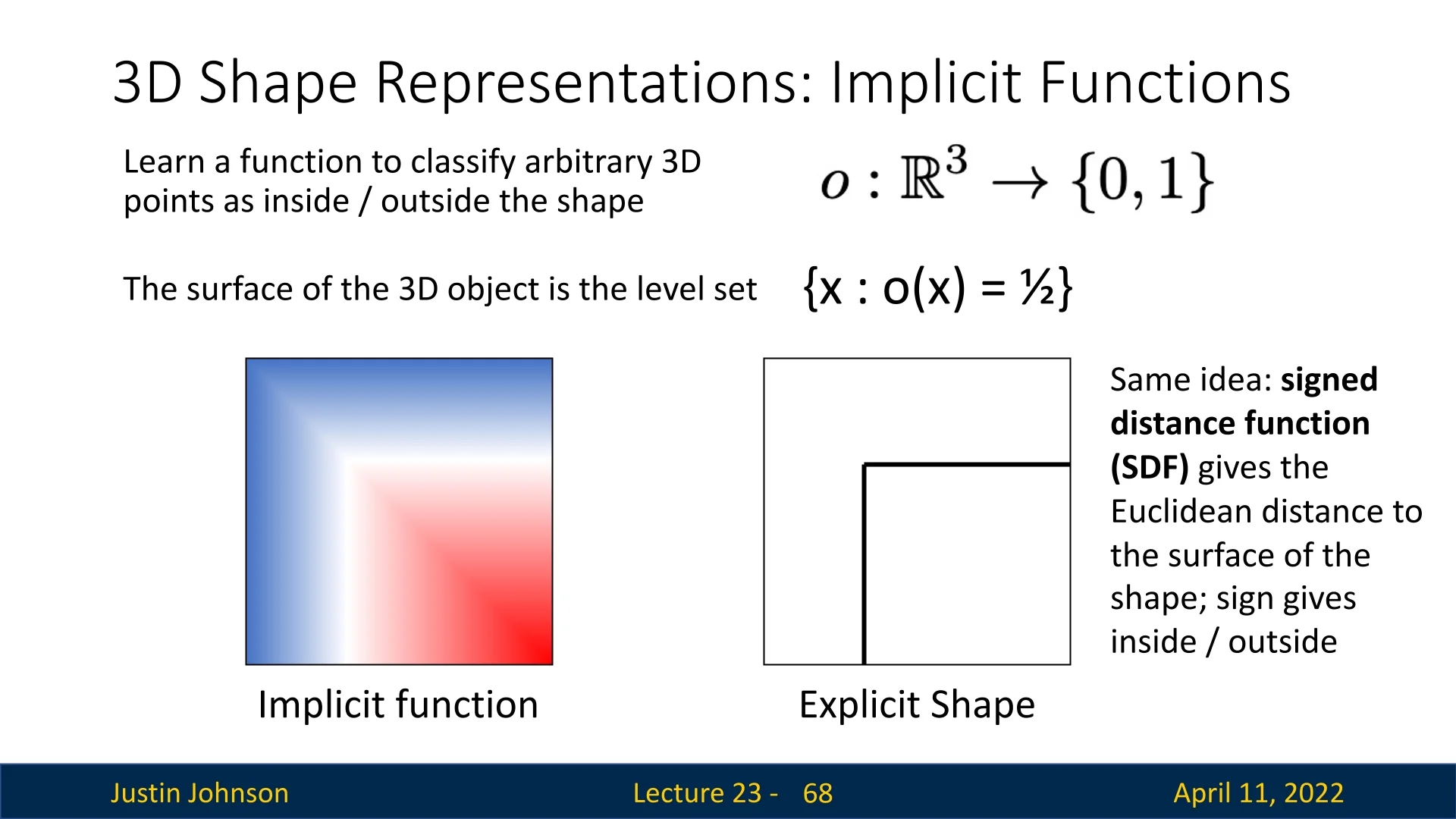

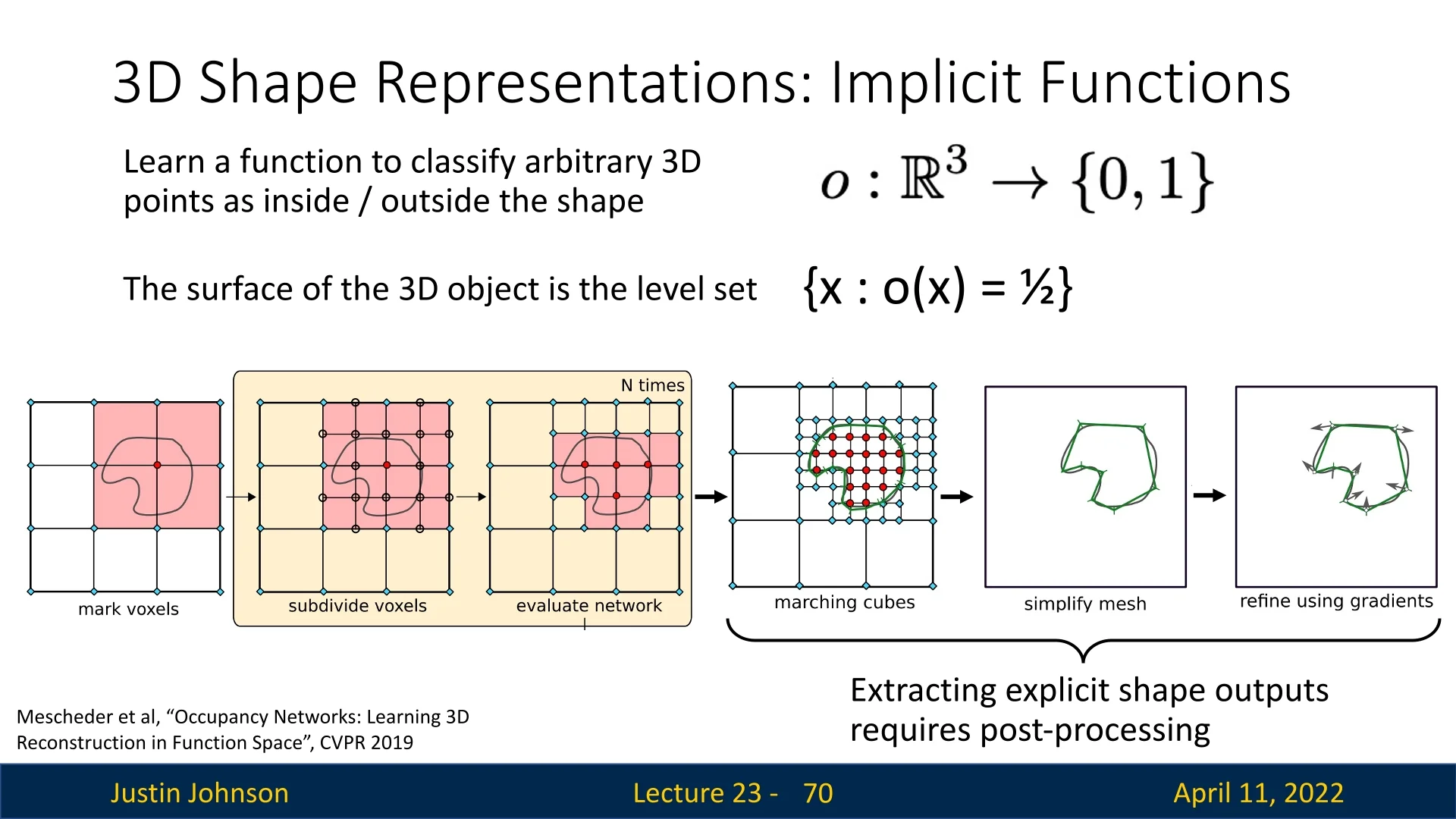

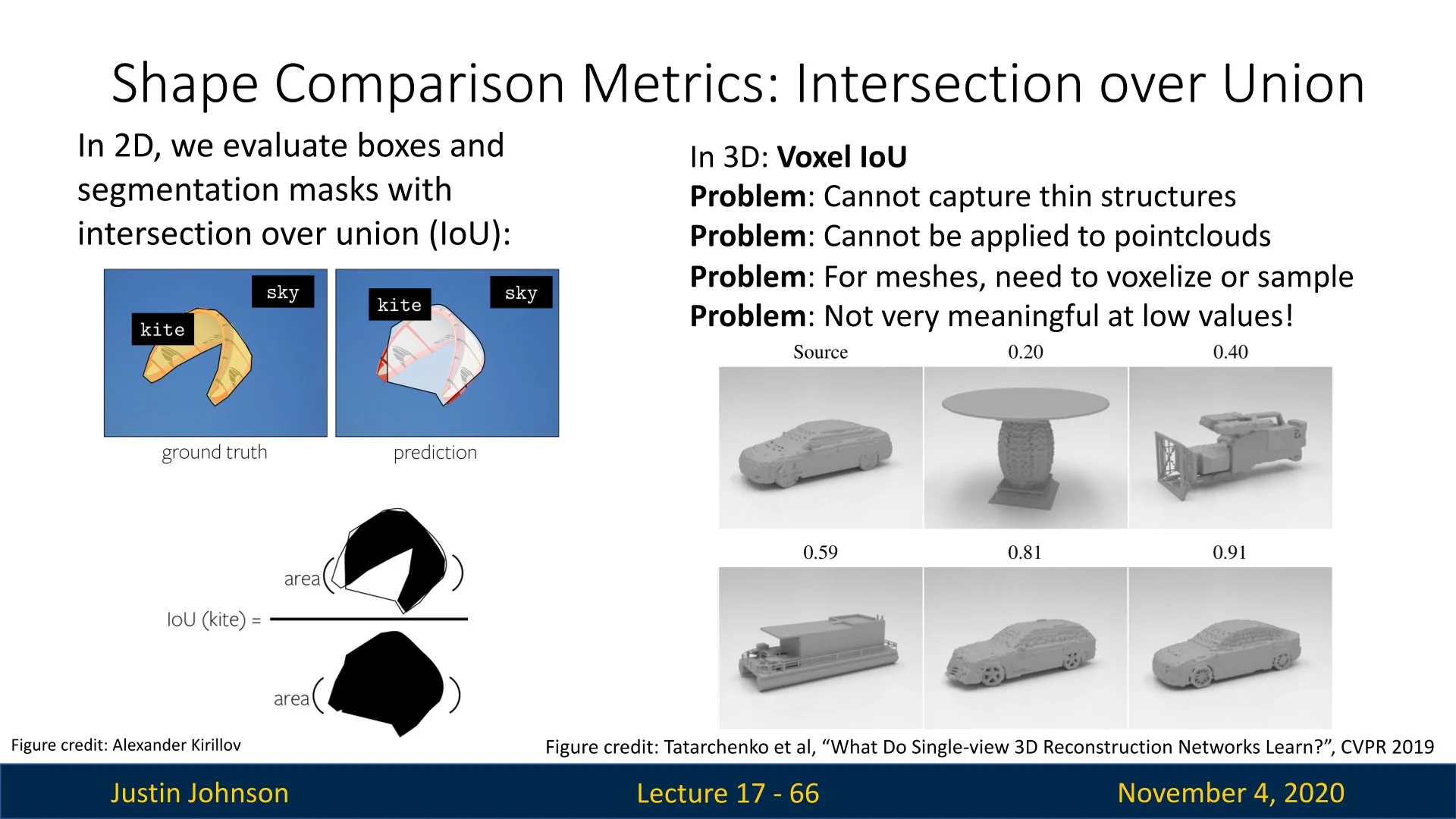

- Implicit Surface: A continuous function (e.g., signed distance function) where the zero-level set defines the surface of the object.

Despite differing computational properties and storage formats, all these representations aim to capture the same underlying 3D structure.

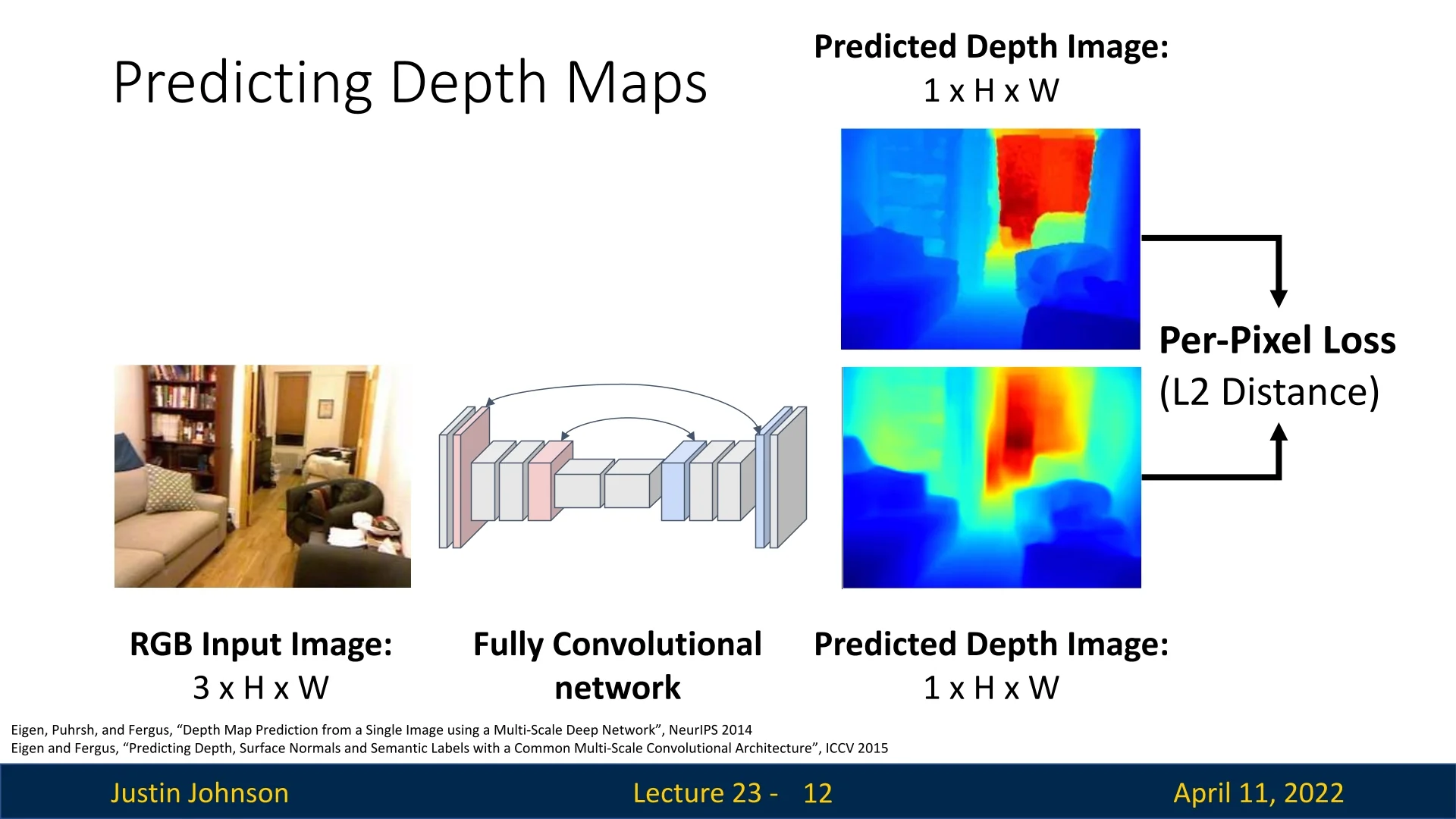

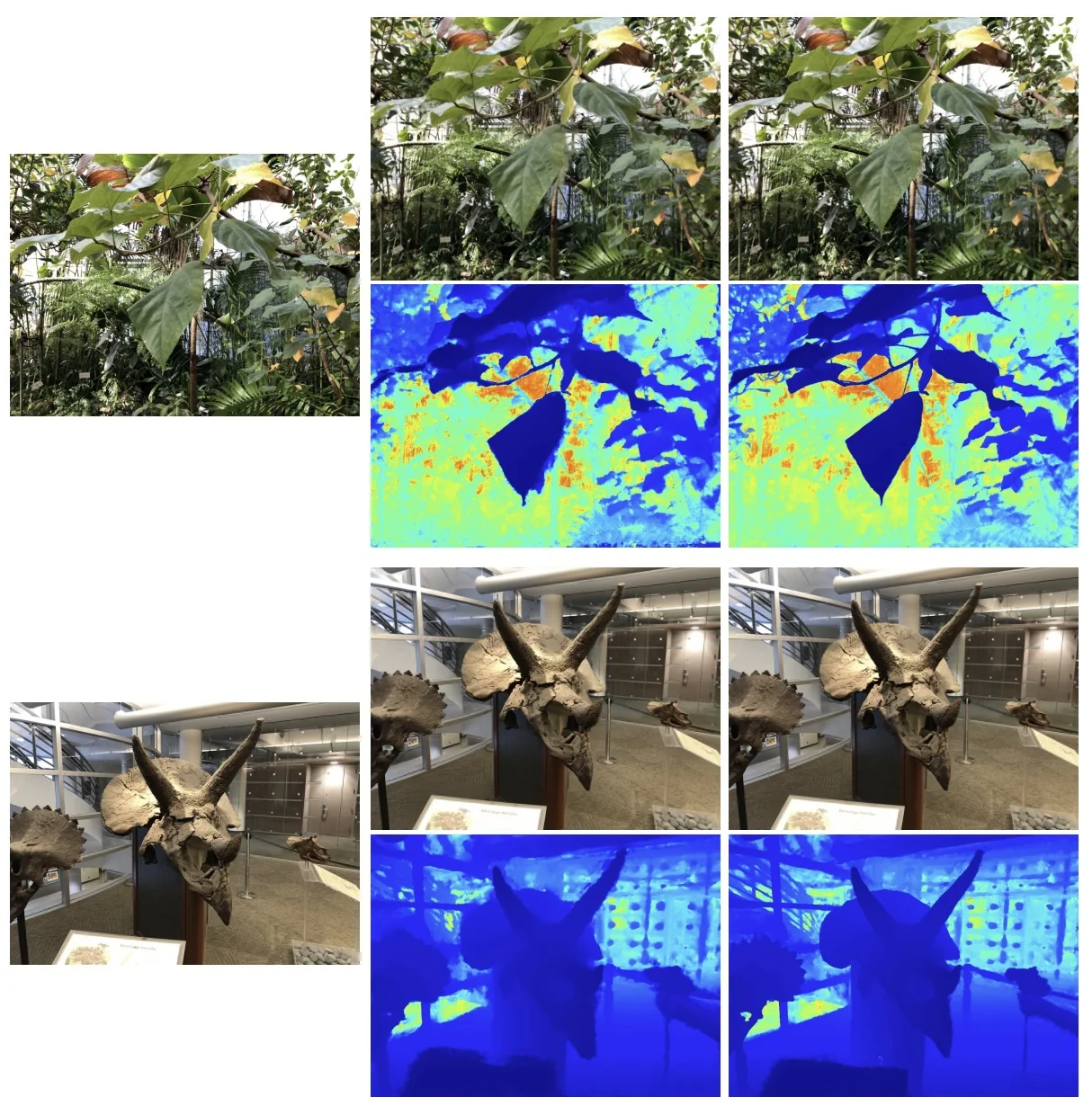

23.2 Predicting Depth Maps from RGB Images

One of the most accessible and widely studied 3D vision tasks is estimating a dense depth map from a single RGB image. This process, known as monocular depth estimation, aims to assign a depth value to each pixel, producing a 2.5D representation of scene geometry from a monocular input. The task is fundamentally ill-posed, as multiple 3D scenes can correspond to the same 2D projection, making monocular depth estimation a challenging problem that requires strong visual priors.

A common and effective architectural design for this task is the fully convolutional encoder-decoder network, which is well-suited to dense prediction tasks. These models process an input image through an encoder to extract semantically rich features and subsequently reconstruct a dense depth map via a decoder that upsamples these features to the input resolution. The fully convolutional nature of this pipeline ensures that the spatial correspondence between input pixels and output predictions is preserved, enabling pixel-aligned depth estimation.

The encoder typically consists of a convolutional backbone (e.g., ResNet) pretrained on large-scale classification datasets like ImageNet. Through successive layers of strided convolutions, the encoder compresses the spatial resolution of the input while increasing the semantic abstraction and receptive field. This enables the network to aggregate both local texture and global scene layout, capturing information necessary for reasoning about object scale, occlusion, and perspective.

The decoder reverses this spatial compression, gradually upsampling the feature maps to predict a dense depth map. In U-Net-style architectures, skip connections are employed to concatenate feature maps from early encoder layers with corresponding decoder stages, facilitating the recovery of fine-grained details such as object boundaries and thin structures. This coarse-to-fine decoding strategy is particularly effective in reconciling global context with local spatial accuracy.

Several influential models build upon this framework:

- MiDaS [511] emphasizes generalization across diverse datasets. Later versions of MiDaS replace convolutional encoders with Vision Transformers (ViTs), leveraging global self-attention to capture long-range dependencies and scene-level structure. This shift enables more coherent depth maps, particularly in unfamiliar environments.

- BTS (From Big to Small) [320] enhances the decoder with local planar guidance (LPG) modules. These modules predict local plane parameters at multiple resolutions, guiding the reconstruction of depth maps by assuming piecewise planar geometry—a useful trait we can use for scenes with man-made structures or flat surfaces.

- DPT (Dense Prediction Transformer) [510] combines a ViT encoder with a convolutional decoder, explicitly designed for dense prediction tasks. DPT treats the image as a sequence of patches from the outset, enabling early global context aggregation. The decoder then reconstructs high-resolution outputs while retaining global consistency, resulting in state-of-the-art depth estimation performance on several benchmarks (at the time of publication).

While the architectural choices vary across models, the core principles remain consistent: extract semantically meaningful, globally aware features with the encoder; restore spatial detail and pixelwise correspondence with the decoder. These systems have made monocular depth estimation viable for real-time applications such as AR, robotics, and autonomous navigation, where dense 3D understanding from a single image is both efficient and essential.

Loss Function and the Limitations of Absolute Depth Regression A foundational approach to monocular depth estimation is to directly regress the ground truth depth using a pixel-wise \(\ell _2\) loss:

\[ \mathcal {L}_{\mbox{depth}} = \frac {1}{N} \sum _{i=1}^{N} \left ( d_i - \hat {d}_i \right )^2, \]

where \( d_i \) denotes the ground truth depth and \( \hat {d}_i \) is the predicted depth at pixel \( i \), for a total of \( N \) pixels. This objective treats depth estimation as a supervised regression task, optimizing the per-pixel distance between prediction and annotation.

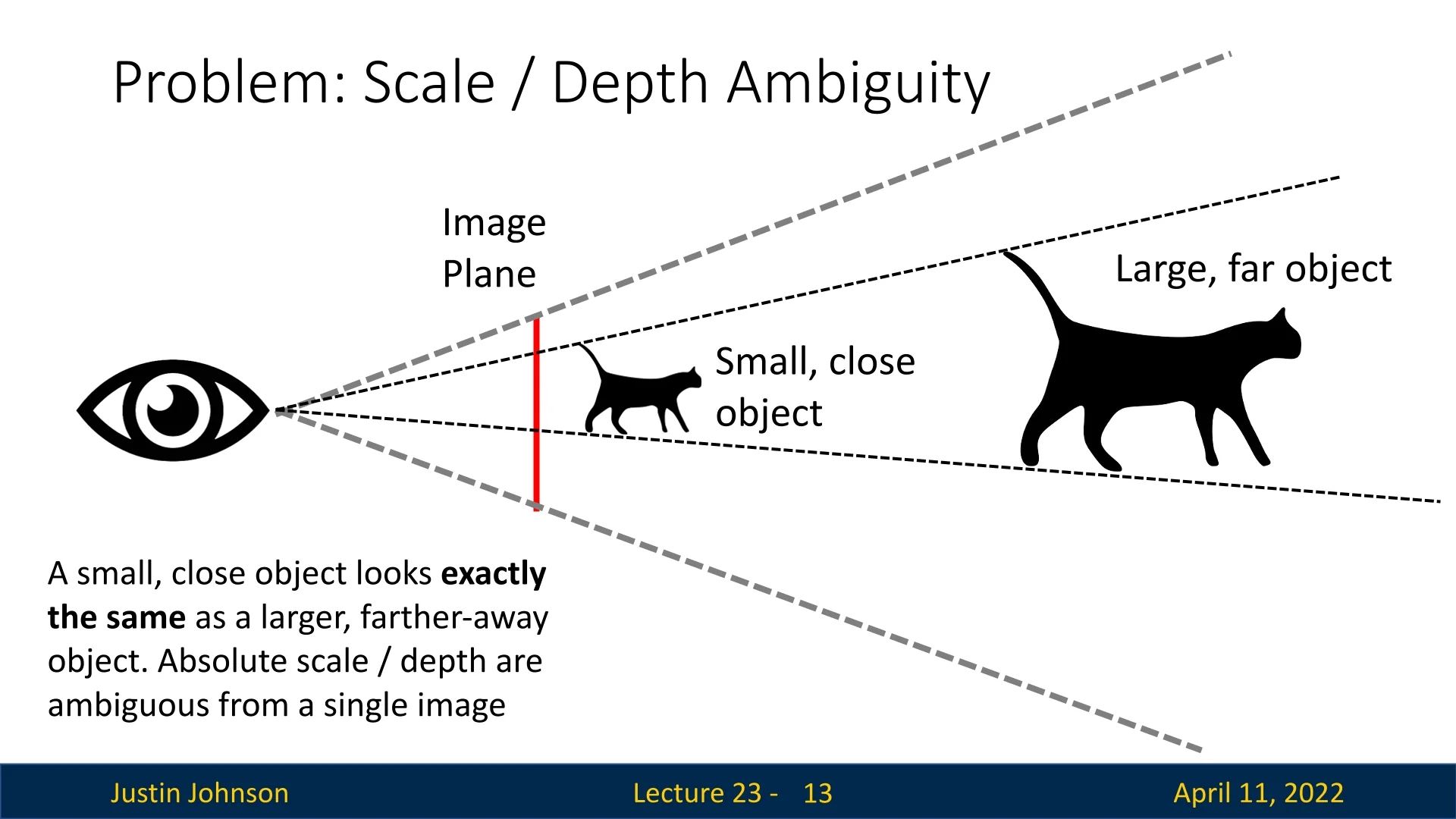

Scale-Depth Ambiguity and the Need for Invariant Losses Despite its simplicity, the \(\ell _2\) loss fails to account for a fundamental limitation in monocular depth estimation: scale-depth ambiguity. Given only a single RGB image, there exist infinitely many 3D scenes that could yield the same 2D projection. For example, a small object placed close to the camera may appear identical in the image to a larger object situated farther away. This ambiguity makes the estimation of absolute scale from monocular input fundamentally ill-posed.

While cues such as object size priors, vanishing points, or scene layout may offer some information, the absolute scale remains ambiguous without auxiliary data. Consequently, modern methods replace or augment the naïve \(\ell _2\) objective with loss functions that are invariant to scale and shift and that emphasize relative structure.

Scale-Invariant Log-Depth Loss Monocular depth estimation suffers from scale-depth ambiguity: an image alone does not reveal whether a small object is nearby or a large object is far away. This ambiguity renders absolute depth supervision fundamentally ill-posed without geometric cues. To address this, [141] proposed a scale-invariant loss that focuses on preserving relative scene structure while remaining agnostic to global depth scale.

Let \( \hat {d}_i \) and \( d_i \) denote the predicted and ground truth depth at pixel \( i \), respectively. Define the log-space residual at each pixel as \[ \delta _i = \log \hat {d}_i - \log d_i = \log \left ( \frac {\hat {d}_i}{d_i} \right ). \] This transforms multiplicative depth errors—such as those caused by an overall scaling mistake—into additive biases in log space. For example, if all predictions are off by a constant factor \( s \), then \( \delta _i = \log s \) for all \( i \).

The scale-invariant loss is given by: \[ \mathcal {L}_{\mbox{SI}} = \frac {1}{n} \sum _{i=1}^n \delta _i^2 - \frac {1}{n^2} \left ( \sum _{i=1}^n \delta _i \right )^2. \] The first term penalizes pixelwise errors in log-depth, while the second term subtracts the squared mean residual. This centering step ensures that uniform log-space errors—i.e., global scaling shifts—do not contribute to the loss. In the case where \( \hat {d}_i = s \cdot d_i \) for all \( i \), we have \( \delta _i = \log s \) and the two terms cancel exactly, yielding zero loss.

Pairwise Interpretation An equivalent expression of the same loss emphasizes its structural nature: \[ \mathcal {L}_{\mbox{SI}} = \frac {1}{n^2} \sum _{i,j} \left [ \left ( \log \hat {d}_i - \log \hat {d}_j \right ) - \left ( \log d_i - \log d_j \right ) \right ]^2. \] Here, the loss is computed over all pixel pairs, enforcing that the difference in predicted log-depth between any two pixels matches the difference in ground truth log-depth. This pairwise comparison naturally preserves the relative depth ordering and ratios across the image, which define the 3D scene structure up to scale.

Weighted Loss for Training In practice, [141] used a weighted variant of the loss to trade off scale sensitivity and structure preservation. The training objective is: \[ \mathcal {L}_{\mbox{train}} = \frac {1}{n} \sum _i \delta _i^2 - \lambda \cdot \frac {1}{n^2} \left ( \sum _i \delta _i \right )^2, \] where \( \lambda \in [0,1] \) determines how strongly the loss penalizes global scale errors. Setting \( \lambda = 0 \) recovers the standard log-MSE, while \( \lambda = 1 \) gives the fully scale-invariant loss. The authors found \( \lambda = 0.5 \) to offer a good balance—preserving global scale roughly while improving structural coherence and visual quality of the depth maps.

Why a Single Global Scale Correction Suffices Monocular images lack metric information, so networks often make consistent global depth errors—predicting all depths as uniformly too large or too small. This happens because, without geometric supervision, the model can recover scene structure (e.g., which objects are closer) but not absolute scale.

Importantly, such scale errors are not local: the network does not typically stretch some parts of the scene while shrinking others. Instead, the entire scene is scaled by a single factor \( s \), yielding predictions \( \hat {d}_i = s \cdot d_i \) for all pixels \( i \). For instance, if a model interprets a real cat as a small nearby toy, it will likely interpret a real car as a small toy car—misestimating scale consistently across objects and spatial regions.

This uniformity arises because the only available supervision—the ground truth depth—reveals the correct scale globally. Thus, if the network makes a pure scaling mistake, it will affect all depths equally, and a single correction factor suffices to align prediction with ground truth: \[ \frac {\hat {d}_i}{\hat {d}_j} = \frac {s \cdot d_i}{s \cdot d_j} = \frac {d_i}{d_j}. \] The scale-invariant loss captures this by canceling out any constant log-depth offset across the image. It ensures the network is trained to preserve relative structure, while ignoring inevitable global scale ambiguity in monocular input.

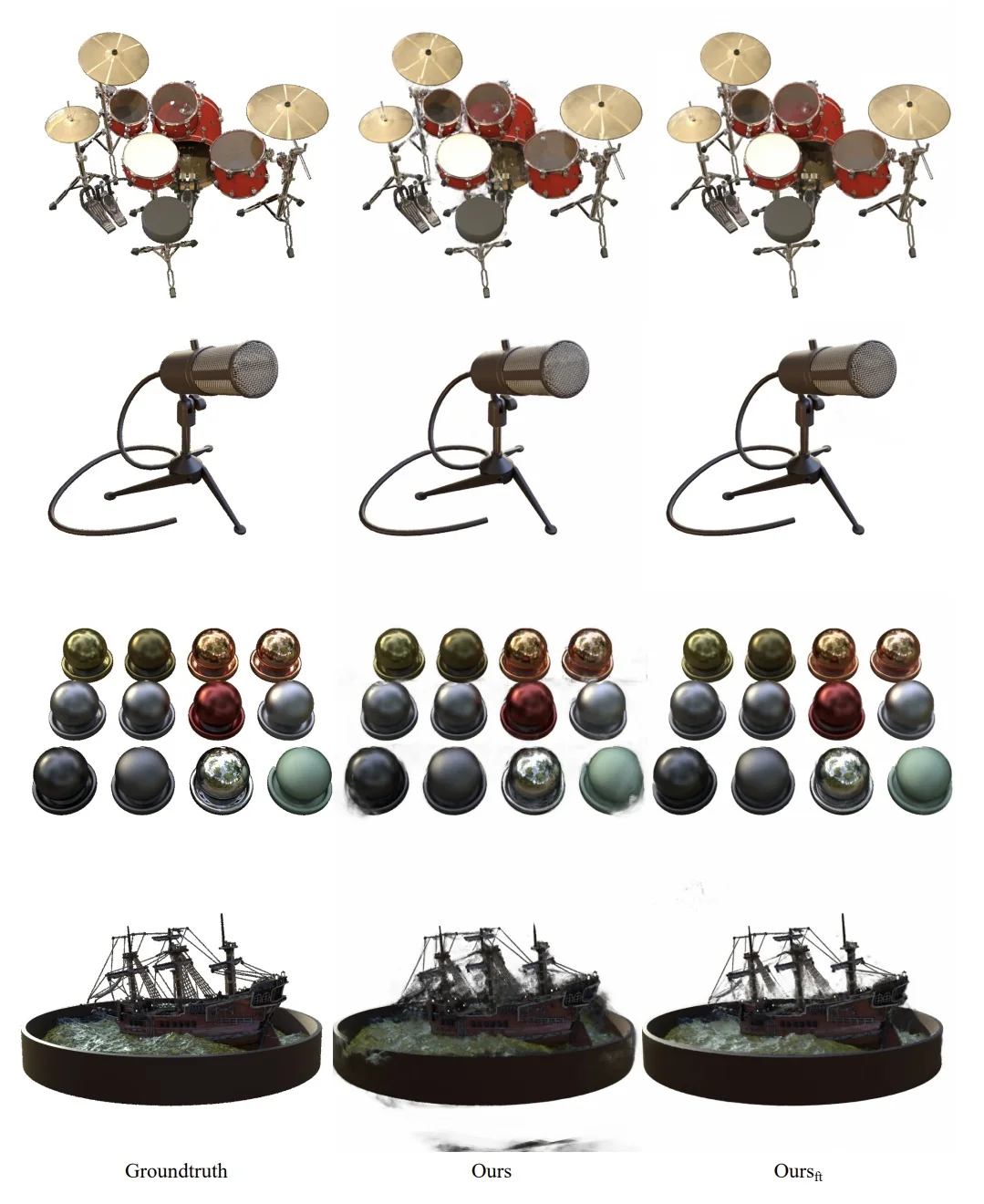

Scale and Shift-Invariant Losses in MiDaS and DPT Training monocular depth models on diverse datasets poses a core challenge: different datasets often encode depth with varying units, unknown camera baselines, or arbitrary scale and shift. For example, structure-from-motion yields depths up to scale, while stereo systems may produce disparities with dataset-specific offsets. Comparing predictions directly to such ground truth is ill-defined.

To address this, MiDaS [511] and DPT [510] adopt a scale and shift invariant objective that aligns predictions to ground truth before measuring error. Specifically, they operate in inverse depth (disparity) space—numerically stable and compatible with diverse sources—and fit an affine transformation to the predicted disparity \( \hat {d} \in \mathbb {R}^N \) to match the ground truth \( d \in \mathbb {R}^N \). The aligned prediction is given by: \[ \hat {d}_{\mbox{aligned}} = a \hat {d} + b, \] where \( a \in \mathbb {R} \) (scale) and \( b \in \mathbb {R} \) (shift) are computed via closed-form least-squares.

Robust Trimmed MAE and Multi-Scale Gradient Losses Once aligned, the model minimizes two complementary objectives that address distinct challenges in real-world training data:

1. Trimmed Mean Absolute Error (tMAE). Rather than computing loss over all pixels, MiDaS and DPT discard the highest residuals—typically the top 20%—and compute the L1 error over the remaining high-confidence set \( \mathcal {I} \subset \{1, \dots , N\} \): \[ \mathcal {L}_{\mbox{tMAE}}(d, \hat {d}) = \frac {1}{|\mathcal {I}|} \sum _{i \in \mathcal {I}} \left | a \hat {d}_i + b - d_i \right |. \]

This trimmed loss improves robustness in two ways. First, the use of L1 error prevents extreme residuals from dominating the loss—unlike L2, which excessively penalizes large errors. Second, trimming ensures that corrupted or misaligned pixels (e.g., due to missing depth, motion blur, or sensor artifacts) do not influence training. In effect, it converts noisy datasets into reliable training signals by emphasizing clean, consistent regions first, and gradually incorporating harder cases as the model improves.

2. Multi-Scale Gradient Matching. While the trimmed MAE loss ensures accuracy on reliable pixels, it does not capture how depth changes across space—that is, it ignores the local geometry of surfaces. To remedy this, MiDaS and DPT incorporate a multi-scale gradient loss that encourages the predicted depth map to exhibit the same structural transitions and surface boundaries as the ground truth.

The depth gradient at a pixel refers to the rate of change in depth with respect to its horizontal and vertical neighbors. In flat, smooth regions (e.g., walls, floors), depth changes slowly and the gradient is small. At object boundaries or depth discontinuities (e.g., the edge of a chair or the silhouette of a person), depth shifts abruptly and the gradient is large. Thus, gradients serve as a proxy for geometry: they capture where and how the scene bends, steps, or ends.

Mathematically, the spatial gradient \( \nabla d_i \) is computed using finite differences in the \(x\) and \(y\) directions—typically as: \[ \nabla d_i = \left ( d_{i+\hat {x}} - d_i,\;\; d_{i+\hat {y}} - d_i \right ), \] where \( \hat {x} \) and \( \hat {y} \) denote offsets to right and bottom neighbors. This simple local operation reveals the slope of the depth surface around each pixel.

The multi-scale gradient loss compares these gradients between prediction and ground truth at various spatial resolutions: \[ \mathcal {L}_{\mbox{grad}} = \sum _{s} \frac {1}{N_s} \sum _{i=1}^{N_s} \left \| \nabla \hat {d}_i^{(s)} - \nabla d_i^{(s)} \right \|_1. \] The use of an L1 norm ensures robustness to local mismatches. The summation over scales \( s \) (e.g., full, half, quarter resolution) allows the model to reason about both coarse structure (e.g., floor-to-wall transitions) and fine details (e.g., edges of thin objects).

Why it works: Traditional pixel-wise losses tend to average out sharp transitions, producing overly smooth or blurry depth maps. Gradient supervision counteracts this by explicitly penalizing structural mismatches. It teaches the model not only to match depth values, but to replicate the contours and discontinuities that define the geometry of the scene.

In effect, this loss forces the network to answer: Where do depth changes occur? How sharply? Do they match real-world object boundaries? The result is depth predictions with sharper edges, more accurate occlusions, and higher geometric fidelity—particularly important in zero-shot transfer settings where structure is more reliable than absolute scale.

Summary While pixel-wise \(\ell _2\) loss offers a straightforward entry point to monocular depth estimation, it fails to resolve the ill-posed nature of global scale recovery. Modern approaches instead adopt scale- and shift-invariant losses in log-depth or inverse-depth space, often augmented with gradient structure terms. These advances—combined with diverse training data and stronger architectures—have led to state-of-the-art results in monocular depth estimation across benchmarks such as KITTI, NYUv2, and ETH3D.

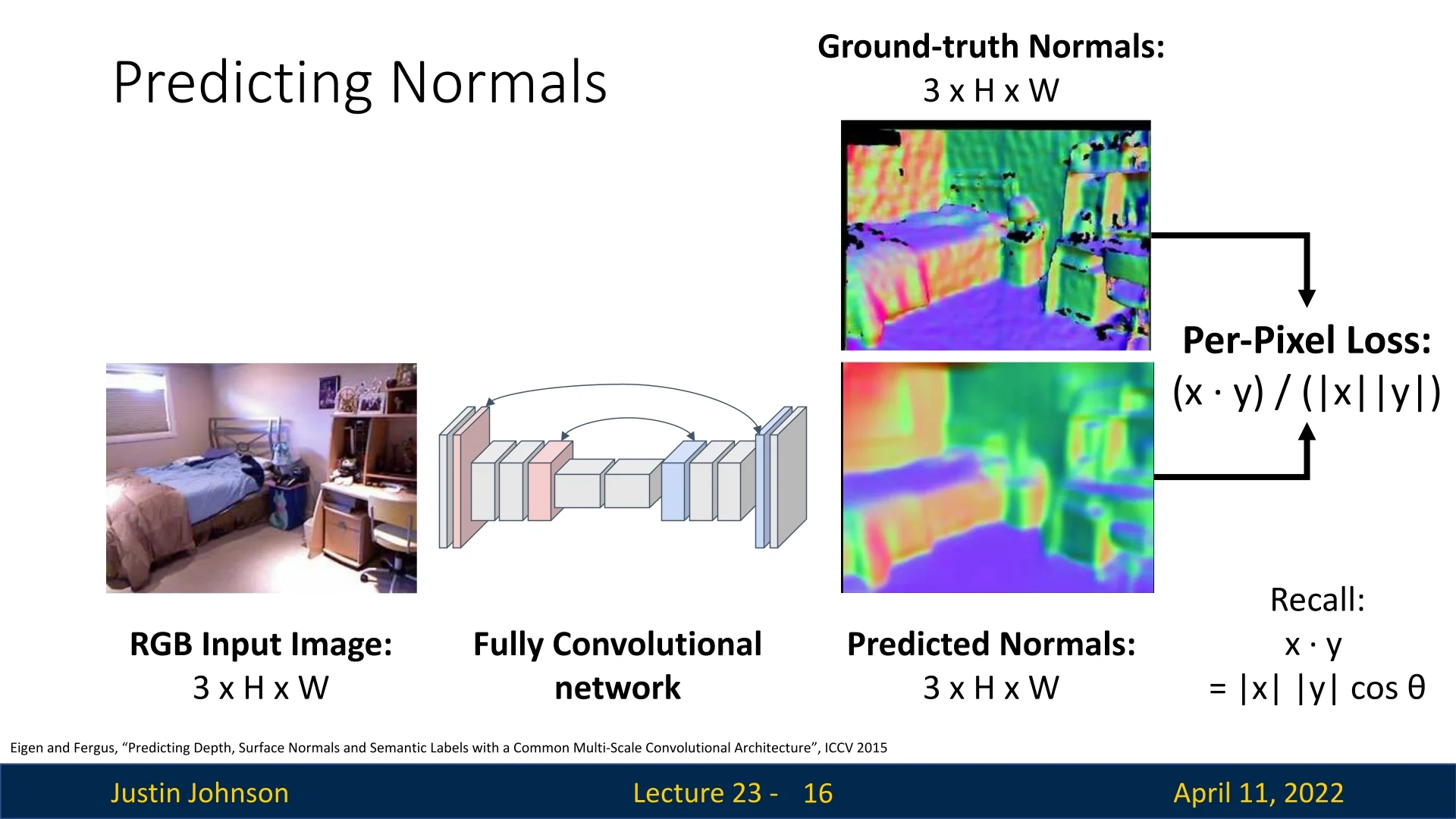

23.3 Surface Normals as a 3D Representation

In addition to depth maps, another powerful per-pixel 3D representation is that of surface normals. For each pixel in the input image, the goal is to estimate a 3D unit vector that represents the orientation of the local surface at that point in the scene. Surface normals are tightly linked to the underlying geometry of the object and provide a complementary view to depth.

Unlike depth, which encodes the distance between the camera and scene points, surface normals capture orientation, offering critical cues for understanding shape, curvature, and object boundaries.

Visualizing Normals Since each surface normal is a unit vector in \(\mathbb {R}^3\), they can be visualized as RGB images by mapping the \(x\), \(y\), and \(z\) components of each normal vector to the red, green, and blue color channels, respectively. This visualization provides intuitive insight into the orientation of different surfaces.

Learning Surface Normals Similar to depth prediction, surface normal estimation can be framed as a dense regression task using a fully convolutional network. The network predicts a unit vector \( \hat {\mathbf {n}}_i \in \mathbb {R}^3 \) for each pixel \( i \), and the objective is to align it with the corresponding ground truth normal \( \mathbf {n}_i \in \mathbb {R}^3 \). Since the predicted and ground truth vectors should have the same direction regardless of scale, a natural loss function is the cosine similarity loss:

\[ \mathcal {L}_{\mbox{normal}} = \frac {1}{N} \sum _{i=1}^{N} \left ( 1 - \frac { \hat {\mathbf {n}}_i \cdot \mathbf {n}_i }{ \| \hat {\mathbf {n}}_i \|_2 \cdot \| \mathbf {n}_i \|_2 } \right ), \]

where \( \cdot \) denotes the dot product and \( \| \cdot \|_2 \) is the Euclidean norm. Note that since ground truth normals are unit vectors, predicted vectors are often explicitly normalized before loss computation.

Multi-Task Learning In practice, tasks like dense segmentation and surface normal prediction are often trained jointly in a multi-task setup, sharing the same encoder but having separate decoders. This setup encourages the model to learn a richer and more consistent geometric understanding of the scene.

Limitations While both depth and surface normals provide dense and informative representations of the visible geometry in an image, they share a critical limitation: they are inherently restricted to visible surfaces. Occluded regions, hidden backsides, and self-occlusions are not represented, leading to incomplete scene understanding. To address this, more global 3D representations such as voxels, point clouds, or meshes are necessary, as they model complete volumetric structure beyond the image plane.

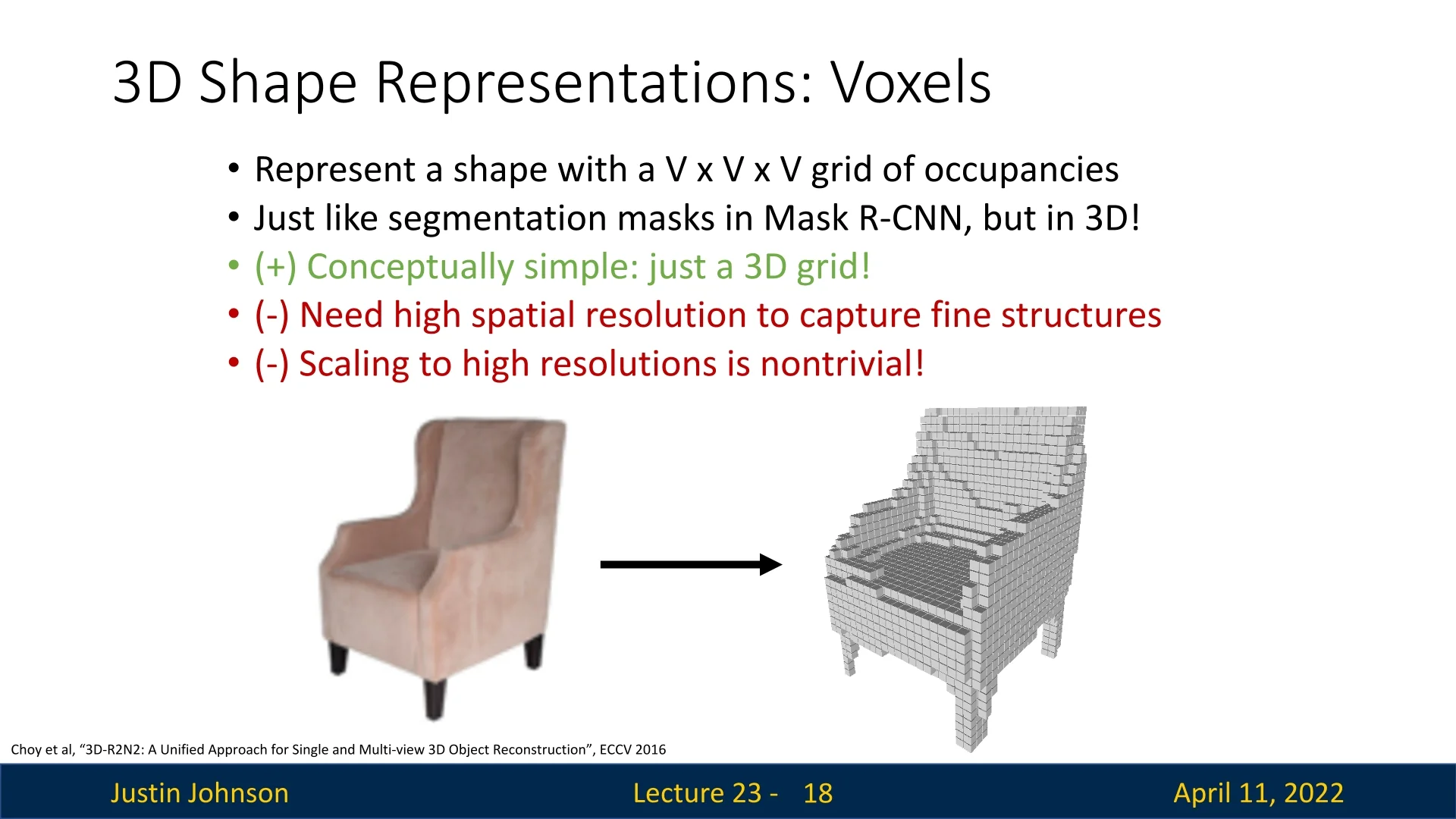

23.4 Voxel Grids

To model 3D geometry beyond visible surfaces, one of the most intuitive volumetric representations is the voxel grid. A voxel grid discretizes 3D space into a cubic lattice of resolution \( V \times V \times V \), where each voxel encodes occupancy information—typically as a binary value: \(1\) if the voxel is occupied by an object, and \(0\) otherwise. This can be viewed as the 3D analog of a 2D binary segmentation mask, but extended to volumetric space.

Voxel grids offer a conceptually simple and regular structure, making them attractive for early 3D learning pipelines. The representation is reminiscent of how objects are composed in voxel-based environments such as Minecraft, where entire scenes are built from discrete blocks.

Advantages The voxel grid format enables straightforward adaptation of classical CNN-based architectures to 3D data by replacing 2D convolutions with 3D convolutions. Since the voxel grid is regular and aligned to a grid structure, operations like pooling, upsampling, and convolution generalize naturally from 2D to 3D.

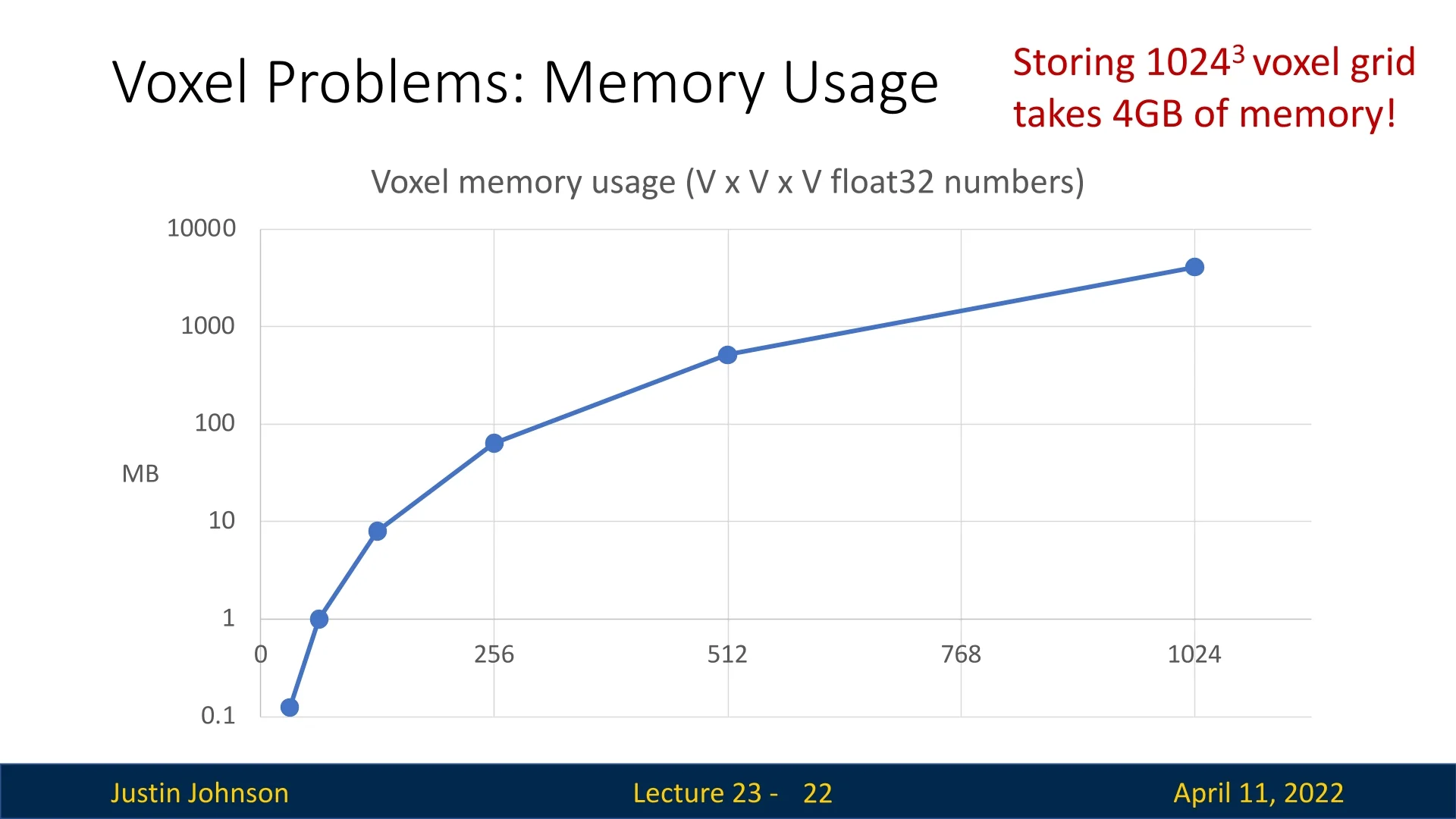

Limitations A critical downside of voxel-based representations is their poor scalability with resolution. The memory and computational cost of processing a voxel grid scales cubically with resolution: storing a grid of resolution \( V \) requires \( O(V^3) \) space. This rapidly becomes intractable for high-resolution scenes or objects, and fine details are lost at coarse voxel resolutions.

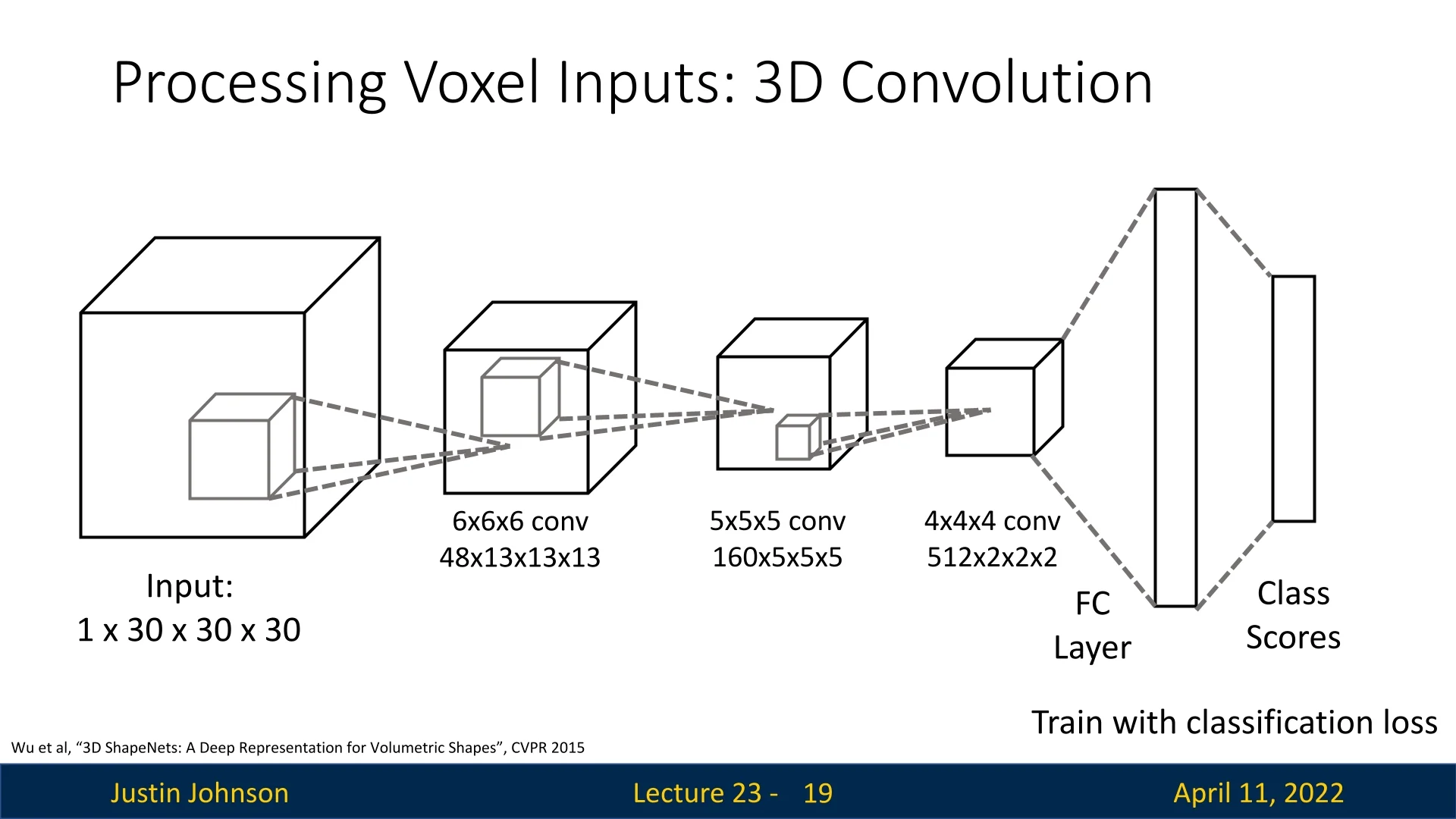

3D Convolutional Processing Similar to 2D convolution, a 3D convolution applies a local filter over spatial neighborhoods in the voxel grid. The kernel is a 3D volume of shape \( k \times k \times k \) (typically \(k=3\) or \(5\)), and it slides across the grid to compute local features:

\[ y(i, j, k) = \sum _{u,v,w} x(i+u, j+v, k+w) \cdot w(u, v, w), \]

where \( x \) is the input voxel grid or feature map, \( w \) is the learned 3D kernel, and \( y \) is the resulting activation map. These operations can be stacked in deep 3D convolutional networks to perform classification, segmentation, or shape completion.

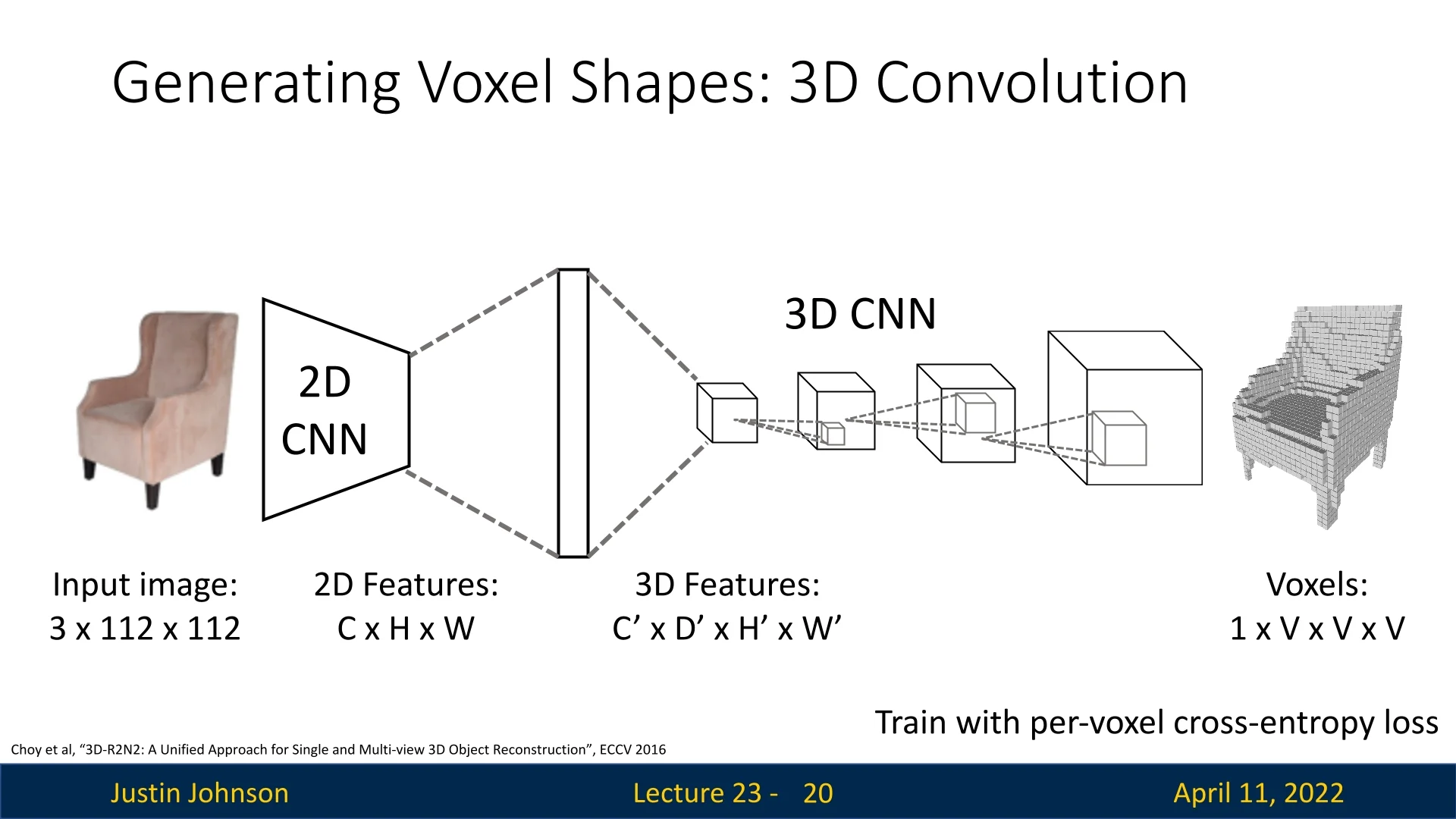

Application Example: Image-to-Voxel Prediction A representative application of voxel-based shape representation is 3D reconstruction from a single RGB image. In this example, an image of an armchair is processed by a 2D convolutional neural network to extract high-level visual features. These features are then projected into a latent 3D space and refined through a sequence of 3D convolutional layers, ultimately producing a predicted voxel occupancy grid.

The pipeline begins with a \(3 \times 112 \times 112\) input image, which is passed through a 2D CNN backbone to generate a compressed feature representation. This feature tensor is reshaped or lifted into a 3D voxel grid of shape \(1 \times V \times V \times V\) (e.g., \(32^3\)). The lifted volume is then processed by 3D convolutional filters that reason about the spatial structure of the object in three dimensions.

The final output is a binary or probabilistic voxel grid indicating which regions of 3D space are likely to be occupied by the object. In our example, the network successfully reconstructs the volumetric shape of an armchair directly from a single view.

This architecture exemplifies how convolutional models can bridge 2D visual perception and 3D spatial reasoning. The voxel grid serves as an interpretable intermediate representation, enabling volumetric reasoning for tasks such as shape completion, reconstruction, etc.

As can be seen in figure 23.8, due to the cubic growth of memory and compute with resolution, voxel-based methods are constrained in practice, motivating alternative representations such as point clouds, triangle meshes, and neural implicit fields for higher-fidelity modeling. One thing we can do though, is try to scale voxels based on Oct-Trees.

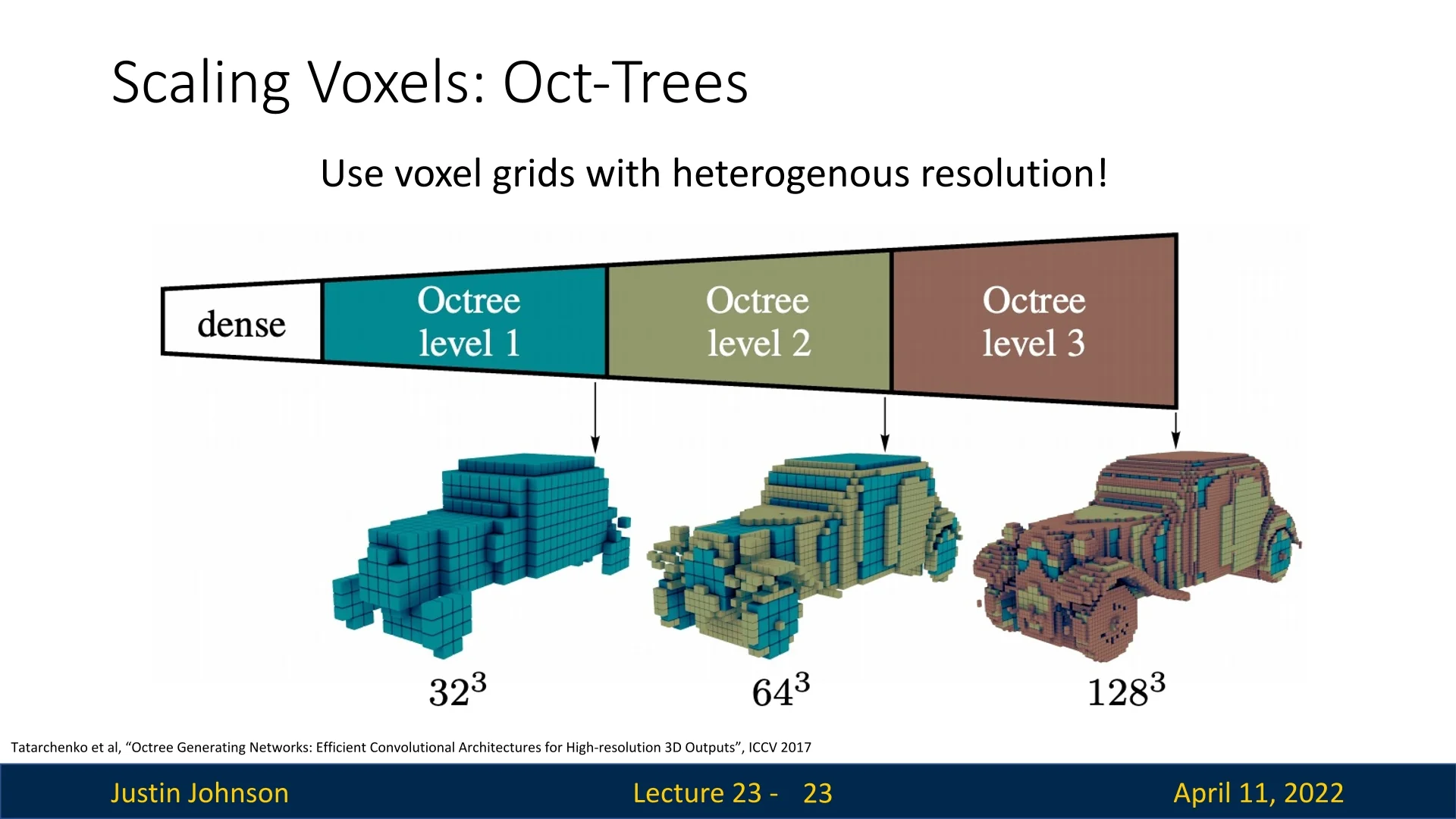

23.4.1 Scaling Voxel Grids with Octrees

Standard voxel grids suffer from a key limitation: memory and computation grow cubically with resolution. For instance, going from a \(32^3\) to \(128^3\) grid multiplies storage cost by a factor of \(4^3 = 64\). At high resolutions, this becomes intractable—even though most of the grid is typically empty or homogeneous. This makes dense voxelization wasteful and limits its ability to capture fine geometric detail.

To overcome this inefficiency, Tatarchenko et al. introduced the Octree Generating Network (OGN) [609], which replaces dense grids with a sparse hierarchical structure called an octree.

Octrees: Intuition and Structure An octree is a tree-based representation that adaptively subdivides 3D space. Starting from a single cube that covers the full scene (the root), each cube is recursively split into eight subcubes (octants)—but only when that region contains surface detail. Empty or homogeneous regions remain unrefined.

- Uniform regions (e.g., open air or flat walls) are stored as large, coarse octree nodes.

- Detailed regions (e.g., object boundaries or thin parts) are recursively subdivided to finer scales.

This adaptive spatial resolution means memory is focused where it matters: on the surface.

From Dense to Adaptive To illustrate the impact, consider representing a car at different voxel resolutions:

- A dense \(128^3\) grid would allocate over two million voxels, even for empty space.

- In contrast, an octree might use only thousands of voxels—concentrated near the car’s surface.

This reduces overall memory complexity from \(O(n^3)\) to approximately \(O(n^2)\), since the object’s surface is a 2D manifold embedded in 3D space.

Octree Generating Networks (OGNs) OGN is a convolutional architecture that generates high-resolution 3D shapes in octree format. It starts with a coarse prediction of shape (e.g., \(8^3\) or \(16^3\)) and recursively refines it. The model learns to predict:

- which voxels should be subdivided (occupancy probabilities),

- and what features to pass to each child octant (learned latent codes).

At each refinement level, the network only expands voxels flagged as informative. This enables high-fidelity 3D shape generation—without wasting memory on empty regions.

Surface-Driven Efficiency The advantage of octrees becomes clearest at high resolutions. Rather than processing millions of voxels uniformly, OGNs focus computation where object geometry is complex. For example, flat car doors are left coarse, while wheels or window edges are subdivided further.

Why and How Octrees Work Octrees address storage inefficiency by adaptively refining the voxel grid only where necessary, enabling surface-focused representations with far less memory.

How it works: The octree starts with a coarse resolution (e.g., \(32^3\)) and maintains a tree where each node represents a voxel. Each node can be classified as:

- empty: the voxel contains no surface and is not refined further;

- filled: the voxel lies entirely inside the object and needs no further subdivision;

- mixed: the voxel intersects a surface and is therefore recursively subdivided into 8 children.

The key challenge is determining which voxels to refine.

Predicting Subdivision with Neural Networks At each level of refinement, the octree maintains a sparse set of active leaf voxels. For each such voxel, the network predicts:

- 1.

- A feature vector for the current voxel (using sparse 3D convolutions on the octree structure).

- 2.

- An occupancy classification score for the voxel itself.

- 3.

- A set of 8 binary flags, one for each potential child voxel. indicating whether that subregion should be refined.

The voxel is only subdivided if at least one child is predicted as filled or mixed—that is, likely to be part of the object’s interior or intersect the surface. These predictions are made using a split prediction head that branches off the decoder.

Training with Supervised Supervision OGNs are trained end-to-end using ground truth voxel occupancy grids, from datasets like ShapeNet. The training process proceeds in a coarse-to-fine manner:

- At level \(l\) (e.g., \(32^3\)): The network processes the current octree level and predicts occupancy and subdivision flags for each voxel.

- Ground truth comparison: The predicted occupancy labels and subdivision decisions are supervised using binary cross-entropy losses against a precomputed ground truth octree. These labels are derived by voxelizing the 3D CAD mesh and marking voxels as filled, empty, or mixed.

- Subsequent levels: Only voxels marked for refinement are subdivided. Their children become the active set for the next finer resolution level (e.g., \(64^3\), then \(128^3\), etc.).

This recursive supervision continues until the desired maximum resolution is reached. The result is a hierarchical, sparsely populated voxel grid that concentrates resolution along object surfaces, drastically reducing memory and computation.

- Focuses computation: By refining only ambiguous voxels, the model avoids spending resources on empty space or flat interiors.

- Learns detail adaptively: The network learns where detail is needed from data, rather than relying on hand-crafted refinement rules.

- Enables higher resolutions: Because only a subset of voxels are represented at each level, OGNs can generate outputs at resolutions like \(256^3\) or \(512^3\) with the memory footprint of a much smaller dense grid.

This learned coarse-to-fine generation strategy allows octree-based models to efficiently capture complex geometry while remaining scalable, making them highly effective for high-resolution 3D shape prediction tasks.

Limitations and Motivation for Point-Based Methods Despite their efficiency, octrees still discretize space into axis-aligned cubes, which limits their ability to model very fine surface curvature or sharp boundaries without deep subdivisions. Moreover, generating and traversing octree hierarchies can introduce implementation complexity and latency in practice.

These limitations motivate an alternative family of 3D representations: point clouds. Unlike voxel grids or octrees, point clouds represent surfaces directly via sampled points in \(\mathbb {R}^3\), bypassing the need to discretize space altogether. Although voxel representation is pretty common in practice, and point-based methods do not benefit from the grid structure useful in convolutional networks, they are intriguing as they offer greater flexibility and memory efficiency, especially for capturing fine-grained surface geometry.

In the following part, we explore point cloud representations and the neural architectures designed to process them effectively.

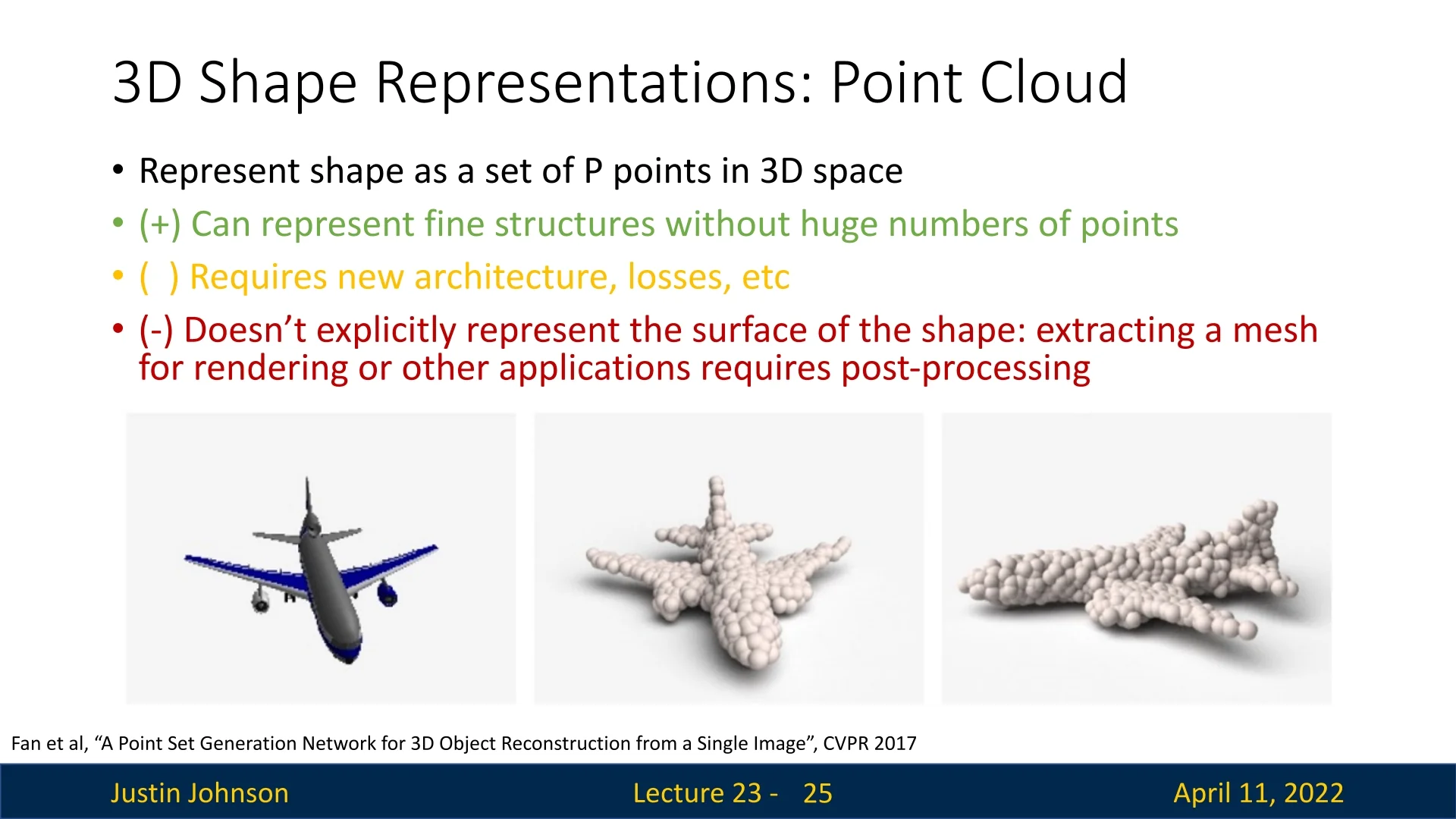

23.5 Point Clouds

A point cloud is a flexible, sparse, and surface-centric representation of 3D geometry. It models an object as a set of \( P \) points in \( \mathbb {R}^3 \), each corresponding to a sampled position on the visible surface: \[ \mathcal {P} = \{ \mathbf {p}_i \in \mathbb {R}^3 \mid i = 1, \ldots , P \} \]

Unlike voxel grids, which discretize the 3D space uniformly and incur cubic memory costs, point clouds only represent surface points, yielding a compact and efficient encoding. This representation aligns naturally with real-world sensor data, such as LiDAR in autonomous vehicles.

Advantages Point clouds allow for high-resolution geometric modeling without the cubic scaling of voxel-based methods. They efficiently capture fine details such as airplane wings or chair slats using a relatively small number of points (as shown in figure 23.10), while coarser regions like planar surfaces can be represented sparsely.

Limitations Point clouds do not encode surface connectivity or topology. This limits their utility for downstream applications such as mesh rendering or physics simulation, which rely on explicit surface structure. Additionally, point clouds are unordered and irregularly sampled, requiring specialized neural architectures for effective processing.

Rendering Since mathematical points are infinitesimal, visualizations inflate each point into a finite-radius sphere. This creates the illusion of a continuous surface but does not resolve the lack of connectivity. To use point clouds for graphics or simulation, surface reconstruction via meshing algorithms is often necessary.

Applications Point clouds are a core representation in 3D perception and are widely used in robotics, AR/VR, and autonomous driving. In particular, LiDAR sensors deployed on self-driving vehicles emit laser pulses to scan the environment and return a dense set of 3D points corresponding to surfaces in the scene. This raw point cloud data forms the foundation for several high-level tasks:

- Obstacle detection and tracking: Dynamic objects such as vehicles, pedestrians, and cyclists are localized and tracked in 3D space, enabling collision avoidance and motion planning.

- Semantic scene understanding: Each point in the cloud can be semantically labeled as road, building, vegetation, etc., supporting downstream reasoning about the environment.

- Mapping and localization: Aggregated LiDAR scans are used to construct high-definition (HD) maps for accurate self-localization and route planning. These maps include fine-grained structures such as lane boundaries, curbs, and traffic signs.

- Multi-sensor fusion: Point clouds are often fused with camera and radar inputs to improve robustness under challenging conditions, such as poor lighting or weather, where single modalities may fail.

By capturing precise geometric structure independent of appearance, point clouds enable spatial reasoning and metric-scale perception, making them indispensable for autonomous systems operating in complex, dynamic environments.

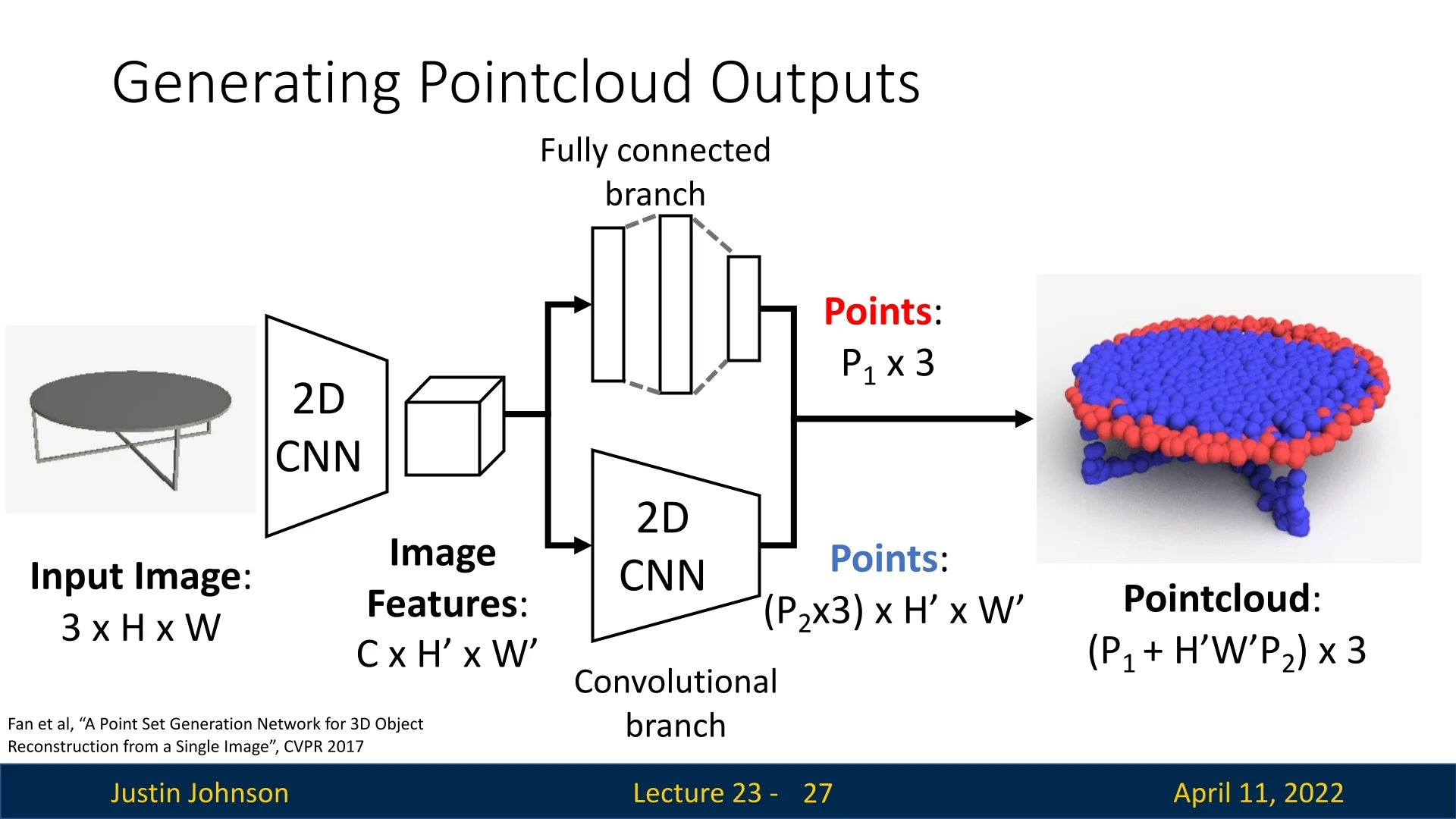

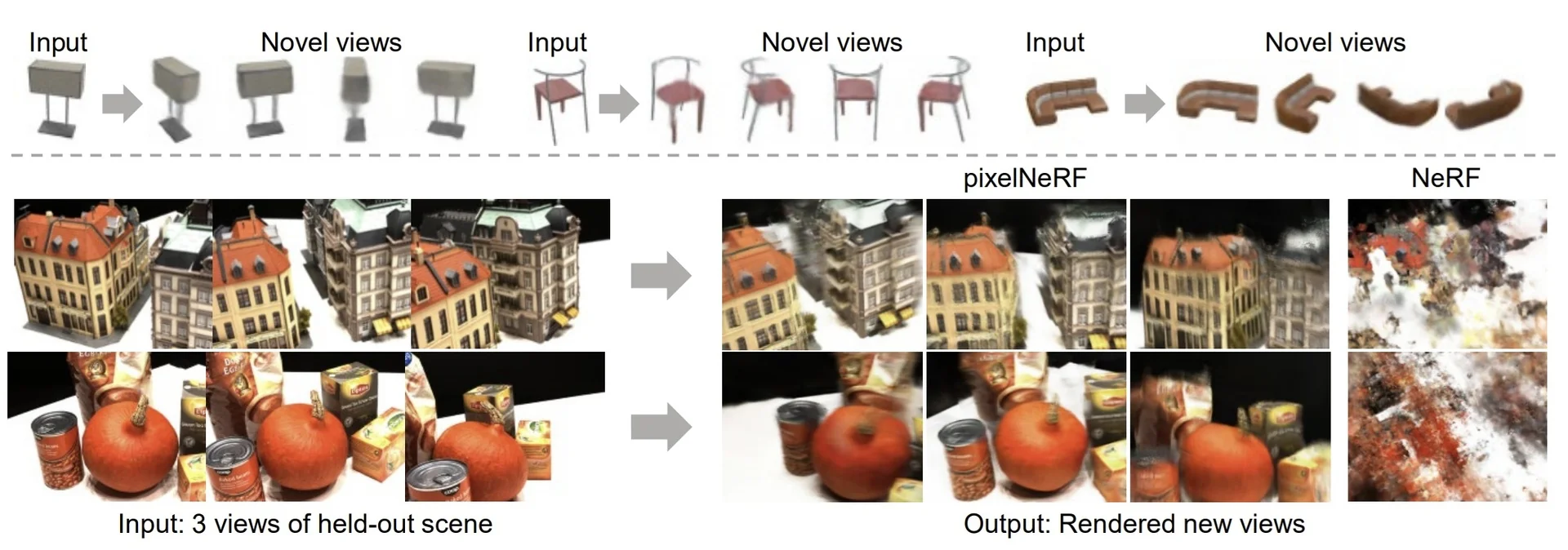

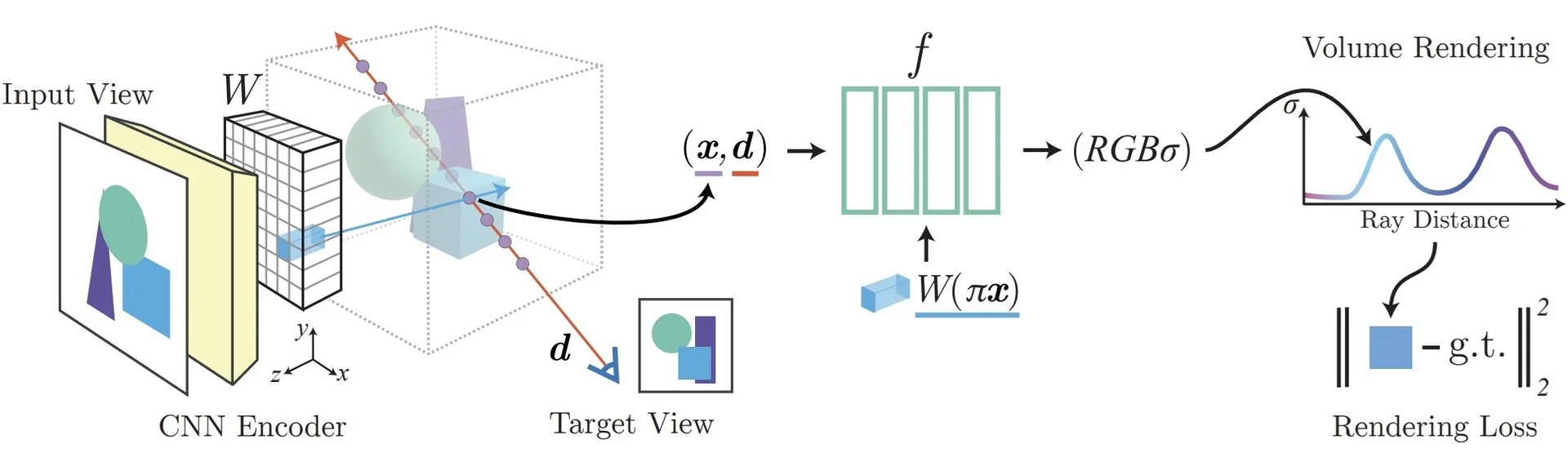

23.5.1 Point Cloud Generation from a Single Image

Fan et al. [152] introduce a landmark framework for reconstructing 3D shapes as point sets directly from a single RGB image. Unlike voxel grids or multi-view representations, point clouds are efficient, resolution-independent, and naturally suited to surface-level geometry. The model predicts an unordered set of 3D points \[ \hat {S} = \{\,\hat {y}_i\,\}_{i=1}^{P_1 + H'W'P_2} \subset \mathbb {R}^3, \] which approximates the visible object surface.

Architecture Overview The model follows an encoder–decoder structure with a dual-branch output head designed to capture both global object structure and fine surface detail.

- The encoder is a convolutional neural network that maps the input image \( I \in \mathbb {R}^{3 \times H \times W} \) to a latent feature tensor \( F \in \mathbb {R}^{C \times H' \times W'} \). This feature map encodes rich spatial information about the input’s underlying 3D geometry.

-

The decoder splits into two complementary branches:

-

Fully-Connected (Global) Branch: The feature map \(F\) is flattened and passed through a multi-layer perceptron (MLP) to produce a fixed set of \(P_1\) 3D points: \[ \hat {S}^{\mathrm {g}} = \{\,\hat {y}_i^{\mathrm {g}}\,\}_{i=1}^{P_1} \subset \mathbb {R}^3. \] The output dimensionality is predetermined—e.g., a final layer with \(3 \cdot P_1\) units reshaped into a \(P_1 \times 3\) matrix. This branch captures the global structure, pose, and coarse silhouette of the object. The hyperparameter \(P_1\) is typically chosen to balance expressiveness and efficiency, and remains fixed during training and inference.

- Convolutional (Local) Branch: Rather than collapsing spatial dimensions, this branch operates directly over the \(H' \times W'\) grid of the encoded feature map. At each spatial location \((i, j)\), a shared MLP (implemented as \(1 \times 1\) convolution) predicts \(P_2\) 3D points: \[ \hat {S}^{\mathrm {l}} = \{\,\hat {y}_{i,j,k}^{\mathrm {l}}\,\}_{i=1}^{H'}{}_{j=1}^{W'}{}_{k=1}^{P_2} \subset \mathbb {R}^3. \] Each point is generated relative to a canonical 2D grid anchor, allowing the network to model high-frequency surface detail. The weight-sharing mechanism enforces translation-equivariant behavior across the image, which is particularly effective for capturing fine geometry such as edges, contours, and thin structures. Because it preserves spatial layout, this branch provides dense, localized surface coverage.

-

The final output is the union of both branches: \[ \hat {S} = \hat {S}^{\mathrm {g}} \cup \hat {S}^{\mathrm {l}}, \quad \mbox{with} \quad |\hat {S}| = P_1 + H'W'P_2. \]

This architecture enables the model to combine a globally consistent shape prior (via the FC branch) with spatially grounded local refinement (via the convolutional branch), yielding geometrically faithful point cloud reconstructions with efficient capacity allocation.

Architectural Motivation This dual-path architecture reflects a coarse-to-fine design philosophy:

- The global branch supplies a stable structural prior, capturing the object’s pose, orientation, and rough geometry.

- The local branch attends to spatially localized visual cues, enriching the surface detail with high-frequency geometric structure—particularly beneficial for recovering thin parts and sharp edges.

Together, they allow the network to generate accurate and detailed 3D reconstructions while keeping output size and model complexity manageable.

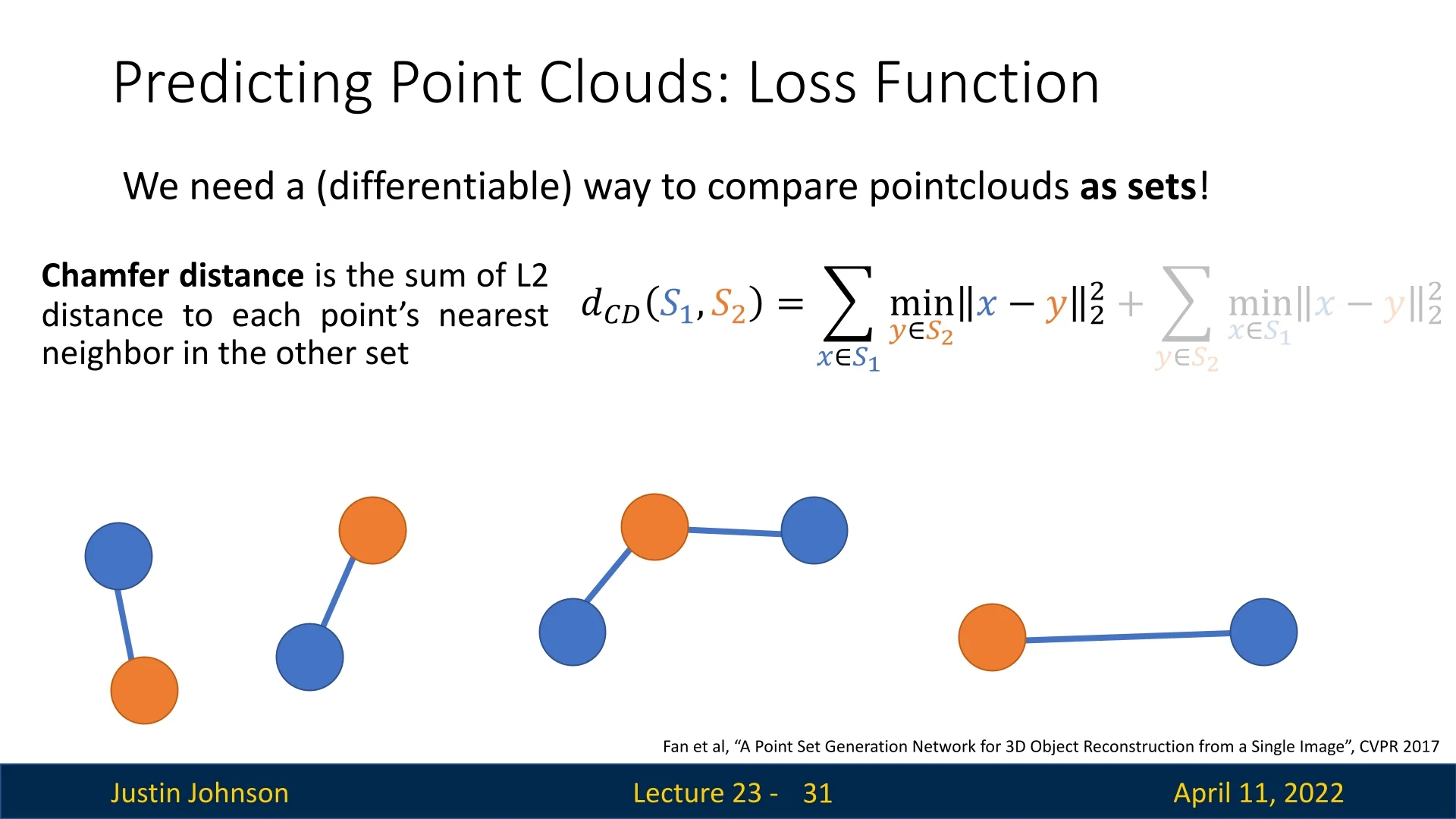

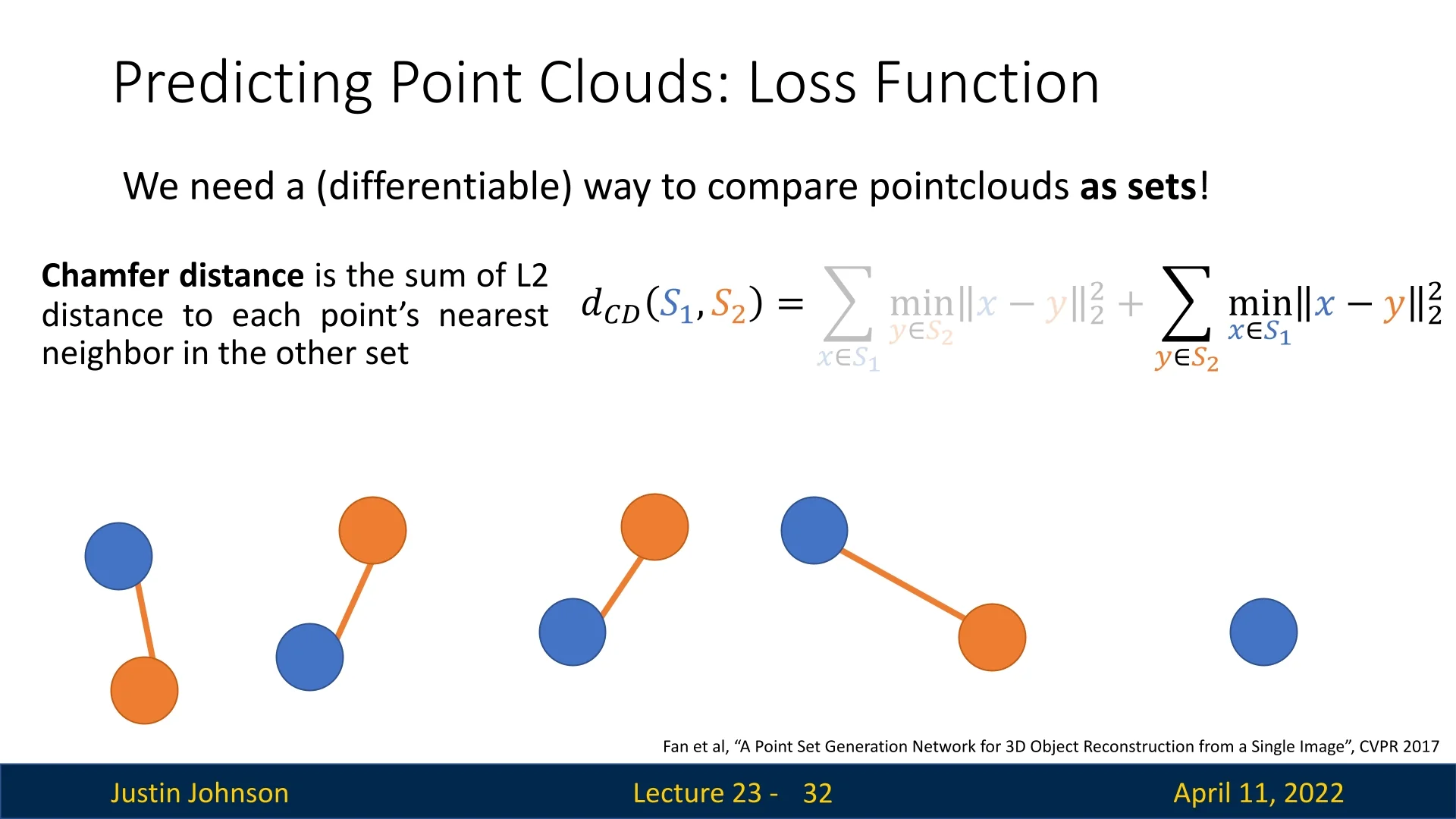

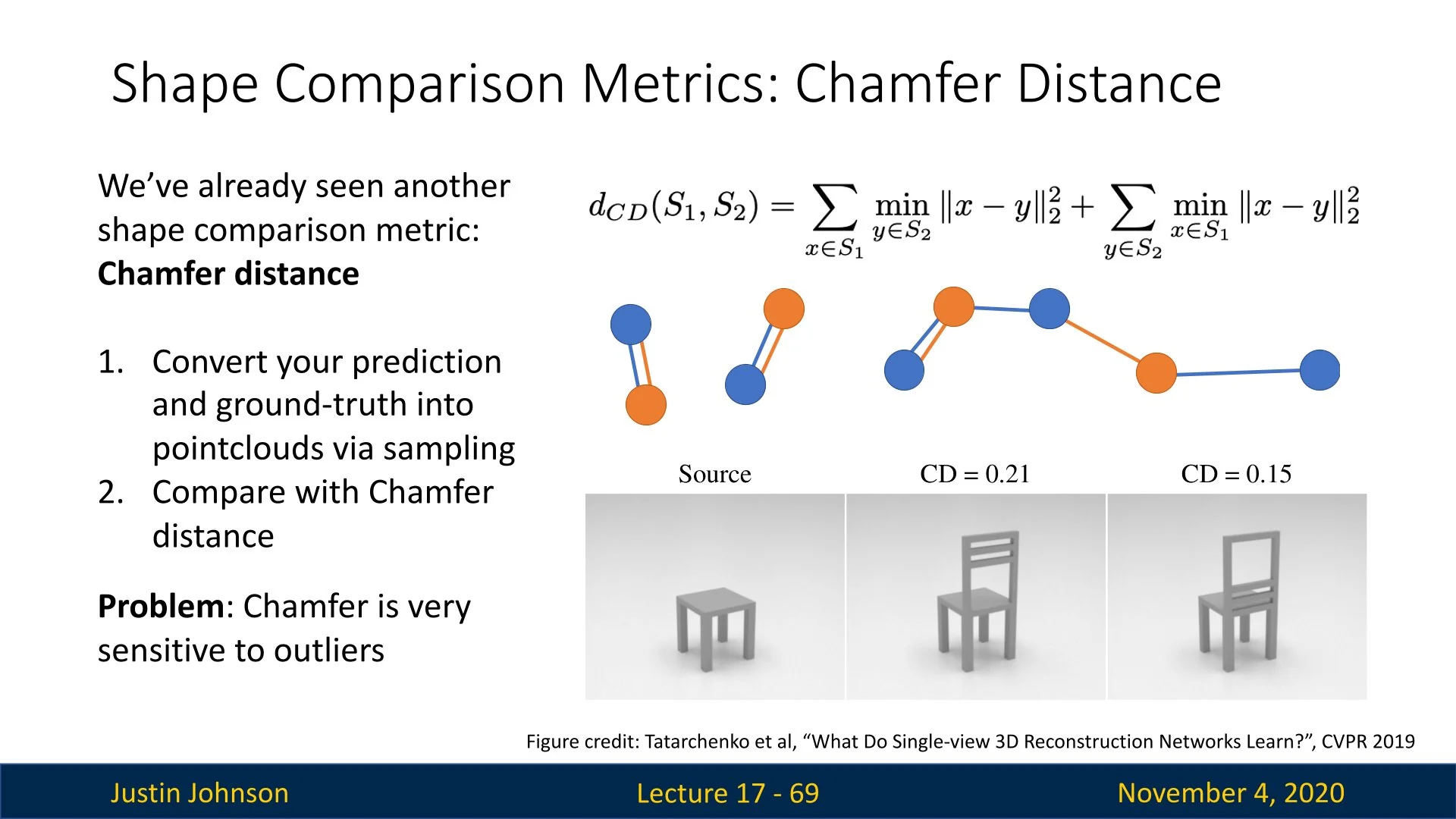

Loss Function: Chamfer Distance When predicting 3D point clouds, we aim to generate a set of points that matches a ground-truth shape surface. Crucially, both the predicted and target sets are unordered—permuting point indices does not change the represented shape. This calls for a set-based loss function that is invariant to point ordering and flexible to varying cardinality.

Fan et al. address this with the Chamfer Distance (CD), a symmetric, differentiable measure of dissimilarity between two point sets:

- \( S_1 \subset \mathbb {R}^3 \): predicted point cloud (previously \( \hat {S} \))

- \( S_2 \subset \mathbb {R}^3 \): ground-truth point cloud (previously \( S \))

The Chamfer Distance is defined as: \[ d_{\mathrm {CD}}(\textcolor {blue}{S_1}, \textcolor {orange}{S_2}) = \sum _{\textcolor {blue}{x \in S_1}} \min _{\textcolor {orange}{y \in S_2}} \|x - y\|_2^2 + \sum _{\textcolor {orange}{y \in S_2}} \min _{\textcolor {blue}{x \in S_1}} \|x - y\|_2^2. \]

Each term plays a complementary role:

- The forward term ensures that every predicted point \( \textcolor {blue}{x \in S_1} \) has a close match in the target set \( \textcolor {orange}{S_2} \). This promotes accurate surface fitting and penalizes extraneous predictions.

- The backward term guarantees that every target point \( \textcolor {orange}{y \in S_2} \) is approximated by at least one predicted point \( \textcolor {blue}{x \in S_1} \). This ensures full coverage of the ground-truth surface, even when the model predicts fewer points than the reference.

The bidirectional structure is key: even if \( |S_1| \neq |S_2| \), the loss still compares them fairly by asking how well each set ”explains” the other through nearest-neighbor matching. The use of minimum distances makes the loss permutation-invariant, and its differentiability (almost everywhere) enables end-to-end gradient-based optimization. Efficient computation is facilitated via KD-trees or approximate nearest neighbor search. The only situation in which the loss will be 0 is when the two sets are the same (each point in one is exactly on a point in the other), which is what we wanted to achieve.

Intuition and Impact The Chamfer Distance aligns naturally with the set-based nature of point clouds. By evaluating how well two sets approximate each other through nearest neighbors, it handles variable point counts and spatial distributions with ease. This makes it ideal for training neural networks to generate dense 3D surfaces from sparse supervision. Fan et al.’s use of Chamfer loss, coupled with a dual-branch decoder and CNN encoder, marked the first end-to-end framework to lift 2D images into 3D point sets with high geometric fidelity—laying the groundwork for many subsequent advances in point-based and implicit shape reconstruction.

23.5.2 Learning on Point Clouds: PointNet and Variants

Unlike images or voxels, point clouds are unordered and lack an inherent grid structure. This makes standard convolutional architectures unsuitable for directly processing them. PointNet [489] introduces a neural network architecture specifically designed to handle raw point sets while respecting their permutation invariance.

Let the input be a point cloud \( \mathcal {P} = \{p_i\}_{i=1}^P \subset \mathbb {R}^3 \), represented as a tensor \( \mathbb {R}^{P \times 3} \). PointNet processes this set in a permutation-invariant fashion using the following components:

- 1.

- Shared MLP: Apply the same MLP to each point independently: \[ \mbox{MLP}(p_i) \in \mathbb {R}^D,\quad i=1,\dots ,P \] yielding a per-point feature matrix in \( \mathbb {R}^{P \times D} \). Shared weights ensure permutation invariance across the set.

- 2.

- Symmetric Aggregation: Collapse the point cloud into a global descriptor using a permutation-invariant operator (e.g., max-pooling): \[ h_{\mbox{global}} = \max _{i=1}^P \mbox{MLP}(p_i) \in \mathbb {R}^D. \] The result is independent of input order and size.

- 3.

- Prediction Head:

- Classification: Pass \( h_{\mbox{global}} \) through fully-connected layers to produce output scores in \( \mathbb {R}^{C} \).

- Segmentation: Concatenate \( h_{\mbox{global}} \) back to each per-point feature, then apply another shared MLP to predict per-point labels.

Pose Normalization via T-Net Modules To improve invariance to arbitrary spatial transformations, PointNet incorporates two optional Transformation Networks (T-Nets) that learn to align both the input point cloud and its intermediate feature representations to canonical frames.

- Input T-Net: This module predicts a spatial alignment for the raw coordinates \( \mathcal {P} \in \mathbb {R}^{P \times 3} \). It follows the PointNet architecture—shared MLPs, max-pooling, and fully connected layers—to regress a \( 3 \times 3 \) transformation matrix, which is then applied directly to the input points. This normalization step removes global rotation and translation ambiguity, ensuring that the downstream network processes consistently oriented data.

-

Feature T-Net: A second T-Net operates on the intermediate per-point feature vectors (e.g., after the first shared MLP), predicting a \( D \times D \) transformation matrix to align feature embeddings in the latent space. This matrix is applied before aggregation, improving the stability and semantic consistency of learned features across different object poses and variations.

- Regularization: To ensure that the predicted feature transformation is approximately orthogonal (i.e., preserves information), a regularization loss of the form \[ L_{\mathrm {reg}} = \left \| I - A A^\top \right \|_F^2 \] is added to the training objective, where \( A \in \mathbb {R}^{D \times D} \) is the predicted transformation matrix and \( \| \cdot \|_F \) denotes the Frobenius norm.

By learning to normalize both geometric and feature-level representations, these T-Net modules enhance the model’s robustness to pose variation and improve the reliability of downstream classification or segmentation predictions.

Hierarchical Reasoning via Iterative Refinement Beyond the basic structure, subsequent variants of PointNet can perform multi-stage feature fusion:

- After the first max-pooling yields \( h_{\mbox{global}} \in \mathbb {R}^D \), it is concatenated with each point feature to form \( \mathbb {R}^{P \times 2D} \).

- A shared MLP processes these enriched per-point vectors.

- A second max-pooling generates a refined global descriptor.

- This sequence—concat, MLP, pooling—can be repeated multiple times, allowing the network to capture hierarchical, higher-order shape attributes.

This iterative deep set reasoning retains permutation invariance while progressively enhancing the model’s expressive power.

Legacy and Evolution PointNet demonstrated that symmetry-aware, set-based architectures can rival or surpass volumetric CNNs in classification and segmentation—while using significantly less memory and supporting higher-resolution geometry. Its simple yet powerful design has led to a series of influential extensions that form the backbone of modern 3D deep learning pipelines.

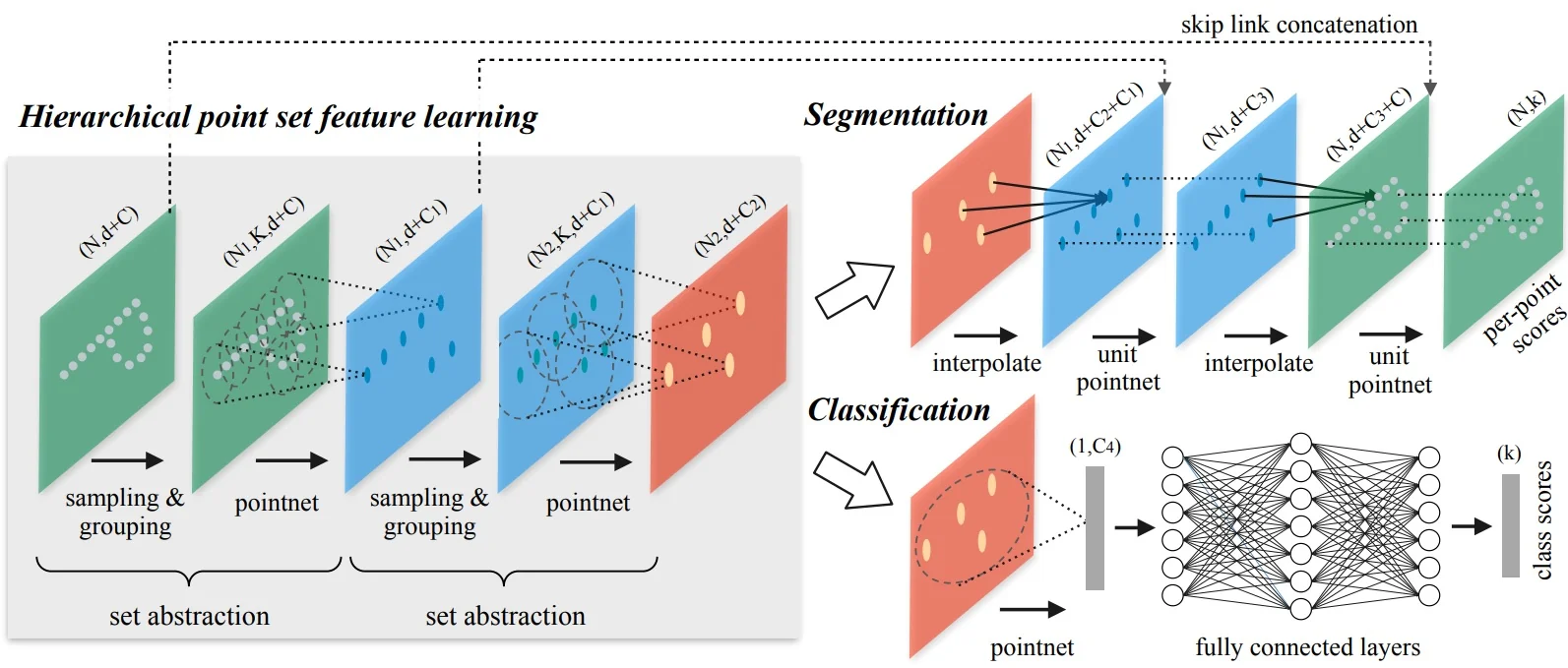

23.5.3 PointNet++: Hierarchical Feature Learning on Point Clouds

While PointNet [489] introduced a powerful set-based paradigm for point cloud processing, it suffers from a key limitation: the inability to explicitly model local geometric structures. Because PointNet aggregates all point features globally in a single pooling operation, it lacks sensitivity to fine-grained local patterns—much like trying to classify a shape without noticing its edges or corners.

PointNet++ [490] addresses this limitation by introducing a hierarchical architecture that recursively applies PointNet within spatially localized regions. This structure enables the model to learn point-wise features at progressively larger contextual scales, akin to how CNNs build up representations from local patches to full-image semantics.

The core architectural unit in PointNet++ is the Set Abstraction (SA) module, which consists of three main stages:

- 1.

- Sampling: From the full point set, a representative subset is selected as centroids of local regions. This is typically performed using Farthest Point Sampling (FPS), which ensures even spatial coverage of the point cloud by selecting points that are maximally distant from one another. This avoids clustering in high-density areas and helps capture the object’s full spatial extent.

- 2.

- Grouping: For each sampled centroid, a local neighborhood is defined. The standard method is a ball query, which includes all points within a fixed radius. This spatially bounded grouping ensures that the local features extracted are consistent and scale-aware. (Alternatively, \(k\)-nearest neighbors can be used, though ball queries preserve fixed spatial context).

- 3.

- PointNet Encoding: Within each local neighborhood, a mini-PointNet is applied—mapping the points into a local reference frame (relative to the centroid) and computing a feature vector via shared MLPs and symmetric max-pooling. This step captures local geometric properties such as curvature, edges, or flatness.

By stacking multiple SA modules, PointNet++ constructs a deep hierarchy of features—from local patches to global shape descriptors—allowing robust recognition of both coarse and detailed structure.

Density-Adaptive Grouping and Robustness A major challenge in real-world point clouds—such as those acquired via LiDAR or RGB-D sensors—is the presence of non-uniform sampling density. Nearby surfaces often result in dense clusters of points, while distant or occluded areas may be sparsely sampled. If a network uses a fixed-radius neighborhood (as in single-scale grouping), it may gather too few points in sparse regions (leading to unstable features), or be unnecessarily redundant in dense regions (wasting computation).

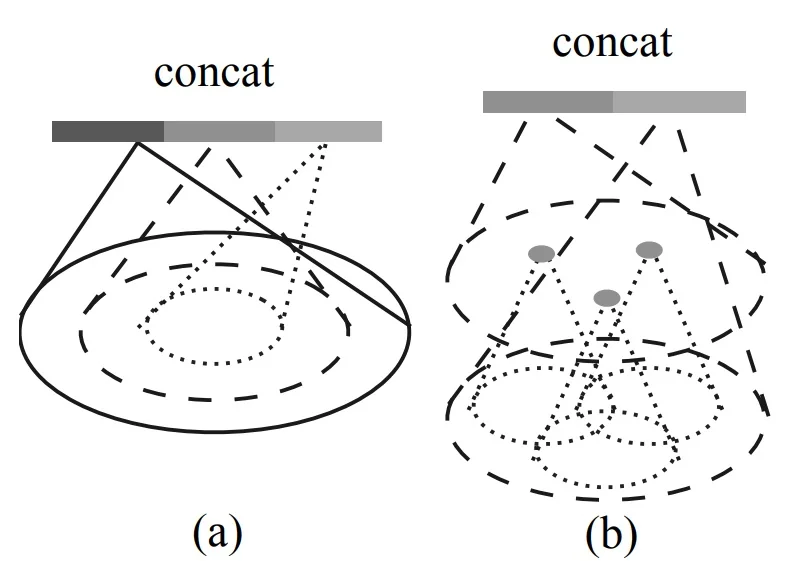

To address this, PointNet++ [490] introduces two density-adaptive grouping strategies that allow feature learning to adapt across varying sampling densities:

-

Multi-Scale Grouping (MSG): For each centroid in the set abstraction layer, MSG performs multiple ball queries of increasing radii (e.g., small, medium, large), forming concentric local neighborhoods of different scales. Each group is processed by a separate mini-PointNet, and the resulting feature vectors are concatenated into a unified multi-scale representation.

Intuition: In dense regions, small-radius neighborhoods suffice to capture fine detail; in sparse regions, larger-radius neighborhoods ensure geometric coverage. MSG makes the model robust to such density variations at the cost of increased computation due to multiple parallel branches.

-

Multi-Resolution Grouping (MRG): As a more efficient alternative, MRG leverages the hierarchical nature of PointNet++. At each level \(L_i\), the feature for a local region is computed by concatenating:

- a low-resolution feature from the previous level \(L_{i-1}\), summarizing a large, sparse context;

- a high-resolution feature from a mini-PointNet applied to the raw points in the local region at level \(L_i\).

This dual-path design allows the network to dynamically emphasize coarse or fine structure depending on local point density.

Intuition: When a region is well-sampled, detailed features from the current level dominate; when sparse, the network falls back on coarse summaries inherited from deeper layers.

Random Input Dropout: During training, PointNet++ further improves robustness by randomly dropping input points. This encourages the model to generalize across incomplete or sparsely sampled inputs—a common scenario in real-world 3D capture.

Feature Propagation for Dense Prediction For tasks like semantic segmentation—where per-point predictions are required—PointNet++ uses a feature propagation module to interpolate and upsample coarse features back to the original resolution. This is achieved via:

- Distance-weighted interpolation from nearby subsampled points.

- Skip connections from earlier levels in the hierarchy.

This ensures that each point benefits from both its raw input and the abstracted global features accumulated through the hierarchy.

Summary and Impact PointNet++ marks a major evolution in point cloud learning. By extending PointNet with hierarchical spatial reasoning, local neighborhood modeling, and density-aware design, it achieved state-of-the-art performance across classification, segmentation, and 3D object detection benchmarks at its time of publication. The hierarchical Set Abstraction modules provide a powerful and general-purpose building block for modern geometric deep learning pipelines.

Extensions and Improvements Numerous architectures have extended the PointNet++ paradigm to enhance expressiveness, efficiency, and scalability:

- PointNeXt [491] revisits PointNet++ with modern training techniques, simplified blocks, and residual connections for improved accuracy.

- DGCNN [684] introduces dynamic edge convolutions over local graphs, capturing fine-grained geometric relations across neighboring points.

- Point Transformers [789, 702] apply attention mechanisms to model long-range interactions in the point set, enabling context-aware reasoning.

These models now underpin many 3D perception systems, spanning applications in classification, segmentation, shape generation, and scene understanding.

Toward Structured Representations While point clouds offer an efficient and flexible surface representation, they lack explicit connectivity. This motivates the transition toward structured outputs such as triangle meshes and implicit surfaces, which support physically grounded operations like rendering, simulation, and editing.

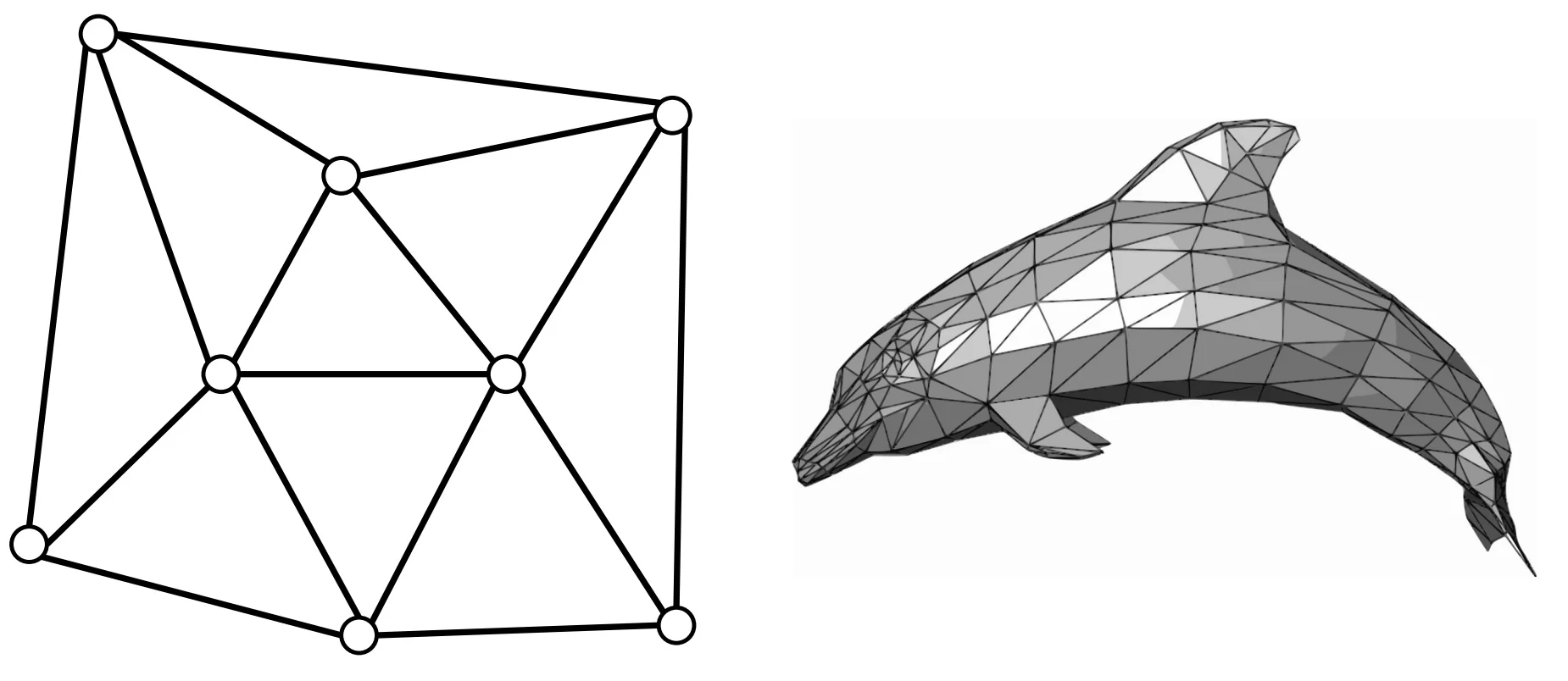

23.6 Triangle Meshes for 3D Shape Modeling

Triangle meshes are among the most widely used representations for 3D shapes in computer graphics, simulation, and geometric learning. A triangle mesh explicitly defines the surface of a 3D object using a finite set of vertices and faces. Let \(\mathcal {V} = \{ \mathbf {v}_i \in \mathbb {R}^3 \mid i = 1, \ldots , V \}\) denote the set of 3D vertex coordinates, and let \(\mathcal {F} = \{ (i, j, k) \mid i, j, k \in [1, V] \}\) denote the set of triangular faces, each indexed by three vertices.

This representation defines a piecewise-linear manifold embedded in 3D, enabling efficient rendering and geometric reasoning. Each face defines a planar triangle bounded by edges, and the entire mesh approximates a continuous surface.

Advantages of Triangle Meshes Triangle meshes are the standard in real-time and offline 3D applications due to several key properties:

- Surface explicitness: Meshes represent the actual 2D surface geometry embedded in 3D, facilitating accurate surface-based computations such as rendering, shading, and physical simulation.

- Adaptive resolution: Large triangles can be used in smooth regions, while dense subdivisions can capture high-curvature or detailed regions, yielding compact yet expressive representations.

- Rich annotations: Meshes can carry per-vertex attributes such as surface normals, color, and texture coordinates, which are interpolated over the mesh faces for shading and alignment.

Despite their efficiency, predicting triangle meshes from raw data (e.g., RGB images or point clouds) presents significant challenges: the output structure is non-Euclidean, connectivity must be preserved, and operations such as upsampling or interpolation are nontrivial. The next subsection introduces a model that addresses these challenges through learned graph-based mesh deformation.

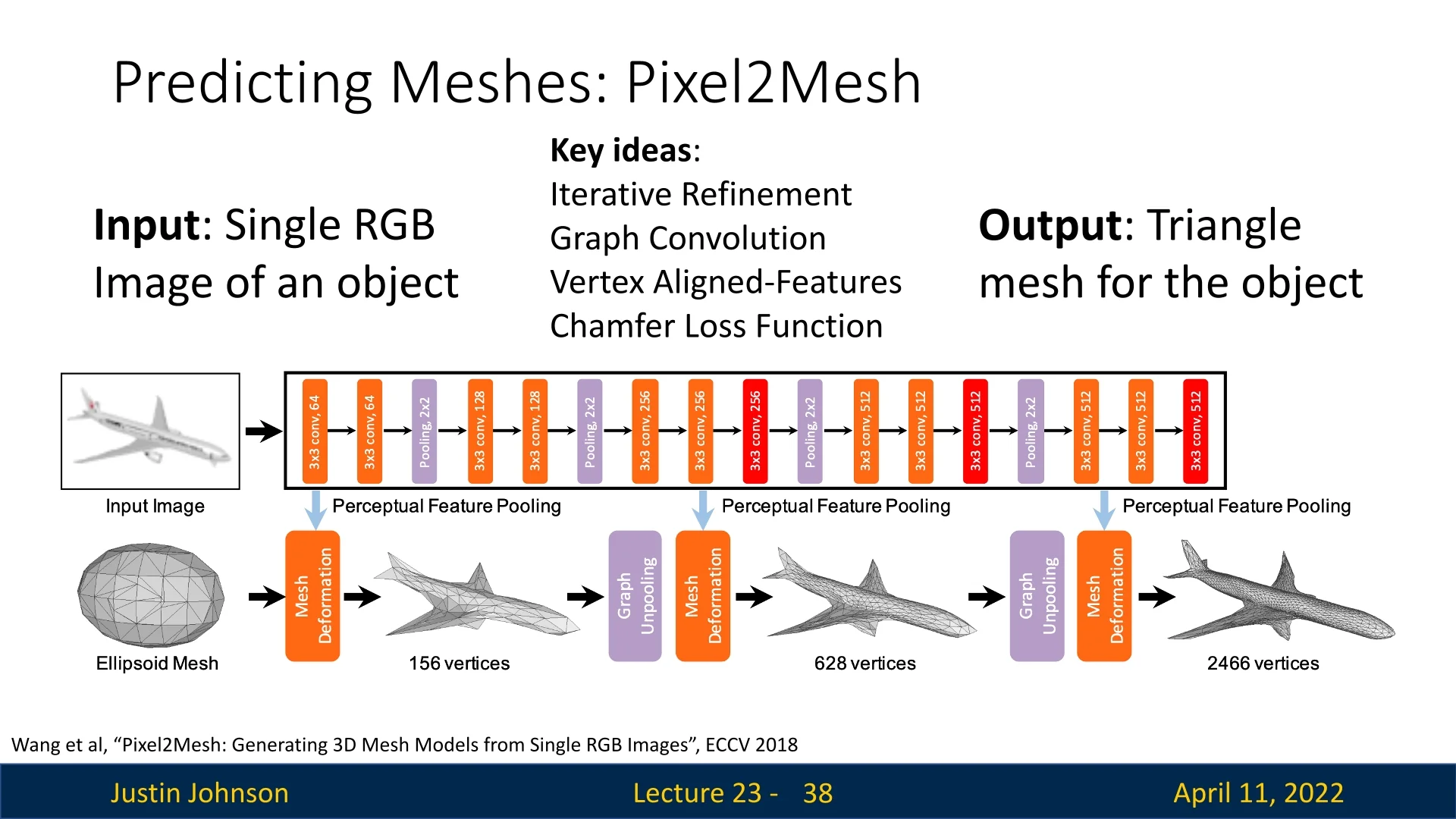

23.6.1 Pixel2Mesh: Predicting Triangle Meshes

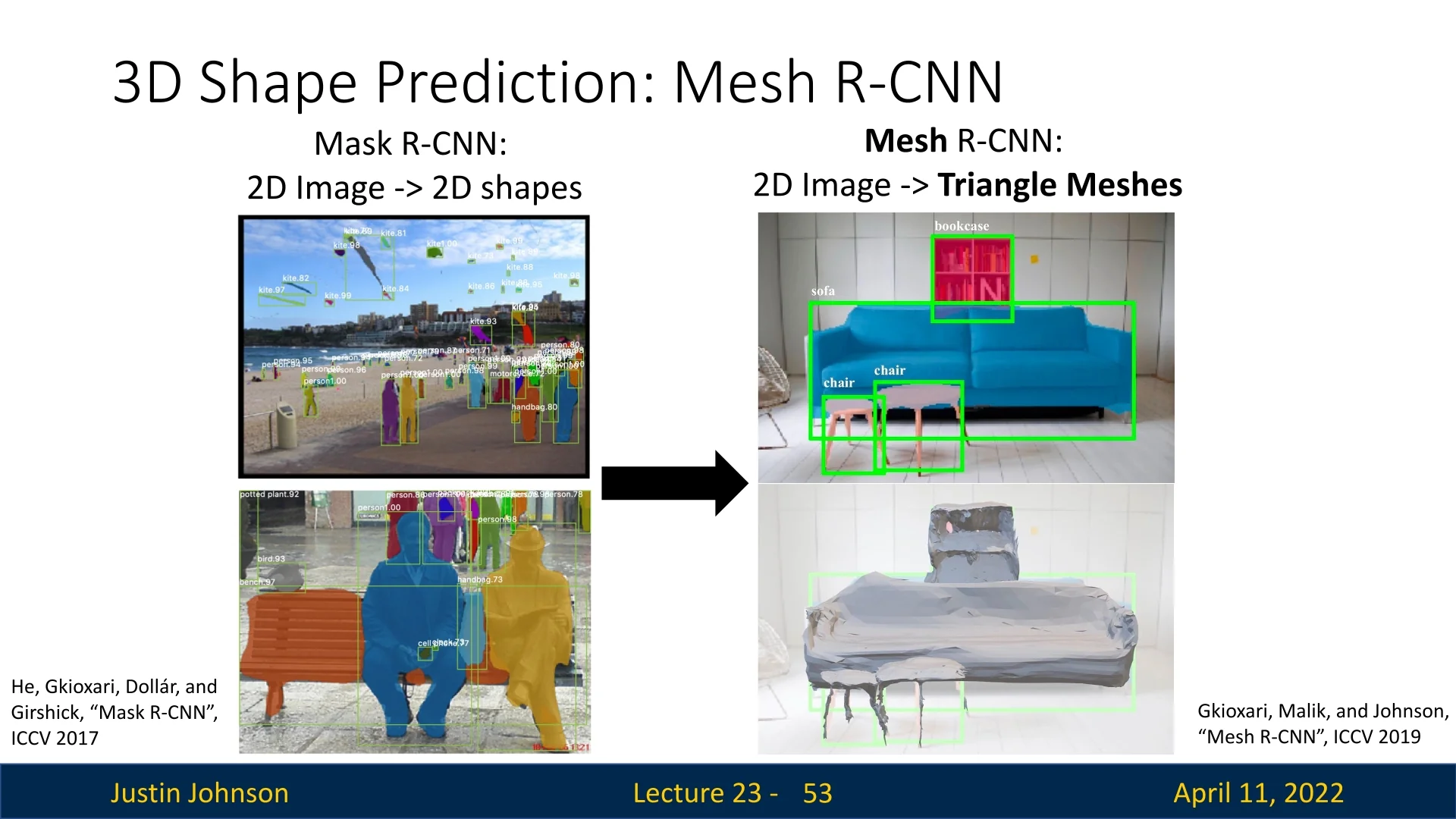

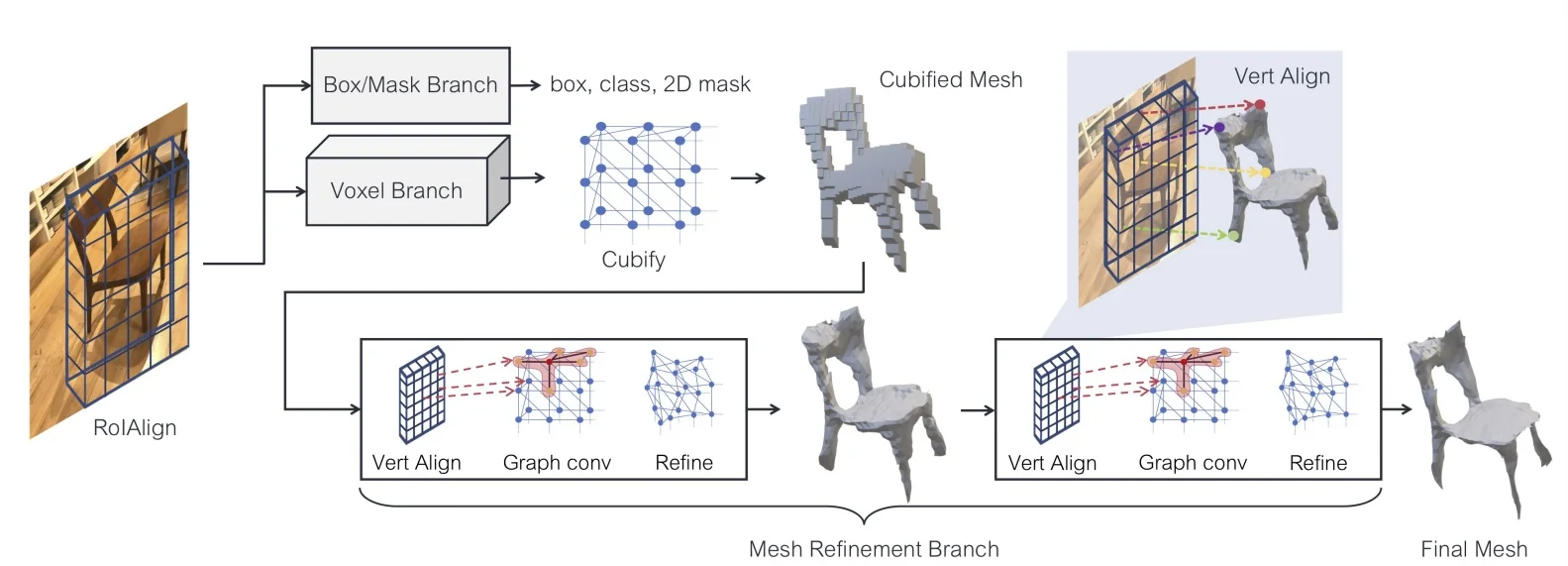

Pixel2Mesh [665] is a landmark method for generating 3D triangle meshes directly from a single RGB image. Unlike voxel-based approaches—which scale cubically in memory—or point cloud methods—which lack surface connectivity and require post-processing to extract usable geometry—Pixel2Mesh predicts structured mesh outputs: surfaces defined by vertices, edges, and faces. This makes it particularly suitable for applications that require explicit topology, such as simulation, CAD, or rendering.

Pre-Pixel2Mesh Landscape Prior to mesh-based methods, 3D learning architectures primarily explored two output formats:

- Voxel grids: Compatible with 3D convolutions and spatial reasoning, but constrained by high memory usage. Even modest resolutions (e.g., \(64^3\)) require hundreds of thousands of cells, limiting detail.

- Point clouds: More efficient and flexible, but inherently unstructured. Without connectivity, they cannot express surface geometry directly, making downstream tasks such as meshing or simulation error-prone.

Core Proposition Pixel2Mesh offers a structurally informed alternative by modeling 3D shape as a deformable mesh graph. Starting from a fixed-topology, genus-0 template (typically an ellipsoid), the network learns to iteratively deform vertex positions to match the object depicted in the image. This progressive refinement approach reframes the task: instead of generating structure from scratch, the model predicts residual displacements—small, local adjustments to an existing shape. This both simplifies learning and naturally preserves manifold topology, as the mesh’s connectivity remains unchanged across deformations.

Key Innovations Pixel2Mesh introduced a number of interlinked architectural ideas that made this formulation tractable:

- Coarse-to-Fine Refinement: The model deforms the mesh over multiple stages. After each deformation step, the mesh is upsampled—that is, each face is subdivided to increase resolution—enabling the network to model fine-grained surface detail while maintaining stability early on.

- Graph Convolution on Meshes: Deformations are computed using graph convolutional networks (GCNs), which aggregate information across neighboring vertices based on mesh connectivity. This allows localized, topology-aware reasoning.

- Vertex-Aligned Features: To connect 2D image content with the 3D mesh, the model projects each vertex onto the image plane and samples CNN features at the corresponding location. These features are passed to the GCN to guide deformation, grounding mesh updates in visual evidence.

-

Chamfer Distance for Mesh Supervision: Pixel2Mesh supervises mesh prediction by comparing the predicted vertex set \( \mathcal {V} \subset \mathbb {R}^3 \) to a ground-truth point cloud \( \mathcal {S}_{\mbox{gt}} \) using the symmetric Chamfer Distance: \[ \mathcal {L}_{\mbox{Chamfer}} = \sum _{x \in \mathcal {V}} \min _{y \in \mathcal {S}_{\mbox{gt}}} \|x - y\|_2^2 + \sum _{y \in \mathcal {S}_{\mbox{gt}}} \min _{x \in \mathcal {V}} \|x - y\|_2^2. \]

Although simple and differentiable, this loss only supervises vertex positions and ignores the interiors of mesh faces—potentially allowing distortions like sagging or warping between correctly placed vertices.

Later work, such as GEOMetrics [574], improves on this by comparing point clouds sampled from the entire predicted surface, offering finer surface-level supervision.

High-Level Pipeline Pixel2Mesh transforms a single RGB image into a 3D triangle mesh through a progressive mesh deformation pipeline that unifies convolutional image features and geometric mesh reasoning. The method begins with two inputs: a 2D image and a coarse, genus-0 mesh template (typically an ellipsoid centered in front of the camera). This template serves as the canonical starting point for all reconstructions and encodes strong priors on manifoldness and mesh topology.

The network refines this initial mesh in three stages, each consisting of deformation, unpooling, and feature update modules. The process is structured as follows:

- 1.

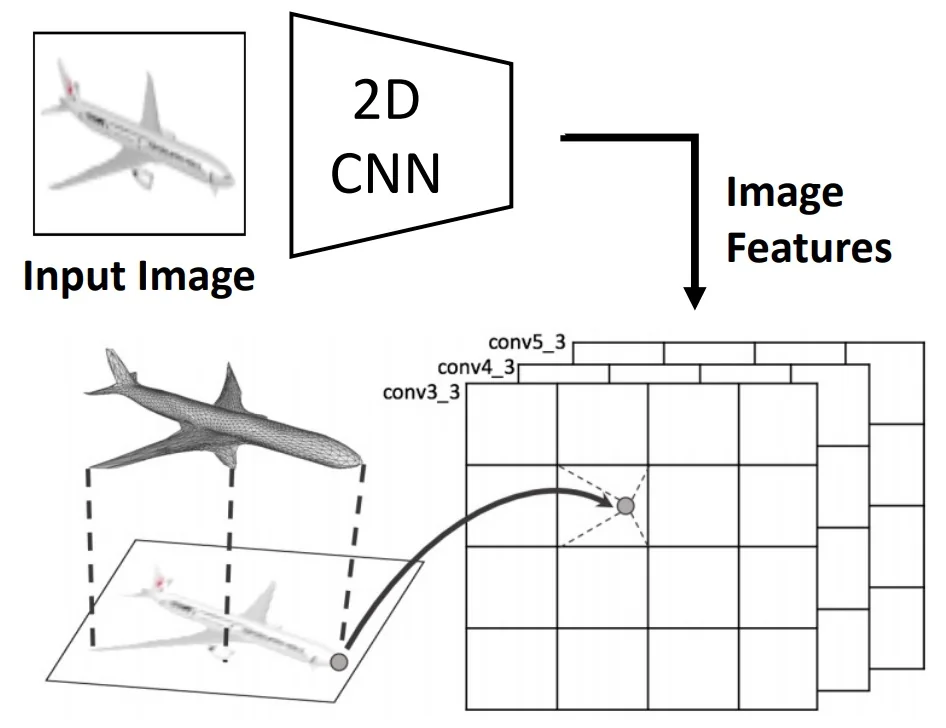

- Image Feature Extraction: A 2D convolutional backbone (e.g., VGG-16) processes the input RGB image to extract multi-scale feature maps from intermediate layers (e.g., conv3_3, conv4_3, conv5_3). These maps encode both low-level textures and high-level semantic patterns, offering a rich perceptual signal that guides the 3D reconstruction process.

- 2.

- Vertex-to-Image Feature Pooling: Each mesh vertex is projected onto the image plane using known camera intrinsics. At the projected 2D coordinates, features are bilinearly sampled from the image’s multi-level CNN maps and concatenated to the vertex’s current geometric descriptor. This projection-based pooling serves as the only available cue during inference, anchoring the 3D reconstruction to image evidence. It provides the graph network with localized appearance information, helping it decide where and how to displace each vertex and add detail.

- 3.

- Graph Convolution for Deformation: The mesh is represented as a graph, with vertices as nodes and edges defined by mesh connectivity. A Graph Convolutional Network (GCN) processes this structure, updating each vertex’s feature vector by aggregating information from its neighbors. The GCN is composed of multiple layers, expanding each vertex’s receptive field and enabling contextual reasoning across the surface. Crucially, the image-aligned features from the pooling step guide the GCN’s residual predictions—telling the network how to deform the shape in 3D to better match the visual evidence.

- 4.

- Graph Unpooling for Resolution Increase: To increase geometric detail, the mesh is upsampled after each deformation stage using edge-based unpooling. New vertices are inserted at the midpoints of edges, and connectivity is updated to preserve the mesh’s manifold structure. The positions and features of new vertices are initialized by averaging their endpoints, allowing the network to seamlessly enrich surface detail without altering global shape or topology.

- 5.

- Iterative Refinement: The refined mesh is passed through multiple deformation stages, each repeating the cycle of vertex-to-image feature pooling (Step 2), GCN-based displacement prediction (Step 3), and graph unpooling (Step 4). This iterative coarse-to-fine strategy begins with a low-resolution mesh that captures global structure—benefiting from short graph diameters and large effective receptive fields—and progressively increases resolution to recover fine surface details. As the mesh converges toward the target shape, vertex projections align more accurately with relevant regions in the image, enhancing the quality of sampled features and enabling increasingly precise geometric corrections at each stage.

This multi-stage architecture offers a powerful compromise between efficiency and fidelity. The low-resolution mesh allows efficient global shape reasoning in early layers, while unpooling introduces degrees of freedom necessary for high-resolution surface detail. By integrating 2D image cues at every stage and learning deformation through graph-based reasoning, Pixel2Mesh generates detailed, topologically consistent 3D meshes from a single image.

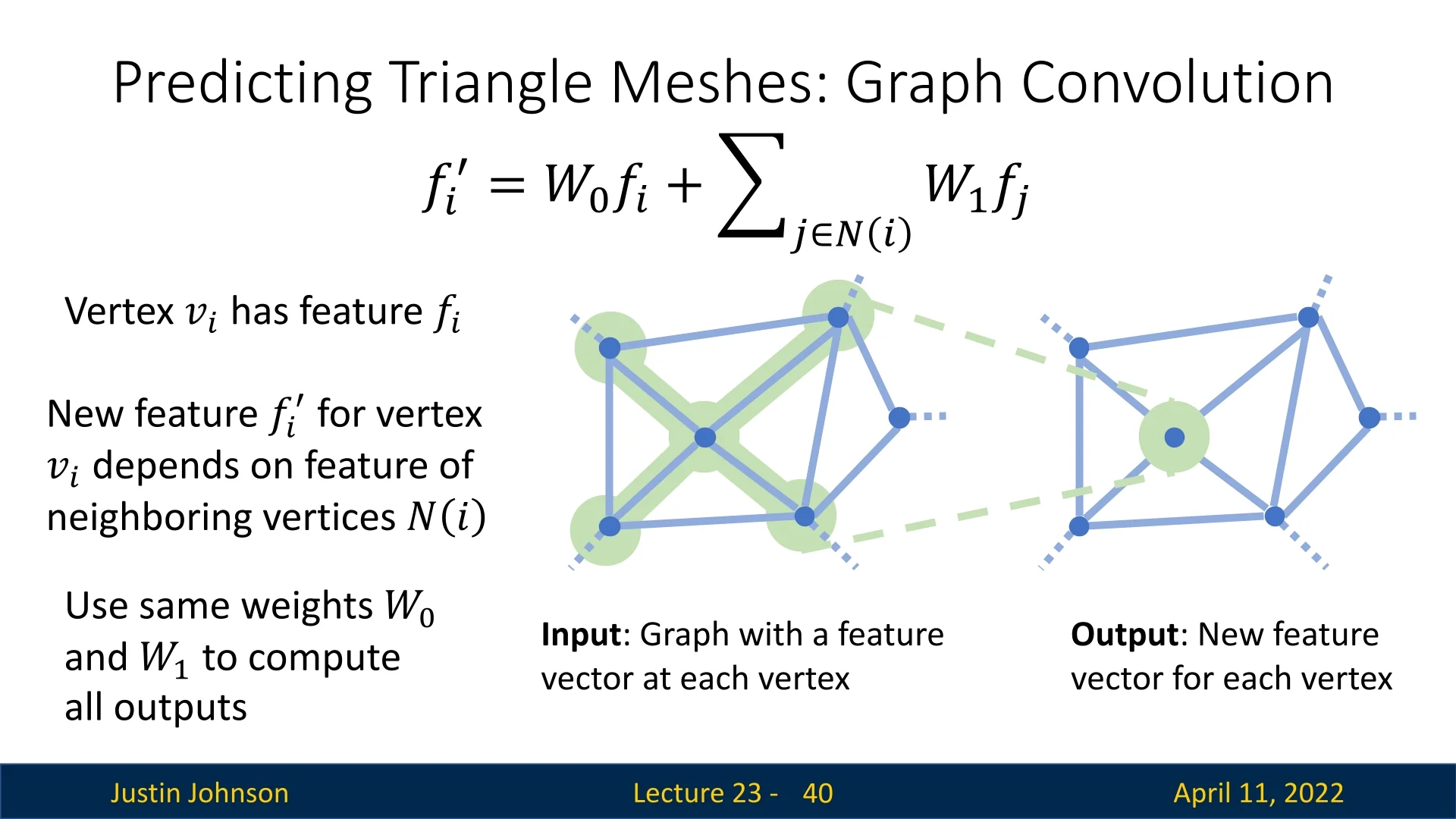

Graph-Based Feature Learning A core challenge in learning from 3D meshes is that they are non-Euclidean structures. Unlike images or voxels, which lie on regular grids with fixed-size neighborhoods and translation-invariant kernels, triangle meshes consist of irregularly connected vertices with no global coordinate frame. To apply learning methods to this setting, Pixel2Mesh treats the mesh as a graph \( \mathcal {G} = (\mathcal {V}, \mathcal {E}) \), where:

- Nodes (\( \mathcal {V} \)) are mesh vertices. Each vertex \( i \in \mathcal {V} \) is assigned a feature vector \( \mathbf {f}_i \in \mathbb {R}^d \), initialized using its 3D coordinates \( \mathbf {v}_i \in \mathbb {R}^3 \), and later enriched through graph-based message passing.

- Edges (\( \mathcal {E} \)) encode mesh connectivity. Two nodes \( i \) and \( j \) share an edge if their corresponding vertices are adjacent on a triangle face. This forms the local neighborhood \( \mathcal {N}(i) \) around each vertex.

To extend the receptive field across the mesh and support complex shape reasoning, Pixel2Mesh stacks multiple such layers into a 14-layer Graph Convolutional ResNet (G-ResNet). The inclusion of residual (skip) connections helps stabilize optimization, facilitates deeper architectures, and allows low-level geometry to be preserved and reused throughout the network. As features propagate through the GCN, each vertex gains access to increasingly broader geometric context—essential for learning coherent deformations informed by both local surface cues and global object structure.

This graph-based feature hierarchy ultimately enables each vertex to predict a residual 3D displacement vector \( \Delta \mathbf {v}_i \), which updates its position without altering mesh connectivity. Subsequent parts detail how these features are fused with 2D image evidence and used to deform the mesh toward the target shape.

To increase the expressive capacity of the network, Pixel2Mesh stacks 14 such layers into a deep Graph Convolutional ResNet (G-ResNet). This depth enables each vertex to aggregate information from increasingly distant nodes, expanding its receptive field over the graph. Unlike grids, graphs can have highly irregular connectivity, and so reaching distant vertices may require many layers of message passing. Skip connections—added between GCN layers—help mitigate this by stabilizing gradient flow during training and facilitating feature reuse. In the context of mesh deformation, these residual paths are particularly useful: they allow the network to retain low-level spatial signals (e.g., coarse geometry or symmetric structures) while progressively layering on fine-grained, high-level shape refinements.

Predicting Vertex Positions via Graph Projection At the end of each mesh deformation block, the G-ResNet outputs a refined feature vector \( \mathbf {f}_i \in \mathbb {R}^d \) for each vertex \( i \). These features encode both geometric structure (through message passing over the mesh) and semantic cues (through vertex-aligned image features). To convert these features into updated vertex coordinates, Pixel2Mesh applies a simple yet crucial operation: a final linear layer referred to as the graph projection layer.

Formally, the new 3D position of each vertex is predicted as: \[ \mathbf {v}_i^{\mbox{new}} = W_{\mbox{proj}} \mathbf {f}_i, \] where \( W_{\mbox{proj}} \in \mathbb {R}^{d \times 3} \) is a learnable weight matrix shared across all vertices. This transformation maps the high-dimensional vertex features directly into absolute 3D space.

Importantly, this step does not compute or apply a residual displacement. The network predicts the final 3D position outright. Although this may seem counterintuitive—many deformation-based models favor residual updates for stability—the Pixel2Mesh architecture learns this coordinate regression implicitly, leveraging the structured feature learning of the G-ResNet. The underlying mesh structure and feature propagation already encode strong geometric priors, making direct position regression viable and effective.

Throughout this process, the mesh’s topology remains fixed: only vertex positions are updated, not their connectivity. This allows each deformation block to operate over a stable graph structure while progressively refining the mesh surface. After this coarse shape is aligned with the image, graph unpooling increases mesh resolution by inserting new vertices at edge midpoints. Subsequent deformation blocks then focus on finer-scale geometry, aided by a denser mesh and more localized 2D image alignment.

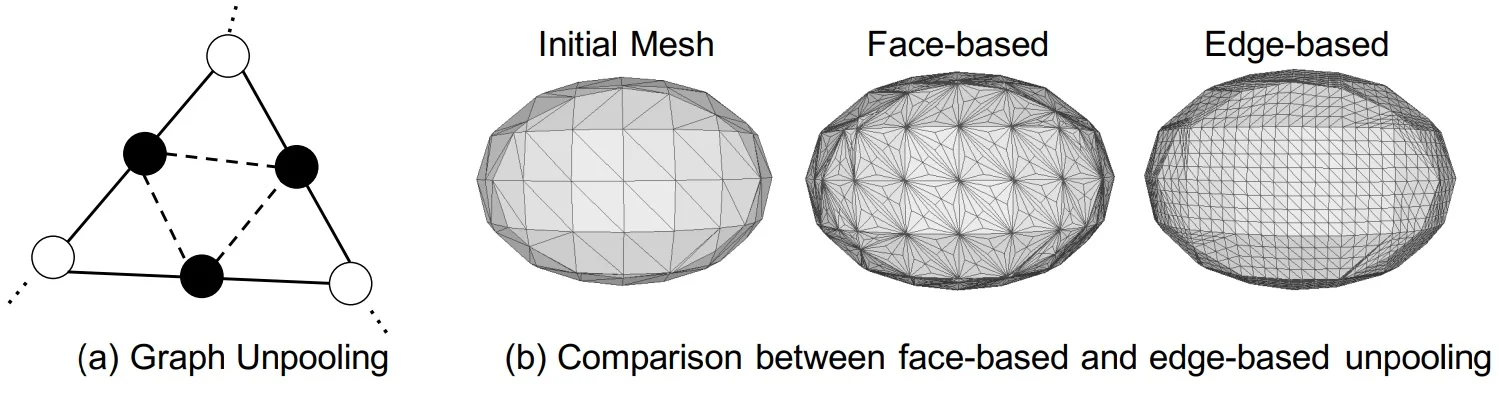

Edge-Based Graph Unpooling for Mesh Resolution Refinement After each stage of coarse deformation, Pixel2Mesh increases the mesh resolution to allow more fine-grained geometric refinement. This is achieved via a carefully designed graph unpooling operation that avoids the artifacts common in naive subdivision schemes. Instead of inserting new vertices at triangle centroids (which creates low-degree, poorly connected nodes), Pixel2Mesh uses an edge-based unpooling strategy inspired by classical mesh subdivision methods.

The unpooling procedure is as follows:

- A new vertex is inserted at the midpoint of each edge in the mesh.

- This new vertex is connected to the two endpoints of the edge.

- For every triangle in the original mesh, the three mid-edge vertices are connected to form a new inner triangle.

This process subdivides each original triangle into four smaller triangles and preserves regularity in vertex degree and local topology. To initialize the features of the new mid-edge vertices, the network simply averages the features of the parent vertices: \[ \mathbf {f}_{\mbox{new}} = \frac {1}{2}(\mathbf {f}_i + \mathbf {f}_j), \] where \( i \) and \( j \) are the endpoints of the edge. This yields smooth and stable feature transitions for subsequent GCN layers.

This coarse-to-fine unpooling scheme allows Pixel2Mesh to expand its receptive field and prediction granularity in tandem. The three-stage pipeline uses meshes with 156, 628, and finally 2466 vertices—an architecture that mirrors the increasing complexity of the shape being reconstructed. Early blocks handle the “big picture,” while later blocks focus on refining sharp contours, smooth curvatures, and small geometric details.

Image-to-Mesh Feature Alignment A key innovation in Pixel2Mesh is its ability to guide 3D mesh deformation using 2D visual cues extracted from the input image. This involves bridging two fundamentally different data domains: the regular, grid-aligned structure of 2D images and the irregular, graph-based structure of 3D meshes. Pixel2Mesh realizes this connection through a Perceptual Feature Pooling module, which aligns each mesh vertex with semantically relevant image features and dynamically refines that alignment at each deformation stage.

The process begins with a pretrained VGG-16 network (frozen during training), used to extract multi-scale image features from the input RGB image. Features are taken from three intermediate layers—conv3_3, conv4_3, and conv5_3—which together capture both fine textures and abstract semantics. These layers yield feature maps at decreasing spatial resolutions and increasing channel dimensionality.

For each vertex \( i \) in the current mesh, the following steps are performed:

- 1.

- Projection to the Image Plane: The 3D vertex position \( \mathbf {v}_i = (x_i, y_i, z_i) \in \mathbb {R}^3 \) is projected to 2D image coordinates using known perspective camera intrinsics: \[ (u_i, v_i) = \left ( \frac {f_x x_i}{z_i} + c_x,\; \frac {f_y y_i}{z_i} + c_y \right ). \] This maps the 3D point to the location on the image where it is expected to appear.

- 2.

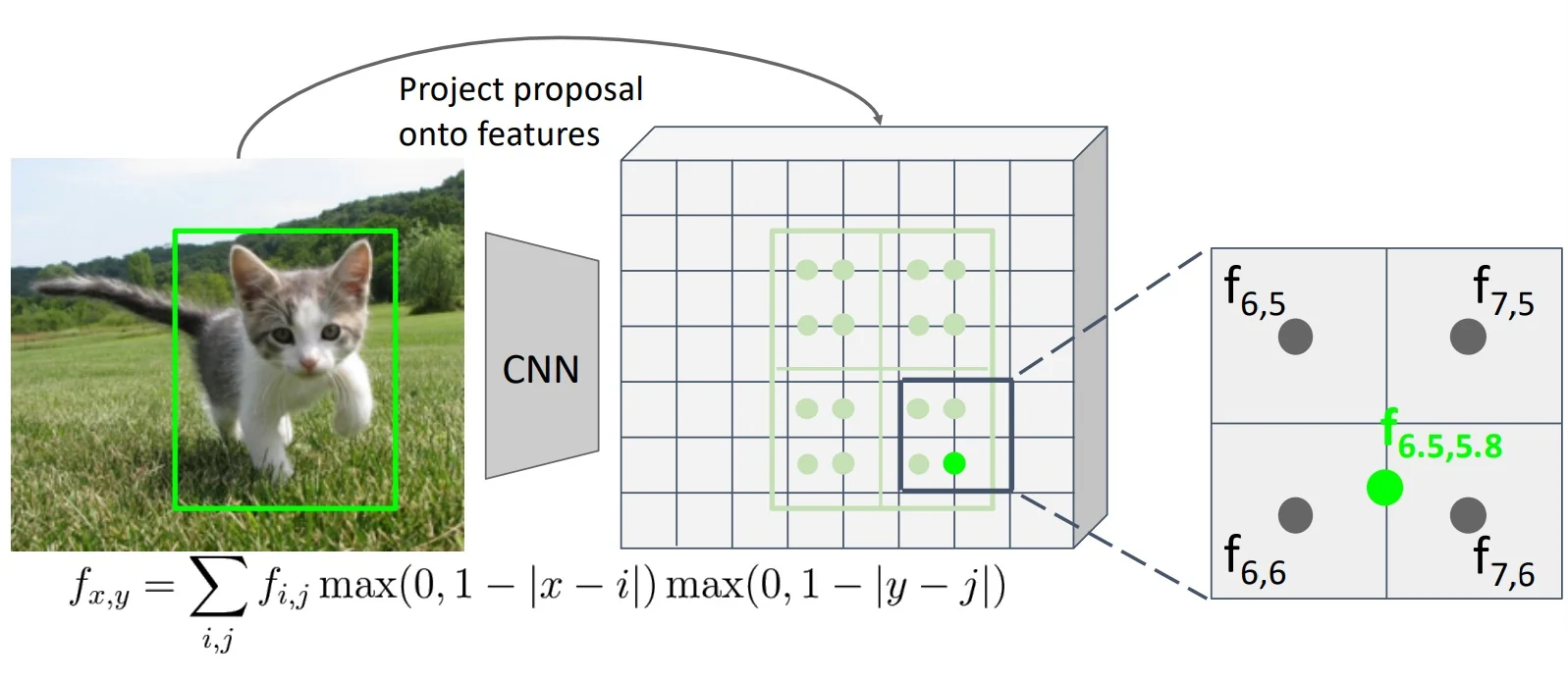

- Bilinear Feature Sampling: At each projected coordinate \( (u_i, v_i) \), bilinear

interpolation is applied to the VGG feature maps to retrieve

image-aligned descriptors. This interpolation ensures that features

can be sampled at subpixel resolution and maintains differentiability

throughout the pipeline.

Figure 23.21: Bilinear interpolation retrieves CNN features at non-integer projected positions. This mechanism resembles RoIAlign and allows smooth vertex-to-image alignment. - 3.

- Multi-Scale Feature Fusion: The sampled feature vectors from conv3_3, conv4_3, and conv5_3 are concatenated to form a unified descriptor \( \mathbf {f}^{\mbox{img}}_i \in \mathbb {R}^{1280} \) (e.g., 256 + 512 + 512 channels). This vector encodes both local appearance and high-level semantics around the vertex projection.

- 4.

- Fusion with Graph Features: The perceptual feature \( \mathbf {f}^{\mbox{img}}_i \) is concatenated with the vertex’s geometric feature \( \mathbf {f}_i \in \mathbb {R}^d \), as computed by previous graph convolution layers. The resulting fused descriptor is then passed to the next G-ResNet deformation block to guide shape refinement.

Importantly, this perceptual pooling process is not static—it is repeated at the beginning of every mesh deformation block using the current mesh geometry. This creates a dynamic feedback loop:

- In the first stage, vertex projections from the initial ellipsoid are poorly aligned with the object, so pooled features are coarse and ambiguous.

- After the first deformation block updates vertex positions, the mesh becomes better aligned with the image.

- When pooling is reapplied in the next stage, projections land on more semantically meaningful image regions, yielding more informative features.

- This cycle continues, with improved mesh geometry enabling better feature alignment, which in turn enables more precise deformations.

This iterative loop—deform → reproject → repool—is central to Pixel2Mesh’s effectiveness. Rather than relying on static image features, the model continuously refines its 2D–3D correspondence, allowing later stages to make sharper, semantically aware deformations based on increasingly accurate visual cues. The tight coupling of image perception and geometric reasoning enables the network to generate high-fidelity 3D surfaces even from a single image input.

Loss Function for Mesh Prediction in Pixel2Mesh

To guide the deformation of a coarse mesh into a high-quality 3D reconstruction, Pixel2Mesh employs a composite loss function that balances geometric accuracy, surface regularity, and structural plausibility. The loss is applied not only to the final output but also at each intermediate stage in the coarse-to-fine refinement pipeline.

Primary Objective: Chamfer Distance (Vertex-to-Vertex) The central supervision signal is the symmetric Chamfer Distance between the predicted mesh vertices \( V_{\mbox{pred}} \) and a set of ground-truth vertices \( V_{\mbox{gt}} \), both sampled from respective meshes:

\[ \mathcal {L}_{\mbox{Chamfer}} = \sum _{v \in V_{\mbox{pred}}} \min _{u \in V_{\mbox{gt}}} \|v - u\|_2^2 + \sum _{u \in V_{\mbox{gt}}} \min _{v \in V_{\mbox{pred}}} \|u - v\|_2^2 \]

This term ensures that each predicted vertex lies close to some part of the ground-truth surface, and vice versa. While originally designed for unordered point sets, this metric is used here as a surrogate for surface similarity. It is efficient and differentiable, but has limitations—it evaluates only the positions of vertices and not the geometry of faces.

Laplacian Smoothness Loss To enforce local geometric coherence and prevent unrealistic surface artifacts, Pixel2Mesh introduces a Laplacian regularization term that encourages smooth vertex deformations. This loss penalizes deviations in the Laplacian coordinates of each vertex before and after deformation. The Laplacian coordinate of vertex \( i \) is defined as the offset between its position and the average of its immediate neighbors:

\[ \delta _i = \mathbf {v}_i - \frac {1}{|\mathcal {N}(i)|} \sum _{j \in \mathcal {N}(i)} \mathbf {v}_j \]

After a deformation block updates the mesh to new vertex positions \( \mathbf {v}_i' \), the updated Laplacian coordinate is denoted \( \delta _i' \). The Laplacian loss penalizes the change in these coordinates:

\[ \mathcal {L}_{\mbox{Lap}} = \sum _i \left \| \delta _i' - \delta _i \right \|_2^2 \]

This loss serves a dual purpose depending on the stage of mesh refinement. In early stages, when the mesh is still close to the initial ellipsoid, the Laplacian coordinates are small and uniform; the loss encourages smooth, globally consistent deformations, helping prevent tangled or self-intersecting geometry. In later stages, once the mesh has learned a plausible coarse shape, the Laplacian coordinates reflect learned local structure. Penalizing changes to these coordinates helps preserve previously learned surface details, ensuring that finer deformations do not overwrite or distort earlier predictions.

Intuitively, this loss encourages vertices to move together with their neighbors, discouraging isolated spikes, noisy fluctuations, or jagged artifacts—especially in high-curvature or thin regions. As such, it acts as a learned shape stabilizer throughout the deformation pipeline.

Edge Length Regularization As the mesh undergoes progressive refinement through unpooling, Pixel2Mesh introduces additional vertices and edges to increase spatial resolution. While this enables finer geometric detail, it also introduces new degrees of freedom that can destabilize the mesh—especially during early training or coarse-to-fine transitions. Without proper constraints, vertices may drift far from their neighbors, forming “flying vertices” connected by abnormally long edges. To suppress such artifacts, Pixel2Mesh applies an edge length regularization term, defined as:

\[ \mathcal {L}_{\mbox{edge}} = \sum _{(i,j) \in \mathcal {E}} \| \mathbf {v}_i - \mathbf {v}_j \|_2^2, \]

where \( \mathcal {E} \) is the set of all mesh edges at the current refinement stage. This loss penalizes the absolute squared length of each edge, thereby encouraging spatial coherence among neighboring vertices.

While this formulation is unnormalized in the original paper, its contribution to the overall loss is controlled via a fixed hyperparameter \( \lambda \), ensuring stability across deformation stages despite increasing edge count. Importantly, this term does not compare edge lengths to their prior values or enforce a canonical length. Instead, it acts as a dynamic local tether, discouraging over-extension without constraining the mesh to a rigid template.

This regularizer is especially critical immediately after graph unpooling. Newly added vertices—typically initialized at edge midpoints—are still trainable and unconstrained by prior geometry. The edge length loss ensures that their deformations remain consistent with the surrounding structure, preventing unstable stretching and promoting uniform vertex spacing.

Together with the Laplacian and normal consistency terms, this loss helps maintain the integrity of the mesh during deformation, guiding the network toward smooth, coherent, and physically plausible reconstructions.

Normal Consistency Loss To enhance visual quality and ensure correct surface orientation, a normal loss penalizes misalignment between predicted edges and ground-truth normals:

\[ \mathcal {L}_{\mbox{normal}} = \sum _i \sum _{j \in \mathcal {N}(i)} \left \langle v_i - v_j, \, n_q \right \rangle ^2 \]

Here, \( n_q \) is the normal at the closest point \( q \) on the ground-truth mesh to vertex \( v_i \). This loss encourages edges to lie tangent to the surface, improving shading behavior and geometric realism. It captures higher-order consistency beyond just vertex positions.

Total Loss The final loss combines all components with fixed scalar weights:

\[ \mathcal {L}_{\mbox{total}} = \mathcal {L}_{\mbox{Chamfer}} + \lambda _1 \mathcal {L}_{\mbox{normal}} + \lambda _2 \mathcal {L}_{\mbox{Lap}} + \lambda _3 \mathcal {L}_{\mbox{edge}} \]

Pixel2Mesh uses \(\lambda _1 = 1.6 \times 10^{-4}\), \(\lambda _2 = 0.3\), and \(\lambda _3 = 0.1\). These weights were selected empirically to ensure that geometric fidelity is prioritized while still promoting mesh regularity and perceptual realism.

Limitations and Future Directions While this loss formulation is effective, it has several shortcomings:

- Vertex-Only Supervision: The Chamfer loss evaluates only discrete vertex positions, not the full surface defined by mesh faces.

- Sagging Faces: Large triangles may sag or bulge between correctly placed corner vertices without incurring loss, as interior deviations are unobserved.

- Oversmoothing Risk: The combination of Laplacian and edge constraints may suppress sharp features or fine details if not balanced carefully.

- Triangulation Bias: Matching based on vertex positions can penalize geometrically similar surfaces with differing connectivity.

Later methods such as GEOMetrics address these issues by introducing surface-based sampling and differentiable point sampling from triangle interiors, allowing more accurate and complete loss computation over the full mesh surface.

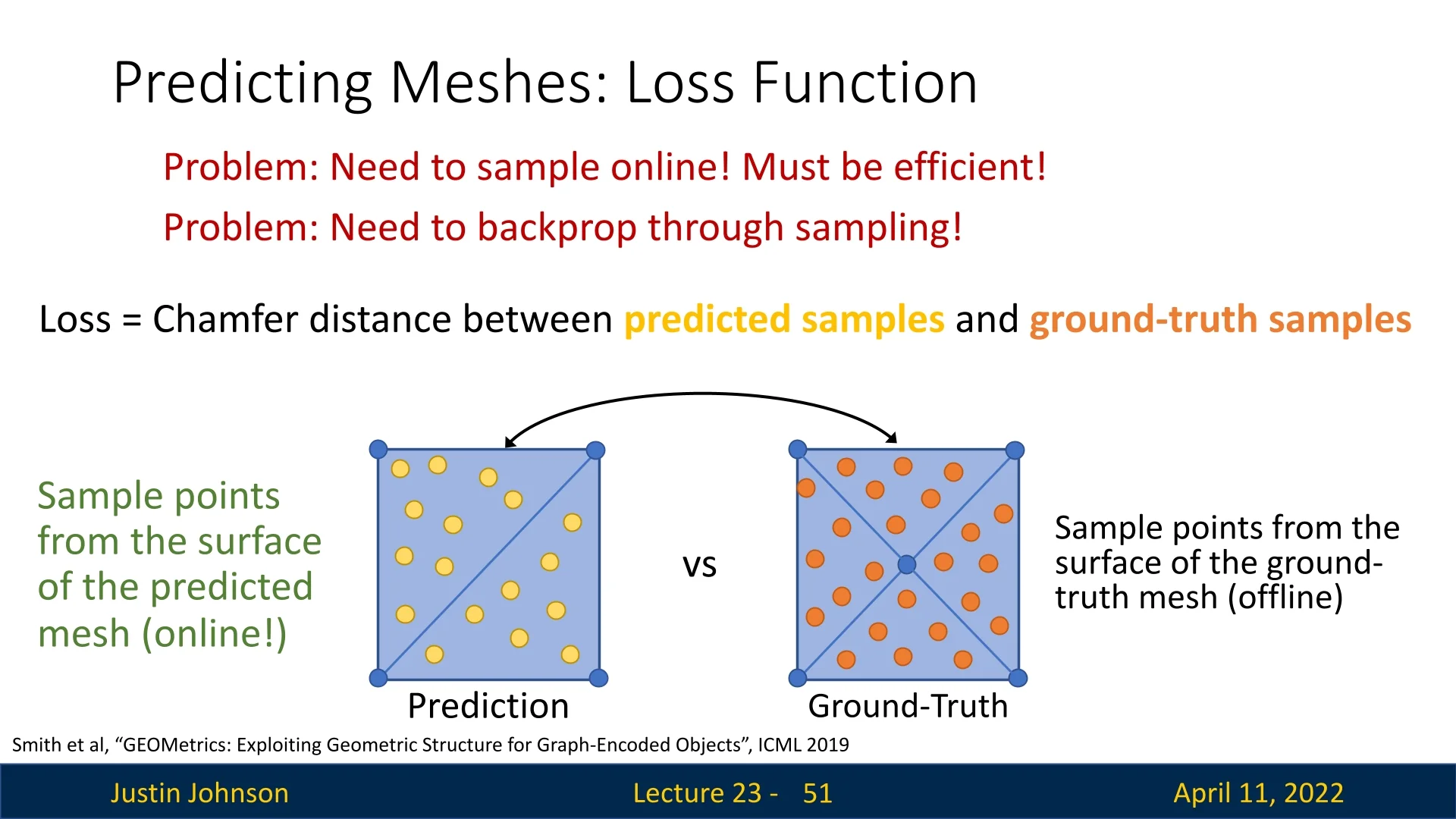

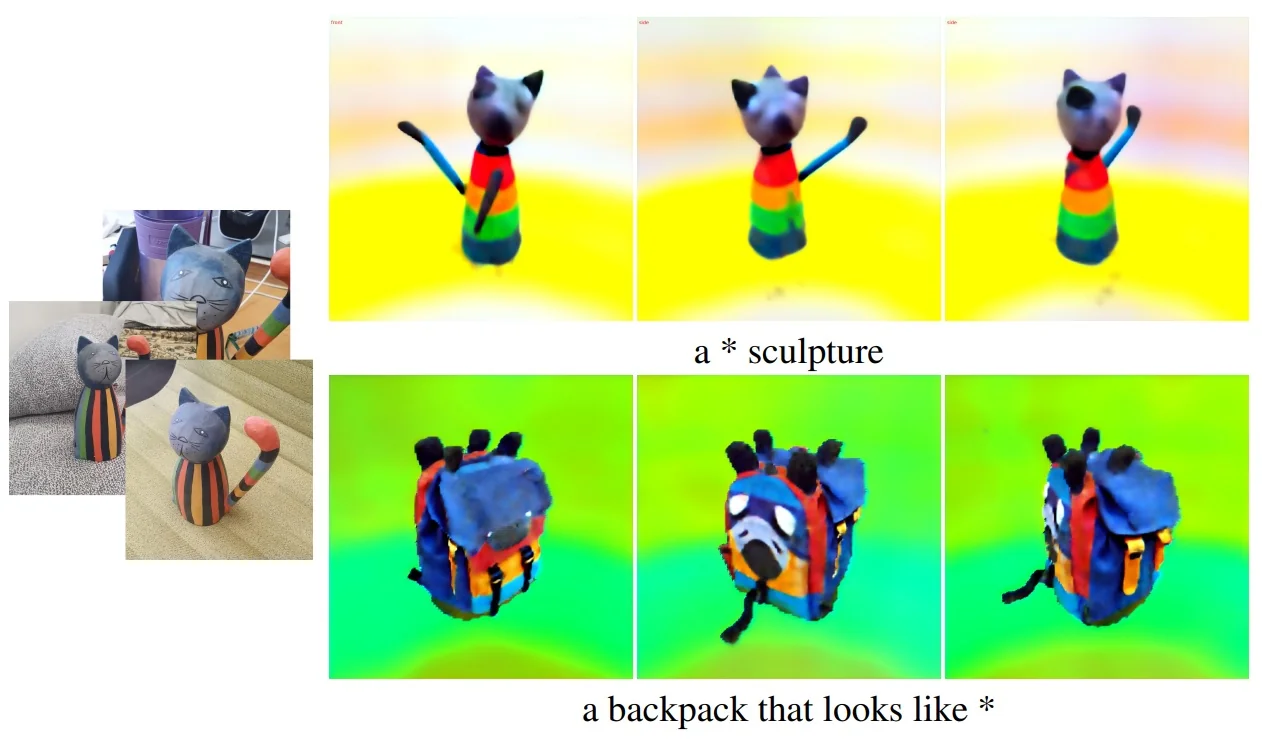

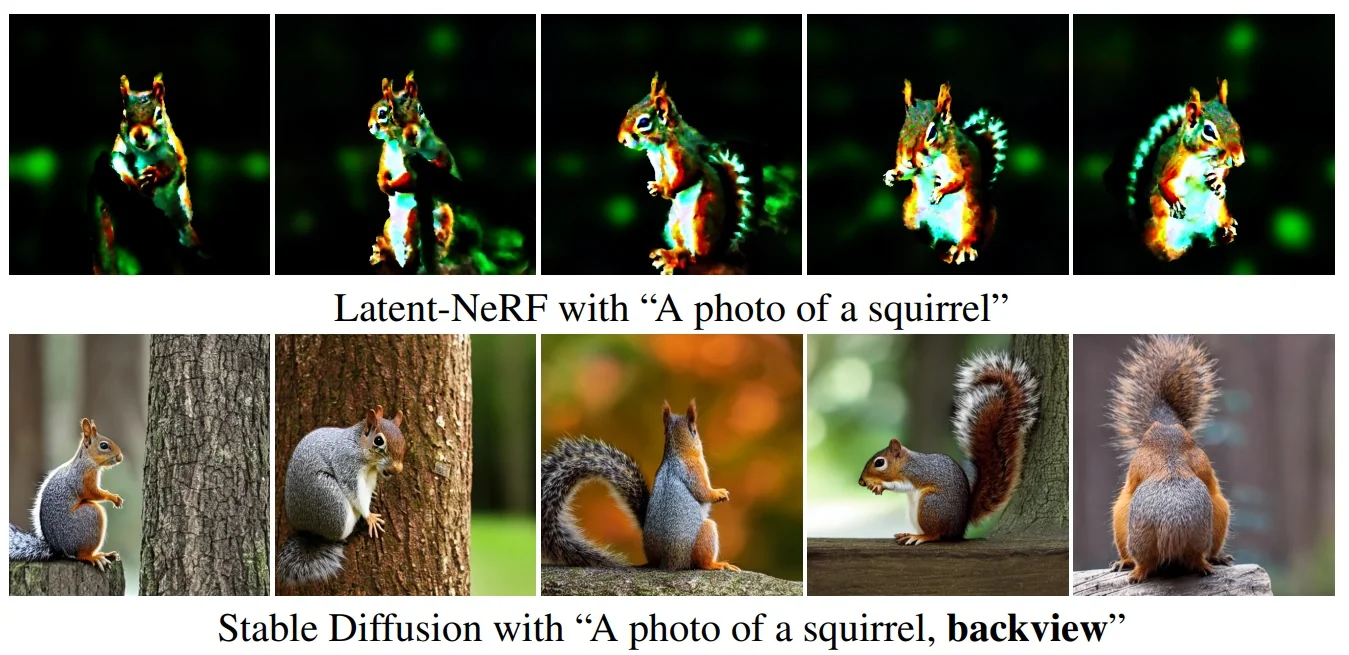

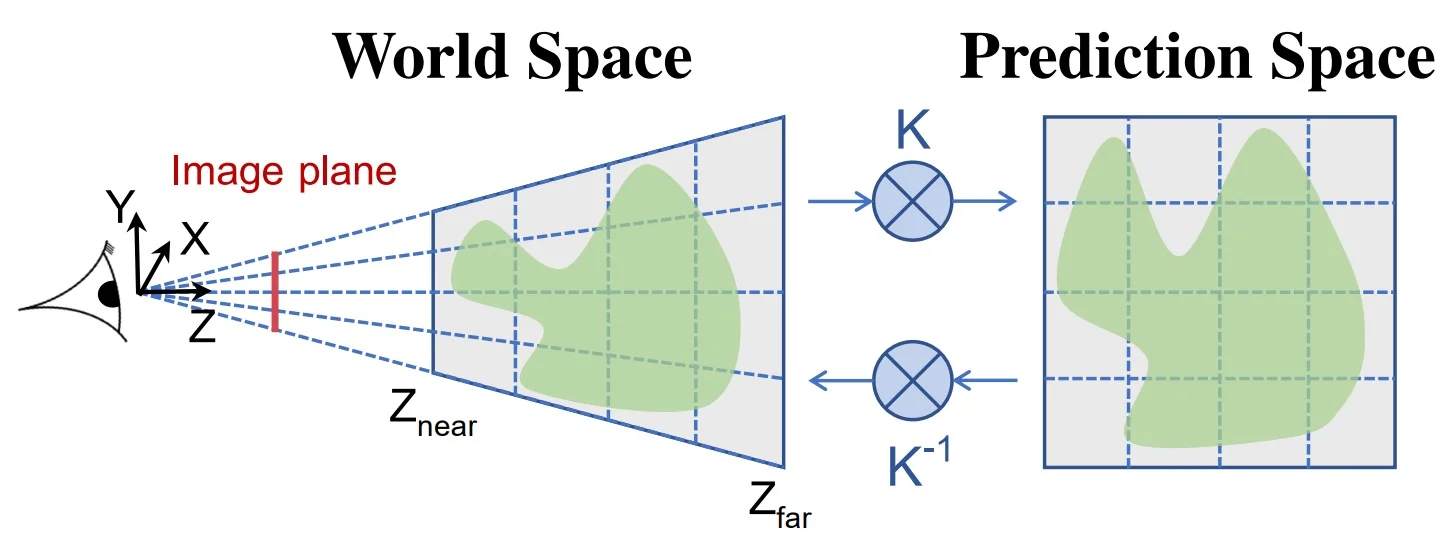

Enrichment 23.6.1.1: Differentiable Surface Sampling in GEOMetrics

Surface-to-Surface Comparison with Differentiable Sampling A central innovation in GEOMetrics is its replacement of vertex-based supervision with full surface-level comparison. Pixel2Mesh constrains only mesh vertex positions using a Chamfer loss against a fixed ground-truth point cloud, ignoring the geometry of the mesh faces that connect them. As a result, large triangles can sag or bulge without penalty as long as their corner vertices remain close to the sampled ground truth—leading to visible artifacts.

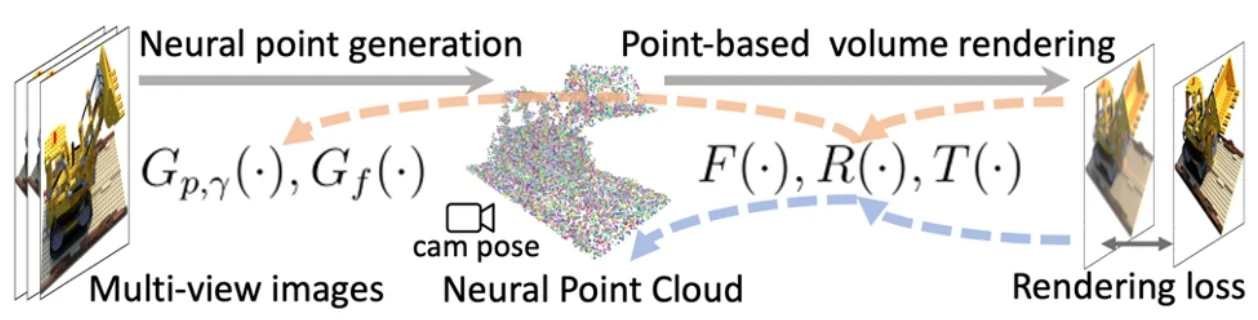

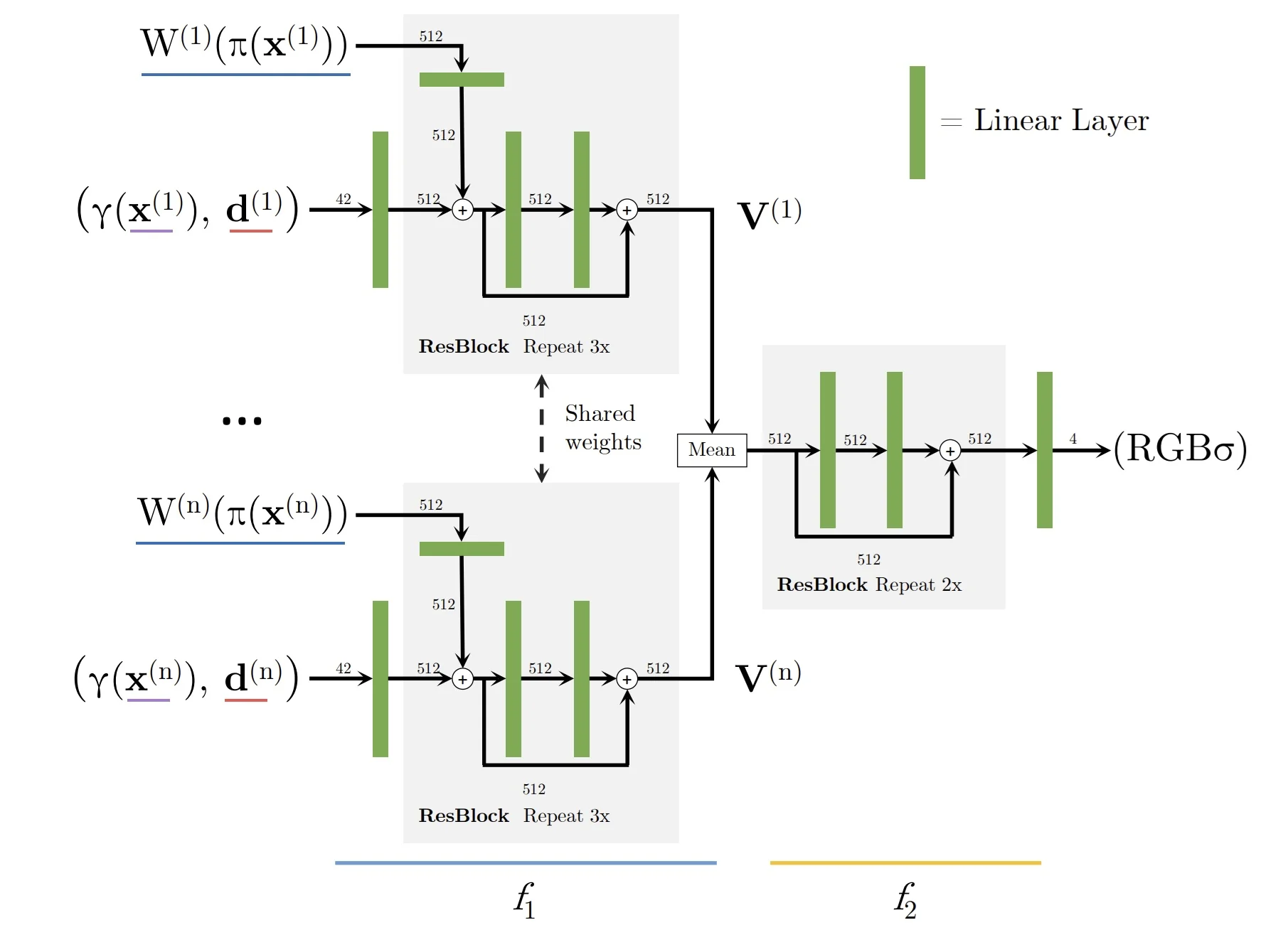

To resolve this, GEOMetrics computes a symmetric distance between dense point clouds sampled from the entire surface of both meshes. The primary loss during early training is the Point-to-Point Chamfer Distance: \[ \mathcal {L}_{\mbox{PtP}} = \sum _{p \in S_{\mbox{pred}}} \min _{q \in S_{\mbox{gt}}} \|p - q\|_2^2 + \sum _{q \in S_{\mbox{gt}}} \min _{p \in S_{\mbox{pred}}} \|q - p\|_2^2 \] Here, \( S_{\mbox{pred}} \) and \( S_{\mbox{gt}} \) are point clouds sampled online from the predicted and ground-truth meshes, respectively. This loss encourages every sampled point on one surface to be close to some point on the other, and vice versa—ensuring both coverage and correspondence. The symmetric form (sum of minimum distances in both directions) avoids degenerate solutions like mode collapse, where one shape covers the other but not vice versa.