Lecture 7: Convolutional Networks

7.1 Introduction: The Limitations of Fully-Connected Networks

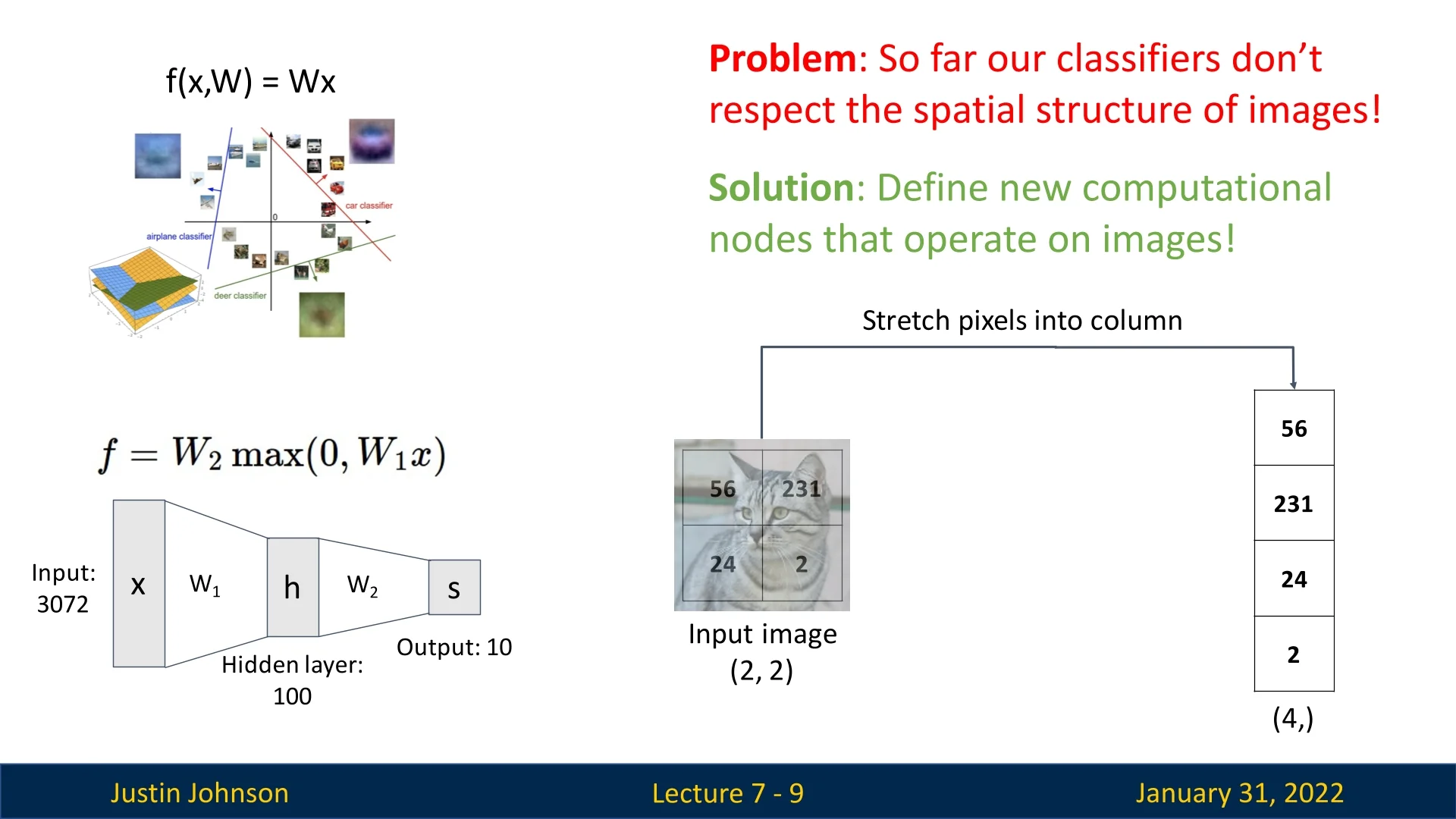

So far, we have explored linear classifiers and fully-connected neural networks. While fully-connected networks are significantly more expressive than simple linear classifiers, they still suffer from a major limitation: they do not preserve the 2D spatial structure of image data.

These models require us to flatten an image into a one-dimensional vector, losing all spatial relationships between pixels. This is problematic for tasks like image classification, where local patterns such as edges and textures are crucial for understanding an image.

To address this issue, Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) introduce new types of layers designed to process images while maintaining their spatial properties.

7.2 Components of Convolutional Neural Networks

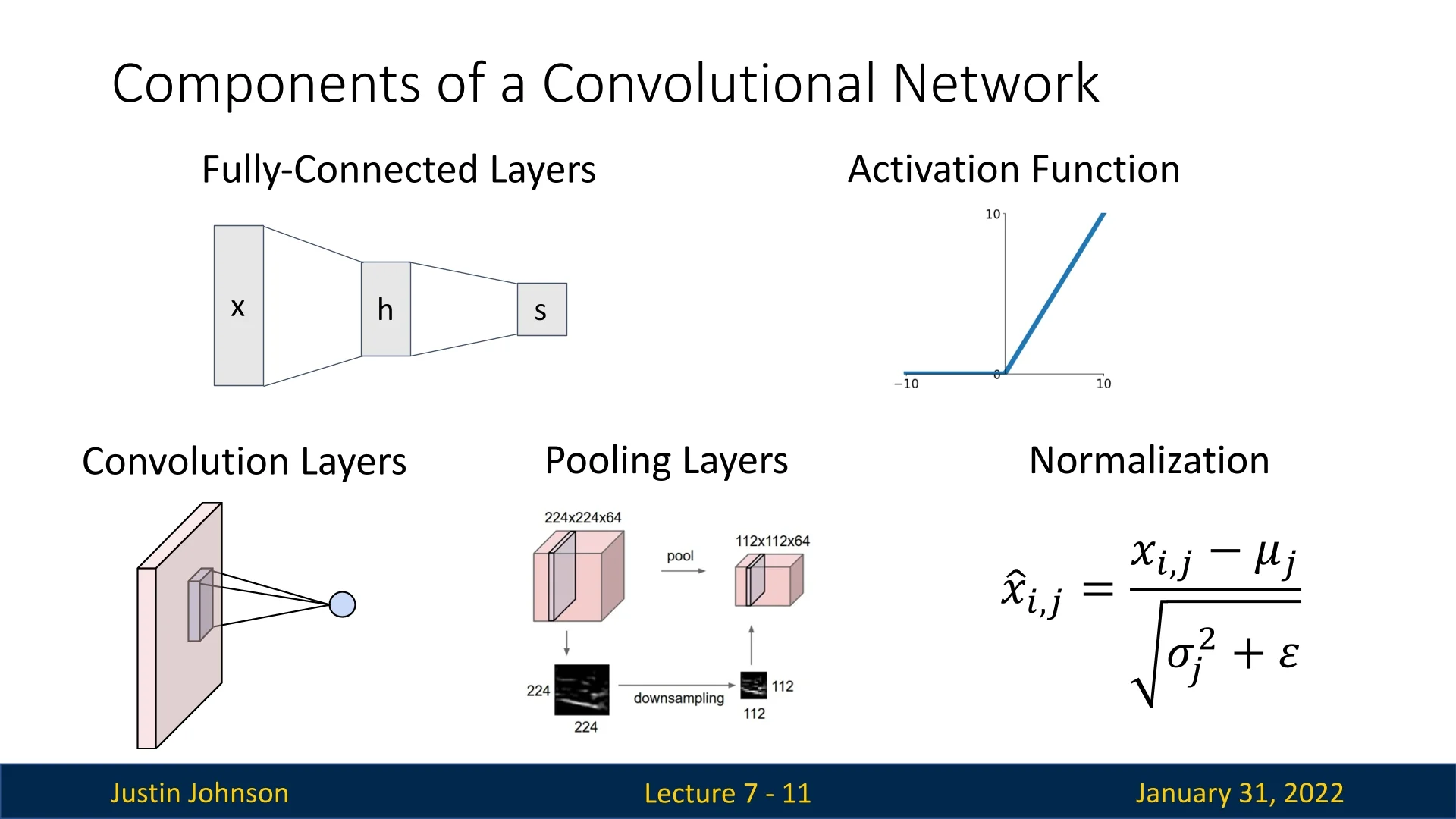

CNNs extend fully-connected networks by introducing the following specialized layers:

- 1.

- Convolutional Layers: Preserve spatial structure and detect patterns using filters (kernels) that slide across the image.

- 2.

- Pooling Layers: Reduce spatial dimensions while retaining essential features.

- 3.

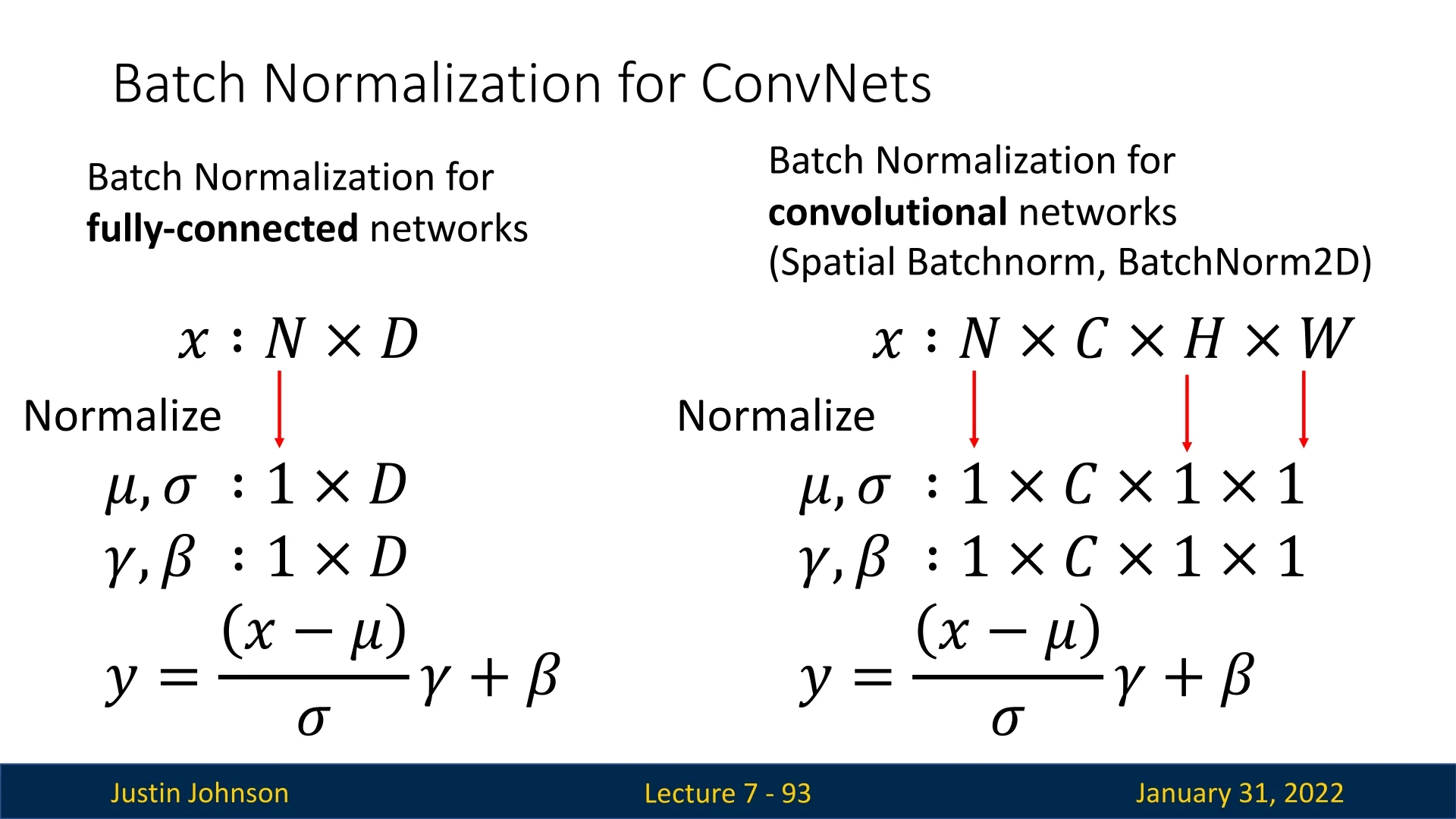

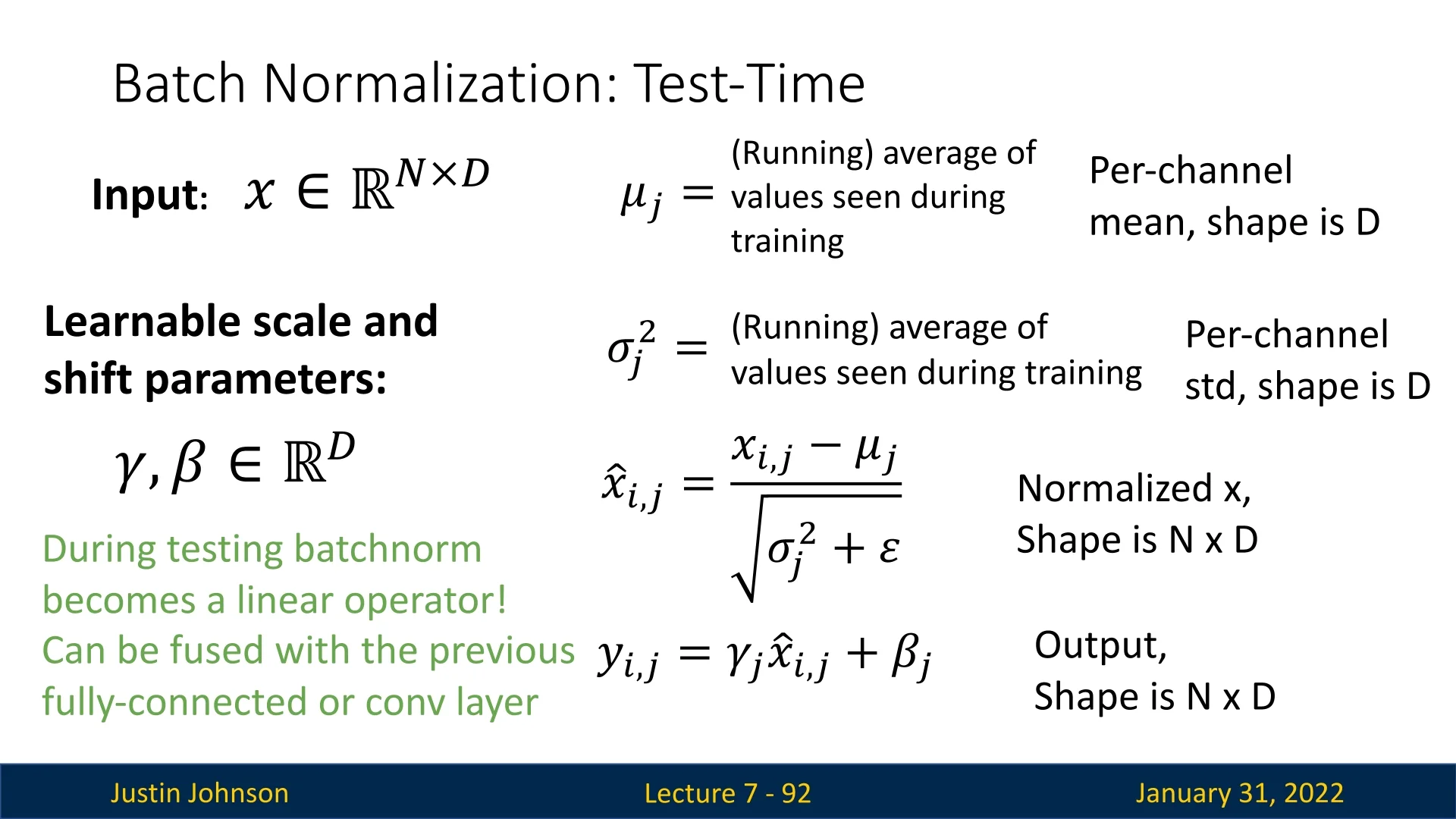

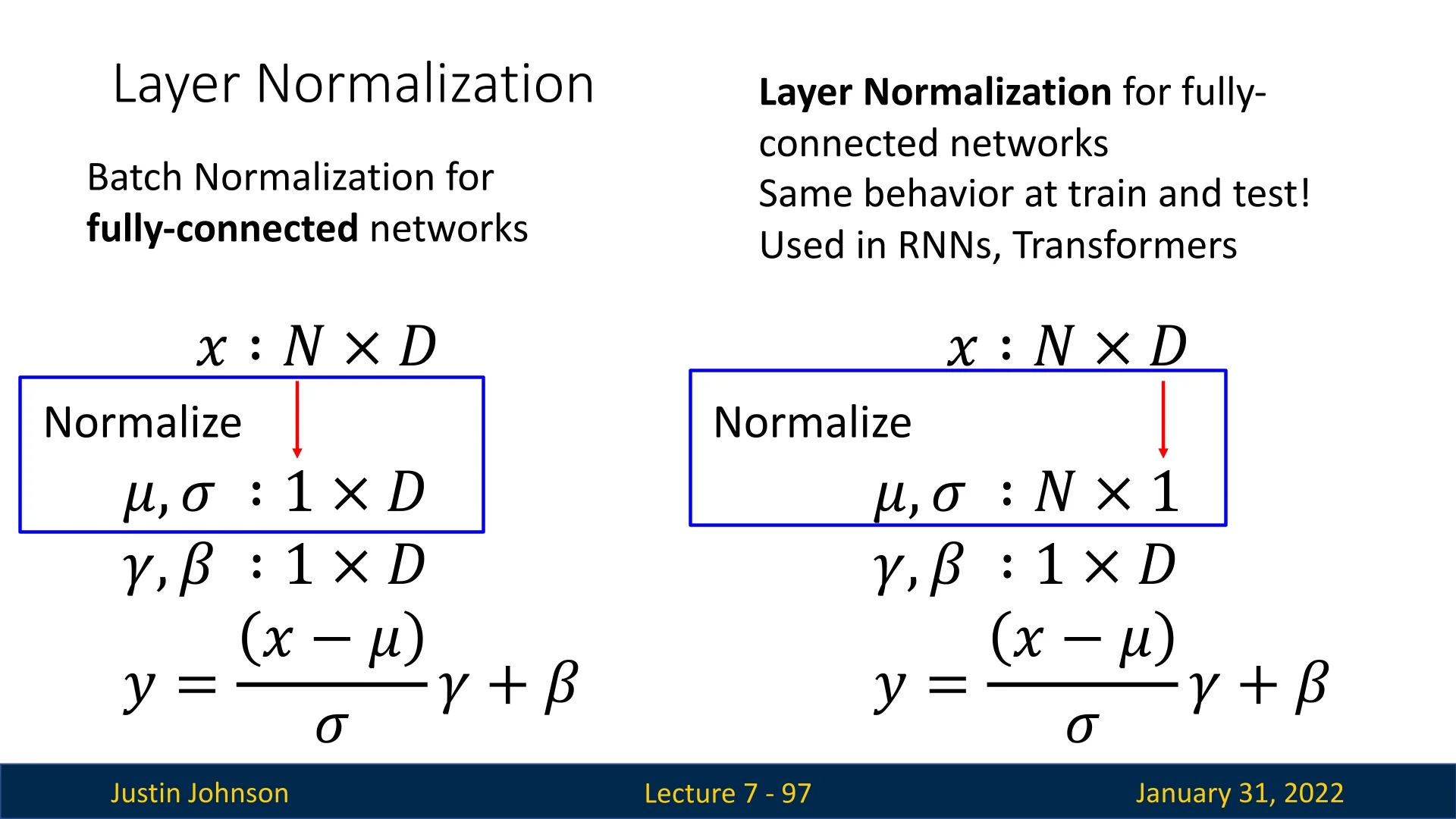

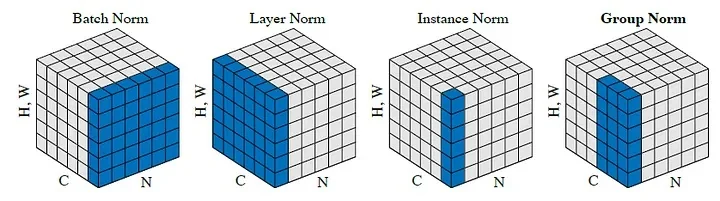

- Normalization Layers (e.g., Batch Normalization): Stabilize training and improve performance.

These layers allow CNNs to effectively capture hierarchical features from images, making them highly effective for computer vision tasks.

7.3 Convolutional Layers: Preserving Spatial Structure

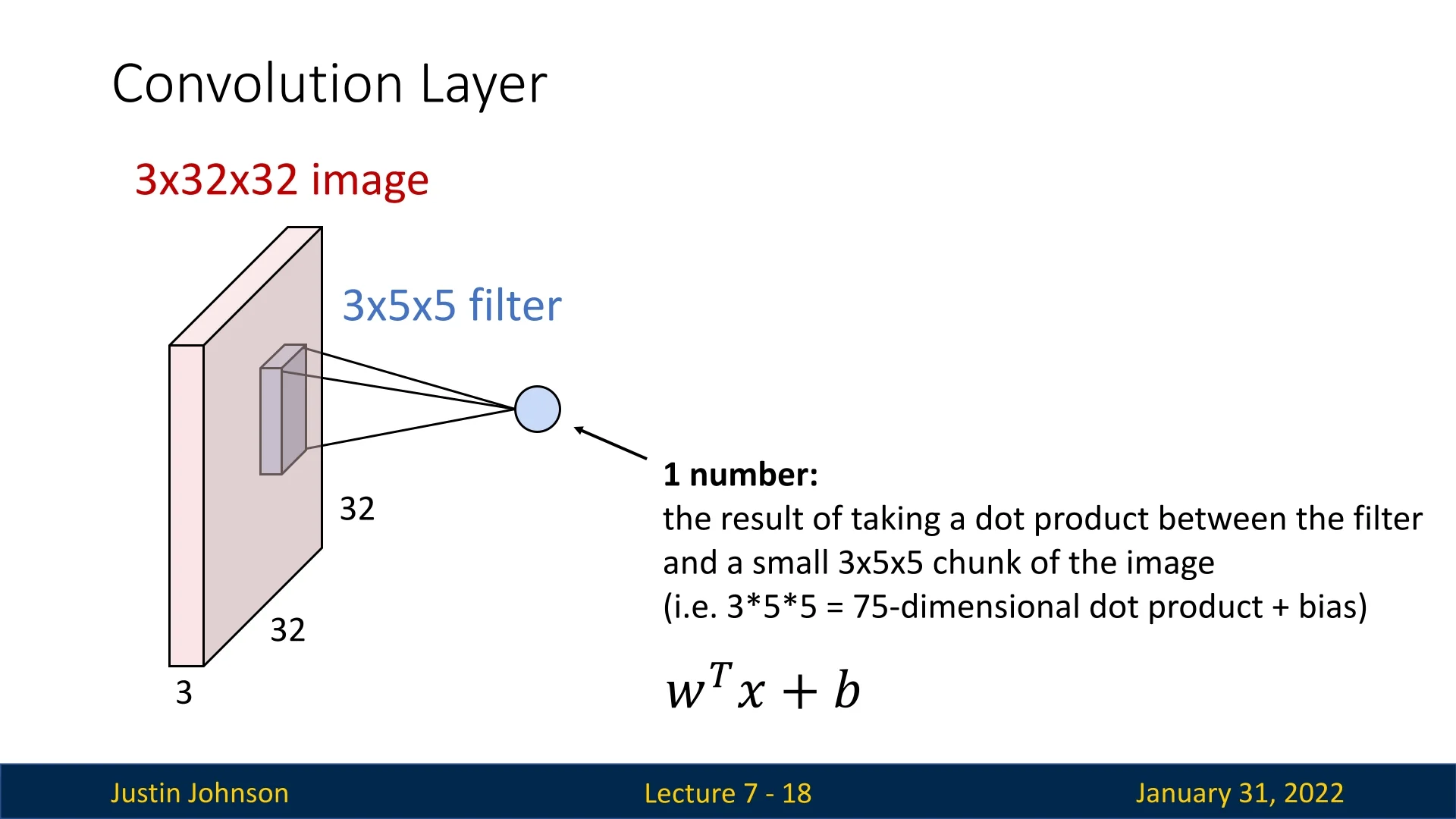

A convolutional layer is designed to process images while maintaining their 2D structure. Instead of flattening the image into a single vector, convolutional layers operate on small local patches of the input, capturing spatially localized patterns such as edges, corners, and textures.

7.3.1 Input and Output Dimensions

A convolutional layer processes an input tensor while preserving its spatial structure. Unlike fully connected layers, which flatten the input into a vector, convolutional layers operate directly on structured data, maintaining spatial relationships between pixels.

The input to a convolutional layer typically has the shape: \[ C_{\mbox{in}} \times H \times W \] where:

- \(C_{\mbox{in}}\) is the number of input channels (e.g., 3 for an RGB image, where each channel corresponds to red, green, or blue intensity),

- \(H\) and \(W\) represent the height and width of the input image or feature map (a 2D representation of extracted features).

The layer applies a set of filters (also called kernels), where each filter has the shape: \[ C_{\mbox{in}} \times K_h \times K_w. \] Here:

- \(K_h\) and \(K_w\) define the spatial size (height and width) of the filter,

- Each filter always spans all \(C_{\mbox{in}}\) input channels, meaning it processes all color or feature layers together.

Common Filter Sizes Typically, \(K_h\) and \(K_w\) are small, such as 3, 5, or 7, to detect fine-grained patterns while maintaining computational efficiency. Most convolutional layers use square filters (\(K_h = K_w\)), though some architectures employ non-square kernels for specialized feature extraction. For example, Google’s Inception architecture, which we will explore later, uses asymmetric convolutions such as \(1 \times 3\) and \(3 \times 1\) to improve computational efficiency while maintaining expressive power.

Why Are Kernel Sizes Typically Odd? While convolution kernels can have even or odd dimensions, odd-sized kernels (\(3 \times 3\), \(5 \times 5\)) are commonly used due to their advantages in preserving spatial structure and ensuring consistent feature extraction.

- Preserving Spatial Alignment: Odd-sized kernels naturally align with a central pixel, ensuring that the output remains centered relative to the input. This prevents unintended shifts in feature maps, which could cause misalignment across layers and disrupt learning.

- Consistent Neighboring Context: When stacking multiple convolutional layers, each output pixel is influenced symmetrically by its surrounding pixels. This balanced context stabilizes feature learning and helps capture hierarchical patterns effectively.

Even-sized kernels (e.g., \(2 \times 2\), \(4 \times 4\)) do not have a single center pixel, requiring additional adjustments when aligning the filter to the input, and are hence not common.

7.3.2 Filter Application and Output Calculation

Each filter slides (convolves) over the spatial dimensions of the image, computing a dot product between its weights and the corresponding patch of the input at each position. The sum of these dot products, plus a bias term, produces the activation for that position.

Mathematically, for a given position \((i, j)\), the convolution operation computes: \[ y_{i,j} = \sum _{c=1}^{C_{\mbox{in}}} \sum _{m=1}^{K_h} \sum _{n=1}^{K_w} W_{c,m,n} \cdot X_{c, i+m, j+n} + b \] where:

- \( W_{c,m,n} \) represents the filter weights.

- \( X_{c, i+m, j+n} \) represents the corresponding region of the input image.

- \( b \) is the bias term.

Each filter produces a single activation map, and stacking multiple filters results in a 3D output tensor.

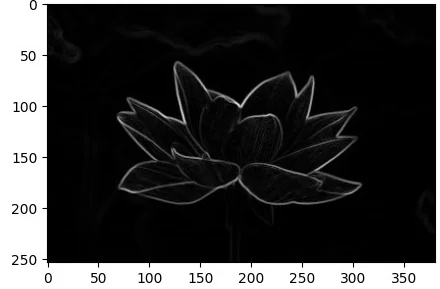

Enrichment 7.3.3: Understanding Convolution Through the Sobel Operator

To build intuition for convolutional operations, we start with a simple example: applying a \(3 \times 3\) 2D filter to a single-channel (\(C_{\mbox{in}} = 1\)) grayscale image. Later we’ll dive into more practical examples, to better understand how convolutional layers work. More specifically, we’ll cover how such layers work with several multi-channel filters applied to the input image, integrated along with their corresponding biases, along with other mechanisms like strides/padding (larger than 1), that are often seen in conv-nets.

Enrichment 7.3.3.1: Using the Sobel Kernel for Edge Detection

A widely used filter for detecting edges in images is the Sobel operator, which approximates the image gradient along the horizontal and vertical directions. This filter is based on the concept of central differences, a discrete method for estimating gradients in a sampled function—such as an image.

Approximating Image Gradients with the Sobel Operator To estimate the gradient at each pixel, we can use a basic finite difference approach. The simplest method is the forward difference, which approximates the derivative at a given pixel by computing the difference between its right neighbor and itself. However, this method introduces a shift in the computed gradient locations. A more accurate approach is the central difference, which averages the difference between the left and right neighbors:

\[ \frac {\partial I}{\partial x} \approx \frac {I(x+1, y) - I(x-1, y)}{2}. \]

Similarly, for the vertical gradient:

\[ \frac {\partial I}{\partial y} \approx \frac {I(x, y+1) - I(x, y-1)}{2}. \]

These central difference approximations form the basis of the gradient operators used in edge detection.

Basic Difference Operators A simple discrete implementation of the central difference method would use the following filters:

\[ \mbox{Diff}_x = \begin {bmatrix} -1 & 0 & 1 \\ -1 & 0 & 1 \\ -1 & 0 & 1 \end {bmatrix}, \quad \mbox{Diff}_y = \begin {bmatrix} -1 & -1 & -1 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 1 & 1 & 1 \end {bmatrix}. \]

These filters compute intensity differences between neighboring pixels along the horizontal and vertical axes, highlighting abrupt changes. However, they treat all pixels equally, making them highly sensitive to noise. A small random fluctuation in intensity could result in large, unstable gradient estimates.

The Sobel Filters: Adding Robustness The Sobel filters improve upon these simple difference operators by incorporating a Gaussian-like weighting to give more importance to the central pixels:

\[ \mbox{Sobel}_x = \begin {bmatrix} 1 \\ 2 \\ 1 \end {bmatrix} \begin {bmatrix} 1 & 0 & -1 \end {bmatrix} = \begin {bmatrix} 1 & 0 & -1 \\ 2 & 0 & -2 \\ 1 & 0 & -1 \end {bmatrix} \]

\[ \mbox{Sobel}_y = \begin {bmatrix} 1 \\ 0 \\ -1 \end {bmatrix} \begin {bmatrix} 1 & 2 & 1 \end {bmatrix} = \begin {bmatrix} 1 & 2 & 1 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 \\ -1 & -2 & -1 \end {bmatrix} \]

Enrichment 7.3.3.2: Why Does the Sobel Filter Use These Weights?

- Improving Gradient Accuracy: The \([-1, 0, 1]\) pattern in \(\mbox{Sobel}_x\) is a discrete approximation of the central difference derivative, meaning it captures intensity changes along the horizontal axis, responding to vertical edges. Similarly, \(\mbox{Sobel}_y\) captures intensity changes along the vertical axis, detecting horizontal edges.

- Smoothing High-Frequency Noise: The \([1, 2, 1]\) weighting acts as a mild low-pass filter, averaging nearby pixels to reduce noise sensitivity while maintaining edge sharpness.

- Preserving Image Structure: The use of a larger weight at the center (\(2\)) ensures that local gradient computations are less affected by isolated pixel noise and instead capture broader edge structures.

Enrichment 7.3.3.3: Computing the Gradient Magnitude

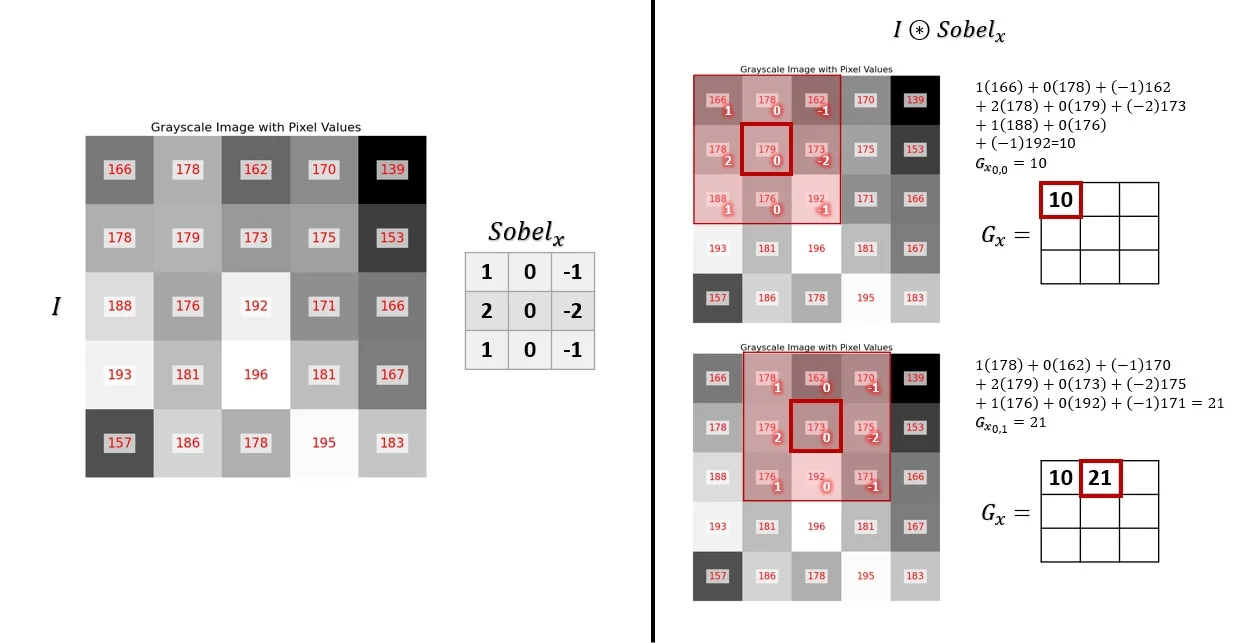

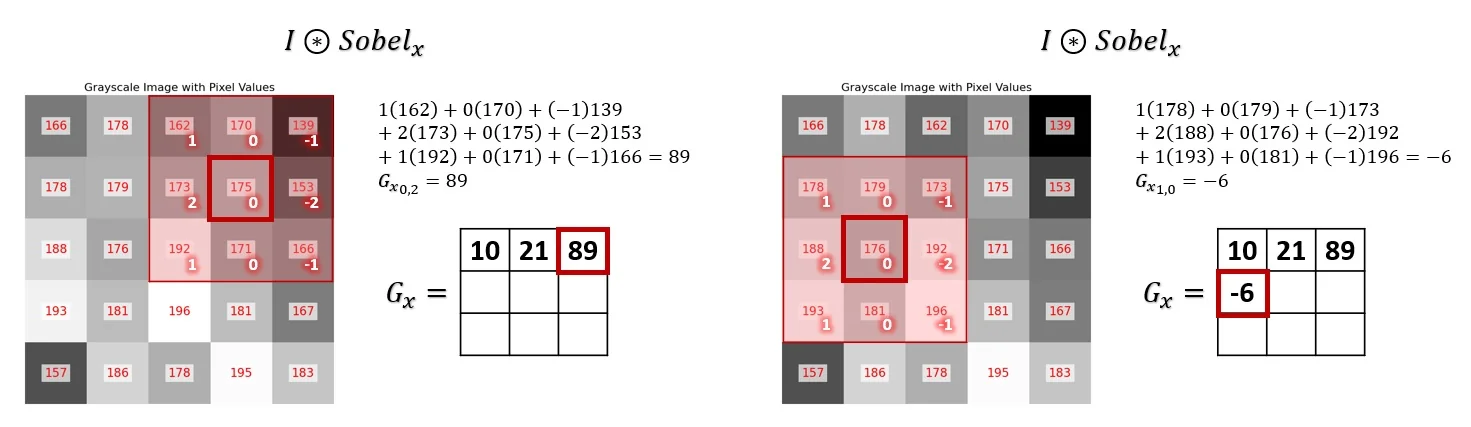

At each spatial location in the image, the kernel is positioned over a \(3 \times 3\) region of pixel intensities. The convolution operation computes the dot product between the kernel and the underlying pixel values, yielding a new intensity that reflects the local gradient in the selected direction.

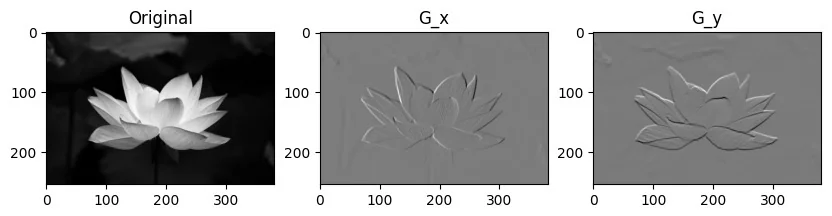

Applying \(\mbox{Sobel}_x\) results in an edge map \(G_x=I * \mbox{Sobel}_x\), where larger absolute values indicate strong vertical edges (intensity changes along the horizontal direction). Similarly, applying \(\mbox{Sobel}_y\) results in an edge map \(G_y=I * \mbox{Sobel}_y\), where larger absolute values indicate strong horizontal edges (intensity changes along the vertical direction).

To combine both directions, we compute the gradient magnitude:

\[ G = \sqrt {G_x ^2 + G_y ^2}. \]

To better understand the effect of convolution with the Sobel filter, consider an example grayscale image where distinct edges are present. As the kernel slides over the image:

- Areas with constant intensity produce near-zero outputs (low gradient).

- Regions with sudden changes in intensity (edges) produce large values, indicating strong gradients.

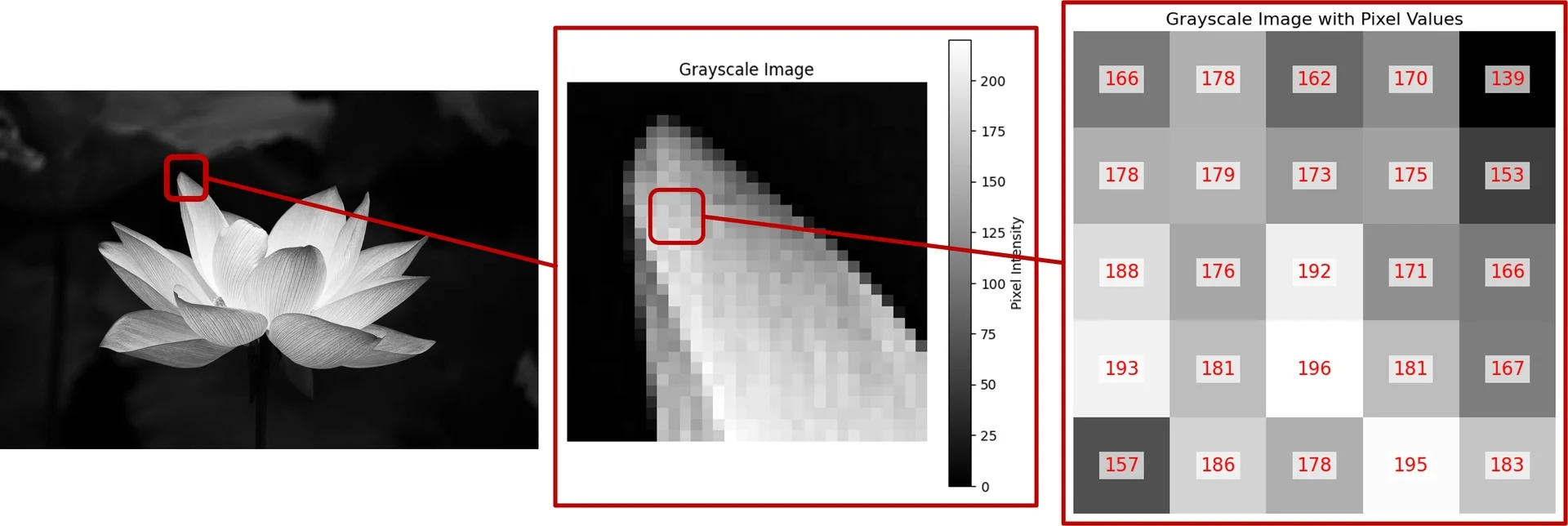

We will proceed to visualize this process, taking the cropped zoom-in part of the original image as seen in Figure 7.5. We’ll first examine the computation using a single filter channel \(\mbox{Sobel}_x\), convolved with the cropped patch.

At the end of this process, we obtain an output in the form of a 2D edge map, \(G_x\), where larger absolute values correspond to pixels that are likely part of a vertical edge (corresponding to large gradients along the horizontal axis of the image). The same process can be done with the other single-filter channel \(\mbox{Sobel}_y\), resulting in \(G_y\), where larger absolute values correspond to horizontal edges.

We can apply this process to the entire image, obtaining the full edge maps \(G_x\) and \(G_y\). By combining them, we get a single edge image:

\[ G = \sqrt {G_x ^2 + G_y ^2}. \]

Convolutional layers in neural networks use this operation to extract meaningful features, such as edges and textures, which serve as the foundation for deeper representations. While neural networks learn their own filters during training, edge-detecting filters like Sobel demonstrate how convolution naturally captures important structural information.

Hands-On Exploration To build deeper intuition around convolutions, it can be enlightening to interactively apply various kernels to images. One accessible resource is Setosa’s Image Kernels Demo, where you can hover over a grayscale image and experiment with different filters like the Sobel filter on the fly. Tinkering in this way helps illustrate how individual convolutional kernels isolate specific visual features and produce characteristic activation patterns.

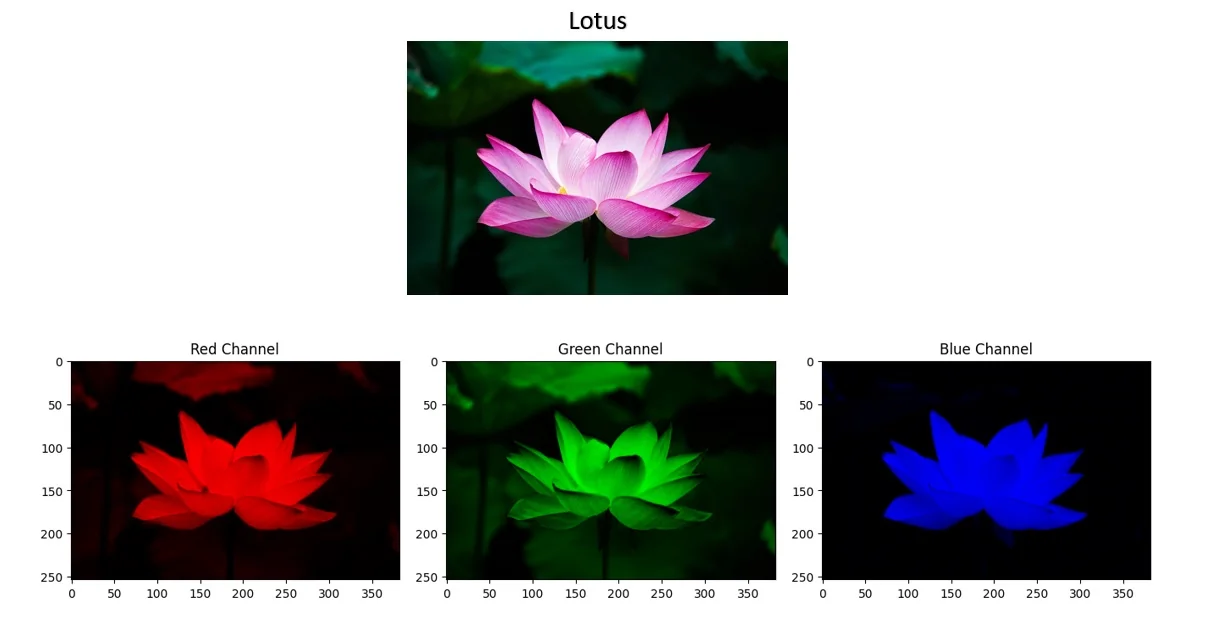

Enrichment 7.4: Convolutional Layers with Multi-Channel Filters

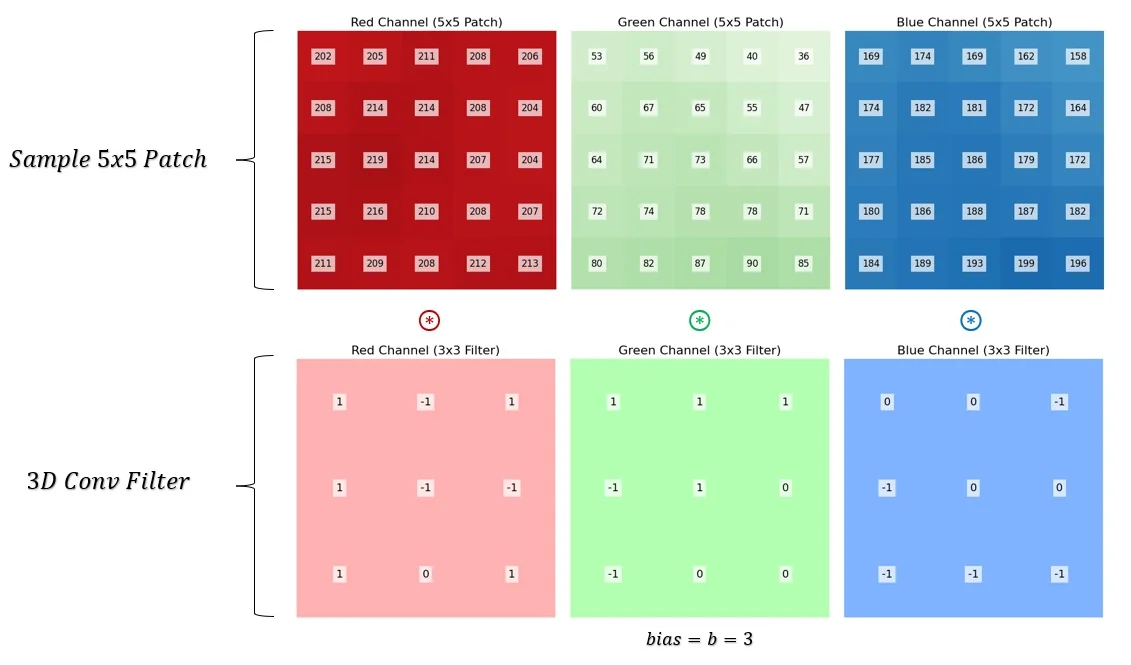

Previously, in 7.3.2, we explored how convolution operates using a single \(3 \times 3\) 2D filter. Now, we extend this concept to multi-channel inputs, such as RGB images, which contain multiple color channels. Convolutional layers typically consist of multiple multi-dimensional filters, each spanning all input channels. Additionally, each filter has an associated bias term in the bias vector \(\mathbf {b}\), which is added to the convolution result to introduce additional flexibility.

To illustrate this extension, we consider an RGB image of a Lotus flower. Unlike grayscale images, which contain a single intensity channel, RGB images have three channels—red, green, and blue—each containing spatial information about the corresponding color component.

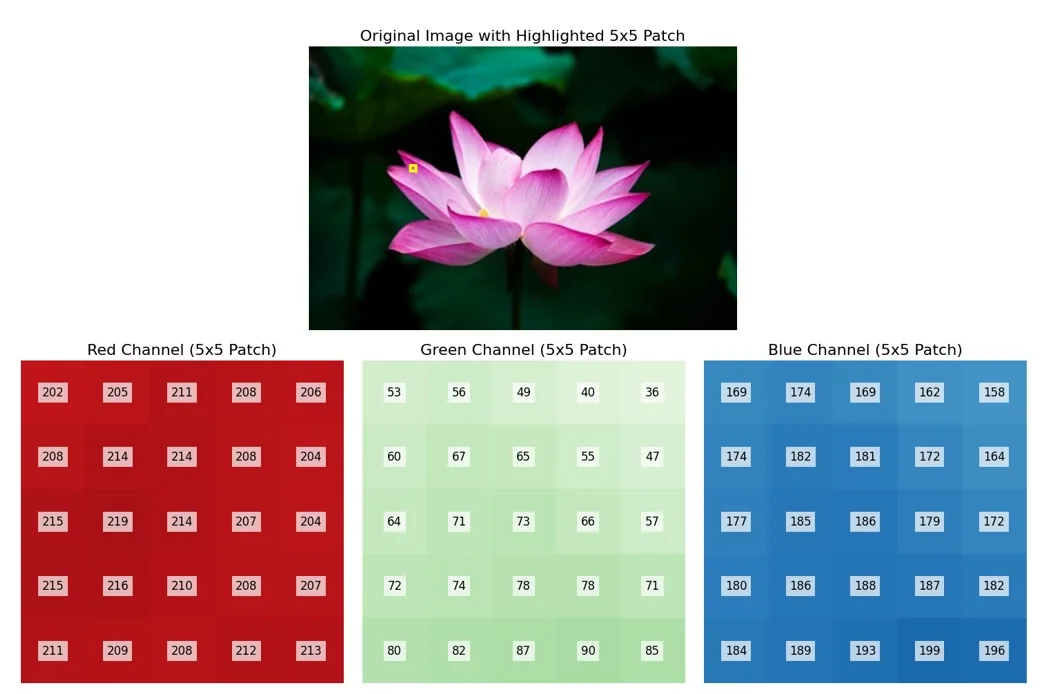

Enrichment 7.4.1: Extending Convolution to Multi-Channel Inputs

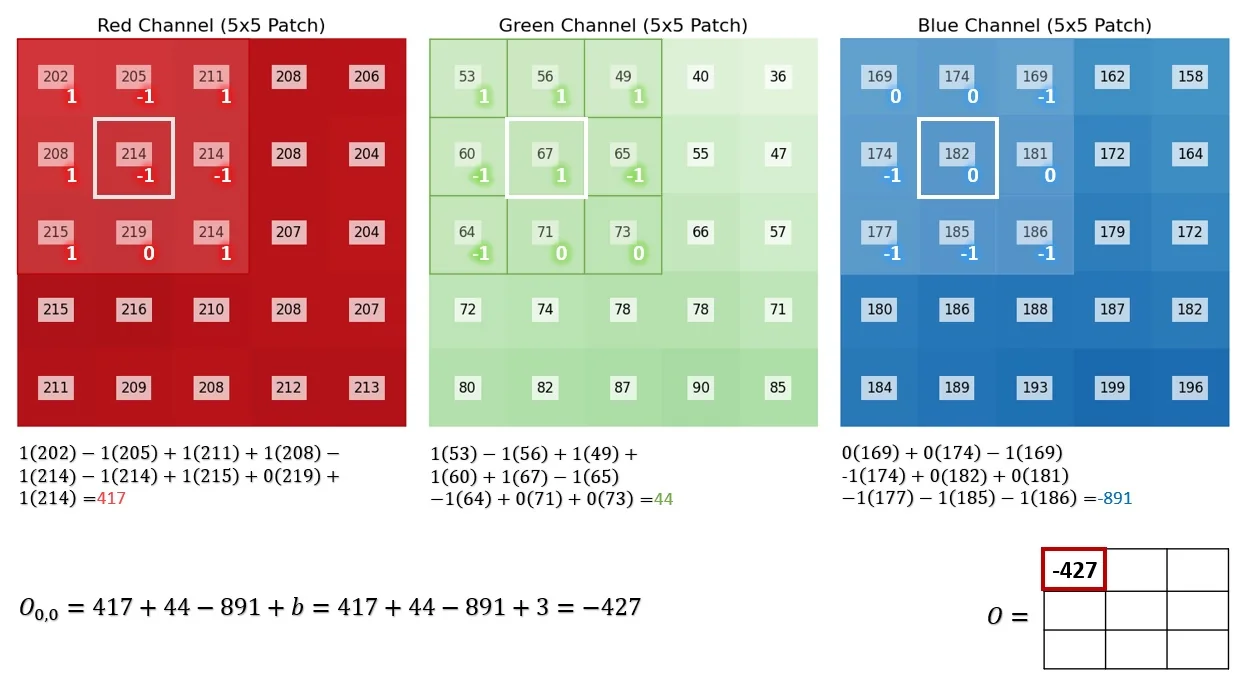

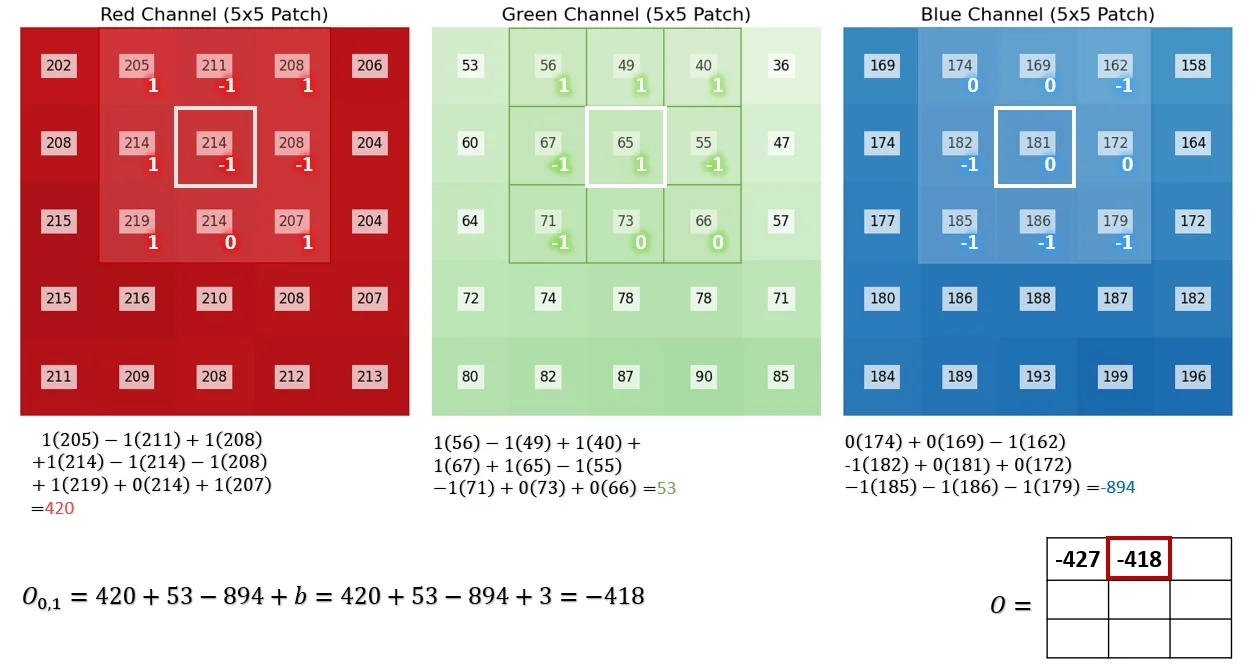

To demonstrate multi-channel convolution, consider a randomly selected \(5 \times 5\) patch from the image along with a single randomly initialized \(3\)-channel filter.

Multi-Channel Convolution Process When performing convolution on multi-channel images, each filter is applied separately to each channel, and the results are summed to produce a single output value for each spatial position. This is equivalent to computing multiple 2D convolutions (one per input channel) and then aggregating the results.

- Each channel of the filter is convolved with its corresponding channel in the input patch.

- The outputs from all channels are summed together at each spatial location.

- A bias term associated with the filter is added to the summed result.

Sliding the Filter Across the Image

After computing the first output pixel, the filter slides spatially to the next position, repeating the same process across the entire image.

From Single Filters to Complete Convolutional Layers A full convolutional layer consists of multiple filters, each producing a separate activation map. The number of filters, \( C_{\mbox{out}} \), determines the number of output channels in the resulting feature map: \[ C_{\mbox{out}} \times H' \times W'. \] Each filter detects different spatial patterns, allowing the network to capture diverse features such as edges, textures, or object parts. By stacking multiple layers, we progressively build hierarchical representations of the input.

What Our Example Missed: Padding and Stride Our example demonstrated how a convolutional filter processes an image patch, but real-world applications introduce additional complexities:

- Incomplete Coverage of the Image: We only applied convolution to a limited region. In practice, the filter moves across the entire image, computing feature responses at each location.

- Handling Image Borders – Padding: Convolution reduces spatial dimensions unless padding is added around the image. Padding ensures that feature extraction extends to edge pixels and helps control output size.

- Stride – Controlling Spatial Resolution: We assumed a step size of 1 when sliding the filter. Using a larger step size (stride) allows for downsampling, reducing spatial dimensions while preserving depth, helping in mitigation of computational cost.

Are Kernel Values Restricted? Unlike fixed edge detection filters (e.g., Sobel), the values in convolutional kernels are not predefined—they are learned during training. Filters evolve to capture useful features depending on the task. While no strict range constraints exist, regularization techniques such as weight decay help prevent extreme values, improving stability and generalization.

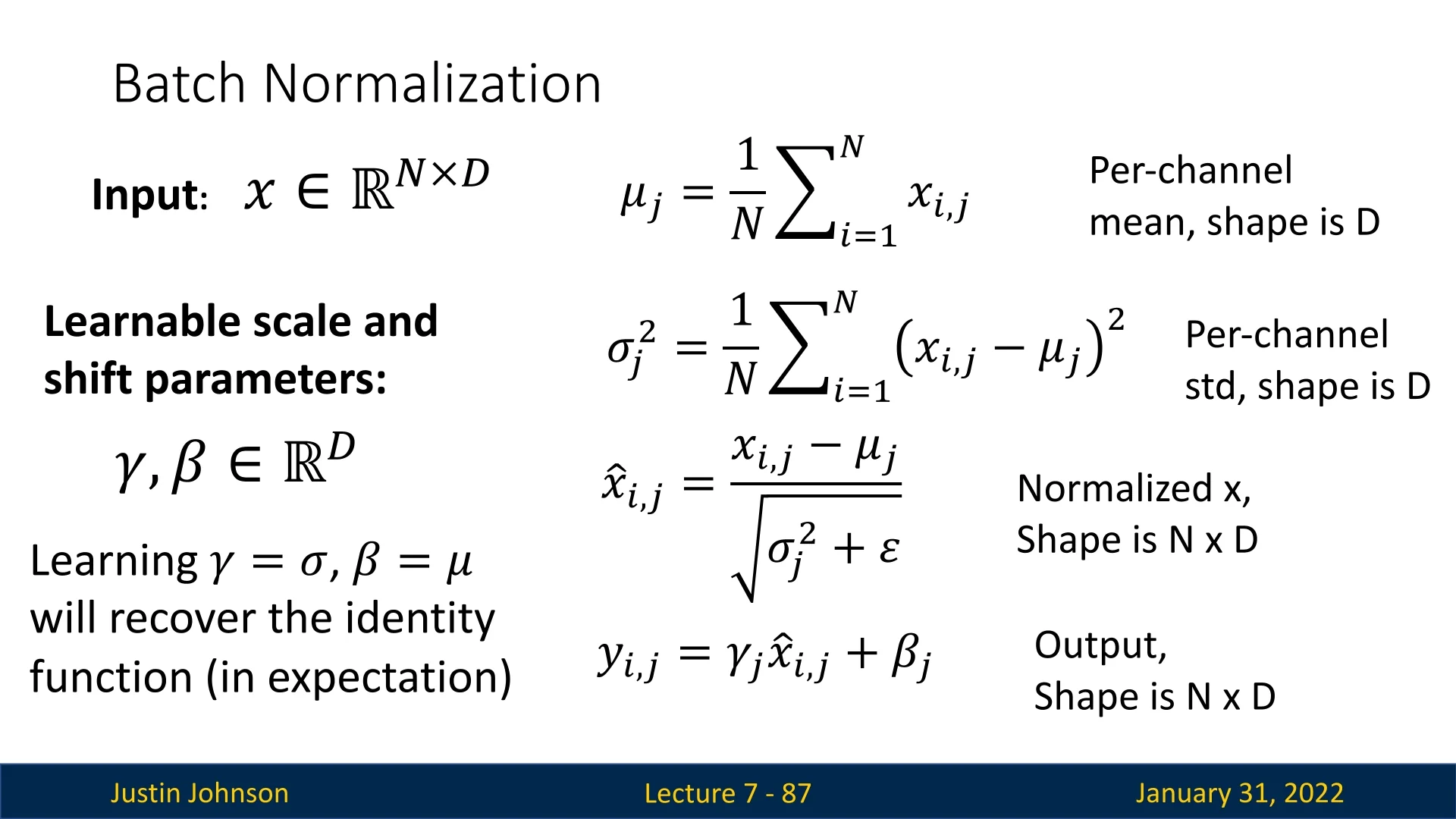

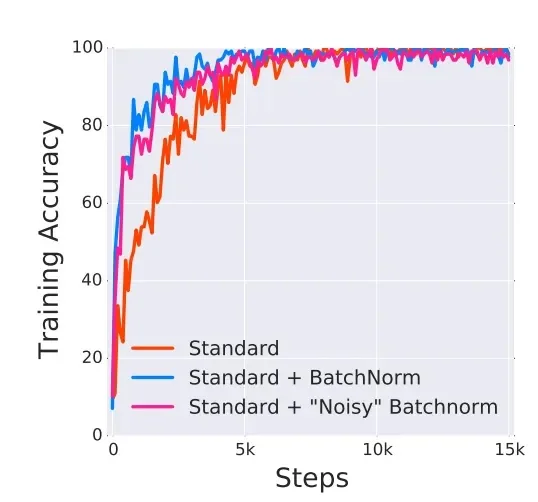

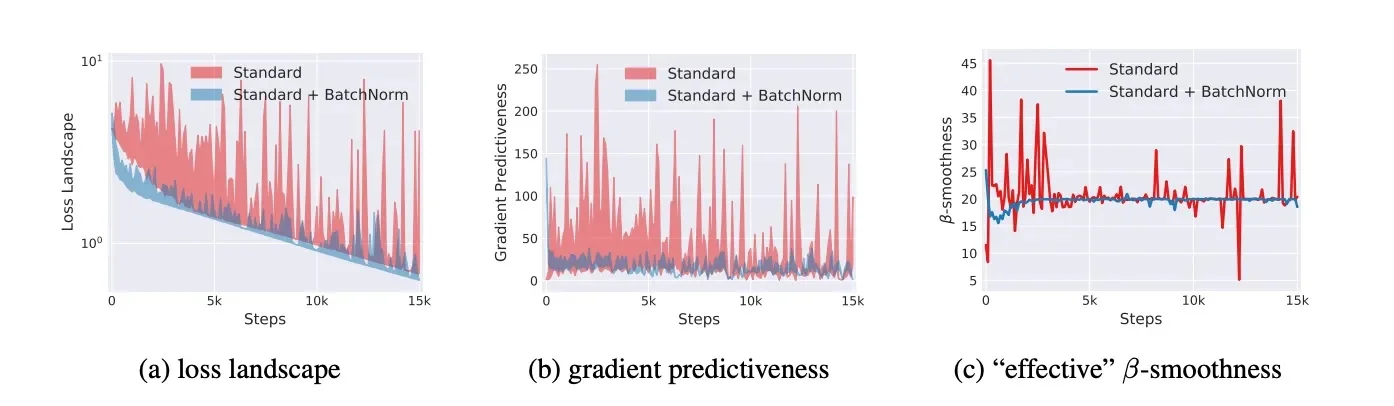

Negative and Large Output Values Standard image pixels range from \(0\) to \(255\), but convolution outputs can have negative values or exceed this range. This is not an issue because convolutional layers produce feature maps, not direct images. Although this isn’t an issue, neural networks sometimes keep these values in check through usage of techniques such as ’Batch Normalization’ that stabilize activations, greatly improving training efficiency.

In the rest of this lecture, we will explore these topics in depth, ensuring a complete understanding of how convolutional layers operate in modern neural networks.

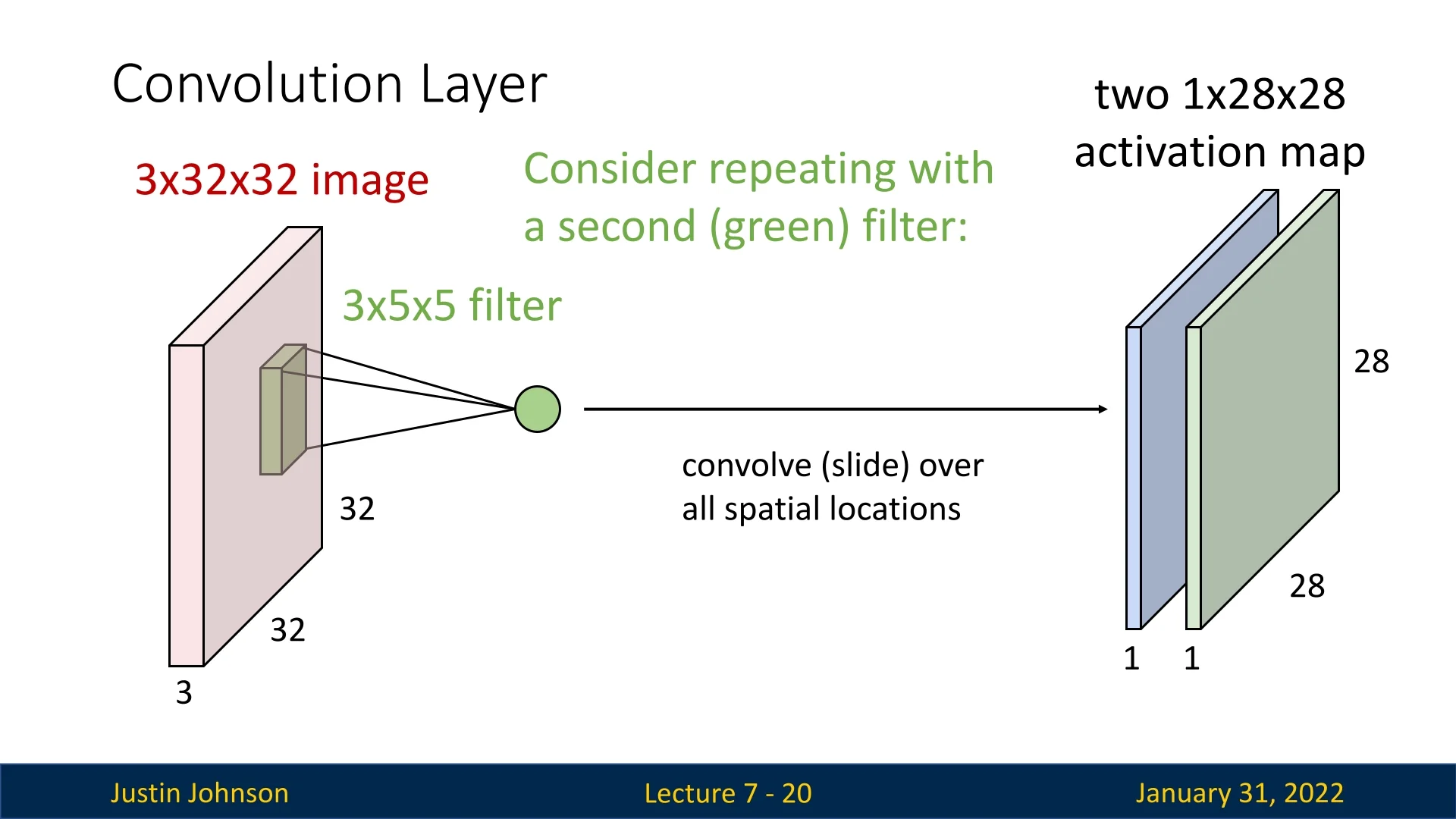

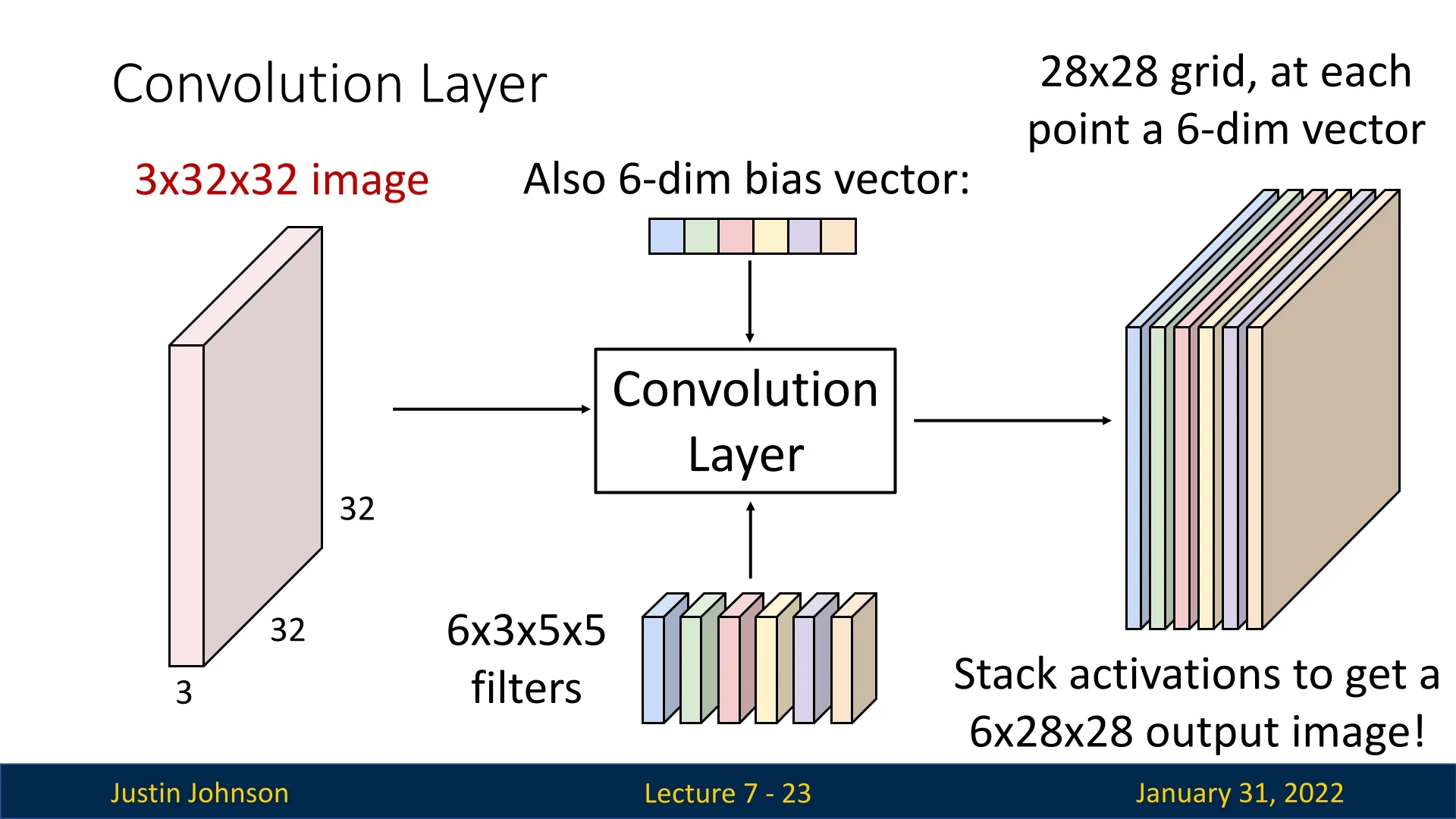

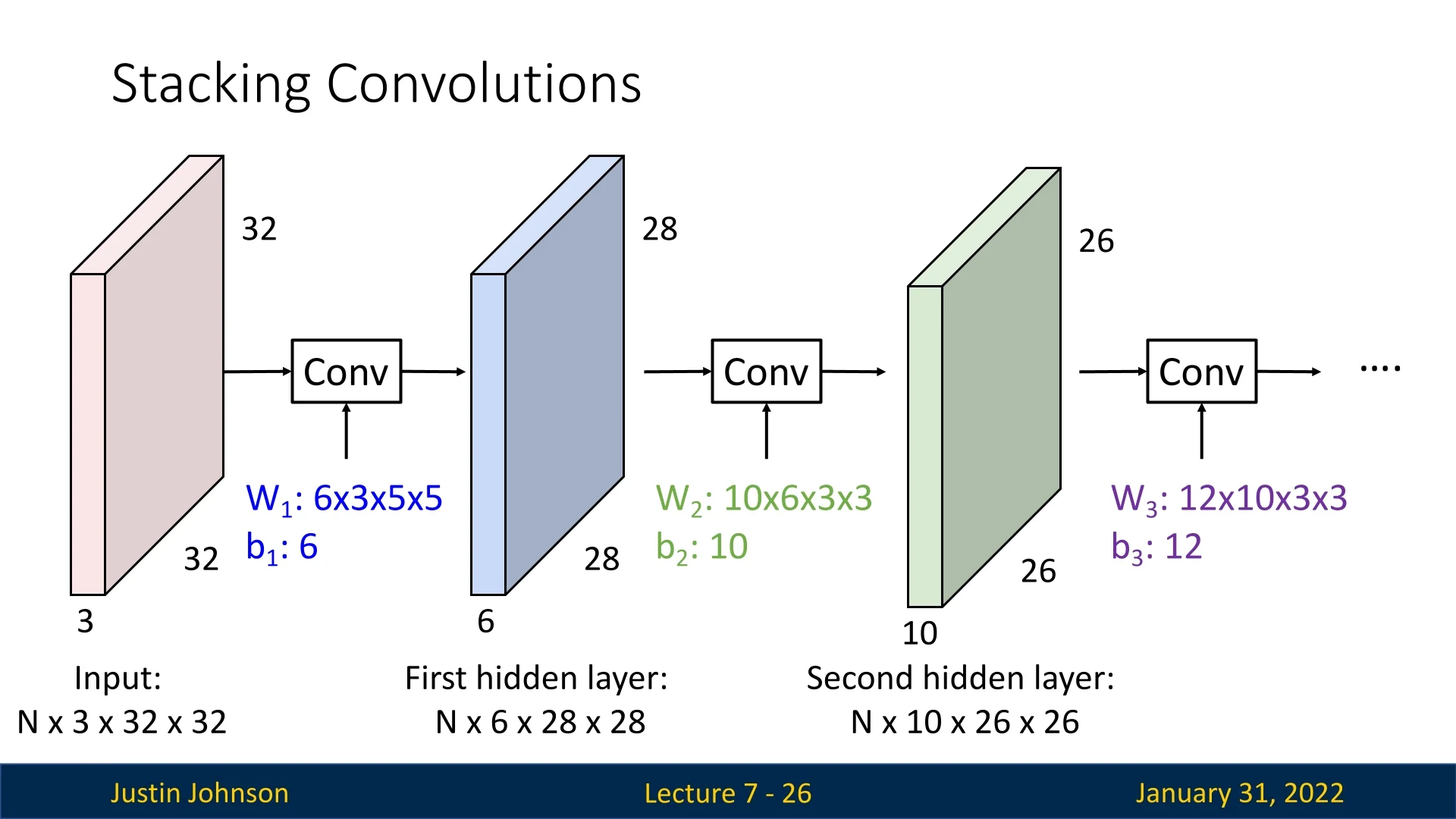

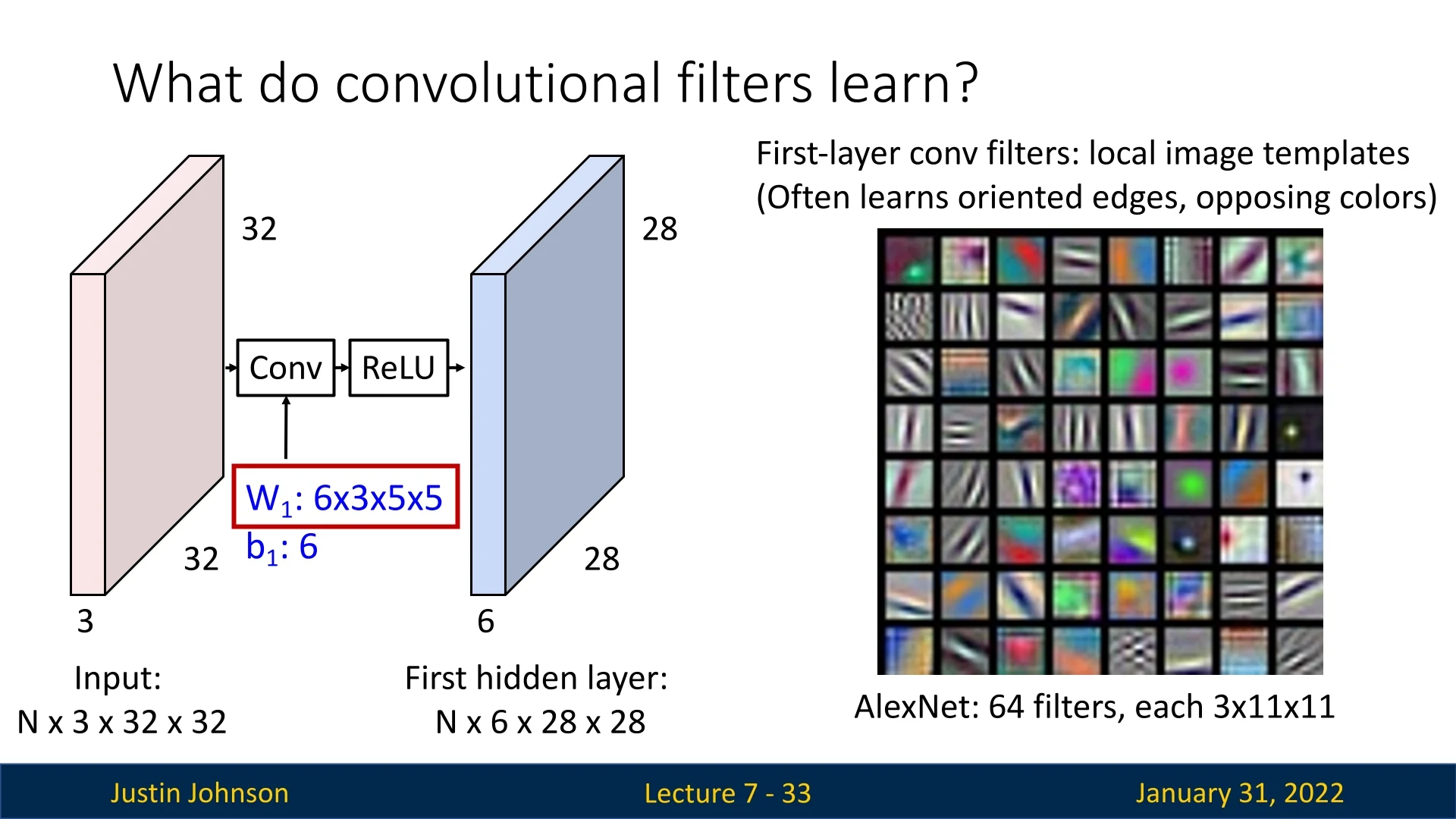

7.3.3 Multiple Filters and Output Channels

A convolutional layer can apply multiple filters, where each filter extracts a different feature from the input. The number of filters determines the number of output channels.

For example, if we apply 6 filters, each of size \( 3 \times 5 \times 5 \), to a \( 3 \times 32 \times 32 \) input image, the output consists of 6 activation maps, each of size \( 1 \times 28 \times 28 \). These maps can be stacked to form an output tensor of shape: \( 6 \times 28 \times 28.\)

7.3.4 Two Interpretations of Convolutional Outputs

The output of a convolutional layer can be viewed in two equivalent ways:

- 1.

- Stack of 2D Feature Maps: Each filter produces one activation map, so stacking all \(C_{\mbox{out}}\) maps yields a \((C_{\mbox{out}} \times H' \times W')\) volume.

- 2.

- Grid of Feature Vectors: Each spatial position \((h,w)\) in the output corresponds to a \(C_{\mbox{out}}\)-dimensional feature vector, representing learned features at approximately (convolutions without padding can reduce the spatial dim of the output tensor a bit) that location in the input tensor.

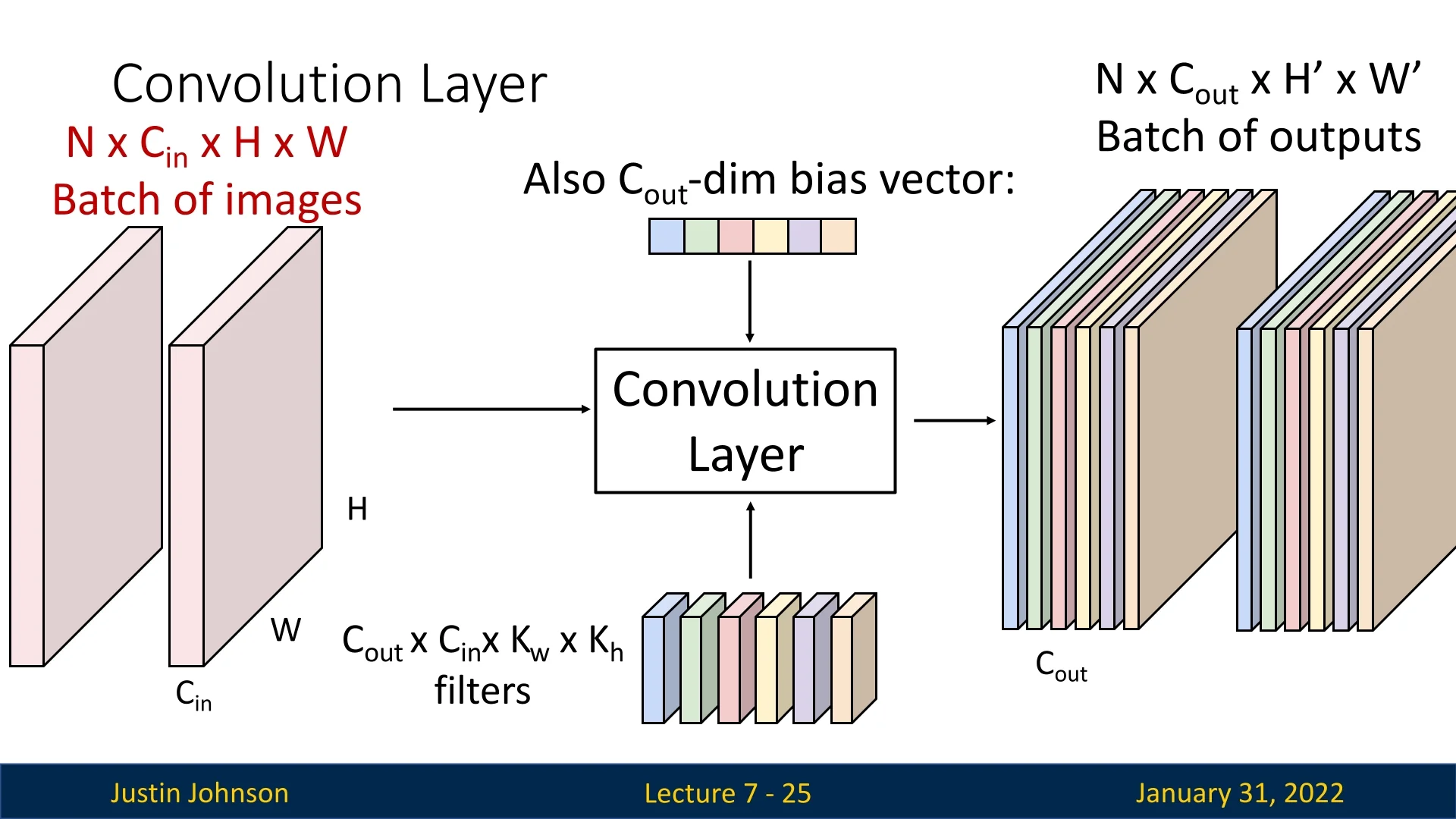

7.3.5 Batch Processing with Convolutional Layers

In practice, convolutional layers process batches of images. If we have a batch of \(N\) input images, each of shape \(C_{\mbox{in}} \times H \times W\), then the input tensor has shape: \[ N \times C_{\mbox{in}} \times H \times W. \] The corresponding output tensor has shape: \[ N \times C_{\mbox{out}} \times H' \times W'. \]

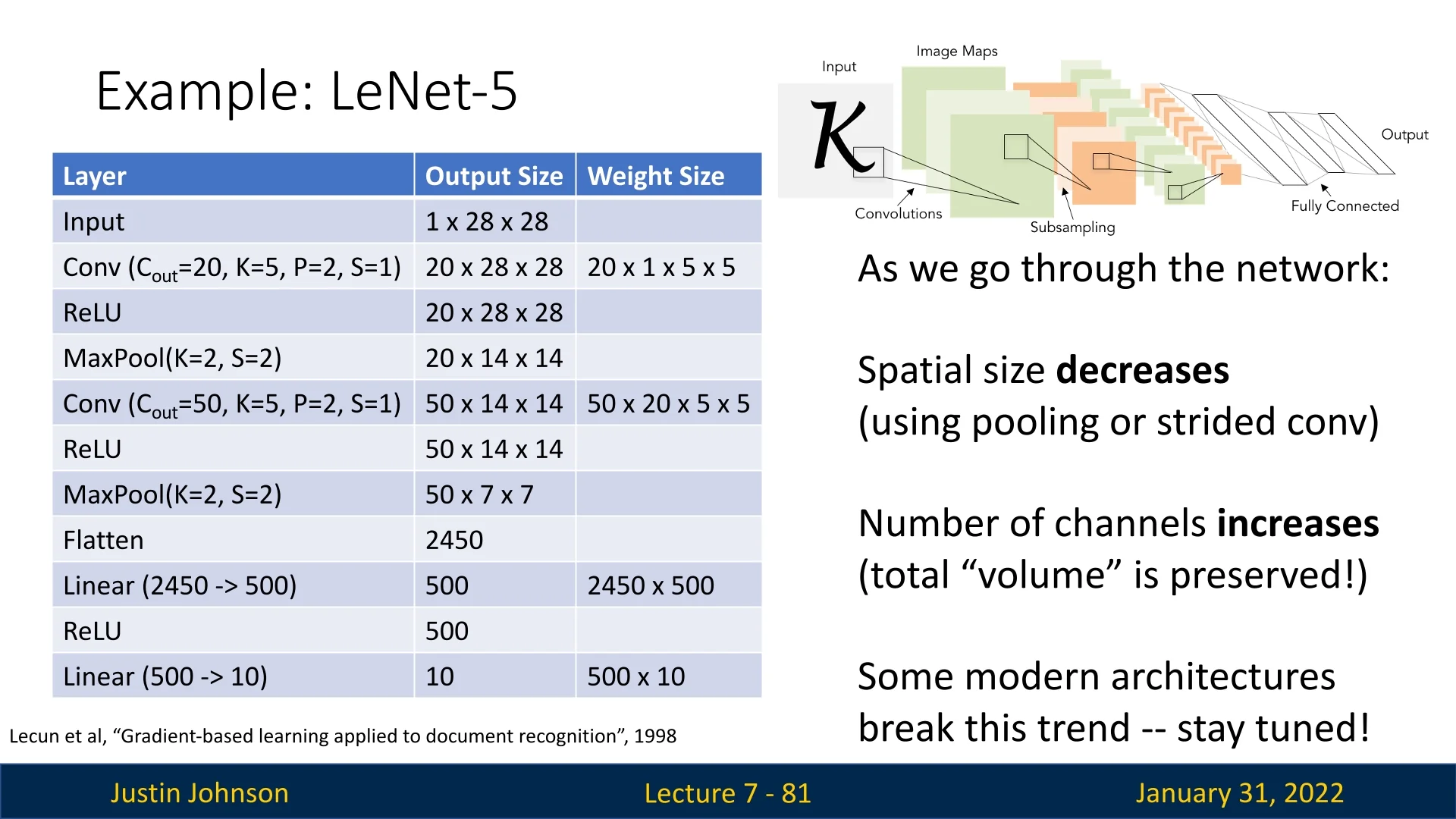

7.5 Building Convolutional Neural Networks

7.4.1 Stacking Convolutional Layers

With convolutional layers, we can construct a new type of neural network by stacking multiple convolutions sequentially. Unlike fully connected layers, where each neuron connects to every input feature, convolutional layers operate locally, extracting spatial features at each step.

The filters in convolutional layers are learned throughout the training process. They adjust dynamically to capture features useful for minimizing the network’s loss, just like the weights in fully connected layers. The output feature map after each convolution has:

- \( C_{\mbox{out}} \) channels (determined by the number of filters in that layer),

- A height \( H' \) and width \( W' \), which may differ from the input dimensions \( H \) and \( W \), depending on the use of padding and strides.

A common architectural pattern in convolutional networks is to reduce spatial dimensions while increasing the number of channels. The rationale for this is:

- Each channel can be seen as a learned feature representation, abstracting spatial patterns across layers.

- Reducing spatial dimensions while increasing channels allows the network to capture high-level patterns, moving from local details (e.g., edges) to global structures (e.g., entire objects).

- It allows neurons in deeper layers to gather information from a progressively larger region of the input, effectively expanding their receptive field. As we stack more convolutional and pooling layers, each neuron becomes responsive to a wider portion of the original image, enabling the network to capture increasingly large-scale structures (e.g., recognizing an entire cat’s face rather than just its whiskers)—a concept we will formalize later when discussing receptive fields.

7.4.2 Adding Fully Connected Layers for Classification

After passing through several convolutional layers, the output is a multi-channel feature representation of the input. To use this representation for classification or regression tasks, we typically:

- Flatten the feature maps into a 1D vector,

- Pass the vector through a fully connected (MLP) layer,

- Use a SoftMax activation (for classification).

This structure allows convolutional layers to act as feature extractors, and the final fully connected layers to perform decision-making based on the extracted features.

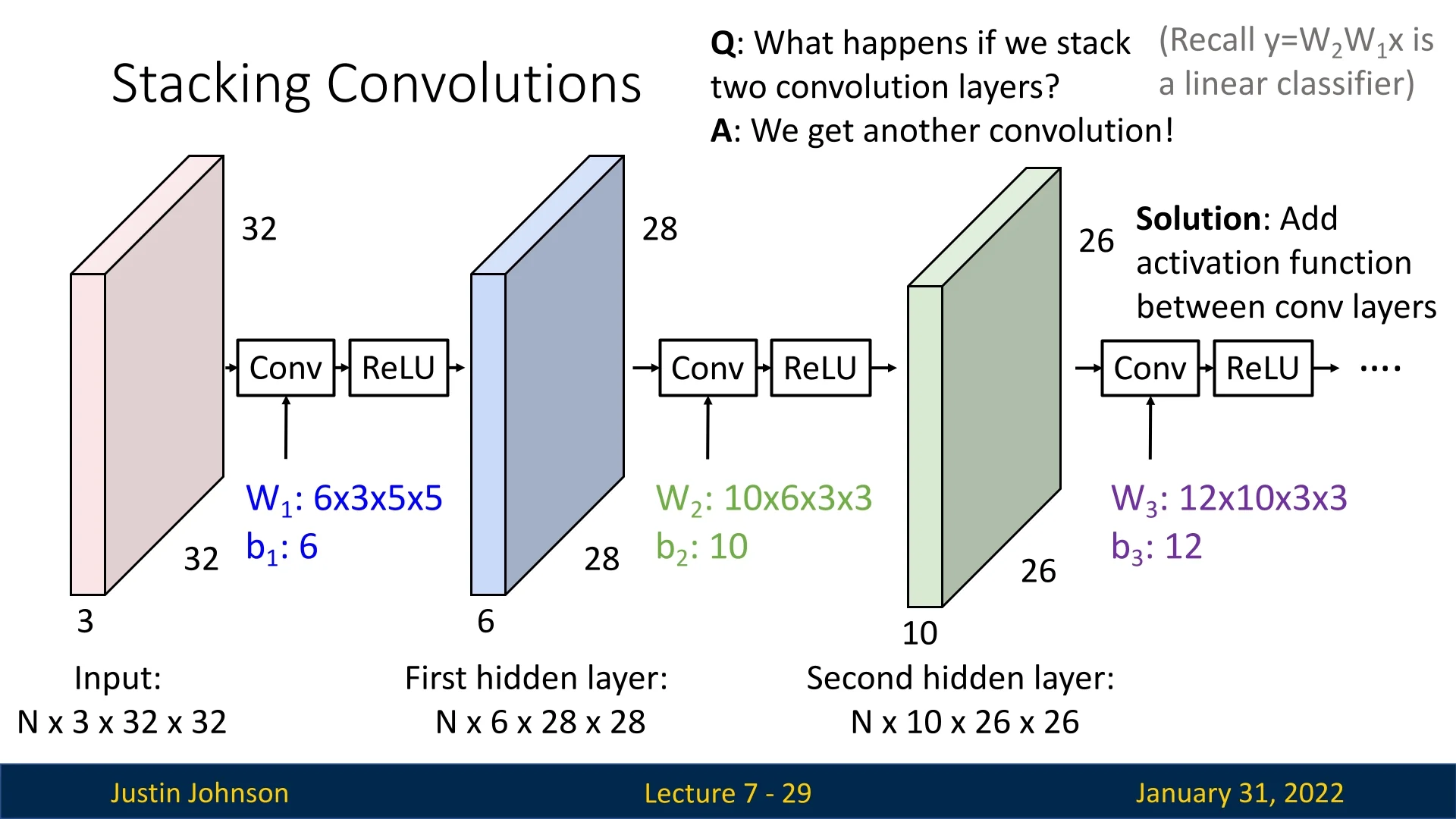

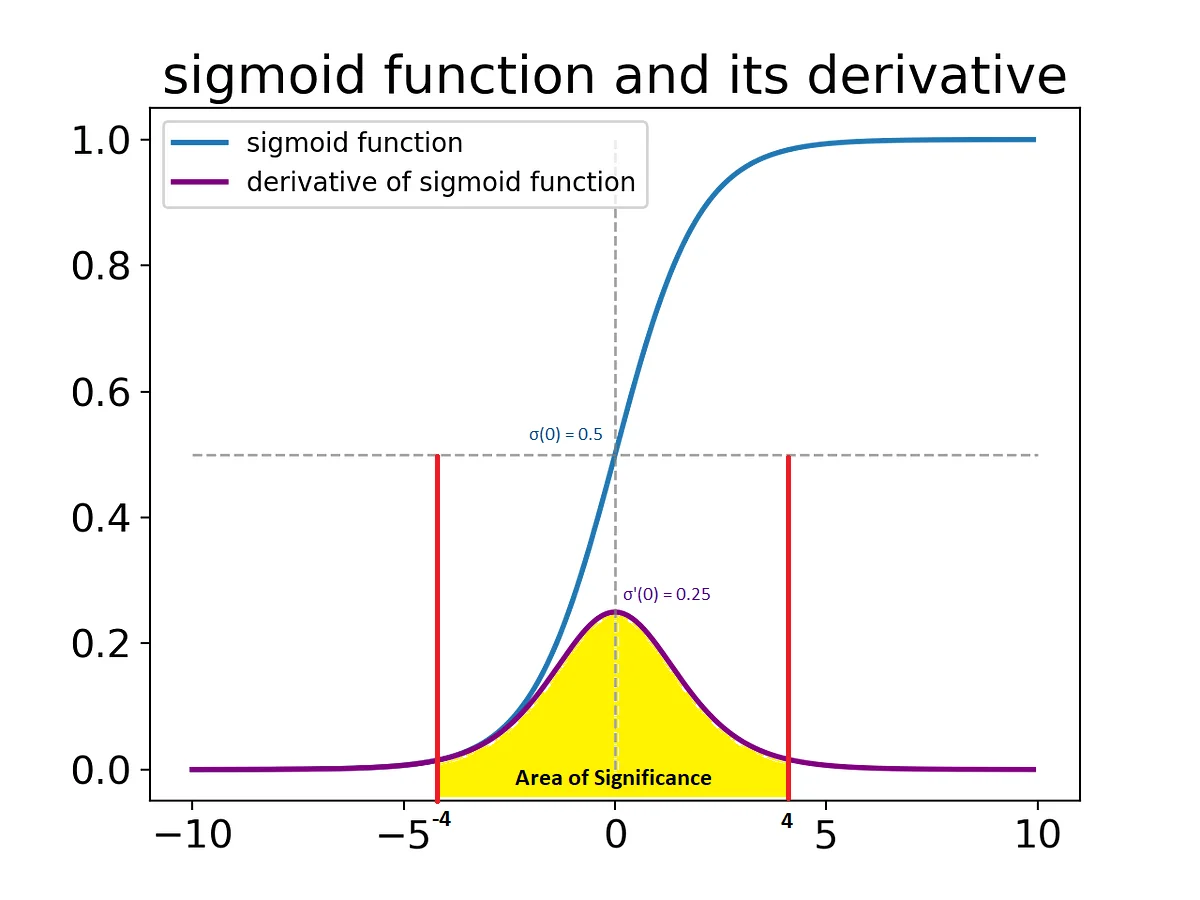

7.4.3 The Need for Non-Linearity

A major issue arises when stacking convolutional layers directly on top of each other: convolution itself is a linear operation. Recall from basic neural network theory that a sequence of linear transformations can always be reduced to a single linear transformation, meaning a network composed purely of stacked convolutional layers has limited expressive power.

Mathematically, consider a network with two convolutional layers: \[ X \xrightarrow {\mbox{Conv}_1} W_1 X \xrightarrow {\mbox{Conv}_2} W_2 W_1 X. \] Since both transformations are linear, the entire operation reduces to a single matrix multiplication. This is analogous to a multi-layer perceptron (MLP) without activation functions, which collapses into a single-layer network, greatly limiting its representational capacity.

The solution is to introduce non-linearity after each convolution. This is typically done using ReLU (Rectified Linear Unit) activations, which apply an element-wise transformation: \[ f(x) = \max (0, x). \] ReLU allows the network to model complex relationships by breaking the linearity of stacked layers, significantly increasing representational power.

7.4.4 Summary

- Stacking Convolutions allows deeper networks to learn increasingly abstract features.

- Reducing spatial dimensions while increasing channels helps capture global patterns in images.

- Flattening and adding fully connected layers enables classification and regression tasks.

- Introducing non-linearity between convolutional layers prevents the network from collapsing into a simple linear transformation, significantly enhancing representational capacity.

In the next sections, we will explore additional techniques such as pooling layers and batch normalization, which further improve the efficiency and stability of convolutional networks.

7.6 Controlling Spatial Dimensions in Convolutional Layers

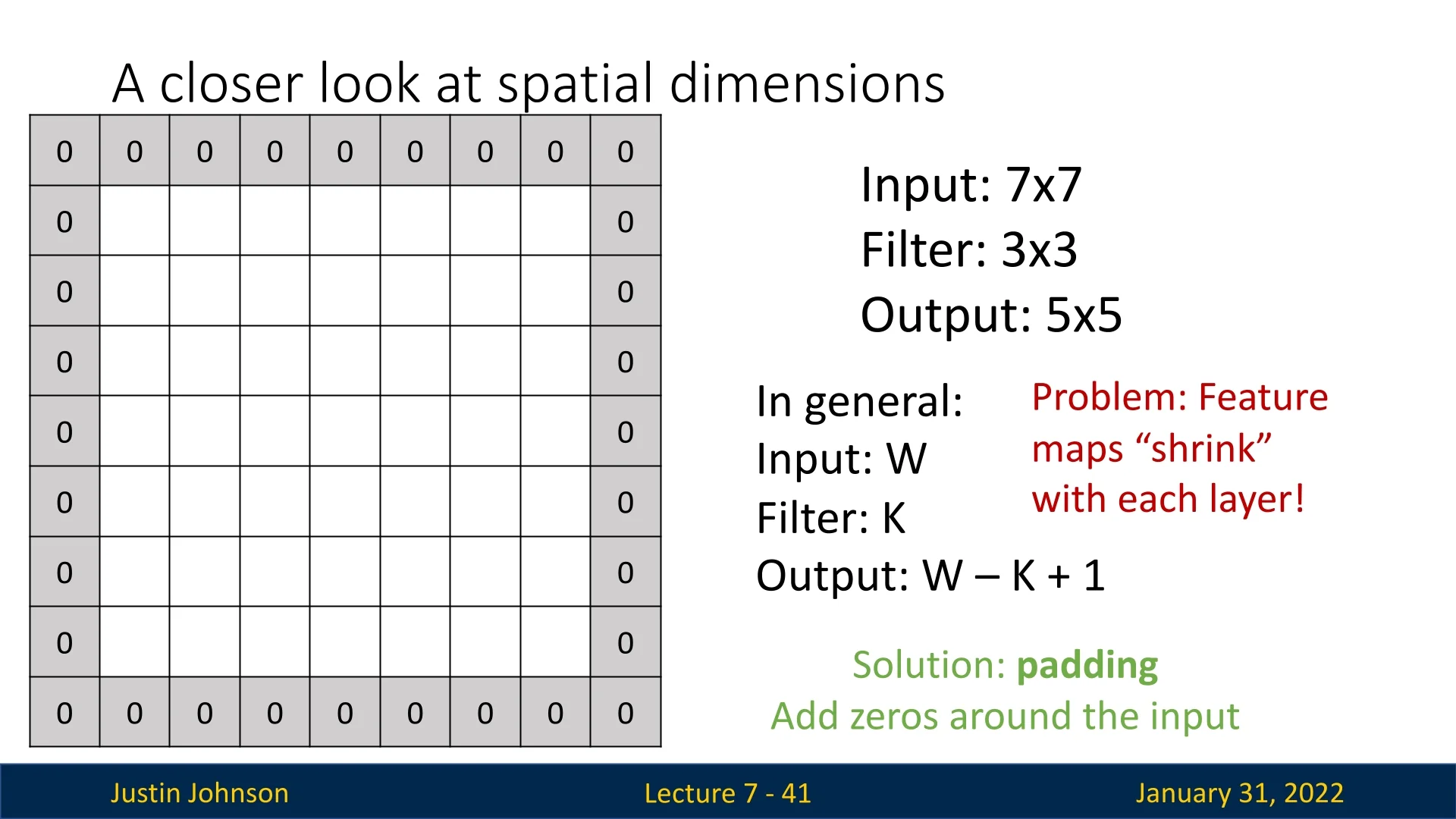

7.5.1 How Convolution Affects Spatial Size

When applying a convolutional filter to an input image, the spatial dimensions of the output shrink. If we start with a square input tensor of spatial size \( W \times W \) and apply a convolutional filter of size \( K \times K \), the output spatial size is given by: \[ W' = W - K + 1. \] For example, when we previously examined a \( 5 \times 5 \) patch of the Lotus image and applied a \( 3 \times 3 \) filter, the resulting feature map had dimensions: \[ 5 - 3 + 1 = 3 \times 3. \] This reduction in spatial size can become problematic as feature maps continue to shrink with deeper layers. If no corrective measures are taken, images may spatially collapse to an unrecognizable form, limiting the depth of our network.

7.5.2 Mitigating Shrinking Feature Maps: Padding

A common solution to prevent excessive spatial shrinkage is padding, where extra pixels are added around the borders of the input image before applying convolution. The most widely used approach is zero-padding, where padding pixels are filled with zeros. More advanced techniques, such as replication padding (copying the values of edge pixels) or reflection padding (mirroring the border values), are sometimes used in practice as well.

Choosing the Padding Size Padding introduces a new hyperparameter, \( P \), which determines how many pixels are added to the borders of the input. A commonly used setting is: \[ P = \frac {K - 1}{2}. \] This choice ensures that the output retains the same spatial dimensions as the input: \[ W' = W - K + 1 + 2P. \] For instance, using a \( 3 \times 3 \) filter with \( P = 1 \) ensures that a \( W \times W \) input produces a \( W \times W \) output. This technique, known as same padding, is widely used in deep convolutional architectures.

Preserving Border Information with Padding Another crucial role of padding is ensuring that the information at the borders of the image is not washed away as convolutional layers stack deeper in a network. Without padding, pixels near the borders of an image are involved in fewer computations than those in the center, leading to a loss of information at the edges. By adding padding, we allow convolutional filters to access meaningful contextual information even for edge pixels, improving feature extraction and preventing a bias toward central regions.

This effect is particularly relevant in tasks such as:

- Object Detection: Key features of an object may appear near the image borders, and padding ensures these features are processed adequately.

- Medical Imaging: In scans such as MRIs or X-rays, abnormalities may be located near the periphery. Padding helps ensure these regions receive equal importance.

- Segmentation Tasks: When performing image segmentation, retaining spatial consistency across the entire image is essential. Padding prevents distortions that could affect segmentation accuracy near the edges.

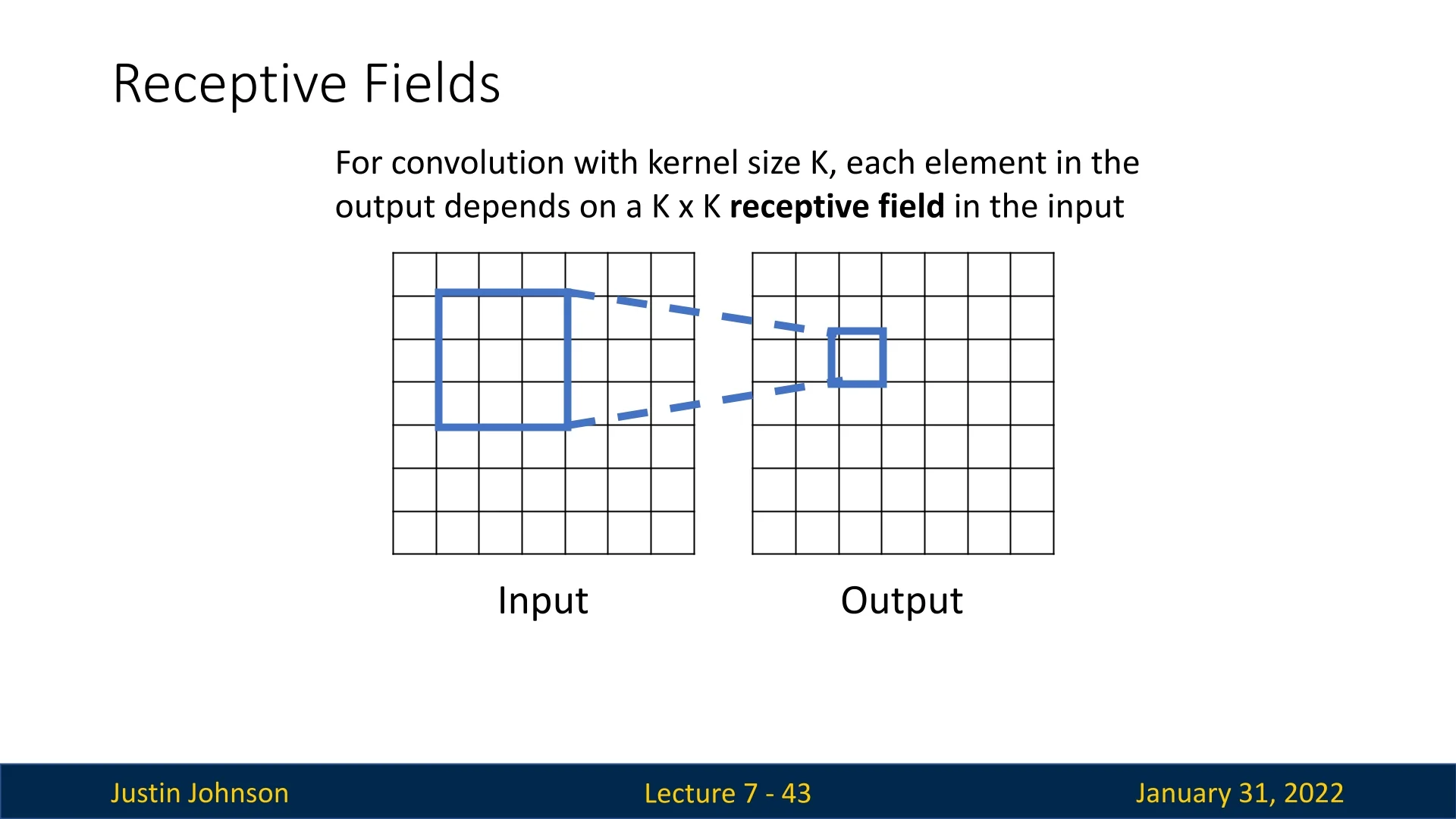

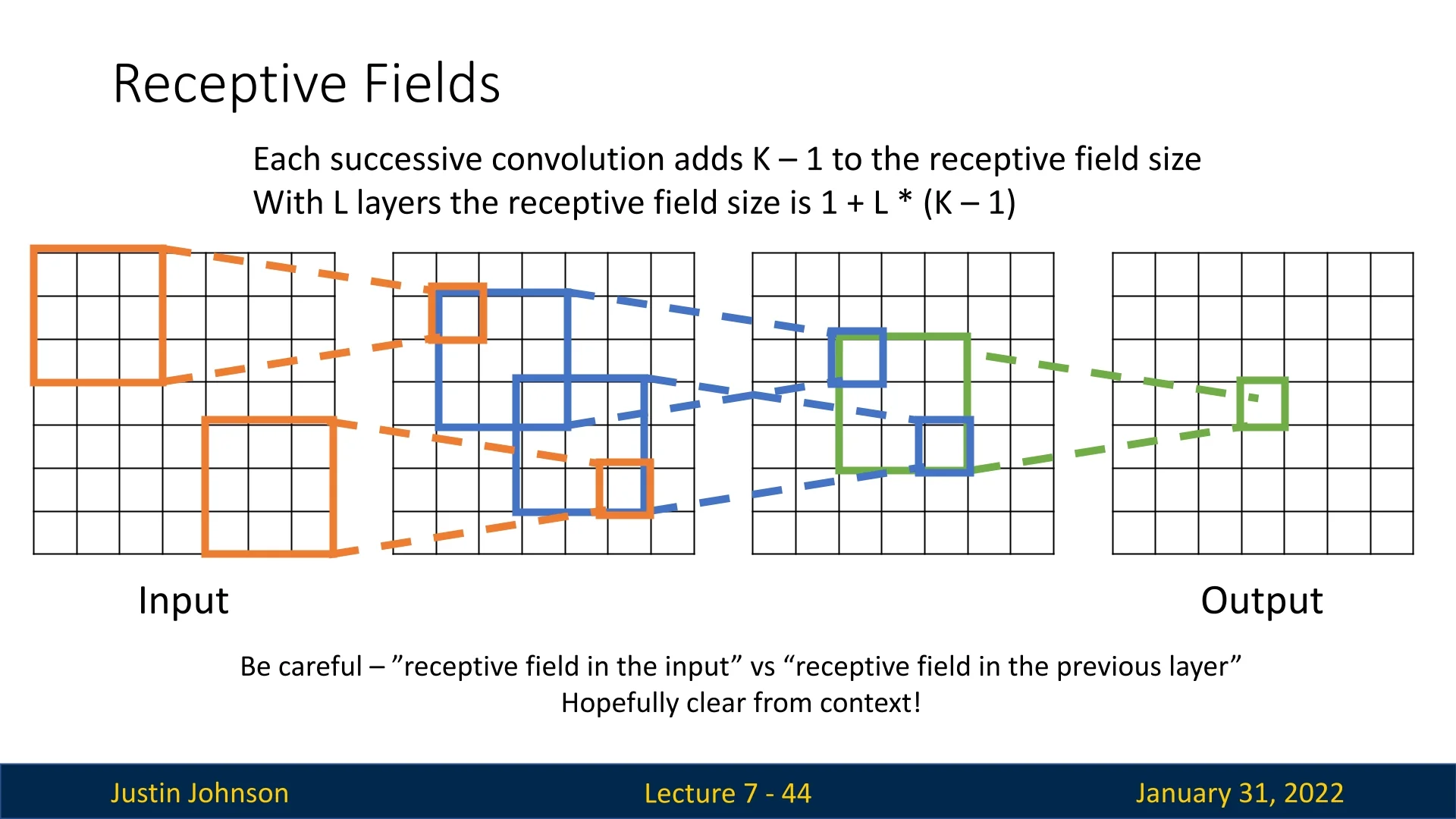

7.5.3 Receptive Fields: Understanding What Each Pixel Sees

Another way to analyze convolutional networks is by considering the receptive field of each output pixel. The receptive field of an output pixel represents the region in the original input that influenced its value.

Each convolution with a filter of spatial size \( K \times K \) expands the receptive field. With \( L \) convolutional layers, each having a \( K \times K \) filter, the receptive field size can be computed as: \[ \mbox{Receptive Field} = 1 + L \cdot (K - 1). \]

The Problem of Limited Receptive Field Growth

For deep networks, we want each output pixel to have access to a large portion of the original image. However, small kernels (e.g., \(3 \times 3\)) grow the receptive field slowly. Consider a \( 1024 \times 1024 \) image processed with a network using \( 3 \times 3 \) filters. We would need hundreds of layers before each output pixel “sees” the entire image.

Hence, we need to perform a more aggressive downsampling along the neural network. Some of the tools we can use for that purpose are strides and pooling layers. We’ll now cover both of these tools, starting with strides. As pooling layers are a different type of layer in the neural network, we’ll touch them after finishing with convolutions first.

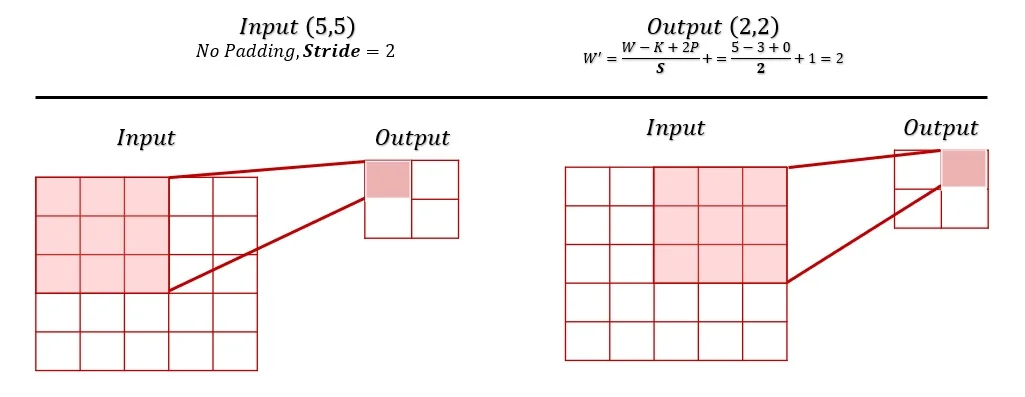

7.5.4 Controlling Spatial Reduction with Strides

Stride is another technique for managing spatial dimensions in convolutional networks. Instead of moving the filter one pixel at a time, we can define a stride \( S \), which determines how many pixels the filter shifts per step. Increasing the stride results in downsampling, reducing the output’s spatial dimensions: \[ W' = \frac {W - K + 2P}{S} + 1. \]

7.7 Understanding What Convolutional Filters Learn

7.6.1 MLPs vs. CNNs: Learning Spatial Structure

Traditional multilayer perceptrons (MLPs) learn weights for the entire image at once, often ignoring spatial structure. In contrast, convolutional neural networks (CNNs) learn filters that operate on small, localized patches, progressively building up more complex representations. This hierarchical feature extraction is key to CNNs’ ability to recognize objects and textures efficiently.

7.6.2 Learning Local Features: The First Layer

The first convolutional layer specializes in detecting fundamental image patterns:

- Local Receptive Fields: Each filter “sees” only a small region of the image (e.g., a \( 3 \times 3 \) patch). As a result, first-layer filters typically learn to detect edges, corners, color gradients, and small textures.

- Feature Maps: Each filter produces a feature map, highlighting areas where a learned pattern appears in the image. Strong activations indicate high similarity to the filter (e.g., bright responses for vertical edges).

7.6.3 Building More Complex Patterns in Deeper Layers

As the network deepens, convolutional layers process feature maps instead of raw pixels, enabling hierarchical feature composition. Each successive layer captures increasingly abstract patterns by integrating information from a growing receptive field.

Hierarchical Learning via Composition

- Early layers: Detect simple edges, gradients, and textures.

- Mid-layers: Combine early features into complex structures like shapes and object parts.

- Deepest layers: Recognize high-level semantic patterns, forming complete object representations.

Deeper networks enhance representational capacity by progressively composing features, transforming raw pixel data into hierarchical object representations. Each layer refines and abstracts information from previous layers, enabling more complex feature extraction. Empirical evidence, including visualization methods like DeepDream, confirms that deeper layers capture high-level semantic concepts. Modern architectures such as ResNets and DenseNets demonstrate that increased depth, when properly managed, improves feature learning and overall model performance.

7.8 Parameters and Computational Complexity in Convolutional Networks

Thus far, we have examined how convolutional layers operate, but an equally important consideration is their computational cost and learnable parameters. Unlike fully connected layers, it’s intuitive that convolutional layers significantly reduce the number of parameters, but what about computational operations?

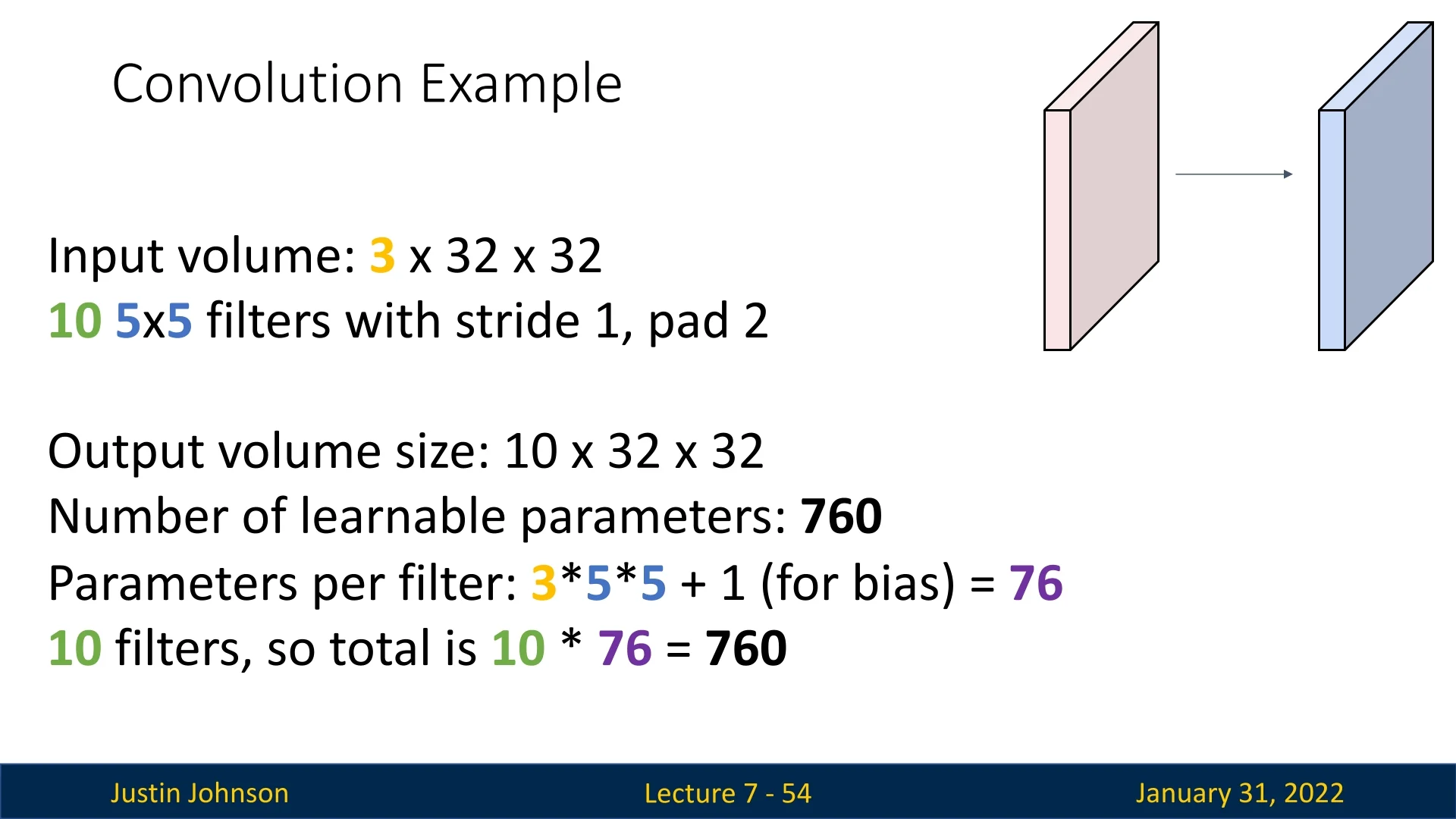

7.7.1 Example: Convolutional Layer Setup

To understand these calculations, consider a single convolutional layer with the following configuration:

- Input volume: \(3 \times 32 \times 32\) (an RGB image with height 32, width 32, and 3 channels).

- Number of filters: 10.

- Filter size: \(3 \times 5 \times 5\).

- Stride: 1.

- Padding: Same padding (\(P = 2\)), preserving spatial dimensions.

7.7.2 Output Volume Calculation

With same padding and stride 1, the spatial dimensions remain: \[ H' = W' = \frac {32 + 2(2) - 5}{1} + 1 = 32. \] Since we have 10 filters, the final output volume is: \[ 10 \times 32 \times 32. \]

7.7.3 Number of Learnable Parameters

Each filter consists of \(3 \times 5 \times 5 = 75\) weights, plus one bias parameter: \[ \mbox{Parameters per filter} = 75 + 1 = 76. \] With 10 filters in the layer: \[ \mbox{Total parameters} = 76 \times 10 = 760. \] This is a significant reduction compared to fully connected layers, where each neuron connects to all input elements.

7.7.4 Multiply-Accumulate Operations (MACs)

The computational cost of a convolutional layer is typically measured in Multiply-Accumulate Operations (MACs), named after their two-step process: multiplying two values and accumulating the result into a running sum. This operation is fundamental in digital signal processing (DSP) and neural network computations, as it efficiently performs weighted summations required for convolutions.

MACs Calculation: The total number of positions in the output volume is: \[ 10 \times 32 \times 32 = 10,240. \] Each spatial position is computed via a dot product between the filter and the corresponding input region, requiring: \[ 3 \times 5 \times 5 = 75 \] MACs per position. Thus, the total number of MACs for the layer is: \[ 75 \times 10,240 = 768,000. \]

7.7.5 MACs and FLOPs

In computational performance metrics, MACs are often translated into Floating-Point Operations (FLOPs). The definition of FLOPs varies depending on hardware:

- Some systems count each MAC as 2 FLOPs (one multiply + one add).

- Others treat a fused MAC as a single FLOP.

Thus, this layer requires:

- \(768,000\) FLOPs (if MACs are counted as one FLOP).

- \(1,536,000\) FLOPs (if each MAC counts as two FLOPs).

7.7.6 Why Multiply-Add Operations (MACs) Matter

MACs provide a key measure of a neural network’s efficiency:

- Computational Cost: The fewer MACs, the faster the network runs, making inference more efficient.

- Design Considerations: Balancing accuracy and computational cost is crucial, and MACs provide a key metric for optimizing architectures.

Even though convolutional networks use fewer parameters than fully connected networks, their computational cost (measured in MACs) can be high, necessitating careful architecture design.

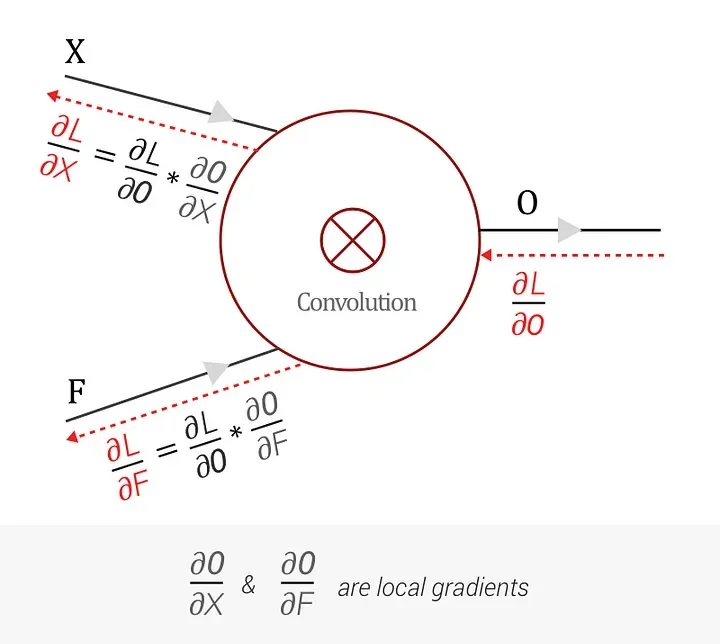

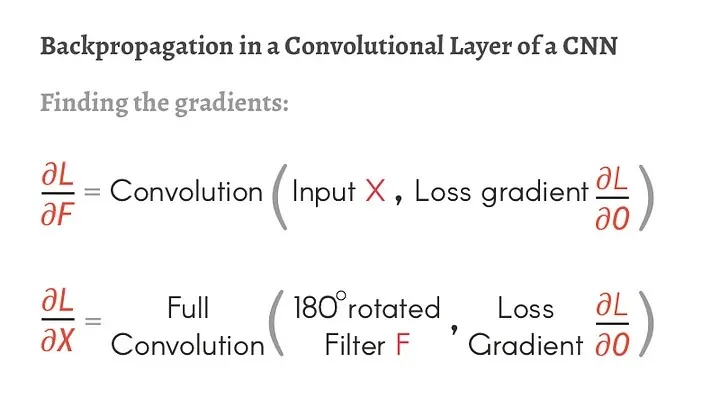

Enrichment 7.8.7: Backpropagation for Convolutional Neural Networks

This enrichment section is adapted from the Medium article by Pavithra Solai [579], providing a clear illustration of backpropagation in convolutional layers.

Key Idea: Convolution as a Graph Node In a computational graph, each convolutional layer receives an upstream gradient \(\frac {dL}{dO}\), where \(O\) is the output of the convolution: \[ O = X \circledast F, \] with \(X\) denoting the input tensor (patch) and \(F\) the convolution filter.

Using the chain rule, we can write: \[ \frac {dL}{dX} = \frac {dL}{dO} \times \frac {dO}{dX}, \quad \frac {dL}{dF} = \frac {dL}{dO} \times \frac {dO}{dF}, \] where \(\tfrac {dO}{dX}\) and \(\tfrac {dO}{dF}\) are the local gradients from the convolution operation, and \(\tfrac {dL}{dO}\) is the upstream gradient arriving from deeper layers.

Computing \(\tfrac {dO}{dF}\) Consider a \((3\times 3)\) input patch \(X\) and a \((2\times 2)\) filter \(F\):

\[ X = \begin {bmatrix} X_{11} & X_{12} & X_{13}\\ X_{21} & X_{22} & X_{23}\\ X_{31} & X_{32} & X_{33} \end {bmatrix},\quad F = \begin {bmatrix} F_{11} & F_{12}\\ F_{21} & F_{22} \end {bmatrix}. \] When convolved, the first element \(O_{11}\) is: \[ O_{11} = X_{11}F_{11} + X_{12}F_{12} + X_{21}F_{21} + X_{22}F_{22}. \] Taking derivatives: \[ \tfrac {\partial O_{11}}{\partial F_{11}} = X_{11},\quad \tfrac {\partial O_{11}}{\partial F_{12}} = X_{12},\quad \tfrac {\partial O_{11}}{\partial F_{21}} = X_{21},\quad \tfrac {\partial O_{11}}{\partial F_{22}} = X_{22}. \] Repeating for \(O_{12},O_{21},O_{22}\) yields similar terms. Thus, \(\tfrac {dL}{dF_i}\) arises from summing elementwise gradients over all spatial locations: \[ \tfrac {dL}{dF_i} = \sum _{k=1}^{M} \tfrac {dL}{dO_k} \;\tfrac {\partial O_k}{\partial F_i}. \] Effectively, \(\tfrac {dL}{dF}\) can be interpreted as a convolution of \(X\) with \(\tfrac {dL}{dO}\).

Computing \(\tfrac {dL}{dX}\) A similar argument applies to \(\tfrac {dL}{dX}\). In fact, \[ \tfrac {dL}{dX} = F^\star \;\circledast \; \tfrac {dL}{dO}, \] where \(F^\star \) is a 180-degree rotation of the filter \(F\).

Full details and visual examples can be found in [579], which provide additional insights into the math and coding approach for convolutional backprop.

Enrichment 7.9: Parameter Sharing in Convolutional Neural Networks

Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) leverage parameter sharing to drastically reduce the number of parameters while maintaining high representational power. The key assumption behind parameter sharing is that features learned at one spatial location are also useful at other locations, which is particularly beneficial for images with translational invariance.

Enrichment 7.9.1: Parameter Sharing in CNNs vs. MLPs

Unlike Multilayer Perceptrons (MLPs), which assign independent weights to each input neuron, CNNs apply the same set of weights across different spatial locations. In an MLP, each layer has a fully connected structure, leading to a number of parameters that scales quadratically with input size. In contrast, CNNs use convolutional filters that slide across the image, sharing parameters across spatial positions. This difference enables CNNs to efficiently learn spatial hierarchies while significantly reducing computational complexity.

Enrichment 7.9.2: Motivation for Parameter Sharing

Parameter sharing is motivated by several key advantages:

- Reducing Parameters: Instead of learning independent weights for every neuron, CNNs share a common set of weights across the spatial dimensions. This significantly reduces the number of parameters and makes training more efficient.

- Translational Invariance: If detecting a specific feature (e.g., an edge, a texture) is useful in one part of the image, it should also be useful elsewhere. This property aligns well with the structure of natural images.

- Learning Efficient Representations: By sharing parameters across spatial locations, the model learns generalized feature detectors that work across an image rather than overfitting to specific pixel locations.

Enrichment 7.9.3: How Parameter Sharing Works

The neurons in a convolutional layer are constrained to use the same set of weights and biases across different spatial locations.

- Mathematically, for an input image \( X \), a convolutional kernel \( W \), and a bias term \( b \), the convolution operation at location \( (i,j) \) is computed as: \begin {equation} Y_{ij} = \sum _{m} \sum _{n} W_{mn} X_{i+m, j+n} + b. \end {equation}

- The same filter \( W \) is applied across all positions, ensuring that the network learns spatially invariant representations.

Enrichment 7.9.4: When Does Parameter Sharing Not Make Complete Sense?

While parameter sharing is a powerful technique, there are scenarios where it may not be fully appropriate:

- Structured Inputs: If the input images have a specific centered structure, different spatial locations may require distinct features. For example, in datasets where objects (e.g., faces) are always centered, features extracted from the left and right sides of an image may need to be different.

- Example: Face Recognition: In facial recognition, eyes, noses, and mouths appear in predictable locations. It may be beneficial to learn different filters for different regions (e.g., eye-specific features vs. mouth-specific features), rather than enforcing parameter sharing across all positions. An example: [597].

- Medical Imaging: In medical scans (e.g., MRIs or CT scans), abnormalities may occur at specific spatial locations. Detecting a tumor in a specific organ may require distinct filters tailored to that region rather than using the same features everywhere. An example: [365].

- Autonomous Driving: Road scenes contain structured components such as sky, road, and vehicles, each of which may require specialized filters based on their typical locations in the image.

Enrichment 7.9.5: Alternative Approaches When Parameter Sharing Fails

In cases where parameter sharing is not ideal, alternative architectures can be used:

Enrichment 7.9.5.1: Locally-Connected Layers

Unlike standard convolutional layers, locally-connected layers do not share weights across spatial positions. Instead, each neuron in the layer learns a unique set of weights, allowing the network to specialize different feature detectors for different spatial regions. This is particularly useful when spatial position conveys meaning, such as in medical imaging, facial recognition, and structured object recognition.

Enrichment 7.9.5.2: Understanding Locally-Connected Layers

The concept of locally-connected layers extends from convolutional layers but removes the translational invariance constraint. Instead of applying the same filter everywhere, each spatial position has its own learnable filter. Mathematically, this is represented as: \begin {equation} Y_{ij} = \sum _{m} \sum _{n} W_{mn}^{(ij)} X_{i+m, j+n} + b_{ij}, \end {equation} where each weight matrix \( W^{(ij)} \) and bias \( b_{ij} \) is unique to its corresponding spatial position \( (i,j) \). This allows for spatially varying feature extraction.

Enrichment 7.9.5.3: Limitations of Locally-Connected Layers

Despite their advantages, locally-connected layers come with several drawbacks:

- Increased Parameter Count: Unlike convolutional layers, where the same filters are reused, locally-connected layers require separate filters for each spatial position, leading to a substantial increase in parameters.

- Higher Computational Cost: Training and inference become more expensive due to the increased number of independent weights.

- Reduced Generalization: By removing parameter sharing, the model may require more data to learn robust features that generalize well.

While locally-connected layers can be powerful for structured image processing tasks, they are often used selectively in deep learning architectures.

In practice, hybrid models that combine convolutional and locally-connected layers provide a balance between generalization and spatial specificity, and are sometimes used in practice for the particular situations in which full parameter-sharing approach doesn’t make total sense.

Enrichment 7.9.5.4: Hybrid Approaches

Some architectures combine parameter-sharing layers with locally-connected layers to balance generalization and location-specific feature learning. For example, early layers may use standard convolutional layers to learn general features, while later layers may incorporate locally-connected layers to capture region-specific information.

Enrichment 7.9.5.5: A Glimpse at Attention Mechanisms

Another alternative to parameter sharing is self-attention, which dynamically determines how important different regions of an input are to each other. This mechanism, employed in Vision Transformers (ViTs), allows for flexible representation learning beyond the fixed structure of convolutional filters. We will explore self-attention in detail in later chapters.

Parameter sharing is a key ingredient in the success of CNNs, enabling them to generalize effectively while keeping models computationally efficient. However, in cases where spatial locations carry distinct feature importance, alternative approaches such as locally-connected layers or attention mechanisms may be required.

7.10 Special Types of Convolutions: 1x1, 1D, and 3D Convolutions

Beyond standard 2D convolutions, different variations exist to address various computational and structural needs in deep learning models. In this section, we explore 1x1 convolutions for feature adaptation, 1D convolutions for sequential data, and 3D convolutions for volumetric and spatiotemporal processing.

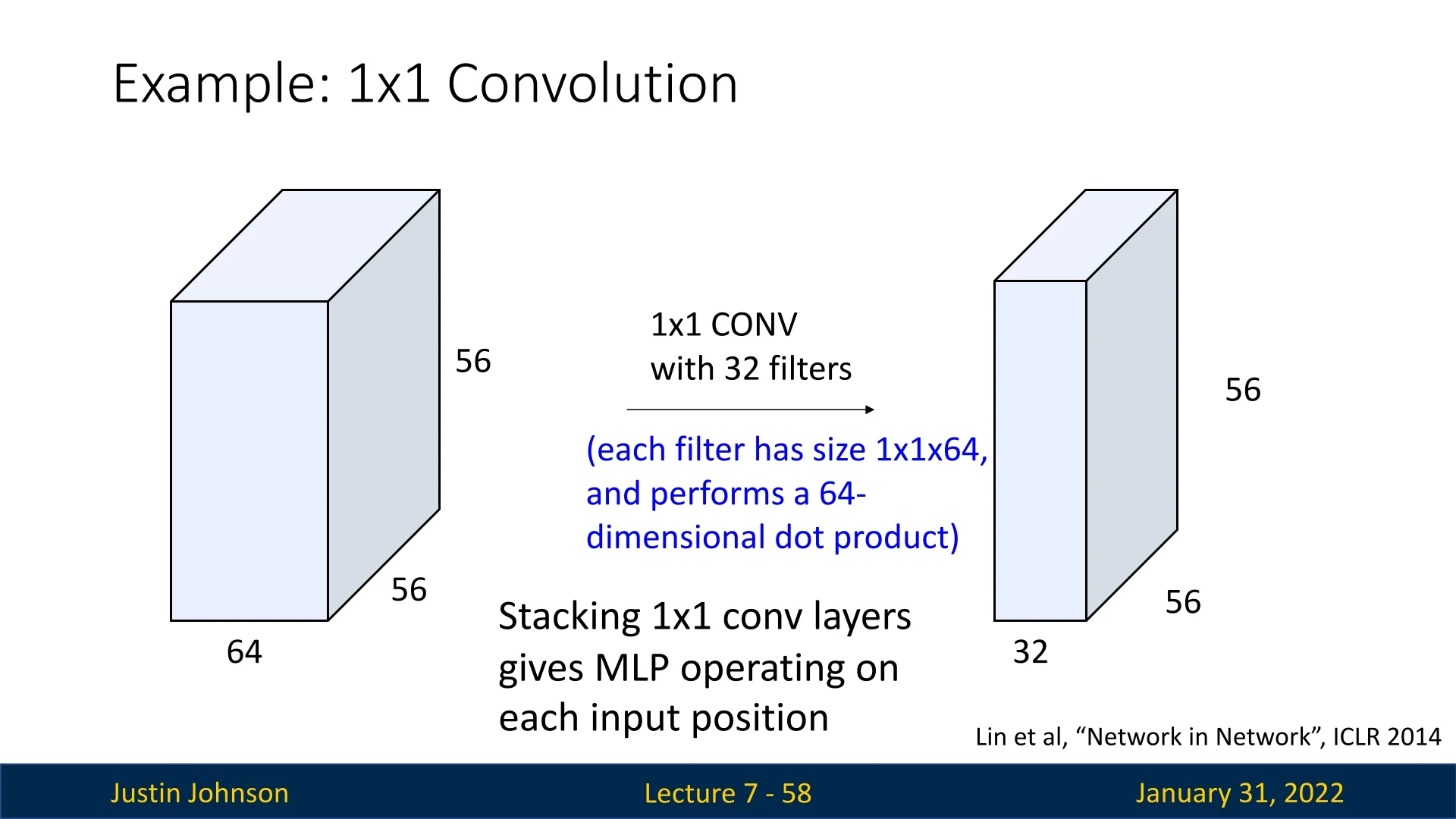

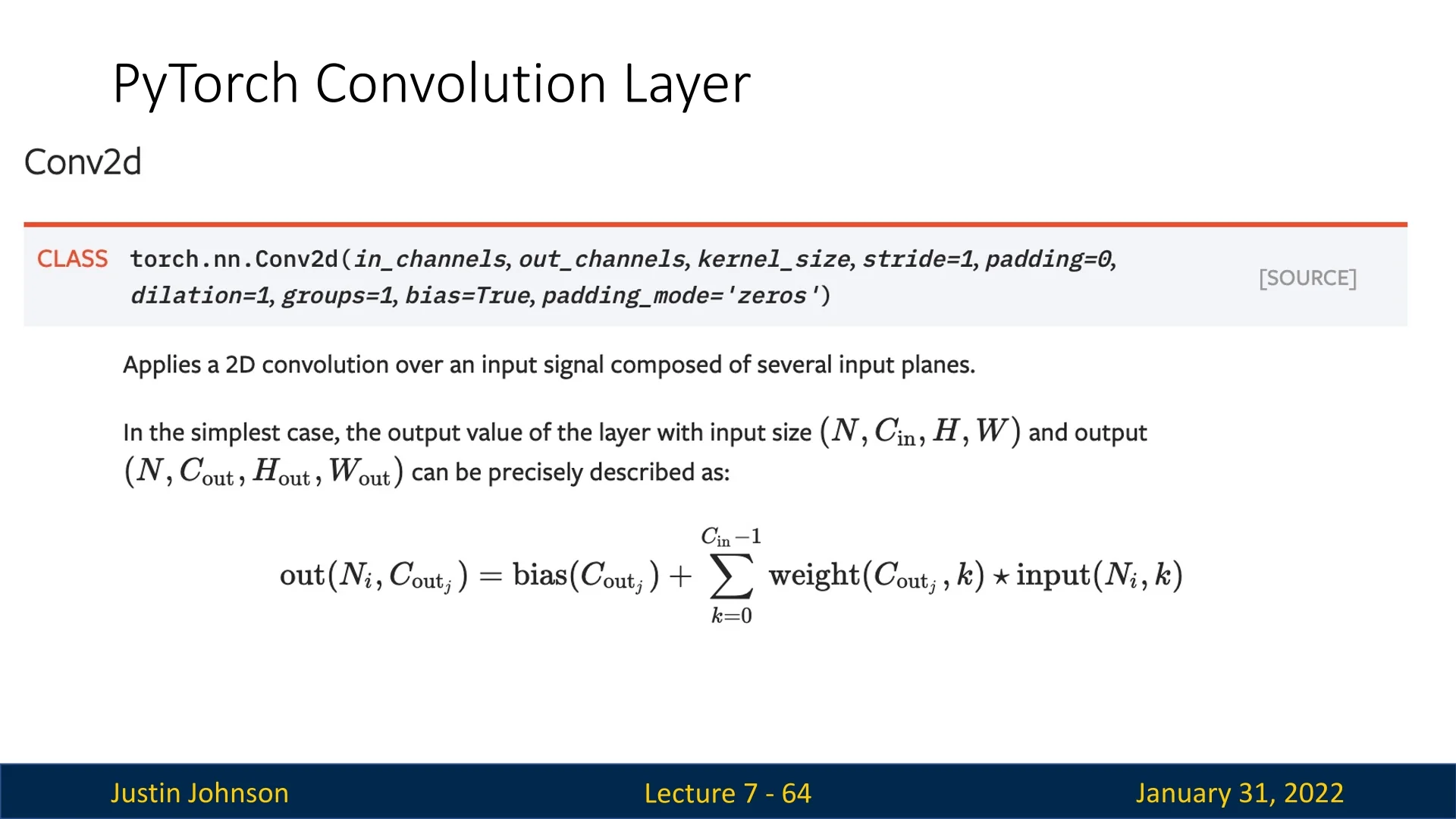

7.8.1 1x1 Convolutions

A 1x1 convolution applies a kernel of size \(1 \times 1\), meaning each filter operates on a single spatial position but across all input channels. Unlike traditional convolutions, which aggregate information from neighboring pixels, 1x1 convolutions focus solely on depth-wise transformations.

Dimensionality Reduction and Feature Selection

One common use of 1x1 convolutions is reducing computational complexity. For example, suppose a convolutional layer outputs an activation map of shape \( (N, F, H, W) \), where:

- \( N \) is the batch size,

- \( F \) is the number of input channels,

- \( H, W \) are the spatial dimensions.

If we apply a layer with \( F_1 \) 1x1 filters, the output shape becomes \( (N, F_1, H, W) \), effectively modifying the number of feature channels without altering spatial dimensions.

Efficiency of 1x1 Convolutions as a Bottleneck

A common strategy in modern CNN architectures (e.g., ResNet) is to introduce a 1x1 convolution before (and sometimes after) a more expensive 3x3 convolution, temporarily reducing the number of channels on which the 3x3 operates. This design, often called a bottleneck, lowers both parameter counts and floating-point operations (FLOPs) while preserving representational capacity.

Example: Transforming 256 Channels to 256 Channels with a 3x3 Kernel. Suppose the input has 256 channels of spatial size \(64\times 64\), and we want an output of 256 channels with spatial size \(62\times 62\) (no padding, stride 1).

- 1.

- Direct 3x3 Convolution.

- Parameters: Each of the 256 output channels has \((256 \times 3 \times 3)\) weights plus 1 bias. Total: \[ 256 \times (256 \times 3 \times 3) + 256 \;\approx \; 590{,}080. \]

- FLOPs: The output shape is \(256 \times 62 \times 62\), i.e. \(984{,}064\) output positions. Each position requires \((256 \times 3 \times 3) = 2304\) multiply-adds, giving approximately \[ 984{,}064 \times 2304 \;\approx \; 2.27 \times 10^9 \mbox{ MACs}. \]

- 2.

- Bottleneck: 1x1 Then 3x3. First use a 1x1 convolution to reduce the

input from 256 channels down to 64, apply the 3x3 on these 64 channels,

and then restore 256 channels if needed.

- 1x1 stage (256 \(\to \) 64): \((256 \times 64)\) weights plus 64 biases \(\Rightarrow \sim 16{,}448\) parameters. The output is \((64 \times 64 \times 64)\) (i.e. \(64\) channels, each \(64\times 64\)). This step requires \(\sim 64 \times 64\) spatial positions \(\times (256 \times 64)\) MACs \(\approx 67\times 10^6\) MACs.

- 3x3 stage (64 \(\to \) 256): \((64 \times 256 \times 3 \times 3) + 256\) parameters \(\approx 147{,}712\). The final output shape is \((256 \times 62 \times 62)\). Each of the \(984{,}064\) positions requires \((64 \times 3 \times 3)=576\) MACs, totaling \(\sim 567\times 10^6\) MACs.

- Totals for 1x1 + 3x3: \[ \mbox{Params} = 16{,}384 + 64 + 147{,}456 + 256 \;=\;164{,}160, \qquad \mbox{MACs} \approx 67\times 10^6 + 567\times 10^6 = 634\times 10^6. \]

- Parameters: Direct 3x3 uses \(\sim 590{,}080\) parameters versus \(\sim 164{,}160\) in the bottleneck approach—a 3.6\(\times \) reduction.

- FLOPs: Direct 3x3 costs \(\sim 2.27\times 10^9\) MACs vs. \(\sim 0.63\times 10^9\) for the 1x1+3x3 route—again around a 3.6\(\times \) speedup.

Although the bottleneck adds an extra layer (the 1x1 convolution), the combined memory footprint and compute overhead are significantly lower. This allows CNNs to grow deeper—by reducing intermediate channels—without exploding in parameter or FLOP requirements.

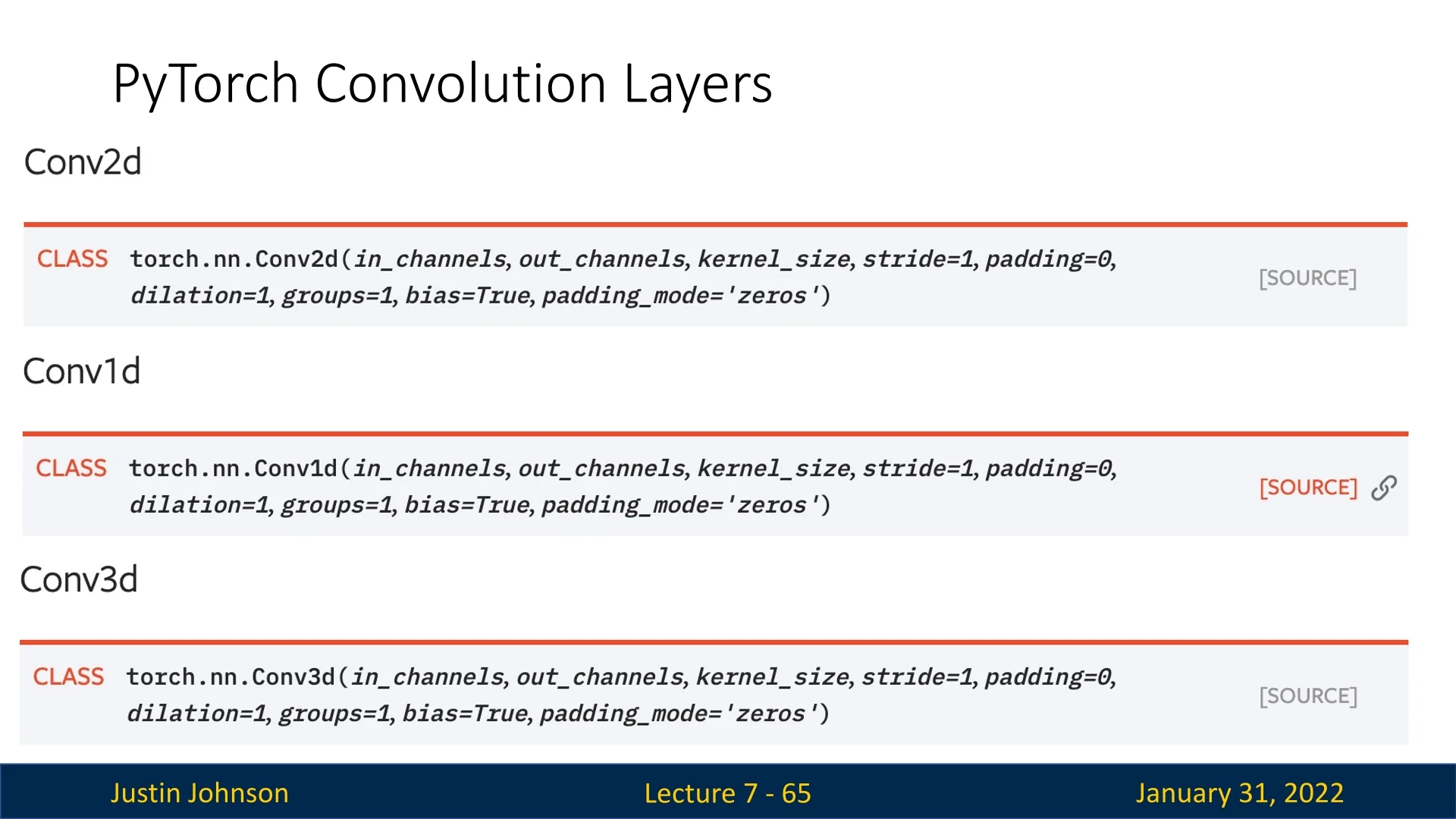

7.8.2 1D Convolutions

1D convolutions operate on sequential data where input dimensions are \( C_{\mbox{in}} \times W \). Filters have shape \( C_{\mbox{out}} \times C_{\mbox{in}} \times K \), where \( K \) is the kernel size.

Numerical Example: 1D Convolution on Multichannel Time Series Data Consider an accelerometer dataset collected from a wearable device, where each row represents acceleration along the \( x, y, z \) axes over time. The input sequence is:

\[ X = \begin {bmatrix} 2 & 3 & 1 & 0 & 4 \\ 1 & 2 & 0 & 1 & 3 \\ 0 & 1 & 2 & 3 & 1 \end {bmatrix} \] with dimensions \( 3 \times 5 \) (three input channels, five time steps).

We apply a 1D convolution with:

- A filter of size \( K = 3 \) operating across all input channels.

- Kernel weights: \[ W = \begin {bmatrix} 1 & 0 & -1 \\ -1 & 1 & 0 \\ 0 & -1 & 1 \end {bmatrix} \]

- Zero padding \( P = 0 \).

- Stride \( S = 2 \).

Computing the Output The output size is computed as: \[ W' = \frac {(W - K + 2P)}{S} + 1 = \frac {(5 - 3 + 2 \times 0)}{2} + 1 = \frac {2}{2} + 1 = 1 + 1 = 2. \]

Since the numerator \( (W - K + 2P) = 2 \) is divisible by \( S = 2 \), no flooring is needed. Thus, the final output has shape \( 1 \times 2 \).

Now, computing the convolution while skipping every second step due to \( S=2 \):

1. First step (\( Y_1 \)): Apply the kernel to the first three columns of the input (columns 1-3): \[ Y_1 = (1 \cdot 2) + (0 \cdot 3) + (-1 \cdot 1) + (-1 \cdot 1) + (1 \cdot 2) + (0 \cdot 0) + (0 \cdot 0) + (-1 \cdot 1) + (1 \cdot 2) \] \[ = 2 + 0 - 1 - 1 + 2 + 0 + 0 - 1 + 2 = 3. \]

2. Second step (\( Y_2 \)): Move by \( S=2 \) steps, selecting columns 3-5: \[ Y_2 = (1 \cdot 1) + (0 \cdot 0) + (-1 \cdot 4) + (-1 \cdot 0) + (1 \cdot 1) + (0 \cdot 3) + (0 \cdot 2) + (-1 \cdot 3) + (1 \cdot 1) \] \[ = 1 + 0 - 4 - 0 + 1 + 0 + 0 - 3 + 1 = -4. \]

Thus, the final output is: \[ Y = [3, -4] \] with shape \( 1 \times 2 \).

Applications of 1D Convolutions

- Activity Recognition: Used on accelerometer data to classify human activity (e.g., standing, walking, running).

- Audio Processing: Applied to waveforms for sound classification or speech recognition.

- Financial Time Series: Detects trends and patterns in stock prices or sensor signals.

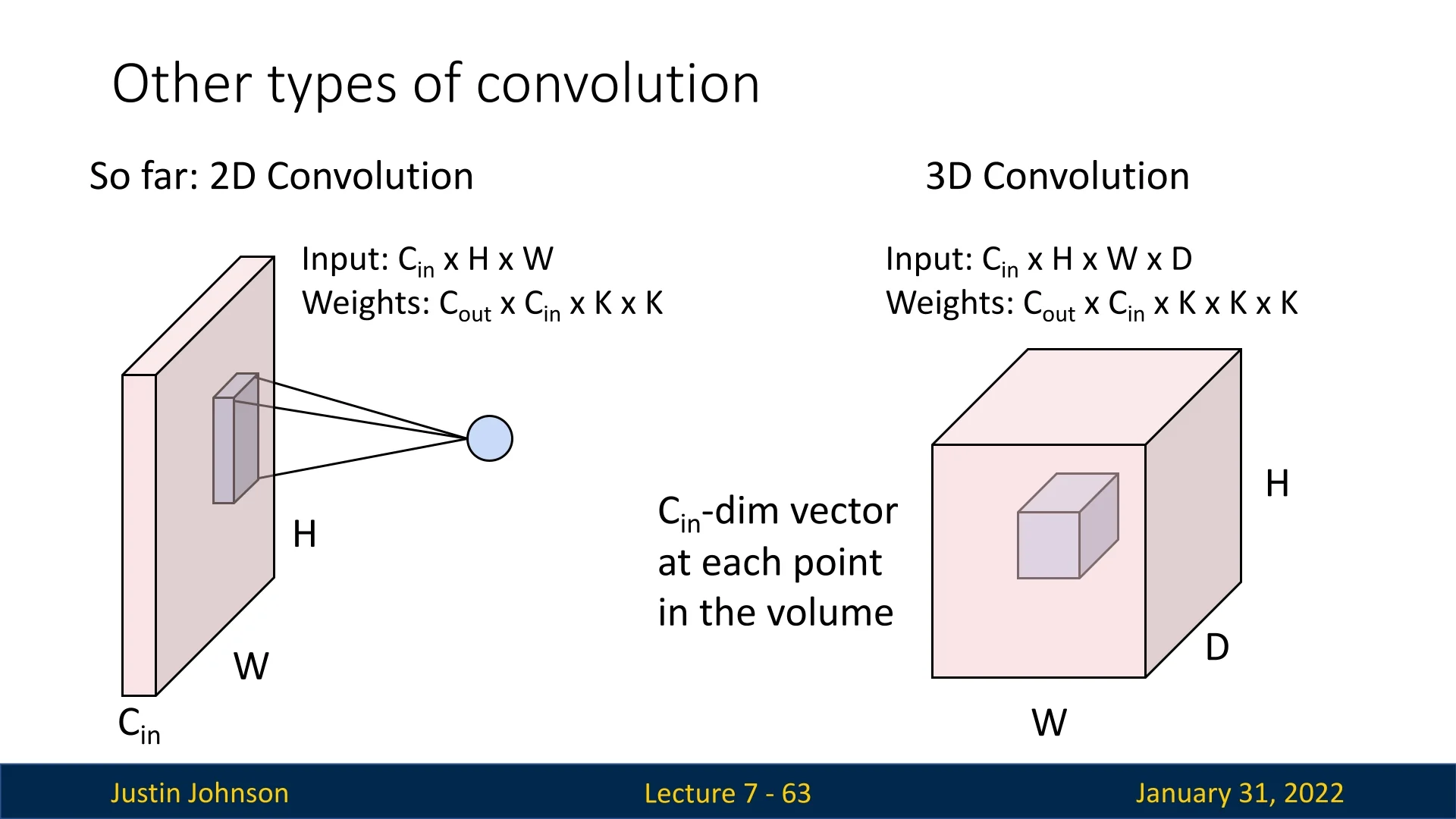

7.8.3 3D Convolutions

3D convolutions extend 2D convolutions to volumetric data, where input dimensions are \( C_{\mbox{in}} \times H \times W \times D \). Filters have shape \( C_{\mbox{out}} \times C_{\mbox{in}} \times K \times K \times K \).

Numerical Example: 3D Convolution on Volumetric Data Consider a volumetric input (e.g., a single-channel medical scan or short video clip) represented as a 5D tensor: \[ X \in \mathbb {R}^{(N,\, C_{\mbox{in}},\, D_{\mbox{in}},\, H_{\mbox{in}},\, W_{\mbox{in}})} = (1,\, 1,\, 4,\, 4,\, 4), \] where \(N=1\) is the batch size, \(C_{\mbox{in}}=1\) is the number of input channels, and \(D_{\mbox{in}}, H_{\mbox{in}}, W_{\mbox{in}}\) are the spatial depth, height, and width.

We apply a 3D convolution with the following parameters:

- Kernel size \(K = (3,3,3)\).

- Zero padding \(P = 0\).

- Stride \(S = 1\).

- Output channels \(C_{\mbox{out}} = 1\).

Output Size Calculation The output spatial dimensions are given by: \[ O = \left \lfloor \frac {I - K + 2P}{S} \right \rfloor + 1. \] Substituting our values: \[ D_{\mbox{out}} = H_{\mbox{out}} = W_{\mbox{out}} = \left \lfloor \frac {4 - 3 + 0}{1} \right \rfloor + 1 = 2. \] Hence the output tensor has shape: \[ Y \in \mathbb {R}^{(N,\, C_{\mbox{out}},\, D_{\mbox{out}},\, H_{\mbox{out}},\, W_{\mbox{out}})} = (1,\, 1,\, 2,\, 2,\, 2). \]

Input Tensor (Depth Slices) \[ X = \begin {bmatrix} \begin {bmatrix} 1 & -2 & 5 & 2 \\ -1 & 1 & 4 & -3 \\ 1 & 5 & 5 & 2 \\ -1 & -2 & 2 & 2 \end {bmatrix}, \begin {bmatrix} -3 & 0 & -1 & -4 \\ 2 & 0 & -4 & -1 \\ -5 & 4 & 0 & 3 \\ -5 & 5 & 5 & 4 \end {bmatrix}, \begin {bmatrix} -3 & 1 & -2 & 3 \\ -3 & -1 & -3 & 1 \\ -1 & 3 & 1 & -4 \\ -2 & 3 & -4 & 4 \end {bmatrix}, \begin {bmatrix} 3 & 4 & -1 & -4 \\ -2 & 1 & 2 & -3 \\ -5 & -2 & -4 & 2 \\ -2 & -4 & 0 & 0 \end {bmatrix} \end {bmatrix}. \]

Filter Tensor (Kernel) For \(C_{\mbox{out}} = 1\) and \(C_{\mbox{in}} = 1\), the kernel has full shape \[ K \in \mathbb {R}^{(1,\,1,\,3,\,3,\,3)}. \] We can visualize the 3D kernel (depth slices) as: \[ K = \begin {bmatrix} \begin {bmatrix} -2 & 0 & 2 \\ 1 & 3 & -2 \\ -2 & 0 & -2 \end {bmatrix}, \begin {bmatrix} -2 & 2 & 0 \\ 2 & 3 & 3 \\ 2 & 3 & 0 \end {bmatrix}, \begin {bmatrix} -3 & 2 & 1 \\ 1 & -2 & 3 \\ 1 & -2 & -3 \end {bmatrix} \end {bmatrix}. \]

Role of the Input Channel Dimension \(C_{\mbox{in}}\) In this example, \(C_{\mbox{in}}=1\), meaning the convolution integrates purely over spatial dimensions (depth, height, width). In general, for multi-channel inputs such as an RGB video (\(C_{\mbox{in}}=3\)) or multi-modal medical volume (\(C_{\mbox{in}}>1\)), the kernel expands accordingly: \[ K \in \mathbb {R}^{(C_{\mbox{out}},\, C_{\mbox{in}},\, K_D,\, K_H,\, K_W)}. \] At each output position, the convolution sums over all input channels: \[ Y_{c_{\mbox{out}}, d, h, w} = \sum _{c_{\mbox{in}}=0}^{C_{\mbox{in}}-1} \sum _{i=0}^{K_D-1} \sum _{j=0}^{K_H-1} \sum _{k=0}^{K_W-1} X_{c_{\mbox{in}},\, d+i,\, h+j,\, w+k} \, K_{c_{\mbox{out}},\, c_{\mbox{in}},\, i,\, j,\, k}. \] This mechanism fuses cross-channel information—critical, for example, in learning color-motion correlations in video or multi-spectral cues in MRI.

Single-Channel Case (\(C_{\mbox{in}}=C_{\mbox{out}}=1\)) For our numerical example, the channel sum reduces to a single term: \[ Y(d, h, w) = \sum _{i=0}^{2} \sum _{j=0}^{2} \sum _{k=0}^{2} X(d+i, h+j, w+k) \cdot K(i,j,k). \]

Step-by-Step Computation Each output element is the dot product of a \(3\times 3\times 3\) subvolume of \(X\) with the kernel \(K\).

- First output value \(Y(0,0,0)\): \begin {align*} Y(0,0,0) &= \sum _{i=0}^{2}\sum _{j=0}^{2}\sum _{k=0}^{2} X(i,j,k)\,K(i,j,k) \\ &= (-10) + (0) + (-11) = \mathbf {-21}. \end {align*}

- Second value \(Y(0,0,1)\): (shifted one step in width) \[ Y(0,0,1) = \sum _{i,j,k} X(i,j,k+1)\,K(i,j,k) = \mathbf {21}. \]

Final Output Tensor Repeating this process for all valid spatial positions yields: \[ Y = \begin {bmatrix} \begin {bmatrix} -21 & 21 \\ 13 & 28 \end {bmatrix}, \begin {bmatrix} 32 & -61 \\ 17 & -29 \end {bmatrix} \end {bmatrix}. \] Thus the final output tensor has dimensions \(2 \times 2 \times 2\) (or equivalently \(1 \times 1 \times 2 \times 2 \times 2\) including batch and channel).

Applications of 3D Convolutions

- Video Processing: Learns spatio-temporal patterns across consecutive frames.

- Medical Imaging: Processes volumetric data such as CT or MRI scans.

- 3D Object Understanding: Operates directly on voxelized or point-cloud representations.

- Preserve and jointly model spatial and temporal dependencies.

- Enable direct learning of motion-aware or volumetric features, without requiring stacked 2D convolutions.

- High Computational Cost: Complexity grows with \(C_{\mbox{in}}\times C_{\mbox{out}}\) and 3D kernel volume.

- Limited Long-Range Modeling: Capture short-term temporal or local spatial context but often require hierarchical architectures for long-range dependencies.

7.8.4 Efficient Convolutions for Mobile and Embedded Systems

Deep learning models, particularly convolutional neural networks (CNNs), are computationally expensive, requiring extensive multiply-add (MAC) operations [307]. Traditional convolutions, while effective, become infeasible for real-time applications on edge devices such as mobile phones, IoT devices, and embedded systems due to high memory and computational costs [547, 600]. To address these limitations, efficient alternatives such as spatial separable convolutions and depthwise separable convolutions have been introduced. These techniques power lightweight architectures like MobileNet [229], ShuffleNet [780], and EfficientNet [600].

7.8.5 Spatial Separable Convolutions

Concept and Intuition Spatial separable convolutions focus on reducing the computational complexity of convolution operations by factorizing a standard 2D convolution into two separate operations—one along the width and another along the height of the kernel. Instead of using a single \( K \times K \) kernel, spatial separable convolution decomposes it into two kernels: \( K \times 1 \) followed by \( 1 \times K \).

For example, consider a standard \( 3 \times 3 \) convolution kernel applied to an \( H \times W \) input image. The output dimensions for a stride of 1 and no padding are computed as:

\[ (H - K + 1) \times (W - K + 1). \]

Using spatial separable convolutions, we first apply a \( K \times 1 \) convolution, reducing only the height dimension:

\[ (H - K + 1) \times W. \]

We then apply a \( 1 \times K \) convolution on the intermediate output, reducing the width dimension:

\[ (H - K + 1) \times (W - K + 1). \]

Thus, the final output shape remains identical to that of a conventional \( K \times K \) convolution while significantly reducing the number of multiplications.

To illustrate this process, consider the transformation of a \( 3 \times 3 \) matrix:

\[ \begin {bmatrix} 3 & 6 & 9 \\ 4 & 8 & 12 \\ 5 & 10 & 15 \end {bmatrix} = \begin {bmatrix} 3 \\ 4 \\ 5 \end {bmatrix} \times \begin {bmatrix} 1 & 2 & 3 \end {bmatrix}. \]

Here, the \( 3 \times 3 \) matrix is first decomposed into a \( 3 \times 1 \) vector, producing an intermediate output of shape \( 3 \times 1 \). The second convolution then extends it back to a \( 3 \times 3 \) shape, preserving the feature representation while reducing computational cost.

Limitations and Transition to Depthwise Separable Convolutions Although spatial separable convolutions significantly reduce computations, they are not widely used in deep learning architectures for feature extraction. This is because not all convolution kernels can be factorized in this manner [316]. During training, the network is constrained to use only separable kernels, limiting the representational power of the model.

A common example of a spatially separable kernel used in traditional computer vision is the Sobel filter, which is employed for edge detection. However, in deep learning applications, a more general and effective form of separable convolution, known as depthwise separable convolution, has gained widespread adoption. Unlike spatial separable convolutions, depthwise separable convolutions do not impose constraints on the kernel’s factorability, making them more practical for efficient deep learning models.

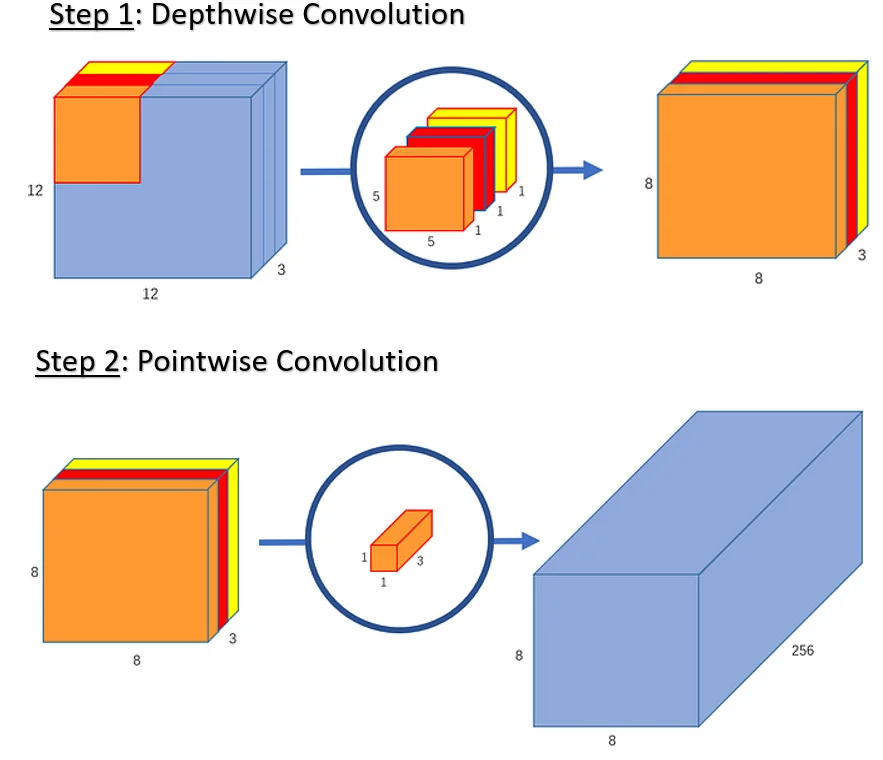

7.8.6 Depthwise Separable Convolutions

Concept and Motivation Depthwise separable convolutions factorize a standard convolution into two simpler steps, greatly reducing parameters and computation while often preserving most of the representational power. A standard \(K \times K\) convolution kernel of shape \[ C_{\mathrm {out}} \times C_{\mathrm {in}} \times K \times K \] tries to do two jobs at once:

- 1.

- Learn spatial patterns inside each channel.

- 2.

- Learn cross-channel interactions between different input channels.

Depthwise separable convolutions separate these roles:

- 1.

- Depthwise (Spatial) Convolution: A \(K \times K\) filter is applied independently to each input channel. For an input feature map of shape \((H \times W \times C_{\mathrm {in}})\), this produces an intermediate feature map of shape \((H \times W \times C_{\mathrm {in}})\). At this stage, each channel learns its own spatial features (e.g., per-channel edge or texture detectors); there is no mixing between channels.

- 2.

- Pointwise (\(1 \times 1\)) Convolution: A bank of \(1 \times 1\) filters then performs a learned linear combination across the \(C_{\mathrm {in}}\) channels at each spatial location. This step mixes information across channels and adjusts the channel dimension from \(C_{\mathrm {in}}\) to \(C_{\mathrm {out}}\), producing an output of shape \((H \times W \times C_{\mathrm {out}})\).

This two-stage “depthwise + pointwise” design is also called channel-wise spatial convolution. Unlike spatially factorized kernels (such as \(3 \times 3\) decomposed into \(1 \times 3\) and \(3 \times 1\)), depthwise separable convolutions do not impose a low-rank constraint on the full kernel, making them easy to insert into existing architectures such as Inception, VGG, or ResNet [104, 229].

Computational and Parameter Efficiency We now compare the computational cost (MACs) and parameter count of a standard \(K \times K\) convolution with its depthwise separable counterpart. For clarity, we consider a single feature map (no batch dimension) of shape \[ (H \times W \times C_{\mathrm {in}}) \quad \longrightarrow \quad (H \times W \times C_{\mathrm {out}}) \] with stride \(1\) and “same” padding, so that the spatial resolution \(H \times W\) stays the same.

Standard \((K \times K)\) Convolution A standard convolution uses \(C_{\mathrm {out}}\) kernels, each of shape \((K \times K \times C_{\mathrm {in}})\). Thus:

- Parameters: \[ \mbox{Params}_{\mbox{std}} = K^2 \, C_{\mathrm {in}} \, C_{\mathrm {out}}. \]

- Multiply-Adds (MACs): There are \(H W C_{\mathrm {out}}\) output elements, each computed as a dot product over \(K^2 C_{\mathrm {in}}\) weights. Therefore: \[ \mbox{MACs}_{\mbox{std}} = (H W C_{\mathrm {out}}) \times (K^2 C_{\mathrm {in}}) = H W K^2 C_{\mathrm {in}} C_{\mathrm {out}}. \]

Depthwise Separable Convolution Depthwise separable convolution decomposes this into:

-

Depthwise Convolution (Spatial Only): We apply one \(K \times K\) filter per input channel, so there are \(C_{\mathrm {in}}\) filters in total. Each filter has shape \((K \times K)\), and each channel is processed independently: \begin {align*} \text {Params}_{\text {depthwise}} &= K^2 \, C_{\mathrm {in}}, \\ \text {MACs}_{\text {depthwise}} &= (H W C_{\mathrm {in}}) \times K^2 = H W K^2 C_{\mathrm {in}}. \end {align*}

The output has shape \((H \times W \times C_{\mathrm {in}})\).

- Pointwise (\(1 \times 1\)) Convolution (Channel Mixing): Next, we apply \(1 \times 1\) filters to mix channels and reach \(C_{\mathrm {out}}\) output channels. Each \(1 \times 1\) kernel has shape \((C_{\mathrm {in}})\), and there are \(C_{\mathrm {out}}\) such kernels: \begin {align*} \text {Params}_{\text {pointwise}} &= C_{\mathrm {in}} \, C_{\mathrm {out}}, \\ \text {MACs}_{\text {pointwise}} &= (H W C_{\mathrm {out}}) \times C_{\mathrm {in}} = H W C_{\mathrm {in}} C_{\mathrm {out}}. \end {align*}

Summing both stages: \begin {align*} \text {Params}_{\text {DSConv}} &= K^2 C_{\mathrm {in}} + C_{\mathrm {in}} C_{\mathrm {out}} = C_{\mathrm {in}} \bigl (K^2 + C_{\mathrm {out}}\bigr ), \\ \text {MACs}_{\text {DSConv}} &= H W K^2 C_{\mathrm {in}} + H W C_{\mathrm {in}} C_{\mathrm {out}} = H W C_{\mathrm {in}} \bigl (K^2 + C_{\mathrm {out}}\bigr ). \end {align*}

Cost Reduction Ratio The reduction in cost when switching from a standard convolution to a depthwise separable convolution is: \[ \frac {\mbox{MACs}_{\mbox{std}}}{\mbox{MACs}_{\mbox{DSConv}}} = \frac {H W K^2 C_{\mathrm {in}} C_{\mathrm {out}}}{H W C_{\mathrm {in}} (K^2 + C_{\mathrm {out}})} = \frac {K^2 C_{\mathrm {out}}}{K^2 + C_{\mathrm {out}}}. \] The same ratio holds for parameter counts. In typical CNNs, \(C_{\mathrm {out}} \gg K^2\) (for example, \(C_{\mathrm {out}} = 256\) and \(K^2 = 9\) for a \(3\times 3\) kernel). In that regime, \[ \frac {K^2 C_{\mathrm {out}}}{K^2 + C_{\mathrm {out}}} \approx K^2, \] so a \(3 \times 3\) depthwise separable convolution is roughly \(9\times \) more efficient than a standard \(3 \times 3\) convolution in both parameters and MACs.

Summary of Costs For convenience, we summarize parameter and MAC counts:

\[ \begin {array}{l|c|c} \textbf {Layer Type} & \textbf {Parameters} & \textbf {MACs} \\ \hline \mbox{Standard } (K \times K) & K^2 C_{\mathrm {in}} C_{\mathrm {out}} & H W K^2 C_{\mathrm {in}} C_{\mathrm {out}} \\[3pt] \mbox{Depthwise} & K^2 C_{\mathrm {in}} & H W K^2 C_{\mathrm {in}} \\[3pt] \mbox{Pointwise } (1 \times 1) & C_{\mathrm {in}} C_{\mathrm {out}} & H W C_{\mathrm {in}} C_{\mathrm {out}} \\[3pt] \mbox{Depthwise Separable (total)} & C_{\mathrm {in}}(K^2 + C_{\mathrm {out}}) & H W C_{\mathrm {in}}(K^2 + C_{\mathrm {out}}) \end {array} \]

Example: \((K=3,\;C_{\mathrm {in}}=128,\;C_{\mathrm {out}}=256,\;H=W=32)\)

Consider an input feature map of shape \((32 \times 32 \times 128)\) and a desired output of shape \((32 \times 32 \times 256)\), using a \(3 \times 3\) kernel, stride \(1\), and “same” padding.

-

Standard Convolution: \begin {align*} \text {Params}_{\text {std}} &= K^2 C_{\mathrm {in}} C_{\mathrm {out}} = 3^2 \cdot 128 \cdot 256 = 294{,}912, \\ \text {MACs}_{\text {std}} &= H W K^2 C_{\mathrm {in}} C_{\mathrm {out}} = 32 \cdot 32 \cdot 9 \cdot 128 \cdot 256 \\ &= 301{,}989{,}888 \approx 3.02 \times 10^8 \text { MACs}. \end {align*}

-

Depthwise Separable Convolution:

- Depthwise step: \begin {align*} \text {Params}_{\text {depthwise}} &= K^2 C_{\mathrm {in}} = 3^2 \cdot 128 = 1{,}152, \\ \text {MACs}_{\text {depthwise}} &= H W K^2 C_{\mathrm {in}} = 32 \cdot 32 \cdot 9 \cdot 128 \\ &= 1{,}179{,}648 \approx 1.18 \times 10^6. \end {align*}

- Pointwise step: \begin {align*} \text {Params}_{\text {pointwise}} &= C_{\mathrm {in}} C_{\mathrm {out}} = 128 \cdot 256 = 32{,}768, \\ \text {MACs}_{\text {pointwise}} &= H W C_{\mathrm {in}} C_{\mathrm {out}} = 32 \cdot 32 \cdot 128 \cdot 256 \\ &= 33{,}554{,}432 \approx 3.36 \times 10^7. \end {align*}

Total depthwise separable cost: \begin {align*} \text {Params}_{\text {DSConv}} &= 1{,}152 + 32{,}768 = 33{,}920, \\ \text {MACs}_{\text {DSConv}} &= 1{,}179{,}648 + 33{,}554{,}432 = 34{,}734{,}080 \approx 3.47 \times 10^7. \end {align*}

Comparing the two: \[ \frac {\mbox{Params}_{\mbox{std}}}{\mbox{Params}_{\mbox{DSConv}}} = \frac {294{,}912}{33{,}920} \approx 8.69, \qquad \frac {\mbox{MACs}_{\mbox{std}}}{\mbox{MACs}_{\mbox{DSConv}}} = \frac {301{,}989{,}888}{34{,}734{,}080} \approx 8.69. \] Thus, in this realistic setting, replacing a standard \(3 \times 3\) convolution with a depthwise separable convolution reduces both parameters and computation by almost an order of magnitude, while still allowing the network to first learn rich spatial filters per channel and then flexibly mix them across channels in the pointwise step.

Reduction Factor By separating spatial and channel mixing, depthwise separable convolutions can reduce computational cost by up to an order of magnitude in many practical scenarios, enabling advanced CNNs to run on mobile or embedded devices with minimal resource usage.

A common approximate reduction ratio is: \[ \frac {\mbox{Cost}_\mbox{DSConv}}{\mbox{Cost}_\mbox{StdConv}} \;\approx \; \frac {C_{\mbox{in}} \times K^2 + C_{\mbox{in}} \times C_{\mbox{out}}}{C_{\mbox{in}} \times C_{\mbox{out}} \times K^2} \;=\; \frac {1}{C_{\mbox{out}}} + \frac {1}{K^2}. \] As an example, for \(K=3\) and \(C_{\mbox{out}}=256\), the ratio is \(\frac {1}{256} + \frac {1}{9} \approx 0.11\), i.e. about a \(\sim 9\times \) reduction in FLOPs compared to a standard \(3\times 3\) convolution.

- MobileNet [229]: Relies on depthwise separable layers to achieve low-latency inference on mobile devices.

- ShuffleNet [780]: Combines depthwise separable convs with a channel shuffle operation to further improve efficiency.

- Xception [104]: Extends Inception-like modules by fully replacing standard convolutions with depthwise separable variants for all spatial operations.

- EfficientNet [600]: Integrates depthwise separable layers in a compound scaling framework, balancing network width, depth, and resolution.

- Reduced Cross-Channel Expressiveness: A standard convolution captures both spatial patterns and cross-channel correlations in a single operation: each \(K \times K\) filter integrates information from all \(C_{\mathrm {in}}\) channels over its receptive field before the nonlinearity, enabling rich, intertwined feature interactions. Depthwise separable convolutions factorize this process. The depthwise stage applies spatial filters independently to each channel (no inter-channel mixing), and the subsequent pointwise \(1 \times 1\) stage performs only linear combinations across channels at fixed spatial positions. Although stacking several depthwise separable blocks still allows complex dependencies to emerge (pointwise mixing in one block feeds into depthwise spatial filtering in the next), this sequential mechanism is less expressive per layer than a monolithic standard convolution. Interactions that one standard layer can model directly may require multiple depthwise separable layers to approximate, potentially making optimization harder and slightly reducing representational power. To compensate, modern architectures often incorporate explicit cross-channel modeling modules such as Squeeze-and-Excitation (SE) blocks or attention mechanisms, which adaptively reweight channels and restore some of the lost flexibility [234, 104].

- Substantial Compute Savings: By decoupling spatial filtering \(\bigl (O(K^2 C_{\mathrm {in}})\bigr )\) from channel mixing \(\bigl (O(C_{\mathrm {in}} C_{\mathrm {out}})\bigr )\), depthwise separable convolutions reduce MACs and parameters by factors of roughly \(K^2\) for typical settings (e.g., \(\sim 8\mbox{--}9\times \) for \(K=3\), large \(C_{\mathrm {out}}\)), as shown in the previous cost analysis. This dramatic efficiency gain is crucial for real-time inference on resource-constrained devices such as smartphones, embedded boards, or edge accelerators, often with only a modest drop in accuracy.

Overall, depthwise separable convolutions have become a cornerstone of efficient CNN design, trading a small amount of per-layer expressiveness for large reductions in computation and parameter count, and thereby enabling high-performing models in mobile and embedded environments.

7.8.7 Summary of Specialized Convolutions

- 1x1 convolutions: Used for feature selection, dimensionality reduction, and efficient computation.

- 1D convolutions: Applied in sequential data processing, such as text and audio.

- 3D convolutions: Extend feature extraction to volumetric and spatiotemporal data.

- Spatial separable convolutions: Factorize standard convolutions into separate width and height operations, reducing computation while maintaining output dimensions. Unfortunately, these convolutions are not common as only special filters can be spatially separated, which makes this type of convolutions impractical for deep learning purposes.

- Depthwise separable convolutions: Split convolutions into depthwise and pointwise operations, significantly reducing computational cost while preserving some feature extraction capabilities, making it useful in efficient/mobile architectures where speed is a critical factor.

These specialized convolutions enhance the flexibility and efficiency of neural networks, enabling them to process diverse types of structured data, over different computation platforms (from expensive and powerful GPU servers up to common mobile devices).

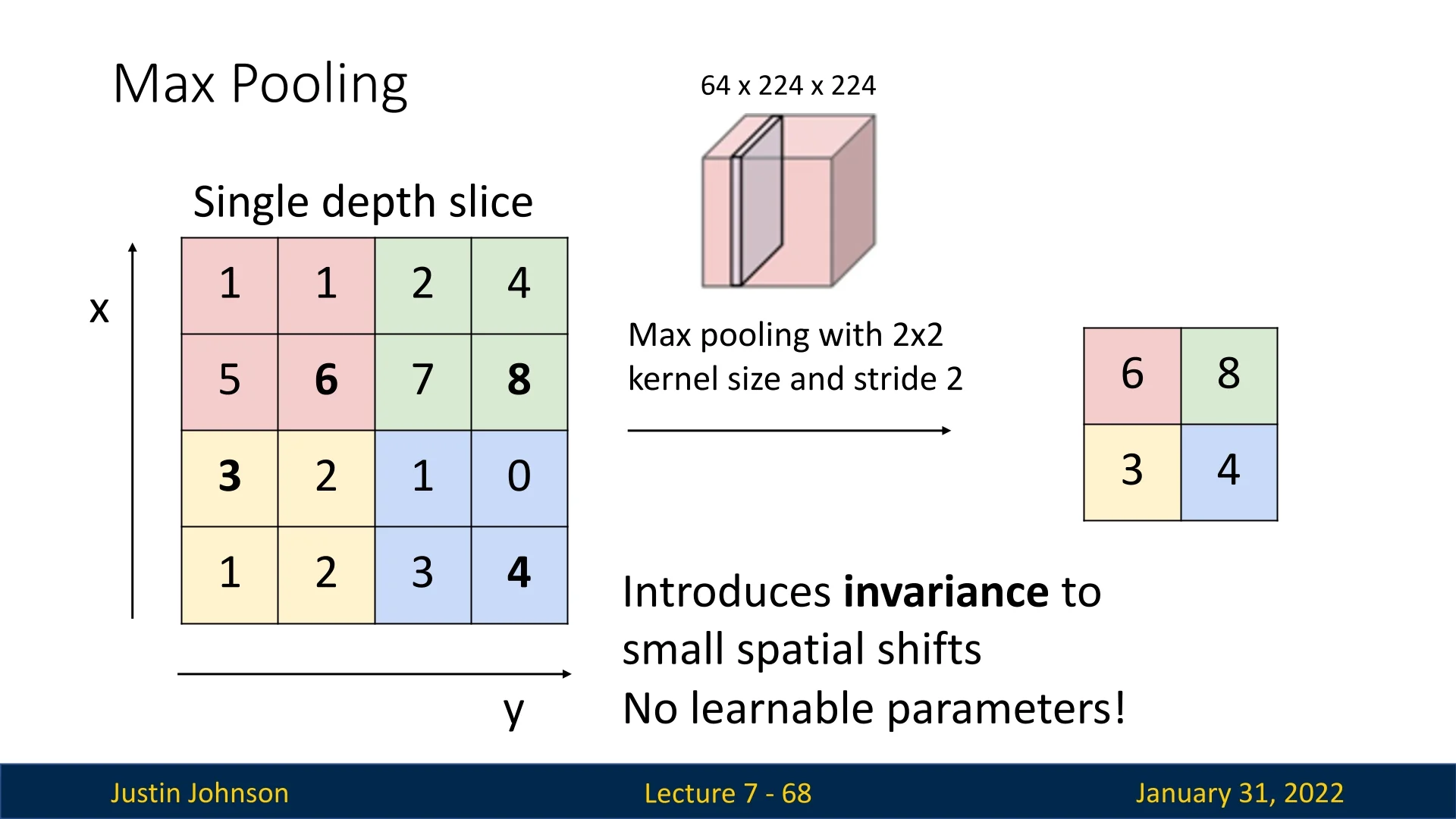

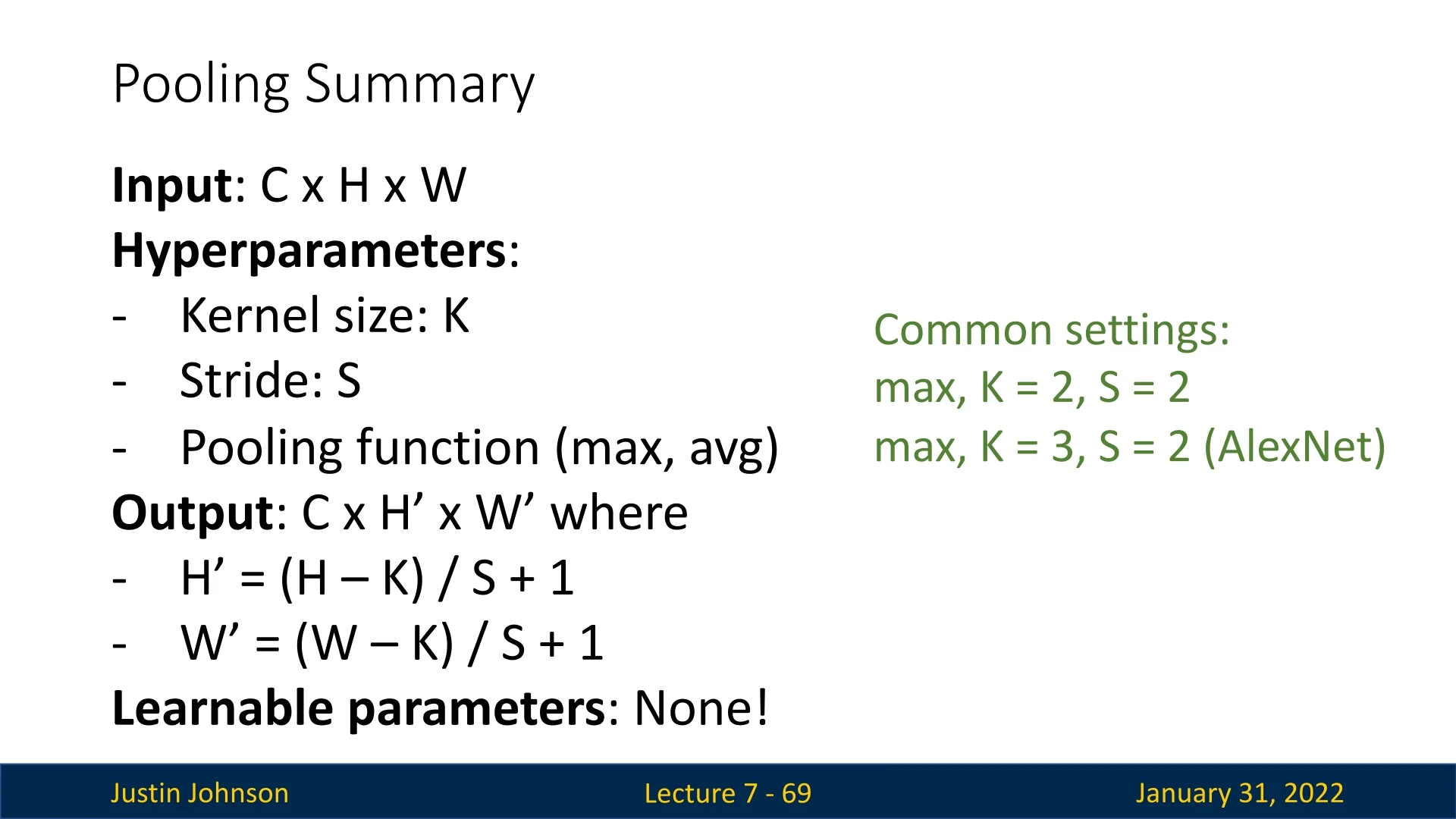

7.11 Pooling Layers

Pooling layers are a key component of convolutional neural networks (CNNs), serving to condense spatial information and highlight the most salient features of an input. Unlike convolutional layers, which learn filters, pooling layers have no learnable parameters; they instead apply a fixed aggregation function (such as maximum or average) over local neighborhoods. Hyperparameters such as the kernel size, stride, and pooling type control the degree of downsampling. This simple yet powerful mechanism reduces feature map resolution, lowers computational cost, increases robustness to spatial variations, and expands the effective receptive field in deeper layers.

7.9.1 Types of Pooling

Pooling operates much like a convolution: a window slides across the feature map according to the stride, and a function is applied within each region to produce one representative value. When the stride equals the kernel size, the pooling regions are non-overlapping.

- Max Pooling: Selects the maximum activation within each window, retaining the strongest response and emphasizing dominant local features.

- Average Pooling: Computes the average value within each window, creating a smoother, more generalized representation of the feature map. However, excessive averaging can blur fine details or weaken distinctive local patterns.

7.9.2 Effect and Benefits of Pooling

Pooling summarizes local activations to form a more compact and abstract feature representation. By keeping only the strongest or average responses in each region, the network becomes more efficient and more robust. The main benefits include:

- Reduced Computation and Memory: Pooling decreases the spatial resolution of feature maps, lowering the number of activations passed to deeper layers. This directly reduces both computational load and memory requirements.

- Translation Invariance: Pooling introduces robustness to small translations or distortions in the input. A feature that shifts slightly within its receptive field is still captured after pooling, making the network less sensitive to exact spatial alignment.

- Improved Generalization: By discarding minor local variations, pooling acts as a form of regularization, reducing the risk of overfitting to fine-grained details or noise present in the training data.

- Expanded Receptive Field: Since pooling reduces the resolution of intermediate representations, subsequent convolutional layers operate over proportionally larger portions of the original input. This allows deeper layers to integrate global spatial context and capture more abstract patterns.

In summary, pooling layers help CNNs focus on the most informative spatial cues while controlling computational complexity and promoting invariance—key ingredients for robust hierarchical feature learning.

Enrichment 7.11.3: Pooling Layers in Backpropagation

Pooling layers are commonly used in convolutional neural networks (CNNs) to reduce spatial dimensions while retaining important features. The two most common types are max pooling and average pooling. Understanding how backpropagation works for these layers is important, since it determines how error signals are routed back to earlier feature maps.

Forward Pass of Pooling Layers

Pooling operates on small regions (e.g., a \(2 \times 2\) window) and reduces each region to a single value, downsampling the feature map without introducing learnable parameters:

- Max pooling: Selects the maximum value from the window, emphasizing dominant activations.

- Average pooling: Computes the average of all values in the window, yielding a smoothed summary.

Example of Forward Pass Consider a single \(4 \times 4\) input matrix \(X\); we will use the same \(X\) for both the forward and backward pass examples:

\[ X = \begin {bmatrix} 1 & 3 & 2 & 1 \\ \mathbf {4} & 2 & 1 & \mathbf {5} \\ 2 & 0 & \mathbf {3} & 1 \\ 1 & \mathbf {5} & 2 & 2 \end {bmatrix} \]

We apply a \(2 \times 2\) pooling window with stride 2, giving four non-overlapping regions (quadrants).

Max pooling computes: \[ Y_{\mbox{max}} = \begin {bmatrix} \max (1,3,\mathbf {4},2) & \max (2,1,1,\mathbf {5}) \\[4pt] \max (2,0,1,\mathbf {5}) & \max (\mathbf {3},1,2,2) \end {bmatrix} = \begin {bmatrix} 4 & 5 \\ 5 & 3 \end {bmatrix}. \] The max positions in \(X\) are: \[ (1,0),\ (1,3),\ (3,1),\ (2,2). \]

Average pooling computes: \[ Y_{\mbox{avg}} = \begin {bmatrix} \frac {1+3+4+2}{4} & \frac {2+1+1+5}{4} \\[4pt] \frac {2+0+1+5}{4} & \frac {3+1+2+2}{4} \end {bmatrix} = \begin {bmatrix} 2.5 & 2.25 \\ 2 & 2 \end {bmatrix}. \]

Backpropagation Through Pooling Layers

During backpropagation, we propagate gradients from the pooled outputs back to the inputs. Let the upstream gradient with respect to the pooled output be \[ \frac {\partial L}{\partial Y} = \begin {bmatrix} 0.2 & -0.3 \\ 0.4 & 0.1 \end {bmatrix}, \] where \(L\) is the loss. We now see how this gradient is mapped back to \(\frac {\partial L}{\partial X}\).

Max Pooling Backpropagation For max pooling, the gradient from each pooled value is passed back only to the input element that was the maximum in that window; all other elements in the window receive zero gradient. This makes max pooling behave like a “routing” operation for gradients.

Using the max locations from the forward pass:

- The gradient \(0.2\) (from the top-left pooled output) is assigned to \(X_{1,0}\).

- The gradient \(-0.3\) (top-right) is assigned to \(X_{1,3}\).

- The gradient \(0.4\) (bottom-left) is assigned to \(X_{3,1}\).

- The gradient \(0.1\) (bottom-right) is assigned to \(X_{2,2}\).

Thus the downstream gradient with respect to \(X\) is: \[ \frac {\partial L}{\partial X} = \begin {bmatrix} 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ \mathbf {0.2} & 0 & 0 & \mathbf {-0.3} \\ 0 & 0 & \mathbf {0.1} & 0 \\ 0 & \mathbf {0.4} & 0 & 0 \end {bmatrix}. \]

- Sparse gradients: Only the max positions in each window receive nonzero gradients, while all other activations are ignored in backpropagation. This sparsity can slow learning, since fewer units contribute to the parameter updates.

- Reduced feedback to fine details: Because non-max activations receive no gradient, small but potentially informative responses may not be reinforced, which can matter in tasks that require precise spatial detail.

To alleviate excessive sparsity, modern architectures sometimes use overlapping pooling (stride smaller than window size) or replace pooling entirely with strided convolutions, which maintain dense gradient flow through learnable filters.

Average Pooling Backpropagation For average pooling, the gradient from each pooled output is distributed evenly among all elements in its window. If a window contains \(n\) elements, each input in that window receives \(\frac {1}{n}\) of the upstream gradient.

In our example, each \(2 \times 2\) window has \(n=4\) elements, so we divide each entry of \(\frac {\partial L}{\partial Y}\) by 4:

- Top-left window: \(0.2 / 4 = 0.05\).

- Top-right window: \(-0.3 / 4 = -0.075\).

- Bottom-left window: \(0.4 / 4 = 0.1\).

- Bottom-right window: \(0.1 / 4 = 0.025\).

The resulting gradient with respect to \(X\) is dense: \[ \frac {\partial L}{\partial X} = \begin {bmatrix} 0.05 & 0.05 & -0.075 & -0.075 \\ 0.05 & 0.05 & -0.075 & -0.075 \\ 0.1 & 0.1 & 0.025 & 0.025 \\ 0.1 & 0.1 & 0.025 & 0.025 \end {bmatrix}. \]

General Backpropagation Rules for Pooling

For a pooling window with inputs \(\{x_i\}_{i=1}^n\), pooled output \(O\), and upstream gradient \(\frac {\partial L}{\partial O}\), the local gradients are:

- Max pooling: Let \(x_{\max }\) be the input that attained the maximum in the forward pass. Then \[ \frac {\partial L}{\partial x_i} = \begin {cases} \frac {\partial L}{\partial O} & \mbox{if } x_i = x_{\max }, \\ 0 & \mbox{otherwise}. \end {cases} \]

- Average pooling: All inputs share the gradient equally: \[ \frac {\partial L}{\partial x_i} = \frac {1}{n}\,\frac {\partial L}{\partial O} \quad \mbox{for all } i = 1,\dots ,n. \]

These rules emphasize the conceptual difference between max and average pooling in backpropagation: max pooling routes gradients through a few dominant activations, whereas average pooling spreads gradients more uniformly across all inputs in each region.

7.9.3 Global Pooling Layers

Global pooling layers apply a pooling operation over the entire spatial dimension of a feature map, unlike regular pooling (e.g., \(2\times 2\)) which operates on smaller local regions. By collapsing each feature map into a single value, these layers often replace fully connected (FC) layers at the end of convolutional networks, drastically reducing parameter counts.

General Advantages

- More Robustness to Overfitting: Global pooling removes the need for large FC layers. It doesn’t introduce additional learnable weights, and merely aggregates existing activations. Hence, using it significantly cuts the number of trainable parameters.

- Lightweight Alternative to FC Layers: Rather than flattening high-dimensional feature maps, introducing several MLP layers at the end of the CNN, a single value per map suffices, increasing computation speed while decreasing the size of the model.

- Improved Generalization: Summarizing or selecting the strongest feature responses promotes focusing on essential aspects of the learned representation.

Global Average Pooling (GAP)

Operation GAP computes the mean of all activations in a feature map \(X\in \mathbb {R}^{H\times W}\): \[ O = \frac {1}{HW}\sum _{i=1}^{H}\sum _{j=1}^{W} X_{ij}. \] This is performed independently for each channel.

- Direct Channel-to-Feature Mapping: Each channel in the input shrinks to a single numeric representation, facilitating interpretability.