Lecture 22: Self-Supervised Learning

22.1 Motivation and Definition

22.1.1 What is Self-Supervised Learning (SSL)?

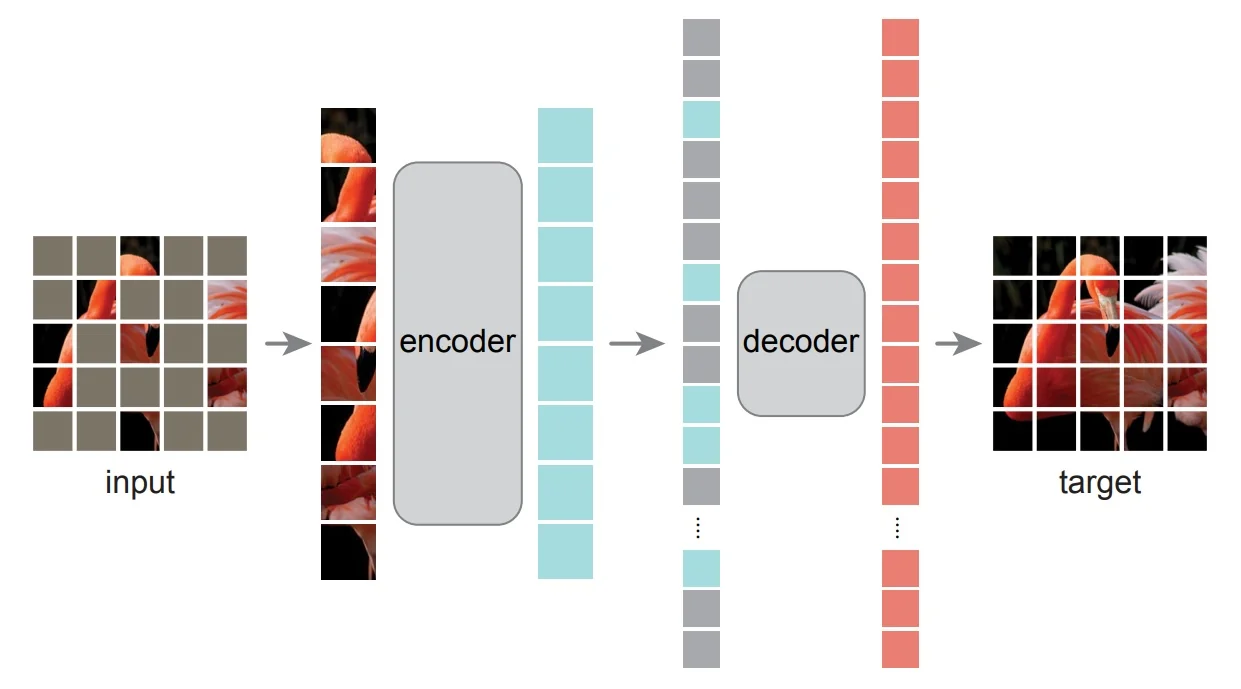

Learning Representations Without Labels Self-Supervised Learning (SSL) is a learning paradigm that allows models to learn from unlabeled data by solving automatically constructed tasks—known as pretext tasks—that do not require manual annotations. These tasks are derived from the raw input itself and are carefully designed to encourage the model to learn semantic structure and meaningful features that transfer well to standard supervised tasks such as image classification, object detection, or segmentation.

A central goal in SSL is to obtain a compact embedding function \[ f_\theta : \mathbb {R}^D \rightarrow \mathbb {R}^d, \qquad \mbox{where} \quad d \ll D, \] that maps high-dimensional inputs (e.g., images) to low-dimensional feature vectors. These embeddings should reflect the intrinsic structure of the data: semantically similar inputs (e.g., two views of the same object) should have high similarity in the latent space, while dissimilar inputs should be mapped far apart. This geometric constraint is typically imposed using a distance metric such as cosine similarity or Euclidean distance.

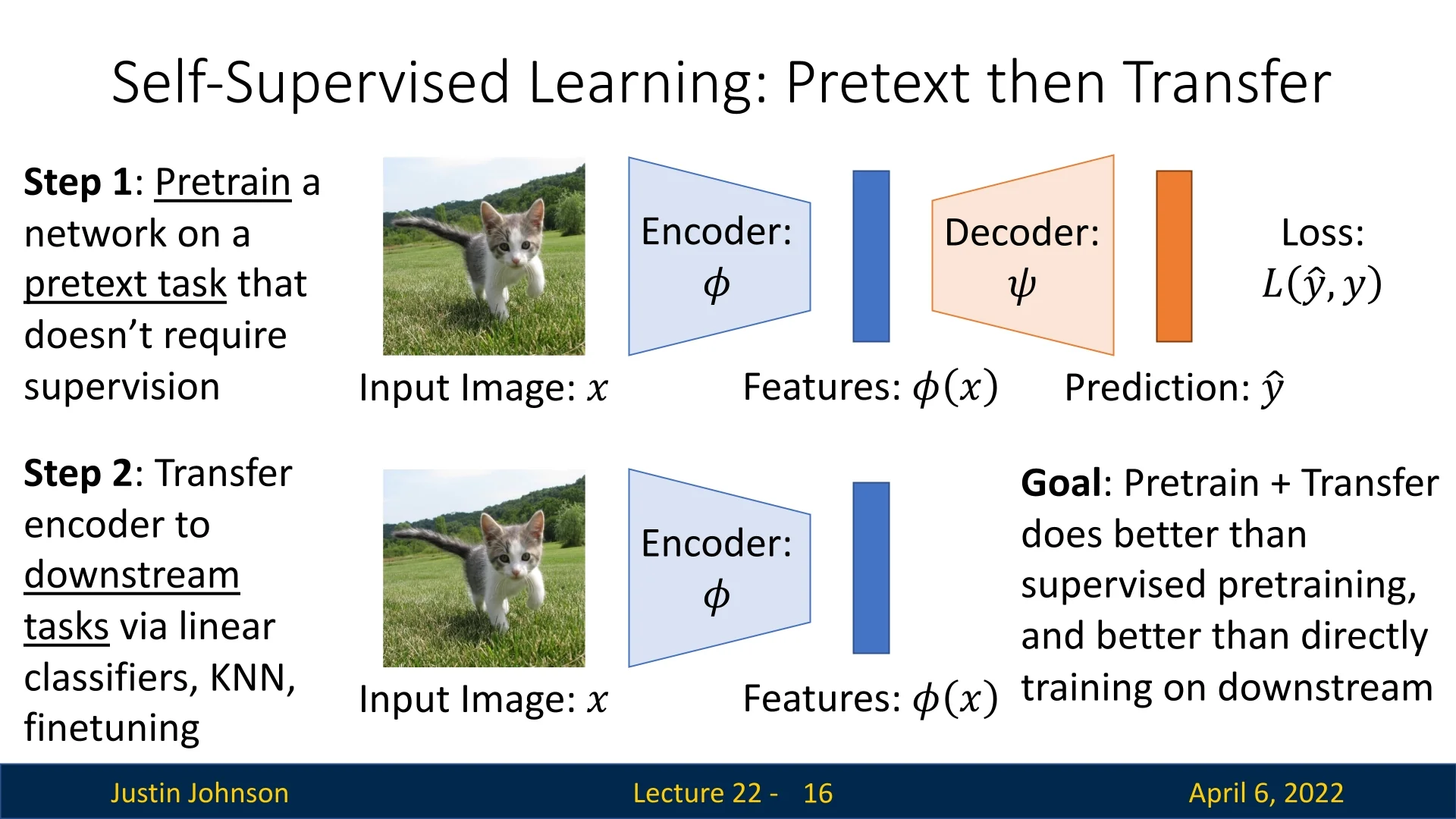

Pretraining Then Transferring Most SSL pipelines follow a two-stage workflow:

- 1.

- Pretraining: The model is trained from scratch to solve a synthetic pretext task using only unlabeled data. This forces the encoder to develop robust, general-purpose features.

- 2.

- Transfer: The learned encoder is then adapted to a downstream task. This can be done by fine-tuning all weights using a small amount of labeled data, or by freezing the encoder and training only a lightweight head (e.g., a linear classifier).

This two-phase approach is illustrated in Figure 22.1. Notably, SSL-based pretraining can outperform both randomly initialized models and models trained in a fully supervised manner on large-scale labeled datasets such as ImageNet—especially when downstream labels are scarce.

Embedding Geometry and Semantic Similarity At the heart of SSL is the idea of embedding structure. The model is encouraged to produce similar embeddings for input samples that are semantically related (e.g., different augmentations of the same image), while enforcing dissimilarity between unrelated examples. This results in a representation space in which similarity under a fixed metric (such as cosine similarity) reflects semantic closeness. In many cases, the learned embeddings can serve directly as features for classification, retrieval, or verification.

Why Pretext Tasks Work Although pretext tasks may appear synthetic or even trivial in nature, their solutions often require understanding of high-level structure and semantics. For example, a task that involves predicting the correct orientation of an image implicitly forces the model to recognize objects and their canonical alignment. Similarly, tasks that rely on partial reconstruction require capturing texture, geometry, and context. By solving such surrogate tasks, the model acquires transferable visual concepts that generalize well across datasets and tasks.

Categories of Pretext Tasks Pretext tasks vary in their construction, but all share the goal of inducing the model to learn informative and transferable features. They can be grouped into several broad categories:

-

Generative tasks: These involve reconstructing or generating parts of the input image:

- Autoencoding: Compress and reconstruct the original image.

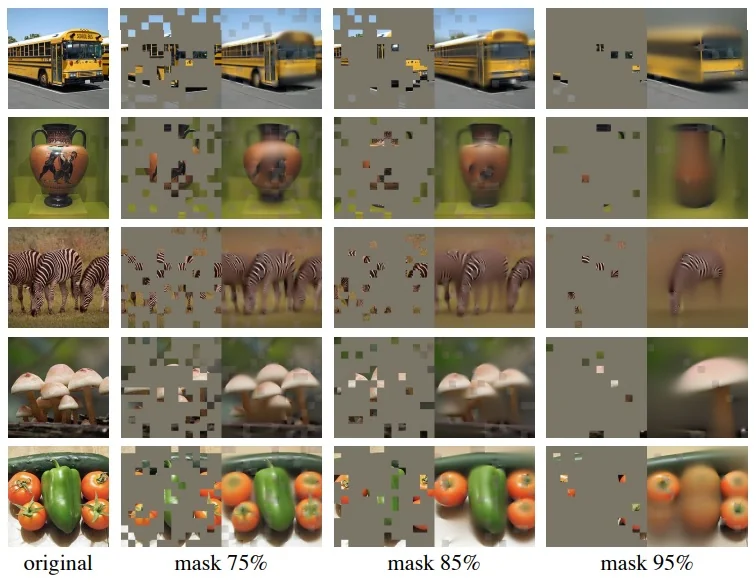

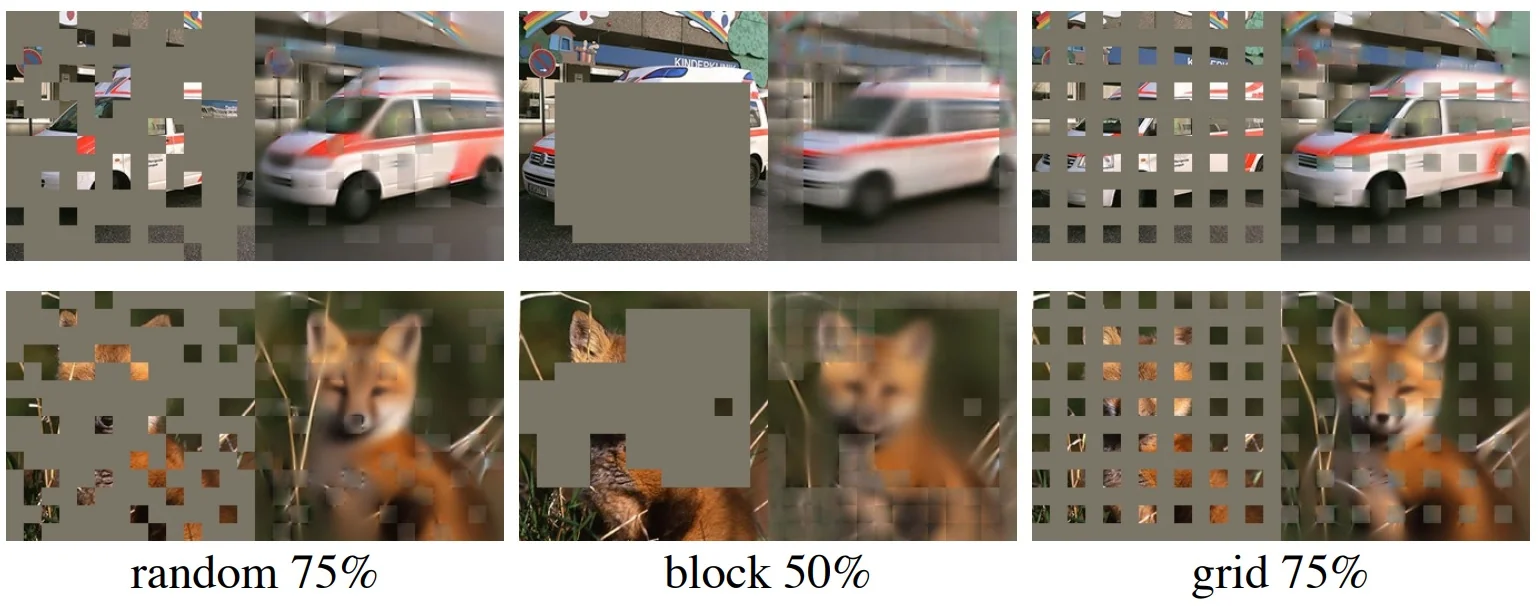

- Denoising / Masked Modeling [210]: Predict masked or corrupted image regions.

- Colorization [777]: Recover color from grayscale inputs.

- Inpainting [472]: Fill in missing patches.

- Autoregressive prediction: Predict future pixels or patches based on context.

- Generative Adversarial Training [180]: Learn to synthesize realistic images.

-

Discriminative tasks: These involve predicting a categorical property or relation:

- Context prediction [129]: Identify the relative spatial layout of image patches.

- Rotation prediction [172]: Classify the discrete rotation applied to an image.

- Clustering and pseudo-labeling [70]: Assign images to unsupervised feature clusters.

- Similarity discrimination [88, 211]: Distinguish between similar and dissimilar inputs.

-

Multimodal tasks: These extend SSL beyond RGB by incorporating other input modalities:

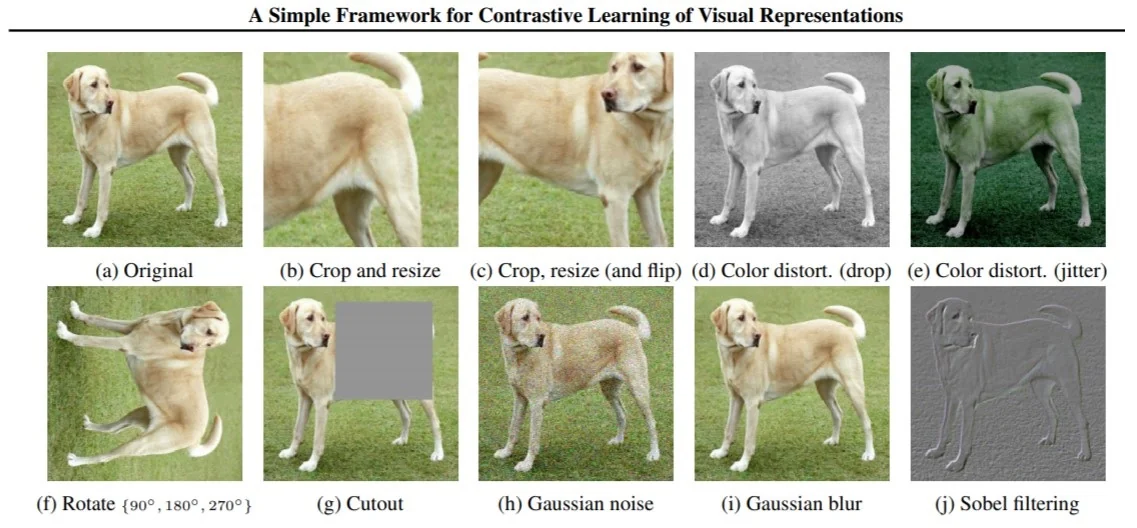

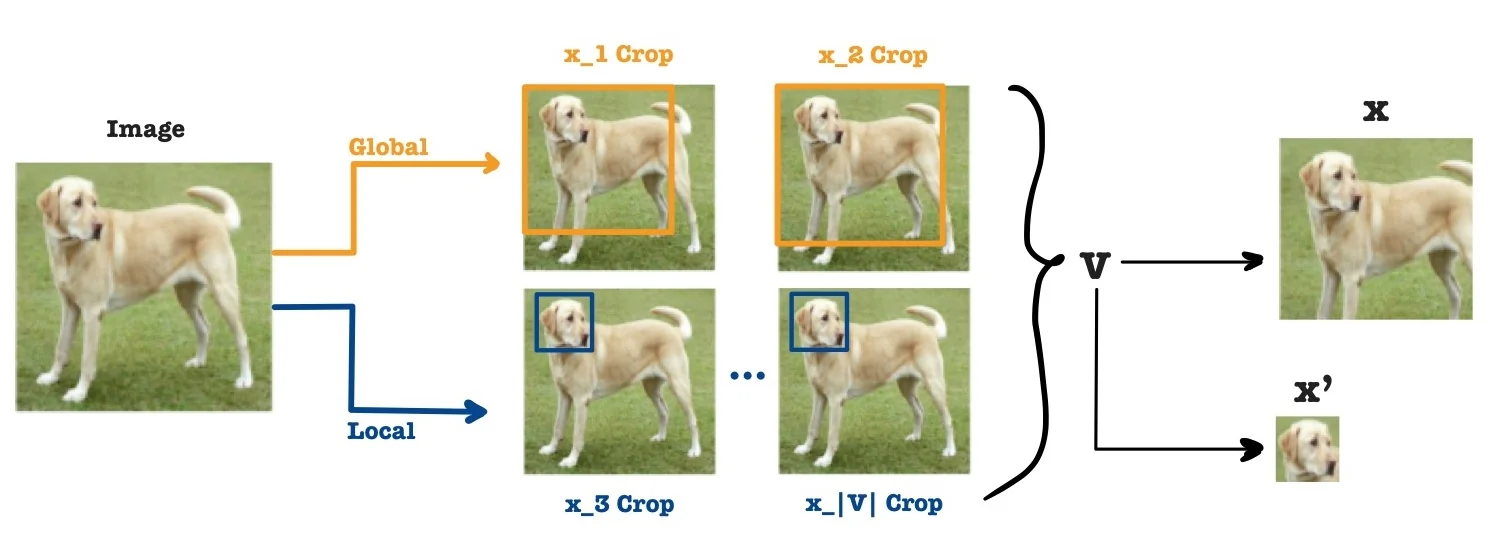

Backbones, Augmentations, and Losses The success of SSL depends not only on the task formulation but also on architectural and algorithmic choices. Backbone networks such as ResNets [206] and Vision Transformers [133] are commonly used to extract hierarchical features. Data augmentations—such as cropping, flipping, color jittering, and blurring—play a critical role in enforcing invariance and robustness by creating diverse input views. Loss objectives vary by task type and are tailored to align representations appropriately; further details are introduced later in this chapter.

Summary Self-supervised learning enables models to learn visual representations by solving data-derived pretext tasks. These representations, encoded as compact embeddings, exhibit semantic structure and generalize across tasks and domains. SSL has emerged as a foundational paradigm for scalable learning in the absence of labels.

22.1.2 Why Self-Supervised Learning?

Supervised Learning is Expensive Modern deep learning systems thrive on data—but high-quality labeled datasets are costly to obtain at scale. Consider the task of labeling one billion images: even under optimistic assumptions (10 seconds per image, a wage of $15/hour), the annotation cost exceeds $40 million. This estimate excludes setup overheads, platform fees, and quality control, meaning real-world costs could easily be two to three times higher. As models grow larger and more data-hungry—such as Vision Transformers and foundation models—this dependency on human-annotated supervision becomes increasingly impractical.

But Unlabeled Data is Free (and Plentiful) In contrast, unlabeled image data is ubiquitous. Vast corpora of raw images can be harvested from the web, videos, or embedded sensors at minimal cost. Self-Supervised Learning (SSL) capitalizes on this abundance by creating artificial supervision signals from the data itself. Rather than relying on manually assigned class labels, SSL constructs pretext tasks—auxiliary objectives that encourage the model to uncover meaningful structures within the input.

Learning Like Humans Unlike traditional supervised systems, human learning is largely unsupervised. Babies are not handed millions of labeled examples—instead, they learn by interacting with their environment, forming expectations, and detecting patterns. SSL adopts a similar philosophy: it trains models to predict naturally occurring signals in the input (e.g., spatial context, color, motion, or other parts of the image), enabling them to develop internal representations that generalize across tasks.

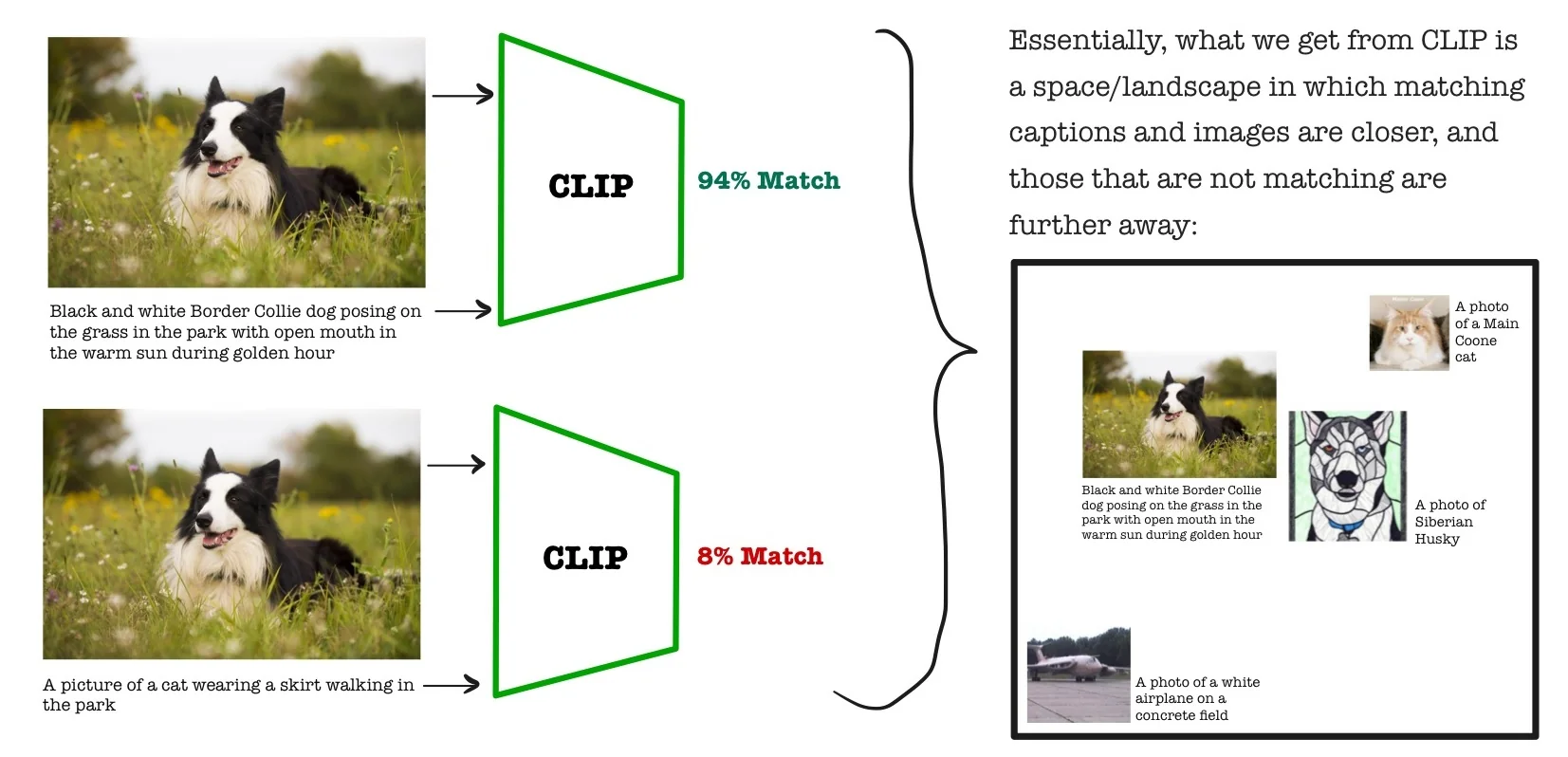

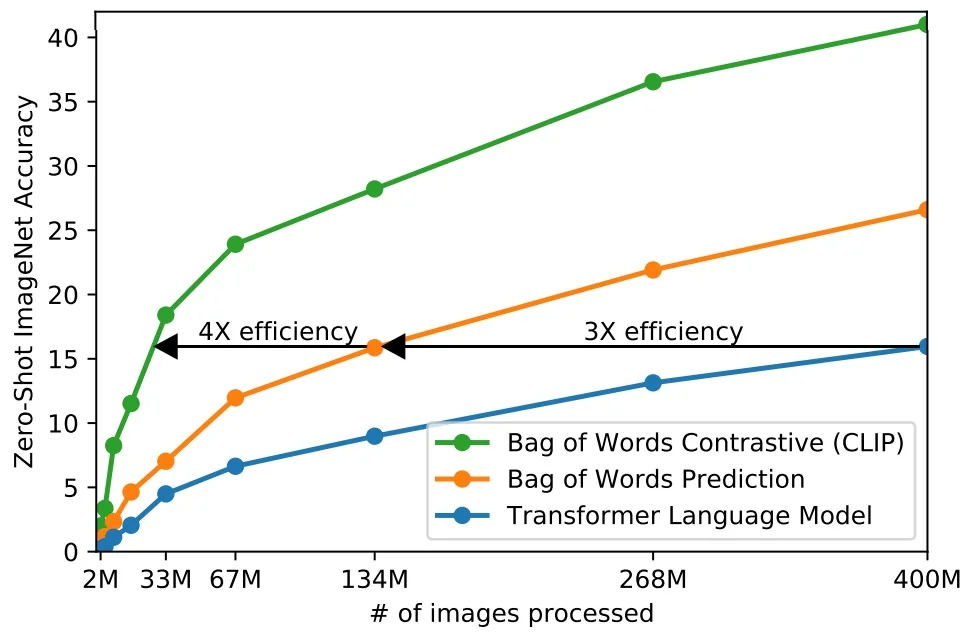

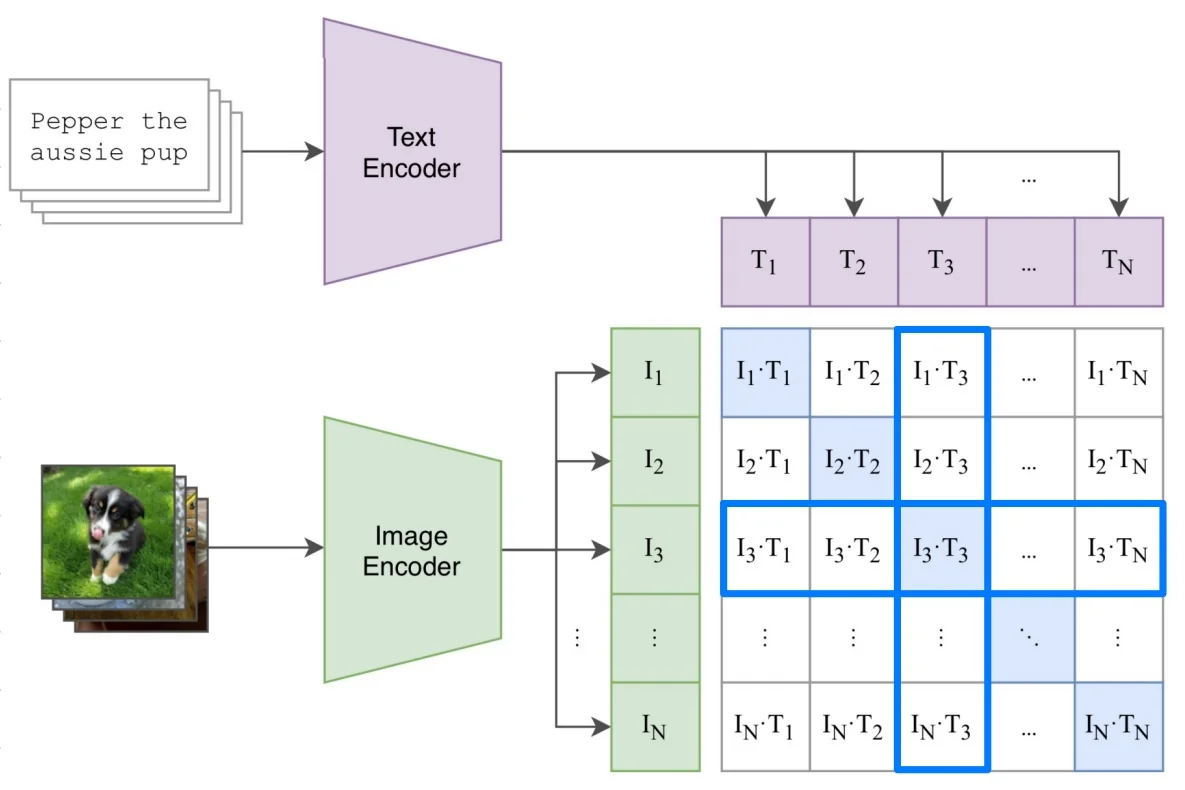

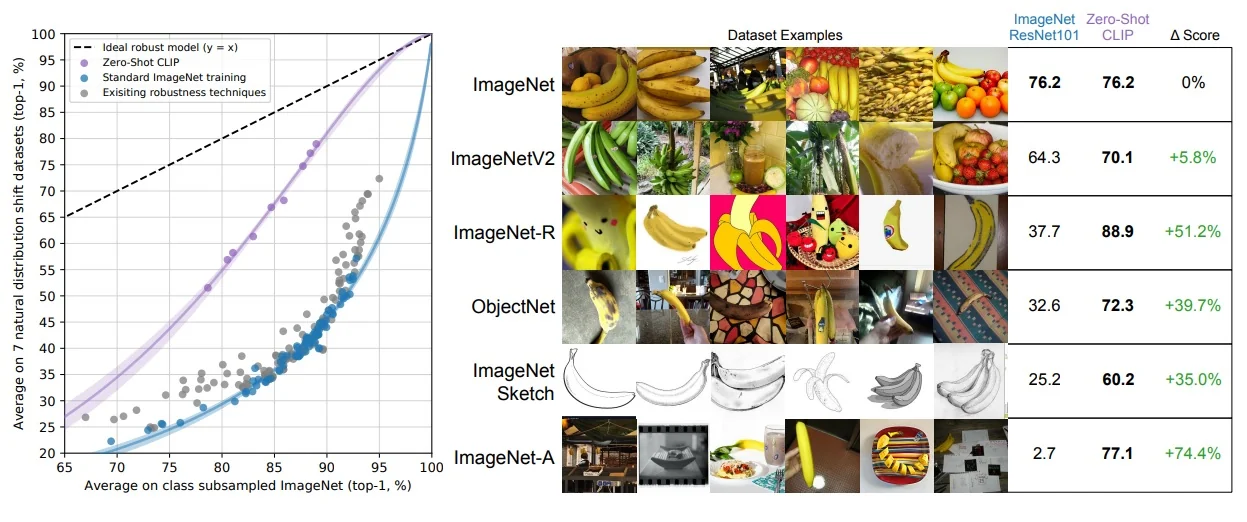

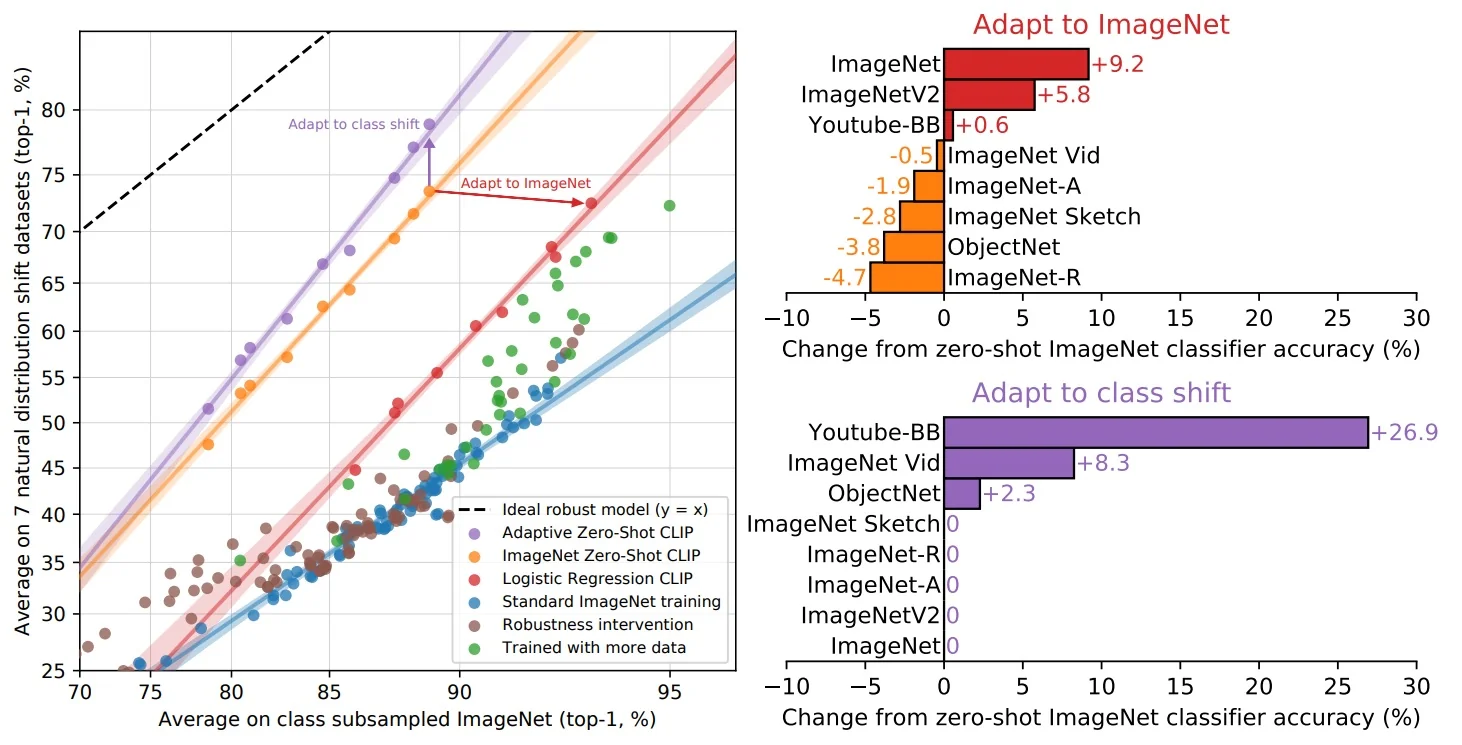

SSL as the Backbone of Foundation Models This learning paradigm has enabled the emergence of powerful generalist systems, such as foundation models in vision and language. For example, CLIP [498] learns visual representations by aligning images with their associated captions—without requiring fine-grained category labels. Inspired by the success of large-scale self-supervised pretraining in NLP (e.g., GPT [59]), these models rely on SSL objectives—such as contrastive learning, masked prediction, or multimodal alignment—to learn semantically rich, transferable features. As a result, SSL is now a key pillar in scaling visual learning beyond the limits of supervision.

22.1.3 LeCun’s AI Cake: SSL as the Base Layer

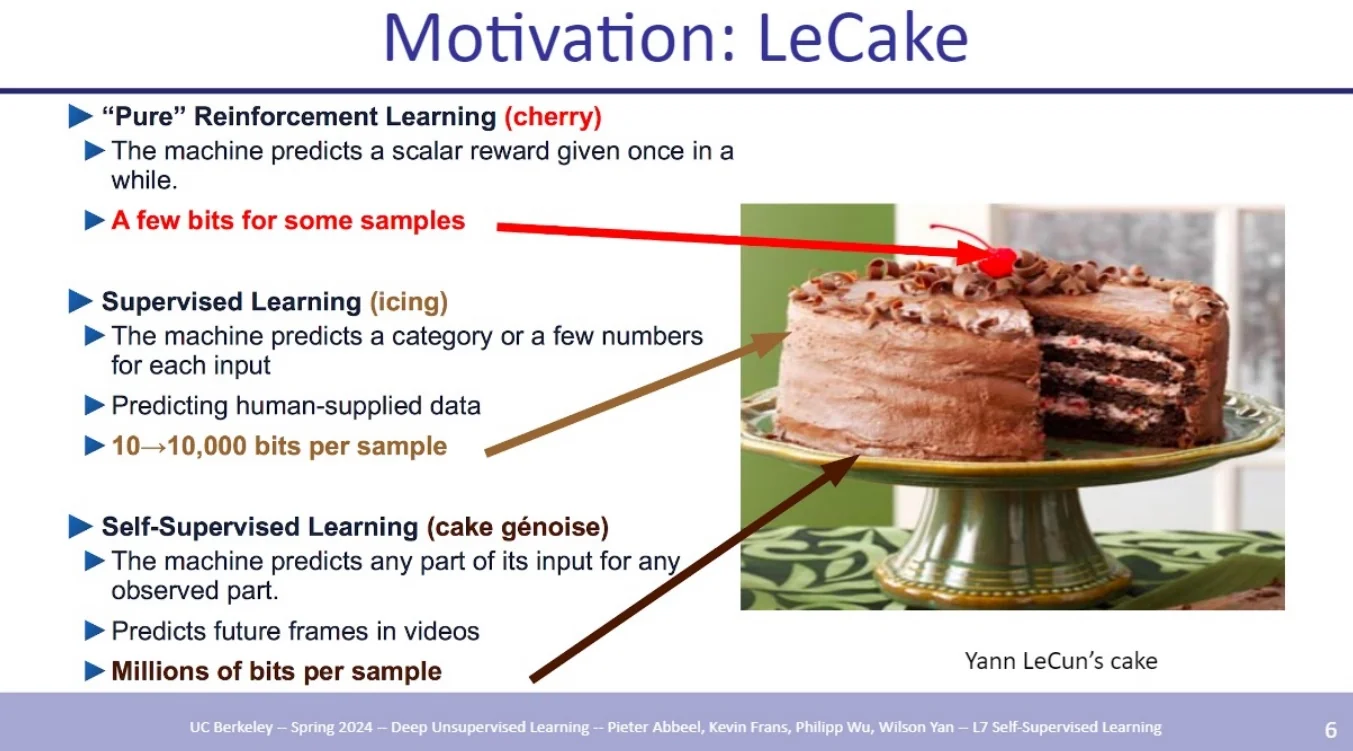

The Cake Analogy Yann LeCun famously likened the components of AI to a layered cake:

- Génoise (Base): Self-Supervised Learning—general representation learning from unlabeled data.

- Icing: Supervised Learning—fine-tuning on specific tasks with labeled data.

- Cherry: Reinforcement Learning—learning from sparse reward signals in sequential decision tasks.

Practical Significance This analogy underscores that any intelligent pipeline should begin with SSL to form robust foundational knowledge before adding task-specific or behavior-based learning.

22.1.4 Practical Integration into Deep Learning Pipelines

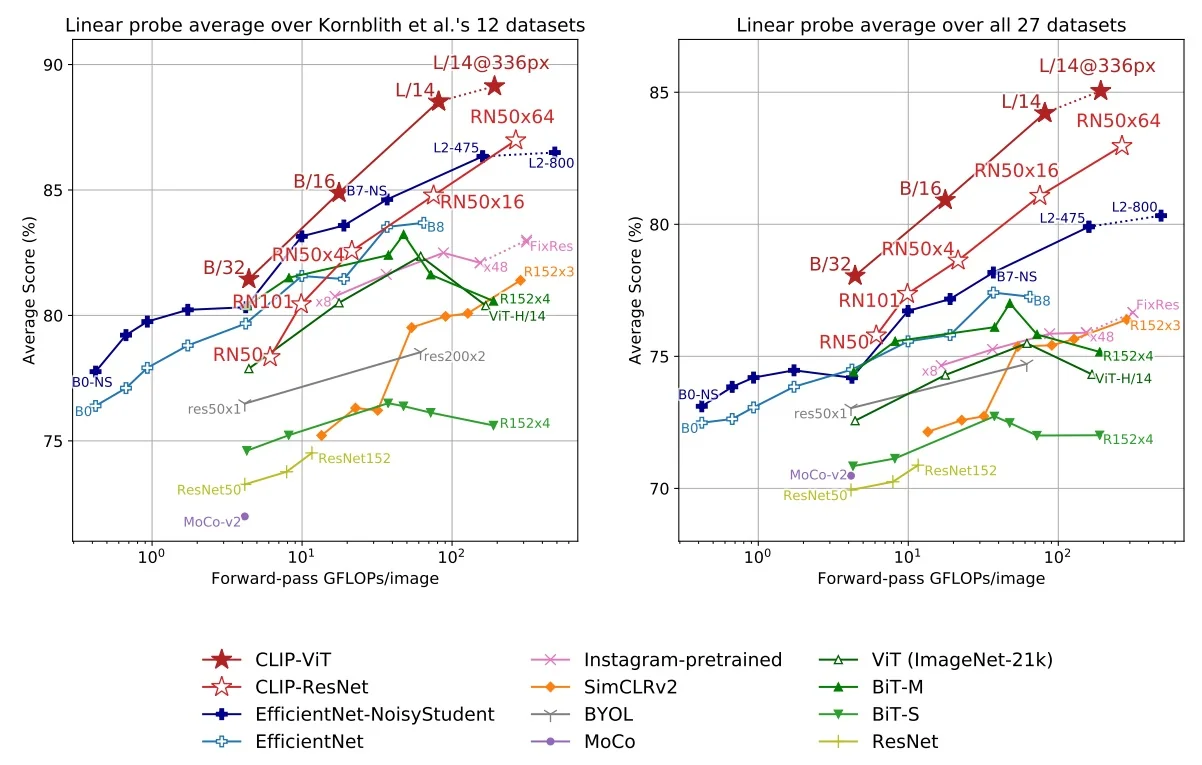

How SSL is Used in Practice SSL models are often trained on vast unlabeled datasets to produce strong feature extractors. These are then reused in downstream tasks:

- Linear classifiers for probing representation quality.

- KNN retrieval to test neighborhood consistency.

- MLPs for non-linear transfer to downstream tasks.

- Fine-tuning the backbone network on task-specific data.

Flexible Transfer and Modularity In practice, a lightweight classifier—typically a linear layer or a shallow multilayer perceptron (MLP)—is attached on top of the frozen encoder to perform downstream tasks. If the learned representations are not perfectly linearly separable, using an MLP head with 2–3 layers often yields substantial performance improvements by capturing mild nonlinearities.

Full fine-tuning of the encoder is also possible and sometimes beneficial when ample downstream labels are available. However, this approach introduces significantly more trainable parameters and risks overfitting in low-data regimes. As such, full fine-tuning should be reserved for downstream datasets of moderate to large scale, while smaller datasets benefit more from frozen representations with minimal adaptation.

Strategic Impact and Adoption Self-supervised learning has become the default pretraining strategy for modern vision models, particularly large-scale architectures like Vision Transformers. By eliminating the need for manual annotation, SSL shifts the bottleneck from label curation to scalable data collection, enabling broader and more cost-effective deployment. Its ability to learn transferable features from unlabeled data makes it a foundational component of contemporary AI pipelines.

22.2 A Taxonomy of Self-Supervised Representation Learning Methods

Self-Supervised Representation Learning (SSRL) now comprises a diverse set of methods that extract meaningful representations from unlabeled data. These methods are generally categorized into four principal families based on their core learning strategies.

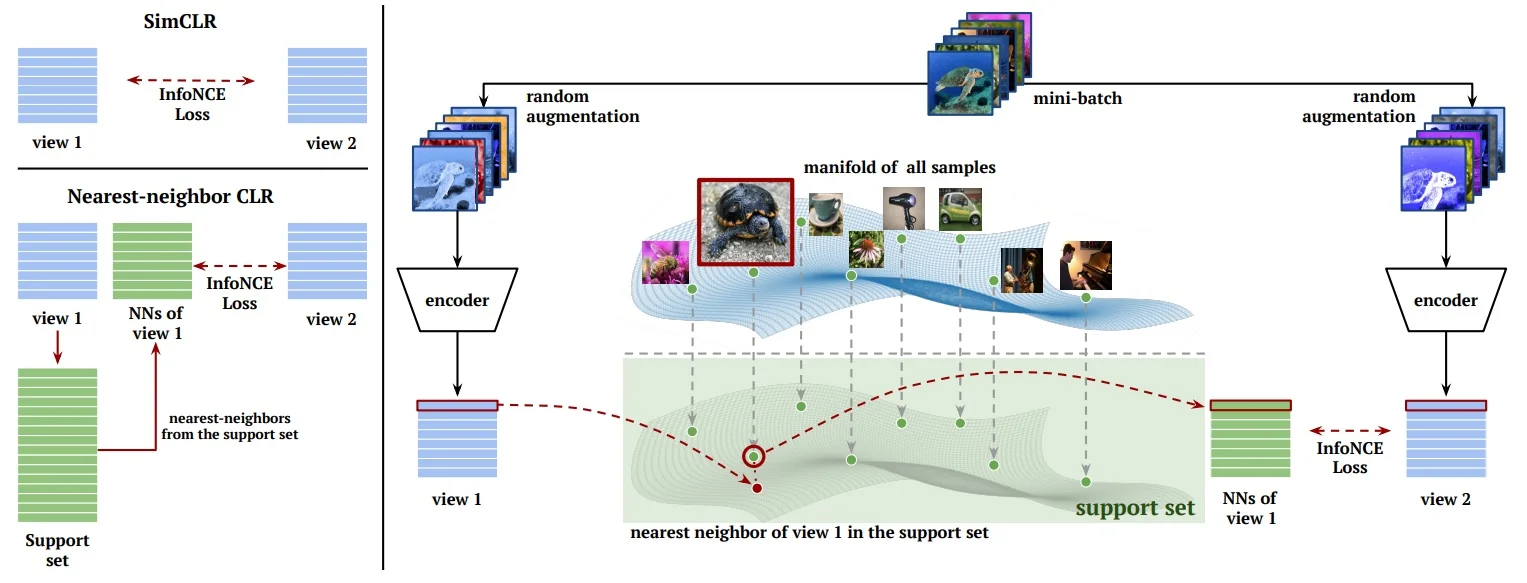

22.2.1 Contrastive Methods

Discriminative Representations via Similarity and Dissimilarity Contrastive approaches train encoders to pull together representations of similar samples (positive pairs) and push apart those of dissimilar ones (negative pairs). These typically rely on aggressive data augmentation and clever mining or sampling strategies.

- SimCLR / SimCLR v2 [88, 89]: Frameworks that rely on strong augmentations and a projection head; SimCLR v2 adds depth and fine-tuning.

- MoCo / MoCo v2 / MoCo v3 [211, 95, 94]: Momentum Contrast methods with a dynamic dictionary and momentum encoder; v2 improves augmentations and projection design, v3 applies them to ViTs.

- ReLIC / ReLIC v2 [437, 620]: Contrastive methods that extend instance discrimination with latent clusters.

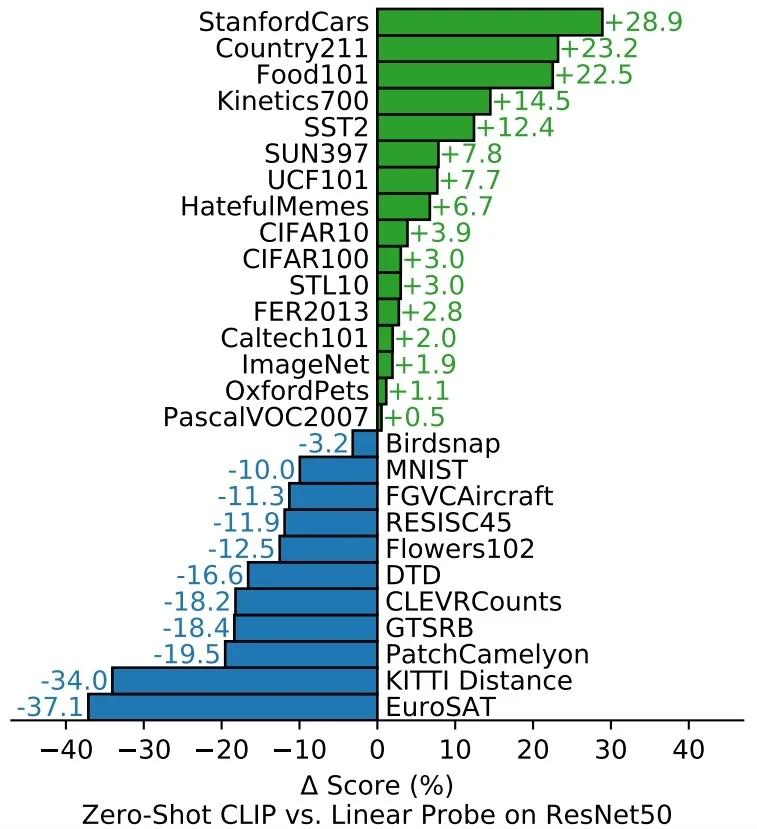

- CLIP [498]: Multimodal contrastive learning aligning image and text embeddings.

- NNCLR [138]: Nearest-neighbor based contrastive learning for representation smoothing and consistency.

Insight Contrastive methods achieve strong performance but often require large batch sizes, memory banks, or additional sampling heuristics to mine hard negatives.

22.2.2 Distillation-Based Methods

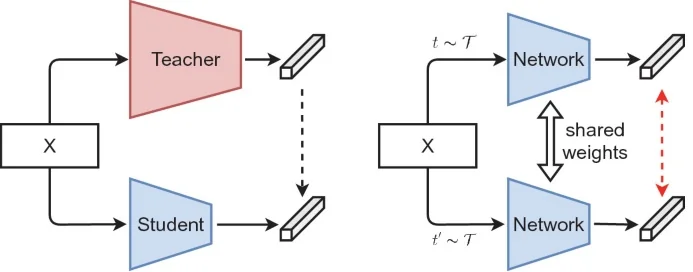

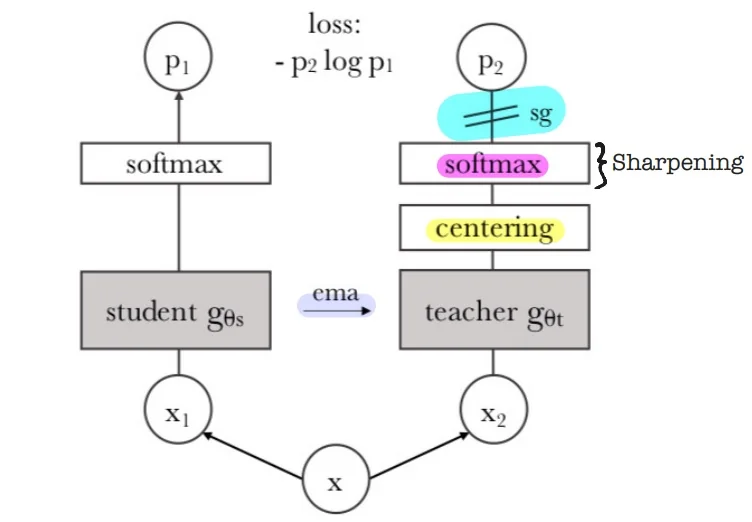

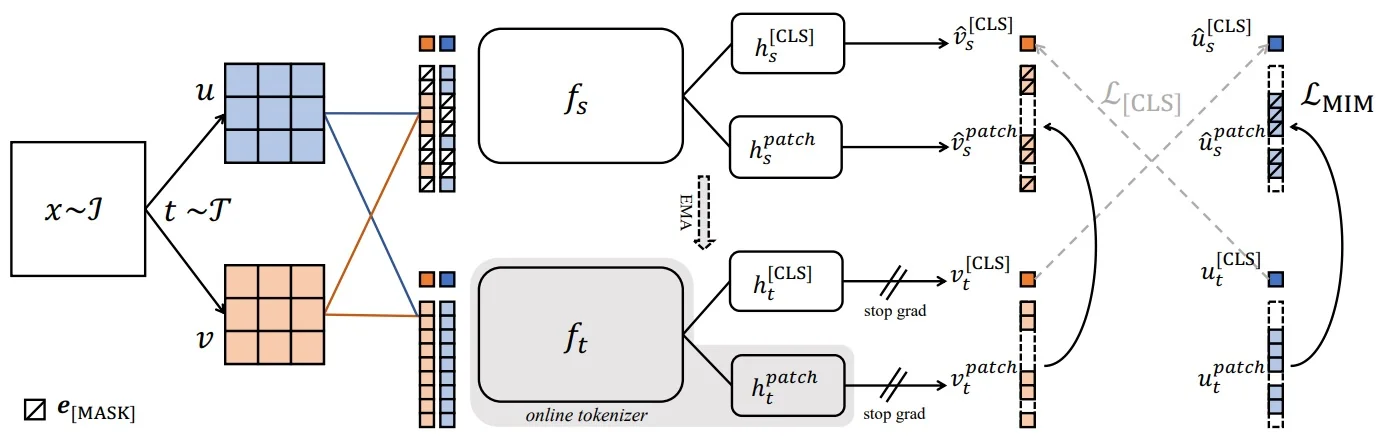

Teacher-Student Framework without Negatives Distillation-based approaches avoid negative samples by training a student network to match the embeddings or output distributions of a slowly-updated teacher model.

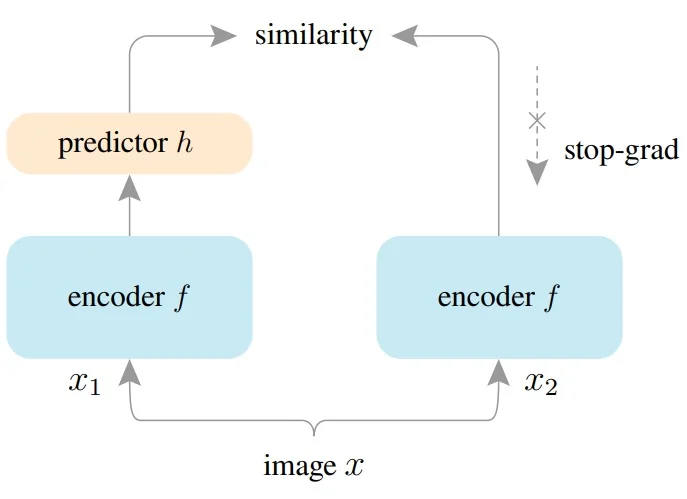

- BYOL [188]: Learns representations by aligning student and teacher networks without any contrastive negatives.

- SimSiam [92]: Demonstrates that negative samples and momentum encoders are not strictly required.

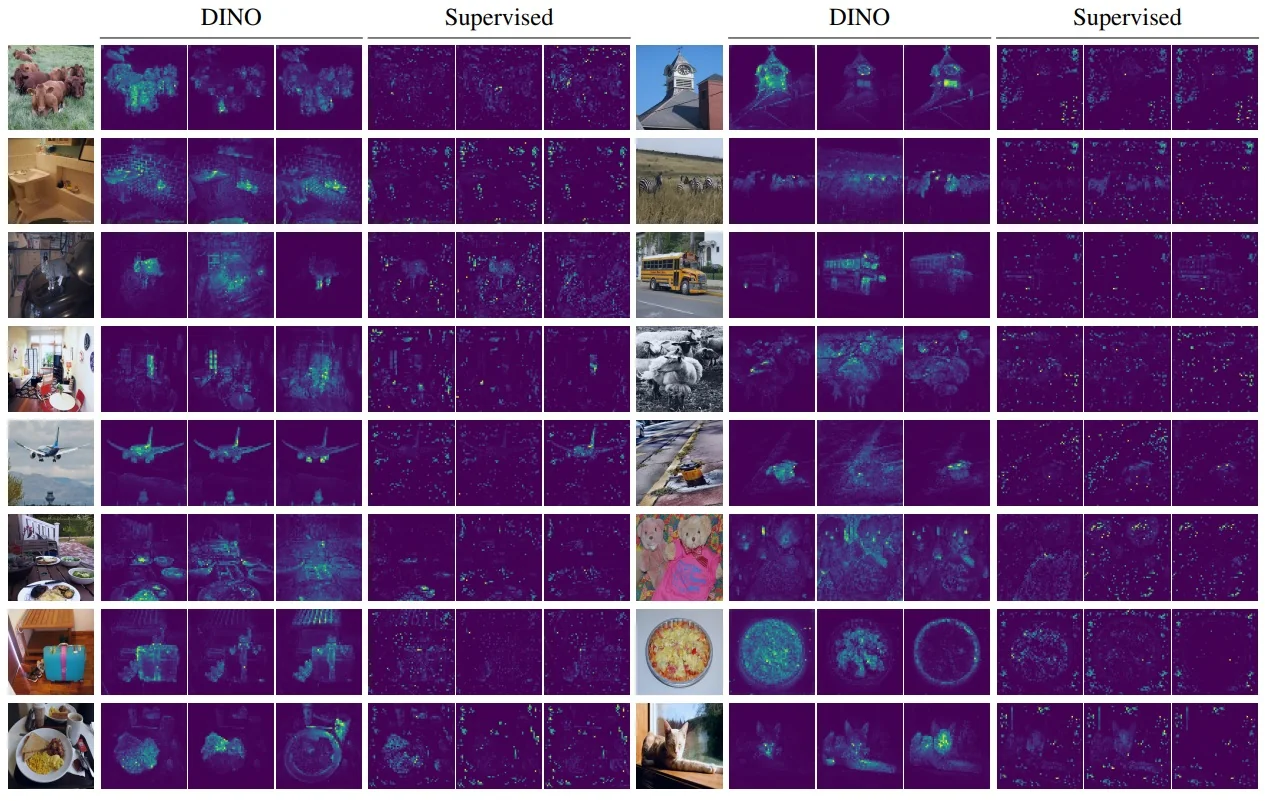

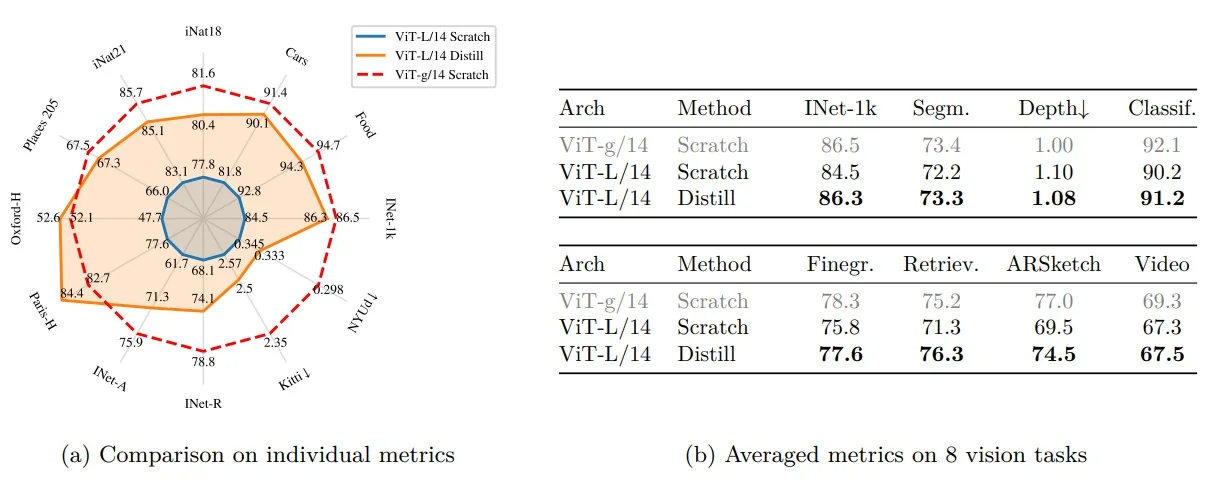

- DINO / DINOv2 [69, 463]: Combines ViT architectures with self-distillation, yielding highly transferable visual features.

- C-BYOL [319]: Introduces curriculum learning into the BYOL pipeline to improve robustness.

Insight These methods are empirically robust, especially when combined with ViT backbones, and combat representation collapse using asymmetric loss structures or architectural regularization.

22.2.3 Feature Decorrelation Methods

Promoting Redundancy Reduction These methods encourage feature dimensions to be uncorrelated, ensuring each encodes distinct information.

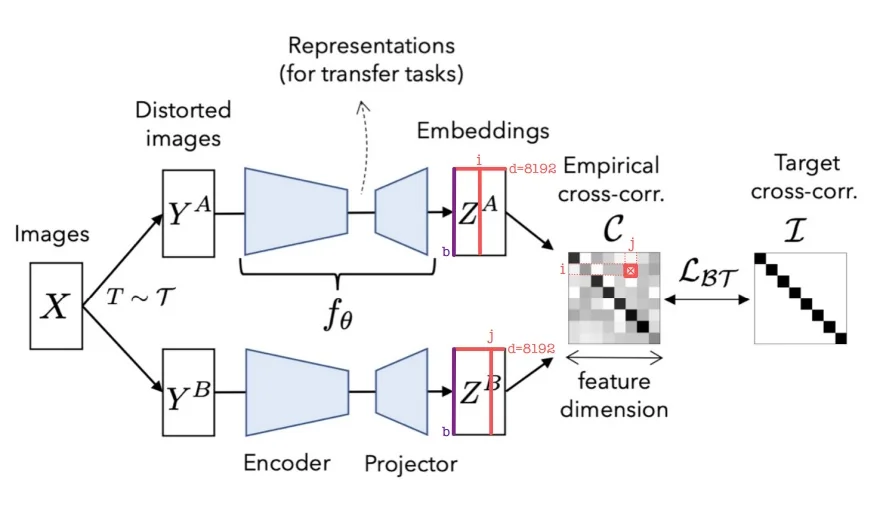

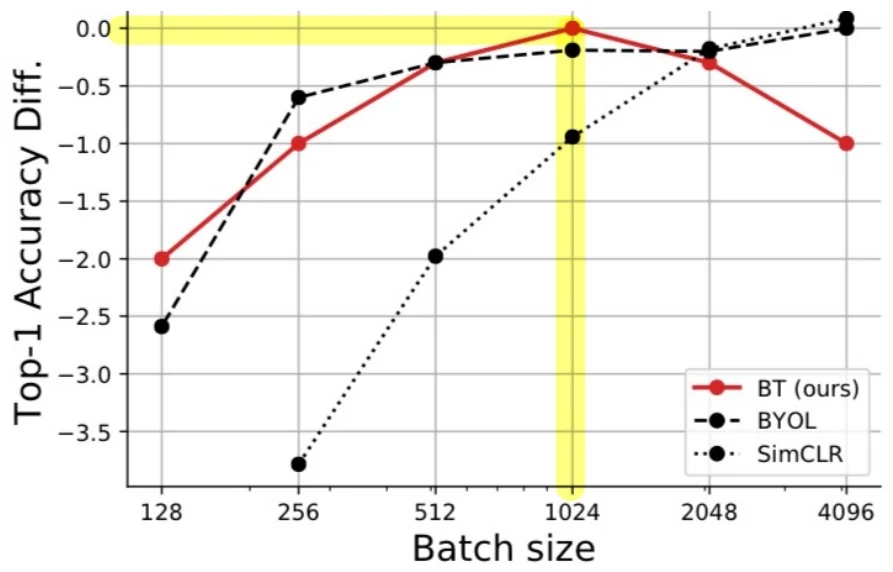

- Barlow Twins [751]: Minimizes off-diagonal cross-correlations while aligning features.

- VICReg [28]: Combines variance preservation with invariance and decorrelation terms.

- TWIST [145]: Adds whitening-based losses atop Barlow-style objectives to enhance decorrelation.

Insight By enforcing statistical independence across channels, these approaches reduce collapse risk and yield more disentangled representations.

22.2.4 Clustering-Based Methods

Learning via Group-Level Semantics Clustering-based approaches group similar samples using pseudo-labels from online or offline clustering, and then train the model to predict cluster assignments.

- DeepCluster / DeeperCluster [70, 73]: Alternate between k-means clustering and training the network using cluster assignments.

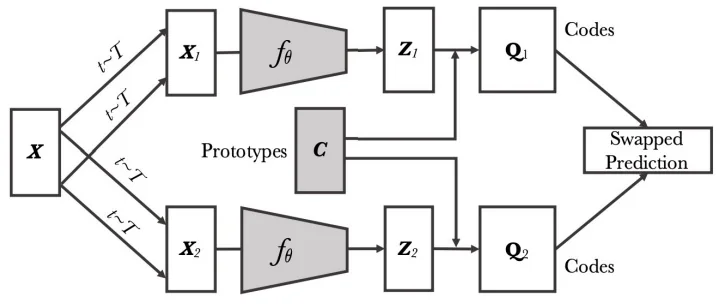

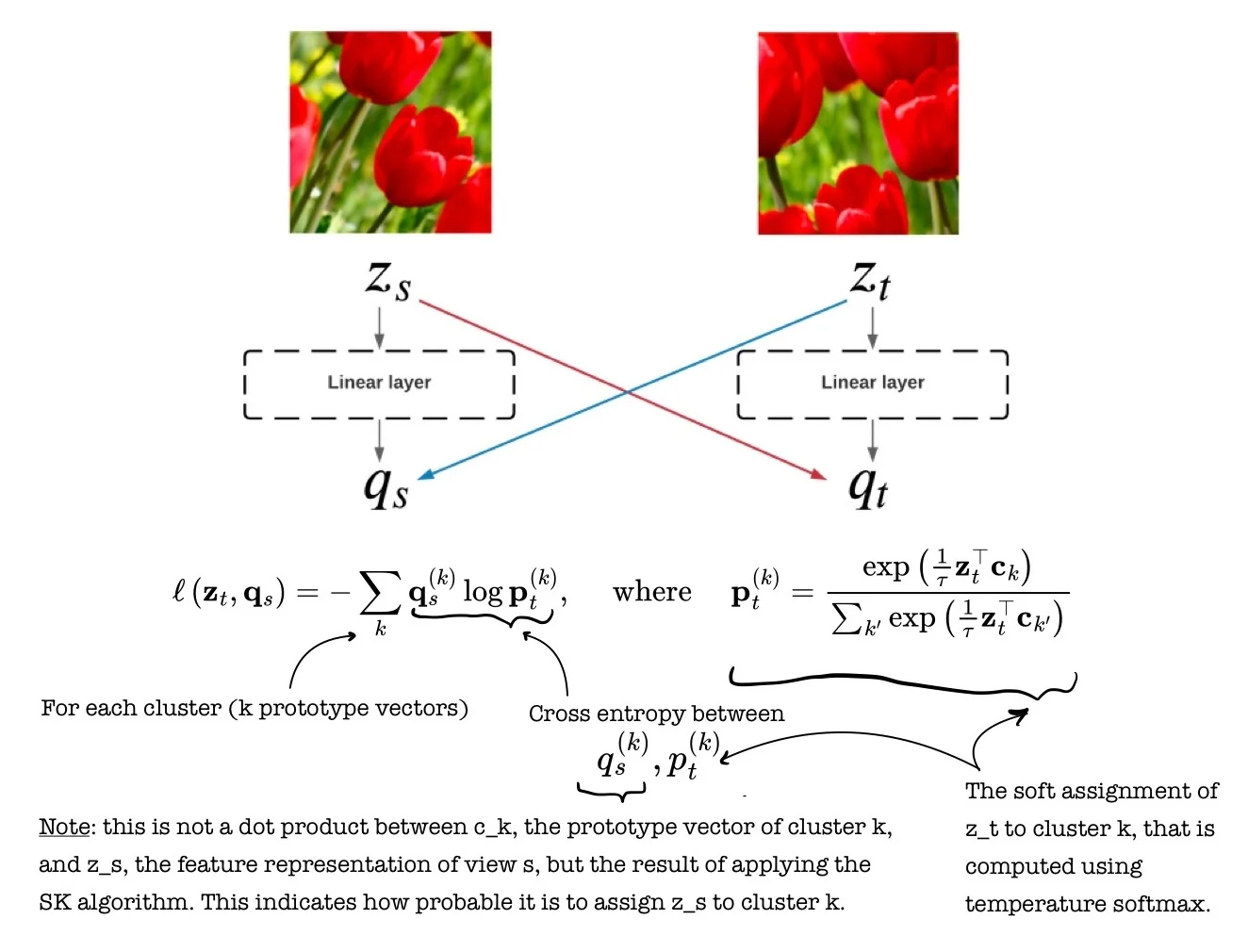

- SwAV [72]: Learns cluster prototypes and aligns augmentations via swapped prediction.

Insight These methods bridge the gap between contrastive and generative modeling, capturing semantic structure without explicit supervision or handcrafted positives/negatives.

Summary Table

| Category | Key Mechanism | Representative Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Contrastive | Pull together similar samples; repel negatives using contrastive losses | SimCLR, MoCo, CLIP, ReLIC, ReLICv2, NNCLR |

| Distillation | Match teacher and student outputs via EMA; no negatives needed | BYOL, SimSiam, DINO, DINOv2, C-BYOL |

| Feature Decorrelation | Enforce uncorrelated dimensions via covariance-based losses | Barlow Twins, VICReg, TWIST |

| Clustering | Use pseudo-labels from clustering to form supervision | DeepCluster, SwAV, DeeperCluster |

22.3 Contrastive Methods

22.3.1 Motivation for Contrastive Learning

Among various SSL strategies, contrastive learning has emerged as a particularly effective and conceptually elegant approach for acquiring rich and transferable visual representations.

A central objective in SSL is to train a model that maps high-dimensional data (e.g., images in \( \mathbb {R}^D \)) into compact, semantically meaningful embeddings in a lower-dimensional space \( \mathbb {R}^d \), where \( d \ll D \). These embeddings are intended to satisfy a key geometric property: inputs that are semantically similar should have representations that are close under a chosen similarity metric (typically cosine similarity), while dissimilar inputs should be mapped far apart. Such semantic alignment in the embedding space enables generalization across a wide range of downstream tasks, including classification, retrieval, and segmentation.

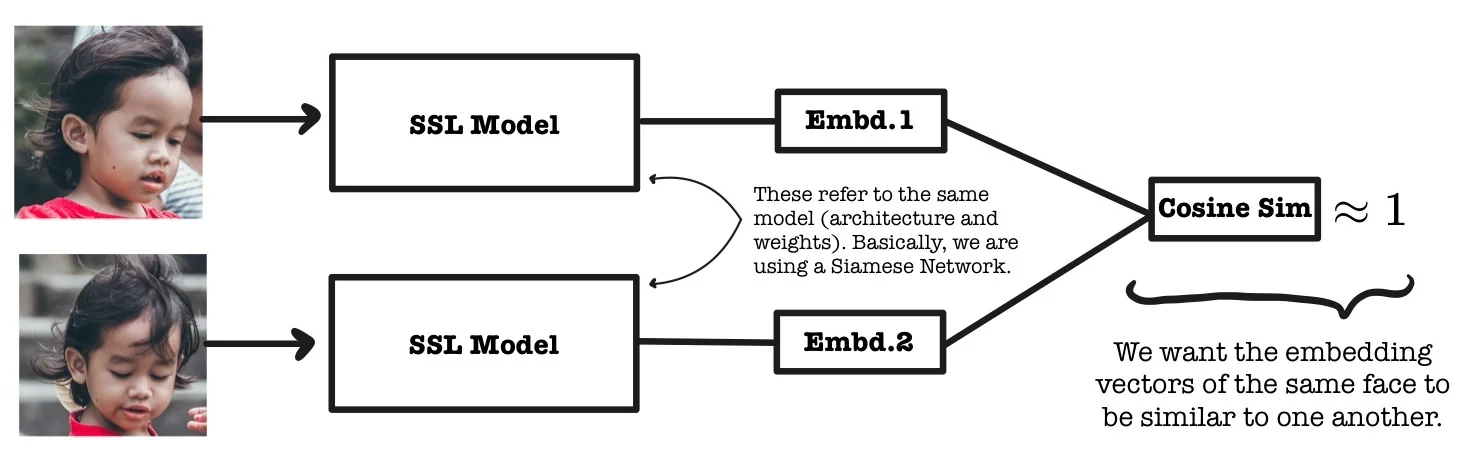

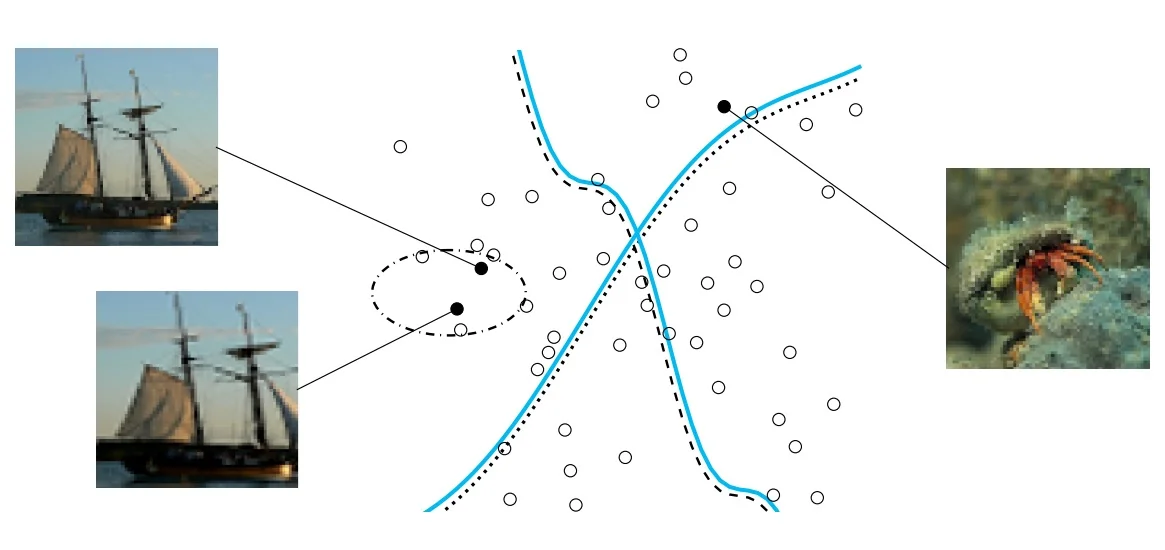

Core Idea Contrastive learning formalizes representation learning as a discrimination problem in the latent space. The model is trained using positive pairs—typically two different augmentations of the same image—and negative pairs, composed of unrelated images. The objective is to pull positive pairs close together in the embedding space while pushing negative pairs apart. This dynamic creates a structured feature space where semantic similarity correlates with geometric proximity.

A widely used formulation is based on the contrastive loss, such as InfoNCE [459], which minimizes the distance between an anchor and its positive key, while simultaneously maximizing the distance to negative keys in a batch or memory bank. Mathematically, for an anchor representation \( z_i \) and its positive counterpart \( z_j \), the loss takes the form: \[ \mathcal {L}_{\mbox{InfoNCE}} = -\log \frac {\exp (\mbox{sim}(z_i, z_j)/\tau )}{\sum _{k=1}^{K} \exp (\mbox{sim}(z_i, z_k)/\tau )}, \] where \( \mbox{sim}(\cdot , \cdot ) \) denotes cosine similarity and \( \tau \) is a temperature hyperparameter.

Instance Discrimination as a Pretext Task Unlike traditional classification, contrastive learning does not assume predefined categories. Instead, it adopts the instance discrimination paradigm, treating each image as its own class. The model learns to identify an augmented view of the same instance among a set of distractors. This formulation naturally addresses the representation collapse problem—where a model maps all inputs to the same point—by requiring the network to maintain distinctiveness across a large set of negatives.

For instance, we can decide that given a batch of \( N \) images, each image is augmented twice to produce \( 2N \) views. These are embedded via an encoder and normalized into unit vectors. The resulting \( 2N \) representations define \( N \) positive pairs and \( 2(N-1) \) negatives per anchor. Contrastive loss is then applied over these structured pairs to enforce the desired geometry of the representation space.

Avoiding Trivial Solutions One of the key advantages of contrastive learning over earlier heuristic pretext tasks (e.g., jigsaw puzzles, rotation prediction, or colorization) is its robustness to degenerate solutions. Pretext tasks based on fixed prediction targets often result in overly task-specific or low-level features. In contrast, contrastive methods build representations through relational signals—similarity between instances—thereby capturing high-level invariances and semantic content. The explicit use of negatives ensures that the encoder cannot collapse all embeddings into a trivial constant vector.

Scalability and Generalization Contrastive methods scale effectively to large datasets and can leverage high-capacity models, such as ResNet or Vision Transformers (ViTs), to learn expressive features. Large batch sizes or memory banks are often used to provide a diverse pool of negatives, although variants have also been developed to operate efficiently under smaller memory or compute budgets.

The learned representations exhibit strong transferability and often rival or surpass those obtained through supervised pretraining. Notable examples include:

- Face verification [554], where contrastive loss enables identity-preserving embeddings for recognition and clustering.

- Zero-shot classification with CLIP [498], which learns aligned embeddings for images and natural language descriptions via contrastive training, unlocking powerful cross-modal generalization.

- General-purpose pretraining, where contrastive methods such as SimCLR [88] and MoCo [211] have closed the performance gap between supervised and self-supervised approaches across many vision benchmarks.

Key Advantages The popularity of contrastive learning stems from several practical and conceptual strengths:

- State-of-the-art performance: When trained with sufficient compute and data, contrastive models achieve competitive results across a wide range of tasks.

- Transferability: Representations learned through contrastive objectives generalize well to tasks unseen during training, even with minimal fine-tuning.

- Conceptual simplicity: The framework is based on intuitive geometric principles—pull similar things together, push dissimilar things apart—and often implemented with simple Siamese or triplet architectures.

- Scalability: Contrastive methods make efficient use of large unlabeled datasets and are well-suited for modern distributed training environments.

From Semantic Similarity to Objective Formulation The core objective of contrastive learning is closely aligned with the goals of metric learning: to construct an embedding space in which semantically similar inputs are mapped to nearby vectors, and dissimilar inputs are pushed apart. Let \( f_\theta : \mathbb {R}^D \rightarrow \mathbb {R}^d \) be an encoder network that maps high-dimensional input samples \( x \in \mathbb {R}^D \) to compact feature vectors \( z = f_\theta (x) \in \mathbb {R}^d \). In practice, these embeddings are \(\ell _2\)-normalized to lie on the unit hypersphere, i.e., \( \|z\|_2 = 1 \).

A natural and widely used choice for comparing such embeddings is cosine similarity, defined as: \[ \mathrm {sim}(x_i, x_j) = \cos (\theta _{i,j}) = \frac {f_\theta (x_i)^\top f_\theta (x_j)}{\|f_\theta (x_i)\|_2 \, \|f_\theta (x_j)\|_2}. \] When embeddings are normalized, this expression simplifies to the dot product: \[ \mathrm {sim}(x_i, x_j) = f_\theta (x_i)^\top f_\theta (x_j), \] which measures the cosine of the angle \( \theta _{i,j} \) between the two vectors.

Cosine similarity ranges from \( -1 \) (opposite directions) to \( 1 \) (identical directions), with \( 0 \) indicating orthogonality. It captures the directional alignment between vectors while being invariant to their scale, making it particularly suitable for high-dimensional spaces where the absolute magnitudes of features are less meaningful than their relative orientations. In the context of contrastive learning, cosine similarity quantifies the semantic closeness of data points in the embedding space—serving as the quantitative foundation upon which the contrastive objective is built.

Contrastive Learning as Mutual Information Maximization In addition to its geometric intuition, contrastive learning can be interpreted through the lens of information theory. The goal of the model is to maximize the mutual information between two views of the same input instance—each obtained via stochastic data augmentations such as random cropping, color distortion, or blurring. These views are assumed to preserve the core semantics of the original image while introducing superficial variations.

By maximizing agreement between these positive views in the embedding space, the model learns to retain the information that is shared across augmentations. This process encourages the representation to focus on invariant, discriminative features and to discard irrelevant noise. In effect, contrastive learning approximates the maximization of mutual information between transformed views of the same input [459], guiding the model toward robust and generalizable representations.

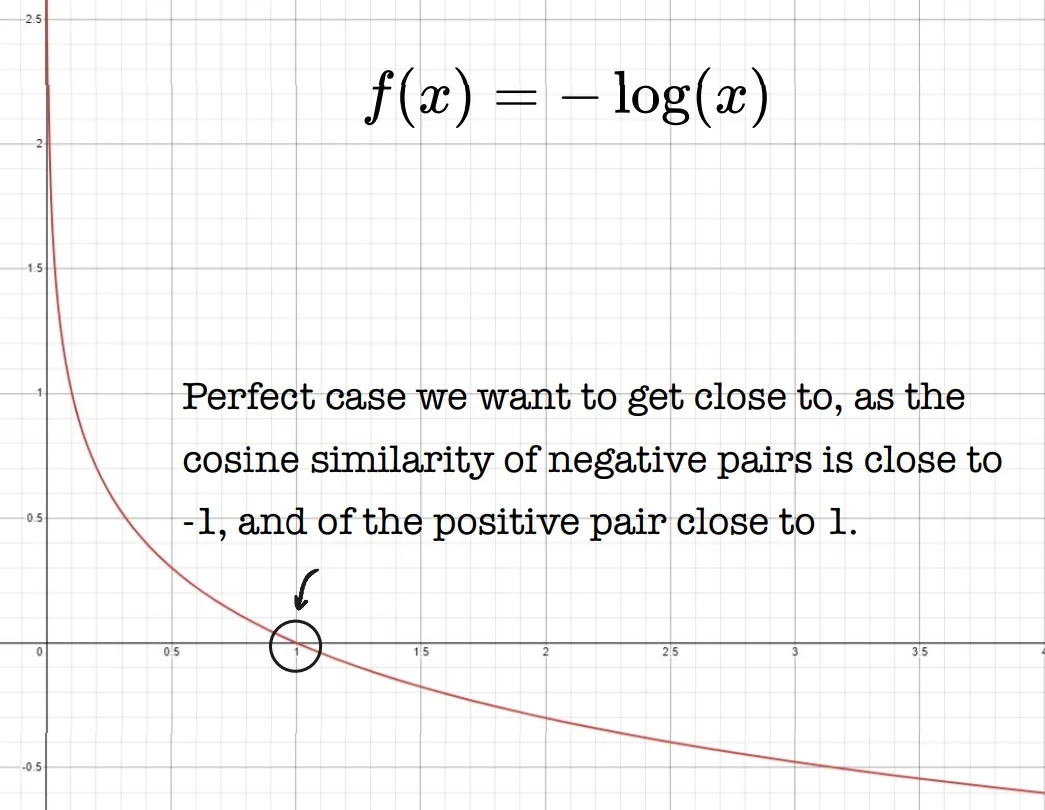

Towards a Unified Loss Function These insights—geometric alignment under cosine similarity and mutual information preservation under augmentation—together motivate a concrete learning objective. To formalize the contrastive principle, we require a loss function that:

- Encourages high similarity between embeddings of positive pairs;

- Penalizes similarity between embeddings of negative pairs.

In the next section, we derive the InfoNCE loss, a widely adopted objective that captures these goals by comparing the relative similarity of a positive pair to a set of negatives drawn from the batch or memory bank. This loss serves as the cornerstone of modern contrastive methods.

22.3.2 Origin and Intuition Behind Contrastive Loss

From Dimensionality Reduction to Discriminative Embeddings The contrastive loss was first proposed by Hadsell et al. [199] for supervised dimensionality reduction. The goal was to learn a transformation \( G_{\boldsymbol {W}}(\cdot ) \), parameterized by weights \( \boldsymbol {W} \), that maps high-dimensional inputs \( \vec {X} \in \mathbb {R}^D \) to a compact embedding space \( \mathbb {R}^d \), such that similar inputs are embedded close together and dissimilar ones are mapped at least margin \( m \) apart.

Given a pair \( (\vec {X}_1, \vec {X}_2) \) and a binary similarity label \( Y \in \{0, 1\} \), the contrastive loss is: \[ L(W, Y, \vec {X}_1, \vec {X}_2) = (1 - Y) \cdot \frac {1}{2} D_W^2 + Y \cdot \frac {1}{2} \left [\max (0, m - D_W)\right ]^2 \] where \( D_W = \| G_{\boldsymbol {W}}(\vec {X}_1) - G_{\boldsymbol {W}}(\vec {X}_2) \|_2 \).

Why the Margin Matters This loss has two regimes:

- For similar pairs (\( Y = 0 \)), the embedding distance \( D_W \) is minimized.

- For dissimilar pairs (\( Y = 1 \)), the distance is enforced to be at least \( m \).

The margin prevents the model from arbitrarily increasing dissimilar distances, akin to the hinge loss in SVMs.

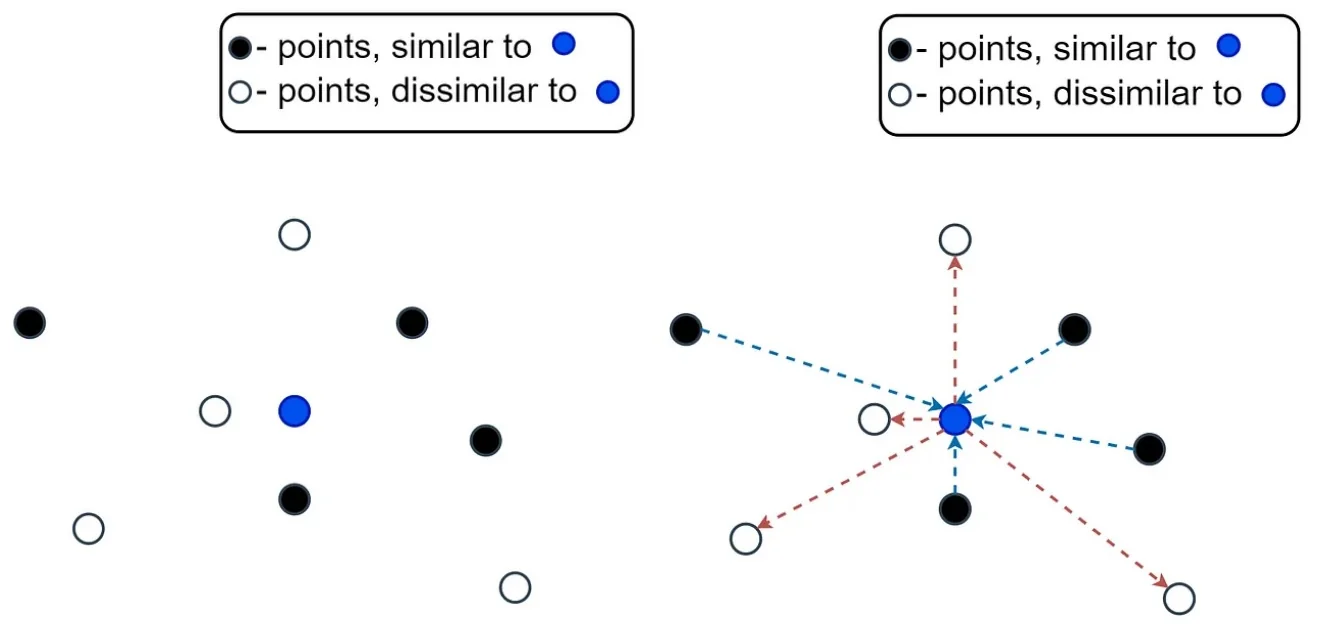

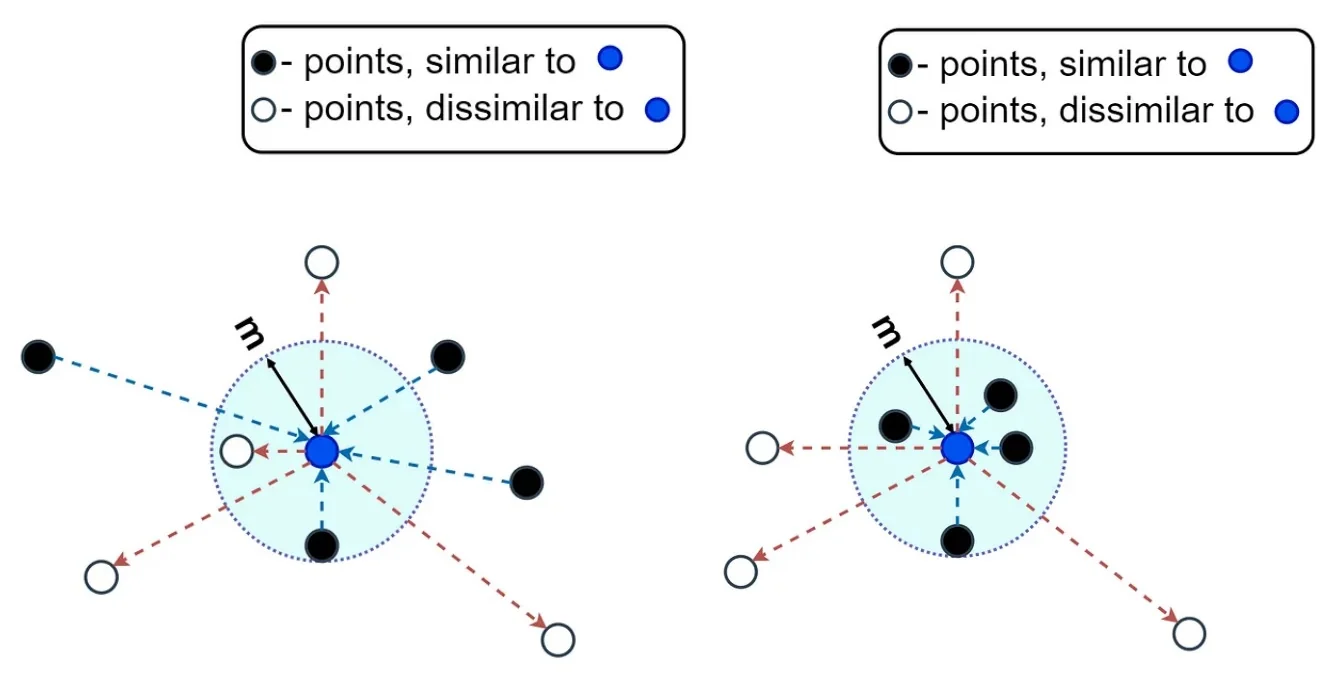

A Visual Summary of the Learning Objective The goal of contrastive learning is to shape the embedding space such that similar points are tightly clustered while dissimilar points are pushed away. This intuition is captured by minimizing the intra-class distances and maximizing the inter-class distances. Visually, we aim to shorten the intra-class arrows (from the anchor to similar samples) and lengthen the inter-class arrows (from the anchor to dissimilar samples).

Formally, for each anchor embedding \( \vec {z}_a \), we want: \[ \max _{i \in \mathcal {P}} \| \vec {z}_a - \vec {z}_i \|_2 < \min _{j \in \mathcal {N}} \| \vec {z}_a - \vec {z}_j \|_2, \] where \( \mathcal {P} \) denotes the set of similar (positive) examples and \( \mathcal {N} \) the set of dissimilar (negative) examples. This condition ensures that the most distant positive is still closer than the nearest negative—enabling accurate grouping under a simple nearest-neighbor decision rule.

This margin-based separation underpins the contrastive loss function introduced by Hadsell et al., which explicitly enforces that:

- Similar samples (label \( Y = 0 \)) fall within a small distance of the anchor;

- Dissimilar samples (label \( Y = 1 \)) are pushed outside a minimum margin \( m \).

Why Not Use \( \frac {1}{D_W} \)? One might consider directly maximizing dissimilarity by minimizing \( \frac {1}{D_W} \), where \( D_W = \| G_{\boldsymbol {W}}(\vec {X}_1) - G_{\boldsymbol {W}}(\vec {X}_2) \|_2 \). However, such a formulation is unstable: the gradient of \( \frac {1}{D_W} \) diverges as \( D_W \to 0 \), which can lead to numerical instability and overfitting. Instead, Hadsell et al.’s formulation imposes a margin-based hinge on the dissimilar term: \[ \frac {1}{2} \left [ \max (0, m - D_W) \right ]^2, \] which saturates to zero once the dissimilar pair is sufficiently separated—yielding a more stable and robust learning signal.

From Supervision to Self-Supervision Originally developed for supervised settings with labeled pairs, contrastive loss has been adapted to the self-supervised regime by removing the need for manual annotations. In this formulation, positive pairs are created by applying two different augmentations to the same image, while negative pairs are defined implicitly by treating other images in the batch (or memory bank) as dissimilar.

This strategy enables scalable training on large unlabeled datasets while learning semantically meaningful embeddings. The underlying assumption is that different augmented views of the same image share the same semantic identity.

This idea forms the basis of prominent SSL methods such as SimCLR [88], which relies on large batches and strong augmentations, and MoCo [211], which uses a momentum encoder and memory bank to maintain negative examples across iterations.

These methods extend contrastive learning to instance-level discrimination tasks without labels, preserving the core objective: pull similar samples together and push dissimilar ones apart. We now illustrate how augmented views form anchor–positive–negative triplets used in contrastive training.

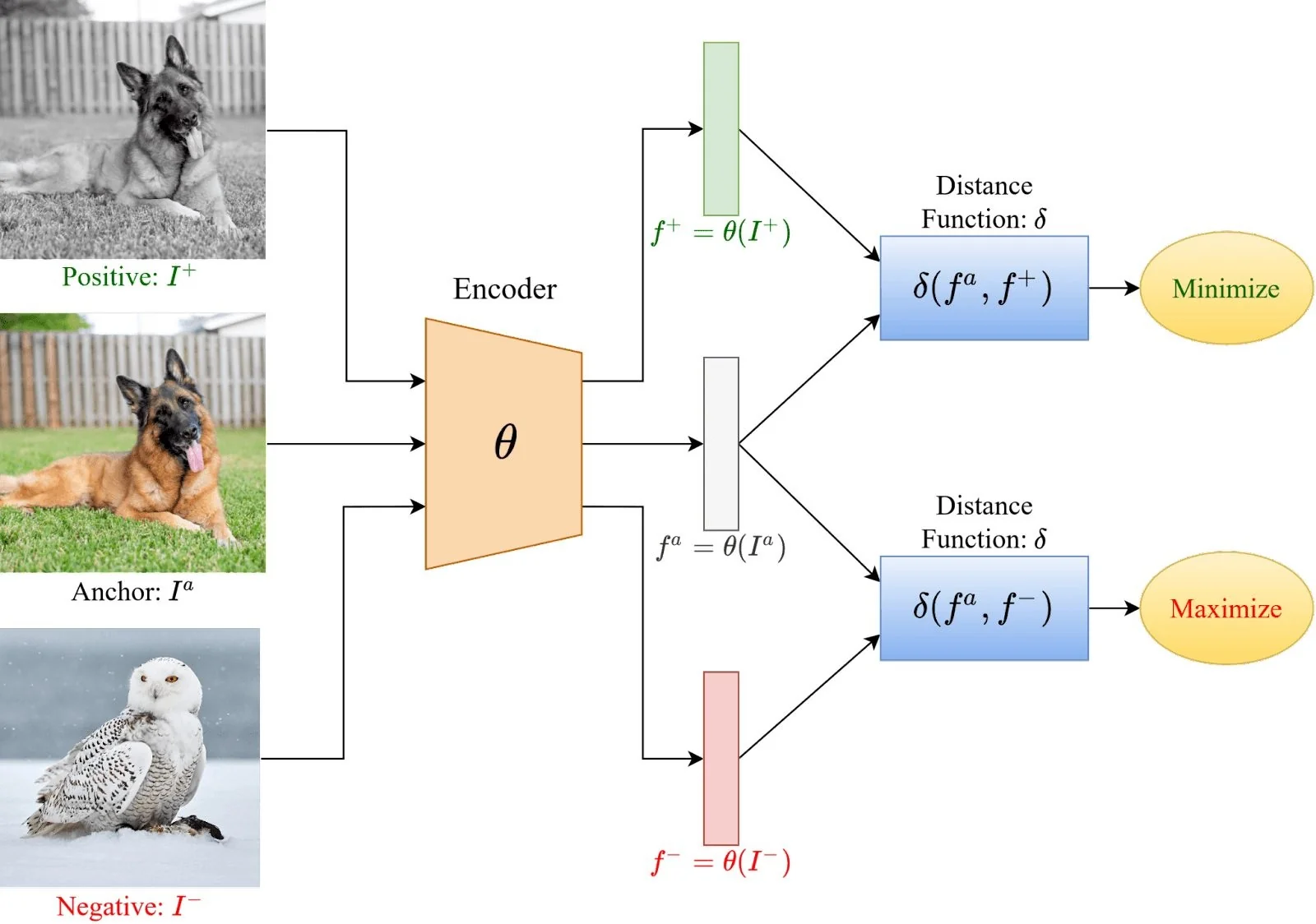

Triplet Setup: Anchor, Positive, Negative Every training batch uses:

- An anchor \( {I}^a \),

- A positive \( I^+ \), an augmented view of the anchor,

- Multiple negatives \( I^- \), views of different images.

The model learns to attract \( {I}^a \) and \( I^+ \), while repelling \( {I}^a \) from all \( I^- \).

This setting prepares the ground for more advanced losses like InfoNCE and NT-Xent, which we now derive.

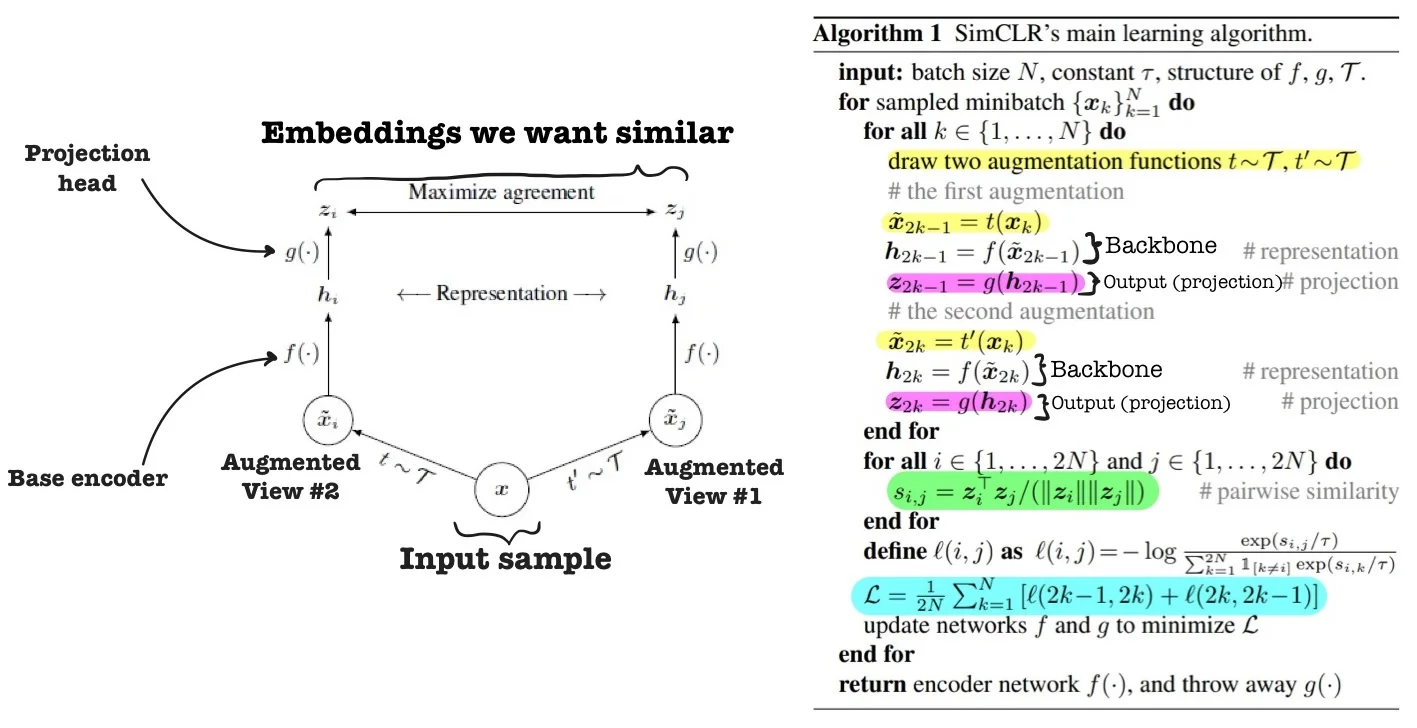

22.3.3 The NT-Xent Loss: Normalized Temperature-Scaled Cross-Entropy

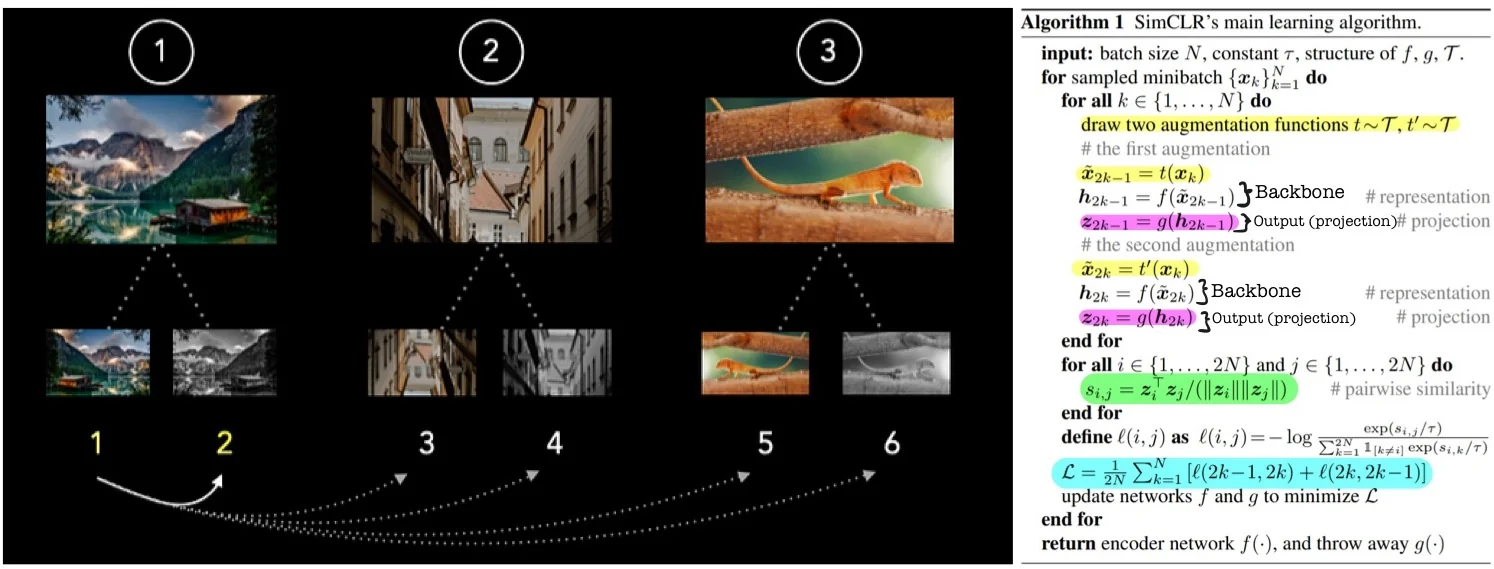

Overview and Purpose The NT-Xent loss (Normalized Temperature-Scaled Cross Entropy) was introduced in SimCLR [88] as a specialized instance of the broader InfoNCE loss. Its goal is to pull together embeddings of positive pairs—two different augmentations of the same image—while pushing apart negative pairs—augmentations of other images.

Unlike the more general InfoNCE, which allows a fixed number of negatives \(K\) (often stored in a memory bank), NT-Xent uses all other augmented samples within the batch as negatives. This batch-based construction, combined with cosine similarity and temperature scaling, makes NT-Xent self-contained, scalable, and well-suited for large-batch training without the need for external memory or momentum encoders.

Pairwise Contrastive Loss: NT-Xent Formulation Given a batch of \( N \) training images, SimCLR applies two independent stochastic data augmentations to each, resulting in \( 2N \) views. These are passed through a shared encoder \( f(\cdot ) \) followed by a projection head \( g(\cdot ) \), producing representations \( \{ \mathbf {z}_1, \mathbf {z}_2, \dots , \mathbf {z}_{2N} \} \subset \mathbb {R}^d \). Each original image thus yields a positive pair: \( (\mathbf {z}_{2k-1}, \mathbf {z}_{2k}) \) for \( k = 1, \dots , N \).

Let \( \mathrm {sim}(\mathbf {z}_i, \mathbf {z}_j) \) denote the cosine similarity between embeddings \( \mathbf {z}_i \) and \( \mathbf {z}_j \), both normalized to unit length: \[ \mathrm {sim}(\mathbf {z}_i, \mathbf {z}_j) = \frac {\mathbf {z}_i^\top \mathbf {z}_j}{\|\mathbf {z}_i\| \cdot \|\mathbf {z}_j\|} \in [-1, 1]. \]

The NT-Xent loss for a positive pair \( (i, j) \) is defined as: \[ \ell (i, j) = -\log \frac {\exp \left (\mathrm {sim}(\mathbf {z}_i, \mathbf {z}_j)/\tau \right )}{\sum _{k=1}^{2N} \mathbb {1}_{[k \ne i]} \exp \left (\mathrm {sim}(\mathbf {z}_i, \mathbf {z}_k)/\tau \right )}, \] where \( \tau > 0 \) is a temperature hyperparameter that scales the logits in the softmax.

This loss encourages each anchor \( \mathbf {z}_i \) to be more similar to its corresponding positive \( \mathbf {z}_j \) than to any of the \( 2N - 2 \) remaining negatives in the batch. Importantly, the positive \( j \) is included in the denominator as part of the softmax normalization—framing the task as (soft) classification among all other examples, with the correct match being \( j \).

Batch Aggregation and the \( \frac {1}{2N} \) Factor Each of the \( 2N \) augmented views serves once as an anchor. Hence, the total batch loss averages over all \( 2N \) such anchor-positive loss terms: \[ \mathcal {L}_{\mbox{NT-Xent}} = \frac {1}{2N} \sum _{k=1}^{N} \left [ \ell (2k - 1, 2k) + \ell (2k, 2k - 1) \right ]. \]

The normalization factor \( \frac {1}{2N} \) ensures that the total loss is the mean over all anchor-based comparisons. Each sample contributes exactly one anchor-to-positive term (and is a target once for its positive), and the symmetry ensures both directions are treated equally.

The Role of Symmetry In SimCLR, each image gives rise to two independently augmented views, forming a positive pair. For each such pair \((i, j)\), the NT-Xent loss is computed twice: once treating \(i\) as the anchor and \(j\) as the positive, and once with roles reversed. This symmetric loss formulation is not redundant—it is a principled mechanism that enforces bidirectional learning and representational consistency.

A common misconception is that if the representation \(i\) is optimized to be similar to \(j\), then \(j\) will automatically become similar to \(i\). While this holds for the cosine similarity itself—since \(\mbox{sim}(z_i, z_j) = \mbox{sim}(z_j, z_i)\)—it does not hold for the gradients of the loss. The NT-Xent objective applies a softmax over all non-anchor embeddings for each anchor. Thus, in \(\ell (i, j)\), \(z_i\) is compared against all other examples to classify \(z_j\) as its match. In contrast, \(\ell (j, i)\) uses \(z_j\) as the anchor and normalizes over a different softmax distribution. Despite the symmetry of the similarity metric, the loss landscapes—and therefore the gradients—are different for \(\ell (i, j)\) and \(\ell (j, i)\). As a result, omitting either direction would lead to asymmetric learning and potentially degraded representations for one side of the pair.

- Balanced gradient updates: Each of the \(2N\) views in a batch acts as an anchor exactly once. This guarantees that every view receives a direct learning signal and contributes symmetrically to parameter updates.

- Reciprocal alignment: Symmetric loss ensures that both views learn to identify their counterpart among many negatives, encouraging mutual semantic agreement across augmentations.

- Gradient diversity and stability: By computing the loss in both directions, the batch yields twice as many anchor-positive training signals. This increased supervision reduces gradient variance and stabilizes convergence.

- Stronger collapse prevention: Symmetry amplifies the discriminative pressure by requiring every view to be uniquely identifiable from its counterpart. This discourages degenerate solutions where all embeddings collapse to the same point.

In summary, the symmetric NT-Xent loss is essential for learning robust, discriminative, and augmentation-invariant representations. It ensures that both views of each instance are held equally accountable during training, preventing one-sided learning and promoting mutual consistency across the feature space.

Illustration of the Loss Mechanism

Role of the Projection Head SimCLR applies the NT-Xent loss not on the encoder output \( h_i = f(\tilde {x}_i) \), but on a transformed embedding \( z_i = g(h_i) \) produced by a non-linear projection head \( g(\cdot ) \). This architectural choice serves multiple roles:

- Enhanced contrastive learning: The projection head maps features into a latent space tailored for the contrastive objective, often improving training efficiency and downstream alignment.

- Disentangled optimization: By separating the encoder and contrastive spaces, SimCLR allows \( f(\cdot ) \) to focus on learning transferable representations, while \( g(\cdot ) \) handles the invariance constraints of the contrastive task.

- Downstream effectiveness: Empirically, the encoder outputs \( h \) outperform the projected representations \( z \) on downstream tasks. This suggests that \( g(\cdot ) \) discards non-semantic variation useful only during pretraining—preserving generality in \( f(\cdot ) \).

For each positive pair, we want the similarity score \( s_{i,j} \) to dominate the softmax numerator, while all other similarity scores are minimized in the denominator. This aligns positive pairs and repels negative ones in angular space.

Summary NT-Xent effectively replaces the contrastive margin in Hadsell’s formulation with a temperature-scaled softmax. It eliminates the need for threshold tuning, is differentiable everywhere, and naturally fits into batch-wise contrastive pipelines.

We now examine two key contrastive frameworks: SimCLR, which uses NT-Xent with large in-batch negatives, and MoCo, which introduces a momentum encoder and memory queue for scalable contrastive learning. We start with SimCLR, then follow MoCo through its three versions.

22.3.4 SimCLR: A Simple Framework for Contrastive Learning

Overview SimCLR [88] introduced a surprisingly simple yet powerful framework for self-supervised contrastive learning that achieved state-of-the-art performance using standard architectures and without requiring negative mining tricks or memory banks. Its core training objective is the NT-Xent loss, introduced in part 22.3.3, which pulls together positive pairs while pushing apart negatives in the embedding space.

Architecture Components The SimCLR framework is composed of the following components:

- Stochastic Data Augmentation Module: Each image is transformed into two augmented views using strong random transformations (e.g., random cropping, color distortion, blur), forming a positive pair. Other images in the batch form negative pairs.

- Encoder Network \( f(\cdot ) \): A standard ResNet (e.g., ResNet-50) extracts a representation vector \( {h} \in \mathbb {R}^d \) from each augmented view.

- Projection Head \( g(\cdot ) \): A small MLP maps \( {h} \) to a lower-dimensional vector \( {z} = g({h}) \), on which the contrastive loss is applied.

The paper’s critical finding is that while contrastive training is applied to \( {z} \), the upstream encoder output \( {h} \) consistently yields better performance on downstream tasks. The projection head thus acts as a form of task-specific decoupling, allowing the encoder to retain general-purpose semantics while contrastive alignment occurs in \( {z} \)-space.

Design Principles Behind SimCLR Beyond its loss function, SimCLR’s success hinges on several essential design insights:

- Strong Data Augmentations Are Crucial: SimCLR demonstrated empirically that augmentations such as random crop, color distortion, and Gaussian blur are not mere regularizers but define the pretext task by creating diverse views of the same image.

- Importance of the Projection Head: Removing the non-linear head or applying the contrastive loss directly on \( {h} \) significantly degraded performance. This architectural separation was essential for avoiding information loss and achieving strong transferability.

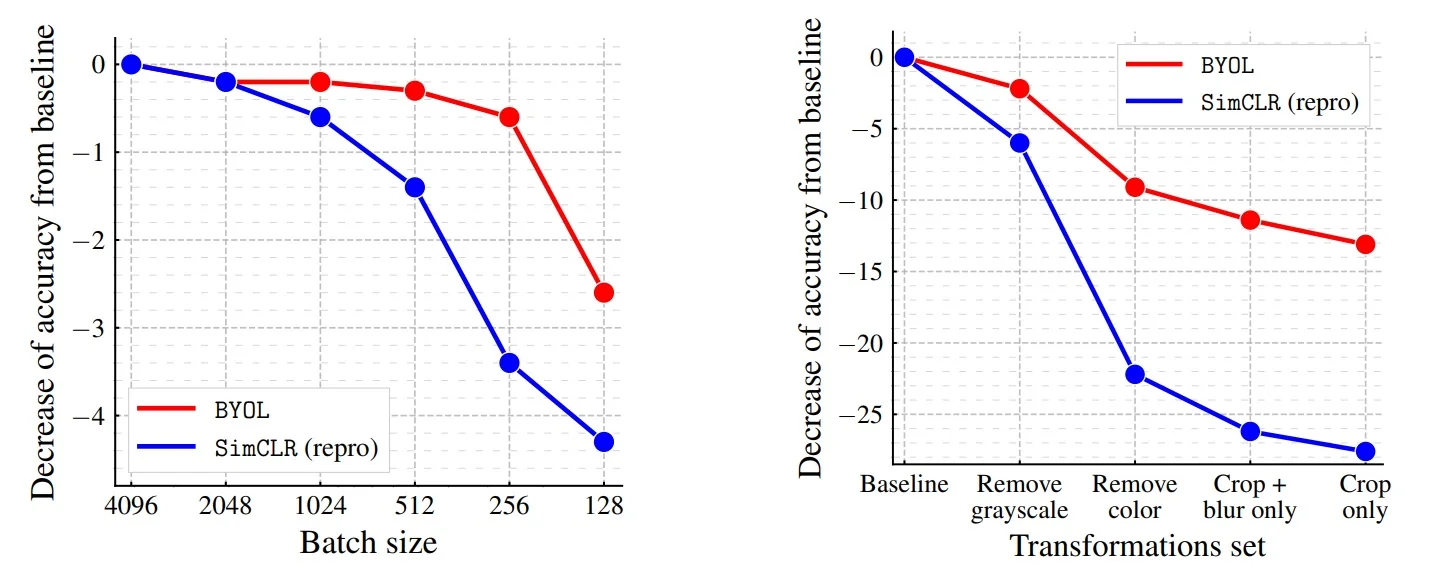

- Large Batch Sizes: NT-Xent is computed over all other \( 2N-2 \) samples as negatives. Larger batches improve the quality of negative sampling, and SimCLR scaled up to batch sizes of 8192 using 128 TPU cores.

- Temperature Scaling: The temperature parameter \( \tau \) controls the sharpness of the similarity distribution and strongly affects performance. Lower values increase contrastiveness but can destabilize training; careful tuning is needed.

Training Configuration and Stability SimCLR’s strong performance was not only due to its contrastive loss and data augmentations, but also to its rigorous training setup. The model was trained for 1000 epochs—an unusually long schedule—using large batch sizes of up to 8192.

These batch sizes are essential for generating a sufficient number of negative examples within each batch (e.g., 16,382 negatives per positive pair at batch size 8192). To enable stable optimization under such conditions, SimCLR used the LARS optimizer [738], which supports large-batch training with high learning rates.

The learning rate followed a linear warm-up for the first 10 epochs, followed by a cosine decay schedule without restarts. Training also relied heavily on strong data augmentations, including color distortions, random cropping, and Gaussian blur, which proved more impactful for contrastive learning than for supervised settings. Despite its conceptual simplicity, SimCLR was computationally intensive: a full 1000-epoch training of ResNet-50 required multiple days on TPU pods or dozens of V100 GPUs.

Performance Benchmarks SimCLR established new benchmarks for self-supervised learning:

- Linear evaluation protocol: When training a linear classifier atop frozen features, SimCLR achieved 76.5% top-1 accuracy on ImageNet with a ResNet-50 encoder—on par with fully supervised ResNet-50 models. This confirmed that self-supervised pretraining could match label-based training in representation quality.

- Label efficiency: In semi-supervised settings, SimCLR dramatically outperformed supervised baselines. Fine-tuning on just 1% of ImageNet labels yielded substantially better accuracy than supervised models trained on the same data subset. This demonstrates the method’s exceptional ability to learn from scarce annotations.

- Transferability: SimCLR’s representations transferred effectively to downstream tasks beyond ImageNet. Across 12 natural image classification datasets, SimCLR matched or surpassed a supervised ResNet-50 baseline on 10 of them, demonstrating robustness and generality.

These results highlight that scaling contrastive learning—through larger batches, longer training, and effective augmentations—can yield powerful representations without the need for human labels, and can generalize across domains.

Visualization of SimCLR Pipeline

Limitations and the Road to MoCo Despite its success, SimCLR suffers from a key limitation: its reliance on extremely large batch sizes. Since all negatives are sampled in-batch, sufficient diversity requires thousands of negatives per anchor—demanding massive compute. This constraint motivates subsequent approaches such as MoCo, which replace batch-based negatives with a dynamic memory bank and a momentum encoder, offering comparable performance with smaller batches.

We now turn to MoCo [211], a method that addresses this limitation by introducing a scalable and memory-efficient alternative to batch-based contrastive learning.

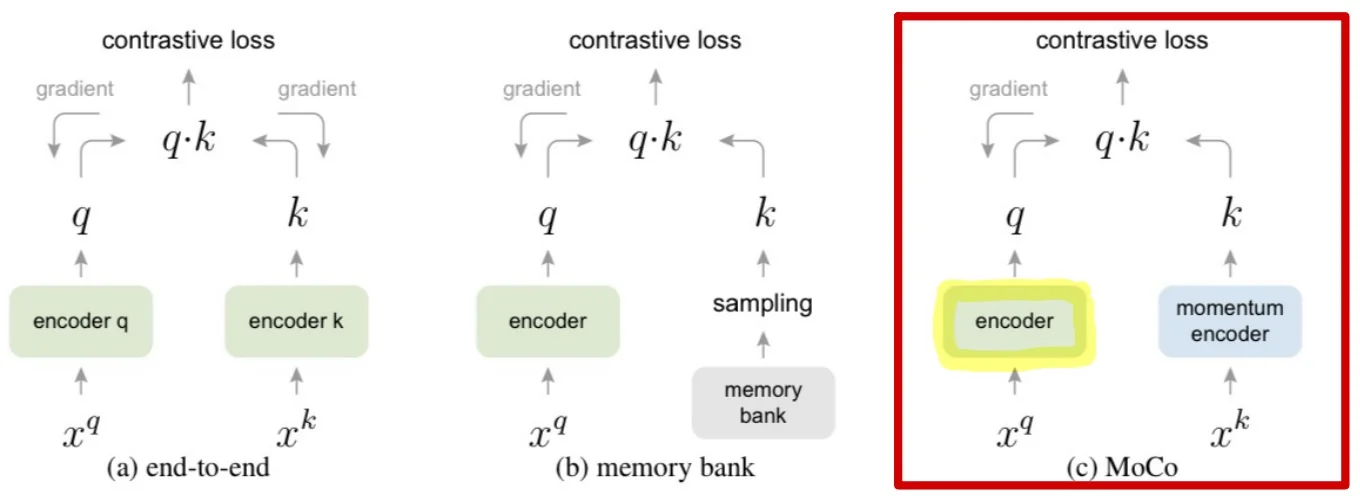

22.3.5 Momentum Contrast (MoCo)

Motivation: Avoiding Large Batch Sizes SimCLR demonstrated that contrastive learning benefits significantly from large numbers of negative examples. However, it used in-batch negatives only, meaning the number of negatives was tied to the batch size. To provide over 8000 negatives per anchor (as in SimCLR), one must train with prohibitively large batches—e.g., 8192 samples—across dozens of GPUs with high memory budgets.

MoCo [211] was introduced to overcome this scalability bottleneck. Its core idea is to decouple the number of negatives from the batch size by maintaining a large, dynamic dictionary (queue) of past embeddings. It also introduces a momentum encoder to ensure that the representations stored in this queue evolve slowly and remain consistent over time—enabling effective contrastive learning with a small batch and many stable negatives (previously stored in a FIFO queue).

Core Architecture MoCo adopts an asymmetric dual-encoder architecture, consisting of:

- Query encoder \( f_q \): a standard neural network (e.g., ResNet-50) trained via backpropagation.

- Key encoder \( f_k \): a second encoder with the same architecture, whose parameters are updated as a moving average of \( f_q \): \[ \theta _k \leftarrow m \cdot \theta _k + (1 - m) \cdot \theta _q \] This momentum update with \( m \approx 0.999 \) ensures that \( f_k \) evolves slowly, producing temporally consistent keys that can be stored in a queue and reused as negatives across multiple steps.

Terminology note. MoCo replaces the classical anchor–positive–negative triplet terminology with the more functional terms query (trainable view) and key (reference views). The positive key comes from the same image as the query, while negatives are sampled from the memory queue.

Contrastive Loss in MoCo MoCo adopts the InfoNCE loss, mathematically identical to the NT-Xent loss in SimCLR. For a query \( q = f_q(x_q) \), a positive key \( k^+ = f_k(x_k^+) \), and a set of negatives \( \{ k_i^- \} \) drawn from the queue \( \mathcal {K} \), the loss is: \[ \mathcal {L}_{\mbox{MoCo}} = -\log \frac {\exp (q \cdot k^+ / \tau )}{\exp (q \cdot k^+ / \tau ) + \sum _{k^- \in \mathcal {K}} \exp (q \cdot k^- / \tau )} \] The query and its positive key are two augmentations of the same image, while the negatives come from different images (past embeddings stored in the queue).

MoCo Training Pipeline Each training step proceeds as follows:

- 1.

- Sample a batch of images; for each image, create two augmentations: \( x_q \) and \( x_k \).

- 2.

- Pass \( x_q \) through the query encoder \( f_q \) to produce the query \( q \).

- 3.

- Pass \( x_k \) through the key encoder \( f_k \) to obtain the key \( k^+ \). No gradients flow through \( f_k \).

- 4.

- Compute the InfoNCE loss between \( q \), \( k^+ \), and negatives \( \{ k^- \} \) in the queue.

- 5.

- Backpropagate gradients to update \( f_q \).

- 6.

- Update \( f_k \) using exponential moving average (EMA) of \( f_q \).

- 7.

- Enqueue the new key \( k^+ \) and dequeue the oldest key to maintain queue size.

Why MoCo Works: Scale, Stability, and Efficiency MoCo addresses two core challenges in contrastive learning: the need for many negatives and the requirement for stable targets. Its architecture offers a scalable and hardware-efficient alternative to large-batch contrastive methods like SimCLR.

- Large-scale negatives without large batches: In SimCLR, negatives are limited to samples within the current batch, requiring extremely large batch sizes (e.g., 8192) to match the number of negatives MoCo can access. MoCo overcomes this limitation through a dynamic queue: a FIFO buffer of encoded key representations from prior mini-batches. This decouples the number of negatives from the current batch size, allowing MoCo to leverage tens of thousands of negatives per step (e.g., a queue of 65,536) while training with batches as small as 256—greatly reducing the compute and memory burden.

- Stable representations through momentum: To ensure that the queue remains semantically consistent with the current encoder, MoCo employs a momentum encoder. The key encoder \( f_k \) is updated as an exponential moving average (EMA) of the query encoder \( f_q \): \[ \theta _k \leftarrow m \cdot \theta _k + (1 - m) \cdot \theta _q \] A high momentum (e.g., \( m = 0.999 \)) ensures that \( f_k \) evolves slowly across training steps. This stabilizes the embeddings stored in the queue and prevents contrastive comparisons from drifting out of alignment. Without this slow evolution, earlier keys would quickly become obsolete, leading to noisy or contradictory learning signals.

- Asymmetric training improves robustness: Only the query encoder \( f_q \) is trained with gradients, while the key encoder \( f_k \) passively tracks it via momentum. This architectural asymmetry improves training stability, reduces memory requirements, and avoids collapse. By decoupling the learning dynamics of the two encoders, MoCo implicitly regularizes the training objective, making the contrastive task more stable and better behaved.

What the Queue Enables Unlike SimCLR, which must compute all negatives on-the-fly within the current batch, MoCo separates negative storage from computation. This leads to multiple advantages:

-

Extremely large dictionaries: MoCo’s queue holds thousands of negatives—potentially 100× more than what can fit in a single batch. This increases the diversity of the contrastive signal and improves the model’s ability to discriminate among fine-grained features in high-dimensional space.

- Efficient memory and compute: Only the current batch is encoded by \( f_q \) and \( f_k \), while prior embeddings are reused from the queue without recomputation. This constant per-step cost enables MoCo to scale up the effective batch size without scaling GPU memory usage.

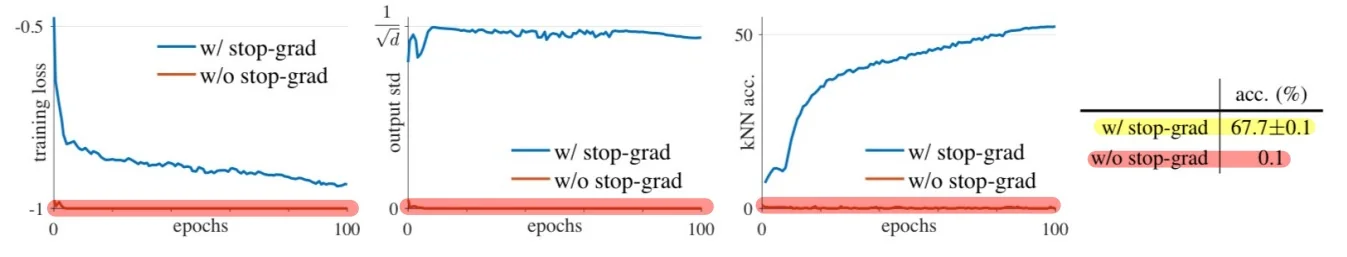

- Temporal coherence: The queue is updated at each step by enqueuing newly encoded positive keys and removing the oldest entries. Because the key encoder evolves slowly via EMA, even old entries in the queue remain consistent with the current representation space. Without this, the contrastive task would break down—indeed, MoCo fails to train when \( m = 0 \).

Momentum Hyperparameter Tuning and Ablation Results A central component of MoCo’s architecture is the momentum-based update of the key encoder \( f_k \), governed by an exponential moving average (EMA):

\[ \theta _k \leftarrow m \cdot \theta _k + (1 - m) \cdot \theta _q \]

Here, \( \theta _q \) and \( \theta _k \) denote the parameters of the query and key encoders, respectively, and \( m \in [0, 1) \) is the momentum coefficient.

This update rule ensures that the representations stored in the queue—many of which were computed several iterations earlier—remain temporally consistent with the current query space. A high momentum slows the evolution of \( f_k \), thereby maintaining coherence among the stored negatives. In contrast, a low momentum causes \( f_k \) to change rapidly, making the queue misaligned with the current query distribution and impairing training.

| \( m \) | 0 | 0.9 | 0.99 | 0.999 | 0.9999 |

| Accuracy (%) | fail | 55.2 | 57.8 | 59.0 | 58.9 |

As shown in Table 22.2, the model’s performance is highly sensitive to the value of \( m \). When \( m = 0 \), MoCo fails entirely—the key encoder becomes a direct copy of the query encoder, causing the queue to drift erratically and undermining consistency. At the other extreme, very high momentum values (e.g., \( m = 0.999 \)) yield the best performance by preserving alignment across steps while still allowing the queue to adapt gradually. These findings emphasize that consistency is more important than freshness in maintaining a reliable dictionary for contrastive learning.

Other Key Ablations and Design Justifications In addition to momentum tuning, the MoCo v1 paper includes several important ablations that support its architectural decisions:

- Queue size \( K \): Larger queues consistently improve performance. Increasing \( K \) from 4,096 to 65,536 enables access to more diverse negatives without great additional computational cost, as only the current mini-batch is encoded.

-

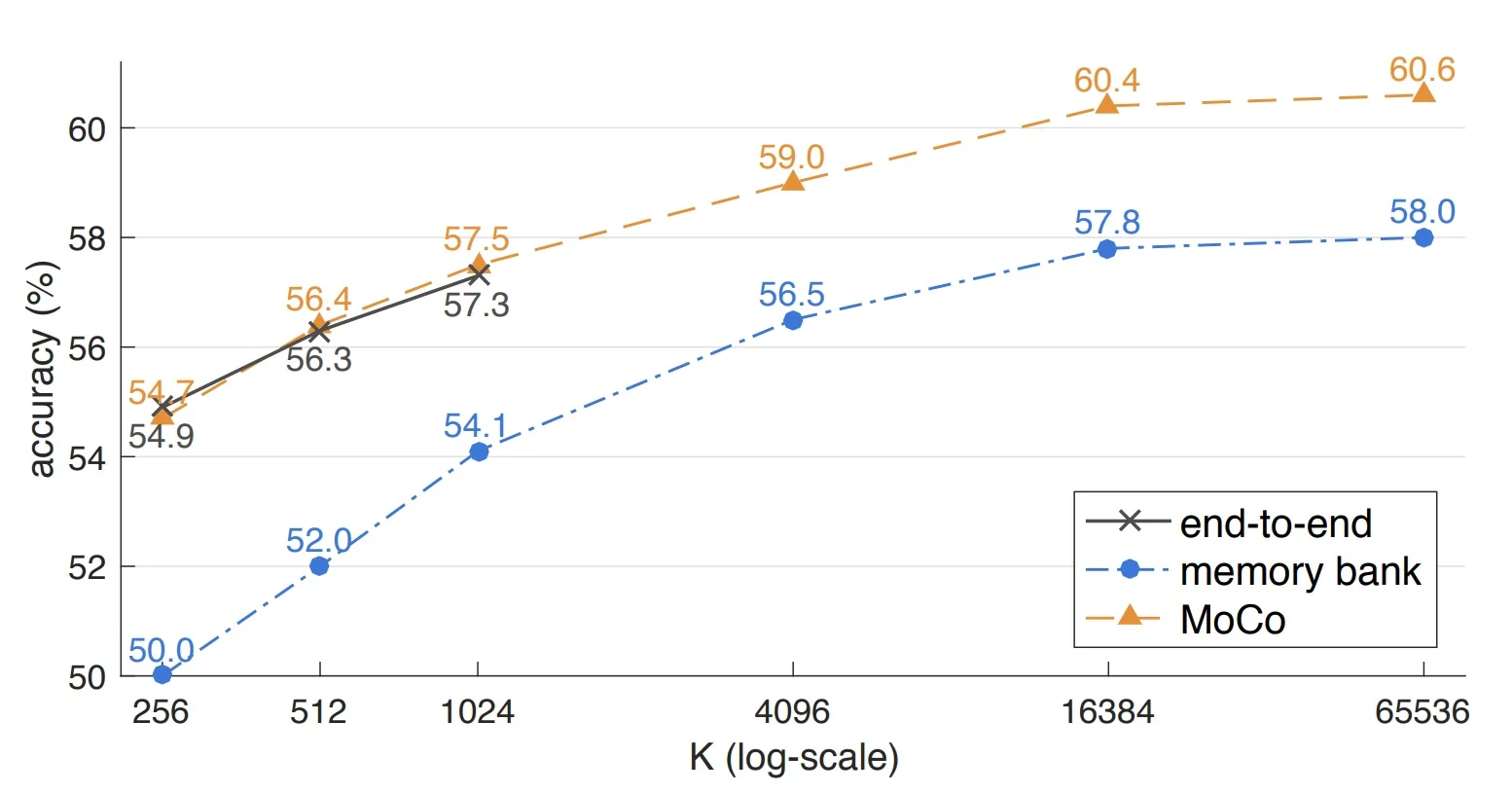

Contrastive loss mechanisms: MoCo is compared to two alternatives: (i) a memory bank that stores outdated keys, and (ii) an end-to-end encoder that uses in-batch negatives. All mechanisms benefit from larger negative sets, but MoCo outperforms the others by maintaining both scale and temporal consistency.

Figure 22.12: Comparison of three contrastive loss mechanisms on the ImageNet linear classification benchmark using a ResNet-50 backbone. All models share the same pretext task and differ only in their contrastive design. The number of negatives is \( K \) for MoCo and memory bank methods, and \( K - 1 \) for end-to-end approaches (excluding the positive sample). MoCo matches or surpasses the accuracy of both alternatives by combining a large pool of negatives with temporally consistent embeddings—achieving strong performance without relying on massive batches or tolerating stale keys. Source: [211]. -

Shuffling BatchNorm: In distributed training, naive use of Batch Normalization (BN) can introduce information leakage between the query and key branches. Since BN computes statistics across a batch, both the query and its corresponding positive key—if processed within the same synchronized batch—may indirectly share feature information through shared normalization. This enables the model to ”cheat” the pretext task by manipulating BN statistics, resulting in artificially low loss without truly learning semantic structure.

To mitigate this, MoCo applies batch shuffling for the key encoder: samples are randomly permuted before being distributed across GPUs. As a result, the BN statistics used in the query and key branches are computed over different sample subsets. This decouples their normalization pathways and forces the model to solve the contrastive task based on actual feature alignment rather than statistical shortcuts. Ablation results show that disabling this trick leads to significant performance degradation, underscoring its role in enabling genuine contrastive learning.

- Transfer performance: MoCo’s learned representations generalize well to downstream tasks. When fine-tuned on PASCAL VOC, COCO detection, or keypoint estimation, MoCo-pretrained models often outperform supervised counterparts, especially under low-data regimes.

Together, these results establish MoCo as a scalable and principled solution to the limitations of in-batch contrastive methods. Its success laid the groundwork for subsequent improvements in MoCo v2 and MoCo v3.

Performance and Comparison with SimCLR MoCo achieves comparable results (though lesser in this version) to SimCLR with dramatically lower resource demands:

| Aspect | SimCLR | MoCo |

|---|---|---|

| Negatives Source | In-batch only | External memory queue |

| Batch Size Requirement | Very large (up to 8192) | Small/moderate (e.g., 256) |

| Architectural Symmetry | Symmetric (same encoder) | Asymmetric (EMA target) |

| Update Mechanism | SGD on both encoders | SGD + EMA |

| Memory Usage | High (due to batch size) | Efficient |

| Collapse Prevention | Large batch + symmetry | Stable queue + EMA encoder |

From MoCo v1 to MoCo v2 MoCo v1 successfully decoupled negative sampling from batch size, enabling scalable contrastive learning with modest compute. However, its initial formulation was deliberately minimal—focused on demonstrating feasibility rather than achieving state-of-the-art accuracy. This left room for improvement. MoCo v2 [95] builds directly on the core architecture of MoCo v1 but integrates empirical best practices from SimCLR, including stronger data augmentations, a deeper nonlinear projection head, and cosine learning rate decay. These enhancements are orthogonal to the momentum-queue mechanism and can be applied without changing MoCo’s fundamental contrastive structure. As a result, MoCo v2 significantly boosts linear evaluation performance, closing the gap with—and in some settings surpassing—SimCLR, all while maintaining the efficiency and stability of the original framework.

22.3.6 MoCo v2 and MoCo v3

From MoCo v1 to v2: Architectural Refinements Following the success of MoCo [211], the second version—MoCo v2 [95]—introduced two impactful modifications inspired by SimCLR [88]:

- Replacing the ResNet encoder’s linear head with a 2-layer MLP projection head (2048-d hidden layer, ReLU nonlinearity).

- Augmenting the training pipeline with stronger augmentations, specifically adding Gaussian blur.

While these changes appear minor, they yield significant accuracy gains during unsupervised training. Notably, MoCo v2 maintains MoCo v1’s core design: a dynamic queue of negative keys and a momentum encoder. These enhancements allow MoCo v2 to surpass SimCLR in performance—despite requiring significantly smaller batch sizes.

MLP Head and Temperature Ablation. The following table—based on results from [95]—highlights the influence of the MLP projection head and temperature parameter \( \tau \) on ImageNet linear classification accuracy:

| \(\tau \) | 0.07 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| w/o MLP | 60.6 | 60.7 | 59.0 | 58.2 | 57.2 | 56.4 |

| w/ MLP | 62.9 | 64.9 | 66.2 | 65.7 | 65.0 | 64.3 |

Comparison with SimCLR. As further demonstrated in Table 22.5, MoCo v2 [95] achieves competitive or superior performance compared to SimCLR, despite using significantly smaller batch sizes and fewer computational resources.

MoCo v3: Adapting Momentum Contrast to Vision Transformers With the rise of Vision Transformers (ViTs) [133], MoCo v3 [93] extended the momentum contrastive learning framework beyond convolutional backbones. It introduces several architectural and algorithmic updates that make it well-suited for training Transformer-based encoders in a scalable, stable, and contrastive manner.

Key innovations of MoCo v3 include:

- Removal of the memory queue: Unlike MoCo v1 and v2, MoCo v3 discards the dictionary queue and adopts an in-batch negatives strategy like SimCLR. This is made viable by scaling up batch sizes (e.g., 2048–4096), ensuring sufficient negative diversity without external memory.

- Symmetric contrastive loss: Previous versions used an asymmetric loss—queries were trained to match fixed keys. In MoCo v3, both augmented views are treated symmetrically: the loss is computed as \( \mathcal {L}(q_1, k_2) + \mathcal {L}(q_2, k_1) \), leveraging the full batch and encouraging bi-directional alignment.

- Non-shared prediction head: A learnable prediction MLP is appended only to the query encoder \( f_q \). This design, borrowed from BYOL, avoids trivial alignment and improves training stability by introducing asymmetry between encoders.

-

Frozen random patch projection in ViTs: MoCo v3 introduces a seemingly counter-intuitive yet effective design: when using ViTs, the patch projection layer—which maps image patches into token embeddings—is randomly initialized and then frozen. This layer is not trained; instead, a stop-gradient operator is applied immediately after it. The rationale stems from a key observation: during self-supervised ViT training, sharp gradient spikes frequently originate in the shallowest layers, particularly the patch projection. These spikes cause unstable optimization and mild accuracy degradation (e.g., 1–3%). Freezing this projection layer eliminates this instability, yielding smoother loss curves and higher final accuracy.

Importantly, the frozen projection still preserves input information due to the overcomplete nature of the embedding (e.g., mapping from 768 raw pixels to a 768-dimensional vector), making random projection surprisingly effective. While it may seem preferable to use a pretrained patch embedder, doing so would violate the self-supervised training regime’s independence from labeled data. The frozen random projector thus offers a principled compromise: it avoids instability without introducing supervision or sacrificing downstream performance.

These architectural innovations result in a streamlined and highly effective self-supervised training procedure. The following pseudocode illustrates the core training loop of MoCo v3 in PyTorch-like syntax, highlighting the interplay between query and key encoders, augmentation symmetry, and momentum updates:

# f_q: backbone + projection MLP + prediction MLP

# f_k: backbone + projection MLP (momentum-updated)

# m: momentum coefficient

# t: temperature

for x in loader: # Load a minibatch of N samples

x1, x2 = aug(x), aug(x) # Two random augmentations per sample

q1, q2 = f_q(x1), f_q(x2) # Query embeddings (with pred head)

k1, k2 = f_k(x1), f_k(x2) # Key embeddings (no pred head)

loss = ctr(q1, k2) + ctr(q2, k1) # Symmetric InfoNCE loss

loss.backward()

update(f_q) # SGD update for query encoder

f_k = m * f_k + (1 - m) * f_q # EMA update for key encoderLoss Function. MoCo v3 uses a symmetric InfoNCE loss computed over in-batch negatives. Each query is matched to its corresponding key, and all other entries in the batch act as negatives:

def ctr(q, k):

logits = mm(q, k.t()) # NxN cosine similarities

labels = range(N) # Positive pairs on the diagonal

loss = CrossEntropyLoss(logits/t, labels)

return 2 * t * loss # Scaling to match SimCLR conventionThis formulation treats each pair \( (q_i, k_i) \) as positive, and the remaining \( N - 1 \) entries in each row as negatives. The temperature \( t \) adjusts the sharpness of the distribution, and the scaling factor \( 2t \) compensates for the bidirectional loss.

Why Symmetric Loss? Earlier MoCo variants used an asymmetric loss because they relied on an external queue whose keys were not mutually comparable. MoCo v3, by operating on synchronized in-batch keys, can safely match both \( q_1 \rightarrow k_2 \) and \( q_2 \rightarrow k_1 \). This symmetry increases gradient diversity, ensures both views act as anchors, and improves the robustness of learned representations.

- The query encoder \( f_q \) is updated via SGD and includes both a projection and prediction head.

- The key encoder \( f_k \) is updated via exponential moving average (EMA) of \( f_q \), and has no prediction head.

- The contrastive loss uses all \( N - 1 \) in-batch samples as negatives for each query.

- Symmetric training ensures both augmented views serve equally as anchor and target, avoiding representational bias.

Performance Highlights MoCo v3 achieves state-of-the-art results on ImageNet using both CNN and ViT backbones. Tables 22.6 and 22.7 show MoCo v3 outperforming or matching alternatives like BYOL and SimCLR across multiple settings.

| Backbone | ViT-B | ViT-L | ViT-H |

| Linear Probing | 76.7 | 77.6 | 78.1 |

| End-to-End Finetuning | 83.2 | 84.1 | – |

Takeaway MoCo v3 elegantly unifies contrastive learning with Transformer architectures by (1) removing the queue, (2) adopting a symmetric InfoNCE loss, and (3) introducing practical stability mechanisms like frozen embeddings and non-shared heads. These changes not only boost performance but also simplify training and broaden applicability across vision architectures.

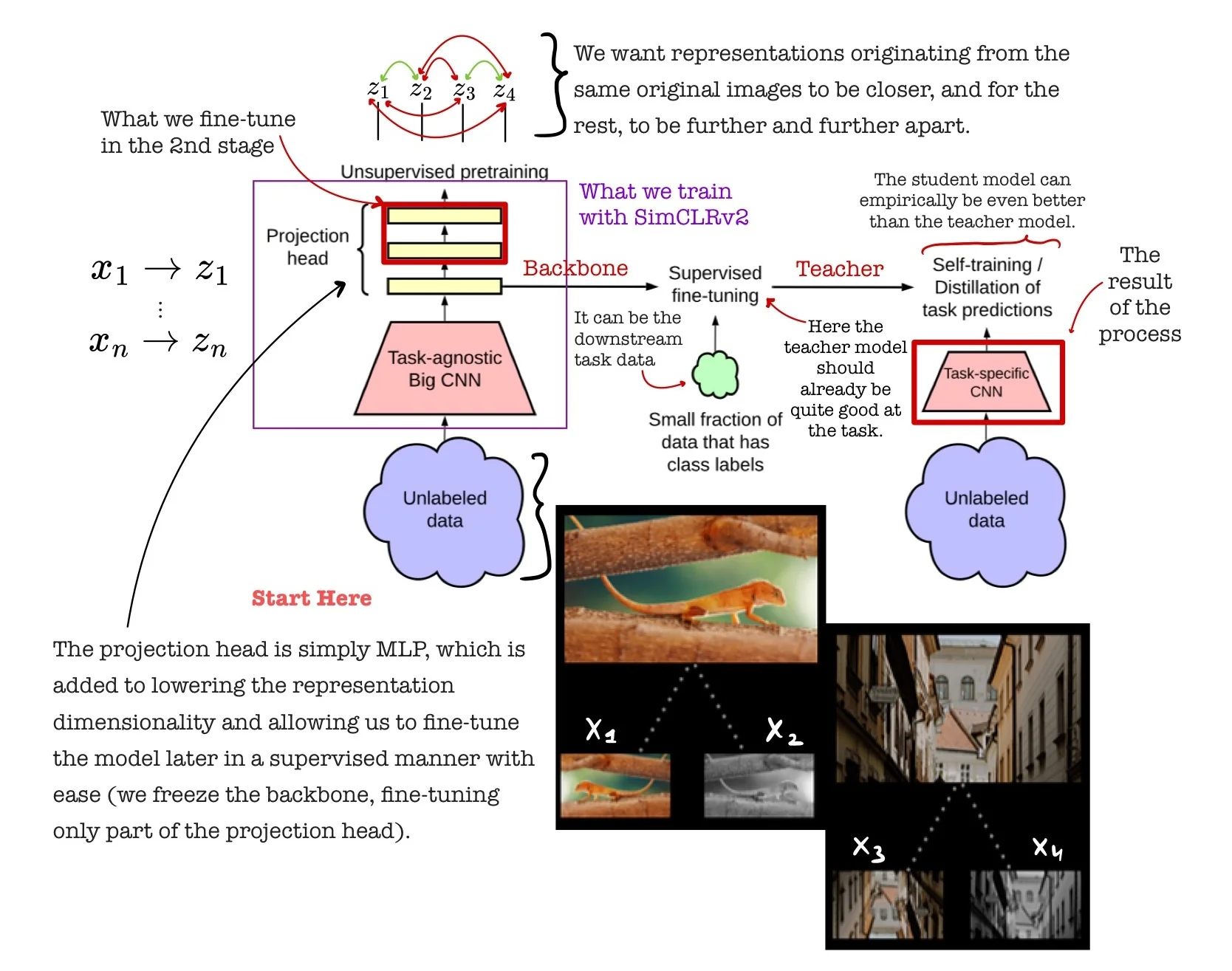

22.3.7 SimCLR v2: Scaling Contrastive Learning for Semi-Supervised Settings

Motivation and Overview SimCLR v1 [88] showed that strong visual representations can be learned without labels by leveraging contrastive learning with the NT-Xent loss (see 22.3.3). However, its focus was limited to unsupervised pretraining with moderate architectures and did not provide a full pipeline for label-efficient learning. To address this, SimCLR v2 [89] introduces a scalable and modular framework that unifies contrastive pretraining, supervised fine-tuning, and self-distillation. The result is a general-purpose pipeline for semi-supervised learning that achieved (at the time of publication) state-of-the-art performance in low-label regimes, while also improving linear evaluation and transfer capabilities.

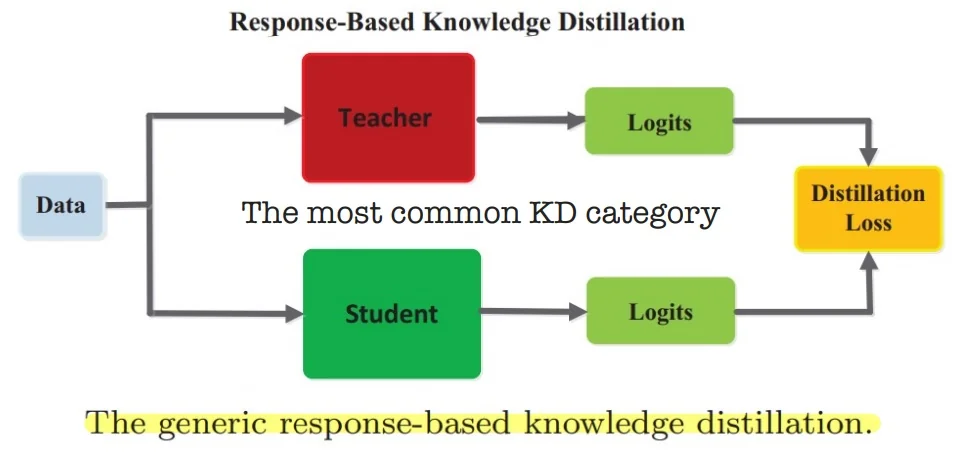

Three-Stage Training Framework SimCLR v2 introduces a structured pipeline that combines large-scale self-supervised pretraining, label-efficient supervised fine-tuning, and knowledge distillation. This enables strong performance in both self- and semi-supervised regimes by leveraging unlabeled data at scale and making effective use of limited labels.

- 1.

- Unsupervised Pretraining: A high-capacity encoder (e.g., ResNet-152 or ResNet-152+SK) is trained using the SimCLR contrastive objective on large-scale unlabeled data. This stage learns augmentation-invariant features by bringing together representations of the same image under different views while repelling those from different images. Larger encoders capture more diverse semantic structure, aiding downstream generalization.

- 2.

- Supervised Fine-tuning: The pretrained encoder is fine-tuned on a small labeled subset (e.g., 1–10% of ImageNet). Rather than discarding the projection head, fine-tuning starts from an intermediate layer (layer_2) of the MLP, preserving useful invariances and improving performance under low-label settings.

- 3.

- Knowledge Distillation: The fine-tuned model acts as a teacher for a student network, which is trained on unlabeled data using soft labels (logits or probabilities). These soft targets encode inter-class structure and uncertainty, guiding the student to learn smoother and more generalizable decision boundaries. Surprisingly, the student can even outperform the teacher.

Architectural Enhancements and Ablation Insights SimCLR v2 enhances SimCLR v1 through several key refinements:

- Larger Encoders: Using deeper and wider networks, such as ResNet-152+SK, improves representation quality learned from unlabeled data.

- Three-Layer Projection Head: The projection MLP \( g(\cdot ) \), extended from 2 to 3 layers, \[ z = W_3 \cdot \mbox{ReLU}(W_2 \cdot \mbox{ReLU}(W_1 h)), \] increases the head’s expressiveness for contrastive learning while decoupling it from the encoder \( f(\cdot ) \), which remains focused on learning transferable features.

- Mid-layer Fine-tuning: Fine-tuning from the second hidden layer of \( g(\cdot ) \) bridges pretraining and downstream tasks, acting as a task-adaptive adapter and improving label efficiency.

Why Distillation Works The distillation step enables the student to benefit from the teacher’s knowledge—even exceeding it—through several mechanisms:

- Soft Targets as Rich Supervision: Unlike hard labels, soft labels encode class similarities and model uncertainty, offering a smoother and more informative learning signal.

- Regularization via Teacher Guidance: The teacher’s outputs act as denoised supervision, reducing overfitting to limited labels and improving generalization.

- Expanded Supervision from Unlabeled Data: By assigning soft labels to the entire unlabeled set, the student trains on a vastly expanded pseudo-labeled dataset.

- Simpler Optimization Objective: Mimicking the teacher’s output distribution is often easier than learning the task from scratch with limited labels, enabling more stable and efficient training.

- Student Surpassing Teacher: The student can outperform its teacher because it trains on more data (via distillation) with richer supervision, while regularized by the teacher’s knowledge.

Quantitative Results and Analysis To assess SimCLR v2’s performance under semi-supervised conditions, the authors evaluate its accuracy on ImageNet using 1% and 10% of labels. Following a two-stage protocol—self-supervised pretraining followed by supervised fine-tuning and distillation—SimCLR v2 achieves substantial improvements over both prior self-supervised methods and strong semi-supervised baselines. The table below reports Top-1 and Top-5 accuracy using various ResNet architectures and training setups.

| Method | Architecture | 1% T1 | 1% T5 | 10% T1 | 10% T5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Supervised baseline [89] | ResNet-50 | 25.4 | 48.4 | 56.4 | 80.4 |

| SimCLR v1 [88] | R-50 (4\(\times \)) | 63.0 | 85.8 | 74.4 | 92.6 |

| BYOL [188] | R-200 (2\(\times \)) | 71.2 | 89.5 | 77.7 | 93.7 |

| SimCLR v2 (distilled) | R-50 | 73.9 | 91.5 | 77.5 | 93.4 |

| SimCLR v2 (distilled) | R-50 (2\(\times \)+SK) | 75.9 | 93.0 | 80.2 | 95.0 |

| SimCLR v2 (self-distilled) | R-152 (3\(\times \)+SK) | 76.6 | 93.4 | 80.9 | 95.5 |

Table 22.8 shows that with just 1% of labels (approximately 13 images per class), SimCLR v2 with ResNet-152 (3\(\times \) wider + SK convolutions) achieves 76.6% Top-1 accuracy and 93.4% Top-5 accuracy, outperforming all prior methods.

| Training Setup | 1% Labels | 10% Labels |

|---|---|---|

| Label only | 12.3 | 52.0 |

| Label + distill (labeled only) | 23.6 | 66.2 |

| Label + distill (labeled + unlabeled) | 69.0 | 75.1 |

| Distill only (unlabeled only) | 68.9 | 74.3 |

Table 22.9 presents ablations on distillation strategy. Notably, a comparable performance to the best one is achieved even without any labeled examples during the distillation phase. This demonstrates the strength of soft-label supervision: learning from the teacher’s logits—even on fully unlabeled data—transfers robust knowledge.

Table 22.10 reports linear evaluation accuracy for ResNet-50 (1\(\times \)) backbones. SimCLR v2 substantially improves over SimCLR v1 and MoCo v2, nearly matching the fully supervised model despite using no labels during pretraining.

Conclusion The SimCLR family demonstrates the power of contrastive learning to scale with model capacity and data availability. Starting from its first version [88], which emphasized instance discrimination with large batch sizes and strong augmentations, SimCLR v2 [89] extended this foundation into a full semi-supervised framework. It combines:

- Stronger encoders and augmentations during large-scale contrastive pretraining,

- A deeper projection head with mid-layer fine-tuning to retain invariant features,

- Soft-label distillation to extract value from unlabeled data—even without further label supervision.

These advances allow SimCLR v2 to achieve top-tier performance across both low-label and fully supervised regimes. However, while effective, SimCLR remains a purely instance-level learner, optimizing contrast between individual examples rather than trying to capture the semantic structure of the data manifold directly.

This motivates the next family of methods—ReLIC (REpresentation Learning via Invariant Causal mechanisms)—which extends contrastive learning by incorporating relational and group-level constraints, paving the way for more robust and causally grounded representations.

22.3.8 ReLIC: Representation Learning via Invariant Causal Mechanisms

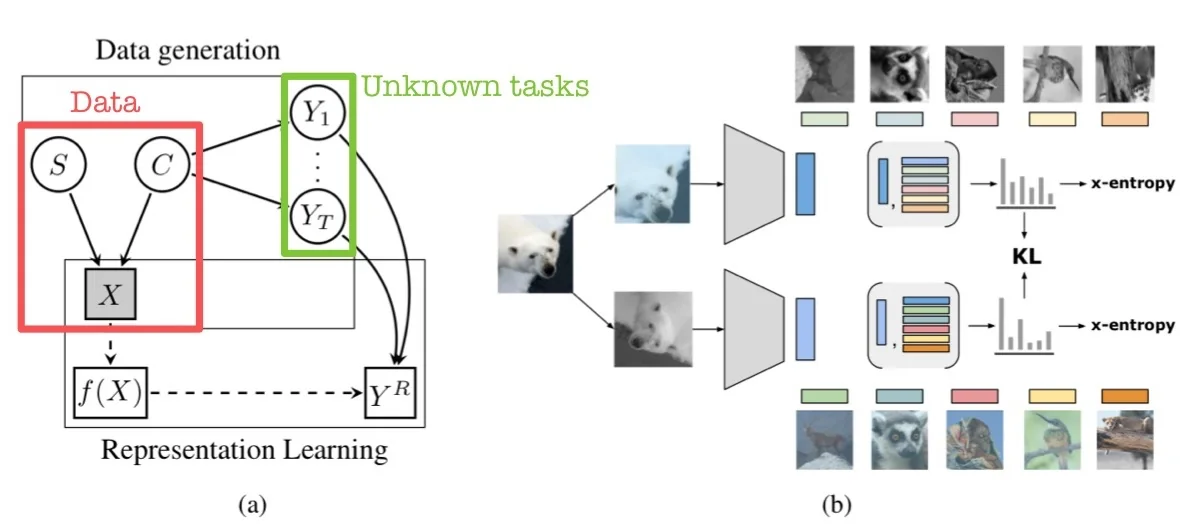

Motivation and Causal Assumptions ReLIC [437] introduces a causal lens to self-supervised representation learning by explicitly aiming to disentangle content from style. The method assumes that each observed image \( X \) is generated by two independent latent factors: \[ X = g(C, S) \] where:

- \( C \) denotes the content—the semantically relevant signal such as object identity, shape, or structure.

- \( S \) represents the style—the nuisance variation such as color, lighting, texture, or viewpoint.

and assumes statistical independence between them: \( C \perp S \). This separation echoes the intuition that the identity of an object (e.g., “cat”) does not depend on superficial visual properties like background or illumination.

To formalize its invariance objective, ReLIC relies on the causal do-calculus [477]. Specifically, for any downstream task \( Y_t \), the model assumes that predictions should be based solely on content \( C \), and remain unchanged under interventions on style \( S \). This is written as: \[ p^{\mathrm {do}(S = s_i)}(Y_t \mid C) = p^{\mathrm {do}(S = s_j)}(Y_t \mid C), \quad \forall s_i, s_j \in \mathcal {S} \] Here, \( p^{\mathrm {do}(S = s)}(Y_t \mid C) \) denotes the interventional distribution—the probability of label \( Y_t \) conditioned on content \( C \), under a hypothetical external intervention that forces the style variable \( S \) to take the value \( s \). The use of do-notation, introduced by Pearl, distinguishes causal effects from observational correlations. In this context, it encodes the notion that the label of an image (e.g., “zebra”) should not change merely because the background shifts from grassland to water, or the lighting changes from day to dusk.

Example: Consider two augmentations of an image of a red car—one where the car appears under daylight and one under shadows. While these views differ in pixel space, the object’s identity is the same. A causally robust model should therefore map both views to the same semantic representation, ignoring the nuisance introduced by style.

In ReLIC, such interventions on \( S \) are simulated using common data augmentations (e.g., random crop, color jitter, Gaussian blur), and the goal becomes to learn a representation \( f(X) \) that reflects \( C \) while being invariant to such augmentations. By explicitly encouraging prediction consistency across different styles, ReLIC aligns representation learning with the causal invariance principle: semantic meaning should remain stable under changes that do not alter the underlying content.

Learning via Invariant Proxy Prediction Since the latent variables \( C \), \( S \), and \( Y_t \) are unobserved during training, ReLIC introduces a self-supervised proxy objective that indirectly enforces the causal invariance principle. Specifically, it defines:

- A proxy task \( Y^R \), instantiated as instance discrimination—distinguishing each image from all others.

- A set of augmentations \( \mathcal {A} = \{a_1, a_2, \dots \} \) that preserve content but vary style. These are treated as interventions on the style variable \( S \).

- A learned encoder \( f(X) \), which is optimized to approximate the latent content variable \( C \).

The central learning principle is that predictions of the proxy task should remain invariant under different style interventions: \[ p^{\mathrm {do}(a_i)}(Y^R \mid f(X)) = p^{\mathrm {do}(a_j)}(Y^R \mid f(X)), \quad \forall a_i, a_j \in \mathcal {A} \] This means that although the augmentations \( a_i, a_j \) may alter stylistic attributes (e.g., color, background), the identity prediction of the image via the proxy task \( Y^R \) should remain unchanged when computed on the representation \( f(X) \).

To implement this, ReLIC defines a joint loss consisting of two components:

- 1.

- A standard contrastive loss (e.g., InfoNCE) that encourages positive pairs to be close and negative pairs to be apart.

- 2.

- An explicit invariance penalty, formalized as a Kullback–Leibler (KL) divergence between the predicted proxy distributions across different augmentations: \[ \mathcal {L}_{\mathrm {inv}} = D_{\mathrm {KL}} \left ( p(Y^R \mid f(a_i(X))) \parallel p(Y^R \mid f(a_j(X))) \right ) \]

The full ReLIC objective is a weighted sum of these terms: \[ \mathcal {L}_{\mathrm {ReLIC}} = \mathcal {L}_{\mathrm {contrastive}} + \beta \cdot \mathcal {L}_{\mathrm {inv}} \] where \( \beta > 0 \) controls the strength of the invariance constraint. This structure ensures that representations are both discriminative and causally invariant, encouraging the encoder \( f(X) \) to capture content while discarding stylistic factors.

Summary ReLIC recasts self-supervised learning as a problem of learning causally invariant representations. Unlike SimCLR or MoCo, which enforce augmentation invariance implicitly through the contrastive loss, ReLIC explicitly penalizes prediction shifts induced by augmentations using a causally inspired KL regularization term. This principled approach leads to features that are not only discriminative but also robust to distributional shifts, improving generalization on downstream tasks and out-of-distribution robustness benchmarks.

From Proxy Tasks to Instance Discrimination To approximate latent content \( C \) without using task-specific labels, ReLIC defines a self-supervised proxy task \( Y^R \) based on instance discrimination. Each training image is treated as its own class: \[ \left \{ (x_i,\, y_i^R = i) \mid x_i \in \mathcal {D} \right \} \] This fine-grained task encourages the model to recognize image instances across views, even when style perturbed. Since it refines any downstream task into its most atomic semantic form, instance discrimination serves as a universal supervision signal for representation learning.

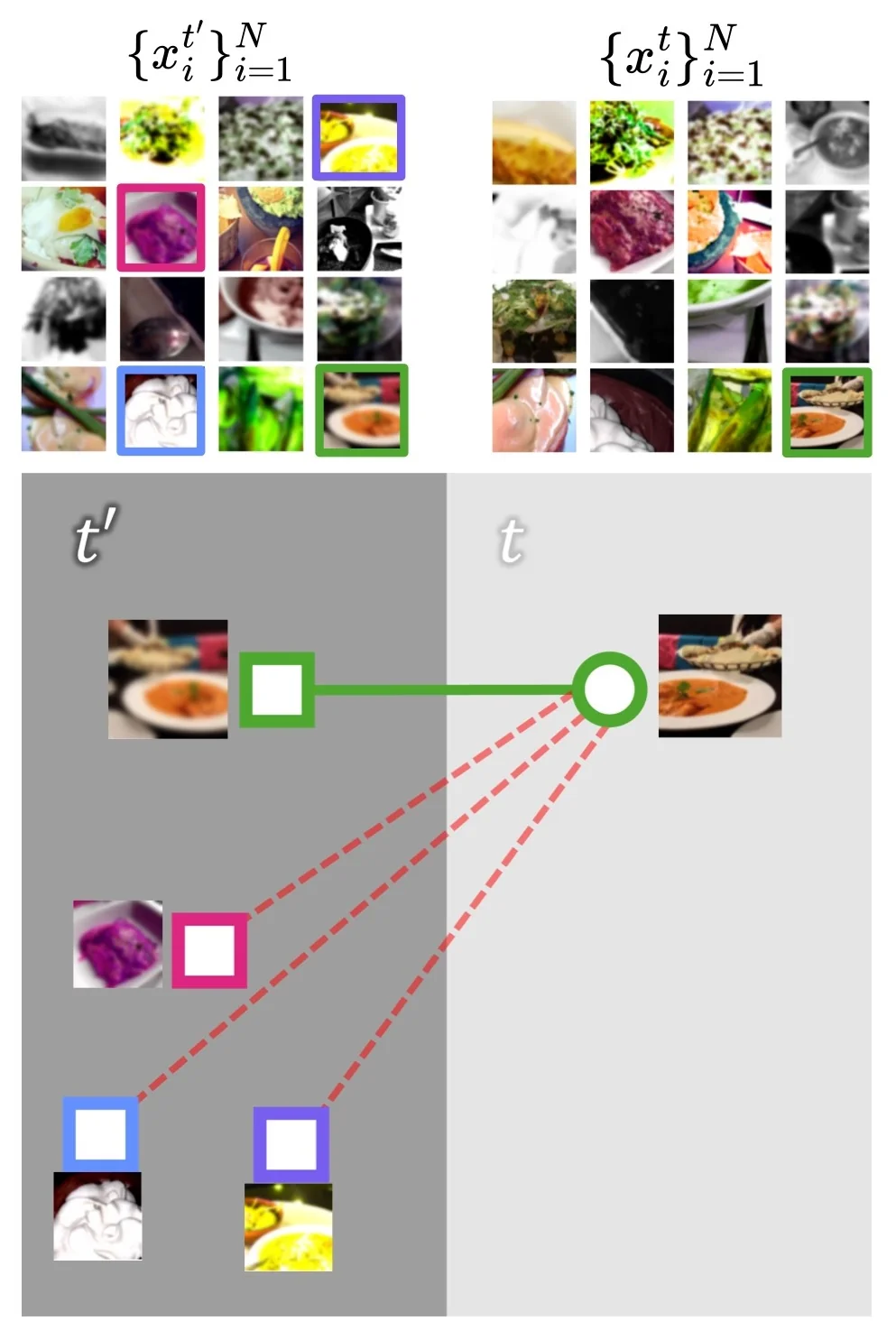

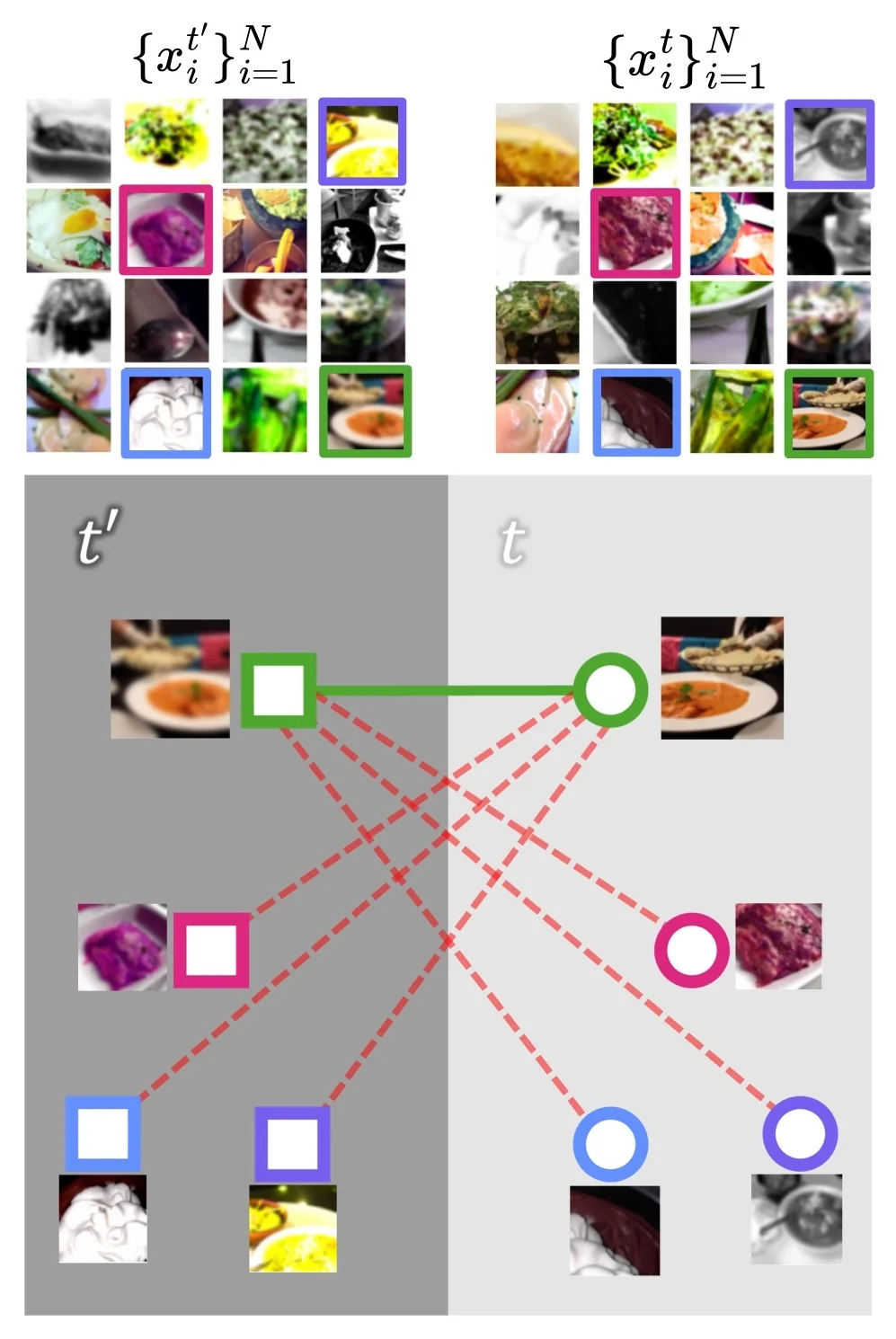

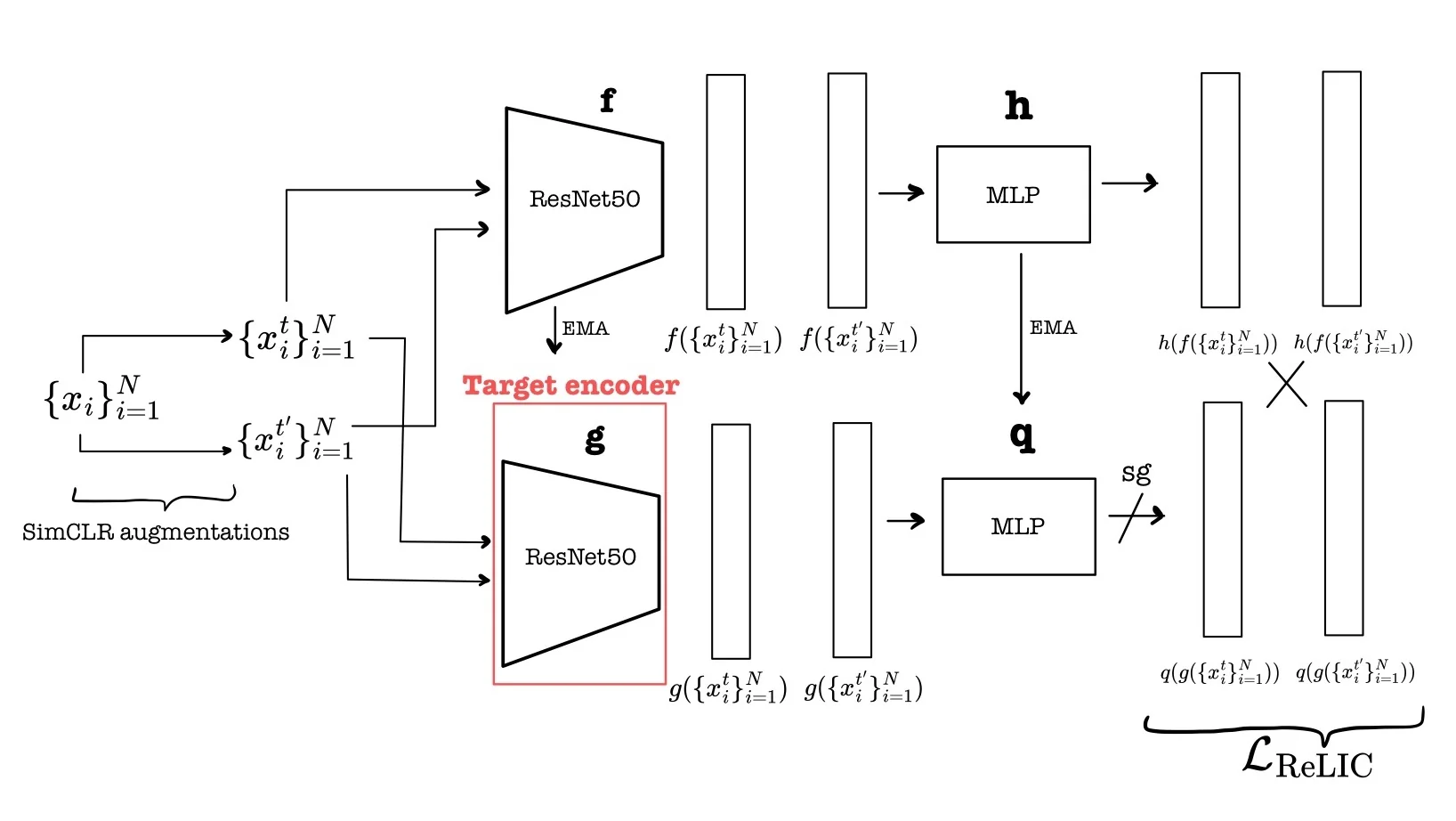

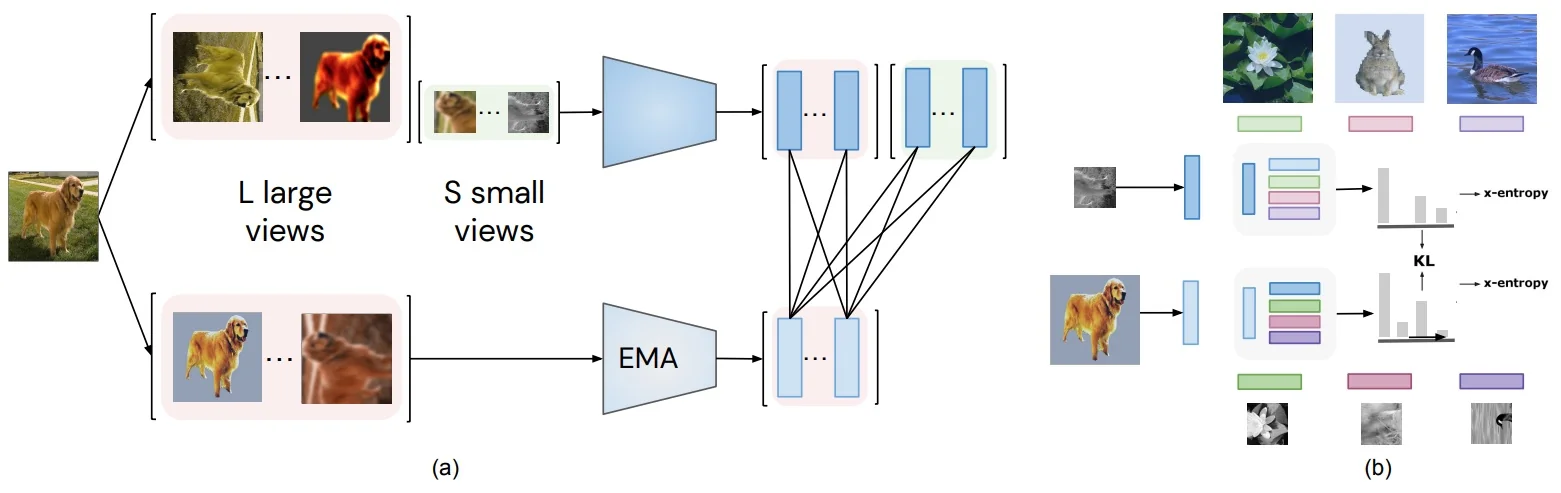

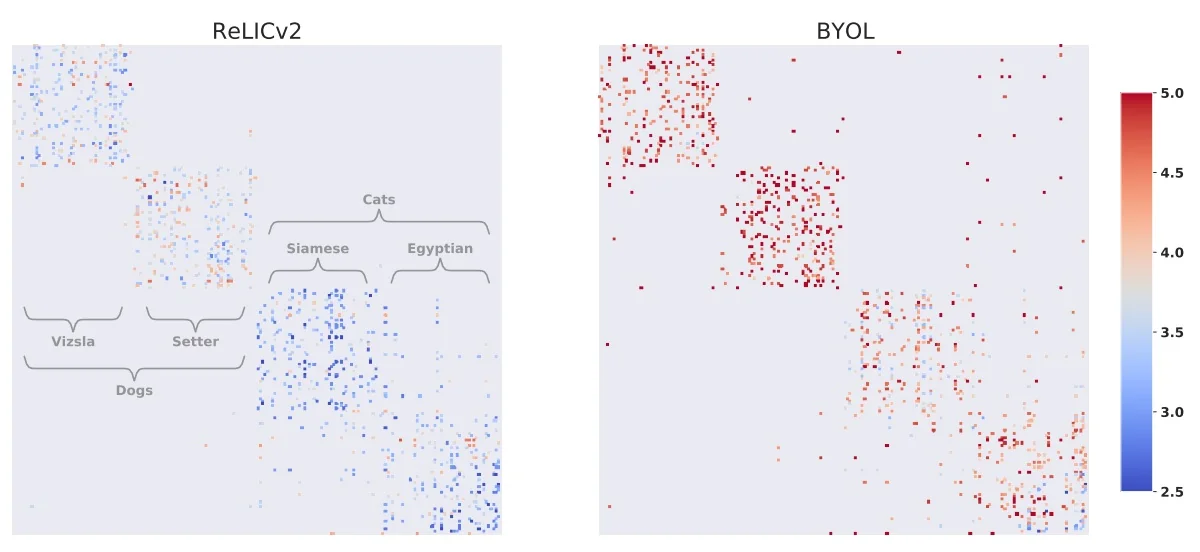

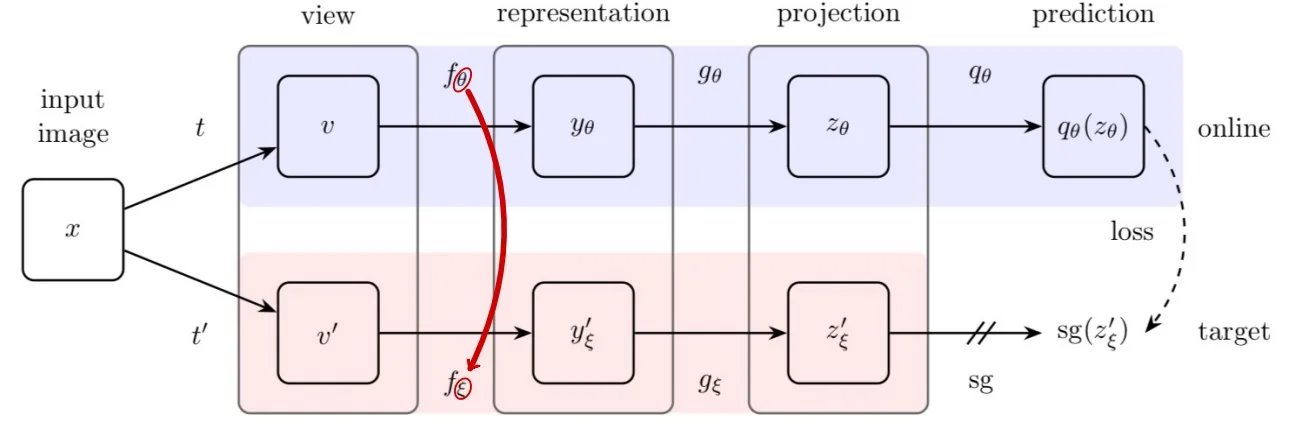

ReLIC Architecture and Training Setup ReLIC employs a dual-view contrastive framework with asymmetric roles for its components. Each image \( x_i \) is augmented twice: \( x_i^t, x_i^{t'} \sim \mathcal {T} \). The two views are processed by:

- \( f \): online encoder, trained via backpropagation.

- \( g \): target encoder, updated as an exponential moving average (EMA) of \( f \): \[ g \leftarrow m \cdot g + (1 - m) \cdot f \]

- \( h, q \): projection heads for \( f \) and \( g \), respectively.

This yields \( \ell _2 \)-normalized embeddings: \[ \mathbf {z}_i^t = h(f(x_i^t)), \qquad \mathbf {z}_i^{t'} = q(g(x_i^{t'})) \]

Terminology note. ReLIC adopts modern functional terminology aligned with self-supervised learning conventions, replacing the classical triplet roles (anchor, positive, negative) with query and target. The online view \( x_i^t \), processed by the trainable encoder \( f \), serves as the query. Its counterpart \( x_i^{t'} \), processed by a fixed encoder \( g \)—either updated via exponential moving average (EMA) or detached via stop-gradient—provides the target. The query is optimized via backpropagation; the target supplies both a matching embedding and a reference similarity distribution. In this formulation, the target view effectively assumes the role of an anchor, acting as a stable reference for both the contrastive (first-order) and distributional (second-order) loss terms.

Contrastive and Distributional Loss Terms The online embedding \( \mathbf {z}_i^t \) serves as a query, contrasted against the batch of target embeddings \( \{\mathbf {z}_j^{t'}\}_{j=1}^N \). ReLIC’s objective includes two components:

- The first term is a contrastive loss, which encourages similarity between a data point \( \mathbf {z}_i^t \) and its positive pair \( \mathbf {z}_i^{t'} \), while contrasting it against all negatives drawn from the other augmented view \( t' \). Importantly, this term is asymmetric: it compares \( \mathbf {z}_i^t \) to the set \( \{\mathbf {z}_j^{t'}\}_{j \ne i} \cup \{\mathbf {z}_i^{t'}\} \), rather than symmetrizing over both directions. However, because both \( t \) and \( t' \) are sampled from a stochastic augmentation distribution, this asymmetry is averaged out across training. This encourages reciprocal distancing of negatives across both views and aligns positive pairs more tightly.

- The second term is a KL divergence regularizer that explicitly enforces distributional invariance. It compares the similarity distributions (i.e., softmax beliefs over all targets) induced by \( \mathbf {z}_i^t \) and \( \mathbf {z}_i^{t'} \) across augmentations. This penalizes shifts in similarity structure due to augmentations, encouraging the model to learn representations where pairwise similarity patterns remain consistent regardless of the applied style transformation. Critically, while the loss is often written using shorthand as \( p(\mathbf {z}_i^t) \) and \( p(\mathbf {z}_i^{t'}) \), these distributions are coupled—each depends on the cross-view similarities and cannot be computed independently. This coupling is what gives the KL term its invariance-enforcing power.

Together, these losses promote both instance-level alignment and global relational consistency across views—key to ReLIC’s causal invariance principle.

The use of a target encoder updated via EMA plays a central role in enabling these two losses to work in tandem. While the contrastive objective focuses on instance discrimination, the invariance loss compares entire distributions of similarity scores. In this setup, the online encoder must align its outputs with a stable reference. By slowly updating the target encoder as an exponential moving average of the online encoder, ReLIC ensures that the embeddings used to construct the target distributions evolve smoothly over time.

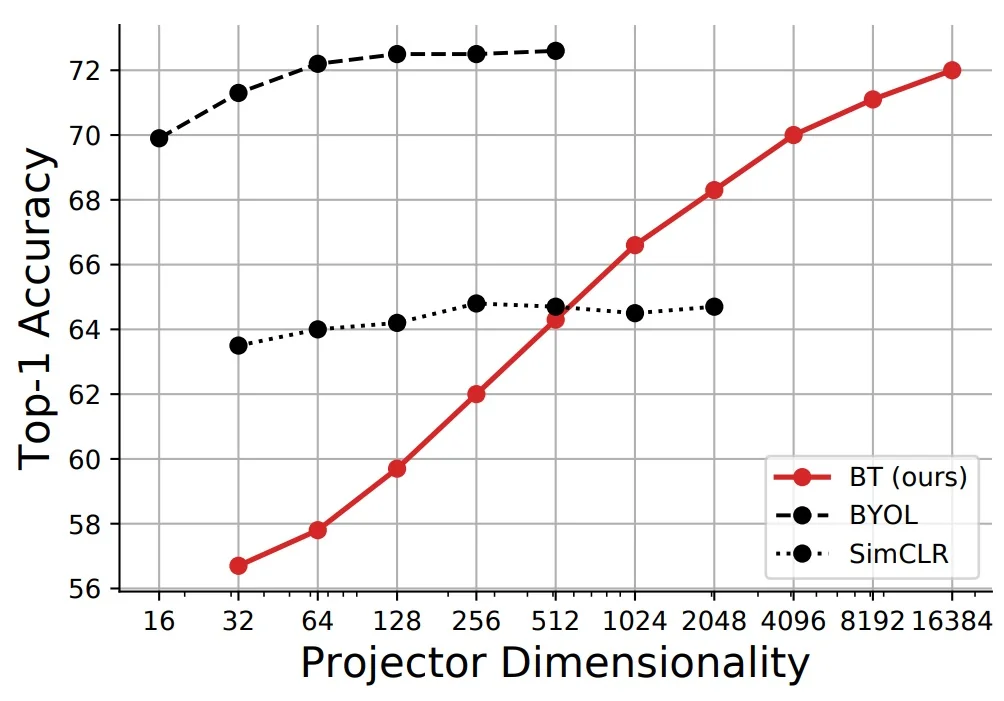

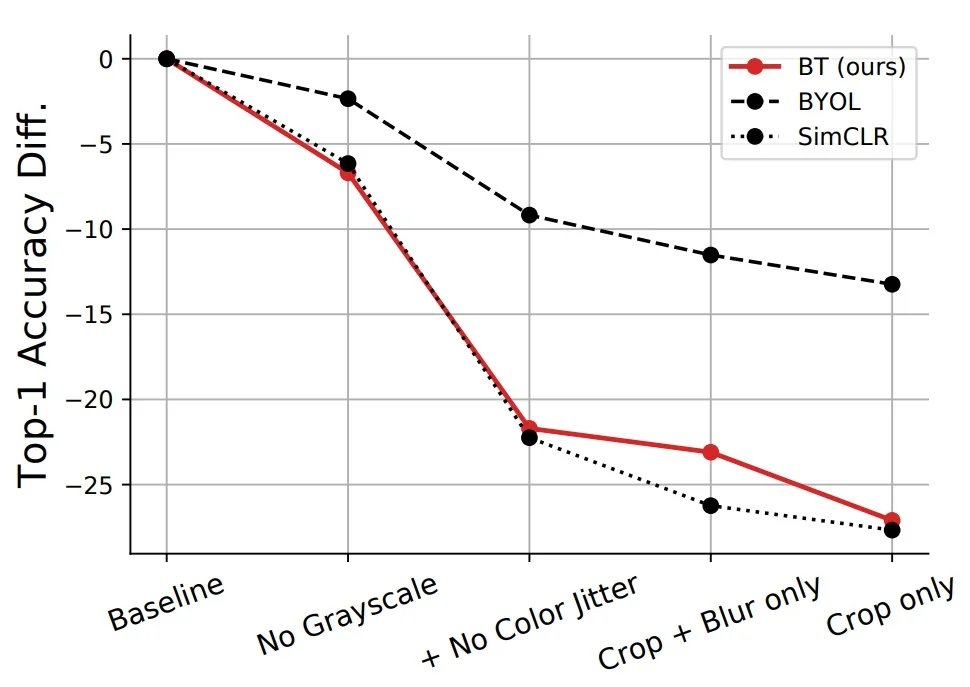

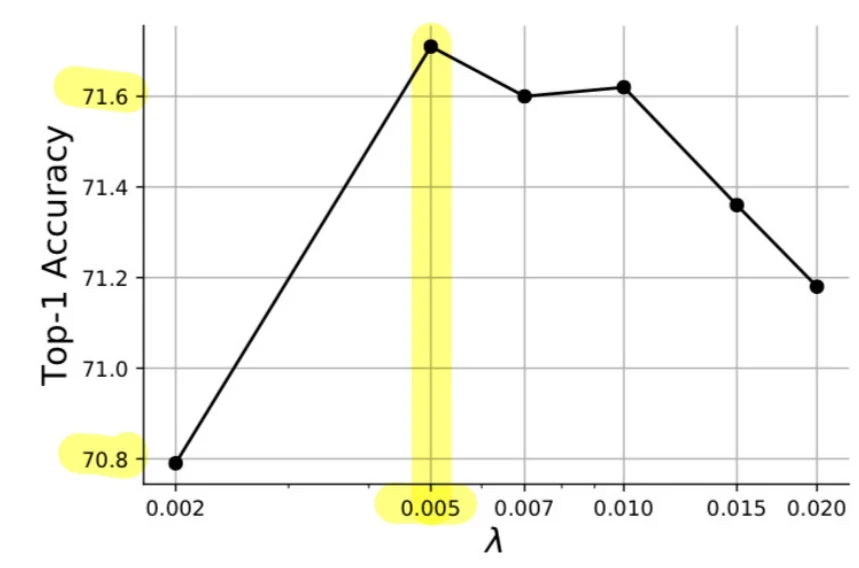

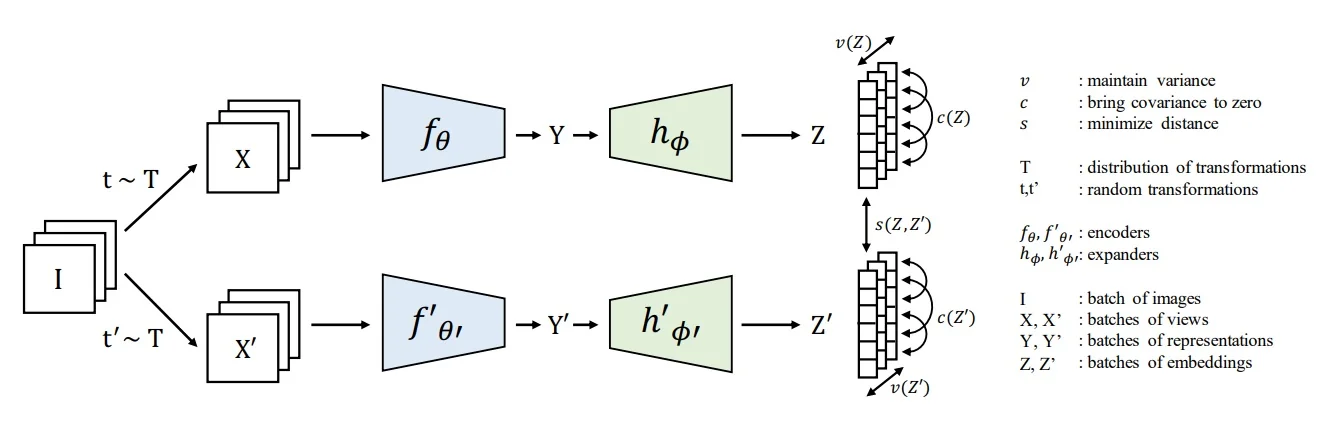

This strategy is adapted from BYOL [188] and is crucial for preventing representational collapse and instability in optimization. Unlike MoCo [211], which uses EMA to maintain a large and consistent dictionary of negatives, ReLIC leverages it to stabilize relational signals—specifically, the structure of similarities across samples and augmentations. The EMA target acts as a form of temporal ensembling, allowing the online network to chase a slowly moving target that encodes more robust, invariant relationships.