Lecture 11: CNN Architectures II

11.1 Post-ResNet Architectures

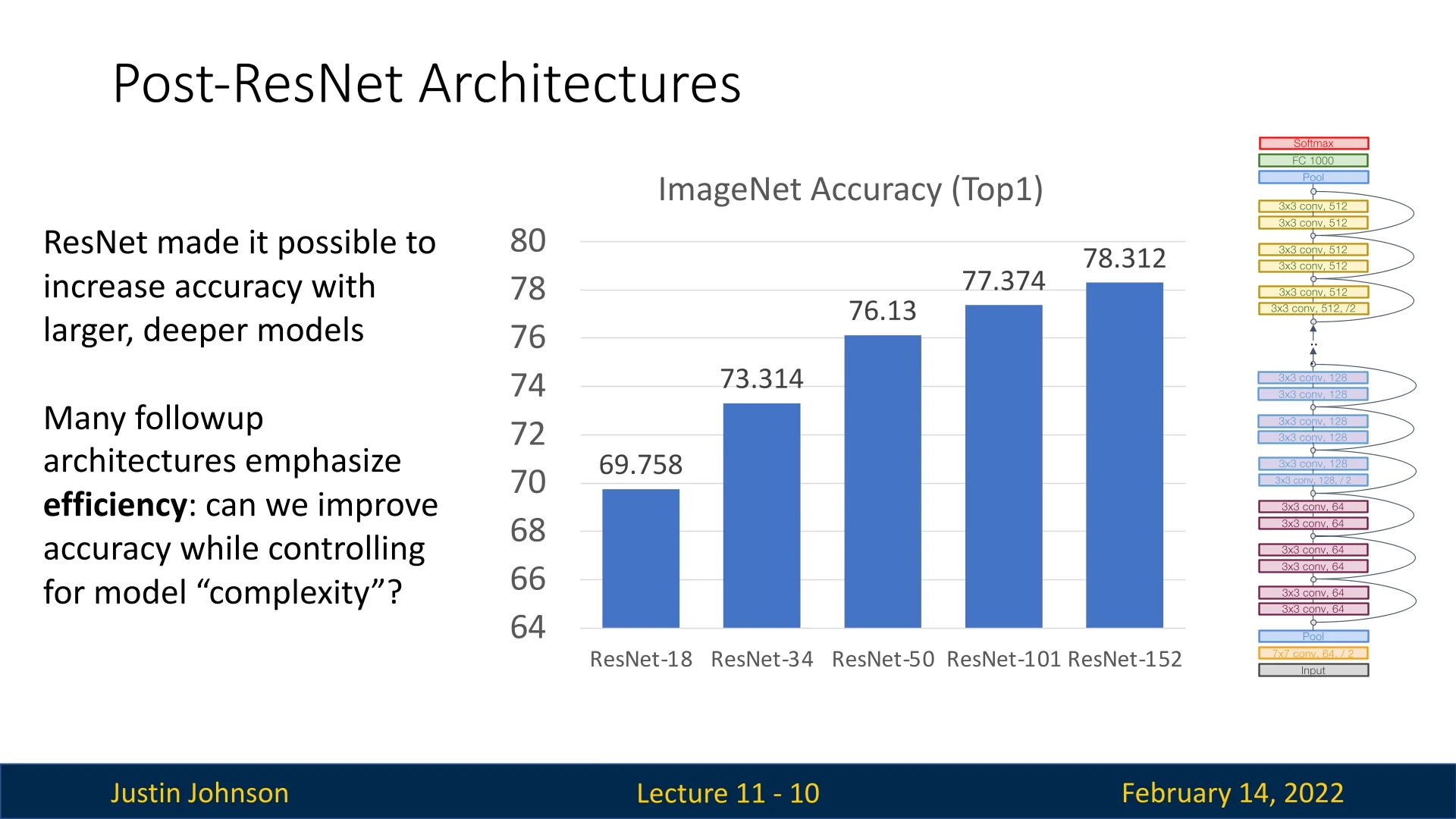

ResNet revolutionized deep learning by making it feasible to train much deeper models while maintaining high accuracy. However, increasing the depth indefinitely is not always practical due to computational constraints. Many subsequent architectures aim to improve accuracy while optimizing for computational efficiency. The goal is to maintain or surpass ResNet’s performance while controlling model complexity.

Model complexity can be measured in several ways:

- 1.

- Number of Parameters: The total number of learnable parameters in the model.

- 2.

- Floating Point Operations (FLOPs): The number of arithmetic

operations required for a single forward pass. This metric has subtle

nuances:

- Some papers count only operations in convolutional layers and ignore activation functions, pooling, and Batch Normalization.

- Many sources, including Justin’s notation, define “1 FLOP” as “1 multiply and 1 addition.” Thus, a dot product of two \(N\)-dimensional vectors requires \(N\) FLOPs.

- Other sources, such as NVIDIA, define a multiply-accumulate (MAC) operation as 2 FLOPs, meaning a dot product of two \(N\)-dimensional vectors takes \(2N\) FLOPs.

- 3.

- Network Runtime: The actual time taken to perform a forward pass on real hardware.

11.2 Grouped Convolutions

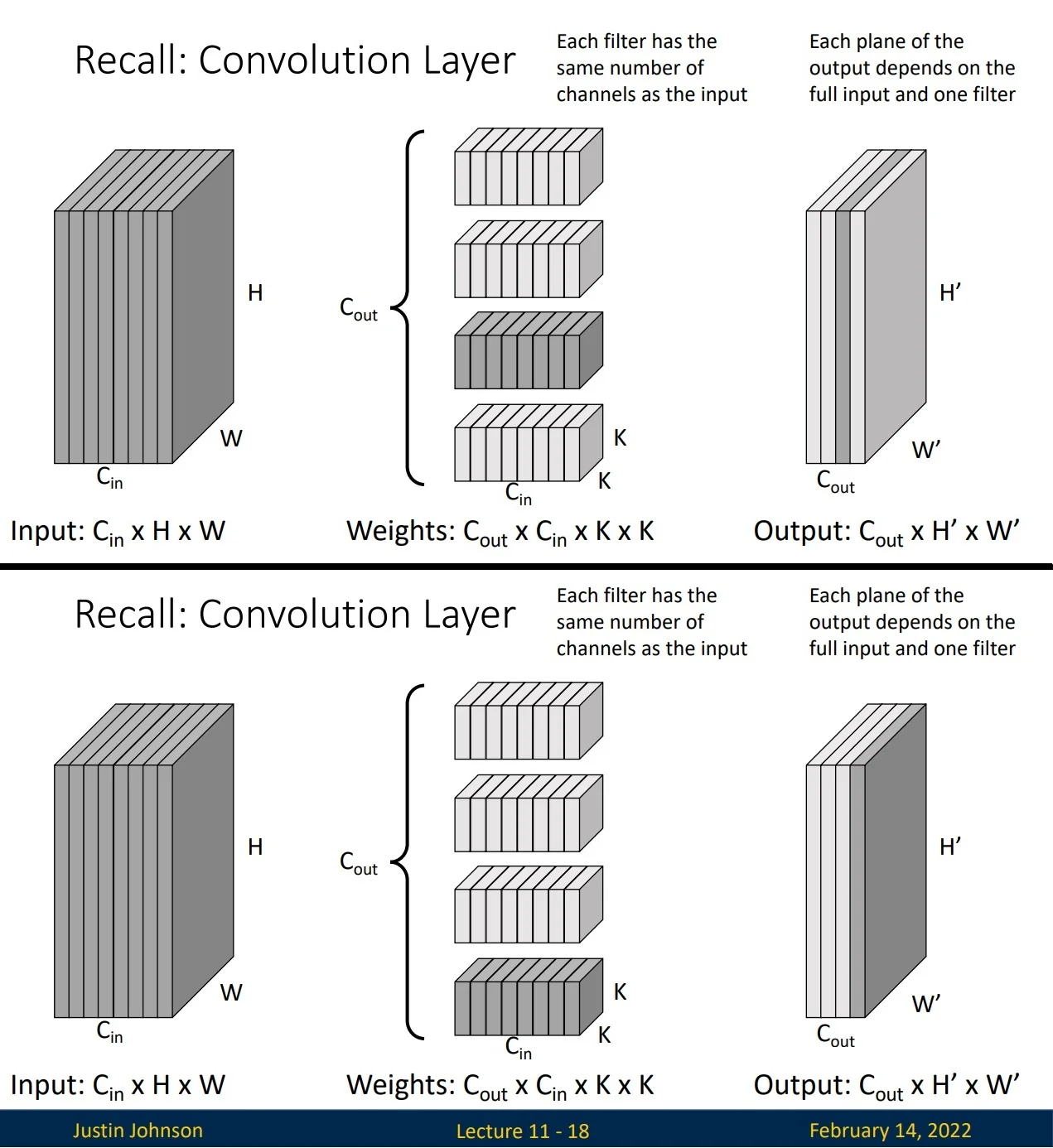

Before introducing grouped convolutions, let us recall the structure of standard convolutions. In a conventional convolutional layer:

- Each filter has the same number of channels as the input.

- Each plane of the output depends on the entire input and one filter.

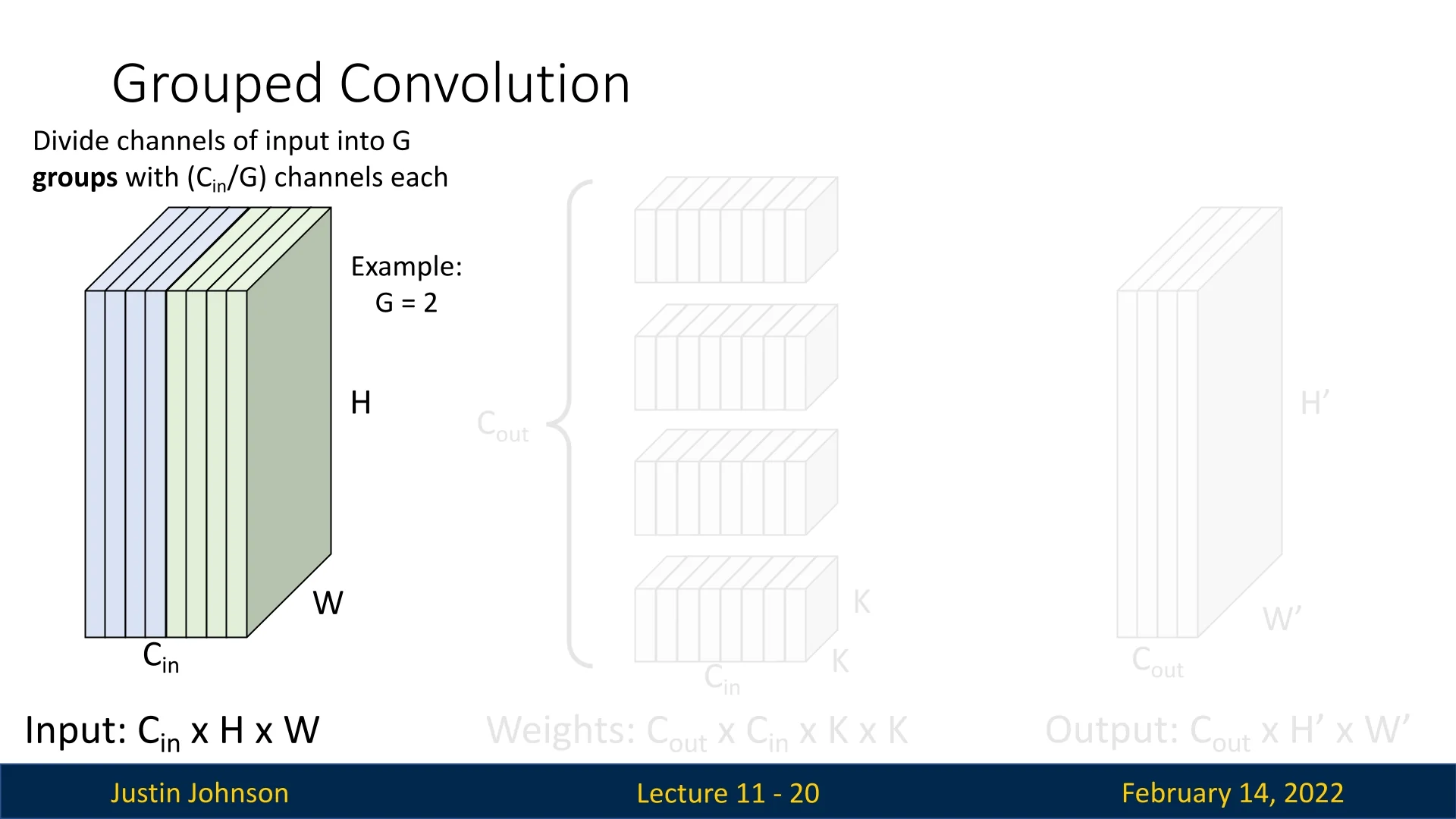

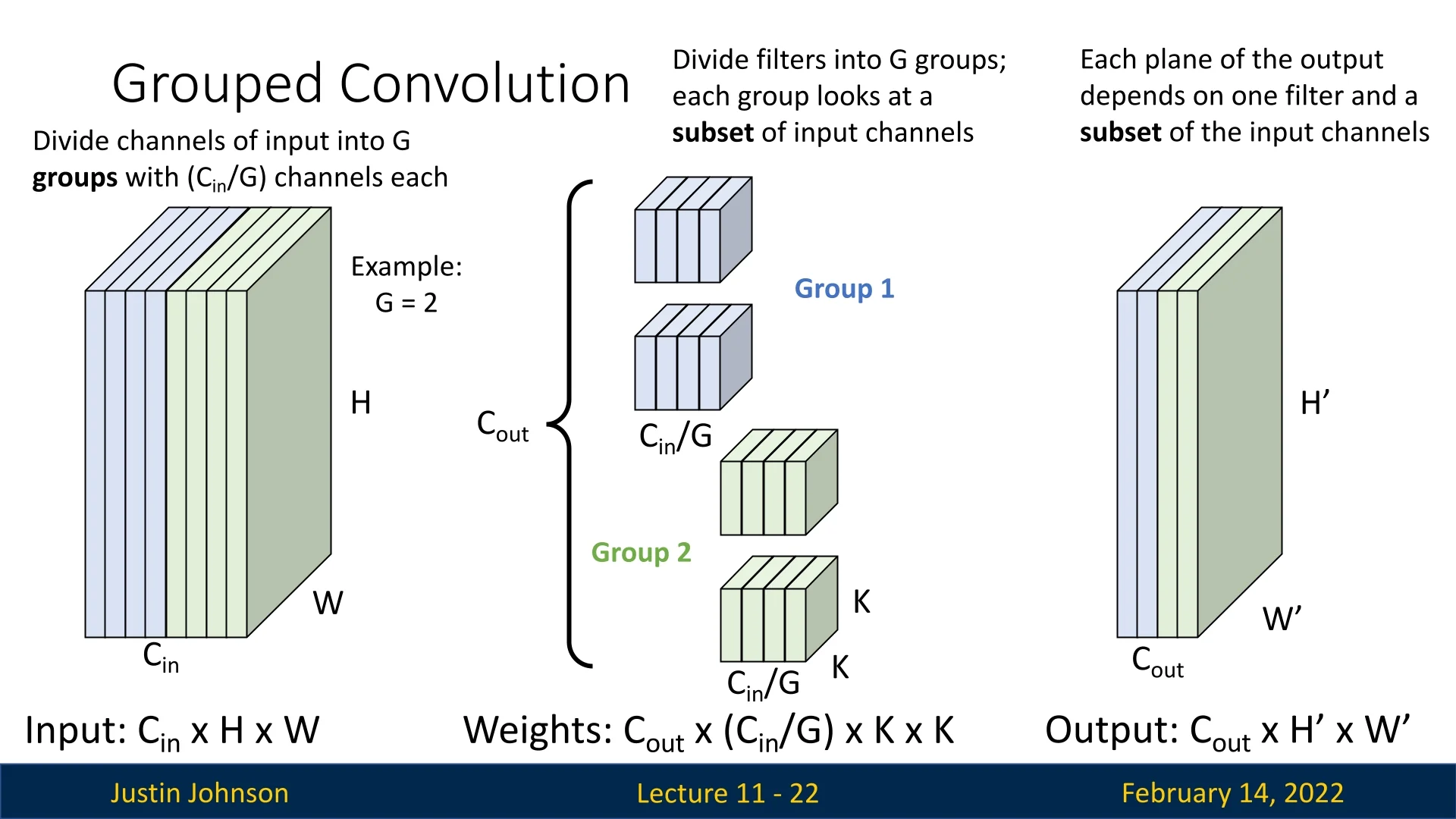

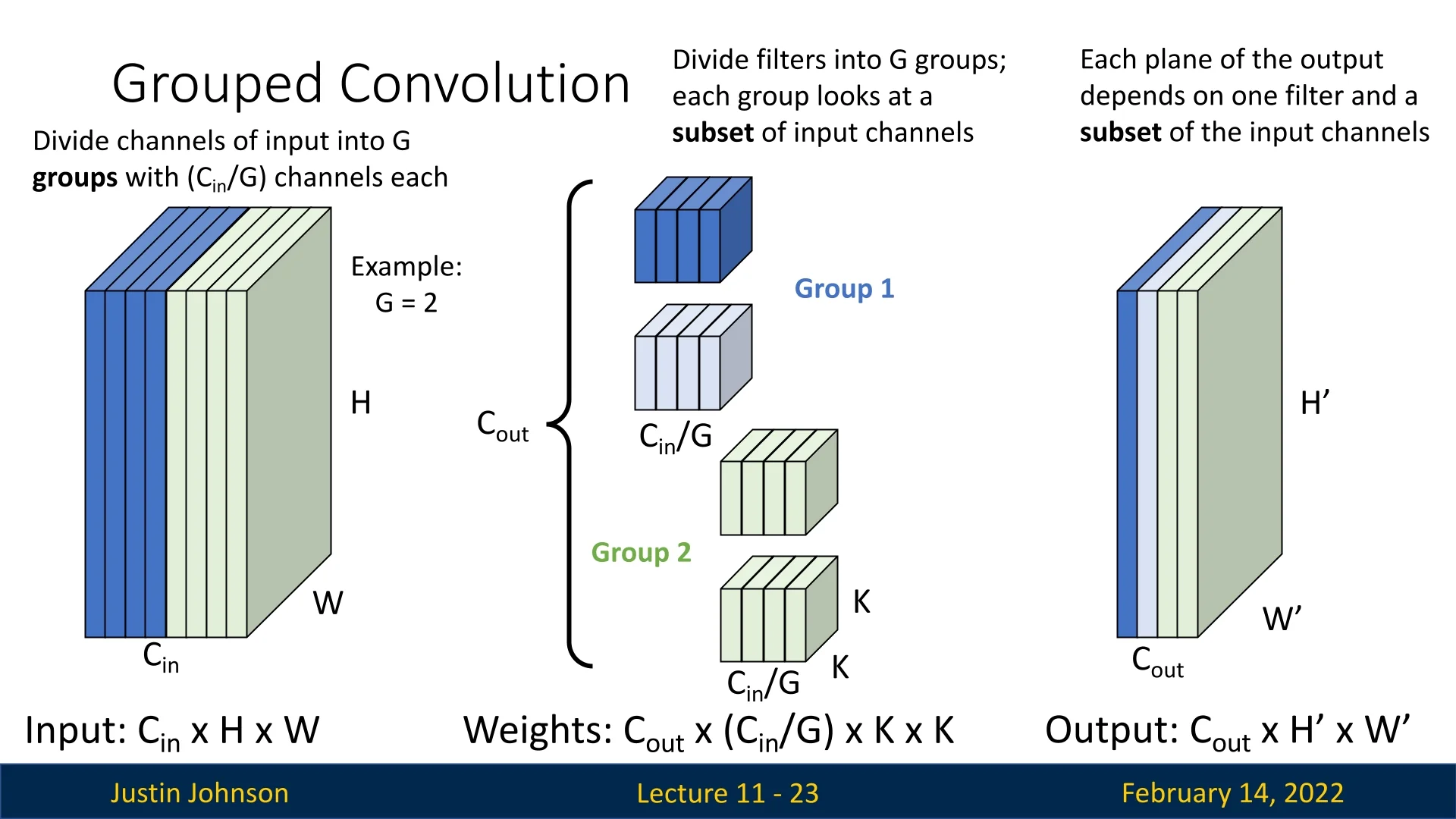

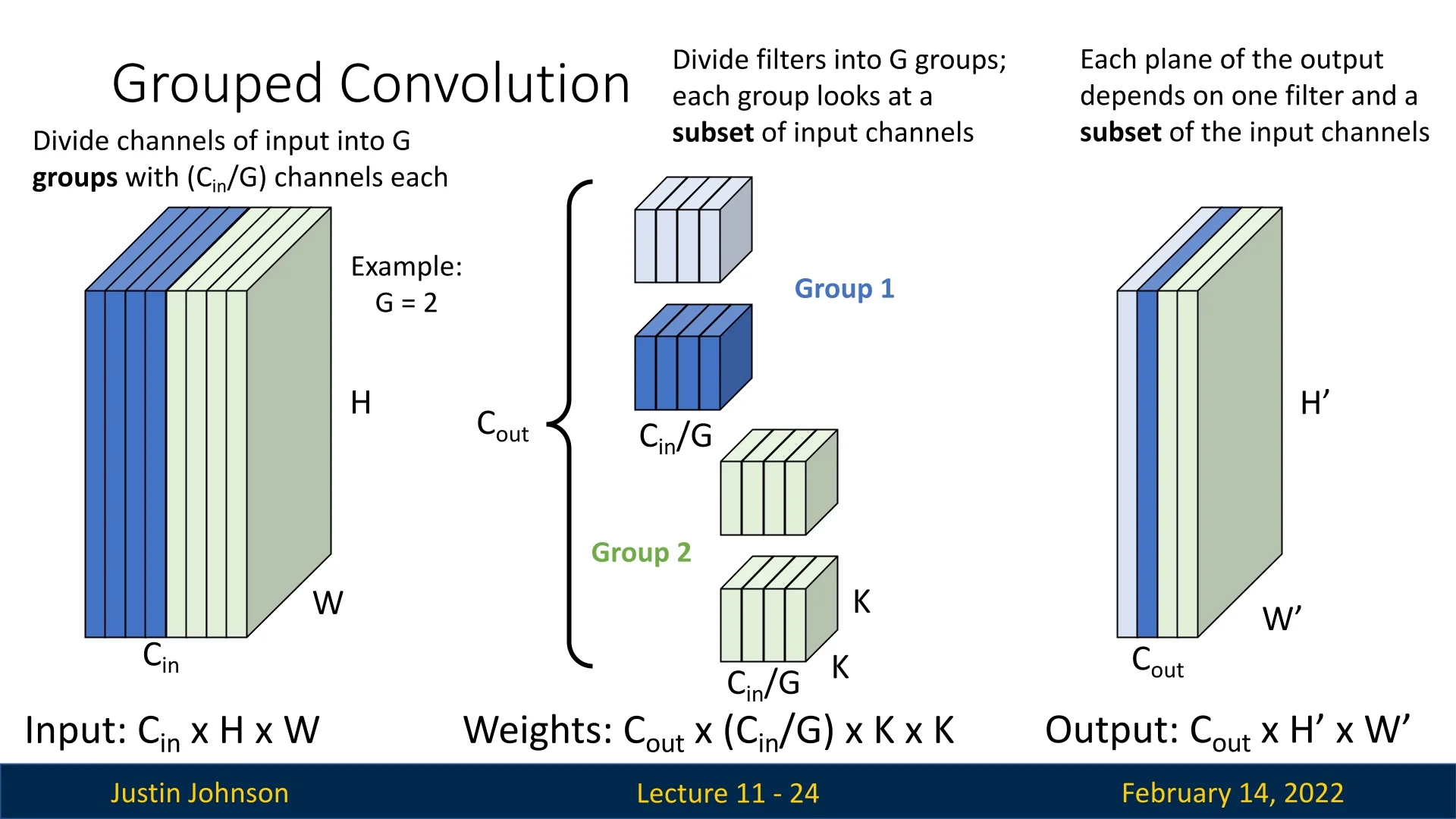

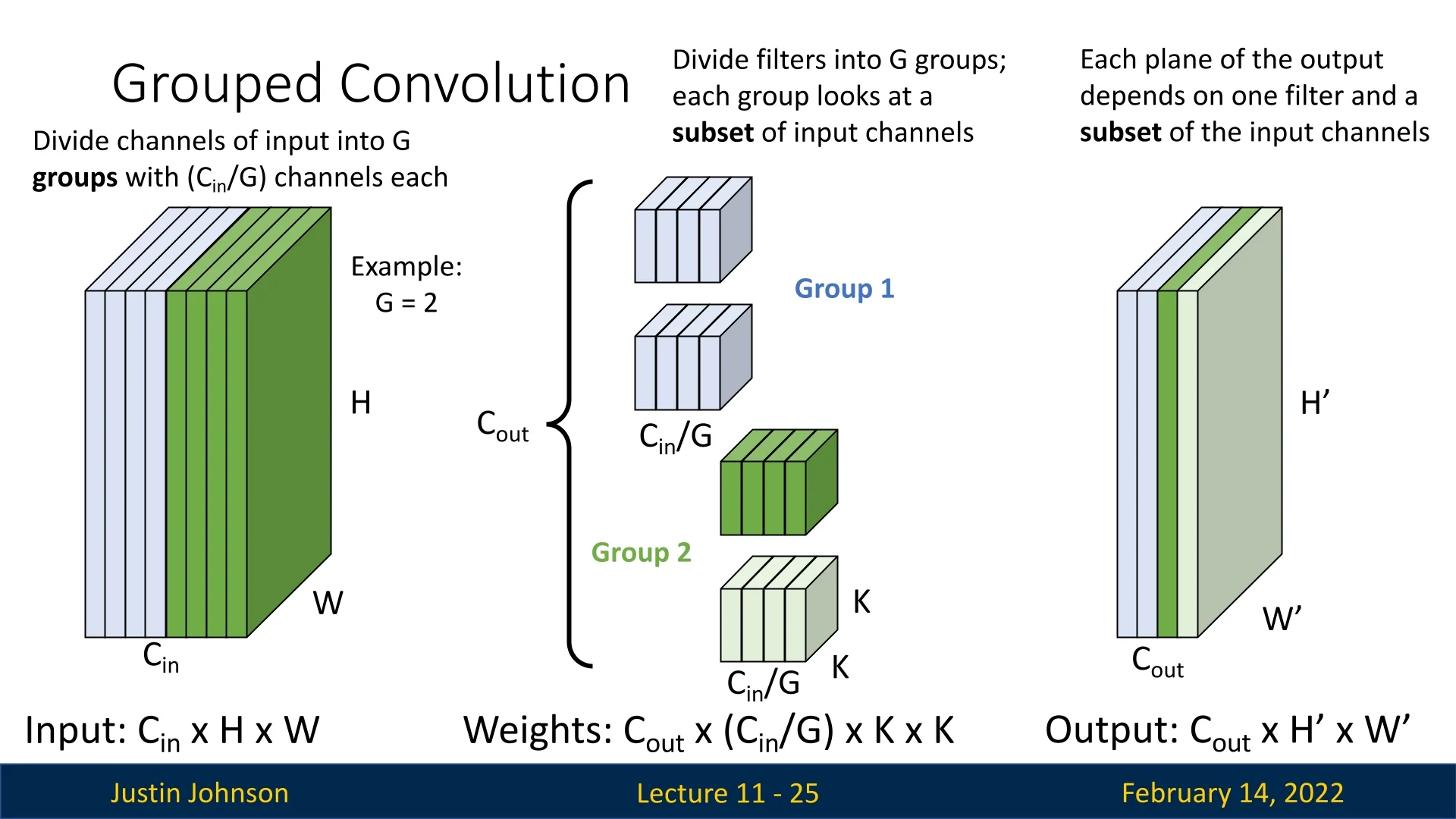

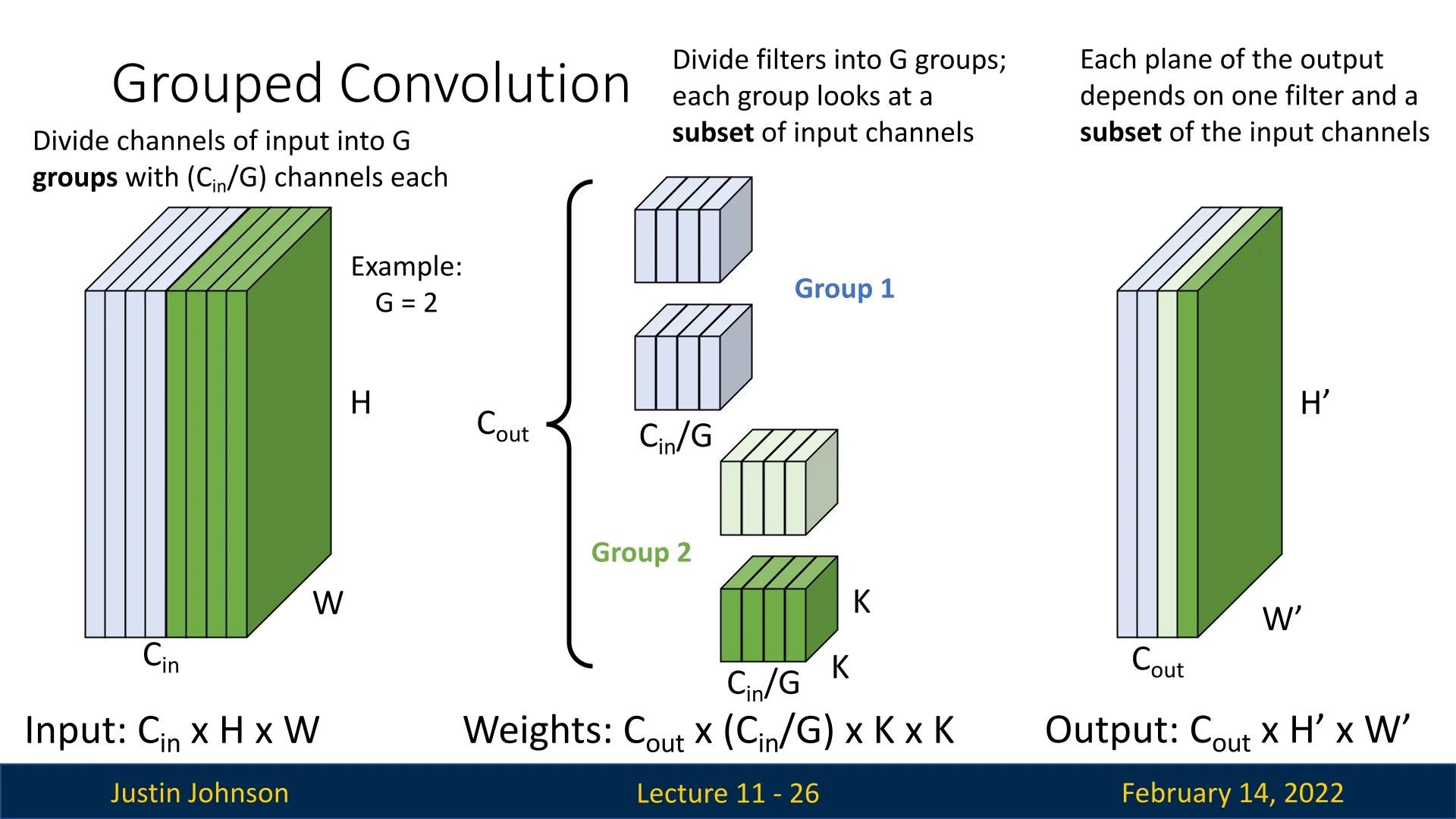

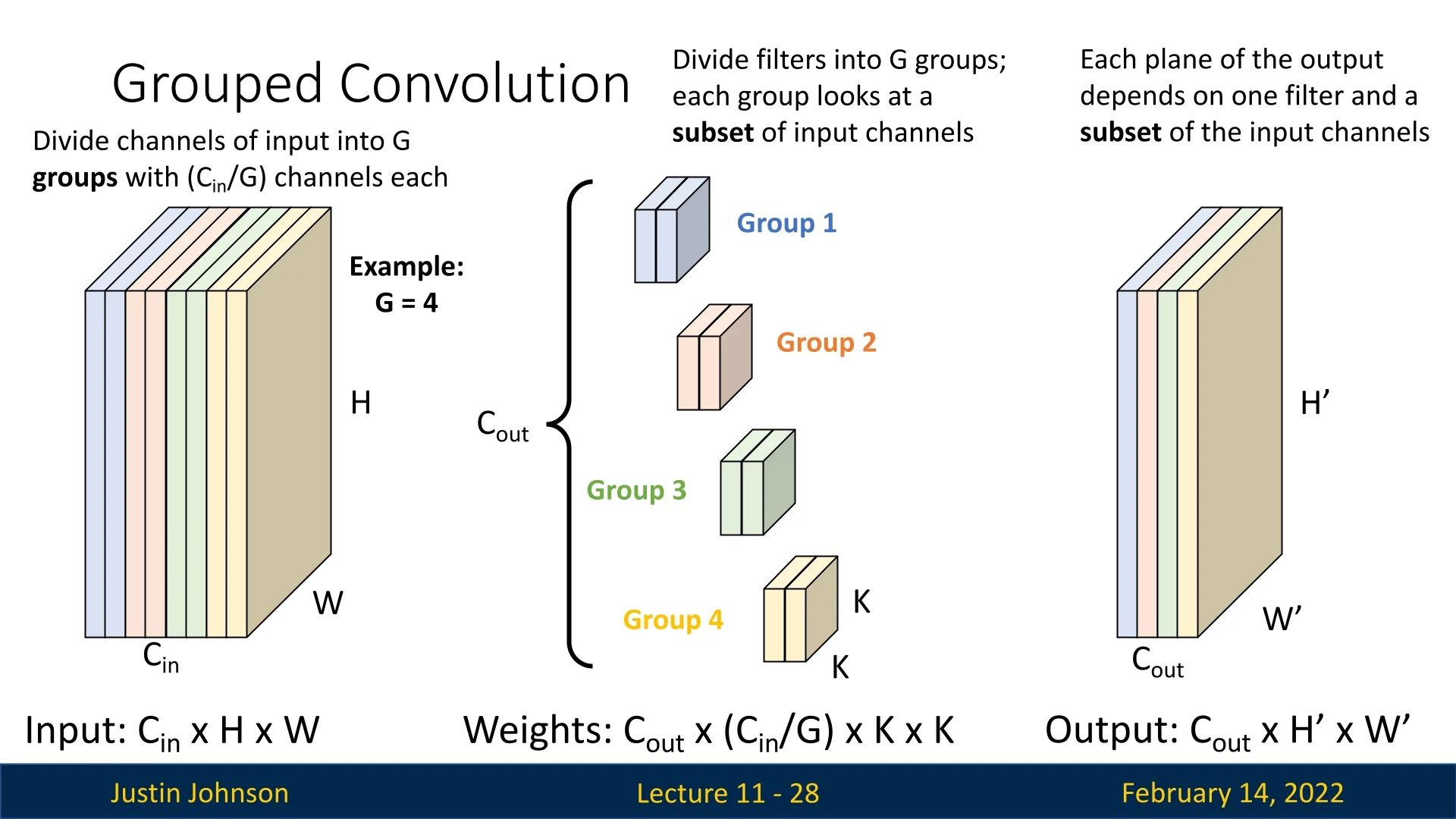

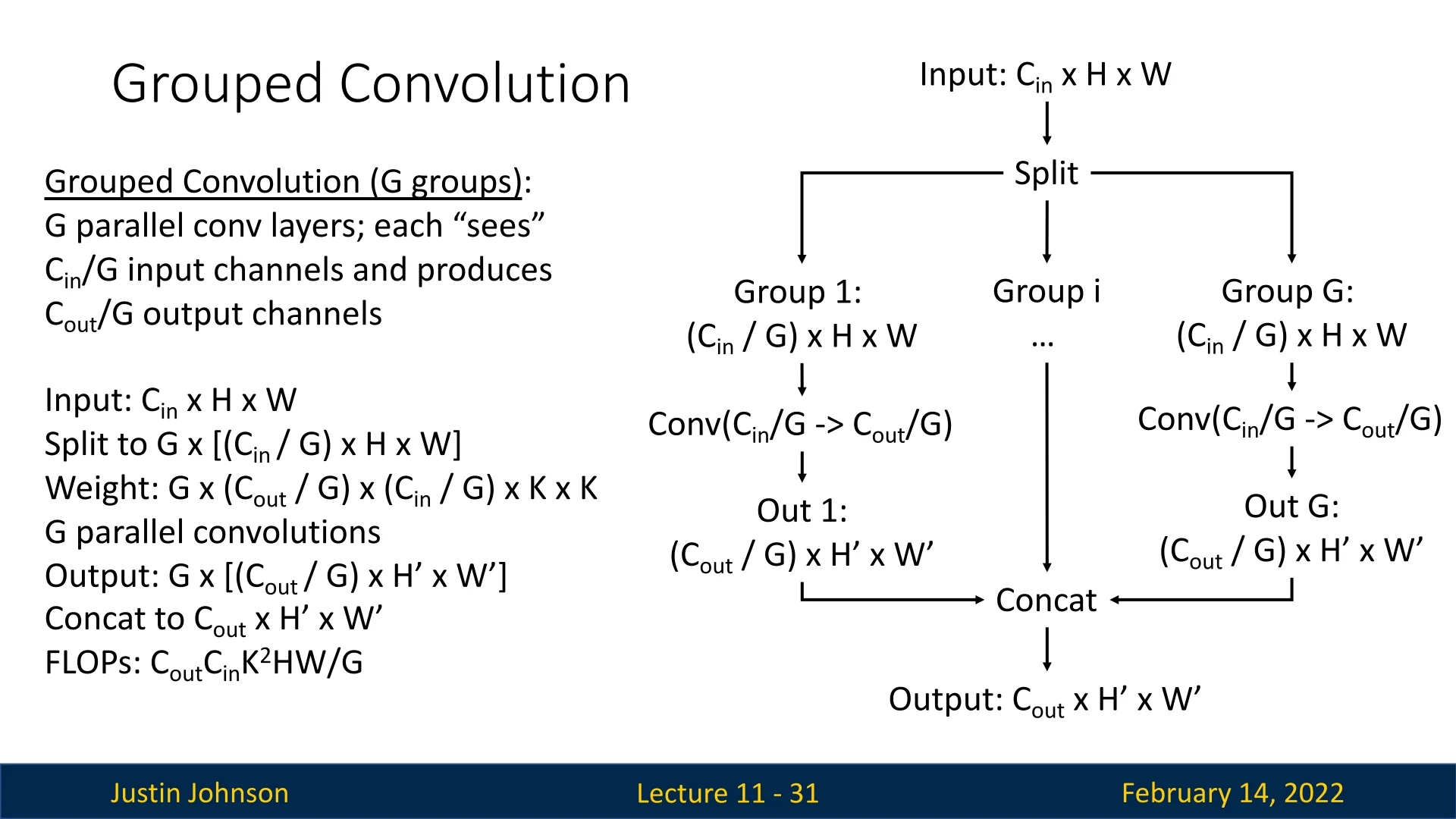

In grouped convolutions, we divide the input channels into \(G\) groups, where \(G\) is a hyperparameter. Each group consists of \(C_{in} / G\) channels.

- Each filter only operates on a specific subset of input channels corresponding to its group.

- The filters are divided into \(G\) groups, similar to input channels.

- The resulting weight tensor has dimensions: \(C_{out} \times (C_{in}/G) \times K \times K\).

Each output feature map now depends only on a subset of the input channels. Each group of filters produces \(C_{out}/G\) output channels.

We can visualize the process step by step:

This concept generalizes for any \(G > 1\). Below is an example where \(G=4\):

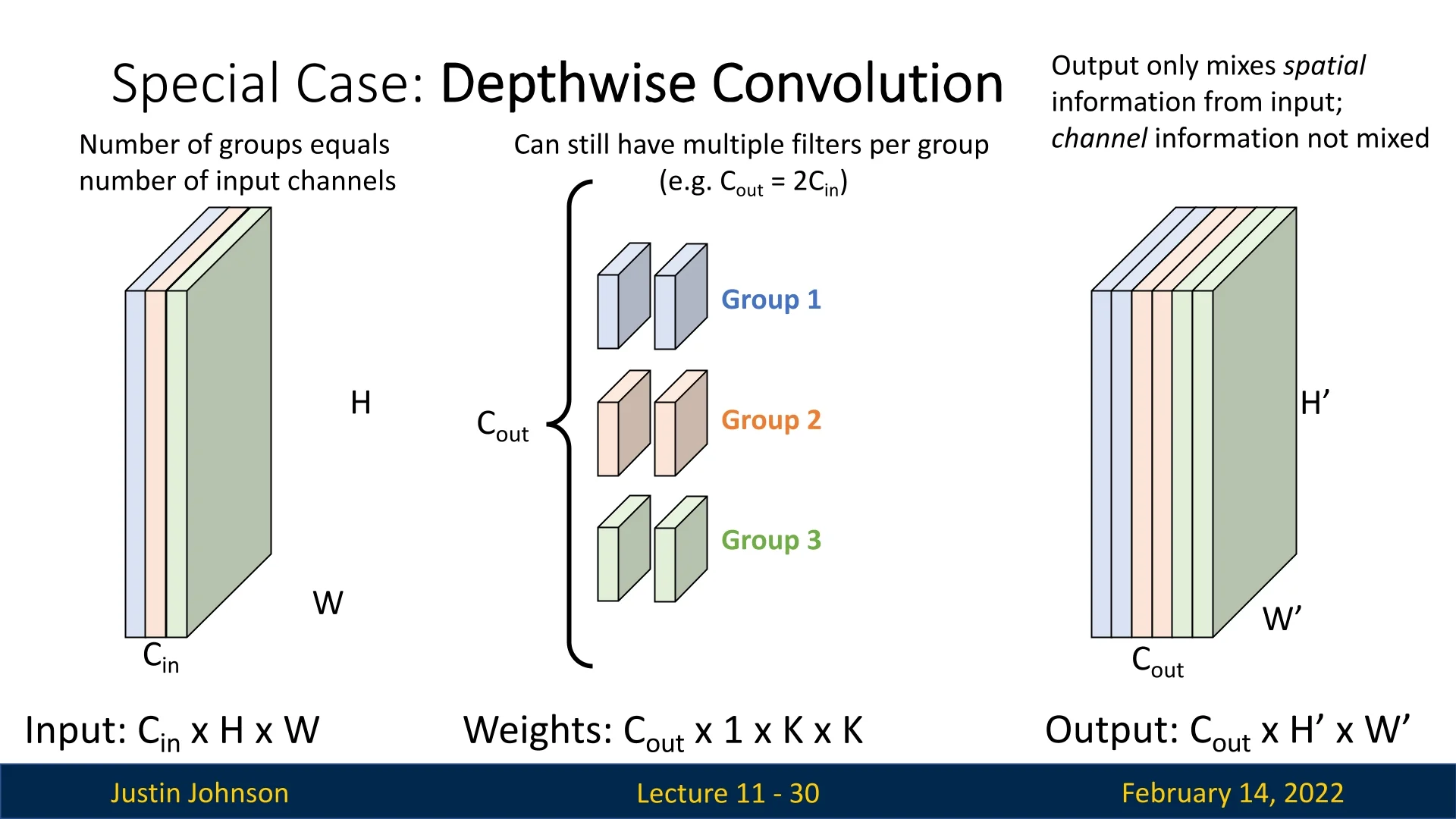

A special case of grouped convolutions that we’ve already encountered is depthwise convolution, where \(G\) is set to be equal to the number of input channels. In this scenario:

- Each filter operates on only one input channel.

- Output feature maps only mix spatial information but do not mix channel information.

Using grouped convolutions significantly reduces computational cost, making them an effective tool for designing efficient deep learning models.

11.2.1 Grouped Convolutions in PyTorch

Grouped convolutions can be efficiently implemented in PyTorch using the groups parameter in torch.nn.Conv2d. By default, groups=1, which corresponds to standard convolution where each filter processes all input channels. Setting groups > 1 splits the input channels into \(G\) groups, each processed by independent convolutional filters.

Below is an example demonstrating how to define grouped convolutions in PyTorch:

import torch

import torch.nn as nn

# Standard convolution (groups=1)

conv_standard = nn.Conv2d(in_channels=64, out_channels=128, kernel_size=3, padding=1, groups=1)

# Grouped convolution with G=2 (splitting input into 2 groups)

conv_grouped = nn.Conv2d(in_channels=64, out_channels=128, kernel_size=3, padding=1, groups=2)

# Depthwise convolution (each input channel has its own filter)

conv_depthwise = nn.Conv2d(in_channels=64, out_channels=64, kernel_size=3, padding=1, groups=64)

# Forward pass with a random input tensor

x = torch.randn(1, 64, 224, 224) # Batch size of 1, 64 input channels, 224x224 image

output_standard = conv_standard(x)

output_grouped = conv_grouped(x)

output_depthwise = conv_depthwise(x)

print(f"Standard Convolution Output Shape: {output_standard.shape}")

print(f"Grouped Convolution Output Shape: {output_grouped.shape}")

print(f"Depthwise Convolution Output Shape: {output_depthwise.shape}")Running this code will produce the following output:

Standard Convolution Output Shape: torch.Size([1, 128, 224, 224])

Grouped Convolution Output Shape: torch.Size([1, 128, 224, 224])

Depthwise Convolution Output Shape: torch.Size([1, 64, 224, 224])Key Observations

-

Standard Convolution (\(groups=1\)):

- Each filter operates across all input channels.

- Computational cost remains high.

- The output has 128 channels, same as the number of filters.

-

Grouped Convolution (\(groups=G\)):

- The input channels are divided into \(G\) groups, with each group processed by independent filters.

- Computational cost is reduced by a factor of \(G\), making it more efficient.

- The output still has 128 channels, despite reducing computation.

-

Depthwise Convolution (\(groups=C_{in}\)):

- Each input channel has its own dedicated filter.

- Spatial information is mixed, but channel-wise information is not combined.

- The output has the same number of channels as the input (\(C_{in} = C_{out}\)).

When to Use Grouped Convolutions?

- Efficient Model Architectures: Used in models such as ResNeXt and Xception, to balance computational cost and accuracy.

- Reducing Computation in Large Networks: Splitting channels into groups significantly reduces FLOPs, making inference faster.

- Specialized Feature Learning: Each group can learn specialized features independently, improving representation learning.

Grouped convolutions, especially when combined with bottleneck layers and pointwise convolutions, allow for high-performance networks with significantly reduced computational costs.

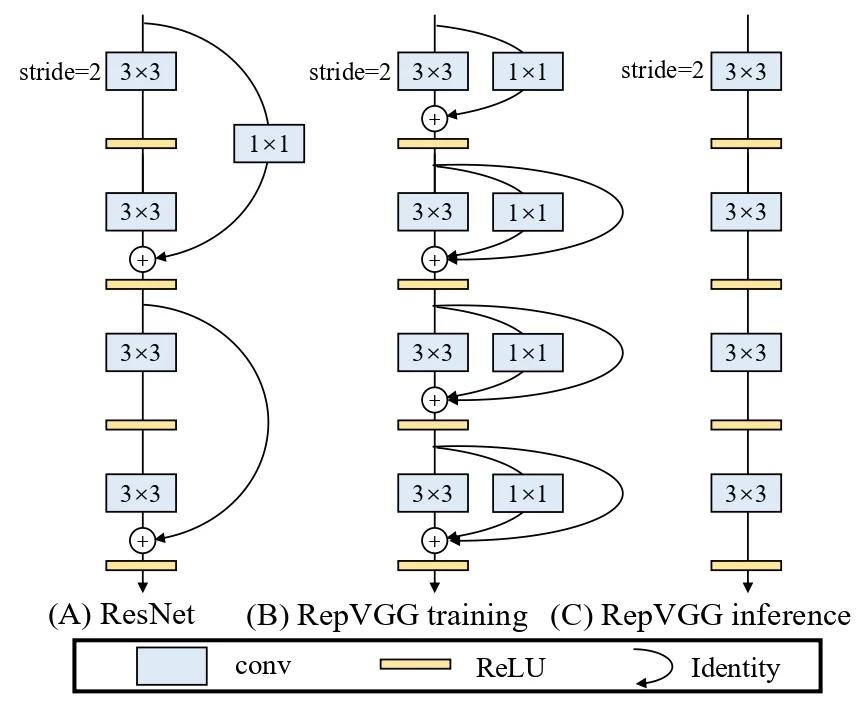

11.3 ResNeXt: Next-Generation Residual Networks

ResNeXt, introduced by Microsoft Research in 2017 [708], builds upon ResNet’s foundation by incorporating aggregated residual transformations, utilizing multiple parallel pathways within residual blocks. This approach improves accuracy while maintaining computational efficiency, making it a more scalable and flexible architecture.

11.3.1 Motivation: Why ResNeXt?

Despite the success of ResNet, deeper and wider networks come with increased computational costs. Simply increasing depth does not always yield better performance due to optimization challenges, diminishing returns, and increased memory requirements. While widening the network (increasing the number of channels per layer) can improve capacity, it significantly increases FLOPs, making the model inefficient.

ResNeXt introduces a third dimension, cardinality (\(G\)), which refers to the number of parallel pathways in a residual block. Instead of solely increasing depth or width, ResNeXt adds multiple transformation pathways within a single block. The results are then concatenated together to a single output for the block. This allows for higher representational power without increasing the number of FLOPs, hence, without greatly increasing the computational cost.

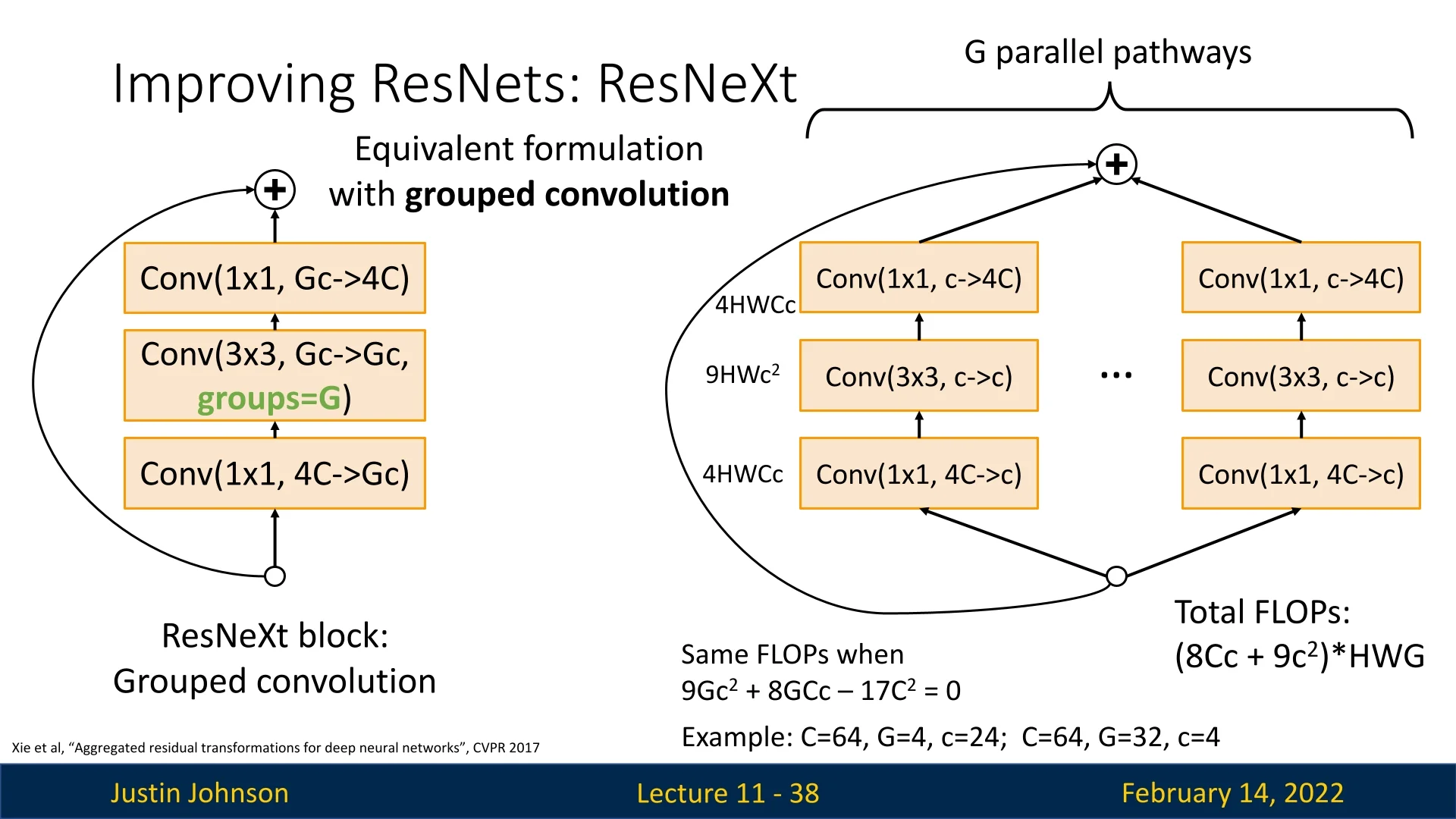

11.3.2 Key Innovation: Aggregated Transformations

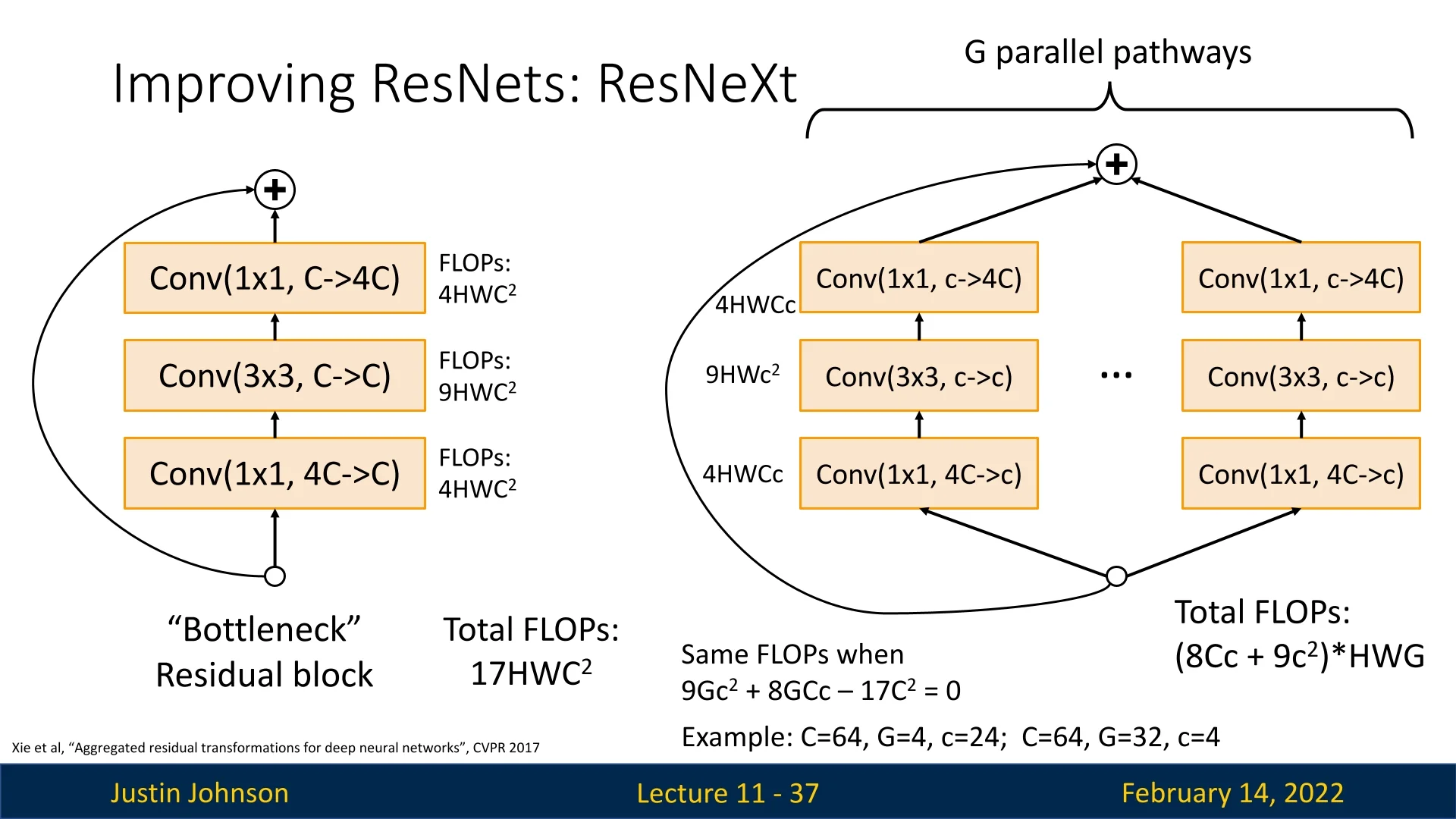

The key innovation in ResNeXt is the use of G parallel pathways of residual transformations. The original bottleneck block in ResNet consists of:

- A \(1\times 1\) convolution to reduce dimensionality (\(4C \to C\)), costing \(4HWC^2\) FLOPs.

- A \(3\times 3\) convolution (\(C \to C\)), costing \(9HWC^2\) FLOPs.

- A \(1\times 1\) convolution to restore dimensionality (\(C \to 4C\)), costing another \(4HWC^2\) FLOPs.

This totals to \(17HWC^2\) FLOPs per block.

ResNeXt modifies this by introducing G parallel pathways, each containing an intermediate channel count \(c\): \begin {equation} \mbox{FLOPs per pathway} = (8Cc + 9c^2)HW \end {equation} Summing over \(G\) pathways results in: \begin {equation} \mbox{Total FLOPs} = (8Cc + 9c^2)HWG \end {equation}

To maintain the same computational cost, we solve: \begin {equation} 9Gc^2 + 8GCc - 17C^2 = 0 \end {equation} Example solutions:

- \(C=64, G=4, c=24\)

- \(C=64, G=32, c=4\)

Therefore, with ResNeXt blocks, we now have the freedom to play with values of \(C,G,c\), and as long as the values solve the equation: \(9Gc^2 + 8GCc - 17C^2 = 0\), enjoy from different architectures with the same computational cost (i.e., the same number of FLOPs).

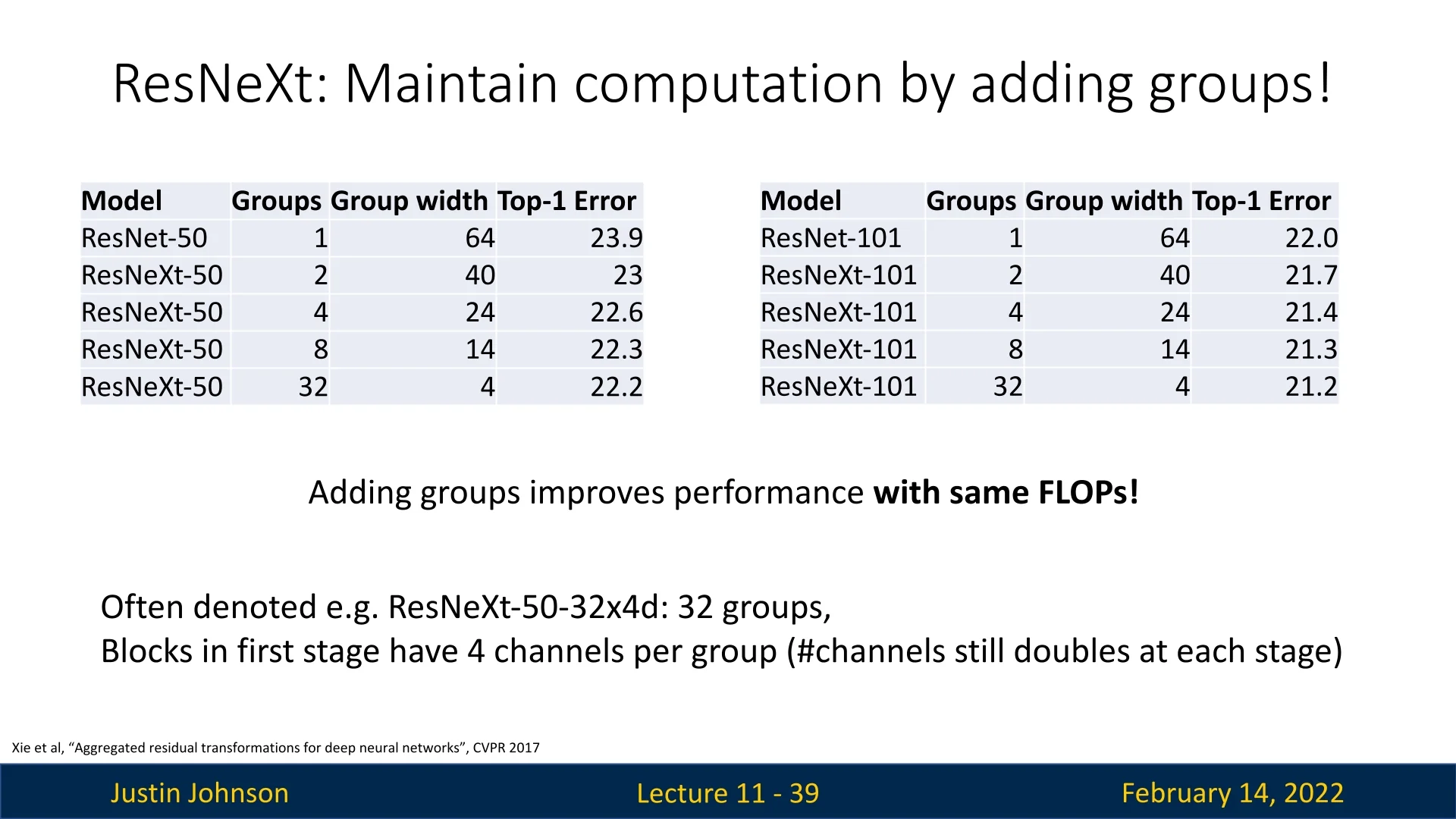

From testing it empirically, it appears that we can use this argument, and that by increasing the number of groups (\(G\)) while concurrently reducing the group width, we can improve performance while preserving the number of FLOPs.

11.3.3 ResNeXt and Grouped Convolutions

ResNeXt’s implementation can also be formulated in terms of grouped convolutions, making it easy to construct them in practice. Instead of explicitly creating multiple transformation pathways, we use grouped convolutions to enforce this structure efficiently.

Each ResNeXt block is structured as:

- \(1\times 1\) convolution (\(4C \to Gc\))

- \(3\times 3\) grouped convolution (\(Gc \to Gc\), groups=G)

- \(1\times 1\) convolution (\(Gc \to 4C\))

11.3.4 Advantages of ResNeXt Over ResNet

ResNeXt builds upon the ResNet design by introducing a structured, multi-pathway architecture that enhances representational power without incurring significant additional computational cost.

To summarize, ResNeXt’s key advantages over ResNet include:

- Improved Accuracy: The additional parallel transformation pathways enable richer feature extraction, leading to higher accuracy.

- Enhanced Efficiency: Instead of merely increasing network depth or width, ResNeXt uses grouped convolutions (parameterized by \(G\)) to boost capacity efficiently, outperforming deeper or wider ResNets at a similar computational cost.

11.3.5 ResNeXt Model Naming Convention

ResNeXt models are typically denoted as ResNeXt-50-32x4d, where:

- 50: Number of layers.

- 32: Number of groups (\(G\)).

- 4: Number of intermediate channels (dimensions) per group.

ResNeXt’s design principles went on to influence many later architectures, shaping how modern networks balance efficiency and expressiveness. Its core idea of aggregated transformations—splitting a feature map into parallel low-dimensional paths, transforming them independently, and then merging the results—proved broadly applicable beyond residual networks. This concept of scalable parallelism inspired the development of subsequent families of models that sought to improve performance not by simply increasing depth or width, but by refining how computations are organized. Later architectures such as EfficientNet and Vision Transformers (ViTs), which will be discussed in later chapters, extend this idea in different forms: one through highly efficient grouped and depthwise operations, and the other through parallel multi-head transformations. In both cases, the underlying philosophy introduced by ResNeXt—that richer representations can emerge from multiple lightweight, independent transformations rather than a single monolithic one—became a lasting design pattern across deep learning.

11.4 Squeeze-and-Excitation Networks (SENet)

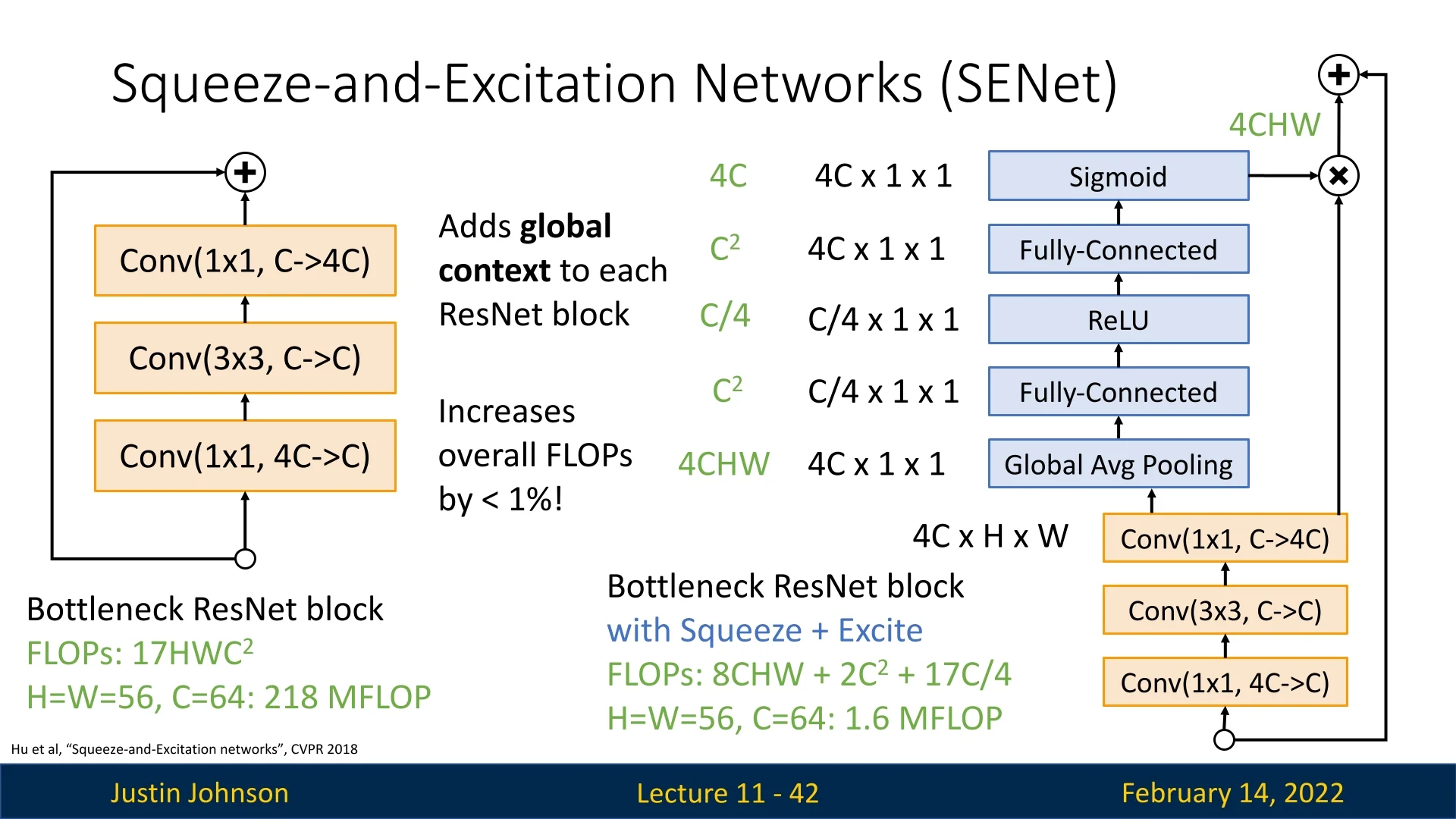

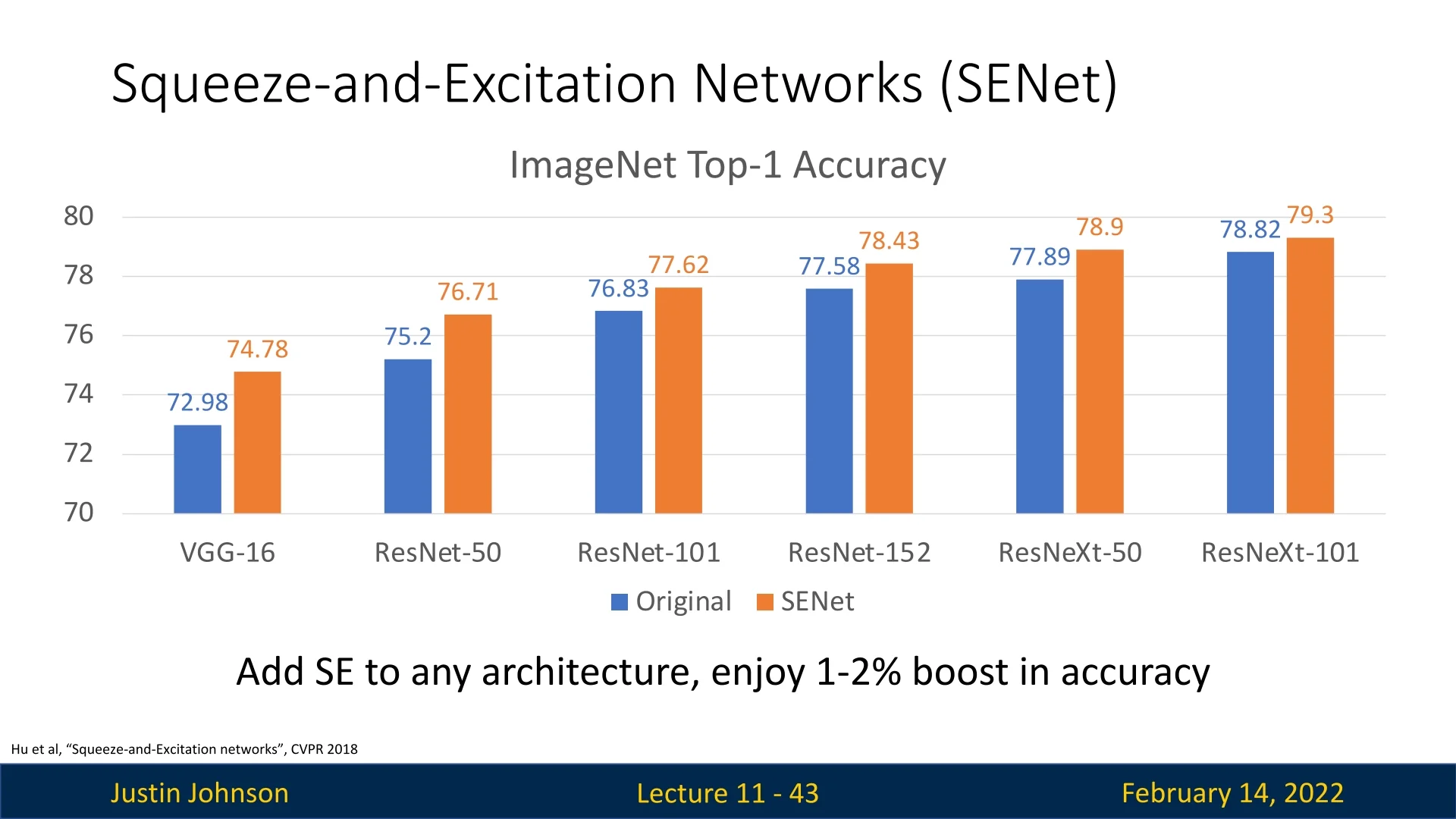

In 2017, researchers expanded upon ResNeXt by introducing Squeeze-and-Excitation Networks (SENet), which introduced a novel Squeeze-and-Excitation (SE) block [234]. The core idea behind SENet was to incorporate global channel-wise attention into ResNet blocks, improving the model’s ability to capture interdependencies between channels. This enhancement led to improved classification accuracy while adding minimal computational overhead.

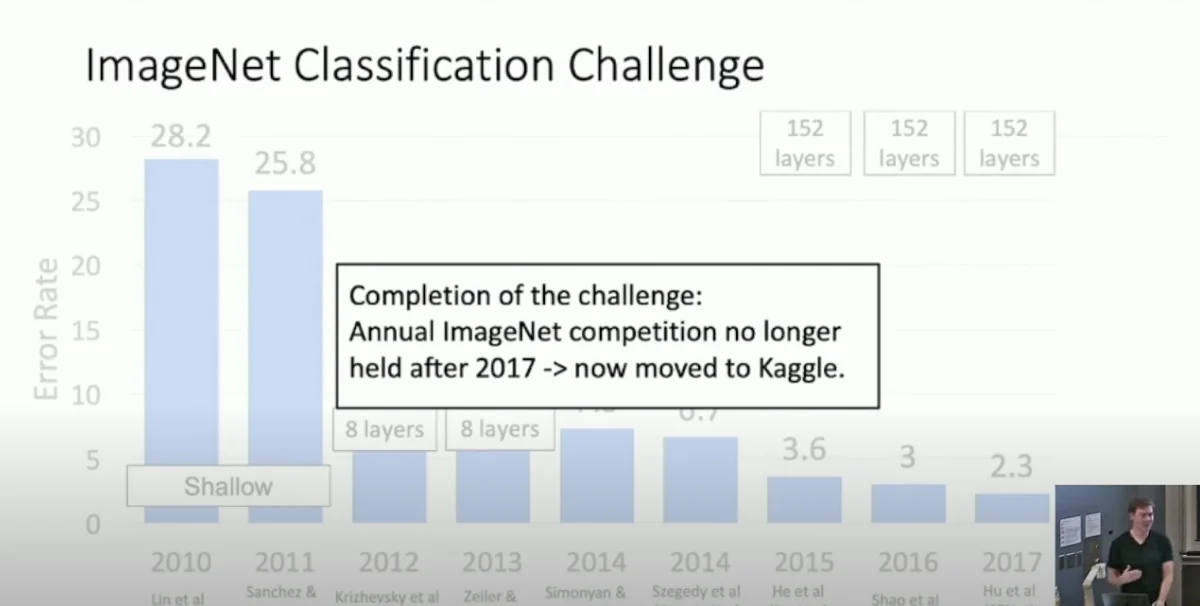

SENet won first place in the ILSVRC 2017 classification challenge, achieving a top-5 error rate of 2.251%, a remarkable 25% relative improvement over the winning model of 2016.

11.4.1 Squeeze-and-Excitation (SE) Block

The SE block is designed to enhance the representational power of convolutional networks by introducing a channel-wise attention mechanism. Instead of treating all channels equally, SE blocks allow the network to dynamically recalibrate the importance of different feature channels by learning their global interdependencies.

In standard convolutional layers, feature maps are processed independently across channels, meaning each filter learns to extract spatial patterns without directly considering how different feature channels relate to one another. The SE block addresses this limitation by introducing a two-step process: Squeeze and Excitation.

Squeeze: Global Information Embedding

Each convolutional layer in a ResNet bottleneck block produces a set of feature maps, where each channel captures different aspects of the input. However, these feature maps primarily focus on local spatial information, meaning that each activation in a feature map is computed independently of global image context.

To address this, the squeeze operation applies global average pooling across all spatial locations, condensing the entire spatial feature representation into a compact channel descriptor. This descriptor captures global context, summarizing the overall activation strength for each channel: \begin {equation} z_c = \frac {1}{H \times W} \sum _{i=1}^{H} \sum _{j=1}^{W} U_c(i,j) \end {equation} where:

- \(U_c(i,j)\) is the activation at spatial position \((i,j)\) for channel \(c\).

- \(z_c\) is a single scalar that represents the global response of channel \(c\).

This operation transforms each feature map from a spatial feature map of shape \((H, W)\) into a single scalar value, providing a compact summary of the channel’s overall importance.

Excitation: Adaptive Recalibration

While the squeeze operation extracts global statistics, it does not yet provide a mechanism for adjusting the importance of each channel. The excitation step models channel-wise dependencies by learning how much each channel should contribute to the final representation.

The excitation process consists of two fully connected (FC) layers, followed by a sigmoid activation: \begin {equation} s = \sigma (W_2 \delta (W_1 z)) \end {equation} where:

- \(W_1 \in \mathbb {R}^{C/r \times C}\) and \(W_2 \in \mathbb {R}^{C \times C/r}\) are learnable weight matrices.

- \(\delta \) is the ReLU activation function.

- \(\sigma \) is the sigmoid activation function, ensuring that each recalibration weight is in the range \((0,1)\).

- \(r\) is the reduction ratio, a hyperparameter controlling the dimensionality bottleneck.

Channel Recalibration

The output of the excitation function is a set of learned channel-wise scaling factors \(s = [s_1, s_2, ..., s_C]\), where each \(s_c\) determines how important the corresponding channel \(c\) is. These learned scalars are applied to the original feature maps using channel-wise multiplication: \begin {equation} \tilde {U}_c = s_c \cdot U_c \end {equation} where each feature map is rescaled according to its learned importance. Channels with high \(s_c\) values are emphasized, while those with low values are suppressed.

How SE Blocks Enhance ResNet Bottleneck Blocks

SE blocks are an additional component that can be inserted into any convolutional block. In ResNet’s bottleneck block, SE is added before the final summation with the shortcut connection. The process can be summarized as follows:

- 1.

- The input feature maps pass through the standard bottleneck

transformation:

- \(1 \times 1\) convolution reduces dimensions (\(4C \to C\)).

- \(3 \times 3\) convolution extracts spatial features (\(C \to C\)).

- \(1 \times 1\) convolution restores dimensions (\(C \to 4C\)).

- 2.

- Instead of immediately proceeding to the residual summation, the feature

maps are processed by an SE block:

- Global average pooling (squeeze) reduces each feature map to a scalar.

- Two fully connected layers (excitation) learn per-channel importance.

- The feature maps are reweighted based on their learned importance.

- 3.

- The recalibrated feature maps are passed to the identity shortcut connection and summed, completing the residual connection.

Why Does SE Improve Performance?

- Improved Feature Selection: SE blocks enable the network to focus on the most relevant channels, reducing noise and improving discrimination.

- Global Context Awareness: By incorporating global average pooling, the model learns to adjust features based on the entire input, rather than relying solely on local spatial filters.

-

Minimal Computational Overhead: Adding SE blocks increases FLOPs only marginally (usually by less than 1%). For example, in a ResNet bottleneck block:

- Without SE: \(17HWC^2\) FLOPs.

- With SE: \(8CHW + 2C^2 + \frac {17}{4}C\) FLOPs.

For \(H=W=56, C=64\), this translates to an increase from 218 MFLOPs to 219.6 MFLOPs.

Performance Gains, Scalability, and Integration of SE Blocks

Incorporating SE blocks consistently improves accuracy across various architectures. By introducing dynamic channel-wise attention, SE blocks enable CNNs to focus on the most relevant features, improving feature discrimination without significant computational overhead.

Impact on Various Tasks

SE blocks enhance performance across multiple domains:

- Image Classification: SE-ResNet-50 achieves a top-5 error of 6.62% compared to 7.48% for ResNet-50. Similar improvements occur in SE-ResNet-101, SE-ResNeXt-50, and SE-Inception-ResNet-v2.

- Object Detection: Integrating SE into Faster R-CNN with a ResNet-50 backbone improves average precision by 1.3% on COCO, a relative gain of 5.2%.

- Scene Classification: SE-ResNet-152 reduces the Places365 top-5 error from 11.61% to 11.01%.

Practical Applications and Widespread Adoption

Due to their efficiency and adaptability, SE blocks have been widely integrated into many advanced architectures beyond classification:

- Object Detection: Faster R-CNN and RetinaNet benefit from SE-enhanced backbone networks.

- Semantic Segmentation: DeepLab and U-Net architectures integrate SE blocks to improve feature selection.

- Lightweight Models: MobileNet and ShuffleNet variants incorporate SE blocks, enhancing feature discrimination without significantly increasing computation.

SE blocks thus serve as a general-purpose enhancement that improves accuracy across diverse architectures and applications with minimal computational trade-offs.

11.4.2 SE Blocks and the End of the ImageNet Classification Challenge

The introduction of SE blocks in 2017 marked a turning point in the history of deep learning for image classification. With the Squeeze-and-Excitation Network (SENet) winning the ILSVRC 2017 classification challenge by a significant margin, the ImageNet competition had effectively reached its saturation point. The classification problem that had driven progress in convolutional neural networks (CNNs) for years was, metaphorically, squeezed to a pulp.

With SENet achieving a top-5 error rate of 2.251%, nearly matching human-level performance on ImageNet, it became clear that further improvements in classification accuracy would yield diminishing returns. The focus of research started shifting away from pure classification improvements and toward efficiency, enabling CNNs to be deployed on real-world devices.

11.4.3 Challenges and Solutions for SE Networks

Challenges of SE Networks

While Squeeze-and-Excitation (SE) blocks offer performance improvements, they introduce certain limitations that can impact their effectiveness in deep learning architectures:

- Loss of Spatial Information: Since SE blocks operate exclusively on channel-wise statistics, they ignore spatial relationships between pixels. This is particularly problematic for tasks requiring fine-grained spatial awareness, such as semantic segmentation or object detection.

- Increased Computational Cost: The excitation step involves two fully connected layers, introducing additional parameters and increasing inference time, which can be a concern in real-time applications or mobile deployments.

- Feature Over-suppression: If the learned channel-wise attention weights are improperly calibrated, they may suppress essential features, degrading model performance by eliminating useful information.

Solutions to SE Network Challenges

To address these challenges, several modifications and enhancements have been proposed:

- Combining SE with Spatial Attention: To mitigate the loss of spatial information, SE blocks can be integrated with spatial attention mechanisms, such as CBAM (Convolutional Block Attention Module) [697], which applies both channel-wise and spatial attention to improve feature selection. We will explore attention mechanisms in more detail in a later part of the course.

- Lightweight Excitation Mechanisms: The computational cost of SE blocks can be reduced by using depthwise separable convolutions instead of fully connected layers, as demonstrated in MobileNetV3 [230]. This allows for efficient feature recalibration without a significant increase in parameters.

- Normalization-Based Calibration: Applying normalization techniques, such as BatchNorm or GroupNorm, in the excitation step can help stabilize activations and prevent over-suppression of important features, leading to more balanced feature scaling.

Despite these challenges, SE blocks remain a widely used technique for enhancing neural network performance, particularly in mobile architectures where efficiency and accuracy need to be balanced carefully.

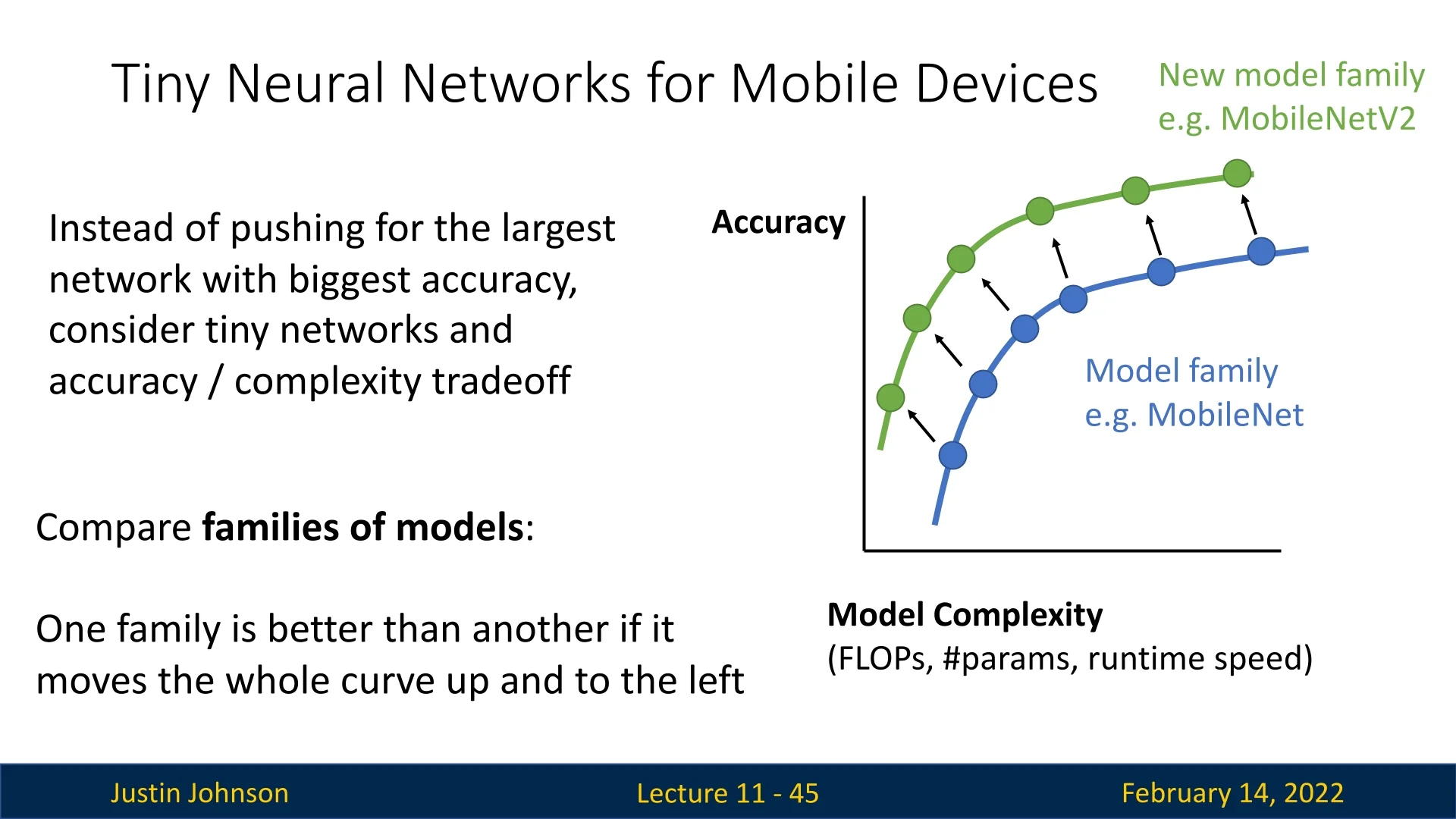

Shifting Research Directions: Efficiency and Mobile Deployability

While deeper and more powerful models like SENet were being developed, practical applications demanded lightweight and efficient networks that could run on resource-constrained devices such as mobile phones, embedded systems, and edge devices. This need led to a new era of model design, emphasizing:

- Reducing computational complexity while maintaining accuracy.

- Optimizing models for mobile and embedded hardware (e.g., efficient CNN architectures).

- Exploring new paradigms beyond conventional CNN-based feature extraction.

What Comes Next?

In the following sections, we will explore some of the architectures that emerged as a response to these practical challenges:

- MobileNets: Depthwise separable convolutions for efficient mobile-friendly models.

- ShuffleNet: Grouped convolutions with channel shuffling to optimize computation.

- EfficientNet: Compound scaling of depth, width, and resolution to maximize accuracy per FLOP.

These models set the stage for efficient deep learning, shifting the paradigm from brute-force accuracy improvements to optimal model design for real-world deployment.

11.5 Efficient Architectures for Edge Devices

As deep learning models become increasingly powerful, their computational demands also rise sharply. Yet many real-world applications—such are running on smartphones or other embedded systems like in autonomous vehicles. In this section, we explore the evolution of CNN architectures designed for embedded systems, aiming to optimize the accuracy-to-FLOP ratio, striking a careful balance between computational efficiency and predictive performance.

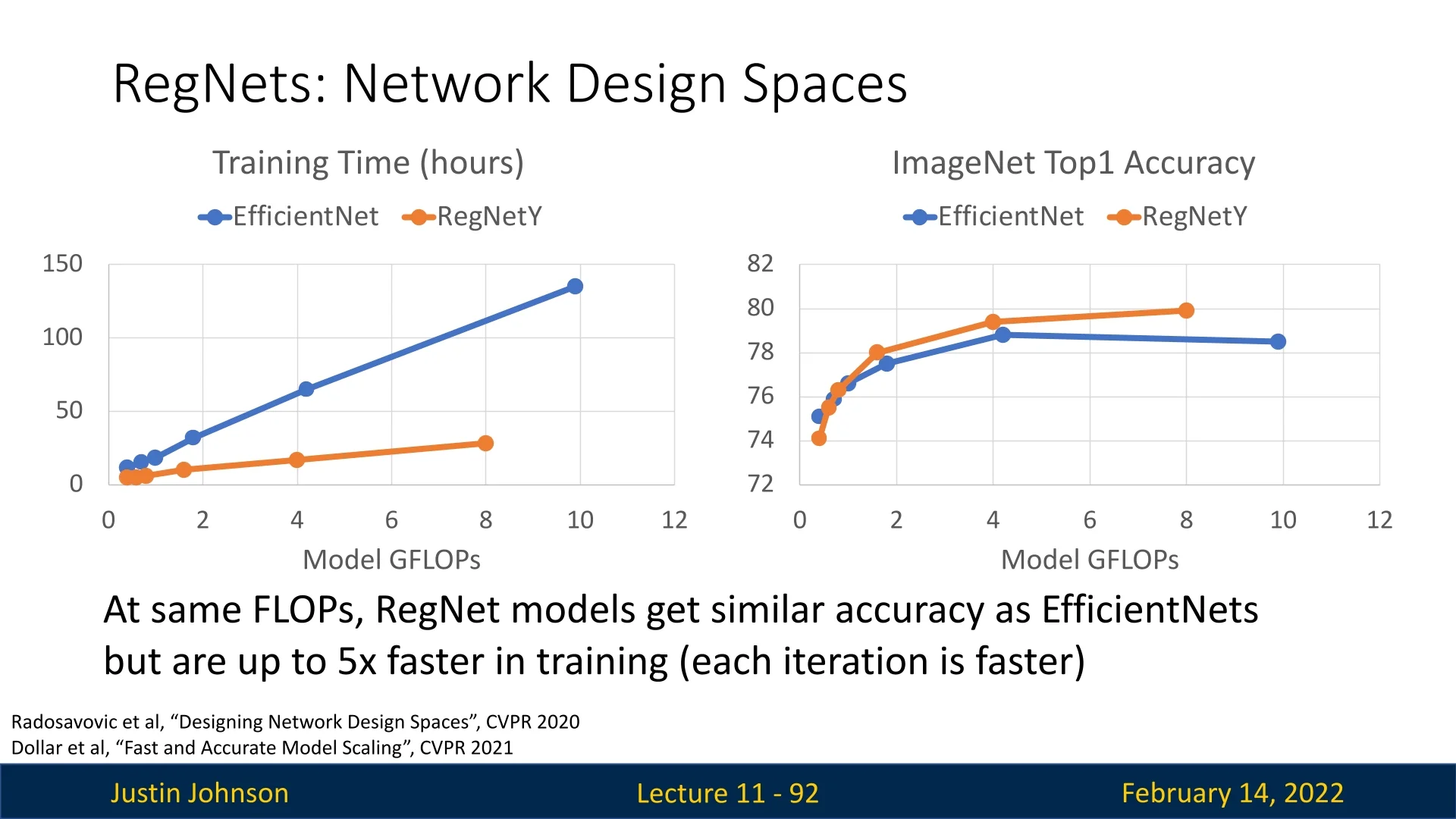

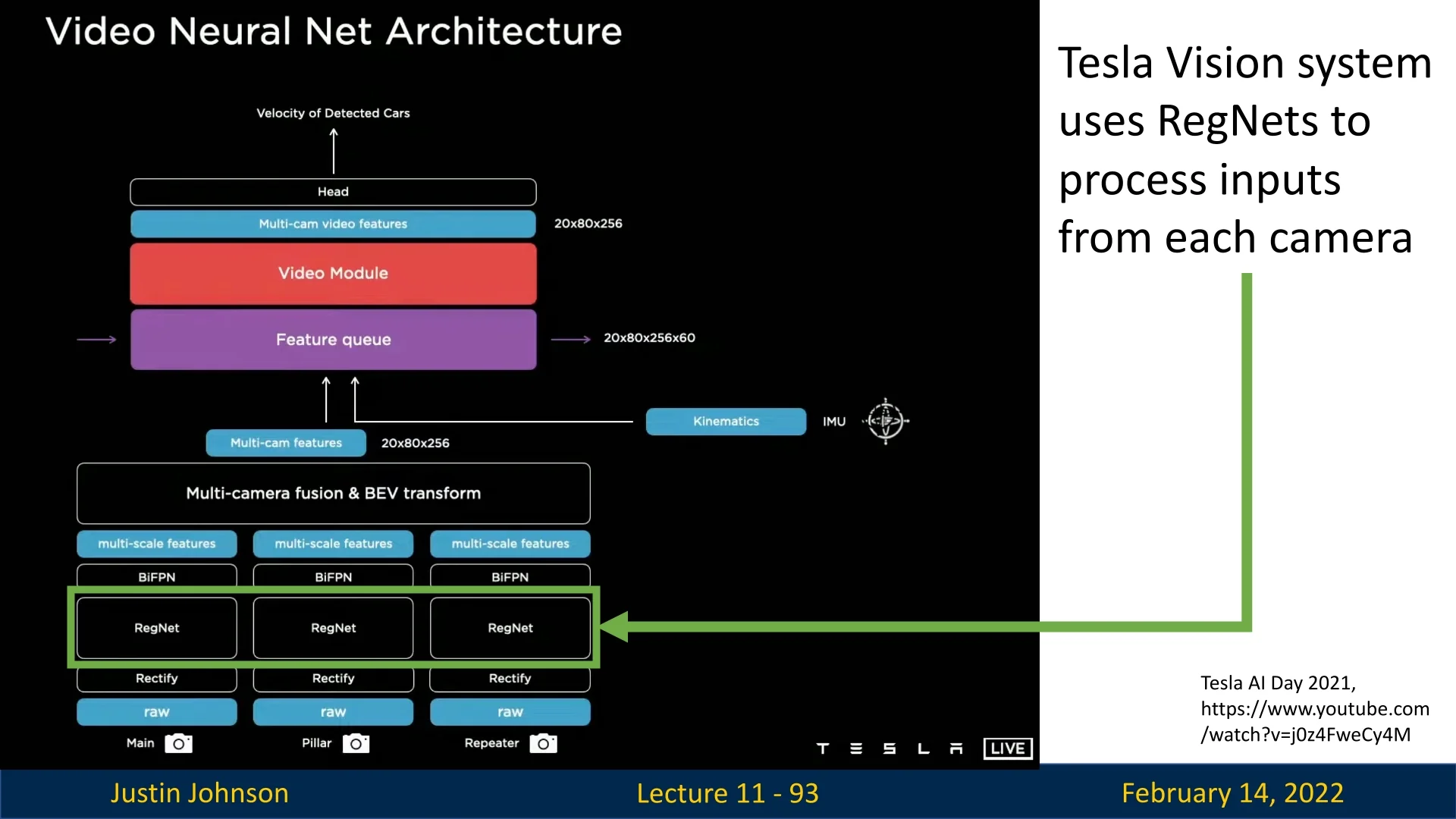

The journey in efficient deep learning begins with MobileNets, which introduced depthwise separable convolutions to dramatically reduce computational cost while preserving competitive accuracy. Subsequent innovations, such as ShuffleNet, further improved efficiency by reorganizing channel connectivity. More recently, advanced models like EfficientNet have pushed the boundaries by jointly scaling network depth, width, and resolution. Competing architectures such as RegNet offer similar accuracy at the same FLOP level while achieving up to five times faster training speeds.

In the following subsections, we trace the development of these efficient architectures—from the early MobileNets and ShuffleNet to the latest EfficientNet and RegNet models—highlighting the key design principles and innovations that make them well-suited for deployment on edge devices.

11.5.1 MobileNet: Depthwise Separable Convolutions

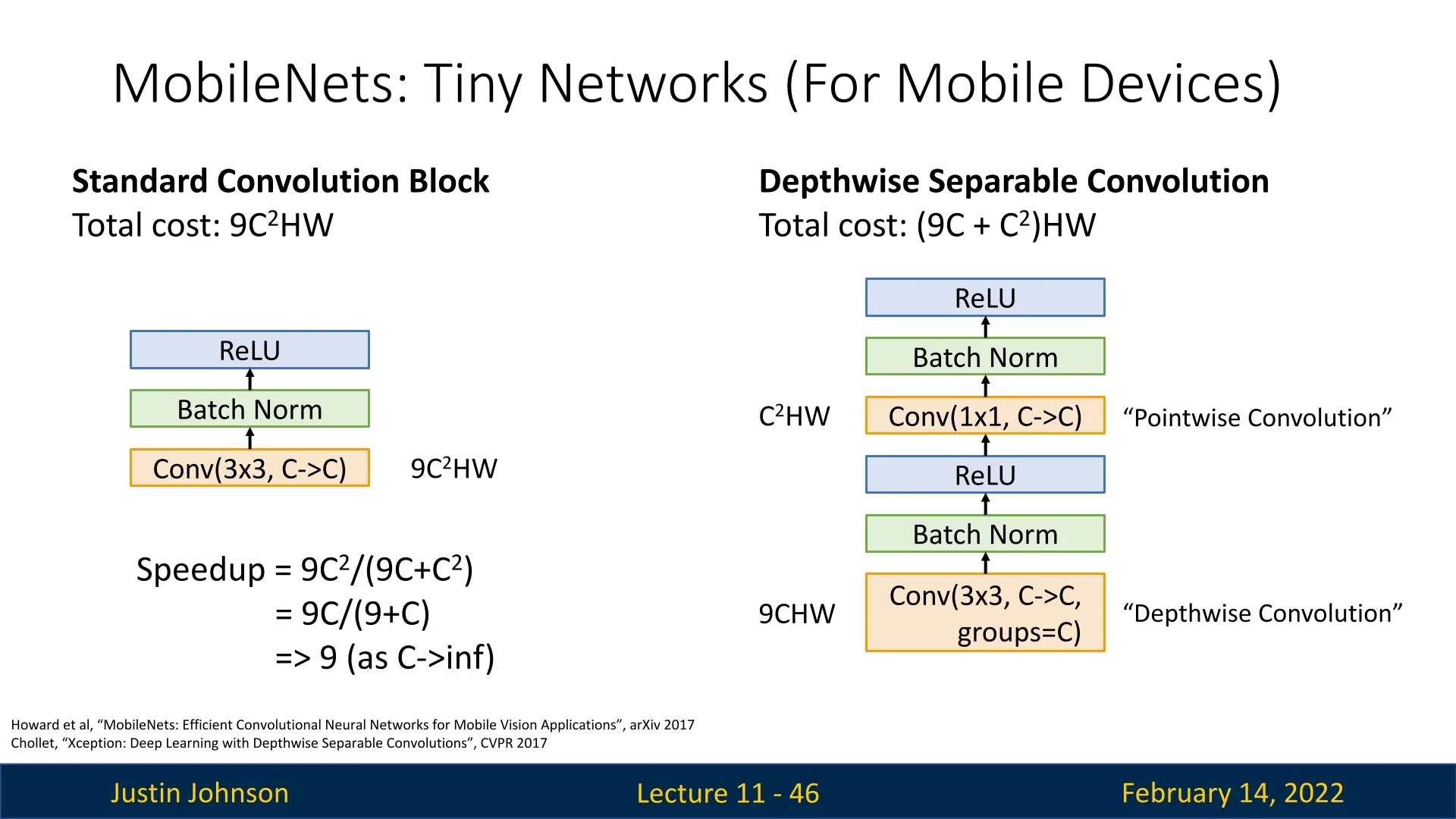

MobileNetV1 was designed to create highly efficient neural networks that could run in real-time on low-power devices. The key innovation behind MobileNet is its use of Depthwise Separable Convolutions, which factorize a standard convolution operation into two separate steps:

- 1.

- A Depthwise Convolution, where a single convolutional filter is applied per input channel (instead of applying filters across all channels as in standard convolutions).

- 2.

- A Pointwise Convolution (\(1 \times 1\) convolution), which projects the depthwise output back into a full feature representation.

This decomposition significantly reduces the number of computations required while still maintaining sufficient expressiveness.

To understand the efficiency gain, consider the computational cost:

- Standard Convolution: \(9C^2HW\) FLOPs.

- Depthwise Separable Convolution: \((9C + C^2)HW\) FLOPs.

The speedup is given by: \begin {equation} \frac {9C^2}{9C + C^2} = \frac {9C}{9+C} \end {equation} As \(C \to \infty \), the speedup approaches 9\(\times \), demonstrating the substantial computational savings.

Width Multiplier: Thinner Models

A key parameter in MobileNet is the width multiplier \(\alpha \in (0,1]\). It uniformly scales the number of channels in each layer: \[ \mbox{(Input channels)} \;\mapsto \; \alpha \times (\mbox{Input channels}), \quad \mbox{(Output channels)} \;\mapsto \; \alpha \times (\mbox{Output channels}). \] When \(\alpha =1\), MobileNet uses the baseline channel sizes. As \(\alpha \) decreases, the network becomes thinner at every layer, reducing both computation and parameters approximately by \(\alpha ^2\). Typical choices include \(\alpha \in \{1, 0.75, 0.5, 0.25\}\), which trade off accuracy for efficiency in a predictable manner.

Resolution Multiplier: Reduced Representations

Another hyperparameter to control model size is the resolution multiplier \(\rho \in (0,1]\). It uniformly scales the spatial resolution at each layer: \[ \mbox{(Input height/width)} \;\mapsto \; \rho \times (\mbox{Input height/width}), \] and similarly for intermediate feature-map resolutions. Reducing resolution can shrink the FLOPs by approximately \(\rho ^2\). Common input resolutions are \(\{224,192,160,128\}\), corresponding to \(\rho = 1,\,0.86,\,0.71,\,0.57\) relative to \(224\times 224\).

Computational Cost of Depthwise Separable Convolutions

In MobileNet, each layer is a depthwise separable convolution, split into:

- 1.

- Depthwise Conv \((K \times K)\): One spatial filter per input channel.

- 2.

- Pointwise Conv \((1 \times 1)\): A standard convolution across all input channels to produce output channels.

If the baseline layer has \(\,M\) input channels, \(\,N\) output channels, kernel size \(K\!\times K\), and spatial dimension \(D\!\times D\), then the total FLOPs for a depthwise separable layer are: \[ \underbrace {(K \times K) \cdot M \cdot D^2}_{\mbox{Depthwise}} \;+\; \underbrace {(1 \times 1)\cdot M \cdot N \cdot D^2}_{\mbox{Pointwise}}. \] Applying the width multiplier \(\alpha \) and resolution multiplier \(\rho \) modifies the above to: \[ (K \times K)\,\cdot \,(\alpha M)\,\cdot \,(\rho D)^2 \;+\; (\alpha M)\,\cdot \,(\alpha N)\,\cdot \,(\rho D)^2, \] which can be written as: \[ (\rho D)^2 \bigl [ (K^2)\,\alpha M \;+\; \alpha ^2 (M \cdot N) \bigr ]. \] Hence, choosing smaller \(\alpha \) or \(\rho \) scales down the network’s computation and number of parameters, at the cost of some accuracy.

Summary of Multipliers Together, the width and resolution multipliers \((\alpha , \rho )\) provide a simple yet powerful mechanism to tailor MobileNet to a wide range of resource constraints, making it suitable for both high-performance and highly constrained edge-device environments.

MobileNetV1 vs. Traditional Architectures

Despite its lightweight design, MobileNetV1 achieves remarkable efficiency compared to traditional CNNs. Table 11.1 highlights a comparison on the ImageNet dataset.

MobileNet-224 achieves nearly the same accuracy as VGG-16 while using 97% fewer parameters and 96% fewer FLOPs, making it an ideal choice for real-time edge applications.

Depthwise Separable vs. Standard Convolutions in MobileNet

To understand the tradeoffs involved in using depthwise separable convolutions, the following table compares a regular convolutional MobileNet to one using depthwise separable convolutions.

The use of depthwise separable convolutions results in:

- A slight drop in accuracy (71.7% \(\to \) 70.6%).

- A 7\(\times \) reduction in parameters (29.3M \(\to \) 4.2M).

- A 9\(\times \) reduction in FLOPs (4866M \(\to \) 569M).

This tradeoff is highly favorable for edge applications where computational efficiency is critical.

Summary and Next Steps

MobileNetV1 demonstrated that Depthwise Separable Convolutions can drastically reduce computational cost while maintaining competitive accuracy. By factorizing a standard convolution into a 3×3 depthwise convolution (mixing spatial information) followed by a 1×1 pointwise convolution (mixing channel information), the model achieves significant efficiency gains.

However, a key limitation remains: the 1×1 pointwise convolution still operates on all channels uniformly. Since this convolution processes each channel independently before recombining them, there is room for optimization in how channels interact.

What’s the problem? The current design lacks an explicit mechanism to exchange information across different channels efficiently. Consider an alternative approach: grouped convolutions, which split channels into independent groups to reduce computational cost. While grouped convolutions lower the FLOP count, they introduce a new issue—channels within a group never interact with channels from other groups. This results in each output channel only depending on a limited subset of input channels, restricting the model’s capacity to learn rich feature representations.

This observation raises a fundamental question: Can we mix channel information more efficiently while maintaining the computational benefits of grouped convolutions?

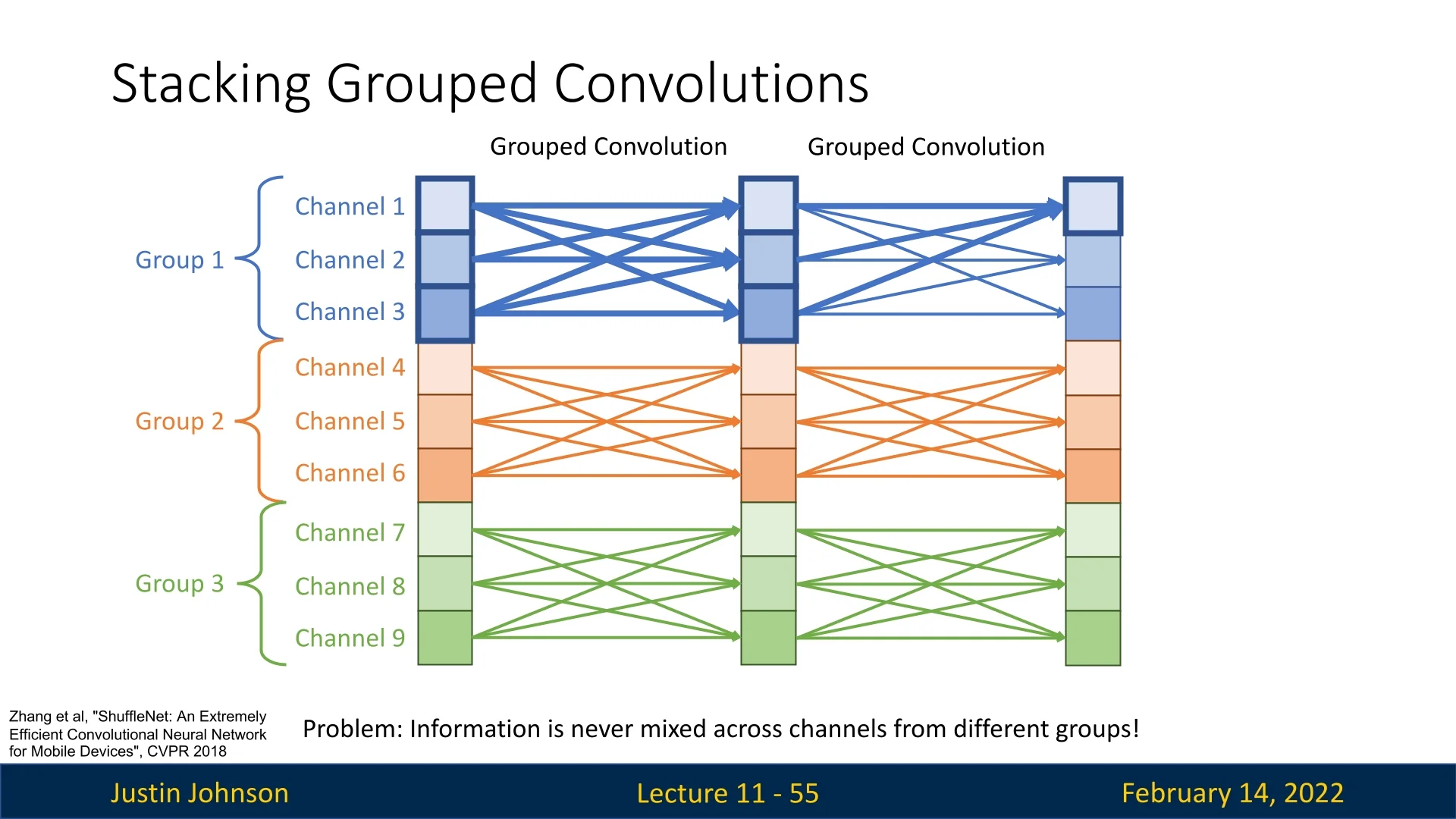

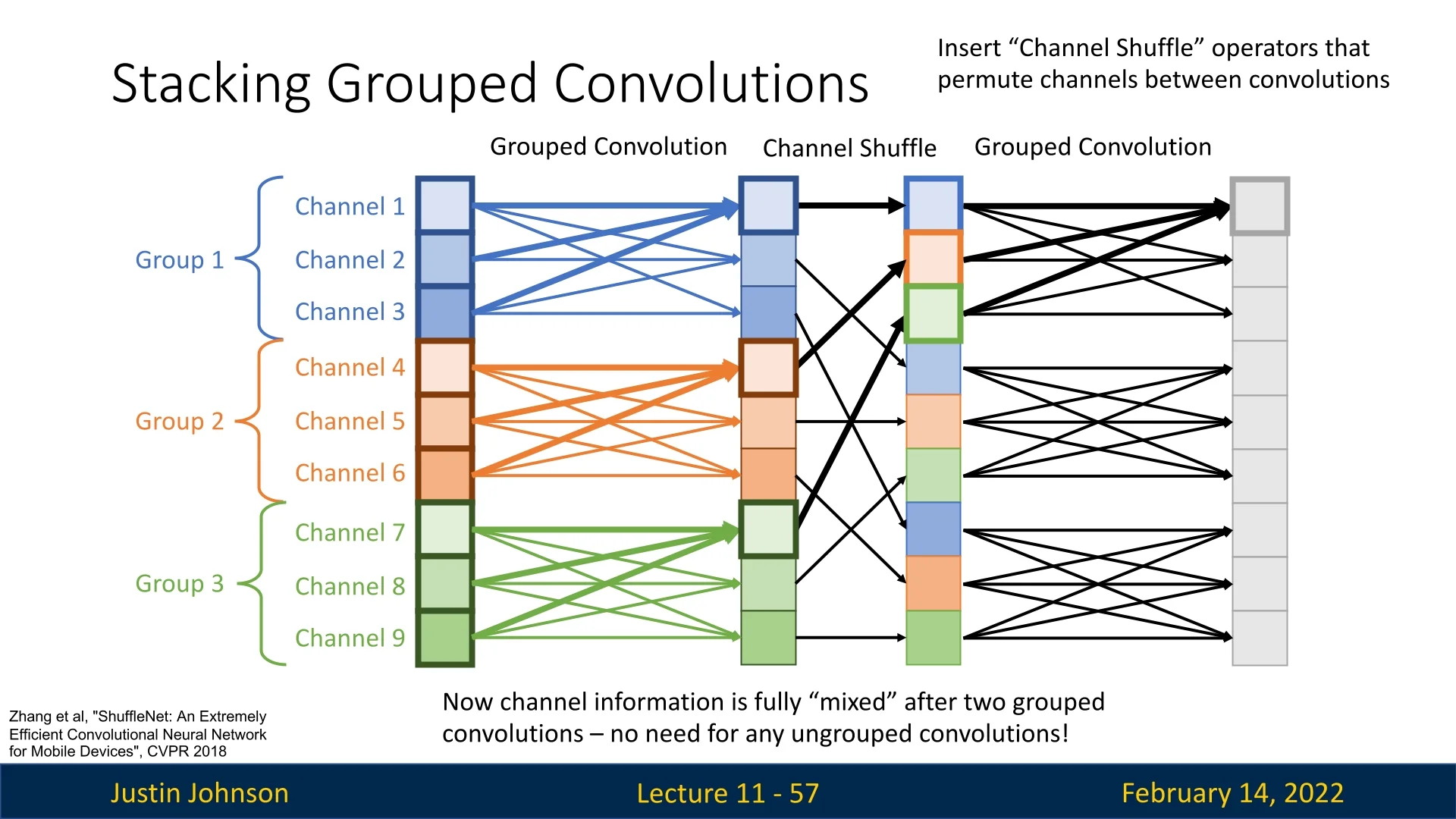

11.5.2 ShuffleNet: Efficient Channel Mixing via Grouped Convolutions

MobileNetV1 demonstrated that depthwise separable convolutions can significantly reduce computational cost. However, this design shifts most of the computation into the \(1\times 1\) pointwise convolutions, which are responsible for mixing information across channels. A natural way to further reduce cost is to use grouped convolutions in these layers, but this introduces a new limitation: channels become isolated within their groups, so information cannot easily flow from one group to another.

Solution: ShuffleNet [780]. ShuffleNet introduces the channel shuffle operation, which explicitly re-mixes channels across groups between successive grouped convolutions. The pattern is: \[ \mbox{grouped conv} \;\rightarrow \; \mbox{channel shuffle} \;\rightarrow \; \mbox{grouped conv}. \] After shuffling, each output group in the next layer receives channels originating from multiple input groups, restoring cross-group interaction while preserving the efficiency gains of grouped convolutions.

How the Channel Shuffle Works Consider a feature map \(X \in \mathbb {R}^{N \times C \times H \times W}\) (batch size \(N\), channels \(C\), height \(H\), width \(W\)) processed by a grouped convolution with \(g\) groups. The channels are conceptually partitioned into \(g\) groups of size \(C_g = C/g\) each. The channel shuffle is a fixed permutation of the channel dimension, implemented in three simple tensor operations:

- 1.

- Reshape: View the channel dimension as \((g, C_g)\): \[ X \in \mathbb {R}^{N \times C \times H \times W} \;\longrightarrow \; X' \in \mathbb {R}^{N \times g \times C_g \times H \times W}. \] Each of the \(g\) entries in the second dimension corresponds to one group.

- 2.

- Transpose (swap groups and within-group channels): \[ X' \in \mathbb {R}^{N \times g \times C_g \times H \times W} \;\longrightarrow \; X'' \in \mathbb {R}^{N \times C_g \times g \times H \times W}. \] This interleaves the channels so that positions that were previously in the same group are now spread across different groups.

- 3.

- Reshape back: \[ X'' \in \mathbb {R}^{N \times C_g \times g \times H \times W} \;\longrightarrow \; \tilde {X} \in \mathbb {R}^{N \times C \times H \times W}, \] where the channels of \(\tilde {X}\) are now a shuffled version of the original \(X\).

Intuitively, if you imagine dealing channels into \(g\) piles (groups), the shuffle operation re-deals them so that each new pile contains cards (channels) drawn from all the previous piles. When the next grouped convolution splits channels into \(g\) groups again, each group now contains information coming from all previous groups.

Differentiability of Channel Shuffle The channel shuffle is a purely indexing operation: it reorders channels but does not change their values. Mathematically, it corresponds to multiplying by a fixed permutation matrix along the channel dimension. Such a permutation is:

- Linear and invertible: no information is lost.

- Orthogonal: the inverse permutation simply reorders channels back.

During backpropagation, the gradient with respect to the input is obtained by applying the inverse permutation to the gradient with respect to the output. In practice, frameworks implement this as the same sequence of reshape/transpose operations in reverse order. Hence, the channel shuffle is fully differentiable and adds negligible computational overhead (no extra parameters, no multiplications), making it perfectly suitable for end-to-end training.

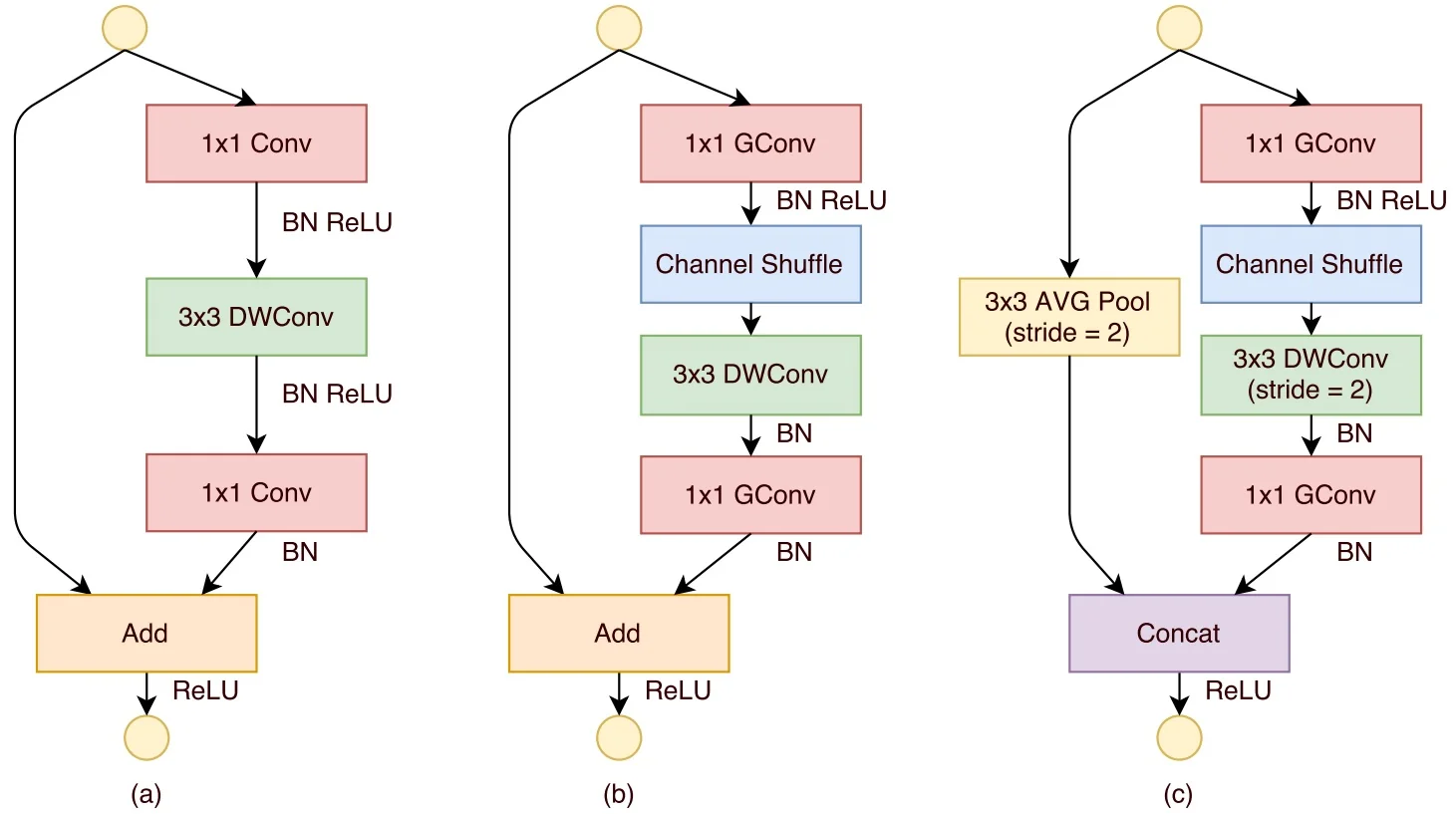

The ShuffleNet Unit

Motivation. In many lightweight CNNs (e.g., MobileNetV1), depthwise separable convolutions reduce the cost of spatial filtering, but the \(1\times 1\) pointwise convolutions remain expensive because they operate on all channels. ShuffleNet reduces this cost by:

- Applying grouped \(1\times 1\) convolutions to lower the FLOPs.

- Inserting a channel shuffle operation to avoid the isolation of channel groups.

- Grouped \(1\times 1\) Convolution: In contrast to ResNeXt (which typically groups only \(3\times 3\) convolutions), ShuffleNet also applies grouping to the \(1\times 1\) layers. Since pointwise convolutions often dominate the computation, grouping here yields substantial savings.

- Channel Shuffle Operation: Grouped convolutions alone process disjoint subsets of channels. By placing a channel shuffle between two grouped convolutions, ShuffleNet ensures that each group in the second convolution receives channels originating from multiple groups of the first, restoring effective cross-channel mixing.

Structure of a ShuffleNet Unit A standard ShuffleNet unit with stride \(1\) (Figure 11.22b) consists of:

- 1.

- A \(1\times 1\) grouped convolution (pointwise GConv), followed by batch normalization and a nonlinearity (e.g., ReLU).

- 2.

- A channel shuffle operation to re-mix channel groups.

- 3.

- A \(3\times 3\) depthwise convolution (DWConv) with stride 1, capturing spatial information at low cost, followed by batch normalization.

- 4.

- A second \(1\times 1\) grouped convolution to restore the channel dimension, followed by batch normalization.

- 5.

- A residual connection that adds the block input to the transformed output.

- 6.

- A final ReLU applied after the residual addition.

Stride-2 Modification When downsampling with stride \(2\) (Figure 11.22c), two modifications are introduced:

- The main branch uses a \(3\times 3\) depthwise convolution with stride \(2\) to reduce spatial resolution.

- The shortcut branch applies a \(3\times 3\) average pooling with stride \(2\) to match the main branch’s spatial dimensions.

- Instead of element-wise addition, the outputs of the main and shortcut branches are concatenated along the channel dimension. This preserves all features from both branches and increases the total number of channels, enhancing representational capacity.

ShuffleNet Architecture

The full ShuffleNet architecture is built by stacking ShuffleNet units into stages, similar to ResNet. Each stage operates at a fixed spatial resolution; the first unit in a stage downsamples and increases channels, while subsequent units keep the resolution constant.

- The first ShuffleNet unit in each stage performs downsampling with stride \(2\), reducing \(H\) and \(W\) while increasing the number of channels.

- Subsequent ShuffleNet units in the same stage use stride \(1\) to preserve spatial dimensions.

- At the beginning of each new stage, the number of output channels is doubled to compensate for reduced spatial resolution and maintain expressiveness.

- Within a ShuffleNet unit, the number of bottleneck channels is typically set to \(\frac {1}{4}\) of the block’s output channels, mirroring the bottleneck design in ResNet.

Scaling Factor Like other efficient models, ShuffleNet uses a width multiplier \(s\) to scale channel counts: \[ \mbox{ShuffleNet }s\times : \quad \#\mbox{Channels} = s \times \#\mbox{Channels in ShuffleNet }1\times . \] Increasing \(s\) increases model capacity and FLOPs (roughly by \(s^2\)), allowing practitioners to trade accuracy for compute depending on hardware constraints.

- Grouped \(1\times 1\) Convolutions reduce the cost of the most expensive layers.

- Channel Shuffle restores cross-group communication that would otherwise be lost with grouping.

- Stage-wise scaling (doubling channels when halving spatial size) balances efficiency and representational power across depth.

Overall, ShuffleNet provides an efficient alternative to MobileNet-type designs, showing how careful use of grouping and channel shuffling can reduce computation while preserving rich inter-channel mixing.

Computational Efficiency of ShuffleNet

To quantify ShuffleNet’s efficiency, consider a bottleneck block operating on an input feature map of spatial size \(H \times W\), with \(C\) input channels and \(m\) bottleneck channels. Let \(g\) denote the number of groups.

The approximate FLOPs for different bottleneck designs are:

- ResNet bottleneck block: \(H W \big (2 C m + 9 m^2\big )\) FLOPs.

- ResNeXt block: \(H W \big (2 C m + 9 m^2 / g\big )\) FLOPs (grouped \(3\times 3\) convolution).

- ShuffleNet block: \(H W \big (2 C m / g + 9 m\big )\) FLOPs (grouped \(1\times 1\), depthwise \(3\times 3\)).

Compared to ResNet and ResNeXt, ShuffleNet:

- reduces the cost of both \(1\times 1\) convolutions by a factor of \(g\), and

- replaces the dense \(3\times 3\) convolution (\(\mathcal {O}(m^2)\)) with a depthwise one (\(\mathcal {O}(m)\)).

This yields a substantial reduction in theoretical compute while maintaining good representational power via channel shuffle.

Inference Speed and Practical Performance

Theoretical FLOPs are only a proxy for real-world efficiency; memory access patterns and hardware characteristics matter as well. On ARM-based mobile processors, the ShuffleNet paper reports:

- A 4\(\times \) reduction in theoretical FLOPs compared to certain baselines translates into roughly a 2.6\(\times \) speedup in measured inference time.

- A group count of \(g = 3\) offers the best trade-off between accuracy and speed. Larger \(g\) (e.g., \(4\) or \(8\)) can slightly improve accuracy, but the extra overhead of more fragmented memory access and shuffling tends to hurt latency.

- The ShuffleNet \(0.5\times \) model achieves about a 13\(\times \) speedup over AlexNet in practice while maintaining comparable accuracy, despite a theoretical speedup of around \(18\times \).

These results highlight two key lessons:

- Channel shuffling makes grouped convolutions practically usable by restoring cross-channel mixing.

- Efficient architectures must be evaluated with both FLOPs and actual hardware performance in mind, especially for edge and mobile deployments.

Performance Comparison: ShuffleNet vs. MobileNet

To appreciate the practical impact of channel shuffling and grouped \(1\times 1\) convolutions, it is useful to compare ShuffleNet directly with MobileNetV1 at a similar computational budget on ImageNet.

| Model | Top-1 Accuracy (%) | Multi-Adds (M) | Parameters (M) |

|---|---|---|---|

| MobileNetV1 1.0\(\times \) (224) | 70.6 | 569 | 4.2 |

| ShuffleNet 1.0\(\times \) (g=3) | 71.7 | 524 | 5.0 |

In this regime, ShuffleNet gains accuracy per FLOP by (i) replacing dense \(1\times 1\) convolutions with grouped ones and (ii) restoring cross-channel interaction via channel shuffle. MobileNetV1 relies on depthwise separable convolutions but still uses dense \(1\times 1\) mixing; ShuffleNet shows that, with a carefully designed permutation (the shuffle), even the pointwise layers can be aggressively factorized without sacrificing, and in fact slightly improving, accuracy.

Beyond ShuffleNet: Evolution of Efficient CNN Architectures

ShuffleNet is part of a broader line of work on efficient CNNs for mobile and embedded devices. Its core ideas—cheap spatial filtering (depthwise conv), structured sparsity (grouped \(1\times 1\) conv), and explicit channel mixing (shuffle)—influenced how later architectures think about trading off compute, memory, and accuracy.

Subsequent models extend these principles in different directions:

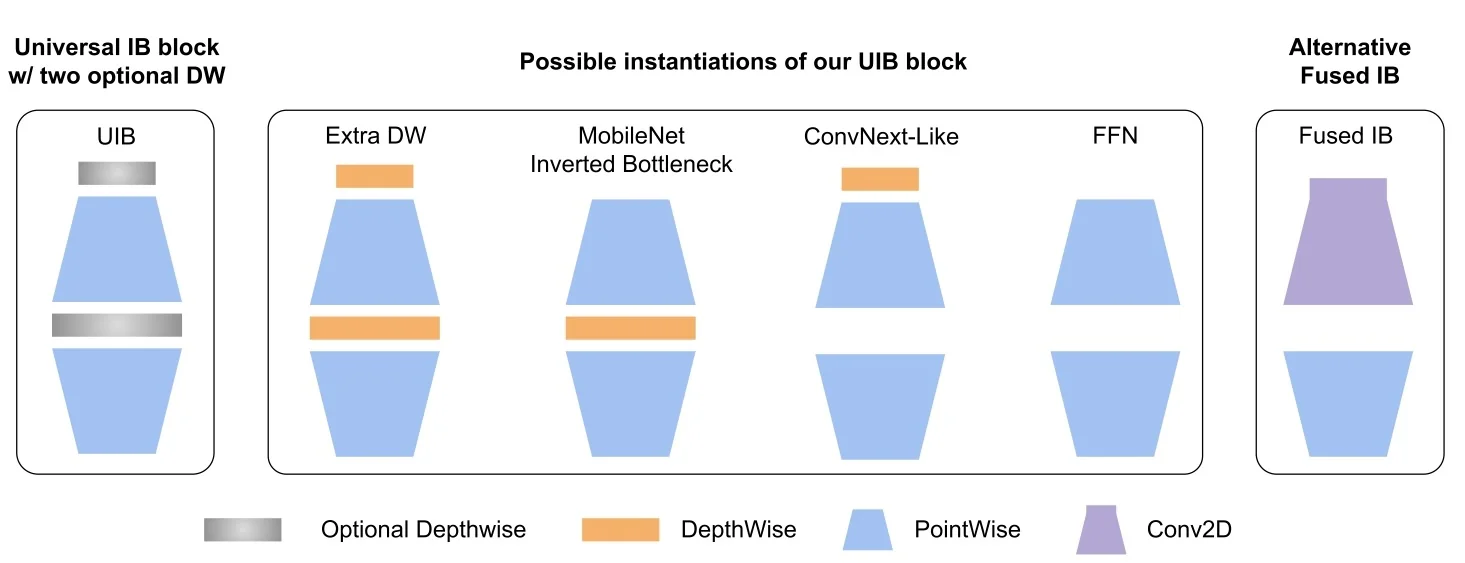

- MobileNetV2 introduces inverted residuals with linear bottlenecks, using depthwise convolutions inside narrow–wide–narrow blocks to reduce computation while preserving information in low-dimensional spaces.

- MobileNetV3 combines MobileNetV2-style blocks with neural architecture search (NAS) and lightweight attention (SE blocks), explicitly optimizing for mobile hardware latency rather than FLOPs alone.

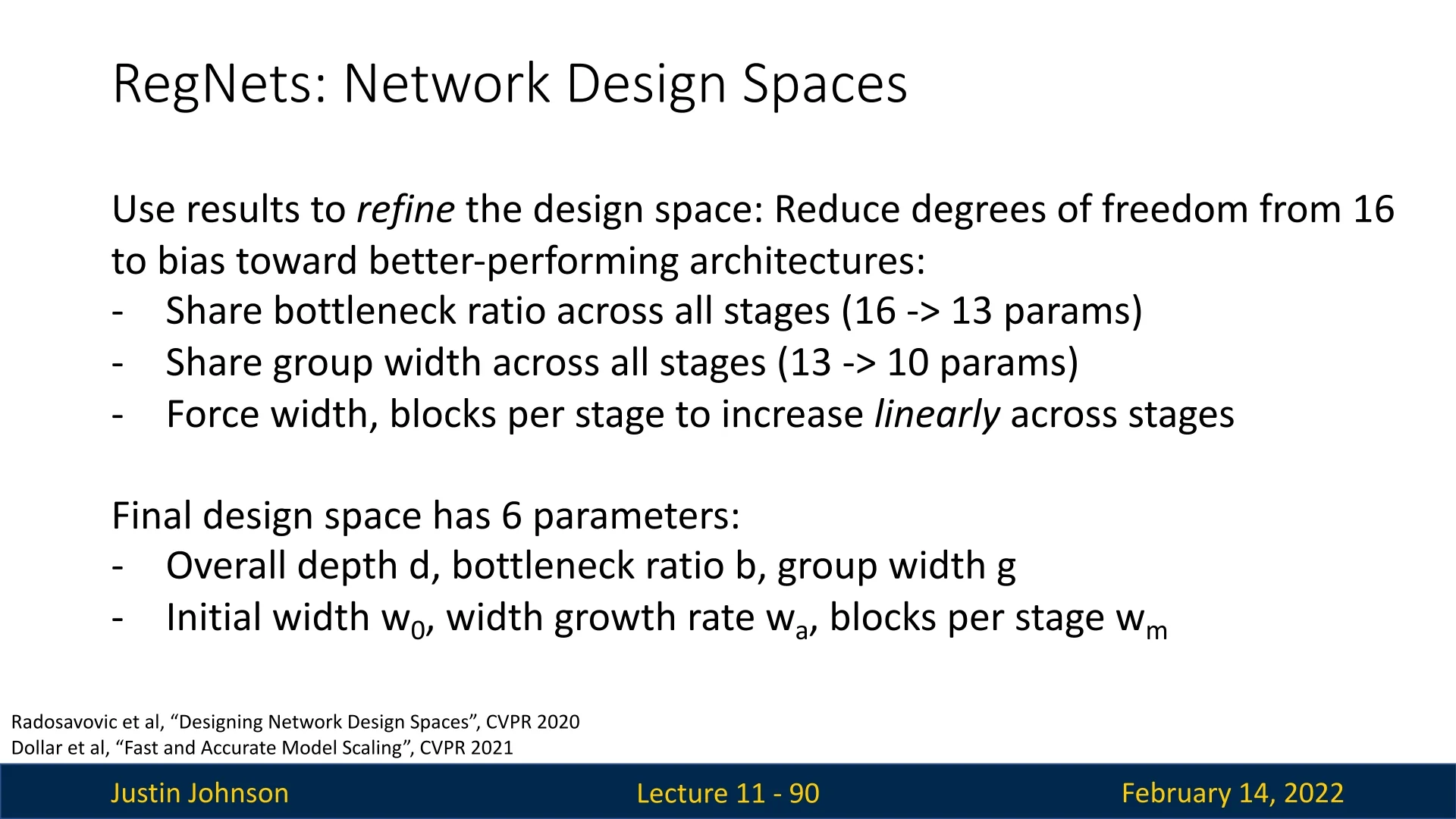

- RegNet focuses on designing regular, scalable CNN families whose width and depth follow simple rules; under similar FLOP budgets, RegNet models have been reported to match EfficientNet-level accuracy while requiring up to \(\sim \)5\(\times \) fewer training iterations.

We will revisit these architectures in later chapters. For now, ShuffleNet serves as a key example of how seemingly simple operations—grouped convolutions plus a differentiable channel permutation—can dramatically improve the efficiency of convolutional networks while maintaining strong accuracy on large-scale benchmarks.

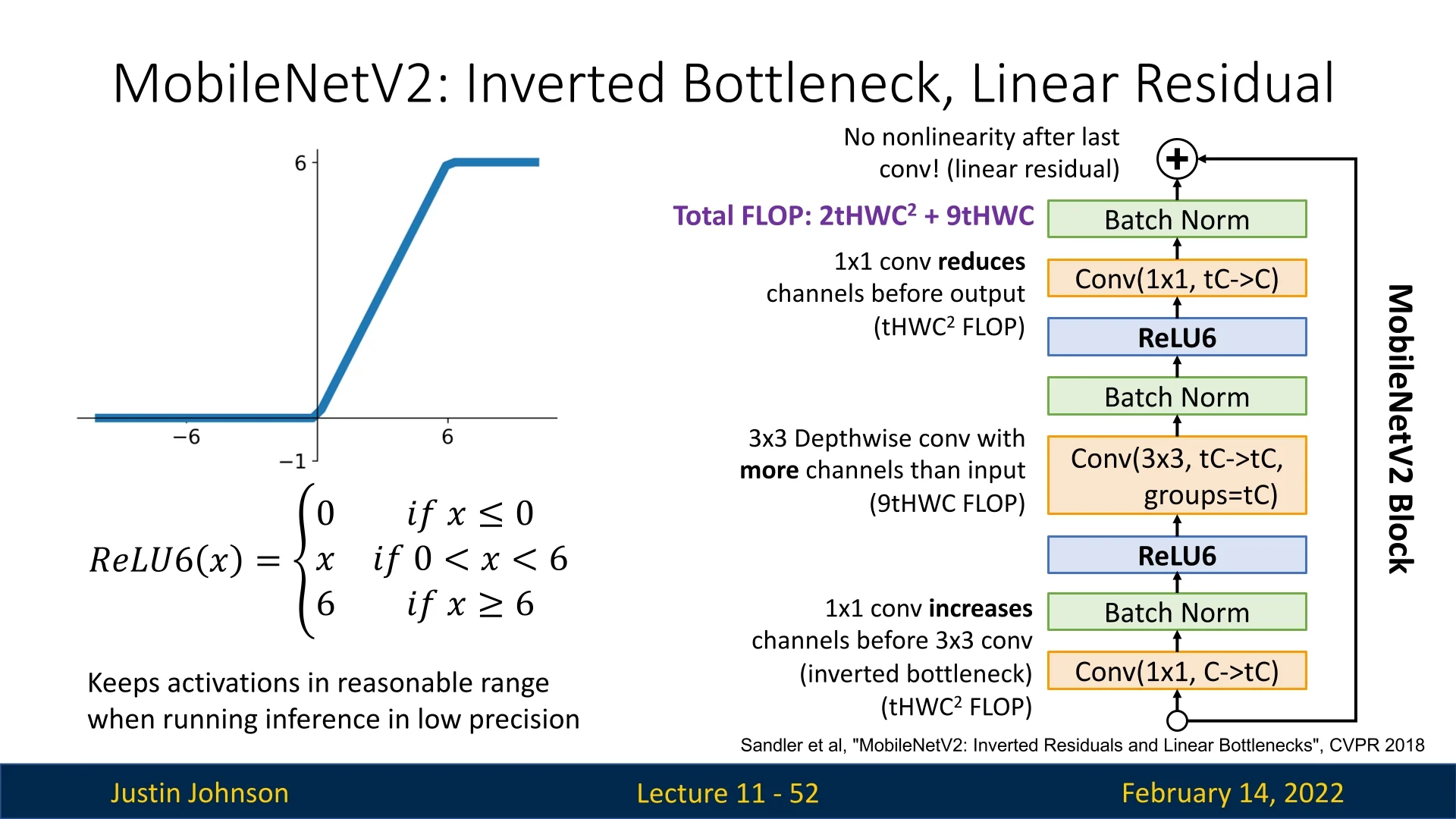

11.5.3 MobileNetV2: Inverted Bottleneck and Linear Residual

Motivation: When to Apply Non-Linearity?

MobileNetV2 [547] builds upon MobileNetV1’s depthwise-separable design but

further refines how and where non-linear activations are applied. The

key insight is that applying a non-linearity such as ReLU at the wrong

stage—particularly after reducing the channel dimension—can irreversibly

discard useful information.

Instead, MobileNetV2 proposes:

“Apply non-linearity in the expanded, high-dimensional space before projecting back linearly to a lower-dimensional representation.”

This ensures that the most expressive transformations occur in a rich, high-dimensional space, and the final projection back to a lower-dimensional space does not suffer from information loss due to ReLU-induced zeroing-out of channels.

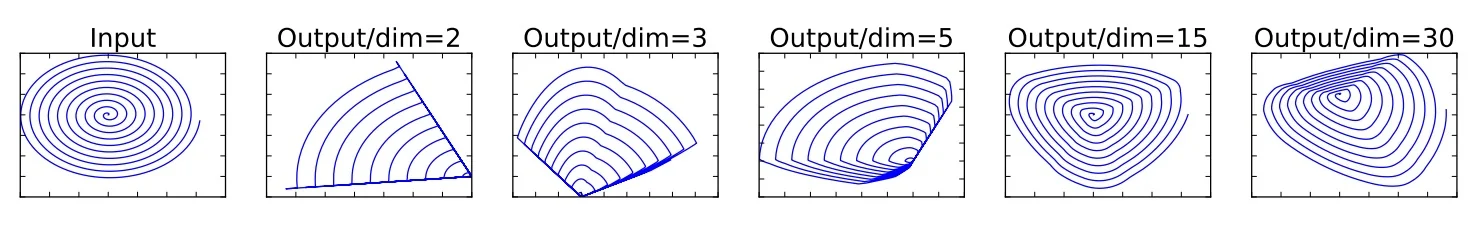

Understanding Feature Representations and Manifolds A convolutional layer with an output shape of \( h \times w \times d \) can be interpreted as a grid of \( h \times w \) spatial locations, where each location contains a \( d \)-dimensional feature vector. Although this representation is formally \( d \)-dimensional, empirical evidence suggests that the manifold of interest—the meaningful variation within these activations—often resides in a much lower-dimensional subset. In other words, not all \( d \) dimensions contain independently useful information; instead, they are highly correlated, meaning they effectively form a low-dimensional structure within the high-dimensional activation space.

ReLU and Information Collapse Applying ReLU in a low-dimensional subspace can lead to an irreversible loss of information. To illustrate this, consider the following experiment:

- A 2D spiral is embedded into an \(n\)-dimensional space using a random matrix transformation \(T\).

- A ReLU activation is applied in this \(n\)-dimensional space.

- The transformed data is then projected back to 2D using \(T^{-1}\).

- When \(n\) is small (e.g., \(n=2\) or \(n=3\)), ReLU distorts or collapses the manifold, as important information is lost when negative values are clamped to zero.

- When \(n\) is large (\(n \geq 15\)), the manifold remains well-preserved, as the high-dimensional space allows the ReLU transformation to retain sufficient structure.

This experiment highlights a key principle: non-linearity should be applied in a sufficiently high-dimensional space to avoid information collapse. This directly motivates the MobileNetV2 design, which introduces an inverted residual block.

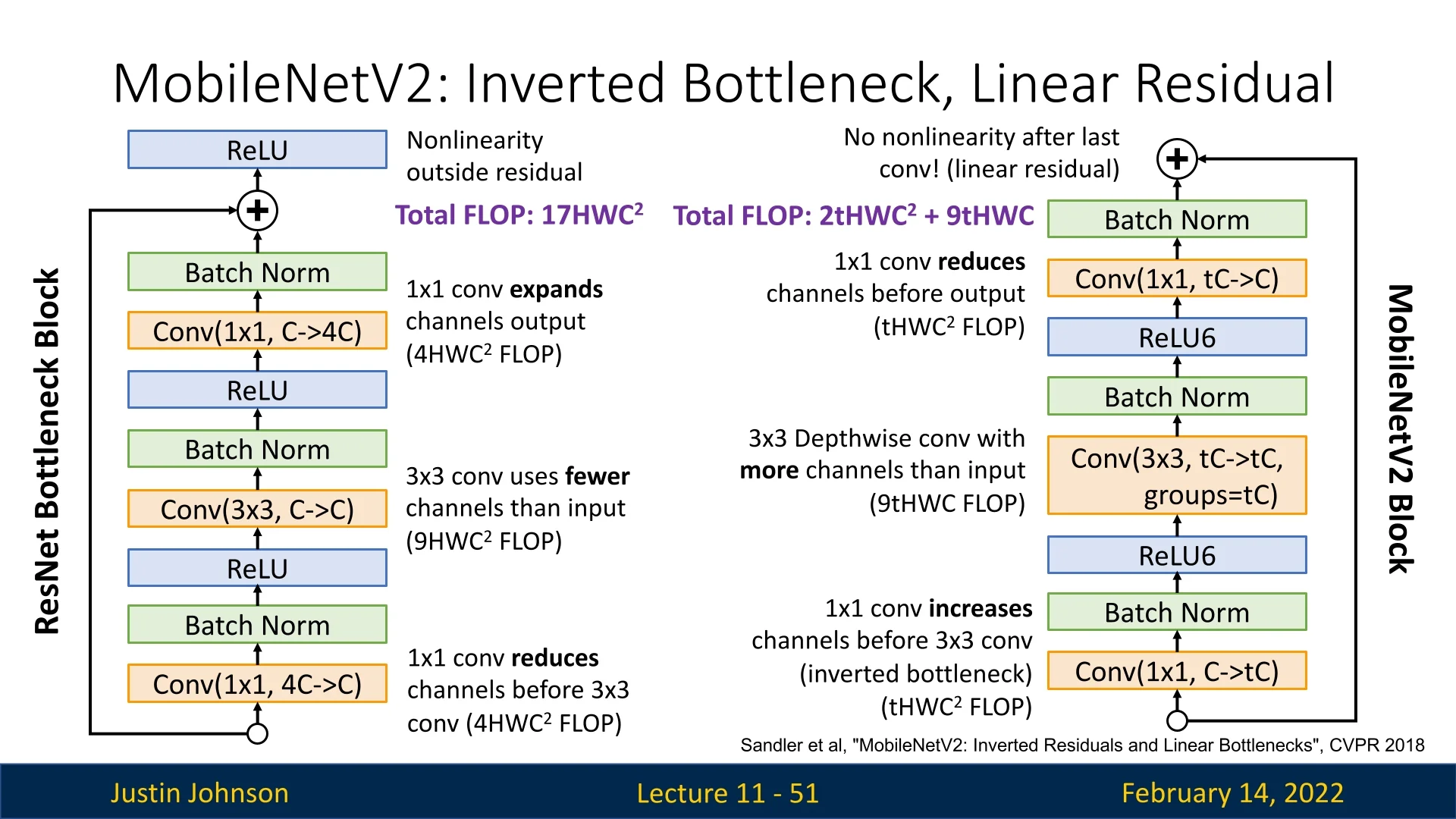

The MobileNetV2 Block: Inverted Residuals and Linear Bottleneck

Why “Inverted Residual”?

Traditional residual blocks, such as those in ResNet, transform wide feature

representations into a narrow bottleneck before expanding back. MobileNetV2

inverts this pattern: it starts with a narrow representation, expands it using

a pointwise convolution, applies a depthwise convolution, then projects it

back to a narrow representation. This is why it is called an inverted

residual.

Detailed Block Architecture Each MobileNetV2 block consists of:

- 1.

- Expansion (\(1\times 1\) conv + ReLU6): Increases the channel dimension by an expansion factor \(t\) (typically \(t=6\)), allowing non-linearity to operate in a richer space.

- 2.

- Depthwise Conv (\(3\times 3\) + ReLU6): Efficiently captures spatial features with minimal cross-channel computation.

- 3.

- Projection (\(1\times 1\) conv, no ReLU): Reduces back to the original (narrow) dimension. This step is linear to prevent information loss due to non-linearity.

- 4.

- Residual Connection: If the input and output shapes match (same spatial size and number of channels), a skip connection adds the input to the output.

ReLU6 and Its Role in Low-Precision Inference

Definition and Motivation

MobileNetV2 employs ReLU6 instead of standard ReLU, defined as: \[ \mathrm {ReLU6}(x)\;=\;\min \bigl (\max (0,\,x),\,6\bigr ). \] This

choice was primarily motivated by:

- Activation Range Constraint: Since ReLU6 clamps values between 0 and 6, it prevents extremely large activations that could dominate later layers, improving numerical stability.

- Fixed-Point Quantization Stability: In 8-bit integer arithmetic, numbers are typically represented with limited dynamic range. By keeping activations within a well-bounded range, ReLU6 reduces precision loss when mapping from floating-point to integer representation.

Practical Observations and Alternatives Later research [305] found that:

- ReLU6 does not always improve quantization. While it was originally intended to make 8-bit inference more robust, in practice, most modern quantization techniques can handle ReLU just as well.

- ReLU can sometimes outperform ReLU6. In particular, in cases where higher activation values play a role in separating decision boundaries, the strict upper bound of ReLU6 can be detrimental.

As a result, later architectures such as MobileNetV3 have moved back to using standard ReLU.

Why is the Inverted Block Fitting to Efficient Networks?

At first glance, temporarily expanding the channel dimension before processing and then narrowing it again seems to introduce additional computational cost compared to a straightforward bottleneck or MobileNetV1’s depthwise-separable design. However, MobileNetV2 often achieves higher accuracy at similar or only slightly higher FLOPs due to the following key factors:

1. Depthwise Convolutions Maintain Low Computational Cost As in MobileNetV1, each \(3\times 3\) depthwise convolution operates on each channel separately, reducing computational complexity from: \[ \mathcal {O}(k^2 \cdot \mbox{height} \cdot \mbox{width} \cdot \mbox{channels_in} \times \mbox{channels_out}) \] to: \[ \mathcal {O}(k^2 \cdot \mbox{height} \cdot \mbox{width} \cdot \mbox{channels_in}) \] This ensures that most of the FLOPs in each block remain low despite the temporary expansion of channels.

2. Moderate Expansion Factor \((t)\) Balances Efficiency The expansion factor \(t\) determines how much the channel dimension increases inside the block. In practice, \(t=6\) is commonly used, striking a balance between expressivity and computational efficiency. This expansion allows non-linear transformations (via ReLU) to operate in a higher-dimensional space, reducing the risk of losing critical channels while ensuring that the final projection does not incur excessive overhead.

3. Comparison to MobileNetV1 The computational cost of a single block in each architecture is:

- MobileNetV1: \(\mathcal {O}((9C + C^2)HW)\)

- MobileNetV2: \(\mathcal {O}((9tC + 2tC^2)HW)\) per block, due to channel expansion.

Although MobileNetV2 appears to introduce additional cost, the overall network remains efficient because:

- MobileNetV2 has fewer layers than MobileNetV1. While the original MobileNetV1 consists of 28 layers, MobileNetV2 reduces this number to 17.

- MobileNetV2 has wider representations per layer. Since each block expands channels internally, fewer layers are needed to reach a comparable expressive power.

- The cost gap between the two architectures decreases as the channel count increases. Specifically, for large \(C\), the cost of MobileNetV1 (which has \(\mathcal {O}(C^2)\) terms) becomes comparable to the cost of MobileNetV2 with moderate expansion (\(t=6\)).

Empirically, MobileNetV2 achieves higher accuracy per FLOP compared to MobileNetV1, making the trade-off worthwhile.

4. Comparison to ResNet Bottleneck Blocks While MobileNetV2 is inspired by ResNet’s bottleneck design, the computational costs differ:

- ResNet bottleneck: \(\mathcal {O}(17HWC^2)\)

- MobileNetV2 bottleneck: \(\mathcal {O}(2tHWC^2 + 9tHWC)\)

For moderate values of \(t\), e.g., \(t=6\), we have: \[ \mbox{MobileNetV2 is more efficient than ResNet if: } 54HWC < 5HWC^2 \] At high channel counts, the computational gap reduces significantly. In some cases, MobileNetV2 blocks can even be more efficient than ResNet bottlenecks.

5. Linear Bottleneck Preserves Subtle Features Unlike traditional residual connections, MobileNetV2 omits ReLU in the final projection layer. This ensures that small but useful activations are not lost when projecting back to the lower-dimensional space. This is particularly important in low-dimensional feature spaces where aggressive non-linearity can collapse valuable information.

Summary Although the MobileNetV2 block seems computationally heavier than MobileNetV1 on a per-block basis, the overall network-level architecture is more efficient because:

- It requires fewer total layers.

- Fewer downsampling stages are used in deeper layers.

- It achieves significantly better accuracy at a similar FLOP budget.

MobileNetV2 Architecture and Performance

Network Structure MobileNetV2 consists of:

| Input | Operator | #Repeats | Expansion | Output Channels |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| \(224^2 \times 3\) | \(3\times 3\) Conv (stride 2) | 1 | – | 32 |

| \(112^2 \times 32\) | Inverted Residual Block | 1 | 1 | 16 |

| \(112^2 \times 16\) | Inverted Residual Block | 2 | 6 | 24 |

| \(56^2 \times 24\) | Inverted Residual Block | 3 | 6 | 32 |

| \(28^2 \times 32\) | Inverted Residual Block | 4 | 6 | 64 |

| \(14^2 \times 64\) | Inverted Residual Block | 3 | 6 | 96 |

| \(14^2 \times 96\) | Inverted Residual Block | 3 | 6 | 160 |

| \(7^2 \times 160\) | Inverted Residual Block | 1 | 6 | 320 |

| \(7^2 \times 320\) | \(1\times 1\) Conv | 1 | – | 1280 |

Comparison to MobileNetV1, ShuffleNet, and NASNet

Efficiency and Accuracy Trade-offs

MobileNetV2 refines MobileNetV1’s depthwise-separable design and

introduces inverted residuals and linear bottlenecks, leading to

better efficiency-accuracy trade-offs. Compared to alternative lightweight

architectures, it strikes a balance between computational cost and real-world

deployability.

| Network | Top-1 Acc. (%) | Params (M) | MAdds (M) | CPU Time (ms) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MobileNetV1 | 70.6 | 4.2M | 575M | 113ms |

| ShuffleNet (1.5×) | 71.5 | 3.4M | 292M | - |

| ShuffleNet (2×) | 73.7 | 5.4M | 524M | - |

| NASNet-A | 74.0 | 5.3M | 564M | 183ms |

| MobileNetV2 | 72.0 | 3.4M | 300M | 75ms |

| MobileNetV2 (1.4×) | 74.7 | 6.9M | 585M | 143ms |

Key Observations:

- MobileNetV2 vs. MobileNetV1: MobileNetV2 achieves 1.4% higher accuracy while reducing Multiply-Adds by nearly 50%. This efficiency gain comes from inverted residuals and linear bottlenecks, which prevent feature collapse in low-dimensional spaces and allow to reduce the number of layers significantly while retaining representational power.

-

MobileNetV2 vs. ShuffleNet: ShuffleNet (2×) achieves a slightly higher 73.7% accuracy but at a higher computational cost (524M Multiply-Adds vs. 300M for MobileNetV2). MobileNetV2 remains more widely used due to better hardware support for its depthwise operations.

- MobileNetV2 vs. NASNet-A: NASNet-A, designed via Neural Architecture Search (NAS), achieves the highest accuracy (74.0%) but is significantly slower (183ms inference time vs. 75ms for MobileNetV2).

Motivation for NAS and MobileNetV3

While MobileNetV2 optimizes manual architecture design, NASNet-A highlights

the potential of automated architecture search to find even better

efficiency-accuracy trade-offs. However, its high computational cost motivates

MobileNetV3, which builds on MobileNetV2 while incorporating NAS

techniques to optimize block structures, activation functions, and expansion

ratios for real-world deployment.

The next section explores NAS and MobileNetV3, bridging the gap between handcrafted and automatically optimized architectures.

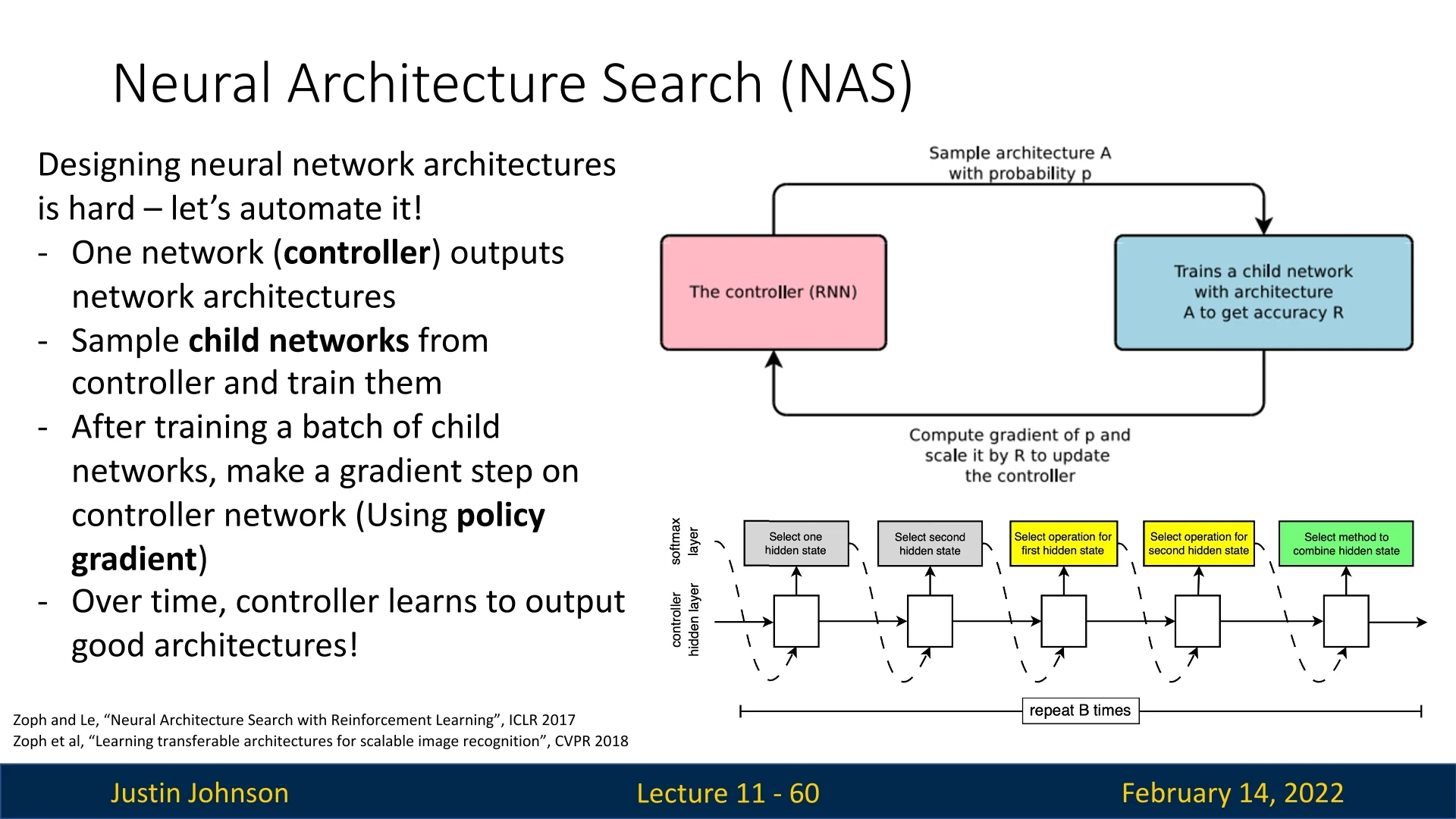

11.5.4 Neural Architecture Search (NAS) and MobileNetV3

Neural Architecture Search (NAS): Automating Architecture

Design

Designing neural network architectures is a challenging and time-consuming task.

Neural Architecture Search (NAS) [812, 813] aims to automate this process by using a

controller network that learns to generate optimal architectures through

reinforcement learning.

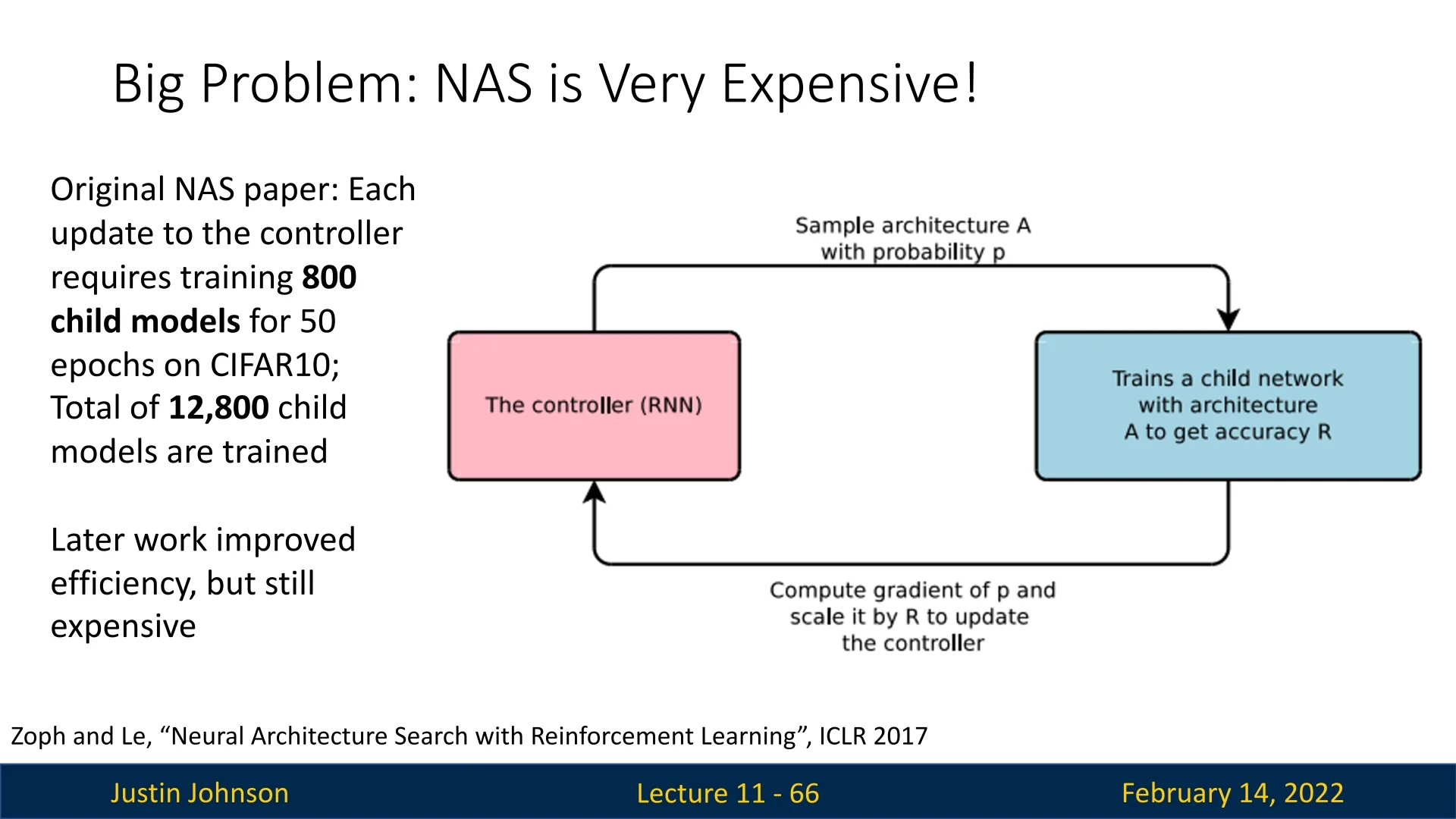

How NAS Works? Policy Gradient Optimization

Neural Architecture Search (NAS) uses a controller network to generate candidate architectures, which are then evaluated to improve the search strategy. However, the challenge is that architectural search is non-differentiable. It is not possible to directly compute gradients for better architectures. Instead, NAS relies on policy gradient optimization, a reinforcement learning (RL) technique, to update the controller.

What is a Policy Gradient? In reinforcement learning, an agent interacts with an environment and takes actions based on a learned policy to maximize a reward. The policy is typically parameterized by a neural network, and a policy gradient method updates these parameters by computing gradients with respect to expected future rewards.

For NAS:

- The controller network acts as the RL agent, outputting architectural decisions (e.g., filter sizes, number of layers).

- The child networks sampled from the controller act as the environment; they are trained and evaluated on a dataset.

- The reward function is defined based on the validation accuracy of the sampled child networks.

Updating the Controller Using Policy Gradients NAS applies the REINFORCE algorithm [693] to update the controller network: \begin {equation} \nabla J(\theta ) = \mathbb {E} \left [ \sum _{t=1}^{T} \nabla _{\theta } \log p(a_t | \theta ) R \right ], \end {equation} where:

- \( \theta \) are the controller’s parameters.

- \( a_t \) represents architectural choices (e.g., layer types, kernel sizes).

- \( R \) is the reward (child network validation accuracy).

Intuitively, this means:

- 1.

- Sample an architecture.

- 2.

- Train it and measure its accuracy.

- 3.

- Update the controller to reinforce architectural decisions that led to better accuracy.

Over time, NAS converges to high-performing architectures.

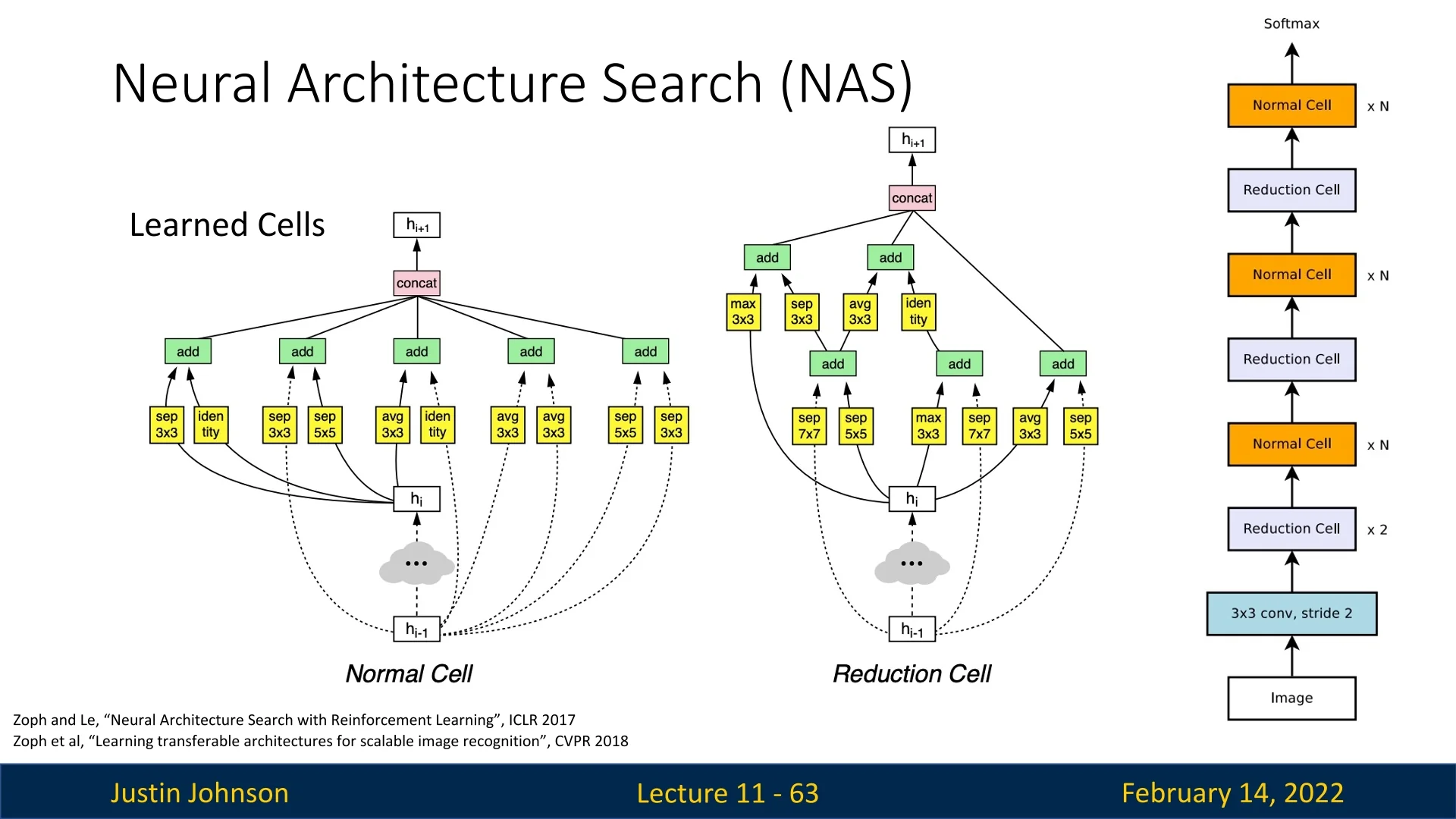

Searching for Reusable Block Designs Rather than searching for an entire architecture from scratch, NAS focuses on identifying efficient reusable blocks, which can be stacked to construct a full network. The search space consists of various operations, including:

- Identity

- \(1\times 1\) convolution

- \(3\times 3\) convolution

- \(3\times 3\) dilated convolution

- \(1\times 7\) followed by \(7\times 1\) convolution

- \(1\times 3\) followed by \(3\times 1\) convolution

- \(3\times 3\), \(5\times 5\), or \(7\times 7\) depthwise-separable convolutions

- \(3\times 3\) average pooling

- \(3\times 3\), \(5\times 5\), or \(7\times 7\) max pooling

NAS identifies two primary block types:

- Normal Cell: Maintains the same spatial resolution.

- Reduction Cell: Reduces spatial resolution by a factor of \(2\).

These cells are then combined in a regular pattern to construct the final architecture.

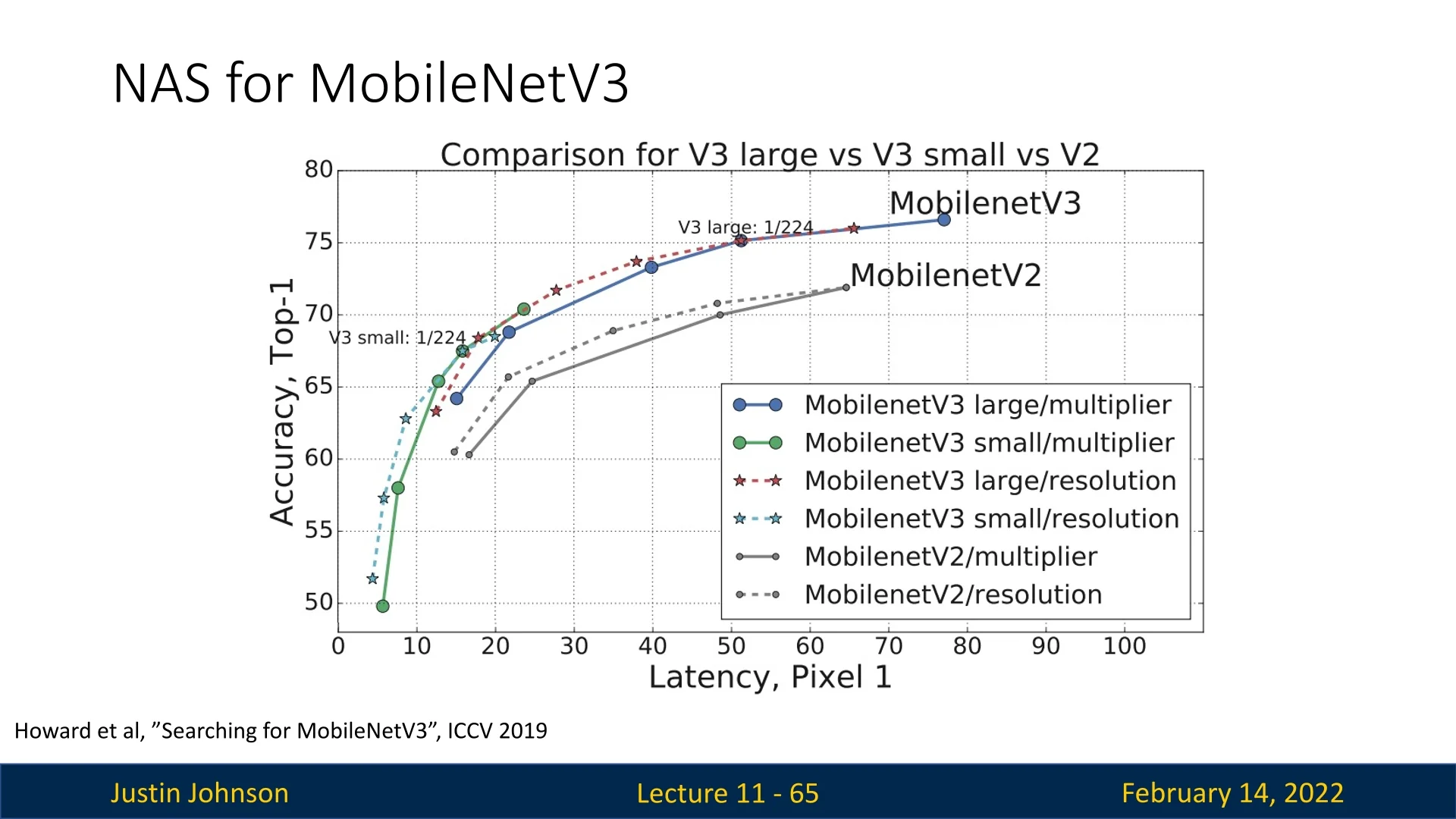

MobileNetV3: NAS-Optimized Mobile Network

Motivation and Evolution from MobileNetV2.

MobileNetV3 [230] builds upon MobileNetV2 by leveraging NAS to further

optimize key architectural choices. It incorporates:

- EfficientNet-style NAS search to refine block selection and expansion ratios.

- Swish-like activation function (h-swish) to improve non-linearity efficiency.

- Squeeze-and-Excitation (SE) modules in some layers to improve channel-wise attention.

- Smaller and optimized depthwise convolutions, reducing computational cost while maintaining expressiveness.

The MobileNetV3 Block Architecture and Refinements

MobileNetV3 [230] was developed using NAS, which optimized its block structure, activation functions, and efficiency improvements.

Structure of the MobileNetV3 Block The core MobileNetV3 block builds upon the MobileNetV2 inverted residual block but introduces:

- Squeeze-and-Excitation (SE) modules to enhance important features.

- h-swish activation instead of ReLU6 for better non-linearity.

- Smaller depthwise convolutions to reduce computation.

Differences from Previous MobileNet Blocks

- MobileNetV1 Used standard depthwise separable convolutions.

- MobileNetV2 Introduced the inverted residual block and linear bottlenecks.

- MobileNetV3 Enhances MobileNetV2 with NAS-optimized activation functions and attention mechanisms.

Why is MobileNetV3 More Efficient?

At first glance, MobileNetV3 may seem computationally more expensive than MobileNetV2 since it builds upon the same inverted residual block while introducing additional mechanisms like squeeze-and-excitation (SE). However, it is actually more efficient due to several optimizations discovered through NAS.

Key Optimizations That Improve Efficiency

- Neural Architecture Search (NAS) Optimization: NAS optimizes layer types, kernel sizes, and expansion ratios to minimize latency on real-world mobile hardware. Rather than using a fixed design like MobileNetV2, NAS learns the most efficient way to balance depthwise separable convolutions, SE blocks, and activation functions.

- Selective Use of SE Blocks: While SE blocks add computation, NAS only places them in layers where they provide the most accuracy gain per FLOP. MobileNetV2 did not use the channel-attention mechanism at all, whereas MobileNetV3 strategically incorporates SE only in certain depthwise layers, preventing unnecessary overhead.

- h-swish Activation: ReLU6 was initially introduced in MobileNetV2 for quantization robustness but has a hard threshold at 6, limiting its expressiveness. MobileNetV3 replaces it with h-swish, approximates the smoothness of Swish (more computationally efficient): \begin {equation} \mbox{h-swish}(x) = x \cdot \frac {\max (0, \min (x+3, 6))}{6}. \end {equation} This activation function improves accuracy and stability with little extra computational cost.

- Fewer Depthwise Layers, Higher Efficiency: NAS found that some depthwise convolutions in MobileNetV2 were redundant. By reducing the number of depthwise layers in specific parts of the network while slightly increasing the expansion ratio elsewhere, MobileNetV3 achieves a better accuracy-FLOP tradeoff.

- Better Parallelism and Memory Access Efficiency: MobileNetV3 is designed to maximize memory access efficiency (avoiding network fragmentation) and parallel execution on ARM-based chips.

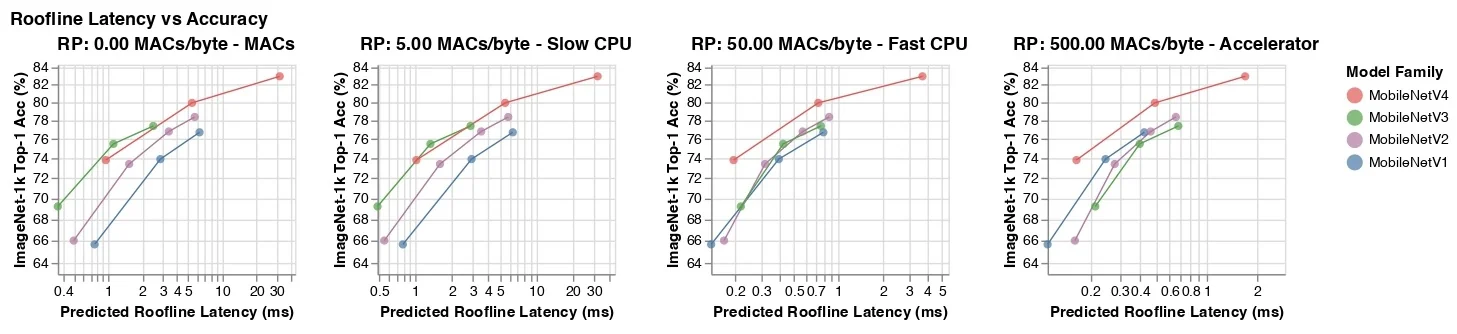

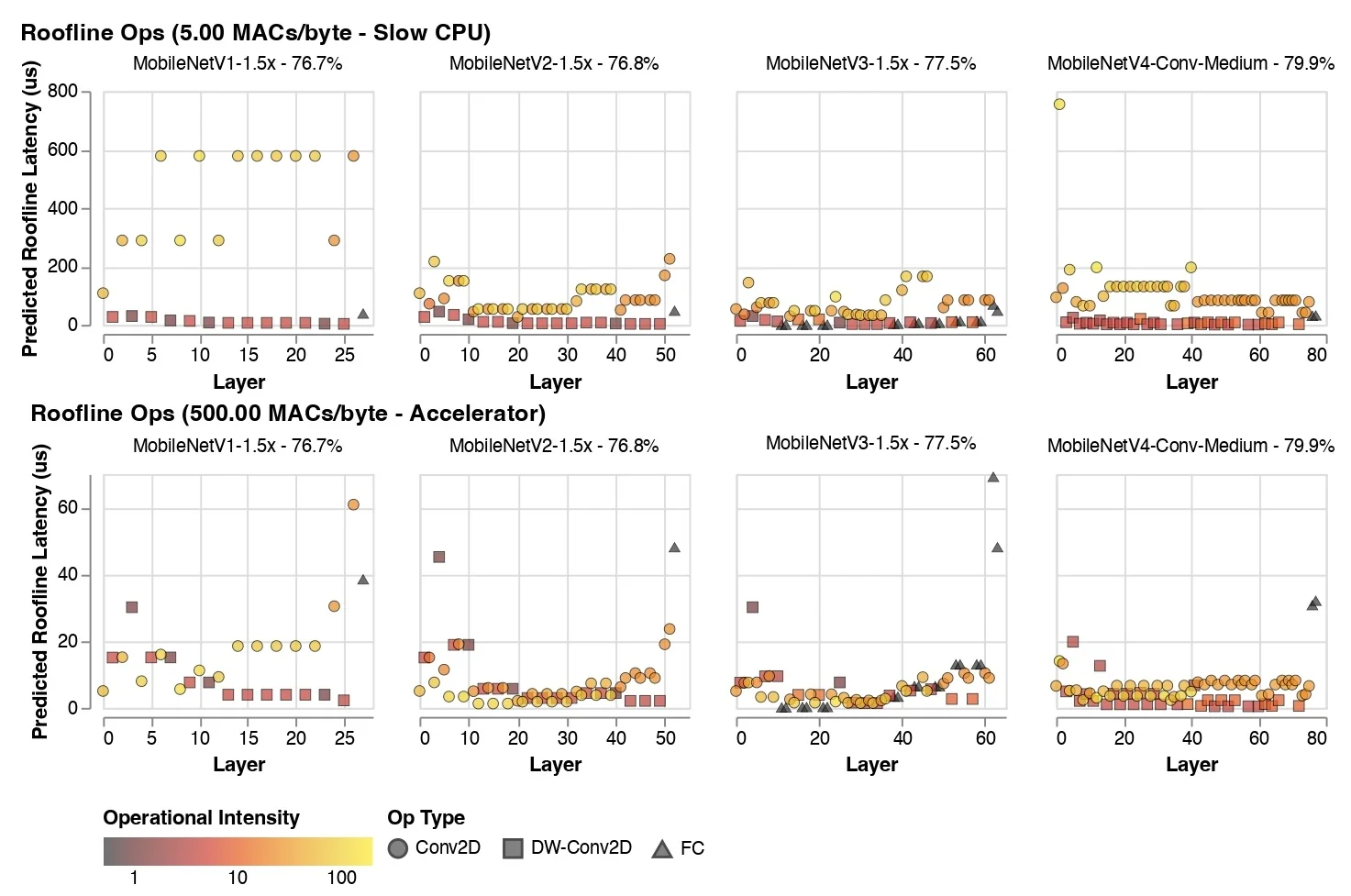

Empirical Comparison of MobileNetV3 MobileNetV3 introduces architecture search and network-level optimizations that make it both faster and more accurate than its predecessors.

| Family | Variant | Top-1 Acc. (%) | MAdds (M) | Latency (ms) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MobileNetV1 [229] | 1.0 MobileNet-224 | 70.6 | 569 | 119 |

| MobileNetV2 [547] | 1.0 MobileNetV2-224 | 72.0 | 300 | 72 |

| MobileNetV3 [230] | Large 1.0 | 75.2 | 219 | 51 |

| MobileNetV3 [230] | Small 1.0 | 67.4 | 66 | 15.8 |

| MnasNet [601] | A1 (baseline) | 75.2 | 312 | 70 |

| ProxylessNAS [61] | GPU-targeted | 74.6 | 320 | 78 |

MobileNetV3-Large matches the accuracy of MnasNet-A1 while using 30% fewer multiply-add operations and achieving over 25% lower latency. Compared to MobileNetV2, it improves Top-1 accuracy by more than 3%, with a 27% reduction in computation and substantially lower inference time—making it an attractive choice for high-performance mobile inference.

The Computational Cost of NAS and Its Limitations

Despite its success in automating architecture search, Neural Architecture Search (NAS) is computationally expensive, making it impractical for many real-world applications.

- Training Thousands of Models: NAS relies on evaluating a vast number of candidate architectures, requiring immense computational resources.

- Slow Policy Gradient Optimization: Unlike standard gradient-based training, NAS often uses reinforcement learning techniques, such as policy gradients, which require many optimization steps to converge.

- Fragmented and Inefficient Architectures: NAS-generated networks may be highly fragmented, reducing their parallel execution efficiency on modern hardware.

- High Parallelism is Often Inefficient: While NAS models aim to maximize hardware utilization, excessive fragmentation and complex layer dependencies can slow down inference.

While NAS has produced strong models like MobileNetV3, its computational cost remains a major bottleneck. This motivates alternative approaches that focus on efficiency without requiring exhaustive search.

ShuffleNetV2 and Practical Design Rules

Why ShuffleNetV2? Whereas ShuffleNetV1 focused on reducing theoretical FLOPs via group convolutions and channel shuffling, ShuffleNetV2 [408] reorients the goal toward real-world efficiency. This shift stems from a key observation: FLOPs are a poor predictor of actual inference time on mobile and embedded hardware. In practice, performance is often dominated by the memory access cost (MAC)—that is, the latency and bandwidth required to move data between memory and compute units, not the number of multiply–accumulate operations.

Because modern mobile SoCs (System-on-Chips) are highly parallel but memory-bound, factors like tensor fragmentation, channel imbalance, and excessive branching can bottleneck throughput. ShuffleNetV2 addresses these bottlenecks through four pragmatic design rules that align the network’s dataflow with hardware constraints, yielding smoother parallelism and lower latency.

Four Key Guidelines for Practical Efficiency The authors propose four guidelines—each derived from profiling real devices—to ensure that architectural efficiency translates into real speedups:

- 1.

- G1: Equal channel widths minimize memory access cost. Maintaining consistent channel dimensions across layers minimizes intermediate buffering and reindexing, reducing the number of cache misses and memory stalls.

- 2.

- G2: Excessive group convolutions raise memory access cost. While group convolutions reduce FLOPs, they fragment tensors into small sub-blocks. Each sub-block requires independent reads and writes, increasing data movement and synchronization overhead.

- 3.

- G3: Excessive network fragmentation hinders parallelism. Architectures that repeatedly split and merge feature maps (e.g., multi-path or highly branched designs) prevent hardware from exploiting full parallelism, since many cores must wait for partial results.

- 4.

- G4: Element-wise operations are non-negligible. Operations such as Add, ReLU, and channel shuffling have small FLOP counts but non-trivial memory and kernel-launch costs. Minimizing or fusing them improves latency.

From ShuffleNetV1 to ShuffleNetV2 ShuffleNetV1 achieved strong FLOP reductions but violated several of these principles in practice:

- The heavy use of grouped \(1\times 1\) convolutions (often with large \(g\)) increased MAC (violating G2).

- The frequent split–shuffle–concat sequences introduced fragmentation (violating G3).

ShuffleNetV2 remedies this with a streamlined design:

- It removes grouping from most \(1\times 1\) convolutions (reducing G2 overhead).

- It enforces uniform channel splits (satisfying G1) and applies only one shuffle after concatenation (reducing G4).

- It simplifies the data path into a near-linear flow with minimal branching (satisfying G3).

The ShuffleNetV2 Unit: Architecture and Intuition The new ShuffleNetV2 block (Figure 11.30c) is carefully structured to follow these principles:

- 1.

- Channel Split: The input tensor (with \(C\) channels) is evenly split into two halves (\(C/2\) each). One half forms a lightweight identity branch, and the other half forms a processing branch.

- 2.

- Processing Branch: The active half passes through a standard (non-grouped) \(1\times 1\) convolution, followed by a \(3\times 3\) depthwise convolution (DWConv) and another \(1\times 1\) convolution. All layers maintain constant channel width (\(C/2\)), adhering to G1. Removing group convolutions and keeping uniform channel widths directly lowers MAC and fragmentation.

- 3.

- Concatenation and Shuffle: The processed output and the untouched identity branch are concatenated, restoring the total channel count to \(C\). A single channel shuffle then mixes the two halves, ensuring that subsequent blocks receive blended information without needing multiple permutations.

- 4.

- Stride-2 Variant: For downsampling (Figure 11.30d), both branches are active. The main branch applies depthwise convolution with stride 2, and the shortcut branch uses a parallel \(3\times 3\) depthwise convolution followed by concatenation. This doubles channel count while halving spatial resolution, avoiding extra addition or pooling operations.

This design nearly eliminates redundant memory movement while retaining strong feature interaction—demonstrating that well-structured simplicity can outperform complex multi-branch patterns.

Performance vs. MobileNetV3 Although ShuffleNetV2 achieves excellent hardware efficiency and latency, it does not always surpass MobileNetV3 in accuracy at equivalent FLOP budgets. Key reasons include:

- Inverted Bottlenecks (MobileNetV3): MobileNetV3 expands and compresses channels asymmetrically, seemingly violating G1’s uniformity rule. However, its NAS-optimized expansions and fusions exploit hardware more effectively, offsetting theoretical inefficiencies.

- Neural Architecture Search (NAS): While ShuffleNetV2 follows fixed rules, MobileNetV3 uses NAS to explore exceptions—sometimes deliberately introducing non-uniform widths or SE-blocks that slightly increase MAC but improve accuracy and speed once fused.

- Real-world Latency: On mobile CPUs and NPUs, MobileNetV3’s fused inverted residual blocks often run 10–15% faster than ShuffleNetV2, thanks to reduced kernel launches and optimized operator fusion.

Despite this, ShuffleNetV2’s four design rules remain highly influential. They codified practical guidelines for mapping convolutional networks efficiently onto real hardware—guidelines that informed both NAS search spaces and the design of later lightweight models such as MobileNetV3 and EfficientNet-Lite.

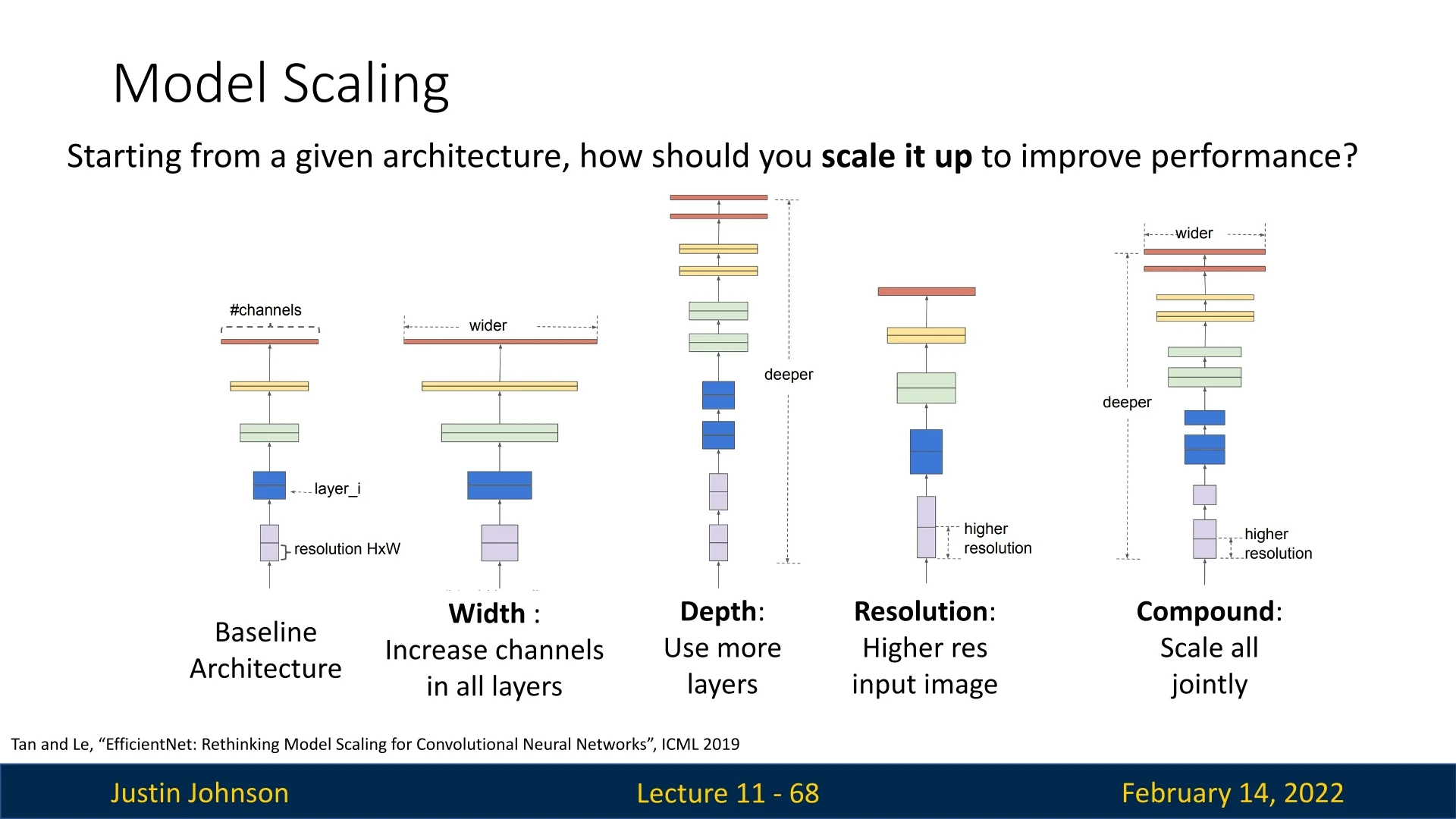

The Need for Model Scaling and EfficientNets

Beyond Hand-Designed and NAS-Optimized Models While manually designed architectures (e.g., ShuffleNetV2) and NAS-optimized networks (e.g., MobileNetV3) have driven major advancements in efficiency, there is still room for improvement. The search for better trade-offs between accuracy and computational cost has led researchers to a fundamental question:

Instead of searching for entirely new architectures, can we systematically scale existing models to achieve optimal efficiency?

Rather than focusing solely on designing better building blocks or running expensive NAS procedures, an alternative approach emerged: scaling existing models in a structured manner. Scaling a model can involve increasing:

- Depth: Adding more layers to increase representational power.

- Width: Expanding the number of channels per layer.

- Resolution: Using larger input images to capture finer details.

However, scaling any single dimension in isolation often leads to suboptimal results. Increasing depth alone may result in diminishing returns, while scaling width or resolution independently can make models inefficient. Instead, we need a principled way to scale these three dimensions together.

Introducing EfficientNet To address this challenge, EfficientNet [600] was proposed, leveraging a compound scaling approach that jointly optimizes depth, width, and resolution in a balanced way. By using a carefully tuned scaling coefficient, EfficientNet ensures that all three dimensions grow in harmony, yielding models that maximize accuracy while minimizing computational cost.

11.6 EfficientNet Compound Model Scaling

11.6.1 How Should We Scale a Model

Given a well-designed baseline architecture, a fundamental question arises:

How should we scale it up to improve performance while maintaining efficiency?

Common approaches to scaling include:

- Width Scaling: Increasing the number of channels per layer to capture more fine-grained features.

- Depth Scaling: Adding more layers to allow deeper feature extraction and better generalization.

- Resolution Scaling: Using higher-resolution images to enhance spatial feature learning.

The Problem with Independent Scaling Scaling only one of these dimensions leads to diminishing returns. Excessive depth can cause vanishing gradients, extreme width increases make models harder to optimize, and excessive resolution scaling results in computational inefficiencies. Instead, EfficientNet optimally balances all three.

Furthermore, the different scaling dimensions are not independent:

- For higher-resolution images, increasing depth allows larger receptive fields to capture similar features that include more pixels.

- Increasing width enhances fine-grained feature extraction, allowing more expressive representations.

- Simply scaling one dimension in isolation is inefficient—scaling must be done in a coordinated manner to maximize the model’s performance-to-cost ratio.

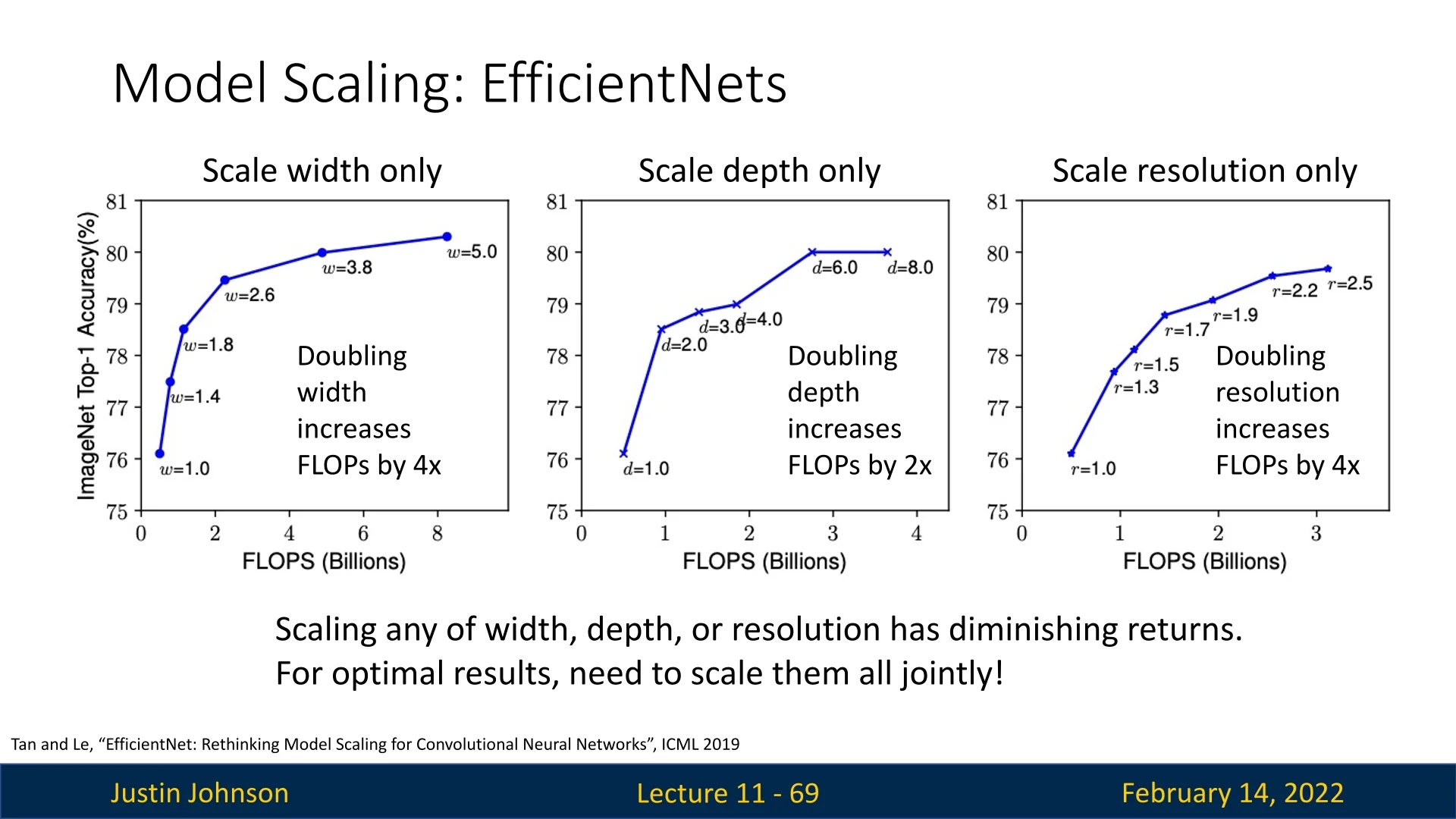

11.6.2 How EfficientNet Works

EfficientNet introduces a compound scaling approach, which systematically scales width, depth, and resolution together. Instead of arbitrary scaling, EfficientNet determines the best scaling ratios using an optimization process.

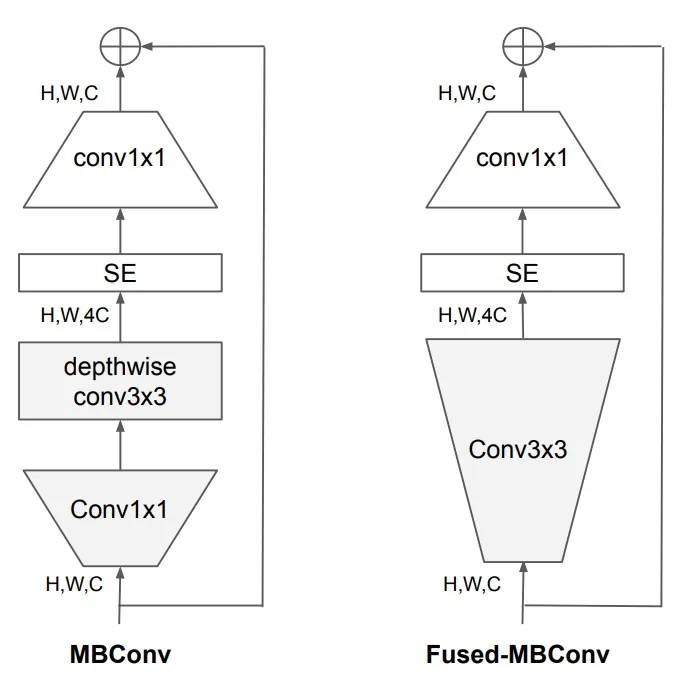

Step 1: Designing a Baseline Architecture A well-optimized small model, called EfficientNet-B0, is first discovered using NAS (Neural Architecture Search). This model incorporates:

- Depthwise separable convolutions to reduce computational cost while preserving spatial feature extraction.

- Inverted residual blocks (from MobileNetV2), also known as MBConv blocks, which employ a narrow-wide-narrow structure for efficient processing.

- Squeeze-and-Excitation (SE) blocks to enhance channel-wise feature selection, improving accuracy with minimal overhead.

| Stage | Operator | Resolution | # Channels | # Layers |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Conv3x3 | \(224 \times 224\) | 32 | 1 |

| 2 | MBConv1, k\(3\times 3\) | \(112 \times 112\) | 16 | 1 |

| 3 | MBConv6, k\(3\times 3\) | \(112 \times 112\) | 24 | 2 |

| 4 | MBConv6, k\(5\times 5\) | \(56 \times 56\) | 40 | 2 |

| 5 | MBConv6, k\(3\times 3\) | \(28 \times 28\) | 80 | 3 |

| 6 | MBConv6, k\(5\times 5\) | \(14 \times 14\) | 112 | 3 |

| 7 | MBConv6, k\(5\times 5\) | \(14 \times 14\) | 192 | 4 |

| 8 | MBConv6, k\(3\times 3\) | \(7 \times 7\) | 320 | 1 |

| 9 | Conv1x1 & Pooling & FC | \(7 \times 7\) | 1280 | 1 |

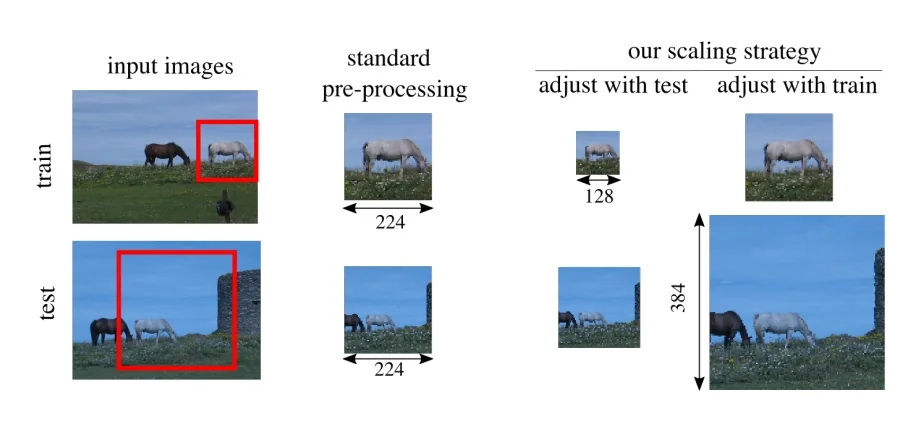

Step 2: Finding Optimal Scaling Factors Once the EfficientNet-B0 model is obtained, a grid search determines the best scaling factors for:

- \(\alpha \) (depth scaling).

- \(\beta \) (width scaling).

- \(\gamma \) (resolution scaling).

These scaling factors must satisfy the constraint: \[ \alpha \cdot \beta ^2 \cdot \gamma ^2 \approx 2 \] The reasoning behind this constraint is:

- It ensures that when we scale the model by a factor of \(\phi \), the total FLOPs increase by approximately \(2^\phi \), making it easier to monitor computational efficiency.

- This balance prevents over-scaling in one dimension while under-scaling in others, leading to more consistent improvements in accuracy per FLOP.

Through empirical search, the optimal values were found to be: \[ \alpha = 1.2, \quad \beta = 1.1, \quad \gamma = 1.15 \]

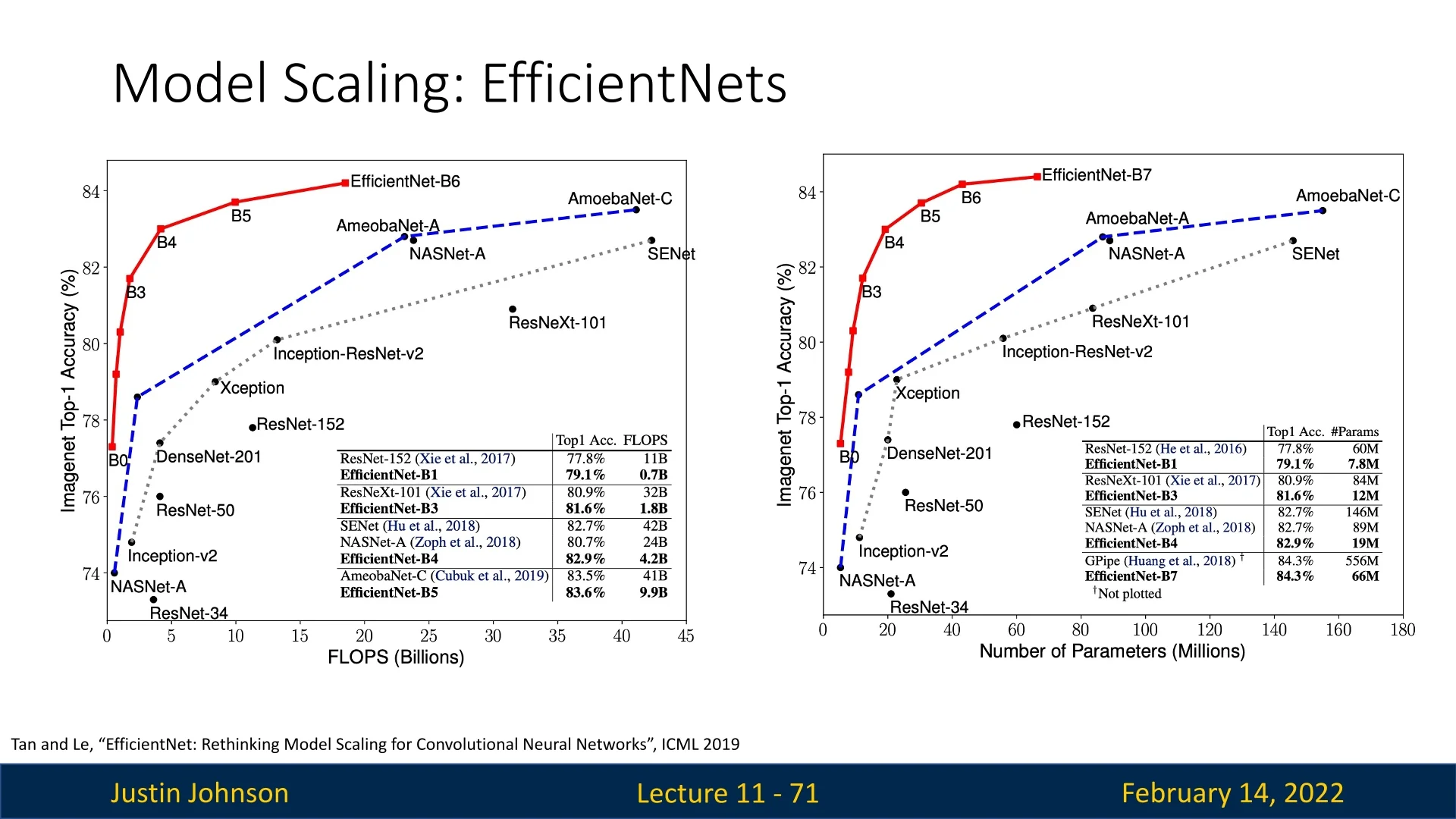

Step 3: Scaling to Different Model Sizes By applying these scaling factors to EfficientNet-B0 with different values of \(\phi \), a family of models is created:

- EfficientNet-B1 to EfficientNet-B7 scale up the base model by increasing depth, width, and resolution proportionally.

- This systematic scaling approach maintains computational efficiency while improving accuracy.

11.6.3 Why is EfficientNet More Effective

Balanced Scaling Improves Efficiency Unlike previous models that scale depth, width, or resolution separately, EfficientNet scales them together in a way that optimizes accuracy per FLOP.

Comparison with MobileNetV3 EfficientNet builds upon MobileNetV3’s NAS-based design but differs in:

- Optimized Scaling: MobileNetV3 relies on NAS to refine block structures, whereas EfficientNet applies compound scaling to improve overall architecture efficiency.

- Better Accuracy per FLOP: By jointly optimizing all scaling factors, EfficientNet achieves a better tradeoff than MobileNetV3.

- SE Blocks Across the Entire Network: Unlike MobileNetV3, which applies SE blocks selectively, EfficientNet integrates them at all relevant layers.

Comparison with Other Networks

- Compared to ResNets, EfficientNet achieves significantly higher accuracy per parameter.

- Compared to ShuffleNet, EfficientNet provides better optimization for real-world scenarios.

- Compared to MobileNetV2 and V3, EfficientNet systematically improves upon scaling while maintaining efficient building blocks.

11.6.4 Limitations of EfficientNet

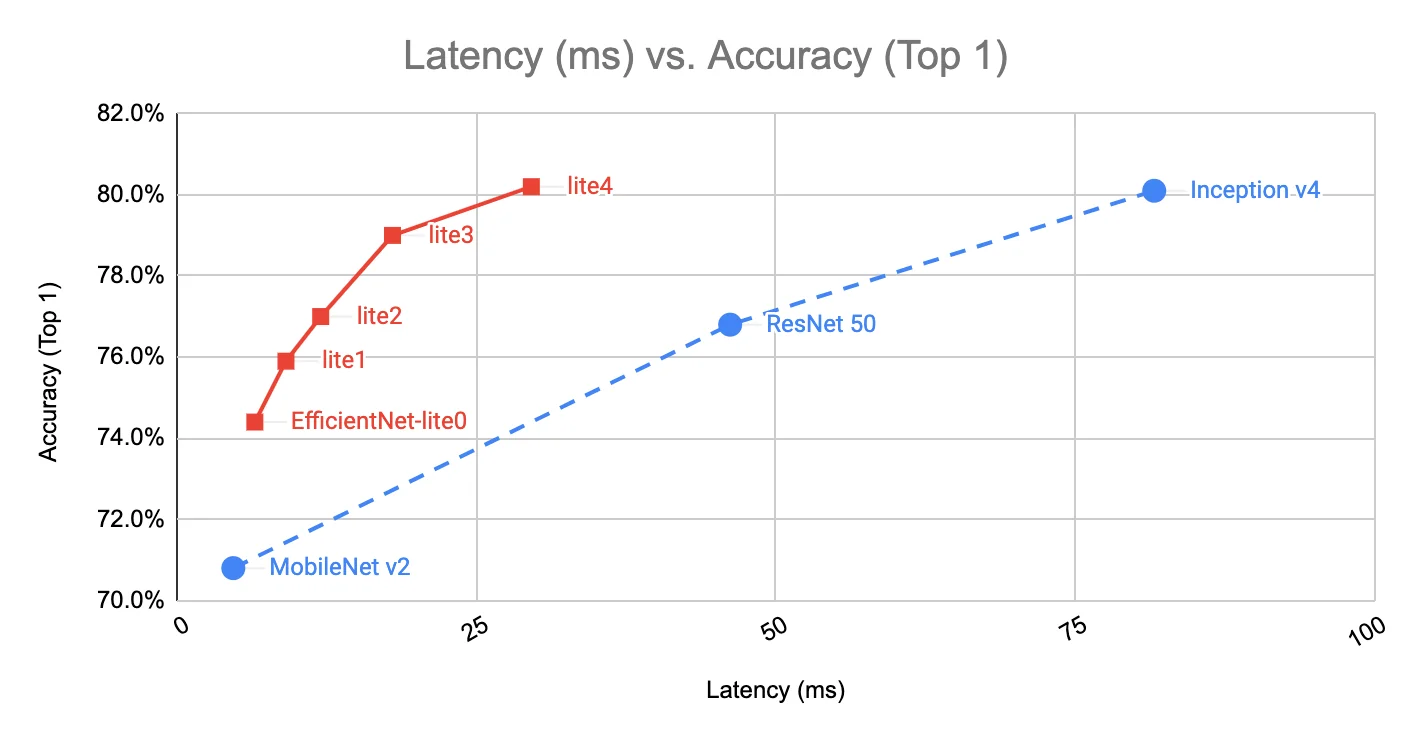

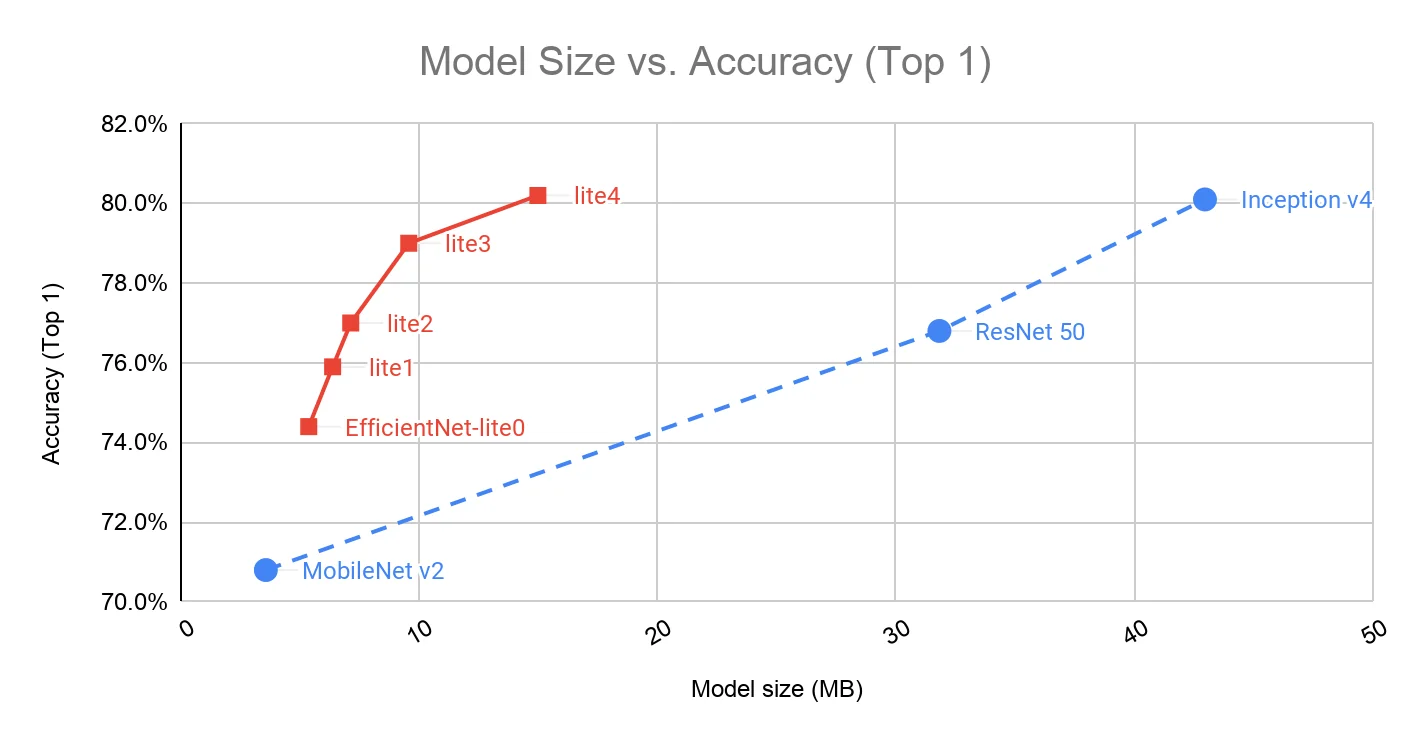

Despite its efficiency in FLOPs, EfficientNet faces a major real-world issue: FLOPs do not directly translate to actual speed. Several factors impact real-world performance:

- Hardware Dependency: Runtime varies significantly across different devices (mobile CPU, server CPU, GPU, TPU).

- Depthwise Convolutions: While efficient on mobile devices, depthwise convolutions become memory-bound on GPUs and TPUs, leading to suboptimal execution times.

- Alternative Convolution Algorithms: Standard FLOP counting does not account for fast convolution implementations (e.g., FFT for large kernels, Winograd for \(3 \times 3\) convolutions), making direct FLOP comparisons misleading.

What’s Next? EfficientNetV2 and Beyond Since EfficientNet’s design focuses on FLOPs rather than actual hardware efficiency, researchers sought ways to improve real-world speed. This led to:

- EfficientNetV2: Improves inference speed and training efficiency.

- NFNets: Removes Batch Normalization for improved training stability (when working with a small mini-batch).

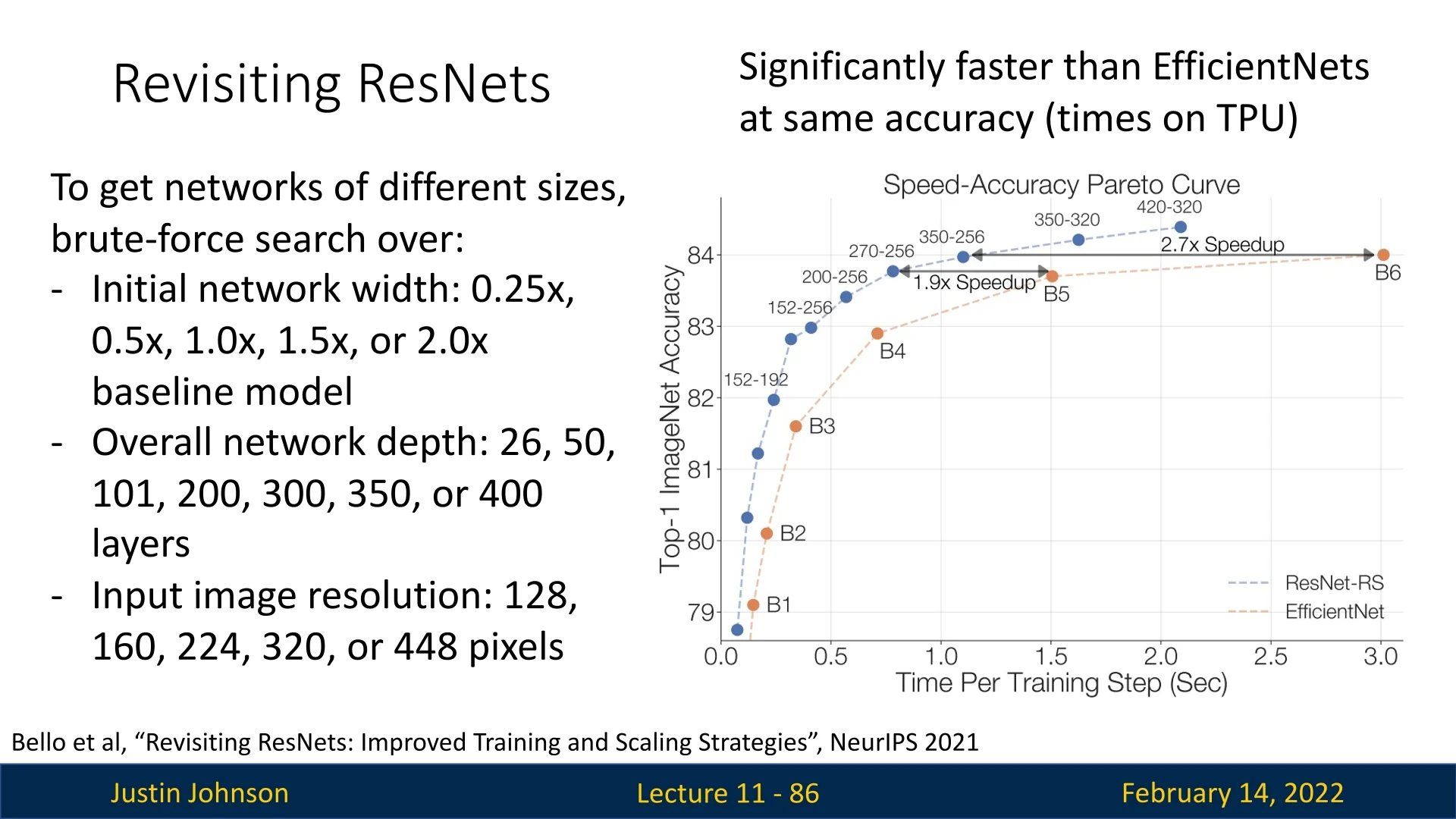

- ResNet-RS: A modernized ResNet with better scaling and training techniques.

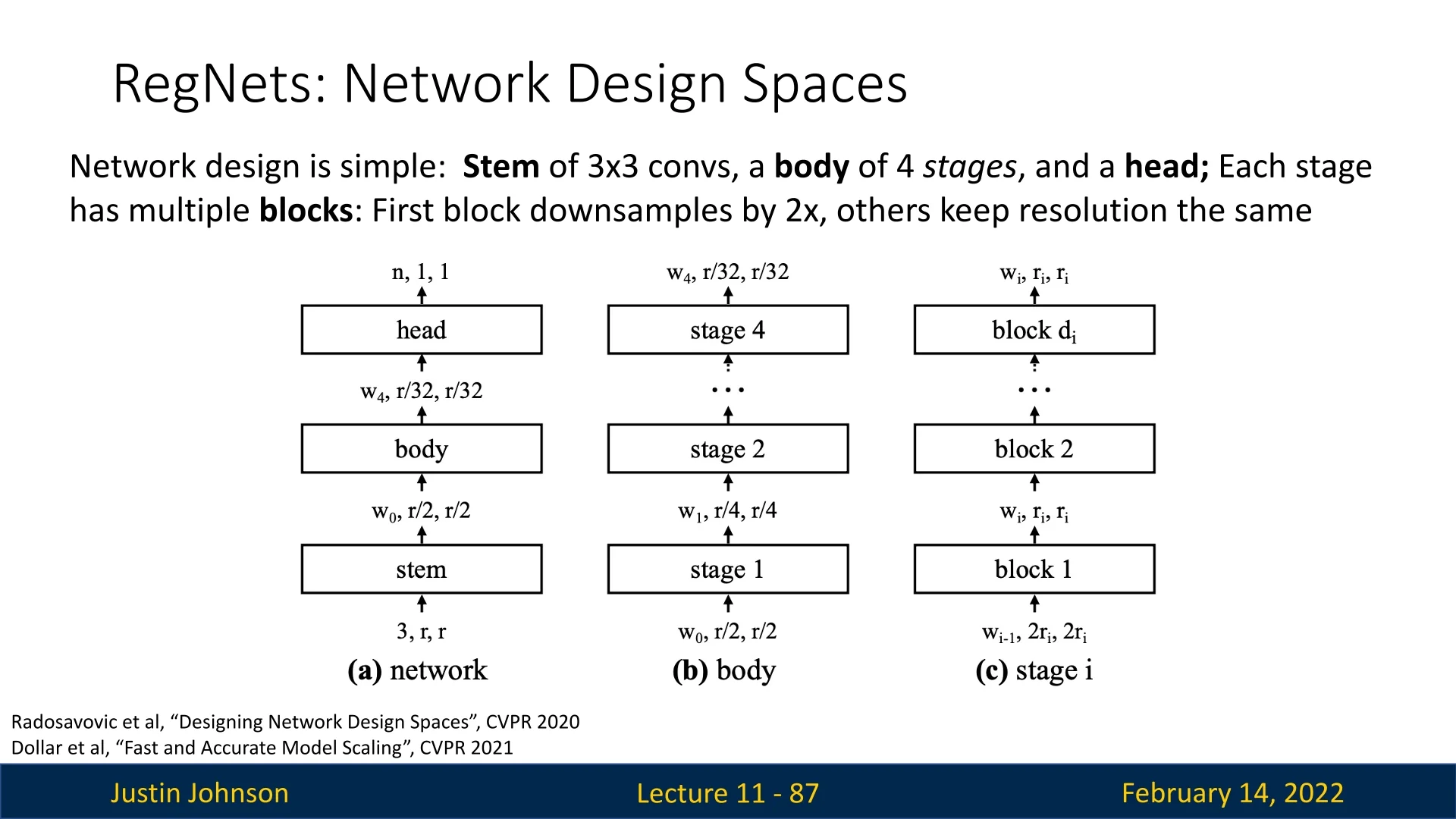

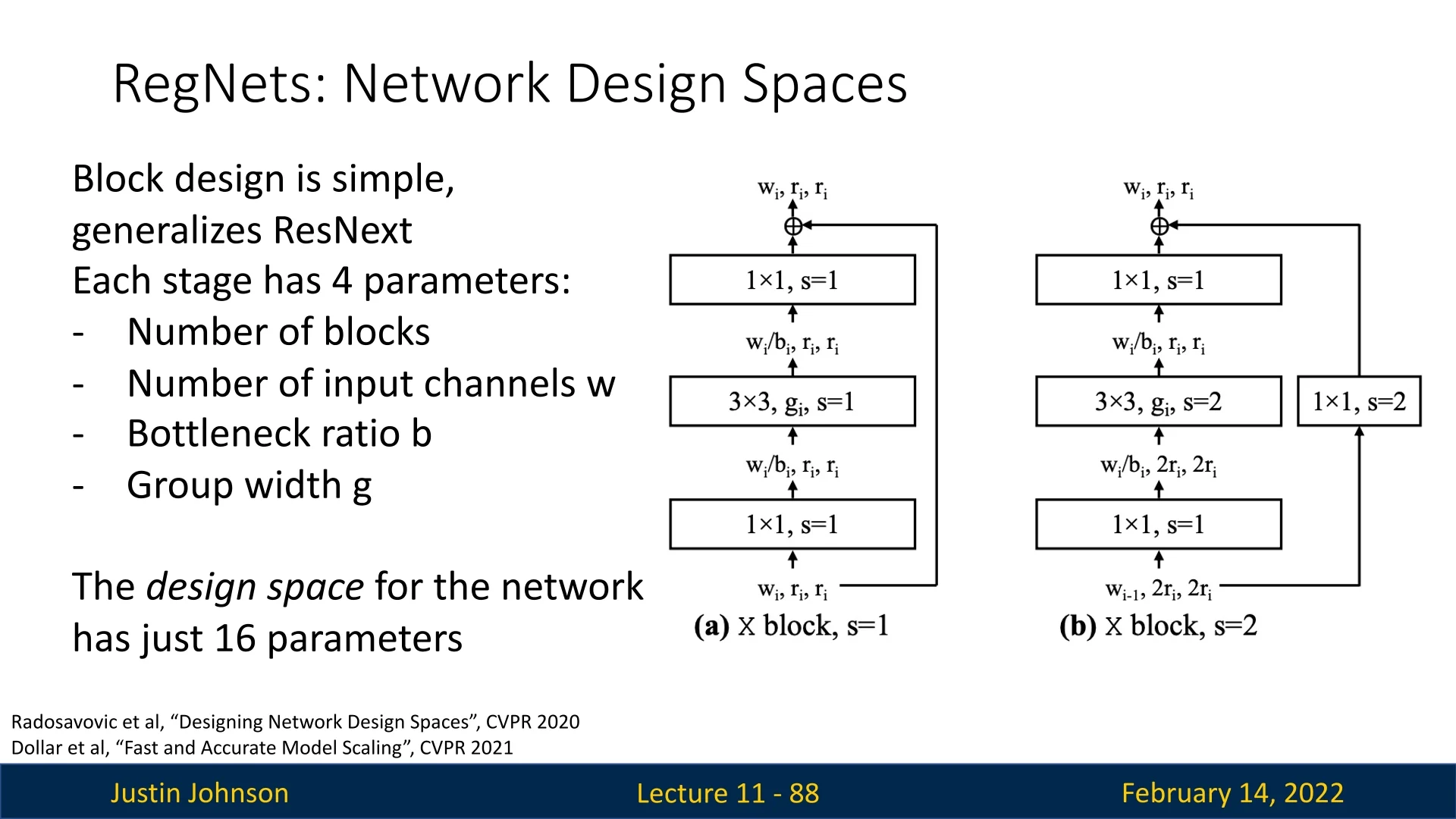

- RegNets: Optimizes the macro architecture rather than just individual block designs.

Conclusion While EfficientNet represents a significant step forward in model scaling, its reliance on depthwise convolutions makes it suboptimal for GPUs and TPUs. Future architectures seek to address these limitations while maintaining high accuracy per FLOP.

Next, we explore EfficientNet-Lite, EfficientNetV2, which build upon EfficientNet’s strengths while improving real-world efficiency.

11.7 EfficientNet-Lite Optimizing EfficientNet for Edge Devices

11.7.1 Motivation for EfficientNet-Lite

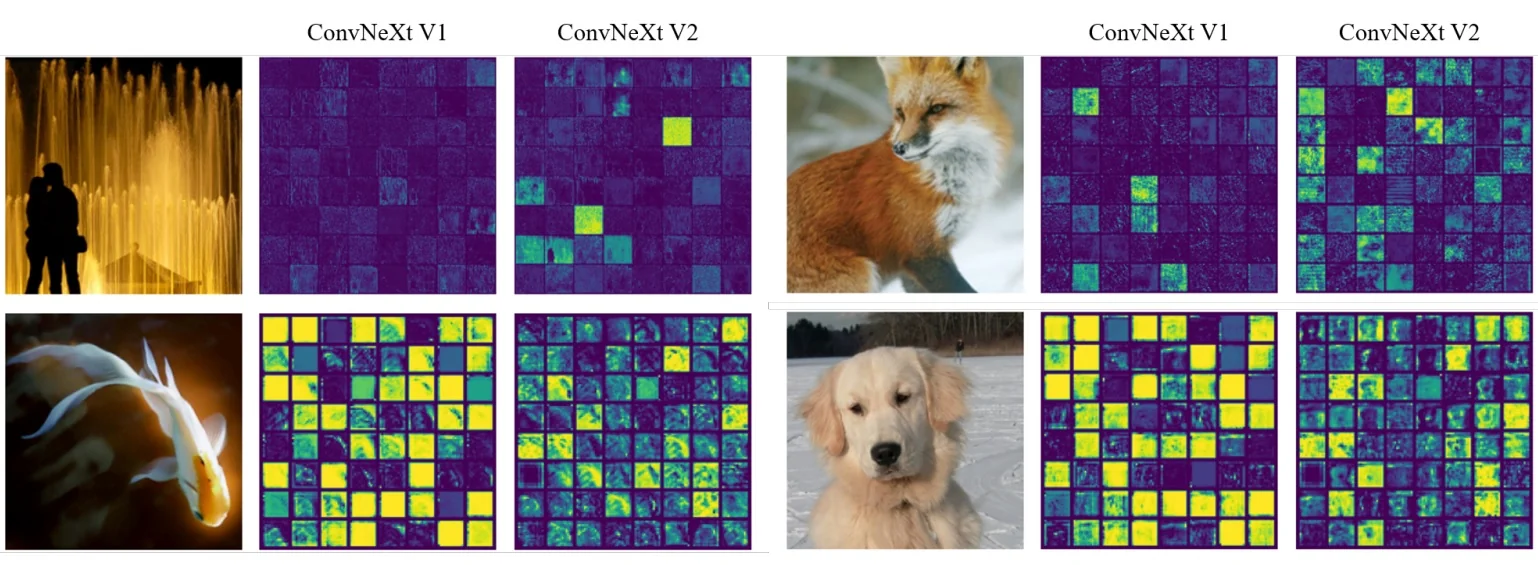

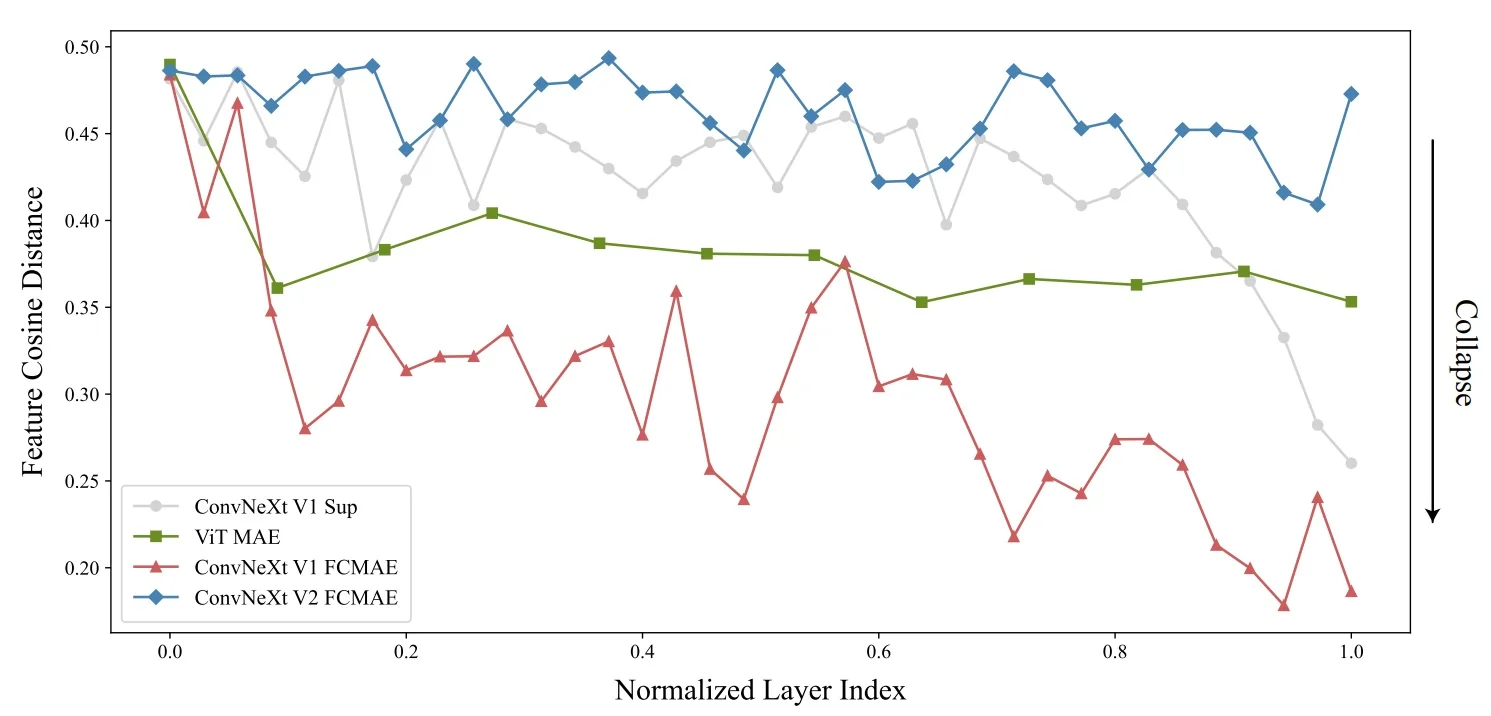

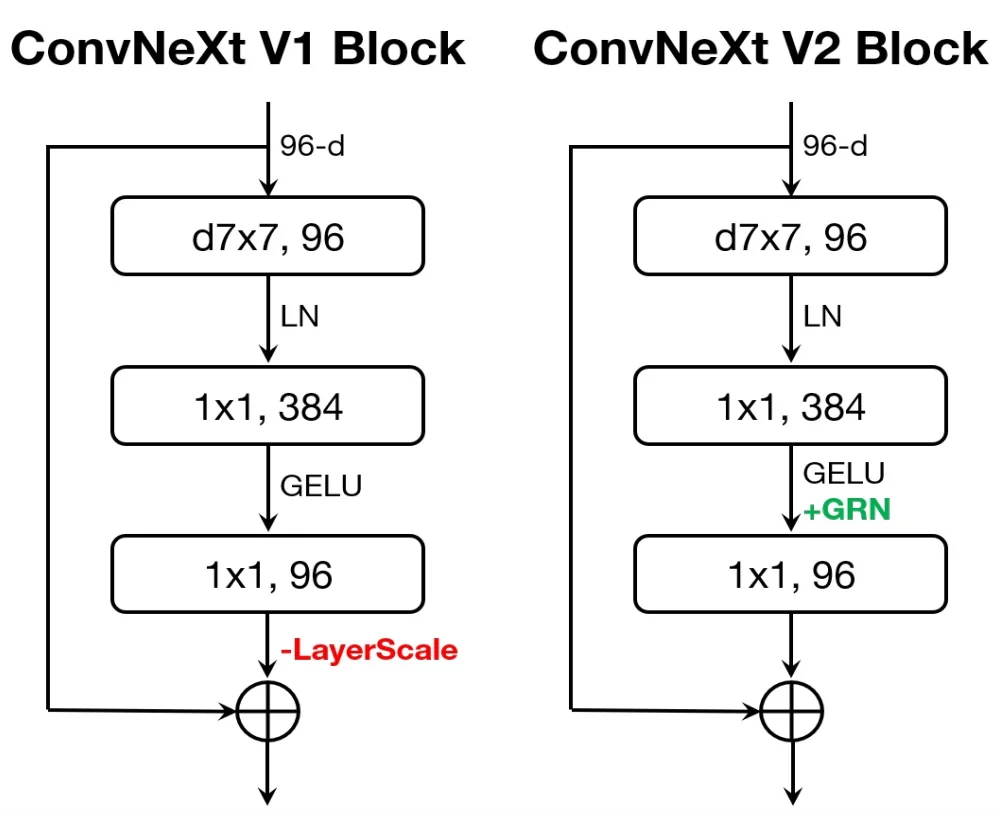

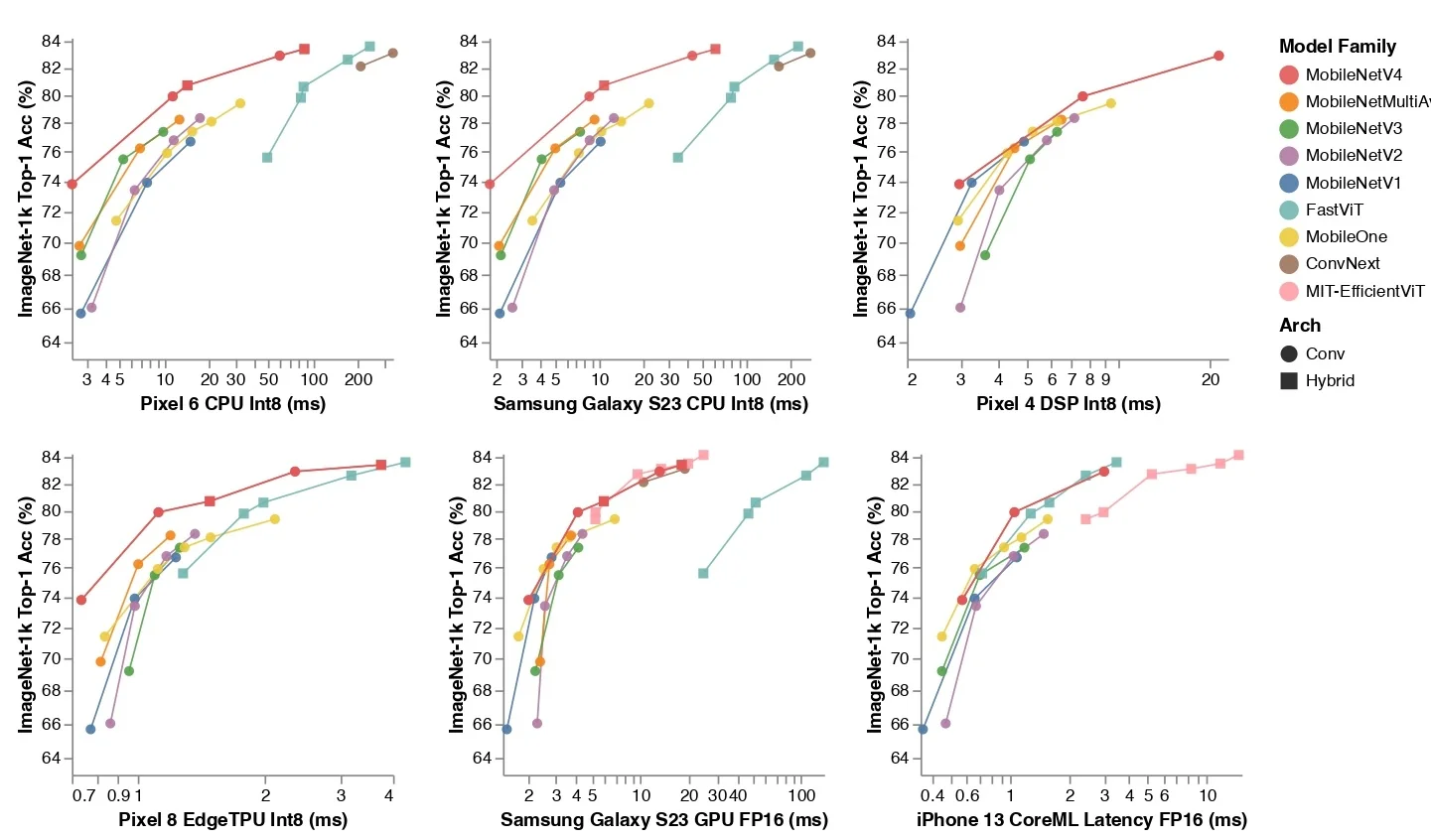

While EfficientNet achieves an excellent balance between accuracy and computational cost, its deployment on edge devices (such as mobile phones and embedded systems) presents challenges. Many hardware accelerators used in mobile and IoT devices have limited support for certain EfficientNet components, leading to inefficiencies in real-world inference.